| Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gastro, stomach bug, stomach virus, stomach flu, gastric flu, gastrointestinitis |

| |

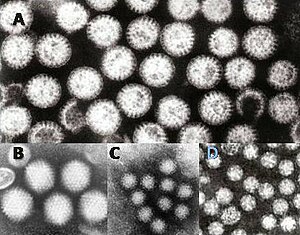

| Gastroenteritis viruses: A = rotavirus, B = adenovirus, C = norovirus and D = astrovirus. The virus particles are shown at the same magnification to allow size comparison. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever |

| Complications | Dehydration |

| Causes | Viruses, bacteria, parasites, fungus |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, occasionally stool culture |

| Differential diagnosis | Inflammatory bowel disease, malabsorption syndrome, lactose intolerance |

| Prevention | Hand washing, drinking clean water, proper disposal of human waste, breastfeeding |

| Treatment | Oral rehydration solution (combination of water, salts, and sugar), intravenous fluids |

| Frequency | 2.4 billion (2015) |

| Deaths | 1.3 million (2015) |

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract—the stomach and small intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of energy and dehydration may also occur. This typically lasts less than two weeks. It is not related to influenza, though it has erroneously been called the "stomach flu".

Gastroenteritis is usually caused by viruses. However, bacteria, parasites, and fungus can also cause gastroenteritis. In children, rotavirus is the most common cause of severe disease. In adults, norovirus and Campylobacter are common causes. Eating improperly prepared food, drinking contaminated water or close contact with a person who is infected can spread the disease. Treatment is generally the same with or without a definitive diagnosis, so testing to confirm is usually not needed.

Prevention includes hand washing with soap, drinking clean water, proper disposal of human waste and breastfeeding babies instead of using formula. The rotavirus vaccine is recommended as a prevention for children. Treatment involves getting enough fluids. For mild or moderate cases, this can typically be achieved by drinking oral rehydration solution (a combination of water, salts and sugar). In those who are breastfed, continued breastfeeding is recommended. For more severe cases, intravenous fluids may be needed. Fluids may also be given by a nasogastric tube. Zinc supplementation is recommended in children. Antibiotics are generally not needed. However, antibiotics are recommended for young children with a fever and bloody diarrhea.

In 2015, there were two billion cases of gastroenteritis, resulting in 1.3 million deaths globally. Children and those in the developing world are affected the most. In 2011, there were about 1.7 billion cases, resulting in about 700,000 deaths of children under the age of five. In the developing world, children less than two years of age frequently get six or more infections a year. It is less common in adults, partly due to the development of immunity.

Signs and symptoms

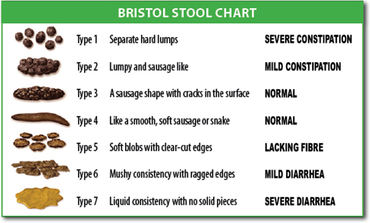

Gastroenteritis usually involves both diarrhea and vomiting. Sometimes, only one or the other is present. This may be accompanied by abdominal cramps. Signs and symptoms usually begin 12–72 hours after contracting the infectious agent. If due to a virus, the condition usually resolves within one week. Some viral infections also involve fever, fatigue, headache and muscle pain. If the stool is bloody, the cause is less likely to be viral and more likely to be bacterial. Some bacterial infections cause severe abdominal pain and may persist for several weeks.

Children infected with rotavirus usually make a full recovery within three to eight days. However, in poor countries treatment for severe infections is often out of reach and persistent diarrhea is common. Dehydration is a common complication of diarrhea. Severe dehydration in children may be recognized if the skin color and position returns slowly when pressed. This is called "prolonged capillary refill" and "poor skin turgor". Abnormal breathing is another sign of severe dehydration. Repeat infections are typically seen in areas with poor sanitation, and malnutrition. Stunted growth and long-term cognitive delays can result.

Reactive arthritis occurs in 1% of people following infections with Campylobacter species. Guillain–Barré syndrome occurs in 0.1%. Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) may occur due to infection with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli or Shigella species. HUS causes low platelet counts, poor kidney function, and low red blood cell count (due to their breakdown). Children are more predisposed to getting HUS than adults. Some viral infections may produce benign infantile seizures.

Cause

Viruses (particularly rotavirus) and the bacteria Escherichia coli and Campylobacter species are the primary causes of gastroenteritis. There are, however, many other infectious agents that can cause this syndrome including parasites and fungus. Non-infectious causes are seen on occasion, but they are less likely than a viral or bacterial cause. Risk of infection is higher in children due to their lack of immunity. Children are also at higher risk because they are less likely to practice good hygiene habits. Children living in areas without easy access to water and soap are especially vulnerable.

Viral

Rotavirus, norovirus, adenovirus, and astrovirus are known to cause viral gastroenteritis. Rotavirus is the most common cause of gastroenteritis in children, and produces similar rates in both the developed and developing world. Viruses cause about 70% of episodes of infectious diarrhea in the pediatric age group. Rotavirus is a less common cause in adults due to acquired immunity. Norovirus is the cause in about 18% of all cases.

Norovirus is the leading cause of gastroenteritis among adults in America, causing greater than 90% of outbreaks. These localized epidemics typically occur when groups of people spend time in close physical proximity to each other, such as on cruise ships, in hospitals, or in restaurants. People may remain infectious even after their diarrhea has ended. Norovirus is the cause of about 10% of cases in children.

Bacterial

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (ATCC 14028) as seen with a microscope at 1000 fold magnification and following Gram staining.

In the developed world Campylobacter jejuni is the primary cause of bacterial gastroenteritis, with half of these cases associated with exposure to poultry. In children, bacteria are the cause in about 15% of cases, with the most common types being Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter species.

If food becomes contaminated with bacteria and remains at room

temperature for a period of several hours, the bacteria multiply and

increase the risk of infection in those who consume the food.

Some foods commonly associated with illness include raw or undercooked

meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs; raw sprouts; unpasteurized milk and

soft cheeses; and fruit and vegetable juices. In the developing world, especially sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, cholera is a common cause of gastroenteritis. This infection is usually transmitted by contaminated water or food.

Toxigenic Clostridium difficile is an important cause of diarrhea that occurs more often in the elderly. Infants can carry these bacteria without developing symptoms. It is a common cause of diarrhea in those who are hospitalized and is frequently associated with antibiotic use. Staphylococcus aureus infectious diarrhea may also occur in those who have used antibiotics. Acute "traveler's diarrhea" is usually a type of bacterial gastroenteritis, while the persistent form is usually parasitic.

Acid-suppressing medication appears to increase the risk of significant

infection after exposure to a number of organisms, including Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, and Campylobacter species. The risk is greater in those taking proton pump inhibitors than with H2 antagonists.

Parasitic

A number of parasites can cause gastroenteritis. Giardia lamblia is most common, but Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium spp., and other species have also been implicated. As a group, these agents comprise about 10% of cases in children. Giardia occurs more commonly in the developing world, but this type of illness can occur nearly everywhere. It occurs more commonly in persons who have traveled to areas with high prevalence, children who attend day care, men who have sex with men, and following disasters.

Transmission

Transmission may occur from drinking contaminated water or when people share personal objects. Water quality typically worsens during the rainy season and outbreaks are more common at this time. In areas with four seasons, infections are more common in the winter. Worldwide, bottle-feeding of babies with improperly sanitized bottles is a significant cause. Transmission rates are also related to poor hygiene, (especially among children), in crowded households, and in those with poor nutritional status. Adults who have developed immunities might still carry certain organisms without exhibiting symptoms. Thus, adults can become natural reservoirs of certain diseases. While some agents (such as Shigella) only occur in primates, others (such as Giardia) may occur in a wide variety of animals.

Non-infectious

There are a number of non-infectious causes of inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Some of the more common include medications (like NSAIDs), certain foods such as lactose (in those who are intolerant), and gluten (in those with celiac disease). Crohn's disease is also a non-infectious source of (often severe) gastroenteritis. Disease secondary to toxins may also occur. Some food-related conditions associated with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea include: ciguatera poisoning due to consumption of contaminated predatory fish, scombroid associated with the consumption of certain types of spoiled fish, tetrodotoxin poisoning from the consumption of puffer fish among others, and botulism typically due to improperly preserved food.

In the United States, rates of emergency department use for

noninfectious gastroenteritis dropped 30% from 2006 until 2011. Of the

twenty most common conditions seen in the emergency department, rates of

noninfectious gastroenteritis had the largest decrease in visits in

that time period.

Pathophysiology

Gastroenteritis caused due to intestinal infection.

Gastroenteritis is defined as vomiting or diarrhea due to inflammation of the small or large bowel, often due to infection. The changes in the small bowel are typically noninflammatory, while the ones in the large bowel are inflammatory. The number of pathogens required to cause an infection varies from as few as one (for Cryptosporidium) to as many as 108 (for Vibrio cholerae).

Diagnosis

Gastroenteritis is typically diagnosed clinically, based on a person's signs and symptoms. Determining the exact cause is usually not needed as it does not alter management of the condition.

However, stool cultures should be performed in those with blood in the stool, those who might have been exposed to food poisoning, and those who have recently traveled to the developing world. It may also be appropriate in children younger than 5, old people, and those with poor immune function. Diagnostic testing may also be done for surveillance. As hypoglycemia occurs in approximately 10% of infants and young children, measuring serum glucose in this population is recommended. Electrolytes and kidney function should also be checked when there is a concern about severe dehydration.

Dehydration

A determination of whether or not the person has dehydration

is an important part of the assessment, with dehydration typically

divided into mild (3–5%), moderate (6–9%), and severe (≥10%) cases. In children, the most accurate signs of moderate or severe dehydration are a prolonged capillary refill, poor skin turgor, and abnormal breathing. Other useful findings (when used in combination) include sunken eyes, decreased activity, a lack of tears, and a dry mouth. A normal urinary output and oral fluid intake is reassuring. Laboratory testing is of little clinical benefit in determining the degree of dehydration. Thus the use of urine testing or ultrasounds is generally not needed.

Differential diagnosis

Other potential causes of signs and symptoms that mimic those seen in gastroenteritis that need to be ruled out include appendicitis, volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease, urinary tract infections, and diabetes mellitus. Pancreatic insufficiency, short bowel syndrome, Whipple's disease, coeliac disease, and laxative abuse should also be considered. The differential diagnosis can be complicated somewhat if the person exhibits only vomiting or diarrhea (rather than both).

Appendicitis may present with vomiting, abdominal pain, and a small amount of diarrhea in up to 33% of cases. This is in contrast to the large amount of diarrhea that is typical of gastroenteritis. Infections of the lungs or urinary tract in children may also cause vomiting or diarrhea. Classical diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) presents with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, but without diarrhea. One study found that 17% of children with DKA were initially diagnosed as having gastroenteritis.

Prevention

Percentage of rotavirus tests with positive results, by surveillance week, United States, July 2000 – June 2009.

Lifestyle

A supply of easily accessible uncontaminated water and good sanitation practices are important for reducing rates of infection and clinically significant gastroenteritis. Personal measures (such as hand washing with soap) have been found to decrease rates of gastroenteritis in both the developing and developed world by as much as 30%. Alcohol-based gels may also be effective. Food or drink that is thought to be contaminated should be avoided.

Breastfeeding is important, especially in places with poor hygiene, as is improvement of hygiene generally. Breast milk reduces both the frequency of infections and their duration.

Vaccination

Due to both its effectiveness and safety, in 2009 the World Health Organization recommended that the rotavirus vaccine be offered to all children globally. Two commercial rotavirus vaccines exist and several more are in development. In Africa and Asia these vaccines reduced severe disease among infants and countries that have put in place national immunization programs have seen a decline in the rates and severity of disease. This vaccine may also prevent illness in non-vaccinated children by reducing the number of circulating infections.

Since 2000, the implementation of a rotavirus vaccination program in

the United States has substantially decreased the number of cases of

diarrhea by as much as 80 percent. The first dose of vaccine should be given to infants between 6 and 15 weeks of age. The oral cholera vaccine has been found to be 50–60% effective over 2 years.

Management

Gastroenteritis is usually an acute and self-limiting disease that does not require medication. The preferred treatment in those with mild to moderate dehydration is oral rehydration therapy (ORT). For children at risk of dehydration from vomiting, taking a single dose of the anti vomiting medication metoclopramide or ondansetron, may be helpful, and butylscopolamine is useful in treating abdominal pain.

Rehydration

The primary treatment of gastroenteritis in both children and adults is rehydration. This is preferably achieved by drinking rehydration solution, although intravenous delivery may be required if there is a decreased level of consciousness or if dehydration is severe.

Drinking replacement therapy products made with complex carbohydrates

(i.e. those made from wheat or rice) may be superior to those based on

simple sugars. Drinks especially high in simple sugars, such as soft drinks and fruit juices, are not recommended in children under 5 years of age as they may increase diarrhea. Plain water may be used if more specific ORT preparations are unavailable or the person is not willing to drink them. A nasogastric tube can be used in young children to administer fluids if warranted. In those who require intravenous fluids, one to four hours' worth is often sufficient.

Dietary

It is recommended that breast-fed infants continue to be nursed in

the usual fashion, and that formula-fed infants continue their formula

immediately after rehydration with ORT. Lactose-free or lactose-reduced formulas usually are not necessary. Children should continue their usual diet during episodes of diarrhea with the exception that foods high in simple sugars should be avoided. The BRAT diet

(bananas, rice, applesauce, toast and tea) is no longer recommended, as

it contains insufficient nutrients and has no benefit over normal

feeding.

Some probiotics have been shown to be beneficial in reducing both the duration of illness and the frequency of stools. They may also be useful in preventing and treating antibiotic associated diarrhea. Fermented milk products (such as yogurt) are similarly beneficial. Zinc supplementation appears to be effective in both treating and preventing diarrhea among children in the developing world.

Antiemetics

Antiemetic medications may be helpful for treating vomiting in children. Ondansetron

has some utility, with a single dose being associated with less need

for intravenous fluids, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased vomiting. Metoclopramide might also be helpful. However, the use of ondansetron might possibly be linked to an increased rate of return to hospital in children. The intravenous preparation of ondansetron may be given orally if clinical judgment warrants. Dimenhydrinate, while reducing vomiting, does not appear to have a significant clinical benefit.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not usually used for gastroenteritis, although they

are sometimes recommended if symptoms are particularly severe or if a susceptible bacterial cause is isolated or suspected. If antibiotics are to be employed, a macrolide (such as azithromycin) is preferred over a fluoroquinolone due to higher rates of resistance to the latter. Pseudomembranous colitis, usually caused by antibiotic use, is managed by discontinuing the causative agent and treating it with either metronidazole or vancomycin. Bacteria and protozoans that are amenable to treatment include Shigella Salmonella typhi, and Giardia species. In those with Giardia species or Entamoeba histolytica, tinidazole treatment is recommended and superior to metronidazole. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of antibiotics in young children who have both bloody diarrhea and fever.

Antimotility agents

Antimotility medication has a theoretical risk of causing

complications, and although clinical experience has shown this to be

unlikely, these drugs are discouraged in people with bloody diarrhea or diarrhea that is complicated by fever. Loperamide, an opioid analogue, is commonly used for the symptomatic treatment of diarrhea. Loperamide is not recommended in children, however, as it may cross the immature blood–brain barrier and cause toxicity. Bismuth subsalicylate, an insoluble complex of trivalent bismuth and salicylate, can be used in mild to moderate cases, but salicylate toxicity is theoretically possible.

Epidemiology

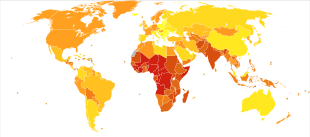

Deaths due to diarrhoeal diseases per million persons in 2012

0–2

3–10

11–18

19–30

31–46

47–80

81–221

222–450

451–606

607–1799

Disability-adjusted life year for diarrhea per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.

|

no data

≤less 500

500–1000

1000–1500

1500–2000

2000–2500

2500–3000

|

3000–3500

3500–4000

4000–4500

4500–5000

5000–6000

≥6000

|

It is estimated that there were two billion cases of gastroenteritis that resulted in 1.3 million deaths globally in 2015. Children and those in the developing world are most commonly affected.[15] As of 2011, in those less than five, there were about 1.7 billion cases resulting in 0.7 million deaths,[16] with most of these occurring in the world's poorest nations. More than 450,000 of these fatalities are due to rotavirus in children under 5 years of age. Cholera causes about three to five million cases of disease and kills approximately 100,000 people yearly.

In the developing world, children less than two years of age frequently

get six or more infections a year that result in significant

gastroenteritis. It is less common in adults, partly due to the development of acquired immunity.

In 1980, gastroenteritis from all causes caused 4.6 million

deaths in children, with the majority occurring in the developing world.

Death rates were reduced significantly (to approximately 1.5 million

deaths annually) by the year 2000, largely due to the introduction and

widespread use of oral rehydration therapy. In the US, infections causing gastroenteritis are the second most common infection (after the common cold), and they result in between 200 and 375 million cases of acute diarrhea and approximately ten thousand deaths annually, with 150 to 300 of these deaths in children less than five years of age.

History

The first usage of "gastroenteritis" was in 1825. Before this time it was commonly known as typhoid fever

or "cholera morbus", among others, or less specifically as "griping of

the guts", "surfeit", "flux", "colic", "bowel complaint", or any one of a

number of other archaic names for acute diarrhea. Cholera morbus is a historical term that was used to refer to gastroenteritis rather than specifically cholera.

Society and culture

Gastroenteritis is associated with many colloquial names, including "Montezuma's revenge", "Delhi belly", "la turista", and "back door sprint", among others. It has played a role in many military campaigns and is believed to be the origin of the term "no guts no glory".

Gastroenteritis is the main reason for 3.7 million visits to physicians a year in the United States and 3 million visits in France. In the United States gastroenteritis as a whole is believed to result in costs of US$23 billion per year with that due to rotavirus alone resulting in estimated costs of US$1 billion a year.

Research

There are a number of vaccines against gastroenteritis in development. For example, vaccines against Shigella and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) are two of the leading bacterial causes of gastroenteritis worldwide.

Other animals

Many of the same agents cause gastroenteritis in cats and dogs as in humans. The most common organisms are Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, and Salmonella. A large number of toxic plants may also cause symptoms.

Some agents are more specific to a certain species. Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) occurs in pigs resulting in vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration. It is believed to be introduced to pigs by wild birds and there is no specific treatment available. It is not transmissible to humans.