In psychoanalytic theory, a defence mechanism is an unconscious psychological mechanism that reduces anxiety arising from unacceptable or potentially harmful stimuli.

Defence mechanisms may result in healthy or unhealthy consequences depending on the circumstances and frequency with which the mechanism is used. Defence mechanisms (German: Abwehrmechanismen) are psychological strategies brought into play by the unconscious mind to manipulate, deny, or distort reality in order to defend against feelings of anxiety and unacceptable impulses and to maintain one's self-schema or other schemas. These processes that manipulate, deny, or distort reality may include the following: repression, or the burying of a painful feeling or thought from one's awareness even though it may resurface in a symbolic form; identification, incorporating an object or thought into oneself; and rationalization, the justification of one's behaviour and motivations by substituting "good" acceptable reasons for the actual motivations. In psychoanalytic theory, repression is considered the basis for other defence mechanisms.

Healthy people normally use different defence mechanisms throughout life. A defence mechanism becomes pathological only when its persistent use leads to maladaptive behaviour such that the physical or mental health of the individual is adversely affected. Among the purposes of ego defence mechanisms is to protect the mind/self/ego from anxiety or social sanctions or to provide a refuge from a situation with which one cannot currently cope.

One resource used to evaluate these mechanisms is the Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40).

Theories and classifications

Different

theorists have different categorizations and conceptualizations of

defence mechanisms. Large reviews of theories of defence mechanisms are

available from Paulhus, Fridhandler and Hayes (1997) and Cramer (1991). The Journal of Personality published a special issue on defence mechanisms (1998).

In the first definitive book on defence mechanisms, The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence (1936), Anna Freud enumerated the ten defence mechanisms that appear in the works of her father, Sigmund Freud: repression, regression, reaction formation, isolation, undoing, projection, introjection, turning against one's own person, reversal into the opposite, and sublimation or displacement.

Sigmund Freud posited that defence mechanisms work by distorting id impulses into acceptable forms, or by unconscious or conscious blockage of these impulses.

Anna Freud considered defense mechanisms as intellectual and motor

automatisms of various degrees of complexity, that arose in the process

of involuntary and voluntary learning.

Anna Freud introduced the concept of signal anxiety; she stated

that it was "not directly a conflicted instinctual tension but a signal

occurring in the ego of an anticipated instinctual tension".

The signalling function of anxiety was thus seen as crucial, and

biologically adapted to warn the organism of danger or a threat to its

equilibrium. The anxiety is felt as an increase in bodily or mental

tension, and the signal that the organism receives in this way allows

for the possibility of taking defensive action regarding the perceived

danger.

Both Freuds studied defence mechanisms, but Anna spent more of

her time and research on five main mechanisms: repression, regression,

projection, reaction formation, and sublimation. All defence mechanisms

are responses to anxiety and how the consciousness and unconscious

manage the stress of a social situation.

- Repression: when a feeling is hidden and forced from the consciousness to the unconscious because it is seen as socially unacceptable

- Regression: falling back into an early state of mental/physical development seen as "less demanding and safer"

- Projection: possessing a feeling that is deigned as socially unacceptable and instead of facing it, that feeling or "unconscious urge" is seen in the actions of other people

- Reaction formation: acting the opposite way that the unconscious instructs a person to behave, "often exaggerated and obsessive". For example, if a wife is infatuated with a man who is not her husband, reaction formation may cause her to – rather than cheat – become obsessed with showing her husband signs of love and affection

- Sublimation: seen as the most acceptable of the mechanisms, an expression of anxiety in socially acceptable ways

Otto F. Kernberg (1967) developed a theory of borderline personality organization of which one consequence may be borderline personality disorder. His theory is based on ego psychological object relations theory.

Borderline personality organization develops when the child cannot

integrate helpful and harmful mental objects together. Kernberg views

the use of primitive defence mechanisms as central to this personality

organization. Primitive psychological defences are projection, denial,

dissociation or splitting and they are called borderline defence

mechanisms. Also, devaluation and projective identification are seen as

borderline defences.

In George Eman Vaillant's (1977) categorization, defences form a continuum related to their psychoanalytical developmental level. They are classified into pathological, immature, neurotic and "mature" defences.

Robert Plutchik's (1979) theory views defences as derivatives of basic emotions,

which in turn relate to particular diagnostic structures. According to

his theory, reaction formation relates to joy (and manic features),

denial relates to acceptance (and histrionic features), repression to

fear (and passivity), regression to surprise (and borderline traits),

compensation to sadness (and depression), projection to disgust (and

paranoia), displacement to anger (and hostility) and intellectualization

to anticipation (and obsessionality).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) published by the American Psychiatric Association (1994) includes a tentative diagnostic axis for defence mechanisms.

This classification is largely based on Vaillant's hierarchical view of

defences, but has some modifications. Examples include: denial,

fantasy, rationalization, regression, isolation, projection, and

displacement.

Vaillant's categorization

Psychiatrist George Eman Vaillant introduced a four-level classification of defence mechanisms:

- Level I – pathological defences (psychotic denial, delusional projection)

- Level II – immature defences (fantasy, projection, passive aggression, acting out)

- Level III – neurotic defences (intellectualization, reaction formation, dissociation, displacement, repression)

- Level IV – mature defences (humour, sublimation, suppression, altruism, anticipation)

Level 1: pathological

When predominant, the mechanisms on this level are almost always severely pathological.

These six defences, in conjunction, permit one effectively to

rearrange external experiences to eliminate the need to cope with

reality. Pathological users of these mechanisms frequently appear

irrational or insane to others. These are the "pathological" defences, common in overt psychosis. However, they are normally found in dreams and throughout childhood as well.

They include:

- Delusional projection: Delusions about external reality, usually of a persecutory nature

- Denial: Refusal to accept external reality because it is too threatening; arguing against an anxiety-provoking stimulus by stating it does not exist; resolution of emotional conflict and reduction of anxiety by refusing to perceive or consciously acknowledge the more unpleasant aspects of external reality

- Distortion: A gross reshaping of external reality to meet internal needs

Level 2: immature

These

mechanisms are often present in adults. These mechanisms lessen

distress and anxiety produced by threatening people or by an

uncomfortable reality. Excessive use of such defences is seen as

socially undesirable, in that they are immature, difficult to deal with

and seriously out of touch with reality. These are the so-called

"immature" defences and overuse almost always leads to serious problems

in a person's ability to cope effectively. These defences are often

seen in major depression and personality disorders.

They include:

- Acting out: Direct expression of an unconscious wish or impulse in action, without conscious awareness of the emotion that drives the expressive behavior

- Hypochondriasis: An excessive preoccupation or worry about having a serious illness

- Passive-aggressive behavior: Indirect expression of hostility

- Projection: A primitive form of paranoia. Projection reduces anxiety by allowing the expression of the undesirable impulses or desires without becoming consciously aware of them; attributing one's own unacknowledged, unacceptable, or unwanted thoughts and emotions to another; includes severe prejudice and jealousy, hypervigilance to external danger, and "injustice collecting", all with the aim of shifting one's unacceptable thoughts, feelings and impulses onto someone else, such that those same thoughts, feelings, beliefs and motivations are perceived as being possessed by the other.

- Schizoid fantasy: Tendency to retreat into fantasy in order to resolve inner and outer conflicts

Level 3: neurotic

These mechanisms are considered neurotic,

but fairly common in adults. Such defences have short-term advantages

in coping, but can often cause long-term problems in relationships, work

and in enjoying life when used as one's primary style of coping with

the world.

They include:

- Displacement: Defence mechanism that shifts sexual or aggressive impulses to a more acceptable or less threatening target; redirecting emotion to a safer outlet; separation of emotion from its real object and redirection of the intense emotion toward someone or something that is less offensive or threatening in order to avoid dealing directly with what is frightening or threatening.

- Dissociation: Temporary drastic modification of one's personal identity or character to avoid emotional distress; separation or postponement of a feeling that normally would accompany a situation or thought

- Intellectualization: A form of isolation; concentrating on the intellectual components of a situation so as to distance oneself from the associated anxiety-provoking emotions; separation of emotion from ideas; thinking about wishes in formal, affectively bland terms and not acting on them; avoiding unacceptable emotions by focusing on the intellectual aspects (isolation, rationalization, ritual, undoing, compensation, and magical thinking)

- Reaction formation: Converting unconscious wishes or impulses that are perceived to be dangerous or unacceptable into their opposites; behaviour that is completely the opposite of what one really wants or feels; taking the opposite belief because the true belief causes anxiety

- Repression: The process of attempting to repel desires towards pleasurable instincts, caused by a threat of suffering if the desire is satisfied; the desire is moved to the unconscious in the attempt to prevent it from entering consciousness; seemingly unexplainable naivety, memory lapse or lack of awareness of one's own situation and condition; the emotion is conscious, but the idea behind it is absent.

Level 4: mature

These

are commonly found among emotionally healthy adults and are considered

mature, even though many have their origins in an immature stage of

development. They are conscious processes, adapted through the years in

order to optimise success in human society and relationships. The use of

these defences enhances pleasure and feelings of control. These

defences help to integrate conflicting emotions and thoughts, whilst

still remaining effective. Those who use these mechanisms are usually

considered virtuous.

Mature defences include:

- Altruism: Constructive service to others that brings pleasure and personal satisfaction

- Anticipation: Realistic planning for future discomfort

- Humour: Overt expression of ideas and feelings (especially those that are unpleasant to focus on or too terrible to talk about directly) that gives pleasure to others. The thoughts retain a portion of their innate distress, but they are "skirted around" by witticism, for example, self-deprecation.

- Sublimation: Transformation of unhelpful emotions or instincts into healthy actions, behaviours, or emotions, for example, playing a heavy contact sport such as football or rugby can transform aggression into a game

- Suppression: The conscious decision to delay paying attention to a thought, emotion, or need in order to cope with the present reality; making it possible later to access uncomfortable or distressing emotions whilst accepting them

Other defence mechanisms

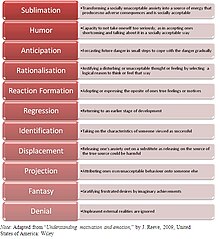

Diagram of selected ego defence mechanisms

Pathological

- Conversion: The expression of an intrapsychic conflict as a physical symptom; examples include blindness, deafness, paralysis, or numbness. This phenomenon is sometimes called hysteria.

- Splitting: A primitive defence. Both harmful and helpful impulses are split off and segregated, frequently projected onto someone else. The defended individual segregates experiences into all-good and all-bad categories, with no room for ambiguity and ambivalence. When "splitting" is combined with "projecting", the undesirable qualities that one unconsciously perceives oneself as possessing, one consciously attributes to another.

Immature

- Idealization: Tending to perceive another individual as having more desirable qualities than he or she may actually have.

- Introjection: Identifying with some idea or object so deeply that it becomes a part of that person. For example, introjection occurs when we take on attributes of other people who seem better able to cope with the situation than we do.

- Passive aggression: Aggression towards others expressed indirectly or passively, often through procrastination.

- Projective identification: The object of projection invokes in that person a version of the thoughts, feelings or behaviours projected.

- Somatization: The transformation of uncomfortable feelings towards others into uncomfortable feelings toward oneself: pain, illness, and anxiety.

- Wishful thinking: Making decisions according to what might be pleasing to imagine instead of by appealing to evidence, rationality, or reality.

Neurotic

- Isolation: Separation of feelings from ideas and events, for example, describing a murder with graphic details with no emotional response.

- Rationalization (making excuses): Convincing oneself that no wrong has been done and that all is or was all right through faulty and false reasoning. An indicator of this defence mechanism can be seen socially as the formulation of convenient excuses.

- Regression: Temporary reversion of the ego to an earlier stage of development rather than handling unacceptable impulses in a more adult way, for example, using whining as a method of communicating despite already having acquired the ability to speak with an appropriate level of maturity.

- Undoing: A person tries to 'undo' an unhealthy, destructive or otherwise threatening thought by acting out the reverse of the unacceptable. Involves symbolically nullifying an unacceptable or guilt provoking thought, idea, or feeling by confession or atonement.

- Upward and downward social comparisons: A defensive tendency that is used as a means of self-evaluation. Individuals will look to another individual or comparison group who are considered to be worse off in order to dissociate themselves from perceived similarities and to make themselves feel better about themselves or their personal situation.

- Withdrawal: Avoidance is a form of defence. It entails removing oneself from events, stimuli, and interactions under the threat of being reminded of painful thoughts and feelings.

Relation with coping

There are many different perspectives on how the construct of defence relates to the construct of coping;

some writers differentiate the constructs in various ways, but "an

important literature exists that does not make any difference between

the two concepts". In at least one of his books, George Eman Vaillant stated that he "will use the terms adaptation, resilience, coping, and defense interchangeably".