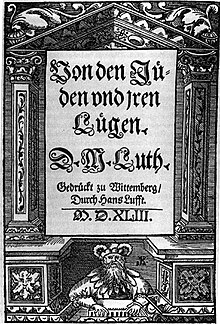

Title page of Martin Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies. Wittenberg, 1543

On the Jews and Their Lies (German: Von den Jüden und iren Lügen; in modern spelling Von den Juden und ihren Lügen) is a 65,000-word anti-Judaic treatise written in 1543 by the German Reformation leader Martin Luther (1483-1546).

Luther's attitude toward the Jews took different forms during his

lifetime. In his earlier period, until 1537 or not much earlier, he

wanted to convert Jews to Lutheranism (Protestant Christianity), but failed. In his later period when he wrote On the Jews and Their Lies, he denounced them and urged their persecution.

In the treatise, he argues that Jewish synagogues and schools be set on fire, their prayer books destroyed, rabbis forbidden to preach, homes burned, and property and money confiscated. They should be shown no mercy or kindness, afforded no legal protection, and "these poisonous envenomed worms" should be drafted into forced labor or expelled for all time. He also seems to advocate their murder, writing "[W]e are at fault in not slaying them".

The book may have had an impact on creating antisemitic Germanic thought through the Middle Ages.

During World War II, copies of the book were held up by Nazis at

rallies, and the prevailing scholarly consensus is that it had a

significant impact on the Holocaust. Since then, the book has been denounced by many Lutheran churches.

Content

In the treatise, Martin Luther describes Jews (in the sense of followers of Judaism) as a "base, whoring people, that is, no people of God, and their boast of lineage, circumcision, and law must be accounted as filth". Luther wrote that they are "full of the devil's feces ... which they wallow in like swine", and the synagogue is an "incorrigible whore and an evil slut".

In the first ten sections of the treatise, Luther expounds, at

considerable length, upon his views concerning Jews and Judaism and how

these compare to Protestants

and Protestant Christianity. Following the exposition, Section XI of

the treatise advises Protestants to carry out seven remedial actions,

namely:

- to burn down Jewish synagogues and schools and warn people against them

- to refuse to let Jews own houses among Christians

- to take away Jewish religious writings

- to forbid rabbis from preaching

- to offer no protection to Jews on highways

- for usury to be prohibited and for all Jews' silver and gold to be removed, put aside for safekeeping, and given back to Jews who truly convert

- to give young, strong Jews flail, axe, spade, and spindle, and let them earn their bread in the sweat of their brow

Luther's essay consistently distinguishes between Jews who accept

Christianity (with whom he has no issues) and Jews who practise Judaism

(whom he excoriates viciously).

In modern terminology, therefore, Luther expresses an anti-Judaic rather than a racist anti-semitic view.

The tract specifically acknowledges that many early Christians, including prominent ones, had a Judaic background.

Evolution of Luther's views

Medieval Church and the Jews

Early in his life, Luther had argued that the Jews had been prevented from converting to Christianity by the proclamation of what he believed to be an impure gospel by the Catholic Church, and he believed they would respond favorably to the evangelical

message if it were presented to them gently. He expressed concern for

the poor conditions in which they were forced to live, and insisted that

anyone denying that Jesus was born a Jew was committing heresy.

Luther's first known comment about the Jews is in a letter written to Reverend Spalatin in 1514:

Conversion of the Jews will be the work of God alone operating from within, and not of man working – or rather playing – from without. If these offences be taken away, worse will follow. For they are thus given over by the wrath of God to reprobation, that they may become incorrigible, as Ecclesiastes says, for every one who is incorrigible is rendered worse rather than better by correction.

In 1519, Luther challenged the doctrine Servitus Judaeorum ("Servitude of the Jews"), established in Corpus Juris Civilis by Justinian I

in 529. He wrote: "Absurd theologians defend hatred for the Jews. ...

What Jew would consent to enter our ranks when he sees the cruelty and

enmity we wreak on them – that in our behavior towards them we less

resemble Christians than beasts?"

In his commentary on the Magnificat, Luther is critical of the emphasis Judaism places on the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament.

He states that they "undertook to keep the law by their own strength,

and failed to learn from it their needy and cursed state". Yet, he concludes that God's grace will continue for Jews as Abraham's descendants for all time, since they may always become Christians. "We ought ... not to treat the Jews in so unkindly a spirit, for there are future Christians among them."

In his 1523 essay That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, Luther

condemned the inhuman treatment of the Jews and urged Christians to

treat them kindly. Luther's fervent desire was that Jews would hear the

gospel proclaimed clearly and be moved to convert to Christianity. Thus

he argued:

If I had been a Jew and had seen such dolts and blockheads govern and teach the Christian faith, I would sooner have become a hog than a Christian. They have dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs rather than human beings; they have done little else than deride them and seize their property. When they baptize them they show them nothing of Christian doctrine or life, but only subject them to popishness and monkery ... If the apostles, who also were Jews, had dealt with us Gentiles as we Gentiles deal with the Jews, there would never have been a Christian among the Gentiles ... When we are inclined to boast of our position [as Christians] we should remember that we are but Gentiles, while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ. We are aliens and in-laws; they are blood relatives, cousins, and brothers of our Lord. Therefore, if one is to boast of flesh and blood the Jews are actually nearer to Christ than we are ... If we really want to help them, we must be guided in our dealings with them not by papal law but by the law of Christian love. We must receive them cordially, and permit them to trade and work with us, that they may have occasion and opportunity to associate with us, hear our Christian teaching, and witness our Christian life. If some of them should prove stiff-necked, what of it? After all, we ourselves are not all good Christians either.

Against the Jews

In August 1536, Luther's prince, John Frederick, Elector of Saxony, issued a mandate that prohibited Jews from inhabiting, engaging in business in, or passing through his realm. An Alsatian shtadlan, Rabbi Josel of Rosheim, asked a reformer, Wolfgang Capito, to approach Luther in order to obtain an audience with the prince, but Luther refused every intercession.

In response to Josel, Luther referred to his unsuccessful attempts to

convert the Jews: "I would willingly do my best for your people but I

will not contribute to your [Jewish] obstinacy by my own kind actions.

You must find another intermediary with my good lord." Heiko Oberman

notes this event as significant in Luther's attitude toward the Jews:

"Even today this refusal is often judged to be the decisive turning

point in Luther's career from friendliness to hostility toward the

Jews";

yet, Oberman contends that Luther would have denied any such "turning

point". Rather he felt that Jews were to be treated in a "friendly way"

in order to avoid placing unnecessary obstacles in their path to

Christian conversion, a genuine concern of Luther.

Paul Johnson

writes that "Luther was not content with verbal abuse. Even before he

wrote his anti-Semitic pamphlet, he got Jews expelled from Saxony in 1537, and in the 1540s he drove them from many German towns; he tried unsuccessfully to get the elector to expel them from Brandenburg in 1543."

Michael Berenbaum writes that Luther's reliance on the Bible as the sole source of Christian authority fed his later fury toward Jews over their rejection of Jesus as the messiah. For Luther, salvation depended on the belief Jesus was Son of God, a belief that adherents of Judaism do not share.

Graham Noble writes that Luther wanted to save Jews, in his own terms,

not exterminate them, but beneath his apparent reasonableness toward

them, there was a "biting intolerance", which produced "ever more

furious demands for their conversion to his own brand of Christianity".

(Noble, 1–2) When they failed to convert, he turned on them.

History since publication

The prevailing scholarly view since the Second World War

is that the treatise exercised a major and persistent influence on

Germany's attitude toward its Jewish citizens in the centuries between

the Reformation and the Holocaust. Four hundred years after it was written, the Nazis displayed On the Jews and Their Lies during Nuremberg rallies, and the city of Nuremberg presented a first edition to Julius Streicher, editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, the newspaper describing it, on Streicher's first encounter with the treatise in 1937, as the most radically antisemitic tract ever published.

Against this view, theologian Johannes Wallmann

writes that the treatise had no continuity of influence in Germany, and

was in fact largely ignored during the 18th and 19th centuries. Hans Hillerbrand argues that to focus on Luther's role in the development of German antisemitism is to underestimate the "larger peculiarities of German history".

Since the 1980s, some Lutheran church

bodies have formally denounced and dissociated themselves from Luther's

vitriol about the Jews. In November 1998, on the 60th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria

issued a statement: "It is imperative for the Lutheran Church, which

knows itself to be indebted to the work and tradition of Martin Luther,

to take seriously also his anti-Jewish utterances, to acknowledge their

theological function, and to reflect on their consequences. It has to

distance itself from every [expression of] anti-Judaism in Lutheran theology."