https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escitalopram

Escitalopram, sold under the brand names Cipralex and Lexapro among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. Escitalopram is mainly used to treat major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. It is taken by mouth.

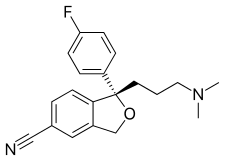

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, nausea, sexual problems, and feeling tired. More serious side effects may include suicide in people under the age of 25. It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe. Escitalopram is the (S)-stereoisomer of the earlier medication citalopram, hence the name escitalopram.

Escitalopram was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002. In the United States the wholesale cost is about $2.04 per month as of 2017. In the United Kingdom, as of 2018, non-proprietary escitalopram is around 1 / 20th as costly as the proprietary version. Escitalopram is sometimes replaced by twice the dose of citalopram. In 2016 it was the 26th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 25 million prescriptions.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cipralex, Lexapro, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603005 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% |

| Protein binding | ~56% |

| Metabolism | Liver, specifically the enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 |

| Elimination half-life | 27–32 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.244.188 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

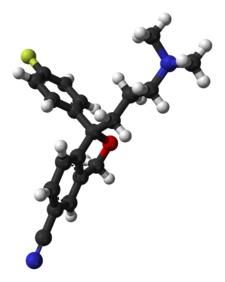

| Formula | C20H21FN2O |

| Molar mass | 324.392 g/mol (414.43 as oxalate) g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

Escitalopram, sold under the brand names Cipralex and Lexapro among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. Escitalopram is mainly used to treat major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. It is taken by mouth.

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, nausea, sexual problems, and feeling tired. More serious side effects may include suicide in people under the age of 25. It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe. Escitalopram is the (S)-stereoisomer of the earlier medication citalopram, hence the name escitalopram.

Escitalopram was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002. In the United States the wholesale cost is about $2.04 per month as of 2017. In the United Kingdom, as of 2018, non-proprietary escitalopram is around 1 / 20th as costly as the proprietary version. Escitalopram is sometimes replaced by twice the dose of citalopram. In 2016 it was the 26th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 25 million prescriptions.

Medical uses

Escitalopram has FDA approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and adults, and generalized anxiety disorder in adults. In European countries and Australia, it is approved for depression (MDD) and anxiety disorders, these include: general anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.

Depression

Escitalopram

was approved by regulatory authorities for the treatment of major

depressive disorder on the basis of four placebo controlled, double-blind trials, three of which demonstrated a statistical superiority over placebo.

Controversy existed regarding the effectiveness of escitalopram

compared with its predecessor, citalopram. The importance of this issue

followed from the greater cost of escitalopram relative to the generic

mixture of isomers of citalopram, prior to the expiration of the

escitalopram patent in 2012, which led to charges of evergreening. Accordingly, this issue has been examined in at least 10 different systematic reviews and meta analyses. As of 2012,

reviews had concluded (with caveats in some cases) that escitalopram is

modestly superior to citalopram in efficacy and tolerability.

A 2011 review concluded that second-generation antidepressants

appear equally effective, although they may differ in onset and side

effects.

Treatment guidelines issued by the National Institute of Health and

Clinical Excellence and by the American Psychiatric Association

generally reflect this viewpoint.

In 2018, a systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing

the efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs showed

escitalopram to be one of the most effective.

Anxiety disorder

Escitalopram

appears to be effective in treating general anxiety disorder, with

relapse on escitalopram at 20% rather than placebo at 50%.

Escitalopram appears effective in treating social anxiety disorder.

Other

Escitalopram, as well as other SSRIs, is effective in reducing the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, whether taken in the luteal phase only or continuously. There are no good data available for escitalopram as treatment for seasonal affective disorder as of 2011. SSRIs do not appear to be useful for preventing tension headaches or migraines.

Side effects

Escitalopram, like other SSRIs, has been shown to affect sexual functions causing side effects such as decreased libido, delayed ejaculation, and anorgasmia.

An analysis conducted by the FDA found a statistically

insignificant 1.5 to 2.4-fold (depending on the statistical technique

used) increase of suicidality among the adults treated with escitalopram for psychiatric indications.

The authors of a related study note the general problem with

statistical approaches: due to the rarity of suicidal events in clinical

trials, it is hard to draw firm conclusions with a sample smaller than

two million patients.

Escitalopram is not associated with weight gain. For example,

0.6 kg mean weight change after 6 months of treatment with escitalopram

for depression was insignificant and similar to that with placebo

(0.2 kg).

Citalopram and escitalopram are associated with dose-dependent QT interval prolongation and should not be used in those with congenital long QT syndrome or known pre-existing QT interval prolongation, or in combination with other medicines that prolong the QT interval. ECG measurements should be considered for patients with cardiac disease, and electrolyte disturbances

should be corrected before starting treatment. In December 2011, the UK

implemented new restrictions on the maximum daily doses at 20 mg for

adults and 10 mg for those older than 65 years or with liver impairment. There are concerns of higher rates of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes compared with other SSRIs.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada did not

similarly order restrictions on escitalopram dosage, only on its

predecessor citalopram.

Discontinuation symptoms

Escitalopram discontinuation, particularly abruptly, may cause certain withdrawal symptoms such as "electric shock" sensations (also known as "brain shivers" or "brain zaps"), dizziness, acute depressions and irritability, as well as heightened senses of akathisia.

Sexual dysfunction

Some people experience persistent sexual side effects after they stop taking SSRIs. This is known as post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD). Common symptoms include genital anesthesia, erectile dysfunction, anhedonia,

decreased libido, premature ejaculation, vaginal lubrication issues,

and nipple insensitivity in women. Rates are unknown, and there is no

established treatment.

Pregnancy

Antidepressant

exposure (including escitalopram) is associated with shorter duration

of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by

55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0 .4="" a="" abortion.="" advantages="" an="" antidepressant="" associated="" association="" baby.="" during="" effects="" exposure="" heart="" in="" increased="" is="" may="" negative="" not="" of="" on="" outweigh="" p="" points="" possible="" pregnancy="" problems="" risk="" spontaneous="" ssri="" tentative="" the="" their="" there="" thus="" use="" with="">

Overdose

Excessive doses of escitalopram usually cause relatively minor untoward effects, such as agitation and tachycardia. However, dyskinesia, hypertonia, and clonus

may occur in some cases. Therapeutic blood levels of escitalopram are

usually in the range of 20–80 μg/L but may reach 80–200 μg/L in the

elderly, patients with hepatic dysfunction, those who are poor CYP2C19

metabolizers or following acute overdose. Monitoring of the drug in plasma or serum is generally accomplished using chromatographic methods. Chiral techniques are available to distinguish escitalopram from its racemate, citalopram. Escitalopram seems to be less dangerous than citalopram in overdose and comparable to other SSRIs.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Escitalopram increases intrasynaptic levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin by blocking the reuptake of the neurotransmitter into the presynaptic neuron. Of the SSRIs currently available, escitalopram has the highest selectivity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) compared to the norepinephrine transporter (NET), making the side-effect profile relatively mild in comparison to less-selective SSRIs.

Escitalopram is a substrate of P-glycoprotein and hence P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as verapamil and quinidine may improve its blood brain barrier penetrability.

In a preclinical study in rats combining escitalopram with a

P-glycoprotein inhibitor, its antidepressant-like effects were enhanced.

Interactions

Escitalopram, similarly to other SSRIs, inhibits CYP2D6 and hence may increase plasma levels of a number of CYP2D6 substrates such as aripiprazole, risperidone, tramadol, codeine, etc. As escitalopram is only a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6, analgesia from tramadol may not be affected. Escitalopram should be taken with caution when using St. John's wort. Exposure to escitalopram is increased moderately, by about 50%, when it is taken with omeprazole. The authors of this study suggested that this increase is unlikely to be of clinical concern. Caution should be used when taking cough medicine containing dextromethorphan (DXM) as serotonin syndrome has been reported.

Bupropion has been found to significantly increase citalopram plasma concentration and systemic exposure; as of April 2018 the interaction with escitalopram had not been studied, but some monographs warned of the potential interaction.

Escitalopram can also prolong the QT interval and hence it is not

recommended in patients that are concurrently on other medications that

also have the ability to prolong the QT interval. These drugs include antiarrhythmics, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, some antihistamines (astemizole, mizolastine) and some antiretrovirals (ritonavir, saquinavir, lopinavir). Being a SSRI, escitalopram should not be given concurrently with MAOIs or other serotonergic medications.

History

Cipralex brand escitalopram 10mg package and tablet sheet

Escitalopram was developed in close cooperation between Lundbeck and Forest Laboratories.

Its development was initiated in the summer of 1997, and the resulting

new drug application was submitted to the U.S. FDA in March 2001. The

short time (3.5 years) it took to develop escitalopram can be attributed

to the previous extensive experience of Lundbeck and Forest with citalopram, which has similar pharmacology.

The FDA issued the approval of escitalopram for major depression

in August 2002 and for generalized anxiety disorder in December 2003. On

May 23, 2006, the FDA approved a generic version of escitalopram by Teva. On July 14 of that year, however, the U.S. District Court of Delaware decided in favor of Lundbeck regarding the patent infringement dispute and ruled the patent on escitalopram valid.

In 2006, Forest Laboratories was granted an 828-day (2 years and 3 months) extension on its US patent for escitalopram.

This pushed the patent expiration date from December 7, 2009 to

September 14, 2011. Together with the 6-month pediatric exclusivity, the

final expiration date was March 14, 2012.

Society and culture

Allegations of illegal marketing

In

2004, two separate civil suits alleging illegal marketing of citalopram

and escitalopram for use by children and teenagers by Forest were

initiated by two whistleblowers, one by a practicing physician named

Joseph Piacentile, and the other by a Forest salesman named Christopher

Gobble.

In February 2009, these two suits received support from the US Attorney

for Massachusetts and were combined into one. Eleven states and the

District of Columbia have also filed notices of intention to intervene

as plaintiffs in the action. The suits allege that Forest illegally

engaged in off-label promoting of Lexapro for use in children, that the

company hid the results of a study showing lack of effectiveness in

children, and that the company paid kickbacks

to physicians to induce them to prescribe Lexapro to children. It was

also alleged that the company conducted so-called "seeding studies"

that were, in reality, marketing efforts to promote the drug's use by

doctors.

Forest responded to these allegations that it "is committed to adhering

to the highest ethical and legal standards, and off-label promotion and

improper payments to medical providers have consistently been against

Forest policy."

In 2010 Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., agreed to pay more than $313

million to settle the charges over Lexapro and two other drugs,

Levothroid and Celexa.

Brand names

Escitalopram is sold under many brand names worldwide such as Cipralex and Lexapro.