Omega−3 fatty acids, also called Omega-3 oils, ω−3 fatty acids or n−3 fatty acids, are polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFAs) characterized by the presence of a double bond three atoms away

from the terminal methyl group in their chemical structure. They are

widely distributed in nature, being important constituents of animal lipid metabolism, and they play an important role in the human diet and in human physiology. The three types of omega−3 fatty acids involved in human physiology are α-linolenic acid (ALA), found in plant oils, and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), both commonly found in marine oils. Marine algae and phytoplankton are primary sources of omega−3 fatty acids. Common sources of plant oils containing ALA include walnut, edible seeds, clary sage seed oil, algal oil, flaxseed oil, Sacha Inchi oil, Echium oil, and hemp oil, while sources of animal omega−3 fatty acids EPA and DHA include fish, fish oils, eggs from chickens fed EPA and DHA, squid oils, krill oil, and certain algae.

Mammals are unable to synthesize the essential omega−3 fatty acid ALA and can only obtain it through diet. However, they can use ALA, when available, to form EPA and DHA, by creating additional double bonds along its carbon chain (desaturation) and extending it (elongation). Namely, ALA (18 carbons and 3 double bonds) is used to make EPA (20 carbons and 5 double bonds), which is then used to make DHA (22 carbons and 6 double bonds). The ability to make the longer-chain omega−3 fatty acids from ALA may be impaired in aging. In foods exposed to air, unsaturated fatty acids are vulnerable to oxidation and rancidity. Dietary supplementation with omega−3 fatty acids does not appear to affect the risk of death, cancer or heart disease. Furthermore, fish oil supplement studies have failed to support claims of preventing heart attacks or strokes or any vascular disease outcomes.

Mammals are unable to synthesize the essential omega−3 fatty acid ALA and can only obtain it through diet. However, they can use ALA, when available, to form EPA and DHA, by creating additional double bonds along its carbon chain (desaturation) and extending it (elongation). Namely, ALA (18 carbons and 3 double bonds) is used to make EPA (20 carbons and 5 double bonds), which is then used to make DHA (22 carbons and 6 double bonds). The ability to make the longer-chain omega−3 fatty acids from ALA may be impaired in aging. In foods exposed to air, unsaturated fatty acids are vulnerable to oxidation and rancidity. Dietary supplementation with omega−3 fatty acids does not appear to affect the risk of death, cancer or heart disease. Furthermore, fish oil supplement studies have failed to support claims of preventing heart attacks or strokes or any vascular disease outcomes.

Nomenclature

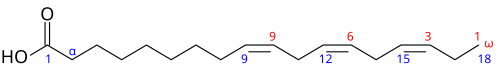

Chemical structure of α-linolenic acid (ALA), a fatty acid with a chain of 18 carbons with three double bonds

on carbons numbered 9, 12, and 15. Note that the omega (ω) end of the

chain is at carbon 18, and the double bond closest to the omega carbon

begins at carbon 15 = 18−3. Hence, ALA is a ω−3 fatty acid with ω = 18.

The terms ω–3 ("omega–3") fatty acid and n–3 fatty acid are derived from organic nomenclature. One way in which an unsaturated fatty acid is named is determined by the location, in its carbon chain, of the double bond which is closest to the methyl end of the molecule. In general terminology, n (or ω) represents the locant of the methyl end of the molecule, while the number n–x (or ω–x) refers to the locant of its nearest double bond. Thus, in omega–3

fatty acids in particular, there is a double bond located at the carbon

numbered 3, starting from the methyl end of the fatty acid chain. This

classification scheme is useful since most chemical changes occur at the

carboxyl end of the molecule, while the methyl group and its nearest double bond are unchanged in most chemical or enzymatic reactions.

In the expressions n–x or ω–x, the dash is actually meant to be a minus sign, although it is never read as such. Also, the symbol n (or ω) represents the locant of the methyl end, counted from the carboxyl

end of the fatty acid carbon chain. For instance, in an omega-3 fatty

acid with 18 carbon atoms (see illustration), where the methyl end is at

location 18 from the carboxyl end, n (or ω) represents the

number 18, and the notation n–3 (or ω–3) represents the subtraction 18–3

= 15, where 15 is the locant of the double bond which is closest to the

methyl end, counted from the carboxyl end of the chain.

Although n and ω (omega) are synonymous, the IUPAC recommends that n be used to identify the highest carbon number of a fatty acid. Nevertheless, the more common name – omega–3 fatty acid – is used in both the lay media and scientific literature.

Example

By

example, α-linolenic acid (ALA; illustration) is an 18-carbon chain

having three double bonds, the first being located at the third carbon

from the methyl end of the fatty acid chain. Hence, it is an omega–3 fatty acid. Counting from the other end of the chain, that is the carboxyl

end, the three double bonds are located at carbons 9, 12, and 15. These

three locants are typically indicated as Δ9c,12c,15c, or cisΔ9,cisΔ12,cisΔ15, or cis-cis-cis-Δ9,12,15, where c or cis means that the double bonds have a cis configuration.

α-Linolenic acid is polyunsaturated (containing more than one double bond) and is also described by a lipid number, 18:3, meaning that there are 18 carbon atoms and 3 double bonds.

Health effects

Supplementation does not appear to be associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality.

Cancer

The evidence linking the consumption of marine omega−3 fats to a lower risk of cancer is poor. With the possible exception of breast cancer, there is insufficient evidence that supplementation with omega−3 fatty acids has an effect on different cancers. The effect of consumption on prostate cancer is not conclusive. There is a decreased risk with higher blood levels of DPA, but an increased risk of more aggressive prostate cancer was shown with higher blood levels of combined EPA and DHA. In people with advanced cancer and cachexia, omega−3 fatty acids supplements may be of benefit, improving appetite, weight, and quality of life.

Cardiovascular disease

Evidence in the population generally does not support a beneficial role for omega−3 fatty acid supplementation in preventing cardiovascular disease (including myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death) or stroke. A 2018 meta-analysis found no support that daily intake of one gram of omega-3 fatty acid in individuals with a history of coronary heart disease prevents fatal coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction or any other vascular event.

However, omega−3 fatty acid supplementation greater than one gram daily

for at least a year may be protective against cardiac death, sudden

death, and myocardial infarction in people who have a history of

cardiovascular disease. No protective effect against the development of stroke or all-cause mortality was seen in this population. Eating a diet high in fish that contain long chain omega−3 fatty acids does appear to decrease the risk of stroke. Fish oil supplementation has not been shown to benefit revascularization or abnormal heart rhythms and has no effect on heart failure hospital admission rates. Furthermore, fish oil supplement studies have failed to support claims of preventing heart attacks or strokes. In the EU, a review by the European Medicines Agency

of omega-3 fatty acid medicines containing a combination of an ethyl

ester of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid at a dose of 1 g

per day concluded that these medicines are not effective in secondary

prevention of heart problems in patients who have had a myocardial

infarction.

Evidence suggests that omega−3 fatty acids modestly lower blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) in people with hypertension and in people with normal blood pressure. Some evidence suggests that people with certain circulatory problems, such as varicose veins, may benefit from the consumption of EPA and DHA, which may stimulate blood circulation and increase the breakdown of fibrin, a protein involved in blood clotting and scar formation.

Omega−3 fatty acids reduce blood triglyceride levels but do not significantly change the level of LDL cholesterol or HDL cholesterol in the blood.

The American Heart Association position (2011) is that borderline

elevated triglycerides, defined as 150–199 mg/dL, can be lowered by

0.5-1.0 grams of EPA and DHA per day; high triglycerides 200–499 mg/dL

benefit from 1-2 g/day; and >500 mg/dL be treated under a physician's

supervision with 2-4 g/day using a prescription product. In this population omega-3 fatty acid supplementation decreases the risk of heart disease by about 25%.

ALA does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits of EPA and DHAs.

The effect of omega−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on stroke is unclear, with a possible benefit in women.

Inflammation

A

2013 systematic review found tentative evidence of benefit for lowering

inflammation levels in healthy adults and in people with one or more biomarkers of metabolic syndrome. Consumption of omega−3 fatty acids from marine sources lowers blood markers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and TNF alpha.

For rheumatoid arthritis,

one systematic review found consistent, but modest, evidence for the

effect of marine n−3 PUFAs on symptoms such as "joint swelling and pain,

duration of morning stiffness, global assessments of pain and disease

activity" as well as the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The American College of Rheumatology

has stated that there may be modest benefit from the use of fish oils,

but that it may take months for effects to be seen, and cautions for

possible gastrointestinal side effects and the possibility of the

supplements containing mercury or vitamin A at toxic levels. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health has concluded that "supplements containing omega-3 fatty acids ...

may help relieve rheumatoid arthritis symptoms" and warns that such

supplements "may interact with drugs that affect blood clotting".

Developmental disabilities

Although not supported by current scientific evidence as a primary treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, and other developmental disabilities, omega−3 fatty acid supplements are being given to children with these conditions.

One meta-analysis concluded that omega−3 fatty acid supplementation demonstrated a modest effect for improving ADHD symptoms. A Cochrane review

of PUFA (not necessarily omega−3) supplementation found "there is

little evidence that PUFA supplementation provides any benefit for the

symptoms of ADHD in children and adolescents",

while a different review found "insufficient evidence to draw any

conclusion about the use of PUFAs for children with specific learning

disorders".

Another review concluded that the evidence is inconclusive for the use

of omega−3 fatty acids in behavior and non-neurodegenerative

neuropsychiatric disorders such as ADHD and depression.

Fish oil has only a small benefit on the risk of premature birth.

A 2015 meta-analysis of the effect of omega−3 supplementation during

pregnancy did not demonstrate a decrease in the rate of preterm birth or

improve outcomes in women with singleton pregnancies with no prior

preterm births.

A 2018 Cochrane systematic review with moderate to high quality of

evidence suggested that omega−3 fatty acids may reduce risk of perinatal

death, risk of low body weight babies; and possibly mildly increased LGA babies.

However, a 2019 clinical trail at Australia showed no significant

reduce on rate of preterm delivery, and no higher incidence of

interventions in post-term deliveries than control.

Mental health

There is some evidence that omega−3 fatty acids are related to mental health, including that they may tentatively be useful as an add-on for the treatment of depression associated with bipolar disorder.

Significant benefits due to EPA supplementation were only seen,

however, when treating depressive symptoms and not manic symptoms

suggesting a link between omega−3 and depressive mood. There is also preliminary evidence that EPA supplementation is helpful in cases of depression.

The link between omega−3 and depression has been attributed to the fact

that many of the products of the omega−3 synthesis pathway play key

roles in regulating inflammation (such as prostaglandin E3) which have been linked to depression. This link to inflammation regulation has been supported in both in vivo studies and in a meta-analysis.

There is, however, significant difficulty in interpreting the

literature due to participant recall and systematic differences in

diets.

There is also controversy as to the efficacy of omega−3, with many

meta-analysis papers finding heterogeneity among results which can be

explained mostly by publication bias.

A significant correlation between shorter treatment trials was

associated with increased omega−3 efficacy for treating depressed

symptoms further implicating bias in publication.

One review found that "Although evidence of benefits for any specific

intervention is not conclusive, these findings suggest that it might be

possible to delay or prevent transition to psychosis."

Cognitive aging

Epidemiological studies are inconclusive about an effect of omega−3 fatty acids on the mechanisms of Alzheimer's disease. There is preliminary evidence of effect on mild cognitive problems, but none supporting an effect in healthy people or those with dementia.

Brain and visual functions

Brain function and vision rely on dietary intake of DHA to support a broad range of cell membrane properties, particularly in grey matter, which is rich in membranes. A major structural component of the mammalian brain, DHA is the most abundant omega−3 fatty acid in the brain. It is under study as a candidate essential nutrient with roles in neurodevelopment, cognition, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Atopic diseases

Results of studies investigating the role of LCPUFA supplementation and LCPUFA status in the prevention and therapy of atopic

diseases (allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis and allergic

asthma) are controversial; therefore, at the present stage of our

knowledge (as of 2013) we cannot state either that the nutritional

intake of n−3 fatty acids has a clear preventive or therapeutic role, or

that the intake of n-6 fatty acids has a promoting role in context of

atopic diseases.

Risk of deficiency

People with PKU

often have low intake of omega−3 fatty acids, because nutrients rich in

omega−3 fatty acids are excluded from their diet due to high protein

content.

Asthma

As of 2015, there was no evidence that taking omega−3 supplements can prevent asthma attacks in children.

Chemistry

Chemical structure of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)

Chemical structure of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)

An omega−3 fatty acid is a fatty acid with multiple double bonds,

where the first double bond is between the third and fourth carbon

atoms from the end of the carbon atom chain. "Short chain" omega−3 fatty

acids have a chain of 18 carbon atoms or less, while "long chain"

omega−3 fatty acids have a chain of 20 or more.

Three omega−3 fatty acids are important in human physiology, α-linolenic acid (18:3, n-3; ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, n-3; EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6, n-3; DHA). These three polyunsaturates

have either 3, 5, or 6 double bonds in a carbon chain of 18, 20, or 22

carbon atoms, respectively. As with most naturally-produced fatty acids,

all double bonds are in the cis-configuration,

in other words, the two hydrogen atoms are on the same side of the

double bond; and the double bonds are interrupted by methylene bridges (-CH

2-), so that there are two single bonds between each pair of adjacent double bonds.

2-), so that there are two single bonds between each pair of adjacent double bonds.

List of omega−3 fatty acids

This table lists several different names for the most common omega−3 fatty acids found in nature.

| Common name | Lipid number | Chemical name |

|---|---|---|

| Hexadecatrienoic acid (HTA) | 16:3 (n-3) | all-cis-7,10,13-hexadecatrienoic acid |

| α-Linolenic acid (ALA) | 18:3 (n-3) | all-cis-9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid |

| Stearidonic acid (SDA) | 18:4 (n-3) | all-cis-6,9,12,15-octadecatetraenoic acid |

| Eicosatrienoic acid (ETE) | 20:3 (n-3) | all-cis-11,14,17-eicosatrienoic acid |

| Eicosatetraenoic acid (ETA) | 20:4 (n-3) | all-cis-8,11,14,17-eicosatetraenoic acid |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) | 20:5 (n-3) | all-cis-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoic acid |

| Heneicosapentaenoic acid (HPA) | 21:5 (n-3) | all-cis-6,9,12,15,18-heneicosapentaenoic acid |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), Clupanodonic acid |

22:5 (n-3) | all-cis-7,10,13,16,19-docosapentaenoic acid |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) | 22:6 (n-3) | all-cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-docosahexaenoic acid |

| Tetracosapentaenoic acid | 24:5 (n-3) | all-cis-9,12,15,18,21-tetracosapentaenoic acid |

| Tetracosahexaenoic acid (Nisinic acid) | 24:6 (n-3) | all-cis-6,9,12,15,18,21-tetracosahexaenoic acid |

Forms

Omega−3 fatty acids occur naturally in two forms, triglycerides and phospholipids.

In the triglycerides, they, together with other fatty acids, are bonded

to glycerol; three fatty acids are attached to glycerol. Phospholipid

omega−3 is composed of two fatty acids attached to a phosphate group via

glycerol.

The triglycerides can be converted to the free fatty acid or to

methyl or ethyl esters, and the individual esters of omega−3 fatty acids

are available.

Biochemistry

Transporters

DHA in the form of lysophosphatidylcholine is transported into the brain by a membrane transport protein, MFSD2A, which is exclusively expressed in the endothelium of the blood–brain barrier.

Mechanism of action

The

'essential' fatty acids were given their name when researchers found

that they are essential to normal growth in young children and animals.

The omega−3 fatty acid DHA, also known as docosahexaenoic acid, is found

in high abundance in the human brain. It is produced by a desaturation process, but humans lack the desaturase enzyme, which acts to insert double bonds at the ω6 and ω3 position. Therefore, the ω6 and ω3

polyunsaturated fatty acids cannot be synthesized, are appropriately

called essential fatty acids, and must be obtained from the diet.

In 1964, it was discovered that enzymes found in sheep tissues convert omega−6 arachidonic acid into the inflammatory agent, prostaglandin E2, which is involved in the immune response of traumatized and infected tissues. By 1979, eicosanoids were further identified, including thromboxanes, prostacyclins, and leukotrienes.

The eicosanoids typically have a short period of activity in the body,

starting with synthesis from fatty acids and ending with metabolism by enzymes. If the rate of synthesis exceeds the rate of metabolism, the excess eicosanoids may have deleterious effects. Researchers found that certain omega−3 fatty acids are also converted into eicosanoids and docosanoids, but at a slower rate. If both omega−3 and omega−6 fatty acids are present, they will "compete" to be transformed, so the ratio of long-chain omega−3:omega−6 fatty acids directly affects the type of eicosanoids that are produced.

Interconversion

Conversion efficiency of ALA to EPA and DHA

Humans can convert short-chain omega−3 fatty acids to long-chain forms (EPA, DHA) with an efficiency below 5%. The omega−3 conversion efficiency is greater in women than in men, but less studied.

Higher ALA and DHA values found in plasma phospholipids of women may be

due to the higher activity of desaturases, especially that of

delta-6-desaturase.

These conversions occur competitively with omega−6 fatty acids,

which are essential closely related chemical analogues that are derived

from linoleic acid. They both utilize the same desaturase and elongase

proteins in order to synthesize inflammatory regulatory proteins.

The products of both pathways are vital for growth making a balanced

diet of omega−3 and omega−6 important to an individual's health.

A balanced intake ratio of 1:1 was believed to be ideal in order for

proteins to be able to synthesize both pathways sufficiently, but this

has been controversial as of recent research.

The conversion of ALA to EPA and further to DHA in humans has been reported to be limited, but varies with individuals. Women have higher ALA-to-DHA conversion efficiency than men, which is presumed

to be due to the lower rate of use of dietary ALA for beta-oxidation.

One preliminary study showed that EPA can be increased by lowering the

amount of dietary linoleic acid, and DHA can be increased by elevating

intake of dietary ALA.

Omega−6 to omega−3 ratio

Human diet has changed rapidly in recent centuries resulting in a reported increased diet of omega−6 in comparison to omega−3. The rapid evolution of human diet away from a 1:1 omega−3 and omega−6 ratio, such as during the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution,

has presumably been too fast for humans to have adapted to biological

profiles adept at balancing omega−3 and omega−6 ratios of 1:1. This is commonly believed to be the reason why modern diets are correlated with many inflammatory disorders.

While omega−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids may be beneficial in

preventing heart disease in humans, the level of omega−6 polyunsaturated

fatty acids (and, therefore, the ratio) does not matter.

Both omega−6 and omega−3 fatty acids are essential: humans must

consume them in their diet. Omega−6 and omega−3 eighteen-carbon

polyunsaturated fatty acids compete for the same metabolic enzymes, thus

the omega−6:omega−3 ratio of ingested fatty acids has significant

influence on the ratio and rate of production of eicosanoids, a group of

hormones intimately involved in the body's inflammatory and homeostatic

processes, which include the prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and thromboxanes, among others. Altering this ratio can change the body's metabolic and inflammatory state. In general, grass-fed animals accumulate more omega−3 than do grain-fed animals, which accumulate relatively more omega−6. Metabolites

of omega−6 are more inflammatory (esp. arachidonic acid) than those of

omega−3. This necessitates that omega−6 and omega−3 be consumed in a

balanced proportion; healthy ratios of omega−6:omega−3, according to

some authors, range from 1:1 to 1:4. Other authors believe that a ratio of 4:1 (4 times as much omega−6 as omega−3) is already healthy.

Studies suggest the evolutionary human diet, rich in game animals,

seafood, and other sources of omega−3, may have provided such a ratio.

Typical Western diets provide ratios of between 10:1 and 30:1 (i.e., dramatically higher levels of omega−6 than omega−3). The ratios of omega−6 to omega−3 fatty acids in some common vegetable oils are: canola 2:1, hemp 2–3:1, soybean 7:1, olive 3–13:1, sunflower (no omega−3), flax 1:3, cottonseed (almost no omega−3), peanut (no omega−3), grapeseed oil (almost no omega−3) and corn oil 46:1.

History

Although

omega−3 fatty acids have been known as essential to normal growth and

health since the 1930s, awareness of their health benefits has

dramatically increased since the 1980s.

On September 8, 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave

"qualified health claim" status to EPA and DHA omega−3 fatty acids,

stating, "supportive but not conclusive research shows that consumption

of EPA and DHA [omega−3] fatty acids may reduce the risk of coronary

heart disease". This updated and modified their health risk advice letter of 2001 (see below).

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has recognized the importance

of DHA omega−3 and permits the following claim for DHA: "DHA, an

omega−3 fatty acid, supports the normal physical development of the

brain, eyes and nerves primarily in children under two years of age."

Historically, whole food diets contained sufficient amounts of omega−3, but because omega−3 is readily oxidized, the trend to shelf-stable, processed foods has led to a deficiency in omega−3 in manufactured foods.

Dietary sources

| Common name | grams omega−3 |

|---|---|

| Flax | 11.4 |

| Hemp | 11.0 |

| Herring, sardines | 1.3–2 |

| Mackerel: Spanish/Atlantic/Pacific | 1.1–1.7 |

| Salmon | 1.1–1.9 |

| Halibut | 0.60–1.12 |

| Tuna | 0.21–1.1 |

| Swordfish | 0.97 |

| Greenshell/lipped mussels | 0.95 |

| Tilefish | 0.9 |

| Tuna (canned, light) | 0.17–0.24 |

| Pollock | 0.45 |

| Cod | 0.15–0.24 |

| Catfish | 0.22–0.3 |

| Flounder | 0.48 |

| Grouper | 0.23 |

| Mahi mahi | 0.13 |

| Red snapper | 0.29 |

| Shark | 0.83 |

| King mackerel | 0.36 |

| Hoki (blue grenadier) | 0.41 |

| Gemfish | 0.40 |

| Blue eye cod | 0.31 |

| Sydney rock oysters | 0.30 |

| Tuna, canned | 0.23 |

| Snapper | 0.22 |

| Eggs, large regular | 0.109 |

| Strawberry or Kiwifruit | 0.10–0.20 |

| Broccoli | 0.10–0.20 |

| Barramundi, saltwater | 0.100 |

| Giant tiger prawn | 0.100 |

| Lean red meat | 0.031 |

| Turkey | 0.030 |

| Milk, regular | 0.00 |

Dietary recommendations

In the United States, the Institute of Medicine publishes a system of Dietary Reference Intakes,

which includes Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for individual

nutrients, and Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs) for

certain groups of nutrients, such as fats. When there is insufficient

evidence to determine an RDA, the institute may publish an Adequate Intake (AI) instead, which has a similar meaning, but is less certain. The AI for α-linolenic acid

is 1.6 grams/day for men and 1.1 grams/day for women, while the AMDR is

0.6% to 1.2% of total energy. Because the physiological potency of EPA

and DHA is much greater than that of ALA, it is not possible to estimate

one AMDR for all omega−3 fatty acids. Approximately 10 percent of the

AMDR can be consumed as EPA and/or DHA.[107]

The Institute of Medicine has not established a RDA or AI for EPA, DHA

or the combination, so there is no Daily Value (DVs are derived from

RDAs), no labeling of foods or supplements as providing a DV percentage

of these fatty acids per serving, and no labeling a food or supplement

as an excellent source, or "High in..." As for safety, there was insufficient evidence as of 2005 to set an upper tolerable limit for omega−3 fatty acids,

although the FDA has advised that adults can safely consume up to a

total of 3 grams per day of combined DHA and EPA, with no more than 2 g

from dietary supplements.

The American Heart Association

(AHA) has made recommendations for EPA and DHA due to their

cardiovascular benefits: individuals with no history of coronary heart

disease or myocardial infarction should consume oily fish two times per

week; and "Treatment is reasonable" for those having been diagnosed with

coronary heart disease. For the latter the AHA does not recommend a

specific amount of EPA + DHA, although it notes that most trials were at

or close to 1000 mg/day. The benefit appears to be on the order of a 9%

decrease in relative risk. The European Food Safety Authority

(EFSA) approved a claim "EPA and DHA contributes to the normal function

of the heart" for products that contain at least 250 mg EPA + DHA. The

report did not address the issue of people with pre-existing heart

disease. The World Health Organization

recommends regular fish consumption (1-2 servings per week, equivalent

to 200 to 500 mg/day EPA + DHA) as protective against coronary heart

disease and ischaemic stroke.

Contamination

Heavy metal poisoning by the body's accumulation of traces of heavy metals, in particular mercury, lead, nickel, arsenic, and cadmium, is a possible risk from consuming fish oil supplements.

Also, other contaminants (PCBs, furans, dioxins, and PBDEs) might be found, especially in less-refined fish oil supplements.

However, heavy metal toxicity from consuming fish oil supplements is

highly unlikely, because heavy metals selectively bind with protein in

the fish flesh rather than accumulate in the oil.

Throughout their history, the Council for Responsible Nutrition and the World Health Organization

have published acceptability standards regarding contaminants in fish

oil. The most stringent current standard is the International Fish Oils

Standard. Fish oils that are molecularly distilled under vacuum typically make this highest-grade; levels of contaminants are stated in parts per billion per trillion.

Fish

The most widely available dietary source of EPA and DHA is oily fish, such as salmon, herring, mackerel, anchovies, menhaden, and sardines. Oils from these fish have a profile of around seven times as much omega−3 as omega−6. Other oily fish, such as tuna, also contain n-3 in somewhat lesser amounts. Consumers of oily fish should be aware of the potential presence of heavy metals and fat-soluble pollutants like PCBs and dioxins, which are known to accumulate up the food chain. After extensive review, researchers from Harvard's School of Public Health in the Journal of the American Medical Association (2006) reported that the benefits of fish intake generally far outweigh the

potential risks. Although fish are a dietary source of omega−3 fatty

acids, fish do not synthesize them; they obtain them from the algae (microalgae in particular) or plankton in their diets.

In the case of farmed fish, omega-3 fatty acids are provided by fish

oil; In 2009, 81% of the global fish oil production is used by

aquaculture.

Fish oil

Fish oil capsules

Marine and freshwater fish oil vary in content of arachidonic acid, EPA and DHA. They also differ in their effects on organ lipids.

Not all forms of fish oil may be equally digestible. Of four

studies that compare bioavailability of the glyceryl ester form of fish

oil vs. the ethyl ester

form, two have concluded the natural glyceryl ester form is better, and

the other two studies did not find a significant difference. No studies

have shown the ethyl ester form to be superior, although it is cheaper

to manufacture.

Krill

Krill oil is a source of omega−3 fatty acids.

The effect of krill oil, at a lower dose of EPA + DHA (62.8%), was

demonstrated to be similar to that of fish oil on blood lipid levels and

markers of inflammation in healthy humans. While not an endangered species,

krill are a mainstay of the diets of many ocean-based species including

whales, causing environmental and scientific concerns about their

sustainability.

Preliminary studies appear to indicate that the DHA and EPA omega-3 fatty acids found in krill oil may be more bio-available than in fish oil. Additionally, krill oil contains astaxanthin, a marine-source keto-carotenoid antioxidant that may act synergistically with EPA and DHA.

Plant sources

Chia is grown commercially for its seeds rich in ALA.

Flax seeds contain linseed oil which has high ALA content

Table 1. ALA content as the percentage of the seed oil.

| Common name | Alternative name | Linnaean name | % ALA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kiwifruit seed oil | Chinese gooseberry | Actinidia deliciosa | 63 |

| Perilla | shiso | Perilla frutescens | 61 |

| Chia seed | chia sage | Salvia hispanica | 58 |

| Flax | linseed | Linum usitatissimum | 53 – 59 |

| Lingonberry | Cowberry | Vaccinium vitis-idaea | 49 |

| Fig seed oil | Common Fig | Ficus carica | 47.7 |

| Camelina | Gold-of-pleasure | Camelina sativa | 36 |

| Purslane | Portulaca | Portulaca oleracea | 35 |

| Black raspberry | Rubus occidentalis | 33 | |

| Hemp | Cannabis sativa | 19 | |

| Canola | Rapeseed oil | mostly Brassica napus | 9 – 11 |

Table 2. ALA content as the percentage of the whole food.

| Common name | Linnaean name | % ALA |

|---|---|---|

| Flaxseed | Linum usitatissimum | 18.1 |

| Hempseed | Cannabis sativa | 8.7 |

| Butternuts | Juglans cinerea | 8.7 |

| Persian walnuts | Juglans regia | 6.3 |

| Pecan nuts | Carya illinoinensis | 0.6 |

| Hazel nuts | Corylus avellana | 0.1 |

Flaxseed (or linseed) (Linum usitatissimum) and its oil are perhaps the most widely available botanical source of the omega−3 fatty acid ALA. Flaxseed oil consists of approximately 55% ALA, which makes it six times richer than most fish oils in omega−3 fatty acids.

A portion of this is converted by the body to EPA and DHA, though the

actual converted percentage may differ between men and women.

In 2013 Rothamsted Research in the UK reported they had developed a genetically modified form of the plant Camelina

that produced EPA and DHA. Oil from the seeds of this plant contained

on average 11% EPA and 8% DHA in one development and 24% EPA in another.

Eggs

Eggs produced

by hens fed a diet of greens and insects contain higher levels of

omega−3 fatty acids than those produced by chickens fed corn or

soybeans. In addition to feeding chickens insects and greens, fish oils may be added to their diets to increase the omega−3 fatty acid concentrations in eggs.

The addition of flax and canola seeds to the diets of chickens,

both good sources of alpha-linolenic acid, increases the omega−3 content

of the eggs, predominantly DHA.

The addition of green algae or seaweed to the diets boosts the

content of DHA and EPA, which are the forms of omega−3 approved by the

FDA for medical claims. A common consumer complaint is "Omega−3 eggs can

sometimes have a fishy taste if the hens are fed marine oils".

Meat

Omega−3 fatty

acids are formed in the chloroplasts of green leaves and algae. While

seaweeds and algae are the source of omega−3 fatty acids present in

fish, grass is the source of omega−3 fatty acids present in grass fed

animals.

When cattle are taken off omega−3 fatty acid rich grass and shipped to a

feedlot to be fattened on omega−3 fatty acid deficient grain, they

begin losing their store of this beneficial fat. Each day that an animal

spends in the feedlot, the amount of omega−3 fatty acids in its meat is

diminished.

The omega−6:omega−3 ratio of grass-fed beef is about 2:1, making it a more useful source of omega−3 than grain-fed beef, which usually has a ratio of 4:1.

In a 2009 joint study by the USDA and researchers at Clemson

University in South Carolina, grass-fed beef was compared with

grain-finished beef. The researchers found that grass-finished beef is

higher in moisture content, 42.5% lower total lipid content, 54% lower

in total fatty acids, 54% higher in beta-carotene, 288% higher in

vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol), higher in the B-vitamins thiamin and

riboflavin, higher in the minerals calcium, magnesium, and potassium,

193% higher in total omega−3s, 117% higher in CLA (cis-9, trans-11

octadecenoic acid, a conjugated linoleic acid, which is a potential

cancer fighter), 90% higher in vaccenic acid (which can be transformed

into CLA), lower in the saturated fats, and has a healthier ratio of

omega−6 to omega−3 fatty acids (1.65 vs 4.84). Protein and cholesterol

content were equal.

The omega−3 content of chicken meat may be enhanced by increasing the animals' dietary intake of grains high in omega−3, such as flax, chia, and canola.

Kangaroo meat is also a source of omega−3, with fillet and steak containing 74 mg per 100 g of raw meat.

Seal oil

Seal oil is a source of EPA, DPA, and DHA. According to Health Canada, it helps to support the development of the brain, eyes, and nerves in children up to 12 years of age. Like all seal products, it is not allowed to be imported into the European Union.

Other sources

A trend in the early 21st century was to fortify food with omega−3 fatty acids. The microalgae Crypthecodinium cohnii and Schizochytrium are rich sources of DHA, but not EPA, and can be produced commercially in bioreactors for use as food additives. Oil from brown algae (kelp) is a source of EPA. The alga Nannochloropsis also has high levels of EPA.