From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Kristallnacht (

German pronunciation: [kʁɪsˈtalnaχt] or the

Night of Broken Glass, also called the

November Pogrom(s), was a

pogrom against

Jews carried out by

SA paramilitary forces and civilians throughout

Nazi Germany on 9–10 November 1938. The German authorities looked on without intervening. The name

Kristallnacht

("Crystal Night") comes from the shards of broken glass that littered

the streets after the windows of Jewish-owned stores, buildings and

synagogues were smashed. The pretext for the attacks was the

assassination of the

German diplomat

Ernst vom Rath by

Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old German-born

Polish Jew living in Paris.

Jewish homes, hospitals and schools were ransacked as attackers demolished buildings with sledgehammers. Rioters destroyed 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria and the

Sudetenland. Over 7,000 Jewish businesses were damaged or destroyed, and

30,000 Jewish men were arrested and incarcerated in

concentration camps. British historian

Martin Gilbert

wrote that no event in the history of German Jews between 1933 and 1945

was so widely reported as it was happening, and the accounts from

foreign journalists working in Germany sent shockwaves around the world.

The Times

of London observed on 11 November 1938: "No foreign propagandist bent

upon blackening Germany before the world could outdo the tale of

burnings and beatings, of blackguardly assaults on defenceless and

innocent people, which disgraced that country yesterday."

Estimates of fatalities caused by the attacks have varied. Early reports estimated that 91 Jews had been murdered.

Modern analysis of German scholarly sources puts the figure much

higher; when deaths from post-arrest maltreatment and subsequent

suicides are included, the death toll reaches the hundreds, with

Richard J. Evans estimating 638 deaths by suicide. Historians view

Kristallnacht as a prelude to the

Final Solution and the murder of six million Jews during

the Holocaust.

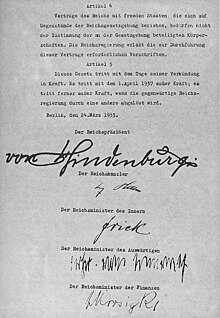

Background

Early Nazi persecutions

In

the 1920s, most German Jews were fully integrated into German society

as German citizens. They served in the German army and navy and

contributed to every field of German

business, science and culture. Conditions for German Jews began to change after the appointment of

Adolf Hitler (the Austrian-born leader of the

National Socialist German Workers' Party) as

Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, and the

Enabling Act (implemented 23 March 1933) which enabled the assumption of power by Hitler after the

Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933. From its inception, Hitler's régime moved quickly to introduce

anti-Jewish policies.

Nazi propaganda

alienated 500,000 Jews in Germany, who accounted for only 0.86% of the

overall population, and framed them as an enemy responsible for

Germany's defeat in the

First World War and for its subsequent economic disasters, such as the

1920s hyperinflation and Wall Street Crash

Great Depression. Beginning in 1933, the German government enacted a series of

anti-Jewish laws restricting the rights of German Jews to earn a living, to enjoy full citizenship and to gain education, including the

Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of 7 April 1933, which forbade Jews to work in the civil service. The subsequent 1935

Nuremberg Laws stripped German Jews of their citizenship and prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jewish Germans.

These laws resulted in the exclusion and alienation of Jews from German social and political life. Many sought asylum abroad; hundreds of thousands emigrated, but as

Chaim Weizmann

wrote in 1936, "The world seemed to be divided into two parts—those

places where the Jews could not live and those where they could not

enter." The international

Évian Conference on 6 July 1938 addressed the issue of Jewish and

Gypsy immigration to other countries. By the time the conference took place, more than 250,000 Jews had fled Germany and

Austria, which had been

annexed by Germany

in March 1938; more than 300,000 German and Austrian Jews continued to

seek refuge and asylum from oppression. As the number of Jews and

Gypsies wanting to leave increased, the restrictions against them grew,

with many countries tightening their rules for admission. By 1938,

Germany "had entered a new radical phase in

anti-Semitic activity".

Some historians believe that the Nazi government had been contemplating

a planned outbreak of violence against the Jews and were waiting for an

appropriate provocation; there is evidence of this planning dating back

to 1937. In a 1997 interview, the German historian

Hans Mommsen claimed that a major motive for the pogrom was the desire of the

Gauleiters of the NSDAP to seize Jewish property and

businesses. Mommsen stated:

The need for money by the party organization stemmed from the fact that Franz Xaver Schwarz,

the party treasurer, kept the local and regional organizations of the

party short of money. In the fall of 1938, the increased pressure on

Jewish property nourished the party's ambition, especially since Hjalmar

Schacht had been ousted as Reich minister for economics. This,

however, was only one aspect of the origin of the November 1938 pogrom.

The Polish government threatened to extradite all Jews who were Polish

citizens but would stay in Germany, thus creating a burden of

responsibility on the German side. The immediate reaction by the Gestapo

was to push the Polish Jews—16,000 persons—over the borderline, but

this measure failed due to the stubbornness of the Polish customs

officers. The loss of prestige as a result of this abortive operation

called for some sort of compensation. Thus, the overreaction to Herschel

Grynszpan's attempt against the diplomat Ernst vom Rath came into being

and led to the November pogrom. The background of the pogrom was

signified by a sharp cleavage of interests between the different

agencies of party and state. While the Nazi party was interested in

improving its financial strength on the regional and local level by

taking over Jewish property, Hermann Göring,

in charge of the Four-Year Plan, hoped to acquire access to foreign

currency in order to pay for the import of urgently-needed raw material.

Heydrich and Himmler were interested in fostering Jewish emigration.

The

Zionist leadership in the

British Mandate of Palestine

wrote in February 1938 that according to "a very reliable private

source—one which can be traced back to the highest echelons of the SS

leadership", there was "an intention to carry out a genuine and dramatic

pogrom in Germany on a large scale in the near future".

Expulsion of Polish Jews in Germany

Polish Jews expelled from Germany in late October 1938

In August 1938, German authorities announced that residence permits

for foreigners were being canceled and would have to be renewed. This included German-born Jews of foreign citizenship.

Poland stated that it would renounce citizenship rights of

Polish Jews living abroad for at least five years after the end of October, effectively making them stateless. In the so-called "

Polenaktion", more than 12,000 Polish Jews, among them the philosopher and theologian Rabbi

Abraham Joshua Heschel, and future literary critic

Marcel Reich-Ranicki

were expelled from Germany on 28 October 1938, on Hitler's orders. They

were ordered to leave their homes in a single night and were allowed

only one suitcase per person to carry their belongings. As the Jews were

taken away, their remaining possessions were seized as loot both by

Nazi authorities and by neighbors.

The deportees were taken from their homes to railway stations and

were put on trains to the Polish border, where Polish border guards

sent them back into Germany. This stalemate continued for days in the

pouring rain, with the Jews marching without food or shelter between the

borders. Four thousand were granted entry into

Poland,

but the remaining 8,000 were forced to stay at the border. They waited

there in harsh conditions to be allowed to enter Poland. A British

newspaper told its readers that hundreds "are reported to be lying

about, penniless and deserted, in little villages along the frontier

near where they had been driven out by the Gestapo and left." Conditions in the

refugee camps

"were so bad that some actually tried to escape back into Germany and

were shot", recalled a British woman who was sent to help those who had

been expelled.

Shooting of vom Rath

Among those expelled was the family of Sendel and Riva Grynszpan,

Polish Jews who had emigrated to Germany in 1911 and settled in

Hanover, Germany. At the trial of

Adolf Eichmann

in 1961, Sendel Grynszpan recounted the events of their deportation

from Hanover on the night of 27 October 1938: "Then they took us in

police trucks, in prisoners' lorries, about 20 men in each truck, and

they took us to the railway station. The streets were full of people

shouting:

'Juden Raus! Auf Nach Palästina!'" ("Jews out, out to Palestine!"). Their seventeen-year-old son

Herschel was living in Paris with an uncle.

Herschel received a postcard from his family from the Polish border,

describing the family's expulsion: "No one told us what was up, but we

realized this was going to be the end ... We haven't a penny. Could you

send us something?" He received the postcard on 3 November 1938.

On the morning of Monday, 7 November 1938, he purchased a

revolver and a box of bullets, then went to the German embassy and asked

to see an embassy official. After he was taken to the office of

Ernst vom Rath,

Grynszpan fired five bullets at Vom Rath, two of which hit him in the

abdomen. Vom Rath was a professional diplomat with the Foreign Office

who expressed anti-Nazi sympathies, largely based on the Nazis'

treatment of the Jews, and was under Gestapo investigation for being

politically unreliable.

Grynszpan made no attempt to escape the French police and freely

confessed to the shooting. In his pocket, he carried a postcard to his

parents with the message, "May God forgive me ... I must protest so that

the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do." It is widely

assumed that the assassination was politically motivated, but historian

Hans-Jürgen Döscher

says the shooting may have been the result of a homosexual love affair

gone wrong. Grynszpan and vom Rath had become intimate after they met in

Le Boeuf sur le Toit, which was a popular meeting place for gay men at the time.

The next day, the German government retaliated, barring Jewish

children from German state elementary schools, indefinitely suspending

Jewish cultural activities, and putting a halt to the publication of

Jewish newspapers and magazines, including the three national German

Jewish newspapers. A newspaper in Britain described the last move, which

cut off the Jewish populace from their leaders, as "intended to disrupt

the Jewish community and rob it of the last frail ties which hold it

together." Their rights as citizens had been stripped.

One of the first legal measures issued was an order by Heinrich

Himmler, commander of all German police, forbidding Jews to possess any

weapons whatsoever and imposing a penalty of twenty years' confinement

in a concentration camp upon every Jew found in possession of a weapon

hereafter.

Pogrom

Death of vom Rath

Telegram sent by Reinhard Heydrich, 10 November 1938

Ernst Vom Rath died of his wounds on 9 November 1938. Word of his

death reached Hitler that evening while he was with several key members

of the Nazi party at a dinner commemorating the 1923

Beer Hall Putsch. After intense discussions, Hitler left the assembly abruptly without giving his usual address. Propaganda Minister

Joseph Goebbels

delivered the speech, in his place, and said that "the Führer has

decided that... demonstrations should not be prepared or organized by

the party, but insofar as they erupt spontaneously, they are not to be

hampered." The chief party judge

Walter Buch later stated that the message was clear; with these words, Goebbels had commanded the party leaders to organize a pogrom.

Some leading party officials disagreed with Goebbels' actions, fearing the diplomatic crisis it would provoke.

Heinrich Himmler

wrote, "I suppose that it is Goebbels's megalomania...and stupidity

which is responsible for starting this operation now, in a particularly

difficult diplomatic situation." The Israeli historian

Saul Friedländer believes that Goebbels had personal reasons for wanting to bring about

Kristallnacht. Goebbels had recently suffered humiliation for the ineffectiveness of his propaganda campaign during the

Sudeten crisis, and was in some disgrace over an affair with a

Czech actress,

Lída Baarová. Goebbels needed a chance to improve his standing in the eyes of Hitler. At 1:20 am on 10 November 1938,

Reinhard Heydrich sent an urgent secret telegram to the

Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police; SiPo) and the

Sturmabteilung

(SA), containing instructions regarding the riots. This included

guidelines for the protection of foreigners and non-Jewish businesses

and property. Police were instructed not to interfere with the riots

unless the guidelines were violated. Police were also instructed to

seize Jewish archives from synagogues and community offices, and to

arrest and detain "healthy male Jews, who are not too old", for eventual

transfer to (labor)

concentration camps.

Riots

Müller, in a message to SA and SS commanders, stated the "most extreme measures" were to be taken against Jewish people. The SA and Hitler Youth shattered the windows of about 7,500 Jewish stores and businesses, hence the appellation

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night), and looted their goods.

Jewish homes were ransacked all throughout Germany. Although violence

against Jews had not been explicitly condoned by the authorities, there

were cases of Jews being beaten or assaulted. Following the violence,

police departments recorded a large number of suicides and rapes.

The rioters destroyed 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Over 1400

synagogues and prayer rooms, many Jewish cemeteries, more than 7,000 Jewish shops, and 29 department stores were damaged, and in many cases destroyed.

More than 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and imprisoned in

Nazi concentration camps; primarily

Dachau,

Buchenwald, and

Sachsenhausen.

The synagogues, some centuries old, were also victims of

considerable violence and vandalism, with the tactics the Stormtroops

practiced on these and other sacred sites described as "approaching the

ghoulish" by the United States Consul in Leipzig. Tombstones were

uprooted and graves violated. Fires were lit, and prayer books, scrolls,

artwork and philosophy texts were thrown upon them, and precious

buildings were either burned or smashed until unrecognizable. Eric Lucas

recalls the destruction of the synagogue that a tiny Jewish community

had constructed in a small village only twelve years earlier:

It did not take long before the

first heavy grey stones came tumbling down, and the children of the

village amused themselves as they flung stones into the many colored

windows. When the first rays of a cold and pale November sun penetrated

the heavy dark clouds, the little synagogue was but a heap of stone,

broken glass and smashed-up woodwork.

After this, the Jewish community was fined 1 billion Reichsmarks

(equivalent to 4 billion 2009 €). In addition, it cost 40 million marks

to repair the windows.

The

Daily Telegraph correspondent,

Hugh Greene, wrote of events in Berlin:

Mob law ruled in Berlin throughout

the afternoon and evening and hordes of hooligans indulged in an orgy of

destruction. I have seen several anti-Jewish outbreaks in Germany

during the last five years, but never anything as nauseating as this.

Racial hatred and hysteria seemed to have taken complete hold of

otherwise decent people. I saw fashionably dressed women clapping their

hands and screaming with glee, while respectable middle-class mothers

held up their babies to see the "fun".

Jews are being forced to walk with the

star of David during the Kristallnacht

Many Berliners were however deeply ashamed of the pogrom, and some

took great personal risks to offer help. The son of a US consular

official heard the janitor of his block cry: "They must have emptied the

insane asylums and penitentiaries to find people who'd do things like

that!"

Tucson News

TV channel briefly reported on a 2008 remembrance meeting at a local

Jewish congregation. According to eyewitness Esther Harris: "They ripped

up the belongings, the books, knocked over furniture, shouted

obscenities". Historian

Gerhard Weinberg is quoted as saying:

Houses of worship burned down, vandalized, in every community in the country where people either participate or watch.

Aftermath

A ruined synagogue in

Munich after

Kristallnacht

A ruined synagogue in

Eisenach after

Kristallnacht

Former German

Kaiser Wilhelm II commented "For the first time, I am ashamed to be German."

Göring, who was in favor of expropriating the Jews rather than

destroying Jewish property as had happened in the pogrom, complained

directly to Sicherheitspolizei Chief Heydrich immediately after

the events: "I'd rather you had done in two-hundred Jews than destroy so

many valuable assets!" ("Mir wäre lieber gewesen, ihr hättet 200 Juden erschlagen und hättet nicht solche Werte vernichtet!").

Göring met with other members of the Nazi leadership on 12 November to

plan the next steps after the riot, setting the stage for formal

government action. In the transcript of the meeting, Göring said,

I have received a letter written on the Führer's

orders requesting that the Jewish question be now, once and for all,

coordinated and solved one way or another... I should not want to leave

any doubt, gentlemen, as to the aim of today's meeting. We have not come

together merely to talk again, but to make decisions, and I implore

competent agencies to take all measures for the elimination of the Jew

from the German economy, and to submit them to me.

The persecution and economic damage inflicted upon German Jews

continued after the pogrom, even as their places of business were

ransacked. They were forced to pay

Judenvermögensabgabe,

a collective fine of one billion marks for the murder of vom Rath

(equal to roughly $US 5.5 billion in today's currency), which was levied

by the compulsory acquisition of 20% of all Jewish property by the

state. Six million Reichsmarks of insurance payments for property damage

due to the Jewish community were to be paid to the government instead

as "damages to the German Nation".

The number of emigrating Jews surged, as those who were able to left the country. In the ten months following

Kristallnacht, more than 115,000 Jews emigrated from the Reich. The majority went to other European countries, the U.S. and

Mandatory Palestine, and at least 14,000 made it to

Shanghai,

China.

As part of government policy, the Nazis seized houses, shops, and other

property the émigrés left behind. Many of the destroyed remains of

Jewish property plundered during Kristallnacht were dumped near

Brandenburg. In October 2008, this dumpsite was discovered by

Yaron Svoray, an investigative journalist. The site, the size of four

Association football

fields, contained an extensive array of personal and ceremonial items

looted during the riots against Jewish property and places of worship on

the night of 9 November 1938. It is believed the goods were brought by

rail to the outskirts of the village and dumped on designated land.

Among the items found were glass bottles engraved with the

Star of David,

mezuzot, painted window sills, and the armrests of chairs found in synagogues, in addition to an ornamental swastika.

Responses to Kristallnacht

From the Germans

The reaction of non-Jewish Germans to

Kristallnacht

was varied. Many spectators gathered on the scenes, most of them in

silence. The local fire departments confined themselves to prevent the

flames from spreading to neighboring buildings. In Berlin, police

Lieutenant Otto Bellgardt barred SA troopers from setting the

New Synagogue on fire, earning his superior officer a verbal reprimand from the commissioner.

Portrait of Paul Ehrlich, damaged on Kristallnacht, then restored by a German neighbor

The British historian

Martin Gilbert believes that "many non-Jews resented the round-up",

his opinion being supported by German witness Dr. Arthur Flehinger who

recalls seeing "people crying while watching from behind their

curtains".

Rolf Dessauers recalls how a neighbor came forward and restored a portrait of

Paul Ehrlich that had been "slashed to ribbons" by the

Sturmabteilung. "He wanted it to be known that not all Germans supported Kristallnacht."

The extent of the damage done on Kristallnacht was so great that many

Germans are said to have expressed their disapproval of it, and to have

described it as senseless.

In an article released for publication on the evening of 11 November, Goebbels ascribed the events of Kristallnacht

to the "healthy instincts" of the German people. He went on to explain:

"The German people are anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its

rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the

Jewish race."

Less than 24 hours after Kristallnacht, Adolf Hitler made a one-hour

long speech in front of a group of journalists where he completely

ignored the recent events on everyone's mind. According to Eugene

Davidson the reason for this was that Hitler wished to avoid being

directly connected to an event that he was aware that many of those

present condemned, regardless of Goebbels's unconvincing explanation

that Kristallnacht was caused by popular wrath.

Goebbels met the foreign press in the afternoon of 11 November and said

that the burning of synagogues and damage to Jewish owned property had

been "spontaneous manifestations of indignation against the murder of

Herr Vom Rath by the young Jew Grynsban [sic]".

In 1938, just after Kristallnacht, the psychologist

Michael Müller-Claudius

interviewed 41 randomly selected Nazi Party members on their attitudes

towards racial persecution. Of the interviewed party-members 63%

expressed extreme indignation against it, while only 5% expressed

approval of racial persecution, the rest being noncommittal.

A study conducted in 1933 had then shown that 33% of Nazi Party members

held no racial prejudice while 13% supported persecution. Sarah Ann

Gordon sees two possible reasons for this difference. First, by 1938

large numbers of Germans had joined the Nazi Party for pragmatic reasons

rather than ideology thus diluting the percentage of rabid antisemites;

second, the Kristallnacht could have caused party members to reject

antisemitism that had been acceptable to them in abstract terms but

which they could not support when they saw it concretely enacted.

During the events of Kristallnacht, several Gauleiter and deputy

Gauleiters had refused orders to enact the Kristallnacht, and many

leaders of the SA and of the Hitler Youth also openly refused party

orders, while expressing disgust. Some Nazis helped Jews during the Kristallnacht.

As it was aware that the German public did not support the

Kristallnacht, the propaganda ministry directed the German press to

portray opponents of racial persecution as disloyal.

The press was also under orders to downplay the Kristallnacht,

describing general events at the local level only, with prohibition

against depictions of individual events. In 1939 this was extended to a prohibition on reporting any anti-Jewish measures.

The U.S. ambassador to Germany reported:

After

1945 some synagogues were restored. This one in Berlin features a

plaque, reading "Never forget", a common expression around Berlin

In view of this being a

totalitarian state a surprising characteristic of the situation here is

the intensity and scope among German citizens of condemnation of the

recent happenings against Jews.

To the consternation of the Nazis, the Kristallnacht affected public

opinion counter to their desires, the peak of opposition against the

Nazi racial policies was reached just then, when according to almost all

accounts the vast majority of Germans rejected the violence perpetrated

against the Jews.

Verbal complaints grew rapidly in numbers, and for example, the

Duesseldorf branch of the Gestapo reported a sharp decline in

anti-Semitic attitudes among the population.

There are many indications of Protestant and Catholic disapproval

of racial persecution; for example, anti-Nazi Protestants adopted the

Barmen Declaration in 1934, and the Catholic church had already distributed

Pastoral letters

critical of Nazi racial ideology, and the Nazi regime expected to

encounter organised resistance from it following Kristallnacht. The Catholic leadership however, just as the various Protestant churches, refrained from responding with organised action. While individual Catholics and Protestants took action, the churches as a whole chose silence publicly. Nevertheless, individuals continued to show courage, for example, a

Parson

paid the medical bills of a Jewish cancer patient and was sentenced to a

large fine and several months in prison in 1941, Reformed Church pastor

Paul Schneider

placed a Nazi sympathizer under church discipline and he was

subsequently sent to Buchenwald where he was murdered. A Catholic nun

was sentenced to death in 1945 for helping Jews. A Protestant parson spoke out in 1943 and was sent to Dachau concentration camp where he died after a few days.

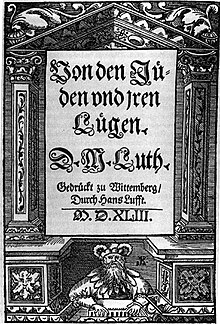

Martin Sasse, Nazi Party member and bishop of the

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Thuringia, leading member of the Nazi

German Christians, one of the schismatic factions of German Protestantism, published a compendium of

Martin Luther's writings shortly after the

Kristallnacht;

Sasse "applauded the burning of the synagogues" and the coincidence of

the day, writing in the introduction, "On 10 November 1938, on Luther's

birthday, the synagogues are burning in Germany." The German people, he

urged, ought to heed these words "of the greatest anti-Semite of his

time, the warner of his people against the Jews."

Diarmaid MacCulloch argued that Luther's 1543 pamphlet,

On the Jews and Their Lies was a "blueprint" for the

Kristallnacht.

British Jews protest against immigration restrictions to Palestine after

Kristallnacht, November 1938

Kristallnacht sparked international outrage. According to

Volker Ullrich, "...a line had been crossed: Germany had left the community of civilised nations." It discredited pro-Nazi movements in

Europe and

North America, leading to an eventual decline in their support. Many newspapers condemned

Kristallnacht, with some of them comparing it to the

murderous pogroms incited by Imperial Russia during the 1880s. The

United States

recalled its ambassador (but it did not break off diplomatic relations)

while other governments severed diplomatic relations with Germany in

protest. The

British government approved the

Kindertransport program for refugee children. As such,

Kristallnacht

also marked a turning point in relations between Nazi Germany and the

rest of the world. The brutality of the pogrom, and the Nazi

government's deliberate policy of encouraging the violence once it had

begun, laid bare the repressive nature and widespread anti-Semitism

entrenched in Germany. World opinion thus turned sharply against the

Nazi regime, with some politicians calling for war. The private protest

against the Germans following

Kristallnacht was held on 6 December 1938.

William Cooper, an Aboriginal Australian, led a delegation of the

Australian Aboriginal League

on a march through Melbourne to the German Consulate to deliver a

petition which condemned the "cruel persecution of the Jewish people by

the Nazi government of Germany". German officials refused to accept the

tendered document.

Kristallnacht as a turning point

Kristallnacht

changed the nature of the Nazi persecution of Jews from economic,

political, and social to physical with beatings, incarceration, and

murder; the event is often referred to as the beginning of

the Holocaust.

In this view, it is described not only as a pogrom but also a critical

stage within a process where each step becomes the seed of the next. An account cited that Hitler's green light for

Kristallnacht was made with the belief that it would help him realize his ambition of getting rid of the Jews in Germany.

Prior to this large-scale and organized violence against the Jews, the

Nazi's primary objective was to eject them from Germany, leaving their

wealth behind. In the words of historian Max Rein in 1988, "Kristallnacht came...and everything was changed."

While November 1938 predated the overt articulation of "the

Final Solution", it foreshadowed the

genocide to come. Around the time of

Kristallnacht, the

SS newspaper

Das Schwarze Korps called for a "destruction by swords and flames." At a conference on the day after the pogrom,

Hermann Göring

said: "The Jewish problem will reach its solution if, in anytime soon,

we will be drawn into war beyond our border—then it is obvious that we

will have to manage a final account with the Jews."

Kristallnacht was also instrumental in changing global

opinion. In the United States, for instance, it was this specific

incident that came to symbolize Nazism and was the reason the Nazis

became associated with evil.

Modern references

Kristallnacht was the inspiration for the 1993 album

Kristallnacht by the composer

John Zorn. The German

power metal band

Masterplan's debut album,

Masterplan (2003), features an anti-Nazi song entitled "Crystal Night" as the fourth track. The German band

BAP published a song titled "Kristallnaach" in their

Cologne dialect, dealing with the emotions engendered by the

Kristallnacht.

Kristallnacht was the inspiration for the 1988 composition

Mayn Yngele by the composer

Frederic Rzewski,

of which he says: "I began writing this piece in November 1988, on the

50th anniversary of the Kristallnacht ... My piece is a reflection on

that vanished part of Jewish tradition which so strongly colors, by its

absence, the culture of our time".

In 2014, the

Wall Street Journal published a letter from billionaire

Thomas Perkins that compared the "progressive war on the American one percent" of wealthiest Americans and the

Occupy movement's "demonization of the rich" to the

Kristallnacht and

anti-semitism in

Nazi Germany. The letter was widely criticized and condemned in

The Atlantic,

The Independent, among bloggers,

Twitter users, and "his own colleagues in

Silicon Valley".

Perkins subsequently apologized for making the comparisons with Nazi

Germany, but otherwise stood by his letter, saying, "In the Nazi era it

was racial demonization, now it's class demonization."

Kristallnacht was invoked as a reference point on 16 July

2018 by a former Watergate Prosecutor, Jill Wine-Banks, during an MSNBC

segment. Her argument was that President Trump's joint press conference

with Russian President Vladimir Putin was a performance that would live

in infamy much like the attack on Pearl Harbor and Kristallnacht.

Kristallnacht has been referenced both explicitly and

implicitly in countless cases of vandalism of Jewish property including

the toppling of gravestones in a Jewish cemetery in suburban St. Louis,

Missouri, and the two 2017 vandalisms of the New England Holocaust Memorial, as the memorial's founder Steve Ross discusses in his book,

From Broken Glass: My Story of Finding Hope in Hitler's Death Camps to Inspire a New Generation. The

Sri Lankan Finance Minister

Mangala Samaraweera also used the term to describe the violence in 2019 against Muslims by Sinhalese nationalists.