At-will employment is a term used in U.S. labor law for contractual relationships in which an employee can be dismissed by an employer for any reason (that is, without having to establish "just cause" for termination), and without warning,

as long as the reason is not illegal (e.g. firing because of the

employee's race, religion or sexuality). When an employee is

acknowledged as being hired "at will," courts deny the employee any

claim for loss resulting from the dismissal. The rule is justified by

its proponents on the basis that an employee may be similarly entitled

to leave his or her job without reason or warning. The practice is seen as unjust by those who view the employment relationship as characterized by inequality of bargaining power.

At-will employment gradually became the default rule under the common law of the employment contract in most U.S. states during the late 19th century, and was endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court during the Lochner era, when members of the U.S. judiciary consciously sought to prevent government regulation of labor markets. Over the 20th century, many states modified the rule by adding an increasing number of exceptions, or by changing the default expectations in the employment contract altogether. In workplaces with a trade union recognized for purposes of collective bargaining, and in many public sector jobs, the normal standard for dismissal is that the employer must have a "just cause." Otherwise, subject to statutory rights (particularly the discrimination prohibitions under the Civil Rights Act), most states adhere to the general principle that employer and employee may contract for the dismissal protection they choose. At-will employment remains controversial, and remains a central topic of debate in the study of law and economics, especially with regard to the macroeconomic efficiency of allowing employers to summarily and arbitrarily terminate employees.

At-will employment gradually became the default rule under the common law of the employment contract in most U.S. states during the late 19th century, and was endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court during the Lochner era, when members of the U.S. judiciary consciously sought to prevent government regulation of labor markets. Over the 20th century, many states modified the rule by adding an increasing number of exceptions, or by changing the default expectations in the employment contract altogether. In workplaces with a trade union recognized for purposes of collective bargaining, and in many public sector jobs, the normal standard for dismissal is that the employer must have a "just cause." Otherwise, subject to statutory rights (particularly the discrimination prohibitions under the Civil Rights Act), most states adhere to the general principle that employer and employee may contract for the dismissal protection they choose. At-will employment remains controversial, and remains a central topic of debate in the study of law and economics, especially with regard to the macroeconomic efficiency of allowing employers to summarily and arbitrarily terminate employees.

Definition

At-will

employment is generally described as follows: "any hiring is presumed

to be 'at will'; that is, the employer is free to discharge individuals

'for good cause, or bad cause, or no cause at all,' and the employee is

equally free to quit, strike, or otherwise cease work." In an October 2000 decision largely reaffirming employers' rights under the at-will doctrine, the Supreme Court of California explained:

Labor Code section 2922 establishes the presumption that an employer may terminate its employees at will, for any or no reason. A fortiori, the employer may act peremptorily, arbitrarily, or inconsistently, without providing specific protections such as prior warning, fair procedures, objective evaluation, or preferential reassignment. Because the employment relationship is "fundamentally contractual" (Foley, supra, 47 Cal.3d 654, 696), limitations on these employer prerogatives are a matter of the parties' specific agreement, express or implied in fact. The mere existence of an employment relationship affords no expectation, protectible by law, that employment will continue, or will end only on certain conditions, unless the parties have actually adopted such terms. Thus if the employer's termination decisions, however arbitrary, do not breach such a substantive contract provision, they are not precluded by the covenant.

At-will employment disclaimers are a staple of employee handbooks in

the United States. It is common for employers to define what at-will

employment means, explain that an employee's at-will status cannot be

changed except in a writing signed by the company president (or chief

executive), and require that an employee sign an acknowledgment of his

or her at-will status. However, the National Labor Relations Board

has opposed as unlawful the practice of including in such disclaimers

language declaring that the at-will nature of the employment cannot be

changed without the written consent of senior management.

History

The original common law rule for dismissal of employees according to William Blackstone envisaged that, unless another practice was agreed, employees would be deemed to be hired for a fixed term of one year.

Over the 19th century, most states in the North adhered to the rule

that the period by which an employee was paid (a week, a month or a

year) determined the period of notice that should be given before a

dismissal was effective. For instance, in 1870 in Massachusetts, Tatterson v. Suffolk Mfg Co held that an employee's term of hiring dictated the default period of notice.

By contrast, in Tennessee, a court stated in 1884 that an employer

should be allowed to dismiss any worker, or any number of workers, for

any reason at all. An individual, or a collective agreement, according to the general doctrine of freedom of contract

could always stipulate that an employee should only be dismissed for a

good reason, or a "just cause," or that elected employee representatives

would have a say on whether a dismissal should take effect. However,

the position of the typical 19th-century worker meant that this was

rare.

The at-will practice is typically traced to a treatise published by Horace Gray Wood in 1877, called Master and Servant.

Wood cited four U.S. cases as authority for his rule that when a hiring

was indefinite, the burden of proof was on the servant to prove that an

indefinite employment term was for one year. In Toussaint v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Michigan, the Court noted that "Wood's rule was quickly cited as authority for another proposition."

Wood, however, misinterpreted two of the cases which in fact showed

that in Massachusetts and Michigan, at least, the rule was that

employees should have notice before dismissal according to the periods

of their contract.

In New York, the first case to adopt Wood's rule was Martin v New York Life Ins Co

in 1895. Bartlett J asserted that New York law now followed Wood's

treatise, which meant that an employee who received $10,000, paid in a

salary over a year, could be dismissed immediately. The case did not

make reference to the previous authority. Four years earlier, in 1891, Adams v Fitzpatrick

had held that New York law followed the general practice of requiring

notice similar to pay periods. However, subsequent New York cases

continued to follow the at-will rule into the early 20th century.

Some courts saw the rule as requiring the employee to prove an

express contract for a definite term in order to maintain an action

based on termination of the employment. Thus was born the U.S. at-will employment rule, which allowed discharge for no reason. This rule was adopted by all U.S. states. In 1959, the first judicial exception to the at-will rule was created by one of the California Courts of Appeal. Later, in a 1980 landmark case involving ARCO, the Supreme Court of California endorsed the rule first articulated by the Court of Appeal. The resulting civil actions by employees are now known in California as Tameny actions for wrongful termination in violation of public policy.

Since 1959, several common law and statutory exceptions to at-will employment have been created.

Common law protects an employee from retaliation if the employee

disobeys an employer on the grounds that the employer ordered him or her

to do something illegal or immoral. However, in the majority of cases,

the burden of proof remains upon the discharged employee. No U.S. state

but Montana has chosen to statutorily modify the employment at-will rule.

In 1987, the Montana legislature passed the Wrongful Discharge from

Employment Act (WDEA). The WDEA is unique in that, although it purports

to preserve the at-will concept in employment law, it also expressly

enumerates the legal bases for a wrongful discharge action.

Under the WDEA, a discharge is wrongful only if: "it was in retaliation

for the employee's refusal to violate public policy or for reporting a

violation of public policy; the discharge was not for good cause and the

employee had completed the employer's probationary period of employment; or the employer violated the express provisions of its own written personnel policy."

The doctrine of at-will employment can be overridden by an

express contract or civil service statutes (in the case of government

employees). As many as 34% of all U.S. employees apparently enjoy the

protection of some kind of "just cause" or objectively reasonable

requirement for termination that takes them out of the pure "at-will"

category, including the 7.5% of unionized private-sector workers, the

0.8% of nonunion private-sector workers protected by union contracts,

the 15% of nonunion private-sector workers with individual express

contracts that override the at-will doctrine, and the 16% of the total

workforce who enjoy civil service protections as public-sector

employees.

By state

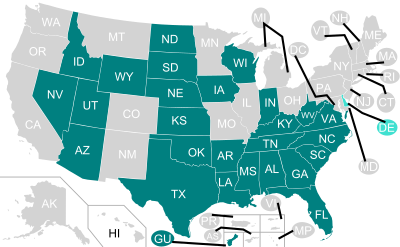

Public policy exceptions

U.S. states (Blue) without a public policy exception

Under the public policy exception, an employer may not fire an employee, if the termination would violate the state's public policy doctrine or a state or federal statute.

This includes retaliating against an employee for performing an

action that complies with public policy (such as repeatedly warning that

the employer is shipping defective airplane parts in violation of

safety regulations promulgated pursuant to the Federal Aviation Act of 1958),

as well as refusing to perform an action that would violate public

policy. In this diagram, the pink states have the 'exception', which

protects the employee.

As of October 2000, 42 U.S. states and the District of Columbia recognize public policy as an exception to the at-will rule.

The 8 states which do not have the exception are:

Implied contract exceptions

U.S. states (pink) with an implied-contract exception

Thirty-six U.S. states (and the District of Columbia) also recognize an implied contract as an exception to at-will employment.

Under the implied contract exception, an employer may not fire an

employee "when an implied contract is formed between an employer and

employee, even though no express, written instrument regarding the

employment relationship exists."

Proving the terms of an implied contract is often difficult, and the

burden of proof is on the fired employee. Implied employment contracts

are most often found when an employer's personnel policies or handbooks

indicate that an employee will not be fired except for good cause or

specify a process for firing. If the employer fires the employee in

violation of an implied employment contract, the employer may be found

liable for breach of contract.

Thirty-six U.S. states have an implied-contract exception. The 14 states having no such exception are:

The implied-contract theory to circumvent at-will employment must be

treated with caution. In 2006, the Texas Court of Civil Appeals in Matagorda County Hospital District v. Burwell

held that a provision in an employee handbook stating that dismissal

may be for cause, and requiring employee records to specify the reason

for termination, did not modify an employee's at-will employment. The

New York Court of Appeals, that state's highest court, also rejected the

implied-contract theory to circumvent employment at will. In Anthony Lobosco, Appellant v. New York Telephone Company/NYNEX, Respondent,

the court restated the prevailing rule that an employee could not

maintain an action for wrongful discharge where state law recognized

neither the tort of wrongful discharge, nor exceptions for firings that

violate public policy, and an employee's explicit employee handbook

disclaimer preserved the at-will employment relationship. And in the

same 2000 decision mentioned above, the Supreme Court of California held

that the length of an employee's long and successful service, standing

alone, is not evidence in and of itself of an implied-in-fact contract

not to terminate except for cause.

"Implied-in-law" contracts

U.S. states (pink) with a covenant-of-good-faith-and-fair-dealing exception

Eleven US states have recognized a breach of an implied covenant of

good faith and fair dealing as an exception to at-will employment. The states are:

Court interpretations of this have varied from requiring "just cause"

to denial of terminations made for malicious reasons, such as

terminating a long-tenured employee solely to avoid the obligation of

paying the employee's accrued retirement benefits. Other court rulings

have denied the exception, holding that it is too burdensome upon the

court for it to have to determine an employer's true motivation for

terminating an employee.

Statutory exceptions

Although all U.S. states have a number of statutory protections for employees, most wrongful termination

suits brought under statutory causes of action use the federal

anti-discrimination statutes which prohibit firing or refusing to hire

an employee because of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age,

or handicap status. Other reasons an employer may not use to fire an

at-will employee are:

- for refusing to commit illegal acts – An employer is not permitted to fire an employee because the employee refuses to commit an act that is illegal.

- family or medical leave – federal law permits most employees to take a leave of absence for specific family or medical problems. An employer is not permitted to fire an employee who takes family or medical leave for a reason outlined in the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993.

- in retaliation against the employee for a protected action taken by the employee – "protected actions" include suing for wrongful termination, testifying as a witness in a wrongful termination case, or even opposing what they believe, whether they can prove it or not, to be wrongful discrimination. In the federal case of Ross v. Vanguard, Raymond Ross successfully sued his employer for firing him due to his allegations of racial discrimination.

Examples of federal statutes include:

- Equal Pay Act of 1963 (relating to discrimination on the basis of sex in payment of wages);

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (relating to discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin);

- Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (relating to certain discrimination on the basis of age with respect to persons of at least 40 years of age);

- Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (related to certain discrimination on the basis of handicap status);

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (relating to certain discrimination on the basis of handicap status).

- The National Labor Relations Act provides protection to employees who wish to join or form a union and those who engage in union activity. The act also protects employees who engage in a "concerted activity." Most employers set forth their workplace rules and policies in an employee handbook. A common provision in those handbooks is a statement that employment with the employer is "at-will." In 2012, the National Labor Relations Board, the federal administrative agency responsible for enforcing the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), instituted two cases attacking at-will employment disclaimers in employee handbooks. The NLRB challenged broadly worded disclaimers, alleging that the statements improperly suggested that employees could not act concertedly to attempt to change the at-will nature of their employment, and thereby interfered with employees' protected rights under the NLRA.

Controversy

The doctrine of at-will employment has been heavily criticized for its severe harshness upon employees.

It has also been criticized as predicated upon flawed assumptions

about the inherent distribution of power and information in the

employee-employer relationship. On the other hand, conservative scholars in the field of law and economics such as Professors Richard A. Epstein and Richard Posner credit employment-at-will as a major factor underlying the strength of the U.S. economy.

At-will employment has also been identified as a reason for the success of Silicon Valley as an entrepreneur-friendly environment.

In a 2009 article surveying the academic literature from both

U.S. and international sources, University of Virginia law professor

J.H. Verkerke explained that "although everyone agrees that raising

firing costs must necessarily deter both discharges and new hiring,

predictions for all other variables depend heavily on the structure of

the model and assumptions about crucial parameters." The effect of raising firing costs is generally accepted in mainstream economics (particularly neoclassical economics); for example, professors Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok explain in their macroeconomics

textbook that employers become more reluctant to hire employees if they

are uncertain about their ability to immediately fire them. However, according to contract theory,

raising firing costs can sometimes be desirable when there are

frictions in the working of markets. For instance, Schmitz (2004) argues

that employment protection laws can be welfare-enhancing when

principal-agent relationships are plagued by asymmetric information.

The first major empirical study on the impact of exceptions to

at-will employment was published in 1992 by James N. Dertouzos and Lynn

A. Karoly of the RAND Corporation,

which found that recognizing tort exceptions to at-will could cause up

to a 2.9% decline in aggregate employment and recognizing contract

exceptions could cause an additional decline of 1.8%. According to

Verkerke, the RAND paper received "considerable attention and

publicity." Indeed, it was favorably cited in a 2010 book published by the libertarian Cato Institute.

However, a 2000 paper by Thomas Miles found no effect upon aggregate employment but found that adopting the implied contract exception causes use of temporary employment to rise as much as 15%. Later work by David Autor

in the mid-2000s identified multiple flaws in Miles' methodology, found

that the implied contract exception decreased aggregate employment 0.8

to 1.6%, and confirmed the outsourcing phenomenon identified by Miles,

but also found that the tort exceptions to at-will had no statistically

significant influence. Autor and colleagues later found in 2007 that the good faith exception does reduce job flows, and seems to cause labor productivity to rise but total factor productivity to drop.

In other words, employers forced to find a "good faith" reason to fire

an employee tend to automate operations to avoid hiring new employees,

but also suffer an impact on total productivity because of the increased

difficulty in discharging unproductive employees.

Other researchers have found that at-will exceptions have a

negative effect on the reemployment of terminated workers who have yet

to find replacement jobs, while their opponents, citing studies that say

"job security has a large negative effect on employment rates," argue

that hedonic regressions on at-will exceptions show large negative effects on individual welfare with regard to home values, rents, and wages