Semiconductor device fabrication is the process used to manufacture semiconductor devices, typically the metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) devices used in the integrated circuit (IC) chips that are present in everyday electrical and electronic devices. It is a multiple-step sequence of photolithographic and chemical processing steps (such as surface passivation, thermal oxidation, planar diffusion and junction isolation) during which electronic circuits are gradually created on a wafer made of pure semiconducting material. Silicon is almost always used, but various compound semiconductors are used for specialized applications.

The entire manufacturing process, from start to packaged chips ready for shipment, takes six to eight weeks and is performed in highly specialized semiconductor fabrication plants, also called foundries or fabs. All fabrication takes place inside the clean rooms of these fabs. In more advanced semiconductor devices, such as modern 14/10/7 nm nodes, fabrication can take up to 15 weeks, with 11–13 weeks being the industry average. Production in advanced fabrication facilities is completely automated and carried out in a hermetically sealed nitrogen environment to improve yield (the percent of microchips that function correctly in a wafer), with automated material handling systems taking care of the transport of wafers from machine to machine. Wafers are transported inside FOUPs, special sealed plastic boxes. All machinery and FOUPs contains an internal nitrogen atmosphere. The air inside the machinery and FOUPs is usually kept cleaner than the surrounding air in the cleanroom. This internal atmosphere is known as a mini-environment. Fabrication plants need large amounts of liquid nitrogen to maintain the atmosphere inside production machinery and FOUPs, which is constantly purged with nitrogen.

Size

A specific semiconductor process has specific rules on the minimum size and spacing for features on each layer of the chip. Often a newer semiconductor processes allows a simple die shrink to reduce costs and improve performance. Early semiconductor processes had arbitrary names such as HMOS III, CHMOS V; later ones are referred to by size such as 90 nm process.

By industry standard, each generation of the semiconductor manufacturing process, also known as technology node, is designated by the process’ minimum feature size. Technology nodes, also known as "process technologies" or simply "nodes", are typically indicated by the size in nanometers (or historically micrometers) of the process' transistor gate length.

History

20th century

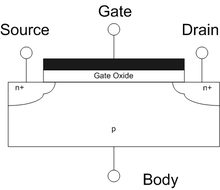

The first metal–oxide–silicon field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) were fabricated by Egyptian engineer Mohamed M. Atalla and Korean engineer Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs between 1959 and 1960. There were originally two types of MOSFET technology, PMOS (p-type MOS) and NMOS (n-type MOS). Both types were developed by Atalla and Kahng when they originally invented the MOSFET, fabricating both PMOS and NMOS devices at 20 µm and 10 µm scales.

An improved type of MOSFET technology, CMOS, was developed by Chih-Tang Sah and Frank Wanlass at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1963. CMOS was commercialised by RCA in the late 1960s. RCA commercially used CMOS for its 4000-series integrated circuits in 1968, starting with a 20 µm process before gradually scaling to a 10 µm process over the next several years.

Semiconductor device manufacturing has since spread from Texas and California in the 1960s to the rest of the world, including Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

21st century

The semiconductor industry is a global business today. The leading semiconductor manufacturers typically have facilities all over the world. Samsung Electronics, the world's largest manufacturer of semiconductors, has facilities in South Korea and the US. Intel, the second-largest manufacturer, has facilities in Europe and Asia as well as the US. TSMC, the world's largest pure play foundry, has facilities in Taiwan, China, Singapore, and the US. Qualcomm and Broadcom are among the biggest fabless semiconductor companies, outsourcing their production to companies like TSMC. They also have facilities spread in different countries.

Since 2009, "node" has become a commercial name for marketing purposes that indicates new generations of process technologies, without any relation to gate length, metal pitch or gate pitch. For example, GlobalFoundries' 7 nm process is similar to Intel's 10 nm process, thus the conventional notion of a process node has become blurred. Additionally, TSMC and Samsung's 10 nm processes are only slightly denser than Intel's 14 nm in transistor density. They are actually much closer to Intel's 14 nm process than they are to Intel's 10 nm process (e.g. Samsung's 10 nm processes' fin pitch is the exact same as that of Intel's 14 nm process: 42 nm).

As of 2019, 14 nanometer and 10 nanometer chips are in mass production by Intel, UMC, TSMC, Samsung, Micron, SK Hynix, Toshiba Memory and GlobalFoundries, with 7 nanometer process chips in mass production by TSMC and Samsung, although their 7 nanometer node definition is similar to Intel's 10 nanometer process. The 5 nanometer process began being produced by Samsung in 2018. As of 2019, the node with the highest transistor density is TSMC's 5 nanometer N5 node, with a density of 171.3 million transistors per square millimeter. In 2019, Samsung and TSMC announced plans to produce 3 nanometer nodes. GlobalFoundries has decided to stop the development of new nodes beyond 12 nanometers in order to save resources, as it has determined that setting up a new fab to handle sub-12nm orders would be beyond the company's financial abilities. As of 2019, Samsung is the industry leader in advanced semiconductor scaling, followed by TSMC and then Intel.

List of steps

This is a list of processing techniques that are employed numerous times throughout the construction of a modern electronic device; this list does not necessarily imply a specific order. Equipment for carrying out these processes is made by a handful of companies. All equipment needs to be tested before a semiconductor fabrication plant is started.

- Wafer processing

- Wet cleans

- Cleaning by solvents such as acetone, trichloroethylene and ultrapure water

- Piranha solution

- RCA clean

- Surface passivation

- Photolithography

- Ion implantation (in which dopants are embedded in the wafer creating regions of increased or decreased conductivity)

- Dry etching

- Atomic layer etching (ALE)

- Wet etching

- Plasma ashing

- Thermal treatments

- Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)

- Atomic layer deposition (ALD)

- Physical vapor deposition (PVD)

- Molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)

- Laser lift-off (for LED production)

- Electrochemical deposition (ECD). See Electroplating

- Chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP)

- Wafer testing (where the electrical performance is verified using Automatic Test Equipment, laser trimming may also be carried out at this step)

- Wet cleans

- Die preparation

- Through-silicon via manufacture (For three-dimensional integrated circuits)

- Wafer mounting (wafer is mounted onto a metal frame using Dicing tape)

- Wafer backgrinding and polishing (reduces the thickness of the wafer for thin devices like a smartcard or PCMCIA card or wafer bonding and stacking, this can also occur during wafer dicing, in a process known as Dice Before Grind or DBG)

- Wafer bonding and stacking (For Three-dimensional integrated circuits and MEMS)

- Redistribution layer manufacture (for WLCSP packages)

- Wafer Bumping (For Flip Chip BGA, and WLCSP packages)

- Die cutting or Wafer dicing

- IC packaging

- Die attachment (The die is attached to the leadframe using conductive paste or die attach film)

- IC bonding: Wire bonding, Thermosonic bonding, Flip chip or Tape Automated Bonding (TAB)

- IC encapsulation

- Molding (using special Molding compound)

- Baking

- Electroplating (plates the copper leads of the lead frames with tin to make soldering easier)

- Laser marking or silkscreen printing

- Trim and form (separates the lead frames from each other, and bends the lead frame's pins so that they can be mounted on a Printed circuit board)

- IC testing

Prevention of contamination and defects

When feature widths were far greater than about 10 micrometres, semiconductor purity was not as big of an issue as it is today in device manufacturing. As devices become more integrated, cleanrooms must become even cleaner. Today, fabrication plants are pressurized with filtered air to remove even the smallest particles, which could come to rest on the wafers and contribute to defects. The workers in a semiconductor fabrication facility are required to wear cleanroom suits to protect the devices from human contamination. To prevent oxidation and to increase yield, FOUPs and semiconductor capital equipment may have a hermetically sealed pure nitrogen environment with ISO class 1 level of dust.

Wafers

A typical wafer is made out of extremely pure silicon that is grown into mono-crystalline cylindrical ingots (boules) up to 300 mm (slightly less than 12 inches) in diameter using the Czochralski process. These ingots are then sliced into wafers about 0.75 mm thick and polished to obtain a very regular and flat surface.

Processing

In semiconductor device fabrication, the various processing steps fall into four general categories: deposition, removal, patterning, and modification of electrical properties.

- Deposition is any process that grows, coats, or otherwise transfers a material onto the wafer. Available technologies include physical vapor deposition (PVD), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), electrochemical deposition (ECD), molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) and more recently, atomic layer deposition (ALD) among others. Deposition can be understood to include oxide layer formation, by thermal oxidation or, more specifically, LOCOS.

- Removal is any process that removes material from the wafer; examples include etch processes (either wet or dry) and chemical-mechanical planarization (CMP).

- Patterning is the shaping or altering of deposited materials, and is generally referred to as lithography. For example, in conventional lithography, the wafer is coated with a chemical called a photoresist; then, a machine called a stepper focuses, aligns, and moves a mask, exposing select portions of the wafer below to short-wavelength light; the exposed regions are washed away by a developer solution. After etching or other processing, the remaining photoresist is removed by plasma ashing.

- Modification of electrical properties has historically entailed doping transistor sources and drains (originally by diffusion furnaces and later by ion implantation). These doping processes are followed by furnace annealing or, in advanced devices, by rapid thermal annealing (RTA); annealing serves to activate the implanted dopants. Modification of electrical properties now also extends to the reduction of a material's dielectric constant in low-k insulators via exposure to ultraviolet light in UV processing (UVP). Modification is frequently achieved by oxidation, which can be carried out to create semiconductor-insulator junctions, such as in the local oxidation of silicon (LOCOS) to fabricate metal oxide field effect transistors.

Modern chips have up to eleven metal levels produced in over 300 sequenced processing steps.

Front-end-of-line (FEOL) processing

FEOL processing refers to the formation of the transistors directly in the silicon. The raw wafer is engineered by the growth of an ultrapure, virtually defect-free silicon layer through epitaxy. In the most advanced logic devices, prior to the silicon epitaxy step, tricks are performed to improve the performance of the transistors to be built. One method involves introducing a straining step wherein a silicon variant such as silicon-germanium (SiGe) is deposited. Once the epitaxial silicon is deposited, the crystal lattice becomes stretched somewhat, resulting in improved electronic mobility. Another method, called silicon on insulator technology involves the insertion of an insulating layer between the raw silicon wafer and the thin layer of subsequent silicon epitaxy. This method results in the creation of transistors with reduced parasitic effects.

Gate oxide and implants

Front-end surface engineering is followed by growth of the gate dielectric (traditionally silicon dioxide), patterning of the gate, patterning of the source and drain regions, and subsequent implantation or diffusion of dopants to obtain the desired complementary electrical properties. In dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) devices, storage capacitors are also fabricated at this time, typically stacked above the access transistor (the now defunct DRAM manufacturer Qimonda implemented these capacitors with trenches etched deep into the silicon surface).

Back-end-of-line (BEOL) processing

Metal layers

Once the various semiconductor devices have been created, they must be interconnected to form the desired electrical circuits. This occurs in a series of wafer processing steps collectively referred to as BEOL (not to be confused with back end of chip fabrication, which refers to the packaging and testing stages). BEOL processing involves creating metal interconnecting wires that are isolated by dielectric layers. The insulating material has traditionally been a form of SiO2 or a silicate glass, but recently new low dielectric constant materials are being used (such as silicon oxycarbide), typically providing dielectric constants around 2.7 (compared to 3.82 for SiO2), although materials with constants as low as 2.2 are being offered to chipmakers.

Interconnect

Historically, the metal wires have been composed of aluminum. In this approach to wiring (often called subtractive aluminum), blanket films of aluminum are deposited first, patterned, and then etched, leaving isolated wires. Dielectric material is then deposited over the exposed wires. The various metal layers are interconnected by etching holes (called "vias") in the insulating material and then depositing tungsten in them with a CVD technique; this approach is still used in the fabrication of many memory chips such as dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), because the number of interconnect levels is small (currently no more than four).

More recently, as the number of interconnect levels for logic has substantially increased due to the large number of transistors that are now interconnected in a modern microprocessor, the timing delay in the wiring has become so significant as to prompt a change in wiring material (from aluminum to copper interconnect layer) and a change in dielectric material (from silicon dioxides to newer low-K insulators). This performance enhancement also comes at a reduced cost via damascene processing, which eliminates processing steps. As the number of interconnect levels increases, planarization of the previous layers is required to ensure a flat surface prior to subsequent lithography. Without it, the levels would become increasingly crooked, extending outside the depth of focus of available lithography, and thus interfering with the ability to pattern. CMP (chemical-mechanical planarization) is the primary processing method to achieve such planarization, although dry etch back is still sometimes employed when the number of interconnect levels is no more than three.

Wafer test

The highly serialized nature of wafer processing has increased the demand for metrology in between the various processing steps. For example, thin film metrology based on ellipsometry or reflectometry is used to tightly control the thickness of gate oxide, as well as the thickness, refractive index and extinction coefficient of photoresist and other coatings. Wafer test metrology equipment is used to verify that the wafers haven't been damaged by previous processing steps up until testing; if too many dies on one wafer have failed, the entire wafer is scrapped to avoid the costs of further processing. Virtual metrology has been used to predict wafer properties based on statistical methods without performing the physical measurement itself.

Device test

Once the front-end process has been completed, the semiconductor devices are subjected to a variety of electrical tests to determine if they function properly. The percent of devices on the wafer found to perform properly is referred to as the yield. Manufacturers are typically secretive about their yields, but it can be as low as 30%, meaning that only 30% of the chips on the wafer work as intended. Process variation is one among many reasons for low yield.

The number of defects is often but not necessarily proportional to device (die) size. As an example, In December 2019, TSMC announced an average yield of ~80%, with a peak yield per wafer of >90% for their 5nm test chips with a die size of 17.92 mm2. The yield went down to 32.0% with an increase in die size to 100 mm2.

The fab tests the chips on the wafer with an electronic tester that presses tiny probes against the chip. The machine marks each bad chip with a drop of dye. Currently, electronic dye marking is possible if wafer test data (results) are logged into a central computer database and chips are "binned" (i.e. sorted into virtual bins) according to predetermined test limits such as maximum operating frequencies/clocks, number of working (fully functional) cores per chip, etc. The resulting binning data can be graphed, or logged, on a wafer map to trace manufacturing defects and mark bad chips. This map can also be used during wafer assembly and packaging. Binning allows chips that would otherwise be rejected to be reused in lower-tier products, as is the case with GPUs and CPUs, increasing device yield, specially since very few chips are fully functional (have all cores functioning correctly, for example). eFUSEs may be used to disconnect parts of chips such as cores, either because they didn't work as intended during binning, or as part of market segmentation (using the same chip for low, mid and high-end tiers). Chips may have spare parts to allow the chip to fully pass testing even if it has several non-working parts.

Chips are also tested again after packaging, as the bond wires may be missing, or analog performance may be altered by the package. This is referred to as the "final test". Chips may also be imaged using x-rays.

Usually, the fab charges for testing time, with prices in the order of cents per second. Testing times vary from a few milliseconds to a couple of seconds, and the test software is optimized for reduced testing time. Multiple chip (multi-site) testing is also possible because many testers have the resources to perform most or all of the tests in parallel.

Chips are often designed with "testability features" such as scan chains or a "built-in self-test" to speed testing and reduce testing costs. In certain designs that use specialized analog fab processes, wafers are also laser-trimmed during testing, in order to achieve tightly-distributed resistance values as specified by the design.

Good designs try to test and statistically manage corners (extremes of silicon behavior caused by a high operating temperature combined with the extremes of fab processing steps). Most designs cope with at least 64 corners.

Die preparation

Once tested, a wafer is typically reduced in thickness in a process also known as "backlap", "backfinish" or "wafer thinning" before the wafer is scored and then broken into individual dies, a process known as wafer dicing. Only the good, unmarked chips are packaged.

Packaging

Plastic or ceramic packaging involves mounting the die, connecting the die pads to the pins on the package, and sealing the die. Tiny bondwires are used to connect the pads to the pins. In the old days, wires were attached by hand, but now specialized machines perform the task. Traditionally, these wires have been composed of gold, leading to a lead frame (pronounced "leed frame") of solder-plated copper; lead is poisonous, so lead-free "lead frames" are now mandated by RoHS.

Chip scale package (CSP) is another packaging technology. A plastic dual in-line package, like most packages, is many times larger than the actual die hidden inside, whereas CSP chips are nearly the size of the die; a CSP can be constructed for each die before the wafer is diced.

The packaged chips are retested to ensure that they were not damaged during packaging and that the die-to-pin interconnect operation was performed correctly. A laser then etches the chip's name and numbers on the package.

Hazardous materials

Many toxic materials are used in the fabrication process. These include:

- poisonous elemental dopants, such as arsenic, antimony, and phosphorus.

- poisonous compounds, such as arsine, phosphine, and silane.

- highly reactive liquids, such as hydrogen peroxide, fuming nitric acid, sulfuric acid, and hydrofluoric acid.

It is vital that workers should not be directly exposed to these dangerous substances. The high degree of automation common in the IC fabrication industry helps to reduce the risks of exposure. Most fabrication facilities employ exhaust management systems, such as wet scrubbers, combustors, heated absorber cartridges, etc., to control the risk to workers and to the environment.