A family support centre in Saint Peter Port, Guernsey, which provides assistance to families with children.

Welfare is a type of government support for the citizens of

that society. Welfare may be provided to people of any income level, as

with social security (and is then often called a social safety net),

but it is usually intended to ensure that people can meet their basic

human needs such as food and shelter. Welfare attempts to provide a

minimal level of well-being, usually either a free- or a subsidized-supply of certain goods and social services, such as healthcare, education, and vocational training.

A welfare state

is a political system wherein the State assumes responsibility for the

health, education, and welfare of society. The system of social security

in a welfare state provides social services, such as universal medical care, unemployment insurance for workers, financial aid, free post-secondary education for students, subsidized public housing, and pensions (sickness, incapacity, old-age), etc. In 1952, with the Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention (nr. 102), the International Labour Organization (ILO) formally defined the social contingencies covered by social security.

The first welfare state was Imperial Germany (1871–1918), where the Bismarck government introduced social security in 1889. In the early 20th century, the United Kingdom introduced social security around 1913, and adopted the welfare state with the National Insurance Act 1946, during the Attlee government (1945–51). In the countries of western Europe, Scandinavia, and Australasia, social welfare is mainly provided by the government out of the national tax revenues, and to a lesser extent by non-government organizations (NGOs), and charities (social and religious).

Terminology

In the U.S., welfare program is the general term for government support of the well-being of poor people, and the term social security has come to be referred to as US social insurance program for retired and disabled people even though social security

is itself a retirement insurance plan paid for by taxes taken from the

individual worker's payroll check and matched by his employer, no part

of it is paid by the Federal Government. In other countries, the term social security

has a broader definition, which refers to the economic security that a

society offers when people are sick, disabled, and unemployed. In the

U.K., government use of the term welfare includes help for poor people and benefits, including specific social services such as help in finding employment.

History

Distributing alms to the poor, abbey of Port-Royal des Champs c. 1710.

In the Roman Empire, the first emperor Augustus provided the Cura Annonae or grain dole for citizens who could not afford to buy food every month. Social welfare was enlarged by the Emperor Trajan. Trajan's program brought acclaim from many, including Pliny the Younger. The Song dynasty

government (c.1000AD in China) supported multiple programs which could

be classified as social welfare, including the establishment of

retirement homes, public clinics, and paupers' graveyards. According to

economist Robert Henry Nelson, "The medieval Roman Catholic Church operated a far-reaching and comprehensive welfare system for the poor..."

The modern study of social welfare has been proposed as an

interdisciplinary approach including theology, sociology, and economics

to understand why earlier societies evolved different institutions prior

to the welfare state.

Early welfare programs in Europe included the English Poor Law of 1601, which gave parishes the responsibility for providing welfare payments to the poor. This system was substantially modified by the 19th-century Poor Law Amendment Act, which introduced the system of workhouses.

The writers of the United States Constitution (created 1787,

ratified 1788, adopted 1789) placed "promoting general welfare" as a

specific objective for establishing the United States in the Preamble to the United States Constitution.

The Powers of Congress (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 1), specifically

grants the federal government the power to "collect taxes [for] the

general welfare of the United States". "We the People of the United

States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure

domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare,

and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do

ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of

America." "The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes,

Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States".

Public assistance programs were not called welfare until the early 20th century when the term was quickly adopted to avoid the negative connotations that had become associated with older terms such as charity.

It was predominantly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

that an organized system of state welfare provision was introduced in

many countries. Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of Germany, introduced one of the first welfare systems for the working classes. In Great Britain the Liberal government of Henry Campbell-Bannerman and David Lloyd George introduced the National Insurance system in 1911, a system later expanded by Clement Attlee. The United States inherited England's poor house laws and has had a form of welfare since before it won its independence. During the Great Depression, when emergency relief measures were introduced under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Roosevelt's New Deal focused predominantly on a program of providing work and stimulating the economy through public spending on projects, rather than on cash payment.

Modern welfare states include Germany, France, the Netherlands, as well as the Nordic countries, such as Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland which employ a system known as the Nordic model.

Esping-Andersen classified the most developed welfare state systems

into three categories; Social Democratic, Conservative, and Liberal.

In the Islamic world, Zakat (charity), one of the Five Pillars of Islam, has been collected by the government since the time of the Rashidun caliph Umar in the 7th century. The taxes were used to provide income for the needy, including the poor, elderly, orphans, widows, and the disabled. According to the Islamic jurist Al-Ghazali (Algazel, 1058–111), the government was also expected to store up food supplies in every region in case a disaster or famine occurred.

The World Bank's 2019 World Development Report on The Changing Nature of Work

considers whether traditional social assistance models continue to be

appropriate given that, in 2018, 8 in 10 people in developing countries

still receive no social assistance while 6 in 10 work informally beyond

the government's reach.

According to a 2012 review study, whether a welfare program generates public support depends on:

- whether the program is universal or targeted towards certain groups

- the size of the social program benefits (larger benefits incentivize greater mobilization to defend a social program)

- the visibility and traceability of the benefits (whether recipients know where the benefits come from)

- the proximity and concentration of the beneficiaries (this affects the ease by which beneficiaries can organize to protect a social program)

- the duration of the benefits (longer benefits incentivize greater mobilization to defend a social program)

- the manner in which a program is administered (e.g. is the program inclusive, does it follow principles?)

Forms

Welfare can take a variety of forms, such as monetary payments, subsidies and vouchers,

or housing assistance. Welfare systems differ from country to country,

but welfare is commonly provided to individuals who are unemployed, those with illness or disability, the elderly, those with dependent children, and veterans. A person's eligibility for welfare may also be constrained by means testing or other conditions.

Provision and funding

Welfare

is provided by governments or their agencies, by private organizations,

or a combination of both. Funding for welfare usually comes from

general government revenue, but when dealing with charities or NGOs, donations may be used. Some countries run conditional cash transfer welfare programs where payment is conditional on behavior of the recipients.

Welfare systems

Australia

Prior to 1900 in Australia, charitable assistance from benevolent

societies, sometimes with financial contributions from the authorities,

was the primary means of relief for people not able to support

themselves. The 1890s economic depression and the rise of the trade unions and the Labor parties during this period led to a movement for welfare reform.

In 1900, the states of New South Wales and Victoria enacted

legislation introducing non-contributory pensions for those aged 65 and

over. Queensland legislated a similar system in 1907 before the

Australian labor Commonwealth government led by Andrew Fisher

introduced a national aged pension under the Invalid and Old-Aged

Pensions Act 1908. A national invalid disability pension was started in

1910, and a national maternity allowance was introduced in 1912.

During the Second World War, Australia under a labor government created a welfare state

by enacting national schemes for: child endowment in 1941 (superseding

the 1927 New South Wales scheme); a widows’ pension in 1942 (superseding

the New South Wales 1926 scheme); a wife's allowance in 1943;

additional allowances for the children of pensioners in 1943; and

unemployment, sickness, and special benefits in 1945 (superseding the

Queensland 1923 scheme).

Canada

Canada has a welfare state

in the European tradition; however, it is not referred to as "welfare",

but rather as "social programs". In Canada, "welfare" usually refers

specifically to direct payments to poor individuals (as in the American

usage) and not to healthcare and education spending (as in the European

usage).

The Canadian social safety net covers a broad spectrum of programs, and because Canada is a federation, many are run by the provinces. Canada has a wide range of government transfer payments to individuals, which totaled $145 billion in 2006. Only social programs that direct funds to individuals are included in that cost; programs such as medicare and public education are additional costs.

Generally speaking, before the Great Depression,

most social services were provided by religious charities and other

private groups. Changing government policy between the 1930s and 1960s

saw the emergence of a welfare state, similar to many Western European

countries. Most programs from that era are still in use, although many

were scaled back during the 1990s as government priorities shifted

towards reducing debt and deficits.

Denmark

Danish

welfare is handled by the state through a series of policies (and the

like) that seeks to provide welfare services to citizens, hence the term

welfare state. This refers not only to social benefits, but also

tax-funded education, public child care, medical care, etc. A number of

these services are not provided by the state directly, but administered

by municipalities, regions or private providers through outsourcing. This sometimes gives a source of tension between the state and municipalities,

as there is not always consistency between the promises of welfare

provided by the state (i.e. parliament) and local perception of what it

would cost to fulfill these promises.

France

Solidarity

is a strong value of the French Social Protection system. The first

article of the French Code of Social Security describes the principle of

solidarity. Solidarity is commonly comprehended in relations of similar

work, shared responsibility and common risks. Existing solidarities in

France caused the expansion of health and social security.

Germany

The welfare state has a long tradition in Germany dating back to the industrial revolution. Due to the pressure of the workers' movement in the late 19th century, Reichskanzler Otto von Bismarck introduced the first rudimentary state social insurance scheme. Under Adolf Hitler, the National Socialist Program

stated "We demand an expansion on a large scale of old age welfare".

Today, the social protection of all its citizens is considered a central

pillar of German national policy. 27.6 percent of Germany's GDP is channeled into an all-embracing system of health, pension, accident, longterm care and unemployment insurance, compared to 16.2 percent in the US. In addition, there are tax-financed services such as child benefits (Kindergeld, beginning at €192

per month for the first and second child, €198 for the third and €223

for each child thereafter, until they attain 25 years or receive their

first professional qualification), and basic provisions for those unable to work or anyone with an income below the poverty line.

Since 2005, reception of full unemployment pay (60–67% of the previous net salary) has been restricted to 12 months in general and 18 months for those over 55. This is now followed by (usually much lower) Arbeitslosengeld II (ALG II) or Sozialhilfe, which is independent of previous employment (Hartz IV concept).

Under ALG II, a single person receives €391 per month plus the cost of 'adequate' housing and health insurance. ALG II can also be paid partially to supplement a low work income.

Italy

The Italian welfare state's foundations were laid along the lines of the corporatist-conservative model, or of its Mediterranean variant. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, increases in public spending and a major focus on universality brought it on the same path as social-democratic

systems. In 1978, a universalistic welfare model was introduced in

Italy, offering a number of universal and free services such as a

National Health Fund.

Japan

Social welfare, assistance for the ill or otherwise disabled and for the old, has long been provided in Japan

by both the government and private companies. Beginning in the 1920s,

the government enacted a series of welfare programs, based mainly on

European models, to provide medical care and financial support. During

the postwar period, a comprehensive system of social security was

gradually established.

Latin America

History

The 1980s marked a change in the structure of Latin American

social protection programs. Social protection embraces three major

areas: social insurance, financed by workers and employers; social

assistance to the population's poorest, financed by the state; and labor

market regulations to protect worker rights. Although diverse, recent Latin American social policy has tended to concentrate on social assistance.

The 1980s had a significant effect on social protection policies.

Prior to the 1980s, most Latin American countries focused on social

insurance policies involving formal sector workers, assuming that the informal sector would disappear with economic development. The economic crisis of the 1980s and the liberalization of the labor market

led to a growing informal sector and a rapid increase in poverty and

inequality. Latin American countries did not have the institutions and

funds to properly handle such a crisis, both due to the structure of the

social security system, and to the previously implemented structural adjustment policies (SAPs) that had decreased the size of the state.

New Welfare programs have integrated the multidimensional, social risk management,

and capabilities approaches into poverty alleviation. They focus on

income transfers and service provisions while aiming to alleviate both

long- and short-term poverty through, among other things, education,

health, security, and housing. Unlike previous programs that targeted

the working class, new programs have successfully focused on locating

and targeting the very poorest.

The impacts of social assistance programs vary between countries,

and many programs have yet to be fully evaluated. According to

Barrientos and Santibanez, the programs have been more successful in

increasing investment in human capital

than in bringing households above the poverty line. Challenges still

exist, including the extreme inequality levels and the mass scale of

poverty; locating a financial basis for programs; and deciding on exit strategies or on the long-term establishment of programs.

1980s impacts

The

economic crisis of the 1980s led to a shift in social policies, as

understandings of poverty and social programs evolved (24). New, mostly

short-term programs emerged. These include:

- Argentina: Jefes y Jefas de Hogar, Asignación Universal por Hijo

- Bolivia: Bonosol

- Brazil: Bolsa Escola and Bolsa Familia

- Chile: Chile Solidario

- Colombia: Solidaridad por Colombia

- Ecuador: Bono de Desarrollo Humano

- Honduras: Red Solidaria

- Mexico: Prospera (earlier known as Oportunidades)

- Panama: Red de Oportunidades

- Peru: Juntos

Major aspects of current social assistance programs

- Conditional cash transfer (CCT) combined with service provisions. Transfer cash directly to households, most often through the women of the household, if certain conditions are met (e.g. children's school attendance or doctor visits) (10). Providing free schooling or healthcare is often not sufficient, because there is an opportunity cost for the parents in, for example, sending children to school (lost labor power), or in paying for the transportation costs of getting to a health clinic.

- Household. The household has been the focal point of social assistance programs.

- Target the poorest. Recent programs have been more successful than past ones in targeting the poorest. Previous programs often targeted the working class.

- Multidimensional. Programs have attempted to address many dimensions of poverty at once. Chile Solidario is the best example.

New Zealand

New Zealand is often regarded as having one of the first

comprehensive welfare systems in the world. During the 1890s a Liberal

government adopted many social programmes to help the poor who had

suffered from a long economic depression in the 1880s. One of the most

far reaching was the passing of tax legislation that made it difficult

for wealthy sheep farmers to hold onto their large land holdings. This

and the invention of refrigeration led to a farming revolution where

many sheep farms were broken up and sold to become smaller dairy farms.

This enabled thousands of new farmers to buy land and develop a new and

vigorous industry that has become the backbone of New Zealand's economy to this day. This liberal tradition flourished with increased enfranchisement for indigenous Maori

in the 1880s and women. Pensions for the elderly, the poor and war

casualties followed, with State-run schools, hospitals and subsidized

medical and dental care. By 1960 New Zealand was able to afford one of

the best-developed and most comprehensive welfare systems in the world,

supported by a well-developed and stable economy.

Sweden

Social welfare in Sweden is made up of several organizations and

systems dealing with welfare. It is mostly funded by taxes, and executed

by the public sector

on all levels of government as well as private organizations. It can be

separated into three parts falling under three different ministries;

social welfare, falling under the responsibility of Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; education, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and Research and labor market, under the responsibility of Ministry of Employment.

Government pension payments are financed through an 18.5% pension

tax on all taxed incomes in the country, which comes partly from a tax category called a public pension fee (7% on gross income),

and 30% of a tax category called employer fees on salaries (which is

33% on a netted income). Since January 2001 the 18.5% is divided in two

parts: 16% goes to current payments, and 2.5% goes into individual retirement accounts, which were introduced in 2001. Money saved and invested in government funds, and IRAs for future pension costs, are roughly 5 times annual government pension expenses (725/150).

United Kingdom

- UK Government welfare expenditure 2011–12

- State pension (46.32%)

- Housing Benefit (10.55%)

- Disability Living Allowance (7.87%)

- Pension Credit (5.06%)

- Income Support (4.31%)

- Rent rebates (3.43%)

- Attendance Allowance (3.31%)

- Jobseeker's Allowance (3.06%)

- Incapacity Benefit (3.06%)

- Council Tax Benefit (3%)

- Other (10.03%)

The United Kingdom has a long history of welfare, notably including the English Poor laws which date back to 1536. After various reforms to the program, which involved workhouses, it was eventually abolished and replaced with a modern system by laws such as National Assistance Act 1948.

In more recent times, comparing the Cameron–Clegg coalition's austerity measures with the Opposition's, the respected Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf commented that the "big shift from Labour ... is the cuts in welfare benefits."

The government's austerity programme, which involves reduction in

government policy, has been linked to a rise in food banks. A study

published in the British Medical Journal in 2015 found that each 1 percentage point increase in the rate of Jobseeker's Allowance claimants sanctioned was associated with a 0.09 percentage point rise in food bank use.

The austerity programme has faced opposition from disability rights

groups for disproportionately affecting disabled people. The "bedroom tax"

is an austerity measure that has attracted particular criticism, with

activists arguing that two-thirds of council houses affected by the

policy are occupied with a person with a disability.

United States

President Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act, August 14, 1935.

In the United States, depending on the context, the term "welfare" can be used to refer to means-tested cash benefits, especially the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program and its successor, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

Block Grant, or it can be used to refer to all means-tested programs

that help individuals or families meet basic needs, including, for

example, health care through Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits and food and nutrition programs (SNAP). It can also include Social Insurance programs such as Unemployment Insurance, Social Security, and Medicare.

AFDC (originally called Aid to Dependent Children) was created

during the Great Depression to alleviate the burden of poverty for

families with children and allow widowed mothers to maintain their

households. The New Deal employment program such as the Works Progress Administration primarily served men. Prior to the New Deal, anti-poverty programs

were primarily operated by private charities or state or local

governments; however, these programs were overwhelmed by the depth of

need during the Depression. The United States has no national program of cash assistance for non-disabled poor individuals who are not raising children.

Until early in the year of 1965, the news media was conveying

only whites as living in poverty however that perception had changed to

blacks. Some of the influences in this shift could have been the civil rights movement

and urban riots from the mid 60s. Welfare had then shifted from being a

White issue to a Black issue and during this time frame the war on

poverty had already begun. Subsequently, news media portrayed stereotypes of Blacks as lazy, undeserving and welfare queens. These shifts in media don't necessarily establish the population living in poverty decreasing.

In 1996, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act

changed the structure of Welfare payments and added new criteria to

states that received Welfare funding. After reforms, which President

Clinton said would "end Welfare as we know it", amounts from the federal government were given out in a flat rate per state based on population.

Each state must meet certain criteria to ensure recipients are being

encouraged to work themselves out of Welfare. The new program is called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

It encourages states to require some sort of employment search in

exchange for providing funds to individuals, and imposes a five-year

lifetime limit on cash assistance. In FY 2010, 31.8% of TANF families were white, 31.9% were African-American, and 30.0% were Hispanic.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau data released September 13, 2011, the nation's poverty rate rose to 15.1% (46.2 million) in 2010,[51]

up from 14.3% (approximately 43.6 million) in 2009 and to its highest

level since 1993. In 2008, 13.2% (39.8 million) Americans lived in

relative poverty.

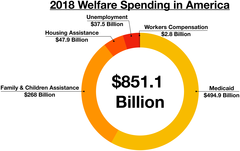

In a 2011 op-ed in Forbes,

Peter Ferrara stated that, "The best estimate of the cost of the 185

federal means tested Welfare programs for 2010 for the federal

government alone is nearly $700 billion, up a third since 2008,

according to the Heritage Foundation. Counting state spending, total

Welfare spending for 2010 reached nearly $900 billion, up nearly

one-fourth since 2008 (24.3%)". California, with 12% of the U.S. population, has one-third of the nation's welfare recipients.

In FY 2011, federal spending on means-tested welfare, plus state

contributions to federal programs, reached $927 billion per year.

Roughly half of this welfare assistance, or $462 billion went to

families with children, most of which are headed by single parents.

The United States has also typically relied on charitable giving

through non-profit agencies and fundraising instead of direct monetary

assistance from the government itself. According to Giving USA,

Americans gave $358.38 billion to charity in 2014. This is rewarded by

the United States government through tax incentives for individuals and

companies that are not typically seen in other countries.

Criticism

Income transfers can be either conditional or unconditional.

Conditionalities are sometimes criticized as being paternalistic and unnecessary.

Some opponents of welfare argue that it affects work incentives.