| Gulf of Tonkin incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

Photo taken from USS Maddox during the incident, showing three North Vietnamese motor torpedo boats. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

George S. Morrison John J. Herrick Roy L. Johnson | Le Duy Khoai | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Sea: 1 aircraft carrier, 1 destroyer Air: 4 aircraft | 3 torpedo boats | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 destroyer slightly damaged, 1 aircraft slightly damaged |

1 torpedo boat severely damaged, 2 torpedo boats moderately damaged, 4 killed, 6 wounded | ||||||

The Gulf of Tonkin incident (Vietnamese: Sự kiện Vịnh Bắc Bộ), also known as the USS Maddox incident, was a disputed international confrontation that led to the United States engaging more directly in the Vietnam War. It involved both a real confrontation and a fabricated confrontation between ships of North Vietnam and the United States in the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin. The original American report blamed North Vietnam for both incidents.

On Sunday, August 2, 1964, the destroyer USS Maddox, while performing a signals intelligence patrol as part of DESOTO operations, was falsely claimed to have been approached by three North Vietnamese Navy torpedo boats of the 135th Torpedo Squadron. Maddox fired three warning shots, and it was claimed the North Vietnamese boats attacked with torpedoes and machine gun fire. Maddox expended over 280 3-inch (76 mm) and 5-inch (130 mm) shells in a sea battle. According to the false report: One U.S. aircraft was damaged, three North Vietnamese torpedo boats were damaged, and four North Vietnamese sailors were killed, with six more wounded. There were no U.S. casualties. Maddox was "unscathed except for a single bullet hole from a Vietnamese machine gun round".

It was originally claimed by the National Security Agency that a Second Gulf of Tonkin incident occurred on August 4, 1964, as another sea battle, but instead, evidence was found of "Tonkin ghosts" (false radar images) and not actual North Vietnamese torpedo boats. In the 2003 documentary The Fog of War, the former United States Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara admitted that the August 2 USS Maddox attack happened with no Defense Department response, but the August 4 Gulf of Tonkin attack never happened. In 1995, McNamara met with former Vietnam People's Army General Võ Nguyên Giáp to ask what happened on August 4, 1964, in the second Gulf of Tonkin Incident. "Absolutely nothing", Giáp replied. Giáp claimed that the attack had been imaginary.

The outcome of these two incidents was the passage by US Congress of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted US President Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to assist any Southeast Asian country whose government was considered to be jeopardized by "communist aggression". The resolution served as Johnson's legal justification for deploying U.S. conventional forces and the commencement of open warfare against North Vietnam.

In 2005, an internal National Security Agency historical study was declassified; it concluded that Maddox had engaged the North Vietnamese Navy on August 2, but that there were no North Vietnamese naval vessels present during the incident of August 4. The report stated, regarding the first incident on August 2:

at 1500G, Captain Herrick ordered Ogier's gun crews to open fire if the boats approached within ten thousand yards (9,150 m). At about 1505G, Maddox fired three rounds to warn off the communist [North Vietnamese] boats. This initial action was never reported by the Johnson administration, which insisted that the Vietnamese boats fired first.

Background

Although the United States attended the Geneva Conference (1954), which was intended to end hostilities between France and the Vietnamese at the end of the First Indochina War, it refused to sign the Geneva Accords (1954). The accords mandated, among other measures, a temporary ceasefire line, intended to separate Vietnamese and French forces, and elections to determine the future political fate of the Vietnamese within two years. It also forbade the political interference of other countries in the area, the creation of new governments without the stipulated elections, and foreign military presence. By 1961, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem faced significant discontent among some quarters of the southern population, including some Buddhists who were opposed to the rule of Diem's Catholic supporters. After suppressing Vietminh political cadres who were legally campaigning between 1955 and 1959 for the promised elections, Diem faced a growing communist-led uprising that intensified by 1961, headed by the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong).

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident occurred during the first year of the Johnson administration. While US President John F. Kennedy had originally supported the policy of sending military advisers to Diem, he had begun to alter his thinking due to what he perceived to be the ineptitude of the Saigon government and its inability and unwillingness to make needed reforms (which led to a U.S.-supported coup which resulted in the death of Diem). Shortly before Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, he had begun a limited recall of U.S. forces. Johnson's views were likewise complex, but he had supported military escalation as a means of challenging what was perceived to be the Soviet Union's expansionist policies. The Cold War policy of containment was to be applied to prevent the fall of Southeast Asia to communism under the precepts of the domino theory. After Kennedy's assassination, Johnson ordered in more U.S. forces to support the Saigon government, beginning a protracted United States presence in Southeast Asia.

A highly classified program of covert actions against North Vietnam, known as Operation Plan 34-Alpha, in conjunction with the DESOTO operations, had begun under the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1961. In 1964 the program was transferred to the Defense Department and conducted by the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG).

For the maritime portion of the covert operation, a set of fast patrol boats had been purchased quietly from Norway and sent to South Vietnam. In 1963 three young Norwegian skippers traveled on a mission in South Vietnam. They were recruited for the job by the Norwegian intelligence officer Alf Martens Meyer. Martens Meyer, who was head of department at the military intelligence staff, operated on behalf of U.S. intelligence. The three skippers did not know who Meyer really was when they agreed to a job that involved them in sabotage missions against North Vietnam. Although the boats were crewed by South Vietnamese naval personnel, approval for each mission conducted under the plan came directly from Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, Jr., CINCPAC in Honolulu, who received his orders from the White House. After the coastal attacks began, Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam, lodged a complaint with the International Control Commission (ICC), which had been established in 1954 to oversee the terms of the Geneva Accords, but the U.S. denied any involvement. Four years later, Secretary McNamara admitted to Congress that the U.S. ships had in fact been cooperating in the South Vietnamese attacks against North Vietnam. Maddox, although aware of the operations, was not directly involved.

What was generally not considered by U.S. politicians at the time were the other actions taken under Operations Plan 34-Alpha just prior to the incident. The night before the launching of the actions against North Vietnamese facilities on Hòn Mê and Hòn Ngư islands, the SOG had launched a covert long-term agent team into North Vietnam, which was promptly captured. That night (for the second evening in a row), two flights of CIA-sponsored Laotian fighter-bombers (piloted by Thai mercenaries) attacked border outposts well within southwestern North Vietnam. The Hanoi government (which, unlike the U.S. government, had to give permission at the highest levels for the conduct of such missions) probably assumed that they were all a coordinated effort to escalate military actions against North Vietnam.

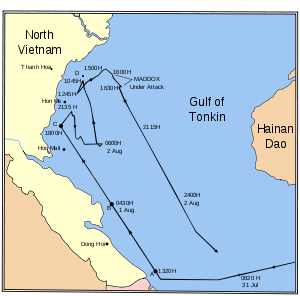

Incident

Daniel Ellsberg, who was on duty in the Pentagon the night of August 4, receiving messages from the ship, reported that the ship was on a secret electronic warfare support measures mission (codenamed "DESOTO") near Northern Vietnamese territorial waters. On July 31, 1964, USS Maddox had begun her intelligence collection mission in the Gulf of Tonkin. Captain George Stephen Morrison was in command of local American forces from his flagship USS Bon Homme Richard. Maddox was under orders not to approach closer than eight miles (13 km) from the North's coast and four miles (6 km) from Hon Nieu island. When the SOG commando raid was being carried out against Hon Nieu, the ship was 120 miles (190 km) away from the attacked area.

First attack

In July 1964, "the situation along North Vietnam's territorial waters had reached a near boil", due to South Vietnamese commando raids and airborne operations that inserted intelligence teams into North Vietnam, as well as North Vietnam's military response to these operations. On the night of July 30, 1964, South Vietnamese commandos attacked a North Vietnamese radar station on Hòn Mê island. According to Hanyok, "it would be attacks on these islands, especially Hòn Mê, by South Vietnamese commandos, along with the proximity of the Maddox, that would set off the confrontation", although the Maddox did not participate in the commando attacks. In this context, on July 31, Maddox began patrols of the North Vietnamese coast to collect intelligence, coming within a few miles of Hòn Mê island. A U.S. aircraft carrier, the USS Ticonderoga, was also stationed nearby.

By August 1, North Vietnamese patrol boats were tracking Maddox, and several intercepted communications indicated that they were preparing to attack. Maddox retreated, but the next day, August 2, Maddox, which had a top speed of 28 knots, resumed her routine patrol, and three North Vietnamese P-4 torpedo boats with a top speed of 50 knots began to follow Maddox. Intercepted communications indicated that the vessels intended to attack Maddox. As the ships approached from the southwest, Maddox changed course from northeasterly to southeasterly and increased speed to 25 knots. On the afternoon of August 2, as the torpedo boats neared, Maddox fired three warning shots. The North Vietnamese boats then attacked and Maddox radioed she was under attack from the three boats, closing to within 10 nautical miles (19 km; 12 mi), while located 28 nautical miles (52 km; 32 mi) away from the North Vietnamese coast in international waters. Maddox stated she had evaded a torpedo attack and opened fire with its five-inch (127 mm) guns, forcing the torpedo boats away. Two of the torpedo boats had come as close as 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi) and released one torpedo each, but neither one was effective, coming no closer than about 100 yards (91 m) after Maddox evaded them. Another P-4 received a direct hit from a five-inch shell from Maddox; its torpedo malfunctioned at launch. Four USN F-8 Crusader jets launched from the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga and 15 minutes after Maddox had fired her initial warning shots, attacked the retiring P-4s, claiming one was sunk and one heavily damaged. Maddox suffered only minor damage from a single 14.5 mm bullet from a P-4's KPV heavy machine gun into her superstructure. Retiring to South Vietnamese waters, Maddox was joined by the destroyer USS Turner Joy. The North Vietnamese claimed that Maddox was hit by one torpedo, and one of the American aircraft had been shot down.

The original account from the Pentagon Papers has been revised in light of a 2005 internal NSA historical study, which stated on page 17:

At 1500G, Captain Herrick (commander of Maddox) ordered Ogier's gun crews to open fire if the boats approached within ten thousand yards. At about 1505G, Maddox fired three rounds to warn off the communist [North Vietnamese] boats. This initial action was never reported by the Johnson administration, which insisted that the Vietnamese boats fired first.

Maddox, when confronted, was approaching Hòn Mê Island, three to four nautical miles (nmi) (6 to 7 km) inside the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) limit claimed by North Vietnam. This territorial limit was unrecognized by the United States. After the skirmish, Johnson ordered Maddox and Turner Joy to stage daylight runs into North Vietnamese waters, testing the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) limit and North Vietnamese resolve. These runs into North Vietnamese territorial waters coincided with South Vietnamese coastal raids and were interpreted as coordinated operations by the North, which officially acknowledged the engagements of August 2, 1964.

Others, such as Admiral Sharp, maintained that U.S. actions did not provoke the August 2 incident. He claimed that the North Vietnamese had tracked Maddox along the coast by radar, and were thus aware that the destroyer had not actually attacked North Vietnam and that Hanoi (or the local commander) had ordered its craft to engage Maddox anyway. North Vietnamese general Phùng Thế Tài later claimed that Maddox had been tracked since July 31 and that she had attacked fishing boats on August 2 forcing the North Vietnamese Navy to "fight back".

Sharp also noted that orders given to Maddox to stay 8 nautical miles (15 km; 9.2 mi) off the North Vietnamese coast put the ship in international waters, as North Vietnam claimed only a 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi) limit as its territory (or off of its off-shore islands). In addition, many nations had previously carried out similar missions all over the world, and the destroyer USS John R. Craig had earlier conducted an intelligence-gathering mission in similar circumstances without incident.

However Sharp's claims include some factually incorrect statements. North Vietnam never claimed an 8-kilometer (5 mi) limit for its territorial waters, instead it adhered to a 20-kilometer (12 mi) limit claimed by French Indochina in 1936. Moreover it officially claimed a 12 nmi limit, which is practically identical to the old 20 km French claim, after the incidents of August, in September 1964. The North Vietnamese stance is that they always considered a 12 nautical mile limit, consistently with the positions regarding the law of the sea of both the Soviet Union and China, their main allies.

Second alleged attack

On August 4, another DESOTO patrol off the North Vietnamese coast was launched by Maddox and Turner Joy, in order to "show the flag" after the first incident. This time their orders indicated that the ships were to close to no less than 11 miles (18 km) from the coast of North Vietnam. During an evening and early morning of rough weather and heavy seas, the destroyers received radar, sonar, and radio signals that they believed signaled another attack by the North Vietnamese navy. For some four hours the ships fired on radar targets and maneuvered vigorously amid electronic and visual reports of enemies. Despite the Navy's claim that two attacking torpedo boats had been sunk, there was no wreckage, bodies of dead North Vietnamese sailors, or other physical evidence present at the scene of the alleged engagement.

President Johnson ordered retaliatory airstrikes on August 4, amid a cloud of confusion among officials in Washington about whether an attack had actually occurred.

At 01:27, Washington time, Herrick sent a cable in which he acknowledged that the second attack may not have happened and that there may actually have been no Vietnamese craft in the area: "Review of action makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful. Freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonarmen may have accounted for many reports. No actual visual sightings by Maddox. Suggest complete evaluation before any further action taken."

One hour later, Herrick sent another cable, stating, "Entire action leaves many doubts except for apparent ambush at beginning. Suggest thorough reconnaissance in daylight by aircraft." In response to requests for confirmation, at around 16:00 Washington time, Herrick cabled, "Details of action present a confusing picture although certain that the original ambush was bona fide." It is likely that McNamara did not inform either the president or Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp Jr. about Herrick's misgivings or Herrick's recommendation for further investigation.

At 18:00 Washington time (05:00 in the Gulf of Tonkin), Herrick cabled yet again, this time stating, "the first boat to close the Maddox probably launched a torpedo at the Maddox which was heard but not seen. All subsequent Maddox torpedo reports are doubtful in that it is suspected that sonarman was hearing the ship's own propeller beat" [sic].

Within thirty minutes of August 4 incident, Johnson had decided on retaliatory attacks (dubbed "Operation Pierce Arrow"). That same day he used the "hot line" to Moscow, and assured the Soviets he had no intent in opening a broader war in Vietnam. Early on August 5, Johnson publicly ordered retaliatory measures stating, "The determination of all Americans to carry out our full commitment to the people and to the government of South Vietnam will be redoubled by this outrage." One hour and forty minutes after his speech, aircraft launched from U.S. carriers reached North Vietnamese targets. On August 5, at 10:40, these planes bombed four torpedo boat bases and an oil-storage facility in Vinh.

The United States' response

Johnson's speech to the American people

Shortly before midnight, on August 4, Johnson interrupted national television to make an announcement in which he described an attack by North Vietnamese vessels on two U.S. Navy warships, Maddox and Turner Joy, and requested authority to undertake a military response. Johnson's speech repeated the theme that "dramatized Hanoi/Ho Chi Minh as the aggressor and which put the United States into a more acceptable defensive posture." Johnson also referred to the attacks as having taken place "on the high seas", suggesting that they had occurred in international waters.

He emphasized commitment to both the American people, and the South Vietnamese government. He also reminded Americans that there was no desire for war. "A close scrutiny of Johnson's public statements ... reveals no mention of preparations for overt warfare and no indication of the nature and extent of covert land and air measures that already were operational." Johnson's statements were short to "minimize the U.S. role in the conflict; a clear inconsistency existed between Johnson's actions and his public discourse."

Reaction from Congress

While Johnson's final resolution was being drafted, US Senator Wayne Morse attempted to hold a fundraiser to raise awareness about possible faulty records of the incident involving Maddox. Morse supposedly received a call from an informant who has remained anonymous urging Morse to investigate official logbooks of Maddox. These logs were not available before Johnson's resolution was presented to Congress.

After urging Congress that they should be wary of Johnson's coming attempt to convince Congress of his resolution, Morse failed to gain enough cooperation and support from his colleagues to mount any sort of movement to stop it. Immediately after the resolution was read and presented to Congress, Morse began to fight it. He contended in speeches to Congress that the actions taken by the United States were actions outside the constitution and were "acts of war rather than acts of defense."

Morse's efforts were not immediately met with support, largely because he revealed no sources and was working with very limited information. It was not until after the United States became more involved in the war that his claim began to gain support throughout the United States government. Morse was defeated when he ran for re-election in 1968.

Distortion of the event

The US government was still seeking evidence on the night of August 4 when Johnson gave his address to the American public on the incident; messages recorded that day indicate that neither Johnson nor McNamara was certain of an attack.

Various news sources, including Time, Life and Newsweek, published articles throughout August on the Tonkin Gulf incident. Time reported: "Through the darkness, from the West and south ... intruders boldly sped ... at least six of them ... they opened fire on the destroyers with automatic weapons, this time from as close as 2,000 yards." Time stated that there was "no doubt in Sharp's mind that the US would now have to answer this attack", and that there was no debate or confusion within the administration regarding the incident.

The use of the set of incidents as a pretext for escalation of U.S. involvement followed the issuance of public threats against North Vietnam, as well as calls from American politicians in favor of escalating the war. On May 4, 1964, William Bundy called for the U.S. to "drive the communists out of South Vietnam", even if that meant attacking both North Vietnam and communist China. Even so, the Johnson administration in the second half of 1964 focused on convincing the American public that there was no chance of war between the United States and North Vietnam.

North Vietnam's General Giap suggested that the DESOTO patrol had been sent into the gulf to provoke North Vietnam into giving the U.S. an excuse for escalation of the war. Various government officials and men aboard Maddox have suggested similar theories. American politicians and strategists had been planning provocative actions against North Vietnam for some time. U.S. Undersecretary of State George Ball told a British journalist after the war that "at that time ... many people ... were looking for any excuse to initiate bombing". George Ball stated that the mission of the destroyer warship involved in the Gulf of Tonkin incident "was primarily for provocation."

According to Raymond McGovern, a retired CIA officer (CIA analyst from 1963 to 1990, and in the 1980s, chairman of the National Intelligence Estimates), the CIA, "not to mention President Lyndon Johnson, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy all knew full well that the evidence of any armed attack on the evening of Aug. 4, 1964, the so-called 'second' Tonkin Gulf incident, was highly dubious. ... During the summer of 1964, President Johnson and the Joint Chiefs of Staff were eager to widen the war in Vietnam. They stepped up sabotage and hit-and-run attacks on the coast of North Vietnam." Maddox, carrying electronic spying gear, was to collect signals intelligence from the North Vietnamese coast, and the coastal attacks were seen as a helpful way to get the North Vietnamese to turn on their coastal radars. For this purpose, it was authorized to approach the coast as close as 13 kilometers (8 mi) and the offshore islands as close as four; the latter had already been subjected to shelling from the sea.

In his book, Body of Secrets, James Bamford, who spent three years in the United States Navy as an intelligence analyst, writes that the primary purpose of the Maddox "was to act as a seagoing provocateur—to poke its sharp gray bow and the American flag as close to the belly of North Vietnam as possible, in effect shoving its five-inch cannons up the nose of the communist navy. ... The Maddox' mission was made even more provocative by being timed to coincide with commando raids, creating the impression that the Maddox was directing those missions ..." Thus, the North Vietnamese had every reason to believe that Maddox was involved in these actions.

Provocative action against North Vietnam was considered after the August 1964 incidents. John McNaughton suggested in September 1964 that the U.S. prepare to take actions to provoke a North Vietnamese military reaction, including plans to use DESOTO patrols North. William Bundy's paper dated September 8, 1964, suggested more DESOTO patrols as well.

Consequences

By early afternoon of August 4, Washington time, Herrick had reported to the Commander in Chief Pacific in Honolulu that "freak weather effects" on the ship's radar had made such an attack questionable. In fact, Herrick was now saying, in a message sent at 1:27 pm Washington time, that no North Vietnamese patrol boats had actually been sighted. Herrick now proposed a "complete evaluation before any further action taken."

McNamara later testified that he had read the message after his return to the Pentagon that afternoon. But he did not immediately call Johnson to tell him that the whole premise of his decision at lunch to approve McNamara's recommendation for retaliatory air strikes against North Vietnam was now highly questionable. Johnson had fended off proposals from McNamara and other advisers for a policy of bombing the North on four occasions since becoming president.

Johnson, who was up for election that year, ordered retaliatory air strikes and went on national television on August 4. Although Maddox had been involved in providing intelligence support for South Vietnamese attacks at Hòn Mê and Hòn Ngư, Johnson denied, in his testimony before Congress, that the U.S. Navy had supported South Vietnamese military operations in the Gulf. He thus characterized the attack as "unprovoked" since the ship had been in international waters.

As a result of his testimony, on August 7, Congress passed a joint resolution (H.J. RES 1145), titled the Southeast Asia Resolution, which granted Johnson the authority to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia without the benefit of a declaration of war. The resolution gave Johnson approval "to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty requesting assistance in defense of its freedom."

Later statements about the incident

Johnson commented privately: "For all I know, our navy was shooting at whales out there."

In 1967, former naval officer, John White, wrote a letter to the editor of the New Haven (CT) Register. He asserted "I maintain that President Johnson, Secretary McNamara and the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave false information to Congress in their report about US destroyers being attacked in the Gulf of Tonkin." White continued his whistleblowing activities in the 1968 documentary In the Year of the Pig. White soon arrived in Washington to meet with Senator Fulbright to discuss his concerns, particularly the faulty sonar reports.

In 1981, Captain Herrick and journalist Robert Scheer re-examined Herrick's ship's log and determined that the first torpedo report from August 4, which Herrick had maintained had occurred—the "apparent ambush"—was in fact unfounded.

Although information obtained well after the fact supported Captain Herrick's statements about the inaccuracy of the later torpedo reports as well as the 1981 Herrick and Scheer conclusion about the inaccuracy of the first, indicating that there was no North Vietnamese attack that night, at the time U.S. authorities and all of the Maddox's crew stated that they were convinced that an attack had taken place. As a result, planes from the aircraft carriers Ticonderoga and Constellation were sent to hit North Vietnamese torpedo boat bases and fuel facilities during Operation Pierce Arrow. Squadron Commander James Stockdale was one of the U.S. pilots flying overhead during the second alleged attack. Stockdale wrote in his 1984 book Love and War: "[I] had the best seat in the house to watch that event, and our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets—there were no PT boats there ... There was nothing there but black water and American fire power." Stockdale at one point recounts seeing Turner Joy pointing her guns at Maddox. Stockdale said his superiors ordered him to keep quiet about this. After he was captured, this knowledge became a heavy burden. He later said he was concerned that his captors would eventually force him to reveal what he knew about the second incident.

In 1995, retired Vietnamese Defense Minister, Võ Nguyên Giáp, meeting with former Secretary McNamara, denied that Vietnamese gunboats had attacked American destroyers on August 4, while admitting to the attack on August 2. A taped conversation of a meeting several weeks after passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was released in 2001, revealing that McNamara expressed doubts to Johnson that the attack had even occurred.

In the fall of 1999, retired Senior CIA Engineering Executive S. Eugene Poteat wrote that he was asked in early August 1964 to determine if the radar operator's report showed a real torpedo boat attack or an imagined one. He asked for further details on time, weather and surface conditions. No further details were forthcoming. In the end he concluded that there were no torpedo boats on the night in question, and that the White House was interested only in confirmation of an attack, not that there was no such attack.

In October 2012 retired Rear Admiral, Lloyd "Joe" Vasey, was interviewed by David Day on Asia Review and gave a detailed account of the August 4 incident. According to Admiral Vasey, who was aboard USS Oklahoma City, a Galveston-class guided missile cruiser, in the Gulf of Tonkin and serving as chief of staff to Commander Seventh Fleet, Turner Joy intercepted an NVA radio transmission ordering a torpedo boat attack on Turner Joy and Maddox. Shortly thereafter, radar contact of "several high speed contacts closing in on them" was acquired by the USS Turner Joy, which locked on to one of the contacts, fired and struck the torpedo boat. There were 18 witnesses, both enlisted and officers, who reported various aspects of the attack; smoke from the stricken torpedo boat, torpedo wakes (reported by four individuals on each destroyer), sightings of the torpedo boats moving through the water and searchlights. All 18 of the witnesses testified at a hearing in Olongapo, Philippines, and their testimony is a matter of public record.

In 2014, as the incident's 50th anniversary approached, John White wrote The Gulf of Tonkin Events—Fifty Years Later: A Footnote to the History of the Vietnam War. In the foreword, he notes "Among the many books written on the Vietnamese war, half a dozen note a 1967 letter to the editor of a Connecticut newspaper which was instrumental in pressuring the Johnson administration to tell the truth about how the war started. The letter was mine." The story discusses Lt. White reading Admiral Stockdale's In Love and War in the mid 1980s, then contacting Stockdale who connected White with Joseph Schaperjahn, chief sonarman on Turner Joy. Schaperjahn confirmed White's assertions that Maddox's sonar reports were faulty and the Johnson administration knew it prior to going to Congress to request support for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. White's book explains the difference between lies of commission and lies of omission. Johnson was guilty of willful lies of omission. White was featured in the August 2014 issue of Connecticut Magazine.

NSA report

In October 2005, The New York Times reported that Robert J. Hanyok, a historian for the U.S. National Security Agency, concluded that the NSA distorted intelligence reports passed to policy makers regarding the August 4, 1964 incident. The NSA historian agency said staff "deliberately skewed" the evidence to make it appear that an attack had occurred.

Hanyok's conclusions were initially published in the Winter 2000/Spring 2001 Edition of Cryptologic Quarterly about five years before the Times article. According to intelligence officials, the view of government historians that the report should become public was rebuffed by policy makers concerned that comparisons might be made to intelligence used to justify the Iraq War (Operation Iraqi Freedom) which commenced in 2003. Reviewing the NSA's archives, Hanyok concluded that the incident began at Phu Bai Combat Base, where intelligence analysts mistakenly believed the destroyers would soon be attacked. This would have been communicated back to the NSA along with evidence supporting such a conclusion, but in fact the evidence did not do that. Hanyok attributed this to the deference that the NSA would have likely given to the analysts who were closer to the event. As the evening progressed, further signals intelligence (SIGINT) did not support any such ambush, but the NSA personnel were apparently so convinced of an attack that they ignored the 90% of SIGINT that did not support that conclusion, and that was also excluded from any reports they produced for the consumption by the President. There was no political motive to their action.

On November 30, 2005, the NSA released a first installment of previously classified information regarding the Gulf of Tonkin incident, including a moderately sanitized version of Hanyok's article. The Hanyok article stated that intelligence information was presented to the Johnson administration "in such a manner as to preclude responsible decision makers in the Johnson administration from having the complete and objective narrative of events." Instead, "only information that supported the claim that the communists had attacked the two destroyers was given to Johnson administration officials."

With regard to why this happened, Hanyok wrote:

As much as anything else, it was an awareness that Johnson would brook no uncertainty that could undermine his position. Faced with this attitude, Ray Cline was quoted as saying "... we knew it was bum dope that we were getting from Seventh Fleet, but we were told only to give facts with no elaboration on the nature of the evidence. Everyone knew how volatile LBJ was. He did not like to deal with uncertainties."

Hanyok included his study of Tonkin Gulf as one chapter in an overall history of NSA involvement and American SIGINT, in the Indochina Wars. A moderately sanitized version of the overall history was released in January 2008 by the National Security Agency and published by the Federation of American Scientists.