In the context of US labor politics, "right-to-work laws" refers to state laws that prohibit union security agreements between employers and labor unions.

Under these laws, employees in unionized workplaces are banned from

negotiating contracts which require all members who benefit from the

union contract to contribute to the costs of union representation.

According to the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, right-to-work laws prohibit union security agreements, or agreements between employers and labor unions, that govern the extent to which an established union can require employees' membership, payment of union dues, or fees as a condition of employment, either before or after hiring. Right-to-work laws do not aim to provide general guarantee of employment to people seeking work, but rather are a government ban on contractual agreements between employers and union employees requiring workers to pay for the costs of union representation.

Right-to-work laws (either by statutes or by constitutional provision) exist in 27 US states, in the Southern, Midwestern, and interior Western states.[3][4] Such laws are allowed under the 1947 federal Taft–Hartley Act. A further distinction is often made within the law between people employed by state and municipal governments and those employed by the private sector, with states that are otherwise union shop (i.e., workers must pay for union representation in order to obtain or retain a job) having right to work laws in effect for government employees; provided, however, that the law also permits an "agency shop" where employees pay their share for representation (less than union dues), while not joining the union as members.

According to the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, right-to-work laws prohibit union security agreements, or agreements between employers and labor unions, that govern the extent to which an established union can require employees' membership, payment of union dues, or fees as a condition of employment, either before or after hiring. Right-to-work laws do not aim to provide general guarantee of employment to people seeking work, but rather are a government ban on contractual agreements between employers and union employees requiring workers to pay for the costs of union representation.

Right-to-work laws (either by statutes or by constitutional provision) exist in 27 US states, in the Southern, Midwestern, and interior Western states.[3][4] Such laws are allowed under the 1947 federal Taft–Hartley Act. A further distinction is often made within the law between people employed by state and municipal governments and those employed by the private sector, with states that are otherwise union shop (i.e., workers must pay for union representation in order to obtain or retain a job) having right to work laws in effect for government employees; provided, however, that the law also permits an "agency shop" where employees pay their share for representation (less than union dues), while not joining the union as members.

History

Origins

According to Slate,

right-to-work laws are derived from legislation forbidding unions from

forcing strikes on workers, as well as from legal principles such as liberty of contract, which as applied here sought to prevent passage of laws regulating workplace conditions.

According to PandoDaily and NSFWCORP, the term itself was coined by Vance Muse, a Republican

operative who headed an early right-to-work group, the "Christian

American Association", to replace the term "American Plan" after it

became associated with the anti-union violence of the First Red Scare. Muse used racist rhetoric in his defense of "right-to-work" laws.

According to the conservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute, the term "right to work" was coined by Dallas Morning News editorial writer William Ruggles in 1941. (An unrelated use of the term right to work had been coined by French socialist leader Louis Blanc before 1848.)

Wagner Act (1935)

The National Labor Relations Act, generally known as the Wagner Act, was passed in 1935 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Second New Deal". Among other things, the act provided that a company could lawfully agree to be any of the following:

- A closed shop, in which employees must be members of the union as a condition of employment. Under a closed shop, an employee who ceased being a member of the union for whatever reason, from failure to pay dues to expulsion from the union as an internal disciplinary punishment, was required to be fired even if the employee did not violate any of the employer's rules.

- A union shop, which allows for hiring non-union employees, provided that the employees then join the union within a certain period.

- An agency shop, in which employees must pay the equivalent of the cost of union representation, but need not formally join the union.

- An open shop, in which an employee cannot be compelled to join or pay the equivalent of dues to a union or be fired for joining the union.

The act tasked the National Labor Relations Board, which had existed since 1933, with overseeing the rules.

Taft–Hartley Act (1947)

In 1947 Congress passed the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, generally known as the Taft–Hartley Act, over President Harry S. Truman's

veto. The act repealed some parts of the Wagner Act, including

outlawing the closed shop. Section 14(b) of the Taft–Hartley Act also

authorizes individual states (but not local governments,

such as cities or counties) to outlaw the union shop and agency shop

for employees working in their jurisdictions. Any state law that outlaws

such arrangements is known as a right-to-work state.

In the early development of the right-to-work policy,

segregationist sentiment was used as an argument, as many people in the

South felt that it was wrong for blacks and whites to belong to the same

unions. Vance Muse,

one of the early developers of the policy in Texas, used that argument

in the development of anti-union laws in Texas in the 1940s.

Current status

The federal government operates under open shop

rules nationwide, but many of its employees are represented by unions.

Unions that represent professional athletes have written contracts that

include particular representation provisions (such as in the National Football League),

but their application is limited to "wherever and whenever legal," as

the Supreme Court has clearly held that the application of a

right-to-work law is determined by the employee's "predominant job

situs".

Players on professional sports teams in states with right-to-work laws

are thus subject to those laws and cannot be required to pay any portion

of union dues as a condition of continued employment.

Arguments for and against

Rights of dissenting minority and due process

The

first arguments concerning the right to work centered on the rights of a

dissenting minority with respect to an opposing majoritarian collective

bargain. President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal had prompted many US Supreme Court challenges, among which were challenges regarding the constitutionality of the National Industry Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA). In 1936, as a part of its ruling in Carter v. Carter Coal Co. the Court ruled against mandatory collective bargaining, stating:

The effect, in respect to wages and hours, is to subject the dissentient minority ... to the will of the stated majority . ... To 'accept' in these circumstances, is not to exercise a choice, but to surrender to force. The power conferred upon the majority is, in effect, the power to regulate the affairs of an unwilling minority. This is legislative delegation in its most obnoxious form; for it is not even delegation to an official or an official body ... but to private persons . ... [A] statute which attempts to confer such power undertakes an intolerable and unconstitutional interference with personal liberty and private property. The delegation is so clearly arbitrary, and so clearly a denial of rights safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, that it is unnecessary to do more than refer to decisions of this Court which foreclose the question.

Freedom of association

Besides the US Supreme Court, other proponents of right-to-work laws also point to the Constitution and the right to freedom of association.

They argue that workers should both be free to join unions or to

refrain, and thus, sometimes refer to states without right-to-work laws

as forced unionism states. These proponents argue that by being forced

into a collective bargain, what the majoritarian unions call a fair

share of collective bargaining costs is actually financial coercion and a

violation of freedom of choice.

An opponent to the union bargain is forced to financially support an

organization they did not vote for, in order to receive monopoly

representation they have no choice over.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church discourages the joining of unions, citing the writings of Ellen White,

one of the church's founders, and what writer Diana Justice calls the

"loss of free will" that occurs when a person joins a labor union.

Unfairness

Proponents such as the Mackinac Center for Public Policy

contend that it is unfair that unions can require new and existing

employees to either join the union or pay fees for collective bargaining

expenses as a condition of employment under union security agreement contracts.

Other proponents contend that unions may still be needed in new and

growing sectors of the economy, for example, the voluntary and third

party sectors, to assure adequate benefits for new immigrant,

"part-time" aides in America (e.g., US Direct Support Workforce).

Political contributions

Right-to-work proponents, including the Center for Union Facts, contend that political contributions made by unions are not representative of the union workers. The agency shop portion of this had previously been contested with support of National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation in Communications Workers of America v. Beck,

resulting in "Beck rights" preventing agency fees from being used for

expenses outside of collective bargaining if the non-union worker

notifies the union of their objection. The right to challenge the fees must include the right to have it heard by an impartial fact finder. Beck applies only to unions in the private sector, given agency fees were struck down for public-sector unions in Janus v. AFSCME in 2018.

Free riders

Opponents such as Richard Kahlenberg have argued that right-to-work laws simply "gives employees the right to be free riders—to benefit from collective bargaining without paying for it".

Benefits the dissenting union members would receive despite not paying

dues also include representation during arbitration proceedings. In Abood v. Detroit BoE, the Supreme Court of the United States permitted public-sector unions to charge non-members agency fees

so that employees in the public sector could be required to pay for the

costs of representation, even as they opted not to be a member, as long

as these fees are not spent on the union's political or ideological

agenda. This decision was reversed, however, in Janus v. AFSCME,

with the Supreme Court ruling that such fees violate the first

amendment in the case of public-sector unions, since all bargaining by a

public-sector union can be considered political activity.

Freedom of contract and association

Opponents argue that right-to-work laws restrict freedom of association,

and limit the sorts of agreements individuals acting collectively can

make with their employer, by prohibiting workers and employers from

agreeing to contracts that include fair share fees. Moreover, American law imposes a duty of fair representation

on unions; consequently non-members in right to work states can force

unions to provide without compensation grievance services that are paid

for by union members.

In December 2012, libertarian writer J.D. Tuccille, in Reason magazine, wrote: "I consider the restrictions right-to-work laws impose on bargaining between unions and businesses to violate freedom of contract and association.

... I'm disappointed that the state has, once again, inserted itself

into the marketplace to place its thumb on the scale in the never-ending

game of playing business and labor off against one another. ... This is

not to say that unions are always good. It means that, when the state

isn't involved, they're private organizations that can offer value to

their members."

Kahlenberg and Marvit also argue that, at least in efforts to

pass a right-to-work law in Michigan, excluding police and firefighter

unions—traditionally less hostile to Republicans—from the law caused

some to question claims that the law was simply an effort to improve

Michigan's businesses climate, not to seek partisan advantage.

Studies of economic effect

According

to a 2020 study, right-to-work laws lead to greater economic inequality

by indirectly reducing the power of labor unions.

A 2019 paper in the American Economic Review by economists from MIT, Stanford, and the US Census Bureau which surveyed 35,000 US manufacturing plants found that right-to-work laws "boosts incentive management practices."

According to Tim Bartik of the W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research,

studies of the effect of right-to-work laws abound, but are not

consistent. Studies have found both "some positive effect on job

growth," and no effect.

Thomas Holmes argues that it is difficult to analyze right-to-work laws

by comparing states due to other similarities between states that have

passed these laws. For instance, right-to-work states often have some

strong pro-business policies, making it difficult to isolate the effect

of right-to-work laws.

Looking at the growth of states in the Southeast following World War

II, Bartik notes that while they have right-to-work laws they have also

benefited from "factors like the widespread use of air conditioning and

different modes of transportation that helped decentralize

manufacturing".

Economist Thomas Holmes compared counties close to the border

between states with and without right-to-work laws (thereby holding

constant an array of factors related to geography and climate). He found

that the cumulative growth of employment in manufacturing in the

right-to-work states was 26 percentage points greater than that in the

non-right-to-work states.

However, given the study design, Holmes points out "my results do not

say that it is right-to-work laws that matter, but rather that the

'probusiness package' offered by right-to-work states seems to matter." Moreover, as noted by Kevin Drum

and others, this result may reflect business relocation rather than an

overall enhancement of economic growth, since "businesses prefer

locating in states where costs are low and rules are lax."

A February 2011 study by the Economic Policy Institute found:

- Wages in right-to-work states are 3.2 percent lower than those in non-RTW states, after controlling for a full complement of individual demographic and socioeconomic variables as well as state macroeconomic indicators. Using the average wage in non-RTW states as the base ($22.11), the average full-time, full-year worker in an RTW state makes about $1,500 less annually than a similar worker in a non-RTW state. The study goes on to say "How much of this difference can be attributed to RTW status itself? There is an inherent endogeneity problem in any attempt to answer that question, namely that RTW and non-RTW states differ on a wide variety of measures that are also related to compensation, making it difficult to isolate the impact of RTW status."

- The rate of employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) is 2.6 percentage points lower in RTW states compared with non-RTW states, after controlling for individual, job, and state-level characteristics. If workers in non-RTW states were to receive ESI at this lower rate, 2 million fewer workers nationally would be covered.

- The rate of employer-sponsored pensions is 4.8 percentage points lower in RTW states, using the full complement of control variables in [the study's] regression model. If workers in non-RTW states were to receive pensions at this lower rate, 3.8 million fewer workers nationally would have pensions.

A 2008 editorial in The Wall Street Journal comparing job growth in Ohio and Texas

stated that from 1998 to 2008, Ohio lost 10,400 jobs, while Texas

gained 1,615,000. The opinion piece suggested right-to-work laws might

be among the reasons for the economic expansion in Texas, along with the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the absence of a state income tax in Texas. Another Wall Street Journal

editorial in 2012, by the president and the labor policy director of

the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, reported 71 percent employment

growth in right-to-work states from 1980 to 2011, while employment in

non-right-to-work states grew just 32 percent during the same period.

The 2012 editorial also stated that since 2001, compensation in

right-to-work states had increased four times faster than in other

states.

Polling

In January 2012, in the immediate aftermath of passage of Indiana's right-to-work law, a Rasmussen Reports

telephone survey found that 74 percent of likely American voters

disagreed with the question, "Should workers who do not belong to a

union be required by law to pay union dues if the company they work is

unionized?" but "most also don't think a non-union worker should enjoy

benefits negotiated by the union."

In Michigan in January through March 2013, a poll found that 43

percent of those polled thought the law would help Michigan's economy,

while 41 percent thought it would hurt.

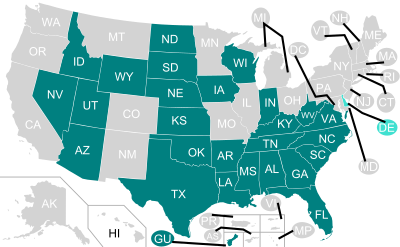

US states with right-to-work laws

Statewide Right-to-work law

Local Right-to-work laws

No Right-to-work law

The following 27 states have right-to-work laws:

- Alabama (adopted 1953, Constitution 2016)

- Arizona (Constitution, adopted 1946)

- Arkansas (Constitution, adopted 1947)

- Florida (Constitution, adopted 1944, revised 1968)

- Georgia (adopted 1947)

- Idaho (adopted 1985)

- Indiana (adopted 2012)

- Iowa (adopted 1947)

- Kansas (Constitution, adopted 1958)

- Kentucky (adopted 2017)

- Louisiana (adopted 1976)

- Michigan (adopted 2012)

- Mississippi (Constitution, adopted 1954)

- Nebraska (Constitution and statute, adopted 1946)

- Nevada (adopted 1951)

- North Carolina (adopted 1947)

- North Dakota (adopted 1947)

- Oklahoma (Constitution, adopted 2001)

- South Carolina (adopted 1954)

- South Dakota (adopted 1946)

- Tennessee (adopted 1947)

- Texas (adopted 1947, revised 1993)

- Utah (adopted 1955)

- Virginia (adopted 1947)

- West Virginia (adopted 2016)

- Wisconsin (adopted 2015)

- Wyoming (adopted 1963)

In addition, the territory of Guam also has right-to-work laws, and employees of the US federal government have the right to choose whether or not to join their respective unions.

Local or repealed laws

Some

states had right-to-work laws in the past, but repealed them or had

them declared invalid. There are also some counties and municipalities

located in states without right-to-work laws that have passed local laws

to ban union security agreements.

Delaware

Seaford passed a right-to-work ordinance in 2018.

Illinois

Lincolnshire passed a local right-to-work ordinance, but it was struck down by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. An appeal to the Supreme Court resulted in the case being vacated as being moot

because in the intervening period Illinois had passed the Illinois

Collective Bargaining Freedom Act to invalidate such local ordinances.

Indiana

Before its passage in 2012, the Republican-controlled Indiana General Assembly

passed a right-to-work bill in 1957, which led to the Democratic

takeover of Indiana's Governor's Mansion and General Assembly in the

coming elections, and eventually, the new Democrat-controlled

legislature repealing the right-to-work law in 1965. Right-to-work was subsequently reenacted in 2012.

Kentucky

On November 18, 2016, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the right of local governments to enact local right-to-work laws in Kentucky. Kentucky had 12 local ordinances. A statewide law was subsequently enacted in 2017.

Missouri

The legislature passed a right-to-work bill in 2017, but the law was defeated in a 2018 referendum before it could take effect.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire adopted a right-to-work bill in 1947, but it was repealed in 1949 by the state legislature and governor.

New Mexico

New Mexico law was previously silent on local right-to-work laws, and Chaves, Eddy, Lea, Lincoln, McKinley, Otero, Roosevelt, Sandoval, San Juan, and Sierra counties, in addition to Ruidoso village adopted such laws. But in 2019 Governor Grisham

signed legislation that prohibits local right-to-work laws and further

states that union membership and the payment of union dues may be

required as a condition of employment in workplaces subject to a

collective bargaining agreement.