International human rights law (IHRL) is the body of international law designed to promote human rights

on social, regional, and domestic levels. As a form of international

law, international human rights law are primarily made up of treaties, agreements between sovereign states intended to have binding legal effect between the parties that have agreed to them; and customary international law. Other international human rights instruments,

while not legally binding, contribute to the implementation,

understanding and development of international human rights law and have

been recognized as a source of political obligation.

The relationship between international human rights law and international humanitarian law is disputed among international law scholars. This discussion forms part of a larger discussion on fragmentation of international law. While pluralist scholars conceive international human rights law as being distinct from international humanitarian law, proponents of the constitutionalist approach regard the latter as a subset of the former. In a nutshell, those who favors separate, self-contained regimes emphasize the differences in applicability; international humanitarian law applies only during armed conflict.

A more systemic perspective explains that international humanitarian law represents a function of international human rights law; it includes general norms that apply to everyone at all time as well as specialized norms which apply to certain situations such as armed conflict between both state and military occupation (i.e. IHL) or to certain groups of people including refugees (e.g. the 1951 Refugee Convention), children (the Convention on the Rights of the Child), and prisoners of war (the 1949 Third Geneva Convention).

The relationship between international human rights law and international humanitarian law is disputed among international law scholars. This discussion forms part of a larger discussion on fragmentation of international law. While pluralist scholars conceive international human rights law as being distinct from international humanitarian law, proponents of the constitutionalist approach regard the latter as a subset of the former. In a nutshell, those who favors separate, self-contained regimes emphasize the differences in applicability; international humanitarian law applies only during armed conflict.

A more systemic perspective explains that international humanitarian law represents a function of international human rights law; it includes general norms that apply to everyone at all time as well as specialized norms which apply to certain situations such as armed conflict between both state and military occupation (i.e. IHL) or to certain groups of people including refugees (e.g. the 1951 Refugee Convention), children (the Convention on the Rights of the Child), and prisoners of war (the 1949 Third Geneva Convention).

United Nations system

The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action in 1993, in terms of which the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights was established.

In 2006, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights was replaced with the United Nations Human Rights Council

for the enforcement of international human rights law. The changes

prophesied a more structured organization along with a requirement to

review human rights cases every 4 years.

International Bill of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

(UDHR) is a UN General Assembly declaration that does not in form

create binding international human rights law. Many legal scholars cite

the UDHR as evidence of customary international law.

More broadly, the UDHR has become an authoritative human rights reference. It has provided the basis for subsequent international human rights instruments that form non-binding, but ultimately authoritative international human rights law.

International human rights treaties

Besides the adoption in 1966 of the two wide-ranging Covenants that form part of the International Bill of Human Rights (namely the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), other treaties have been adopted at the international level. These are generally known as human rights instruments. Some of the most significant include the following:

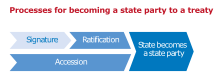

- the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPCG) (adopted 1948 and entered into force in 1951);Processes for becoming a state party to a treaty

- the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (CSR) (adopted in 1951 and entered into force in 1954);

- the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) (adopted in 1965 and entered into force in 1969);

- the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (entered into force in 1981);

- the United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT) (adopted in 1984 and entered into force in 1987);

- the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (adopted in 1989 and entered into force in 1990);

- the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW) (adopted in 1990 and entered into force in 2003);

- the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (entered into force on 3 May 2008); and

- the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED) (adopted in 2006 and entered into force in 2010).

Regional protection and institutions

Regional

systems of international human rights law supplement and complement

national and international human rights law by protecting and promoting

human rights in specific areas of the world. There are three key

regional human rights instruments which have established human rights

law on a regional basis:

- the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights for Africa of 1981, in force since 1986;

- the American Convention on Human Rights for the Americas of 1969, in force since 1978; and

- the European Convention on Human Rights for Europe of 1950, in force since 1953.

Americas and Europe

The Organisation of American States and the Council of Europe, like the UN, have adopted treaties (albeit with weaker implementation mechanisms) containing catalogues of economic, social and cultural rights, in addition to the aforementioned conventions dealing mostly with civil and political rights:

- the European Social Charter for Europe of 1961, in force since 1965 (whose complaints mechanism, created in 1995 under an Additional Protocol, has been in force since 1998); and

- the Protocol of San Salvador to the ACHR for the Americas of 1988, in force since 1999.

Africa

The African Union (AU) is a supranational union consisting of 53 African countries.

Established in 2001, the AU's purpose is to help secure Africa's

democracy, human rights, and a sustainable economy, in particular by

bringing an end to intra-African conflict and creating an effective

common market.

The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights is the region's principal human rights instrument, which emerged under the aegis of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) (since replaced by the African Union). The intention to draw up the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights was announced in 1979. The Charter was unanimously approved at the OAU's 1981 Assembly.

Pursuant to Article 63 (whereby it was to "come into force three

months after the reception by the Secretary General of the instruments

of ratification or adherence of a simple majority" of the OAU's member

states), the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights came into

effect on 21 October 1986, in honour of which 21 October was declared African Human Rights Day.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) is a quasi-judicial organ of the African Union,

tasked with promoting and protecting human rights and collective

(peoples') rights throughout the African continent, as well as with

interpreting the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, and

considering individual complaints of violations of the Charter. The

Commission has three broad areas of responsibility:

- promoting human and peoples' rights;

- protecting human and peoples' rights; and

- interpreting the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights.

In pursuit of these goals, the Commission is mandated to "collect

documents, undertake studies and researches on African problems in the

field of human and peoples' rights, organise seminars, symposia and

conferences, disseminate information, encourage national and local

institutions concerned with human and peoples' rights and, should the

case arise, give its views or make recommendations to governments."

With the creation of the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights

(under a protocol to the Charter which was adopted in 1998 and entered

into force in January 2004), the Commission will have the additional

task of preparing cases for submission to the Court's jurisdiction.

In a July 2004 decision, the AU Assembly resolved that the future Court

on Human and Peoples' Rights would be integrated with the African Court

of Justice.

The Court of Justice of the African Union is intended to be the "principal judicial organ of the Union."

Although it has not yet been established, it is intended to take over

the duties of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, as

well as to act as the supreme court of the African Union, interpreting

all necessary laws and treaties. The Protocol establishing the African

Court on Human and Peoples' Rights entered into force in January 2004,

but its merging with the Court of Justice has delayed its

establishment. The Protocol establishing the Court of Justice will come

into force when ratified by fifteen countries.

There are many countries in Africa accused of human rights violations by the international community and NGOs.

Inter-American system

The Organization of American States

(OAS) is an international organization headquartered in Washington, DC.

Its members are the thirty-five independent nation-states of the

Americas.

Over the course of the 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, the return to democracy in Latin America, and the thrust toward globalisation, the OAS made major efforts to reinvent itself to fit the new context. Its stated priorities now include the following:

- strengthening democracy;

- working for peace;

- protecting human rights;

- combating corruption;

- the rights of indigenous peoples; and

- promoting sustainable development.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) is an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States, also based in Washington, D.C. Along with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, based in San José, Costa Rica, it is one of the bodies that comprise the inter-American system for the promotion and protection of human rights.

The IACHR is a permanent body which meets in regular and special

sessions several times a year to examine allegations of human rights

violations in the hemisphere. Its human rights duties stem from three

documents:

- the OAS Charter;

- the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man; and

- the American Convention on Human Rights.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights was established in 1979 with

the purpose of enforcing and interpreting the provisions of the

American Convention on Human Rights. Its two main functions are

therefore adjudicatory and advisory:

- Under the former, it hears and rules on the specific cases of human rights violations referred to it.

- Under the latter, it issues opinions on matters of legal interpretation brought to its attention by other OAS bodies or member states.

Many countries in the Americas, including Colombia, Cuba, Mexico and Venezuela, have been accused of human rights violations.

European system

The Council of Europe,

founded in 1949, is the oldest organisation working for European

integration. It is an international organisation with legal personality

recognised under public international law, and has observer status at

the United Nations. The seat of the Council is in Strasbourg in France.

The Council of Europe is responsible for both the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights.

These institutions bind the Council's members to a code of human rights

which, although strict, is more lenient than that of the UN Charter on

human rights.

The Council also promotes the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and the European Social Charter. Membership is open to all European states which seek European integration, accept the principle of the rule of law, and are able and willing to guarantee democracy, fundamental human rights and freedoms.

The Council of Europe is separate from the European Union, but the latter is expected to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. The Council includes all the member states of European Union. The EU also has a separate human rights document, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

The European Convention on Human Rights has since 1950 defined and guaranteed human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe.

All 47 member states of the Council of Europe have signed this

Convention, and are therefore under the jurisdiction of the European

Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. In order to prevent torture and inhuman or degrading treatment, the Committee for the Prevention of Torture was established.

The Council of Europe also adopted the Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings in May 2005, for protection against human trafficking and sexual exploitation, the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse in October 2007, and the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence in May 2011.

The European Court of Human Rights is the only international court with jurisdiction to deal with cases brought by individuals rather than states. In early 2010, the court had a backlog of over 120,000 cases and a multi-year waiting list. About one out of every twenty cases submitted to the court is considered admissible. In 2007, the court issued 1,503 verdicts. At the current rate of proceedings, it would take 46 years for the backlog to clear.

Monitoring, implementation and enforcement

There

is currently no international court to administer international human

rights law, but quasi-judicial bodies exist under some UN treaties (like

the Human Rights Committee under the ICCPR). The International Criminal Court (ICC) has jurisdiction over the crime of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The European Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights enforce regional human rights law.

Although these same international bodies also hold jurisdiction

over cases regarding international humanitarian law, it is crucial to

recognise, as discussed above, that the two frameworks constitute

different legal regimes.

The United Nations human rights bodies do have some quasi-legal

enforcement mechanisms. These include the treaty bodies attached to the

seven currently active treaties, and the United Nations Human Rights Council complaints procedures, with Universal Periodic Review and United Nations Special Rapporteur (known as the 1235 and 1503 mechanisms respectively).

The enforcement of international human rights law is the responsibility of the nation state; it is the primary responsibility of the State to make the human rights of its citizens a reality.

In practice, many human rights are difficult to enforce legally,

due to the absence of consensus on the application of certain rights,

the lack of relevant national legislation or of bodies empowered to take

legal action to enforce them.

In over 110 countries, national human rights institutions (NHRIs) have been set up to protect, promote or monitor human rights with jurisdiction in a given country. Although not all NHRIs are compliant with the Paris Principles, the number and effect of these institutions is increasing.

The Paris Principles

were defined at the first International Workshop on National

Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in Paris

from 7 to 9 October 1991, and adopted by UN Human Rights Commission

Resolution 1992/54 of 1992 and General Assembly Resolution 48/134 of

1993. The Paris Principles list a number of responsibilities for national human rights institutions.

Universal jurisdiction

Universal jurisdiction

is a controversial principle in international law, whereby states claim

criminal jurisdiction over people whose alleged crimes were committed

outside the boundaries of the prosecuting state, regardless of

nationality, country of residence or any other relationship to the

prosecuting country. The state backs its claim on the grounds that the

crime committed is considered a crime against all, which any state is

authorized to punish. The concept of universal jurisdiction is therefore closely linked to the idea that certain international norms are erga omnes, or owed to the entire world community, as well as the concept of jus cogens.

In 1993, Belgium

passed a "law of universal jurisdiction" to give its courts

jurisdiction over crimes against humanity in other countries. In 1998, Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London following an indictment by Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón under the universal-jurisdiction principle.

The principle is supported by Amnesty International and other human rights organisations,

which believe that certain crimes pose a threat to the international

community as a whole, and that the community has a moral duty to act.

Others, like Henry Kissinger,

argue that "widespread agreement that human rights violations and

crimes against humanity must be prosecuted has hindered active

consideration of the proper role of international courts. Universal

jurisdiction risks creating universal tyranny—that of judges".