Geocentric celestial spheres; Peter Apian's Cosmographia (Antwerp, 1539)

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence),

like jewels set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars

did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued

that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

In modern thought, the orbits of the planets

are viewed as the paths of those planets through mostly empty space.

Ancient and medieval thinkers, however, considered the celestial orbs to

be thick spheres of rarefied matter nested one within the other, each

one in complete contact with the sphere above it and the sphere below. When scholars applied Ptolemy's epicycles, they presumed that each planetary sphere was exactly thick enough to accommodate them.

By combining this nested sphere model with astronomical observations,

scholars calculated what became generally accepted values at the time

for the distances to the Sun (about 4 million miles), to the other

planets, and to the edge of the universe (about 73 million miles). The nested sphere model's distances to the Sun and planets differ significantly from modern measurements of the distances, and the size of the universe is now known to be inconceivably large and continuously expanding.

Albert Van Helden has suggested that from about 1250 until the

17th century, virtually all educated Europeans were familiar with the

Ptolemaic model of "nesting spheres and the cosmic dimensions derived

from it".

Even following the adoption of Copernicus's heliocentric model of the

universe, new versions of the celestial sphere model were introduced,

with the planetary spheres following this sequence from the central Sun:

Mercury, Venus, Earth-Moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

Mainstream belief in the theory of celestial spheres did not survive the Scientific Revolution.

In the early 1600s, Kepler continued to discuss celestial spheres,

although he did not consider that the planets were carried by the

spheres but held that they moved in elliptical paths described by Kepler's laws of planetary motion. In the late 1600s, Greek and medieval theories concerning the motion of terrestrial and celestial objects were replaced by Newton's law of universal gravitation and Newtonian mechanics, which explain how Kepler's laws arise from the gravitational attraction between bodies.

History

Early ideas of spheres and circles

In Greek antiquity the ideas of celestial spheres and rings first appeared in the cosmology of Anaximander in the early 6th century BC.

In his cosmology both the Sun and Moon are circular open vents in

tubular rings of fire enclosed in tubes of condensed air; these rings

constitute the rims of rotating chariot-like wheels pivoting on the

Earth at their centre. The fixed stars are also open vents in such wheel

rims, but there are so many such wheels for the stars that their

contiguous rims all together form a continuous spherical shell

encompassing the Earth. All these wheel rims had originally been formed

out of an original sphere of fire wholly encompassing the Earth, which had disintegrated into many individual rings.

Hence, in Anaximanders's cosmogony, in the beginning was the sphere,

out of which celestial rings were formed, from some of which the stellar

sphere was in turn composed. As viewed from the Earth, the ring of the

Sun was highest, that of the Moon was lower, and the sphere of the stars

was lowest.

Following Anaximander, his pupil Anaximenes

(c. 585–528/4) held that the stars, Sun, Moon, and planets are all made

of fire. But whilst the stars are fastened on a revolving crystal

sphere like nails or studs, the Sun, Moon, and planets, and also the

Earth, all just ride on air like leaves because of their breadth.

And whilst the fixed stars are carried around in a complete circle by

the stellar sphere, the Sun, Moon and planets do not revolve under the

Earth between setting and rising again like the stars do, but rather on

setting they go laterally around the Earth like a cap turning halfway

around the head until they rise again. And unlike Anaximander, he

relegated the fixed stars to the region most distant from the Earth. The

most enduring feature of Anaximenes' cosmos was its conception of the

stars being fixed on a crystal sphere as in a rigid frame, which became a

fundamental principle of cosmology down to Copernicus and Kepler.

After Anaximenes, Pythagoras, Xenophanes and Parmenides all held that the universe was spherical. And much later in the fourth century BC Plato's Timaeus

proposed that the body of the cosmos was made in the most perfect and

uniform shape, that of a sphere containing the fixed stars.

But it posited that the planets were spherical bodies set in rotating

bands or rings rather than wheel rims as in Anaximander's cosmology.

Emergence of the planetary spheres

Instead of bands, Plato's student Eudoxus developed a planetary model using concentric spheres

for all the planets, with three spheres each for his models of the Moon

and the Sun and four each for the models of the other five planets,

thus making 26 spheres in all. Callippus

modified this system, using five spheres for his models of the Sun,

Moon, Mercury, Venus, and Mars and retaining four spheres for the models

of Jupiter and Saturn, thus making 33 spheres in all.

Each planet is attached to the innermost of its own particular set of

spheres. Although the models of Eudoxus and Callippus qualitatively

describe the major features of the motion of the planets, they fail to

account exactly for these motions and therefore cannot provide

quantitative predictions. Although historians of Greek science have traditionally considered these models to be merely geometrical representations, recent studies have proposed that they were also intended to be physically real or have withheld judgment, noting the limited evidence to resolve the question.

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle

developed a physical cosmology of spheres, based on the mathematical

models of Eudoxus. In Aristotle's fully developed celestial model, the

spherical Earth is at the centre of the universe and the planets are

moved by either 47 or 55 interconnected spheres that form a unified

planetary system,

whereas in the models of Eudoxus and Callippus each planet's individual

set of spheres were not connected to those of the next planet.

Aristotle says the exact number of spheres, and hence the number of

movers, is to be determined by astronomical investigation, but he added

additional spheres to those proposed by Eudoxus and Callippus, to

counteract the motion of the outer spheres. Aristotle considers that

these spheres are made of an unchanging fifth element, the aether. Each of these concentric spheres is moved by its own god—an unchanging divine unmoved mover, and who moves its sphere simply by virtue of being loved by it.

Ptolemaic model of the spheres for Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn with epicycle, eccentric deferent and equant point. Georg von Peuerbach, Theoricae novae planetarum, 1474.

In his Almagest, the astronomer Ptolemy

(fl. ca. 150 AD) developed geometrical predictive models of the motions

of the stars and planets and extended them to a unified physical model

of the cosmos in his Planetary hypotheses. By using eccentrics and epicycles,

his geometrical model achieved greater mathematical detail and

predictive accuracy than had been exhibited by earlier concentric

spherical models of the cosmos. In Ptolemy's physical model, each planet is contained in two or more spheres, but in Book 2 of his Planetary Hypotheses Ptolemy depicted thick circular slices rather than spheres as in its Book 1. One sphere/slice is the deferent, with a centre offset somewhat from the Earth; the other sphere/slice is an epicycle embedded in the deferent, with the planet embedded in the epicyclical sphere/slice.

Ptolemy's model of nesting spheres provided the general dimensions of

the cosmos, the greatest distance of Saturn being 19,865 times the

radius of the Earth and the distance of the fixed stars being at least

20,000 Earth radii.

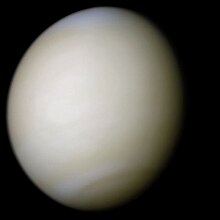

The planetary spheres were arranged outwards from the spherical,

stationary Earth at the centre of the universe in this order: the

spheres of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

In more detailed models the seven planetary spheres contained other

secondary spheres within them. The planetary spheres were followed by

the stellar sphere containing the fixed stars; other scholars added a

ninth sphere to account for the precession of the equinoxes, a tenth to account for the supposed trepidation of the equinoxes, and even an eleventh to account for the changing obliquity of the ecliptic.

In antiquity the order of the lower planets was not universally agreed.

Plato and his followers ordered them Moon, Sun, Mercury, Venus, and

then followed the standard model for the upper spheres.

Others disagreed about the relative place of the spheres of Mercury and

Venus: Ptolemy placed both of them beneath the Sun with Venus above

Mercury, but noted others placed them both above the Sun; some medieval

thinkers, such as al-Bitruji, placed the sphere of Venus above the Sun and that of Mercury below it.

Middle Ages

Astronomical discussions

The Earth within seven celestial spheres, from Bede, De natura rerum, late 11th century

A series of astronomers, beginning with the Muslim astronomer al-Farghānī,

used the Ptolemaic model of nesting spheres to compute distances to the

stars and planetary spheres. Al-Farghānī's distance to the stars was

20,110 Earth radii which, on the assumption that the radius of the Earth

was 3,250 miles, came to 65,357,500 miles. An introduction to Ptolemy's Almagest, the Tashil al-Majisti, believed to be written by Thābit ibn Qurra, presented minor variations of Ptolemy's distances to the celestial spheres. In his Zij, Al-Battānī

presented independent calculations of the distances to the planets on

the model of nesting spheres, which he thought was due to scholars

writing after Ptolemy. His calculations yielded a distance of 19,000

Earth radii to the stars.

Around the turn of the millennium, the Arabic astronomer and polymath Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen)

presented a development of Ptolemy's geocentric epicyclic models in

terms of nested spheres. Despite the similarity of this concept to that

of Ptolemy's Planetary Hypotheses, al-Haytham's presentation

differs in sufficient detail that it has been argued that it reflects an

independent development of the concept. In chapters 15–16 of his Book of Optics, Ibn al-Haytham also said that the celestial spheres do not consist of solid matter.

Near the end of the twelfth century, the Spanish Muslim astronomer al-Bitrūjī (Alpetragius)

sought to explain the complex motions of the planets without Ptolemy's

epicycles and eccentrics, using an Aristotelian framework of purely

concentric spheres that moved with differing speeds from east to west.

This model was much less accurate as a predictive astronomical model, but it was discussed by later European astronomers and philosophers.

In the thirteenth century the astronomer, al-'Urḍi, proposed a radical change to Ptolemy's system of nesting spheres. In his Kitāb al-Hayáh,

he recalculated the distance of the planets using parameters which he

redetermined. Taking the distance of the Sun as 1,266 Earth radii, he

was forced to place the sphere of Venus above the sphere of the Sun; as a

further refinement, he added the planet's diameters to the thickness of

their spheres. As a consequence, his version of the nesting spheres

model had the sphere of the stars at a distance of 140,177 Earth radii.

About the same time, scholars in European universities

began to address the implications of the rediscovered philosophy of

Aristotle and astronomy of Ptolemy. Both astronomical scholars and

popular writers considered the implications of the nested sphere model

for the dimensions of the universe. Campanus of Novara's introductory astronomical text, the Theorica planetarum,

used the model of nesting spheres to compute the distances of the

various planets from the Earth, which he gave as 22,612 Earth radii or

73,387,747 100/660 miles. In his Opus Majus, Roger Bacon

cited Al-Farghānī's distance to the stars of 20,110 Earth radii, or

65,357,700 miles, from which he computed the circumference of the

universe to be 410,818,517 3/7 miles. Clear evidence that this model was thought to represent physical reality is the accounts found in Bacon's Opus Majus of the time needed to walk to the Moon and in the popular Middle English South English Legendary, that it would take 8,000 years to reach the highest starry heaven.

General understanding of the dimensions of the universe derived from

the nested sphere model reached wider audiences through the

presentations in Hebrew by Moses Maimonides, in French by Gossuin of Metz, and in Italian by Dante Alighieri.

Philosophical and theological discussions

Philosophers

were less concerned with such mathematical calculations than with the

nature of the celestial spheres, their relation to revealed accounts of

created nature, and the causes of their motion.

Adi Setia describes the debate among Islamic scholars in the twelfth century, based on the commentary of Fakhr al-Din al-Razi

about whether the celestial spheres are real, concrete physical bodies

or "merely the abstract circles in the heavens traced out… by the

various stars and planets." Setia points out that most of the learned,

and the astronomers, said they were solid spheres "on which the stars

turn… and this view is closer to the apparent sense of the Qur'anic

verses regarding the celestial orbits." However, al-Razi mentions that

some, such as the Islamic scholar Dahhak, considered them to be

abstract. Al-Razi himself, was undecided, he said: "In truth, there is

no way to ascertain the characteristics of the heavens except by

authority [of divine revelation or prophetic traditions]." Setia

concludes: "Thus it seems that for al-Razi (and for others before and

after him), astronomical models, whatever their utility or lack thereof

for ordering the heavens, are not founded on sound rational proofs, and

so no intellectual commitment can be made to them insofar as description

and explanation of celestial realities are concerned."

Christian and Muslim philosophers modified Ptolemy's system to include an unmoved outermost region, the empyrean heaven, which came to be identified as the dwelling place of God and all the elect. Medieval Christians identified the sphere of stars with the Biblical firmament and sometimes posited an invisible layer of water above the firmament, to accord with Genesis. An outer sphere, inhabited by angels, appeared in some accounts.

Edward Grant,

a historian of science, has provided evidence that medieval scholastic

philosophers generally considered the celestial spheres to be solid in

the sense of three-dimensional or continuous, but most did not consider

them solid in the sense of hard. The consensus was that the celestial

spheres were made of some kind of continuous fluid.

Later in the century, the mutakallim Adud al-Din al-Iji (1281–1355) rejected the principle of uniform and circular motion, following the Ash'ari doctrine of atomism, which maintained that all physical effects were caused directly by God's will rather than by natural causes. He maintained that the celestial spheres were "imaginary things" and "more tenuous than a spider's web". His views were challenged by al-Jurjani

(1339–1413), who maintained that even if the celestial spheres "do not

have an external reality, yet they are things that are correctly

imagined and correspond to what [exists] in actuality".

Medieval astronomers and philosophers developed diverse theories

about the causes of the celestial spheres' motions. They attempted to

explain the spheres' motions in terms of the materials of which they

were thought to be made, external movers such as celestial

intelligences, and internal movers such as motive souls or impressed

forces. Most of these models were qualitative, although a few

incorporated quantitative analyses that related speed, motive force and

resistance.

By the end of the Middle Ages, the common opinion in Europe was that

celestial bodies were moved by external intelligences, identified with

the angels of revelation. The outermost moving sphere, which moved with the daily motion affecting all subordinate spheres, was moved by an unmoved mover, the Prime Mover,

who was identified with God. Each of the lower spheres was moved by a

subordinate spiritual mover (a replacement for Aristotle's multiple

divine movers), called an intelligence.

Renaissance

Thomas Digges' 1576 Copernican heliocentric model of the celestial orbs

Early in the sixteenth century Nicolaus Copernicus

drastically reformed the model of astronomy by displacing the Earth

from its central place in favour of the Sun, yet he called his great

work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres).

Although Copernicus does not treat the physical nature of the spheres

in detail, his few allusions make it clear that, like many of his

predecessors, he accepted non-solid celestial spheres.

Copernicus rejected the ninth and tenth spheres, placed the orb of the

Moon around the Earth, and moved the Sun from its orb to the center of

the universe.

The planetary orbs circled the center of the universe in the following

order: Mercury, Venus, the great orb containing the Earth and the orb of

the Moon, then the orbs of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Finally he

retained the eighth sphere of the stars, which he held to be stationary.

The English almanac maker, Thomas Digges, delineated the spheres of the new cosmological system in his Perfit Description of the Caelestiall Orbes …

(1576). Here he arranged the "orbes" in the new Copernican order,

expanding one sphere to carry "the globe of mortalitye", the Earth, the four classical elements,

and the Moon, and expanding the sphere of stars infinitely to encompass

all the stars and also to serve as "the court of the Great God, the

habitacle of the elect, and of the coelestiall angelles."

Johannes Kepler's diagram of the celestial spheres, and of the spaces between them, following the opinion of Copernicus (Mysterium Cosmographicum, 2nd ed., 1621)

In the sixteenth century, a number of philosophers, theologians, and astronomers—among them Francesco Patrizi, Andrea Cisalpino, Peter Ramus, Robert Bellarmine, Giordano Bruno, Jerónimo Muñoz, Michael Neander, Jean Pena, and Christoph Rothmann—abandoned the concept of celestial spheres. Rothmann argued from observations of the comet of 1585 that the lack of observed parallax

indicated that the comet was beyond Saturn, while the absence of

observed refraction indicated the celestial region was of the same

material as air, hence there were no planetary spheres.

Tycho Brahe's investigations of a series of comets from 1577 to 1585, aided by Rothmann's discussion of the comet of 1585 and Michael Maestlin's tabulated distances of the comet of 1577, which passed through the planetary orbs, led Tycho to conclude

that "the structure of the heavens was very fluid and simple." Tycho

opposed his view to that of "very many modern philosophers" who divided

the heavens into "various orbs made of hard and impervious matter."

Edward Grant found relatively few believers in hard celestial spheres

before Copernicus and concluded that the idea first became common

sometime between the publication of Copernicus's De revolutionibus in 1542 and Tycho Brahe's publication of his cometary research in 1588.

In his early Mysterium Cosmographicum, Johannes Kepler

considered the distances of the planets and the consequent gaps

required between the planetary spheres implied by the Copernican system,

which had been noted by his former teacher, Michael Maestlin. Kepler's Platonic cosmology filled the large gaps with the five Platonic polyhedra, which accounted for the spheres' measured astronomical distance.

In Kepler's mature celestial physics, the spheres were regarded as

the purely geometric spatial regions containing each planetary orbit

rather than as the rotating physical orbs of the earlier Aristotelian

celestial physics. The eccentricity of each planet's orbit thereby

defined the radii of the inner and outer limits of its celestial sphere and thus its thickness. In Kepler's celestial mechanics, the cause of planetary motion became the rotating Sun, itself rotated by its own motive soul. However, an immobile stellar sphere was a lasting remnant of physical celestial spheres in Kepler's cosmology.

Literary and visual expressions

"Because the medieval

universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape,

containing within itself an ordered variety....

"The spheres ... present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony."

C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, p. 99"The spheres ... present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony."

Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest Heaven; from Gustave Doré's illustrations to the Divine Comedy, Paradiso Canto 28, lines 16–39

In Cicero's Dream of Scipio, the elder Scipio Africanus

describes an ascent through the celestial spheres, compared to which

the Earth and the Roman Empire dwindle into insignificance. A commentary

on the Dream of Scipio by the Roman writer Macrobius,

which included a discussion of the various schools of thought on the

order of the spheres, did much to spread the idea of the celestial

spheres through the Early Middle Ages.

Nicole Oresme, Le livre du Ciel et du Monde, Paris, BnF, Manuscrits, Fr. 565, f. 69, (1377)

Some late medieval figures noted that the celestial spheres' physical

order was inverse to their order on the spiritual plane, where God was

at the center and the Earth at the periphery. Near the beginning of the

fourteenth century Dante, in the Paradiso of his Divine Comedy, described God as a light at the center of the cosmos. Here the poet ascends beyond physical existence to the Empyrean

Heaven, where he comes face to face with God himself and is granted

understanding of both divine and human nature. Later in the century, the

illuminator of Nicole Oresme's Le livre du Ciel et du Monde, a translation of and commentary on Aristotle's De caelo produced for Oresme's patron, King Charles V,

employed the same motif. He drew the spheres in the conventional order,

with the Moon closest to the Earth and the stars highest, but the

spheres were concave upwards, centered on God, rather than concave

downwards, centered on the Earth. Below this figure Oresme quotes the Psalms that "The heavens declare the Glory of God and the firmament showeth his handiwork."

The late-16th-century Portuguese epic The Lusiads vividly portrays the celestial spheres as a "great machine of the universe" constructed by God.

The explorer Vasco da Gama is shown the celestial spheres in the form

of a mechanical model. Contrary to Cicero's representation, da Gama's

tour of the spheres begins with the Empyrean, then descends inward

toward Earth, culminating in a survey of the domains and divisions of

earthly kingdoms, thus magnifying the importance of human deeds in the

divine plan.