Gun violence in the United States results in tens of thousands of deaths and injuries annually. In 2018, the most recent year for which data are available as of 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) National Center for Health Statistics reports 38,390 deaths by firearm, of which 24,432 were by suicide and 13,958 were homicides. The rate of firearm deaths per 100,000 people rose from 10.3 per 100,000 in 1999 to 12 per 100,000 in 2017, with 109 people dying per day, being 11.9 per 100,000 in 2018. In 2010, there were 19,392 firearm-related suicides, and 11,078 firearm-related homicides in the U.S. In 2010, 358 murders were reported involving a rifle while 6,009 were reported involving a handgun; another 1,939 were reported with an unspecified type of firearm.

About 1.4 million people have died from firearms in the U.S. between 1968 and 2011. This number includes all deaths resulting from a firearm, including suicides, homicides, and accidents.

Compared to 22 other high-income nations, the U.S. gun-related homicide rate is 25 times higher. Although it has half the population of the other 22 nations combined, among those 22 nations studied, the U.S. had 82 percent of gun deaths, 90 percent of all women killed with guns, 91 percent of children under 14 and 92 percent of young people between ages 15 and 24 killed with guns. The ownership and regulation of guns are among the most widely debated issues in the country.

Gun violence against other persons is most common in poor urban areas and is frequently associated with gang violence, often involving male juveniles or young adult males. Although mass shootings are covered extensively in the media, mass shootings in the United States account for only a small fraction of gun-related deaths. School shootings are described as a "uniquely American crisis", according to The Washington Post in 2018. Children at U.S. schools have active shooter drills. According to USA Today, in 2019 “about 95% of public schools now have students and teachers practice huddling in silence, hiding from an imaginary gunman.”

Legislation at the federal, state, and local levels has attempted to address gun violence through a variety of methods, including restricting firearms purchases by youths and other "at-risk" populations, setting waiting periods for firearm purchases, establishing gun buyback programs, law enforcement and policing strategies, stiff sentencing of gun law violators, education programs for parents and children, and community-outreach programs.

Gun ownership

The Congressional Research Service in 2009 estimated there were 310 million firearms in the U.S., not including weapons owned by the military. Of these, 114 million were handguns, 110 million were rifles, and 86 million were shotguns. In that same year, the Census bureau stated the population of people in the U.S. at 306 million. Accurate figures for civilian gun ownership are difficult to determine. While the number of guns in civilian hands has been on the increase, the percentage of Americans and American households who claim to own guns has been in long-term decline, according to the General Social Survey. It found that gun ownership by households has declined steadily from about half, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, down to 32% in 2015. The percentage of individual owners declined from 31% in 1985 to 22% in 2014. However, the Gallup organization has been performing similar polls for the same interval, and finds that household ownership of firearms was about the same in 2013 as it was in 1970 – 43%, and individual ownership numbers rose from 27% in 2000, to 29% in 2013.

Household firearms ownership hit a high in 1993–1994 when household gun ownership exceeded 50%, according to Gallup polls. In 2016, household firearm ownership still exceeded 35%, and there was a long-term trend of declining support for stricter gun control laws. Gallup polling has consistently shown two-thirds opposition to bans on handgun possession.

Gun ownership figures are generally estimated via polling, by such organizations as the General Social Survey (GSS), Harris Interactive, and Gallup. There are significant disparities in the results across polls by different organizations, calling into question their reliability. In Gallup's 1972 survey, 43% reported having a gun in their home, while GSS's 1973 survey resulted in 49% reporting a gun in the home; in 1993, Gallup's poll results were 51%, while GSS's 1994 poll showed 43%. In 2012, Gallup's survey showed 47% of Americans reporting having a gun in their home, while the GSS in 2012 reports 34%.

In 1997, estimates were about 44 million gun owners in the United States. These owners possessed around 192 million firearms, of which an estimated 65 million were handguns. A National Survey on Private Ownership and Use of Firearms (NSPOF), conducted in 1994, indicated that Americans owned 192 million guns: 36% rifles, 34% handguns, 26% shotguns, and 4% other types of long guns. Most firearm owners owned multiple firearms, with the NSPOF survey indicating 25% of adults owned firearms. In the U.S., 11% of households reported actively being involved in hunting, with the remaining firearm owners having guns for self-protection and other reasons. Throughout the 1970s and much of the 1980s, the rate of gun ownership in the home ranged from 45–50%. After highly publicized mass murders, it is consistently observed that there are rapid increases in gun purchases and exceptionally large crowds at gun vendors and gun shows, due to fears of increased gun control.

Gun ownership also varied across geographic regions, ranging from 25% rates of ownership in the Northeastern United States to 60% rates of ownership in the East South Central States. A Gallup poll (2004) indicated that 49% of men reported gun ownership, compared to 33% of women, and 44% of whites owned a gun, compared to only 24% of nonwhites. More than half of those living in rural areas (56%) owned a gun, compared with 40% of suburbanites and 29% of those in urban areas. More than half (53%) of Republicans owned guns, compared with 36% of political independents and 31% of Democrats. One criticism of the GSS survey and other proxy measures of gun ownership, is that they do not provide adequate macro-level detail to allow conclusions on the relationship between overall firearm ownership and gun violence. Gary Kleck compared various survey and proxy measures and found no correlation between overall firearm ownership and gun violence. In contrast, studies by David Hemenway and his colleagues, which used GSS data and the fraction of suicides committed with a gun as a proxy for gun ownership rates, found a strong positive association between gun ownership and homicide in the United States. Similarly, a 2006 study by Philip J. Cook and Jens Ludwig, which also used the percent of suicides committed with a gun as a proxy, found that gun prevalence increased homicide rates. This study also found that the elasticity of this effect was between +0.1 and +0.3.

Self-protection

The effectiveness and safety of guns used for personal defense is debated. Studies place the instances of guns used in personal defense as low as 65,000 times per year, and as high as 2.5 million times per year. Under President Bill Clinton, the Department of Justice conducted a survey in 1994 that placed the usage rate of guns used in personal defense at 1.5 million times per year, but noted this was likely to be an overestimate.

Between 1987 and 1990, David McDowall et al. found that guns were used in defense during a crime incident 64,615 times annually (258,460 times total over the whole period). This equated to two times out of 1,000 criminal incidents (0.2%) that occurred in this period, including criminal incidents where no guns were involved at all. For violent crimes, assault, robbery, and rape, guns were used 0.83% of the time in self-defense. Of the times that guns were used in self-defense, 71% of the crimes were committed by strangers, with the rest of the incidents evenly divided between offenders that were acquaintances or persons well known to the victim. In 28% of incidents where a gun was used for self-defense, victims fired the gun at the offender. In 20% of the self-defense incidents, the guns were used by police officers. During this same period, 1987 to 1990, there were 11,580 gun homicides per year (46,319 total), and the National Crime Victimization Survey estimated that 2,628,532 nonfatal crimes involving guns occurred.

McDowall's study for the American Journal of Public Health contrasted with a 1995 study by Gary Kleck and Marc Gertz, which found that 2.45 million crimes were thwarted each year in the U.S. using guns, and in most cases, the potential victim never fired a shot. The results of the Kleck studies have been cited many times in scholarly and popular media. The methodology of the Kleck and Gertz study has been criticized by some researchers but also defended by gun-control advocate Marvin Wolfgang.

Using cross-sectional time-series data for U.S. counties from 1977 to 1992, Lott and Mustard of the Law School at the University of Chicago found that allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons deters violent crimes and appears to produce no increase in accidental deaths. They claimed that if those states which did not have right-to-carry concealed gun provisions had adopted them in 1992, approximately 1,570 murders; 4,177 rapes; and over 60,000 aggravate assaults would have been avoided yearly.

Suicides

In the U.S., most people who die of suicide use a gun, and most deaths by gun are suicides.

There were 19,392 firearm-related suicides in the U.S. in 2010. In 2017, over half of the nation's 47,173 suicides involved a firearm. The U.S. Department of Justice reports that about 60% of all adult firearm deaths are by suicide, 61% more than deaths by homicide. One study found that military veterans used firearms in about 67% of suicides in 2014. Firearms are the most lethal method of suicide, with a lethality rate 2.6 times higher than suffocation (the second-most lethal method).

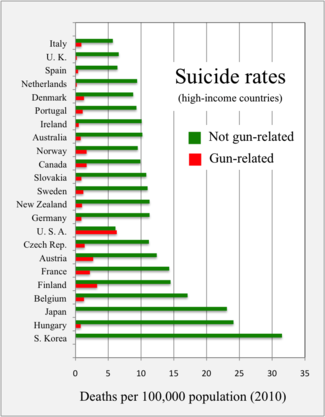

In the United States, access to firearms is associated with an increased risk of completed suicide. A 1992 case-control study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed an association between estimated household firearm ownership and suicide rates, finding that individuals living in a home where firearms are present are more likely to successfully commit suicide than those individuals who do not own firearms, by a factor of 3 or 4. A 2006 study by researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health found a significant association between changes in estimated household gun ownership rates and suicide rates in the United States among men, women, and children. A 2007 study by the same research team found that in the United States, estimated household gun ownership rates were strongly associated with overall suicide rates and gun suicide rates, but not with non-gun suicide rates. A 2013 study reproduced this finding, even after controlling for different underlying rates of suicidal behavior by states. A 2015 study also found a strong association between estimated gun ownership rates in American cities and rates of both overall and gun suicide, but not with non-gun suicide. Correlation studies comparing different countries do not always find a statistically significant effect. A 2016 cross-sectional study showed a strong association between estimated household gun ownership rates and gun-related suicide rates among men and women in the United States. The same study found a strong association between estimated gun ownership rates and overall suicide rates, but only in men. During the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a strong upward trend in adolescent suicides with guns as well as a sharp overall increase in suicides among those age 75 and over. A 2018 study found that temporary gun seizure laws were associated with a 13.7% reduction in firearm suicides in Connecticut and a 7.5% reduction in firearm suicides in Indiana.

David Hemenway, professor of health policy at Harvard University's School of Public Health, and director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center and the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center, stated

Differences in overall suicide rates across cities, states and regions in the United States are best explained not by differences in mental health, suicide ideation, or even suicide attempts, but by availability of firearms. Many suicides are impulsive, and the urge to die fades away. Firearms are a swift and lethal method of suicide with a high case-fatality rate.

There are over twice as many gun-related suicides than gun-related homicides in the United States. Firearms are the most popular method of suicide due to the lethality of the weapon. 90% of all suicides attempted using a firearm result in a fatality, as opposed to less than 3% of suicide attempts involving cutting or drug-use. The risk of someone attempting suicide is also 4.8 times greater if they are exposed to a firearm on a regular basis; for example, in the home.

Homicides

Statistics

Unlike other high-income OECD countries, most homicides in the U.S. are gun homicides. In the U.S. in 2011, 67 percent of homicide victims were killed using a firearm: 66 percent of single-victim homicides and 79 percent of multiple-victim homicides.

In 1993, there were seven gun homicides for every 100,000 people; by 2013, that figure had fallen to 3.6, according to Pew Research.[77]

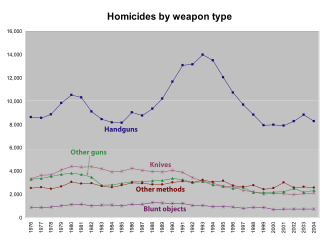

The FBI further breaks down gun homicides by weapon type. Handguns have been consistently responsible for the majority of fatalities.

- In 2016, there were 11,004 gun homicides (65% handguns, 6% rifle/shotgun, 30% other/unknown type)

- In 2014, there were 8,124 gun homicides (68% handguns, 6% rifle/shotgun, 25% other/unknown type).

- In 2010, there were 8,775 gun homicides (68% handguns, 8% rifle/shotgun, 23% other/unknown type).

- In 2001, there were 8,890 gun homicides (78% handguns, 10% rifle/shotguns, 12% other/unknown type).

The Centers for Disease Control reports that there were 11,078 gun homicides in the U.S. in 2010. This is higher than the FBI's count.

History

In the 19th century gun violence played a role in civil disorder such as the Haymarket riot. Homicide rates in cities such as Philadelphia were significantly lower in the 19th century than in modern times. During the 1980s and early 1990s, homicide rates surged in cities across the United States (see graphs at right). Handgun homicides accounted for nearly all of the overall increase in the homicide rate, from 1985 to 1993, while homicide rates involving other weapons declined during that time frame. The rising trend in homicide rates during the 1980s and early 1990s was most pronounced among lower income and especially unemployed males. Youths and Hispanic and African American males in the U.S. were the most represented, with the injury and death rates tripling for black males aged 13 through 17 and doubling for black males aged 18 through 24. The rise in crack cocaine use in cities across the U.S. is often cited as a factor for increased gun violence among youths during this time period.

Demographics of risk

Prevalence of homicide and violent crime is higher in statistical metropolitan areas of the U.S. than it is in non-metropolitan counties; the vast majority of the U.S. population lives in statistical metropolitan areas. In metropolitan areas, the homicide rate in 2013 was 4.7 per 100,000 compared with 3.4 in non-metropolitan counties. More narrowly, the rates of murder and non-negligent manslaughter are identical in metropolitan counties and non-metropolitan counties. In U.S. cities with populations greater than 250,000, the mean homicide rate was 12.1 per 100,000. According to FBI statistics, the highest per capita rates of gun-related homicides in 2005 were in Washington, D.C. (35.4/100,000), Puerto Rico (19.6/100,000), Louisiana (9.9/100,000), and Maryland (9.9/100,000). In 2017, according to the Associated Press, Baltimore broke a record for homicides.

In 2005, the 17-24 age group was significantly over-represented in violent crime statistics, particularly homicides involving firearms. In 2005, 17-19-year-olds were 4.3% of the overall population of the U.S. but 11.2% of those killed in firearm homicides. This age group also accounted for 10.6% of all homicide offenses. The 20-24-year-old age group accounted for 7.1% of the population, but 22.5% of those killed in firearm homicides. The 20-24 age group also accounted for 17.7% of all homicide offenses.

Those under 17 are not overrepresented in homicide statistics. In 2005, 13-16-year-olds accounted for 6% of the overall population of the U.S., but only 3.6% of firearm homicide victims, and 2.7% of overall homicide offenses.

People with a criminal record are more likely to die as homicide victims. Between 1990 and 1994, 75% of all homicide victims age 21 and younger in the city of Boston had a prior criminal record. In Philadelphia, the percentage of those killed in gun homicides that had prior criminal records increased from 73% in 1985 to 93% in 1996. In Richmond, Virginia, the risk of gunshot injury is 22 times higher for those males involved with crime.

It is significantly more likely that a death will result when either the victim or the attacker has a firearm. The mortality rate for gunshot wounds to the heart is 84%, compared to 30% for people who suffer stab wounds to the heart.

In the United States, states with higher gun ownership rates have higher rates of gun homicides and homicides overall, but not higher rates of non-gun homicides. Higher gun availability is positively associated with homicide rates. However, there is evidence, that gun ownership has more of an effect on rates of gun suicide than it does on gun homicide.

Some studies suggest that the concept of guns can prime aggressive thoughts and aggressive reactions. An experiment by Berkowitz and LePage in 1967 examined this "weapons effect." Ultimately, when study participants were provoked, their reaction was substantially more aggressive when a gun (in contrast with a more benign object like a tennis racket) was visibly present in the room. Other similar experiments like those conducted by Carson, Marcus-Newhall and Miller yield similar results. Such results imply that the presence of a gun in an altercation could elicit an aggressive reaction which may result in homicide. However, the demonstration of such reactions in experimental settings does not entail that this would be true in reality.

Comparison to other countries

The U.S. is ranked 4th out of 34 developed nations for the highest incidence rate of homicides committed with a firearm, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data. Mexico, Turkey, Estonia are ranked ahead of the U.S. in incidence of homicides. A U.S. male aged 15–24 is 70 times more likely to be killed with a gun than their counterpart in the eight (G-8) largest industrialized nations in the world (United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, Canada, Italy, Russia). In a broader comparison of 218 countries the U.S. is ranked 111. In 2010, the U.S.' homicide rate is 7 times higher than the average for populous developed countries in the OECD, and its firearm-related homicide rate was 25.2 times higher. In 2013 the United States' firearm-related death rate was 10.64 deaths for every 100,000 inhabitants, a figure very close to Mexico's 11.17, although in Mexico firearm deaths are predominantly homicides whereas in the United States they are predominantly suicides. (Although Mexico has strict gun laws, the laws restricting carry are often unenforced, and the laws restricting manufacture and sale are often circumvented by trafficking from the United States and other countries.) Canada and Switzerland each have much looser gun control regulation than the majority of developed nations, although significantly more than in the United States, and have firearm death rates of 2.22 and 2.91 per 100,000 citizens, respectively. By comparison Australia, which imposed sweeping gun control laws in response to the Port Arthur massacre in 1996, has a firearm death rate of 0.86 per 100,000, and in the United Kingdom the rate is 0.26. In the year of 2014, there were a total of 8,124 gun homicides in the U.S. In 2015, there were 33,636 deaths due to firearms in the U.S, with homicides accounting for 13,286 of those, while guns were used to kill about 50 people in the U.K., a country with population one fifth of the size of the U.S. population. More people are typically killed with guns in the U.S. in a day (about 85) than in the U.K. in a year, if suicides are included. With deaths by firearm reaching almost 40,000 in the U.S. in 2017, their highest level since 1968, almost 109 people died per day. A study conducted by the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2018, states that the worldwide gun death reach 250,000 Yearly and the United States is among just six countries that make up half of those fatalities.

Mass shootings

The definition of a mass shooting is still under debate. The precise inclusion criteria are disputed, and there is no broadly accepted definition. Mother Jones, using their standard of a mass shooting where a lone gunman kills at least four people in a public place for motivations excluding gang violence or robbery, concluded that between 1982 and 2006 there were 40 mass shootings (an average of 1.6 per year). More recently, from 2007 through May 2018, there have been 61 mass shootings (an average of 5.4 per year). More broadly, the frequency of mass shootings steadily declined throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, then increased dramatically.

Studies indicate that the rate at which public mass shootings occur has tripled since 2011. Between 1982 and 2011, a mass shooting occurred roughly once every 200 days. However, between 2011 and 2014 that rate has accelerated greatly with at least one mass shooting occurring every 64 days in the United States. In "Behind the Bloodshed", a report by USA Today, said that there were mass killings every two weeks and that public mass killings account for 1 in 6 of all mass killings (26 killings annually would thus be equivalent to 26/6, 4 to 5, public killings per year). Mother Jones listed seven mass shootings in the U.S. for 2015. The average for the period 2011–2015 was about 5 a year. An analysis by Michael Bloomberg's gun violence prevention group, Everytown for Gun Safety, identified 110 mass shootings, defined as shootings in which at least four people were murdered with a firearm, between January 2009 and July 2014; at least 57% were related to domestic or family violence. This would imply that not more than 43% of 110 shootings in 5.5 years were non-domestic, though not necessarily public or indiscriminate; this equates to 8.6 per year, broadly in line with the other figures.

Other media outlets have reported that hundreds of mass shootings take place in the United States in a single calendar year, citing a crowd-funded website known as Shooting Tracker which defines a mass shooting as having four or more people injured or killed. In December 2015, The Washington Post reported that there had been 355 mass shootings in the United States so far that year. In August 2015, The Washington Post reported that the United States was averaging one mass shooting per day. An earlier report had indicated that in 2015 alone, there had been 294 mass shootings that killed or injured 1,464 people. Shooting Tracker and Mass Shooting Tracker, the two sites that the media have been citing, have been criticized for using a criterion much more inclusive than that used by the government—they count four victims injured as a mass shooting—thus producing much higher figures.

Handguns figured in the Virginia Tech shooting, the Binghamton shootings, the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, the Oikos University shooting, and the 2011 Tucson shooting, but both a handgun and a rifle were used in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. The Aurora theater shooting and the Columbine High School massacre were committed by assailants armed with multiple weapons. AR-15 style rifles have been used in a number of the deadliest mass shooting incidents, and have come to be widely characterized as the weapon of choice for perpetrators of mass shootings, despite statistics which show that handguns are the most commonly used weapon type in mass shootings.

In recent years, the number of public mass shootings has increased substantially, with a steady increase in gun related deaths. Although mass shootings are covered extensively in the media, they account for a small fraction of gun-related deaths (only 1 percent of all gun deaths between 1980 and 2008).

Between Jan 1 and May 18, 2018, 31 students and teachers were killed inside U.S. schools. That exceeds the number of U.S. military servicemembers who died in combat and noncombat roles during the same period.

Accidental and negligent injuries

The perpetrators and victims of accidental and negligent gun discharges may be of any age. Accidental injuries are most common in homes where guns are kept for self-defense. The injuries are self-inflicted in half of the cases. On January 16, 2013, President Obama issued 23 Executive Orders on Gun Safety, one of which was for the Center for Disease Control (CDC) to research causes and possible prevention of gun violence. The five main areas of focus were gun violence, risk factors, prevention/intervention, gun safety and how media and violent video games influence the public. They also researched the area of accidental firearm deaths. According to this study not only have the number of accidental firearm deaths been on the decline over the past century but they now account for less than 1% of all unintentional deaths, half of which are self-inflicted.

Violent crime

In the United States, areas with higher levels of gun ownership have an increased risk of gun assault and gun robbery. However it is unclear if higher crime rates are a result of increased gun ownership or if gun ownership rates increase as a result of increased crime.

Costs

In 2000, the costs of gun violence in the United States were estimated to be on the order of $100 billion per year, plus the costs associated with the gun violence avoidance and prevention behaviors.

In 2010, gun violence cost U.S. taxpayers about $516 million in direct hospital costs.

U.S. presidential assassinations and attempts

At least eleven assassination attempts with firearms have been made on U.S. presidents (over one-fifth of all presidents); four were successful, three with handguns and one with a rifle.

Abraham Lincoln survived an earlier attack, but was killed using a .44-caliber Derringer pistol fired by John Wilkes Booth. James A. Garfield was shot two times and mortally wounded by Charles J. Guiteau using a .44-caliber revolver on July 2, 1881. He would die of pneumonia the same year on September 19. On September 6, 1901, William McKinley was fatally wounded by Leon Czolgosz when he fired twice at point-blank range using a .32-caliber revolver. Despite only being struck by one of the bullets and receiving immediate surgical treatment, McKinley died 8 days later of gangrene infection. John F. Kennedy was killed by Lee Harvey Oswald with a bolt-action rifle on November 22, 1963.

Andrew Jackson, Harry S. Truman, and Gerald Ford (the latter twice) survived assassination attempts involving firearms unharmed.

Ronald Reagan was critically wounded in the March 30, 1981 assassination attempt by John Hinckley, Jr. with a .22-caliber revolver. He remains the only U.S. President to survive being shot while in office. Former president Theodore Roosevelt was shot and wounded right before delivering a speech during his 1912 presidential campaign. Despite bleeding from his chest, Roosevelt refused to go to a hospital until he delivered the speech. On February 15, 1933, Giuseppe Zangara attempted to assassinate president-elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was giving a speech from his car in Miami, Florida. Although Roosevelt was unharmed, Chicago mayor Anton Cermak died in that attempt, and several other bystanders received non-fatal injuries.

Response to these events has resulted in federal legislation to regulate the public possession of firearms. For example, the attempted assassination of Franklin Roosevelt contributed to passage of the National Firearms Act of 1934, and the Kennedy assassination (along with others) resulted in the Gun Control Act of 1968. The GCA is a federal law signed by President Lyndon Johnson that broadly regulates the firearms industry and firearms owners. It primarily focuses on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by largely prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except among licensed manufacturers, dealers, and importers.

Other violent crime

A quarter of robberies of commercial premises in the U.S. are committed with guns. Fatalities are three times as likely in robberies committed with guns than where other, or no, weapons are used, with similar patterns in cases of family violence. Criminologist Philip J. Cook hypothesized that if guns were less available, criminals might commit the same crime, but with less-lethal weapons. He finds that the level of gun ownership in the 50 largest U.S. cities correlates with the rate of robberies committed with guns, but not with overall robbery rates. He also finds that robberies in which the assailant uses a gun are more likely to result in the death of the victim, but less likely to result in injury to the victim. Overall robbery and assault rates in the U.S. are comparable to those in other developed countries, such as Australia and Finland, with much lower levels of gun ownership. A strong association exists between the availability of illegal guns and violent crime rates, but not between legal gun availability and violent crime rates.

Offenders

Considering mass shootings alone (sometimes defined as at least four people shot dead in a public place), nearly all shooters are male. A database of 101 mass shootings between 1982 and 2018 recorded 98 male shooters, 2 female shooters, and one partnership of a male and female shooter. The race of the shooters included 58 whites, 16 blacks, 8 Asians, 7 Latinos, 3 Native Americans, and 8 unknown/other.[181][182]

Vectors

In 2015, Arizona State University researcher Sherry Towers said "National news media attention is like a 'vector' that reaches people who are vulnerable." She stated that disaffected people can become infected by the attention given other disturbed people who have become mass killers.

Victims

African Americans suffer a disproportionate share of firearm homicides. African Americans, who were only 13% of the U.S. population in 2010, were 55% of the victims of gun homicide. Non-Hispanic whites were 65% of the U.S. population in 2010, but only 25% of the victims. Hispanics were 16% of the population in 2010 but 17% of victims.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, from 1980 to 2008, 84% of white homicide victims were killed by white offenders and 93% of black homicide victims were killed by black offenders.

Public policy

Public policy as related to preventing gun violence is an ongoing political and social debate regarding both the restriction and availability of firearms within the United States. Policy at the Federal level is/has been governed by the Second Amendment, National Firearms Act, Gun Control Act of 1968, Firearm Owners Protection Act, Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, and the Domestic Violence Offender Act. Gun policy in the U.S. has been revised many times with acts such as the Firearm Owners Protection Act, which loosened provisions for gun sales while also strengthening automatic firearms law.

At the federal, state and local level, gun laws such as handgun bans have been overturned by the Supreme Court in cases such as District of Columbia v. Heller and McDonald v. Chicago. These cases hold that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm. Columbia v. Heller only addressed the issue on Federal enclaves, while McDonald v. Chicago addressed the issue as relating to the individual states.

Gun control proponents often cite the relatively high number of homicides committed with firearms as reason to support stricter gun control laws. Policies and laws that reduce homicides committed with firearms prevent homicides overall; a decrease in firearm-related homicides is not balanced by an increase in non-firearm homicides. Firearm laws are a subject of debate in the U.S., with firearms used for recreational purposes as well as for personal protection. Gun rights advocates cite the use of firearms for self-protection, and to deter violent crime, as reasons why more guns can reduce crime. Gun rights advocates also say criminals are the least likely to obey firearms laws, and so limiting access to guns by law-abiding people makes them more vulnerable to armed criminals.

In a survey of 41 studies, half of the studies found a connection between gun ownership and homicide but these were usually the least rigorous studies. Only six studies controlled at least six statistically significant confounding variables, and none of them showed a significant positive effect. Eleven macro-level studies showed that crime rates increase gun levels (not vice versa). The reason that there is no opposite effect may be that most owners are noncriminals and that they may use guns to prevent violence.

Access to firearms

The US Constitution enshrines the right to gun ownership in the Second Amendment of the United States Bill of Rights to ensure the security of a free state through a well regulated Militia. It states: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed." The Constitution makes no distinction between the type of firearm in question or state of residency.

Gun dealers in the U.S. are prohibited from selling handguns to those under the age of 21, and long guns to those under the age of 18. In 2017, the National Safety Council released a state ranking on firearms access indicators such as background checks, waiting periods, safe storage, training, and sharing of mental health records with the NICS database to restrict firearm access.

Assuming access to guns, the top ten guns involved in crime in the U.S. show a definite tendency to favor handguns over long guns. The top ten guns used in crime, as reported by the ATF in 1993, were the Smith & Wesson .38 Special and .357 revolvers; Raven Arms .25 caliber, Davis P-380 .380 caliber, Ruger .22 caliber, Lorcin L-380 .380 caliber, and Smith & Wesson semi-automatic handguns; Mossberg and Remington 12 gauge shotguns; and the Tec DC-9 9 mm handgun. An earlier 1985 study of 1,800 incarcerated felons showed that criminals preferred revolvers and other non-semi-automatic firearms over semi-automatic firearms. In Pittsburgh a change in preferences towards pistols occurred in the early 1990s, coinciding with the arrival of crack cocaine and the rise of violent youth gangs.

Background checks in California from 1998 to 2000 resulted in 1% of sales being initially denied. The types of guns most often denied included semiautomatic pistols with short barrels and of medium caliber. A 2018 study determined that California's implementation of comprehensive background checks and misdemeanor violation policies was not associated with a net change in the firearm homicide rate over the ensuing 10 years. A 2018 study found no evidence of an association between the repeal of comprehensive background check policies and firearm homicide and suicide rates in Indiana and Tennessee.

Among juveniles (minors under the age of 16, 17, or 18, depending on legal jurisdiction) serving in correctional facilities, 86% had owned a gun, with 66% acquiring their first gun by age 14. There was also a tendency for juvenile offenders to have owned several firearms, with 65% owning three or more. Juveniles most often acquired guns illegally from family, friends, drug dealers, and street contacts. Inner city youths cited "self-protection from enemies" as the top reason for carrying a gun. In Rochester, New York, 22% of young males have carried a firearm illegally, most for only a short time. There is little overlap between legal gun ownership and illegal gun carrying among youths.

One 2006 study concluded that "suicide, murder and violent crime rates are determined by basic social, economic and/or cultural factors with the availability of any particular one of the world's myriad deadly instrument being irrelevant." However, A 2011 study indicated that in states where local background checks for gun purchases are completed, the suicide and homicide rates were much lower than states without.

Firearms market

Gun rights advocates argue that policy aimed at the supply side of the firearms market is based on limited research. One consideration is that 60–70% of firearms sales in the U.S. are transacted through federally licensed firearm dealers, with the remainder taking place in the "secondary market", in which previously owned firearms are transferred by non-dealers. Access to secondary markets is generally less convenient to purchasers, and involves such risks as the possibility of the gun having been used previously in a crime. Unlicensed private sellers were permitted by law to sell privately owned guns at gun shows or at private locations in 24 states as of 1998. Regulations that limit the number of handgun sales in the primary, regulated market to one handgun a month per customer have been shown to be effective at reducing illegal gun trafficking by reducing the supply into the secondary market. Taxes on firearm purchases are another means for government to influence the primary market.

Criminals tend to obtain guns through multiple illegal pathways, including large-scale gun traffickers, who tend to provide criminals with relatively few guns. Federally licensed firearm dealers in the primary (new and used gun) market are regulated by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF). Firearm manufacturers are required to mark all firearms manufactured with serial numbers. This allows the ATF to trace guns involved in crimes back to their last Federal Firearms License (FFL) reported change of ownership transaction, although not past the first private sale involving any particular gun. A report by the ATF released in 1999 found that 0.4% of federally licensed dealers sold half of the guns used criminally in 1996 and 1997. This is sometimes done through "straw purchases." State laws, such as those in California, that restrict the number of gun purchases in a month may help stem such "straw purchases." States with gun registration and licensing laws are generally less likely to have guns initially sold there used in crimes. Similarly, crime guns tend to travel from states with weak gun laws to states with strict gun laws. An estimated 500,000 guns are stolen each year, becoming available to prohibited users. During the ATF's Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative (YCGII), which involved expanded tracing of firearms recovered by law enforcement agencies, only 18% of guns used criminally that were recovered in 1998 were in possession of the original owner. Guns recovered by police during criminal investigations were often sold by legitimate retail sales outlets to legal owners, and then diverted to criminal use over relatively short times ranging from a few months to a few years, which makes them relatively new compared with firearms in general circulation.

A 2016 survey of prison inmates by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 43% of guns used in crimes were obtained from the black market, 25% from an individual, 10% from a retail source (including 0.8% from a gun show), and 6% from theft.

Federal legislation

The first Federal legislation related to firearms was the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution ratified in 1791. For 143 years, this was the only major Federal legislation regarding firearms. The next Federal firearm legislation was the National Firearms Act of 1934, which created regulations for the sale of firearms, established taxes on their sale, and required registration of some types of firearms such as machine guns.

In the aftermath of the Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. assassinations, the Gun Control Act of 1968 was enacted. This Act regulated gun commerce, restricting mail order sales, and allowing shipments only to licensed firearm dealers. The Act also prohibited sale of firearms to felons, those under indictment, fugitives, illegal aliens, drug users, those dishonorably discharged from the military, and those in mental institutions. The law also restricted importation of so-called Saturday night specials and other types of guns, and limited the sale of automatic weapons and semi-automatic weapon conversion kits.

The Firearm Owners Protection Act, also known as the McClure-Volkmer Act, was passed in 1986. It changed some restrictions in the 1968 Act, allowing federally licensed gun dealers and individual unlicensed private sellers to sell at gun shows, while continuing to require licensed gun dealers to require background checks. The 1986 Act also restricted the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms from conducting punitively repetitive inspections, reduced the amount of record-keeping required of gun dealers, raised the burden of proof for convicting gun law violators, and changed restrictions on convicted felons from owning firearms. In addition it also banned new machine guns for sale to the public, but grandfathered in any that were already registered.

In the years following the passage of the Gun Control Act of 1968, people buying guns were required to show identification and sign a statement affirming that they were not in any of the prohibited categories. Many states enacted background check laws that went beyond the federal requirements. The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act passed by Congress in 1993 imposed a waiting period before the purchase of a handgun, giving time for, but not requiring, a background check to be made. The Brady Act also required the establishment of a national system to provide instant criminal background checks, with checks to be done by firearms dealers. The Brady Act only applied to people who bought guns from licensed dealers, whereas felons buy some percentage of their guns from black market sources. Restrictions, such as waiting periods, impose costs and inconveniences on legitimate gun purchasers, such as hunters. A 2000 study found that the implementation of the Brady Act was associated with "reductions in the firearm suicide rate for persons aged 55 years or older but not with reductions in homicide rates or overall suicide rates."

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, enacted in 1994, included the Federal Assault Weapons Ban, and was a response to public fears over mass shootings. This provision prohibited the manufacture and importation of some firearms with certain features such as a folding stock, pistol grip, flash suppressor, and magazines holding more than ten rounds. A grandfather clause was included that allowed firearms manufactured before 1994 to remain legal. A short-term evaluation by University of Pennsylvania criminologists Christopher S. Koper and Jeffrey A. Roth did not find any clear impact of this legislation on gun violence. Given the short study time period of the evaluation, the National Academy of Sciences advised caution in drawing any conclusions. In September 2004, the assault weapon ban expired, with its sunset clause.

The Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban, the Lautenberg Amendment, prohibited anyone previously convicted of a misdemeanor or felony crime of domestic violence from shipment, transport, ownership and use of guns or ammunition. This was ex post facto, in the opinion of Representative Bob Barr. This law also prohibited the sale or gift of a firearm or ammunition to such a person. It was passed in 1996, and became effective in 1997. The law does not exempt people who use firearms as part of their duties, such as police officers or military personnel with applicable criminal convictions; they may not carry firearms.

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, police and National Guard units in New Orleans confiscated firearms from private citizens in an attempt to prevent violence. In reaction, Congress passed the Disaster Recovery Personal Protection Act of 2006 in the form of an amendment to Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2007. Section 706 of the Act prohibits federal employees and those receiving federal funds from confiscating legally possessed firearms during a disaster.

On January 5, 2016, President Obama unveiled his new strategy to curb gun violence in America. His proposals focus on new background check requirements that are intended to enhance the effectiveness of the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), and greater education and enforcement efforts of existing laws at the state level. In an interview with Bill Simmons of HBO, President Obama also confirmed that gun control will be the "dominant" issue on his agenda in his last year of presidency.

State legislation

Right-to-carry

All 50 U.S. states allow for the right to carry firearms. A majority of states either require a shall-issue permit or allow carrying without a permit and a minority require a may-issue permit. Right-to-carry laws expanded in the 1990s as homicide rates from gun violence in the U.S. increased, largely in response to incidents such as the Luby's shooting of 1991 in Texas which directly resulted in the passage of a carrying concealed weapon, or CCW, law in Texas in 1995. As Rorie Sherman, staff reporter for the National Law Journal wrote in an article published on April 18, 1994, "It is a time of unparalleled desperation about crime. But the mood is decidedly 'I'll do it myself' and 'Don't get in my way.'"

The result was laws, or the lack thereof, that permitted persons to carry firearms openly, known as open carry, often without any permit required, in 22 states by 1998. Laws that permitted persons to carry concealed handguns, sometimes termed a concealed handgun license, CHL, or concealed pistol license, CPL in some jurisdictions instead of CCW, existed in 34 states in the U.S. by 2004. Since then, the number of states with CCW laws has increased; as of 2014, all 50 states have some form of CCW laws on the books.

Economist John Lott has argued that right-to-carry laws create a perception that more potential crime victims might be carrying firearms, and thus serve as a deterrent against crime. Lott's study has been criticized for not adequately controlling for other factors, including other state laws also enacted, such as Florida's laws requiring background checks and waiting period for handgun buyers. When Lott's data was re-analyzed by some researchers, the only statistically significant effect of concealed-carry laws found was an increase in assaults, with similar findings by Jens Ludwig. Lott and Mustard's 1997 study has also been criticized by Paul Rubin and Hashem Dezhbakhsh for inappropriately using a dummy variable; Rubin and Dezhbakhsh reported in a 2003 study that right-to-carry laws have much smaller and more inconsistent effects than those reported by Lott and Mustard, and that these effects are usually not crime-reducing. Since concealed-carry permits are only given to adults, Philip J. Cook suggested that analysis should focus on the relationship with adult and not juvenile gun incident rates. He found no statistically significant effect. A 2004 National Academy of Science survey of existing literature found that the data available "are too weak to support unambiguous conclusions" about the impact of right-to-carry laws on rates of violent crime. NAS suggested that new analytical approaches and datasets at the county or local level are needed to adequately evaluate the impact of right-to-carry laws. A 2014 study found that Arizona's SB 1108, which allowed adults in the state to concealed carry without a permit and without passing a training course, was associated with an increase in gun-related fatalities. A 2018 study by Charles Manski and John V. Pepper found that the apparent effects of RTC laws on crime rates depend significantly on the assumptions made in the analysis. A 2019 study found no statistically significant association between the liberalization of state level firearm carry legislation over the last 30 years and the rates of homicides or other violent crime.

Child Access Prevention (CAP)

Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws, enacted by many states, require parents to store firearms safely, to minimize access by children to guns, while maintaining ease of access by adults. CAP laws hold gun owners liable should a child gain access to a loaded gun that is not properly stored. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) claimed that, on average, one child died every three days in accidental incidents in the U.S. from 2000 to 2005. In most states, CAP law violations are considered misdemeanors. Florida's CAP law, enacted in 1989, permits felony prosecution of violators. Research indicates that CAP laws are correlated with a reduction in unintentional gun deaths by 23%, and gun suicides among those aged 14 through 17 by 11%. A study by Lott did not detect a relationship between CAP laws and accidental gun deaths or suicides among those age 19 and under between 1979 and 1996. However, two studies disputed Lott's findings. A 2013 study found that CAP laws are correlated with a reduction of non-fatal gun injuries among both children and adults by 30–40%. In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics found that safe gun storage laws were associated with lower overall adolescent suicide rates. Research also indicated that CAP laws were most highly correlated with reductions of non-fatal gun injuries in states where violations were considered felonies, whereas in states that considered violations as misdemeanors, the potential impact of CAP laws was not statistically significant.

Local restrictions

Some local jurisdictions in the U.S. have more restrictive laws, such as Washington, D.C.'s Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975, which banned residents from owning handguns, and required permitted firearms be disassembled and locked with a trigger lock. On March 9, 2007, a U.S. Appeals Court ruled the Washington, D.C. handgun ban unconstitutional. The appeal of that case later led to the Supreme Court's ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller that D.C.'s ban was unconstitutional under the Second Amendment.

Despite New York City's strict gun control laws, guns are often trafficked in from other parts of the U.S., particularly the southern states. Results from the ATF's Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative indicate that the percentage of imported guns involved in crimes is tied to the stringency of local firearm laws.

Prevention programs

Violence prevention and educational programs have been established in many schools and communities across the United States. These programs aim to change personal behavior of both children and their parents, encouraging children to stay away from guns, ensure parents store guns safely, and encourage children to solve disputes without resorting to violence. Programs aimed at altering behavior range from passive (requiring no effort on the part of the individual) to active (supervising children, or placing a trigger lock on a gun). The more effort required of people, the more difficult it is to implement a prevention strategy. Prevention strategies focused on modifying the situational environment and the firearm itself may be more effective. Empirical evaluation of gun violence prevention programs has been limited. Of the evaluations that have been done, results indicate such programs have minimal effectiveness.

Hotline

SPEAK UP is a national youth violence prevention initiative created by The Center to Prevent Youth Violence, which provides young people with tools to improve the safety of their schools and communities. The SPEAK UP program is an anonymous, national hot-line for young people to report threats of violence in their communities or at school. The hot-line is operated in accordance with a protocol developed in collaboration with national education and law enforcement authorities, including the FBI. Trained counselors, with access to translators for 140 languages, collect information from callers and then report the threat to appropriate school and law enforcement officials.

Gun safety parent counseling

One of the most widely used parent counseling programs is Steps to Prevent Firearm Injury program (STOP), which was developed in 1994 by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence (the latter of which was then known as the Center to Prevent Handgun Violence). STOP was superseded by STOP 2 in 1998, which has a broader focus including more communities and health care providers. STOP has been evaluated and found not to have a significant effect on gun ownership or firearm storage practices by inner-city parents. Marjorie S. Hardy suggests further evaluation of STOP is needed, as this evaluation had a limited sample size and lacked a control group. A 1999 study found no statistically significant effect of STOP on rates of gun ownership or better gun storage.

Children

Prevention programs geared towards children have also not been greatly successful. Many inherent challenges arise when working with children, including their tendency to perceive themselves as invulnerable to injury, limited ability to apply lessons learned, their innate curiosity, and peer pressure.

The goal of gun safety programs, usually administered by local firearms dealers and shooting clubs, is to teach older children and adolescents how to handle firearms safely. There has been no systematic evaluation of the effect of these programs on children. For adults, no positive effect on gun storage practices has been found as a result of these programs. Also, researchers have found that gun safety programs for children may likely increase a child's interest in obtaining and using guns, which they cannot be expected to use safely all the time, even with training.

One approach taken is gun avoidance, such as when encountering a firearm at a neighbor's home. The Eddie Eagle Gun Safety Program, administered by the National Rifle Association (NRA), is geared towards younger children from pre-kindergarten to sixth grade, and teaches kids that real guns are not toys by emphasizing a "just say no" approach. The Eddie Eagle program is based on training children in a four-step action to take when they see a firearm: (1) Stop! (2) Don't touch! (3) Leave the area. (4) Go tell an adult. Materials, such as coloring books and posters, back the lessons up and provide the repetition necessary in any child-education program. ABC News challenged the effectiveness of the "just say no" approach promoted by the NRA's Eddie the Eagle program in an investigative piece by Diane Sawyer in 1999. Sawyer's piece was based on an academic study conducted by Dr. Marjorie Hardy. Dr. Hardy's study tracked the behavior of elementary age schoolchildren who spent a day learning the Eddie the Eagle four-step action plan from a uniformed police officer. The children were then placed into a playroom which contained a hidden gun. When the children found the gun, they did not run away from the gun, but rather, they inevitably played with it, pulled the trigger while looking into the barrel, or aimed the gun at a playmate and pulled the trigger. The study concluded that children's natural curiosity was far more powerful than the parental admonition to "Just say no".

Community programs

Programs targeted at entire communities, such as community revitalization, after-school programs, and media campaigns, may be more effective in reducing the general level of violence that children are exposed to. Community-based programs that have specifically targeted gun violence include Safe Kids/Healthy Neighborhoods Injury Prevention Program in New York City, and Safe Homes and Havens in Chicago. Evaluation of such community-based programs is difficult, due to many confounding factors and the multifaceted nature of such programs. A Chicago-based program, "BAM" (Becoming a Man) has produced positive results, according to the University of Chicago Crime Lab, and is expanding to Boston in 2017.

March for Our Lives

The March for Our Lives was a student-led demonstration in support of legislation to prevent gun violence in the United States. It took place in Washington, D.C. on March 24, 2018, with over 880 sibling events throughout the U.S.[279][280][281][282][283] It was planned by Never Again MSD in collaboration with the nonprofit organization.[284] The demonstration followed the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida on February 14, 2018, which was described by several media outlets as a possible tipping point for gun control legislation.

Intervention programs

Sociologist James D. Wright suggests that to convince inner-city youths not to carry guns "requires convincing them that they can survive in their neighborhood without being armed, that they can come and go in peace, that being unarmed will not cause them to be victimized, intimidated, or slain." Intervention programs, such as CeaseFire Chicago, Operation Ceasefire in Boston and Project Exile in Richmond, Virginia during the 1990s, have been shown to be effective. Other intervention strategies, such as gun "buy-back" programs have been demonstrated to be ineffective.

Gun buyback programs

Gun "buyback" programs are a strategy aimed at influencing the firearms market by taking guns "off the streets". Gun "buyback" programs have been shown to be effective to prevent suicides, but ineffective to prevent homicides with the National Academy of Sciences citing theory underlying these programs as "badly flawed." Guns surrendered tend to be those least likely to be involved in crime, such as old, malfunctioning guns with little resale value, muzzleloading or other black-powder guns, antiques chambered for obsolete cartridges that are no longer commercially manufactured or sold, or guns that individuals inherit but have little value in possessing. Other limitations of gun buyback programs include the fact that it is relatively easy to obtain gun replacements, often of better guns than were relinquished in the buyback. Also, the number of handguns used in crime (about 7,500 per year) is very small compared to about 70 million handguns in the U.S.. (i.e., 0.011%).[289]

"Gun bounty" programs launched in several Florida cities have shown more promise. These programs involve cash rewards for anonymous tips about illegal weapons that lead to an arrest and a weapons charge. Since its inception in May 2007, the Miami program has led to 264 arrests and the confiscation of 432 guns owned illegally and $2.2 million in drugs, and has solved several murder and burglary cases.

Operation Ceasefire

In 1995, Operation Ceasefire was established as a strategy for addressing youth gun violence in Boston. Violence was particularly concentrated in poor, inner-city neighborhoods including Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan. There were 22 youths (under the age of 24) killed in Boston in 1987, with that figure rising to 73 in 1990. Operation Ceasefire entailed a problem-oriented policing approach, and focused on specific places that were crime hot spots—two strategies that when combined have been shown to be quite effective. Particular focus was placed on two elements of the gun violence problem, including illicit gun trafficking and gang violence. Within two years of implementing Operation Ceasefire in Boston, the number of youth homicides dropped to ten, with only one handgun-related youth homicide occurring in 1999 and 2000. The Operation Ceasefire strategy has since been replicated in other cities, including Los Angeles. Erica Bridgeford, spearheaded a "72-hour ceasefire" in August 2017, but the ceasefire was broken with a homicide. Councilman Brandon Scott, Mayor Catherine Pugh and others talked of community policing models that might work for Baltimore.

Project Exile

Project Exile, conducted in Richmond, Virginia during the 1990s, was a coordinated effort involving federal, state, and local officials that targeted gun violence. The strategy entailed prosecution of gun violations in Federal courts, where sentencing guidelines were tougher. Project Exile also involved outreach and education efforts through media campaigns, getting the message out about the crackdown. Research analysts offered different opinions as to the program's success in reducing gun crime. Authors of a 2003 analysis of the program argued that the decline in gun homicide was part of a "general regression to the mean" across U.S. cities with high homicide rates. Authors of a 2005 study disagreed, concluding that Richmond's gun homicide rate fell more rapidly than the rates in other large U.S. cities with other influences controlled.

Project Safe Neighborhoods

Project Safe Neighborhoods (PSN) is a national strategy for reducing gun violence that builds on the strategies implemented in Operation Ceasefire and Project Exile. PSN was established in 2001, with support from the Bush administration, channelled through the United States Attorney's Offices in the United States Department of Justice. The Federal government has spent over US$1.5 billion since the program's inception on the hiring of prosecutors, and providing assistance to state and local jurisdictions in support of training and community outreach efforts.

READI Chicago

In 2016, Chicago saw a 58% increase in homicides. In response to the spike in gun violence, a group of foundations and social service agencies created the Rapid Employment and Development Initiative (READI) Chicago. A Heartland Alliance program, READI Chicago targets those most at risk of being involved in gun violence – either as perpetrator or a victim. Individuals are provided with 18 months of transitional jobs, cognitive behavioral therapy and legal and social services. Individuals are also provided with 6 months of support as they transition to full-time employment at the end of the 18 months. The University of Chicago Crime Lab is evaluating READI Chicago's impact on gun violence reduction. The evaluation, expected to be completed in Spring 2021, is showing early signs of success. Eddie Bocanegra, senior director of READI Chicago, hopes that the early success of READI Chicago will result in funding from the City of Chicago.

Reporting of crime

The National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) is used by law enforcement agencies in the United States for collecting and reporting data on crimes. The NIBRS is one of four subsets of the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program.

- Traditional Summary Reporting System (SRS) and the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) – Offense and arrest data

- Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program

- Hate Crime Statistics Program – hate crimes

- Cargo Theft Reporting Program – cargo theft

The FBI states the UCR Program is retiring the SRS and will transition to a NIBRS-only data collection by January 1, 2021. Additionally, the FBI states NIBRS will collect more detailed information, including incident date and time, whether reported offenses were attempted or completed, expanded victim types, relationships of victims to offenders and offenses, demographic details, location data, property descriptions, drug types and quantities, the offender's suspected use of drugs or alcohol, the involvement of gang activity, and whether a computer was used in the commission of the crime.

Though NIBRS will be collecting more data the reporting if the firearm used was legally or illegally obtained by the suspect will not be identified. Nor will the system have the capability to identify if a legally obtained firearm used in the crime was used by the owner or registered owner, if required to be registered. Additionally, the information of how an illegally obtained firearm was acquired will be left to speculation. The absence of collecting this information into NIBRS the reported "gun violence" data will remain a gross misinterpretation lending anyone information that can be skewed to their liking/needs and not pinpoint where actual efforts need to be directed to curb the use of firearms in crime.

Research limitations

In the United States, research into firearms and violent crime is fraught with difficulties, associated with limited data on gun ownership and use, firearms markets, and aggregation of crime data. Research studies into gun violence have primarily taken one of two approaches: case-control studies and social ecology. Gun ownership is usually determined through surveys, proxy variables, and sometimes with production and import figures. In statistical analysis of homicides and other types of crime which are rare events, these data tend to have poisson distributions, which also presents methodological challenges to researchers. With data aggregation, it is difficult to make inferences about individual behavior. This problem, known as ecological fallacy, is not always handled properly by researchers; this leads some to jump to conclusions that their data do not necessarily support.

In 1996 the NRA lobbied Congressman Jay Dickey (R-Ark.) to include budget provisions that prohibited the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) from advocating or promoting gun control and that deleted $2.6 million from the CDC budget, the exact amount the CDC had spent on firearms research the previous year. The ban was later extended to all research funded by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). According to an article in Nature, this made gun research more difficult, reduced the number of studies, and discouraged researchers from even talking about gun violence at medical and scientific conferences. In 2013, after the December 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, President Barack Obama ordered the CDC to resume funding research on gun violence and prevention, and put $10 million in the 2014 budget request for it. However, the order had no practical effect, as the CDC refused to act without a specific appropriation to cover the research, and Congress repeatedly declined to allocate any funds. As a result, the CDC has not performed any such studies since 1996.