Numerous experiments which were performed on human test subjects in the United States are considered unethical, because they were illegally performed or they were performed without the knowledge, consent, or informed consent of the test subjects. Such tests were performed throughout American history, but most of them were performed during the 20th century. The experiments included the exposure of humans to many chemical and biological weapons (including infections with deadly or debilitating diseases), human radiation experiments, injections of toxic and radioactive chemicals, surgical experiments, interrogation and torture experiments, tests which involved mind-altering substances, and a wide variety of other experiments. Many of these tests were performed on children, the sick, and mentally disabled individuals, often under the guise of "medical treatment". In many of the studies, a large portion of the subjects were poor, racial minorities, or prisoners.

Many of these experiments violated US law. Some others were sponsored by government agencies or rogue elements thereof, including the Centers for Disease Control, the United States military, and the Central Intelligence Agency, or they were sponsored by private corporations which were involved in military activities. The human research programs were usually highly secretive and performed without the knowledge or authorization of Congress, and in many cases information about them was not released until many years after the studies had been performed.

The ethical, professional, and legal implications of this in the United States medical and scientific community were quite significant, and led to many institutions and policies that attempted to ensure that future human subject research in the United States would be ethical and legal. Public outrage in the late 20th century over the discovery of government experiments on human subjects led to numerous congressional investigations and hearings, including the Church Committee and Rockefeller Commission, both of 1975, and the 1994 Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments, among others.

Surgical experiments

Throughout the 1840s, J. Marion Sims, who is often referred to as "the father of gynecology", performed surgical experiments on enslaved African women, without anaesthesia. The women— one of whom was operated on 30 times— eventually died from infections resulting from the experiments. However, the period during which Sims operated on female slaves, between 1845 and 1849, was one during which the new practice of anesthesia was not universally accepted as safe and effective. In order to test one of his theories about the causes of trismus in infants, Sims performed experiments where he used a shoemaker's awl to move around the skull bones of the babies of enslaved women. It has been claimed that he addicted the women in his surgical experiments to morphine, only providing the drugs after surgery was already complete, in order to make them more compliant. A contrary view is presented by the gynecologic surgeon and anthropologist L.L. Wall: "Sims' use of postoperative opium appears to have been well supported by the therapeutic practices of his day, and the regimen that he used was enthusiastically supported by many contemporary surgeons."

In 1874, Mary Rafferty, an Irish servant woman, came to Dr. Roberts Bartholow of the Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio for treatment of a lesion on her head. The lesion was diagnosed as a cancerous ulcer and surgical treatments were attempted. Dr. Bartholow saw Rafferty's condition as terminal but felt there was a research opportunity. He inserted electrode needles into her exposed brain matter to gauge her responses. This was done with no intention of treating her. Although Rafferty came out of the coma caused by the experiment three days later, she died from a massive seizure the following day. Bartholow described his experiment as follows:

When the needle entered the brain substance, she complained of acute pain in the neck. In order to develop more decided reactions, the strength of the current was increased ... her countenance exhibited great distress, and she began to cry. Very soon, the left hand was extended as if in the act of taking hold of some object in front of her; the arm presently was agitated with clonic spasm; her eyes became fixed, with pupils widely dilated; lips were blue, and she frothed at the mouth; her breathing became stertorous; she lost consciousness and was violently convulsed on the left side. The convulsion lasted five minutes and was succeeded by a coma. She returned to consciousness in twenty minutes from the beginning of the attack, and complained of some weakness and vertigo.

— Dr. Bartholow's research report

In the subsequent autopsy, Bartholow noted that some brain damage had occurred due to the electrodes but that she had died due to the cancer. Bartholow was criticized by fellow physicians and the American Medical Association formally condemned his experiments as he had caused direct harm to the patient, not in an attempt to treat her but, solely to gain knowledge. Additional issues were raised with the consent obtained. Although she gave "cheerful assent" to the procedure, she was described as "feeble-minded" (which may have been in part due to effects of the tumor on her brain) and likely did not fully understand. Bartholow apologized for his actions and expressed regret that some knowledge had been gained "at the expense of some injury to the patient".

In 1896, Dr. Arthur Wentworth performed spinal taps on 29 young children, without the knowledge or consent of their parents, at Children's Hospital Boston (now Boston Children's Hospital) in Boston, Massachusetts to discover whether doing so would be harmful.

From 1913 to 1951, Dr. Leo Stanley, chief surgeon at the San Quentin Prison, performed a wide variety of experiments on hundreds of prisoners at San Quentin. Many of the experiments involved testicular implants, where Stanley would take the testicles out of executed prisoners and surgically implant them into living prisoners. In other experiments, he attempted to implant the testicles of rams, goats, and boars into living prisoners. Stanley also performed various eugenics experiments, and forced sterilizations on San Quentin prisoners. Stanley believed that his experiments would rejuvenate old men, control crime (which he believed had biological causes), and prevent the "unfit" from reproducing.

Pathogens, disease and biological warfare agents

Late 19th century

In the 1880s, in Hawaii, a Californian physician working at a hospital for lepers injected six girls under the age of 12 with syphilis.

In 1895, New York City pediatrician Henry Heiman intentionally infected two mentally disabled boys—one four-year-old and one sixteen-year-old—with gonorrhea as part of a medical experiment. A review of the medical literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries found more than 40 reports of experimental infections with gonorrheal culture, including some where gonorrheal organisms were applied to the eyes of sick children.

U.S. Army doctors in the Philippines infected five prisoners with bubonic plague and induced beriberi in 29 prisoners; four of the test subjects died as a result. In 1906, Professor Richard P. Strong of Harvard University intentionally infected 24 Filipino prisoners with cholera, which had somehow become contaminated with bubonic plague. He did this without the consent of the patients, and without informing them of what he was doing. All of the subjects became sick and 13 died.

Early 20th century

In 1908, three Philadelphia researchers infected dozens of children with tuberculin at St. Vincent Orphanage in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, causing permanent blindness in some of the children and painful lesions and inflammation of the eyes in many of the others. In the study, they refer to the children as "material used".

In 1909, Frank Crazier Knowles published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association describing how he had deliberately infected two children in an orphanage with Molluscum contagiosum—a virus that causes wart-like growths but usually disappears entirely—after an outbreak in the orphanage, in order to study the disease.

In 1911, Dr. Hideyo Noguchi of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in Manhattan, New York City injected 146 hospital patients (some of whom were children) with a syphilis extract. He was later sued by the parents of some of the child subjects, who allegedly contracted syphilis as a result of his experiments.

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment ("Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male") was a clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972 in Tuskegee, Alabama, by the U.S. Public Health Service. In the experiment, 399 impoverished black males who had syphilis were offered "treatment" by the researchers, who did not tell the test subjects that they had syphilis and did not give them treatment for the disease, but rather just studied them to chart the progress of the disease. By 1947, penicillin became available as treatment, but those running the study prevented study participants from receiving treatment elsewhere, lying to them about their true condition, so that they could observe the effects of syphilis on the human body. By the end of the study in 1972, only 74 of the test subjects were alive. 28 of the original 399 men had died of syphilis, 100 were dead of related complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children were born with congenital syphilis. The study was not shut down until 1972, when its existence was leaked to the press, forcing the researchers to stop in the face of a public outcry.

1940s

In 1941, at the University of Michigan, virologists Thomas Francis, Jonas Salk and other researchers deliberately infected patients at several Michigan mental institutions with the influenza virus by spraying the virus into their nasal passages. Francis Peyton Rous, based at the Rockefeller Institute and editor of the Journal of Experimental Medicine, wrote the following to Francis regarding the experiments:

It may save you much trouble if you publish your paper... elsewhere than in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. The Journal is under constant scrutiny by the anti-vivisectionists who would not hesitate to play up the fact that you used for your tests human beings of a state institution. That the tests were wholly justified goes without saying.

Rous closely monitored the articles he published since the 1930s, when revival of the anti-vivisectionist movement raised pressure against certain human experimentation.

In 1941 Dr. William C. Black inoculated a twelve-month-old baby with herpes who was "offered as a volunteer". He submitted his research to the Journal of Experimental Medicine which rejected the findings due to the ethically questionable research methods used in the study. Rous called the experiment "an abuse of power, an infringement of the rights of an individual, and not excusable because the illness which followed had implications for science." The study was later published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

The Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study was a controlled study of the effects of malaria on the prisoners of Stateville Penitentiary near Joliet, Illinois, beginning in the 1940s. The study was conducted by the Department of Medicine (now the Pritzker School of Medicine) at the University of Chicago in conjunction with the United States Army and the U.S. State Department. At the Nuremberg trials, Nazi doctors cited the precedent of the malaria experiments as part of their defense. The study continued at Stateville Penitentiary for 29 years. In related studies from 1944 to 1946, Dr. Alf Alving, a nephrologist and professor at the University of Chicago Medical School, purposely infected psychiatric patients at the Illinois State Hospital with malaria so that he could test experimental treatments on them.

In a 1946 to 1948 study in Guatemala, U.S. researchers used prostitutes to infect prison inmates, insane asylum patients, and Guatemalan soldiers with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases in order to test the effectiveness of penicillin in treating the STDs. They later tried infecting people with "direct inoculations made from syphilis bacteria poured into the men's penises and on forearms and faces that were slightly abraded . . . or in a few cases through spinal punctures". Approximately 700 people were infected as part of the study (including orphan children). The study was sponsored by the Public Health Service, the National Institutes of Health, the Pan American Health Sanitary Bureau (now the World Health Organization's Pan American Health Organization) and the Guatemalan government. The team was led by John Charles Cutler, who later participated in the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. Cutler chose to do the study in Guatemala because he would not have been permitted to do it in the United States. In 2010 when the research was revealed, the U.S. officially apologized to Guatemala for the studies. A lawsuit has been launched against Johns Hopkins University, Bristol-Myers Squibb and the Rockefeller Foundation for alleged involvement in the study.

1950s

In 1950, in order to conduct a simulation of a biological warfare attack, the U.S. Navy sprayed large quantities of the bacteria Serratia marcescens – considered harmless at the time – over the city of San Francisco during a project called Operation Sea-Spray. Numerous citizens contracted pneumonia-like illnesses, and at least one person died as a result. The family of the man who died sued the government for gross negligence, but a federal judge ruled in favor of the government in 1981. Serratia tests were continued until at least 1969.

Also in 1950, Dr. Joseph Stokes of the University of Pennsylvania deliberately infected 200 female prisoners with viral hepatitis.

From the 1950s to 1972, mentally disabled children at the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island, New York were intentionally infected with viral hepatitis, for research whose purpose was to help discover a vaccine. From 1963 to 1966, Saul Krugman of New York University promised the parents of mentally disabled children that their children would be enrolled into Willowbrook in exchange for signing a consent form for procedures that he claimed were "vaccinations." In reality, the procedures involved deliberately infecting children with viral hepatitis by feeding them an extract made from the feces of patients infected with the disease.

In 1952, Chester M. Southam, a Sloan-Kettering Institute researcher, injected live cancer cells, known as HeLa cells, into prisoners at the Ohio State Penitentiary and cancer patients. Also at Sloan-Kettering, 300 healthy women were injected with live cancer cells without being told. The doctors stated that they knew at the time that it might cause cancer.

In 1953, Dr. Frank Olson and several other colleagues were unknowingly dosed with LSD as part of a CIA experiment. Olson died nine days later after falling to his death from a hotel window under suspicious circumstances.

The San Francisco Chronicle, December 17, 1979, p. 5 reported a claim by the Church of Scientology that the CIA conducted an open-air biological warfare experiment in 1955 near Tampa, Florida and elsewhere in Florida with whooping cough bacteria. It was alleged that the experiment tripled the whooping cough infections in Florida to over one-thousand cases and caused whooping cough deaths in the state to increase from one to 12 over the previous year. This claim has been cited in a number of later sources, although these added no further supporting evidence.

During the 1950s the United States conducted a series of field tests using entomological weapons (EW). Operation Big Itch, in 1954, was designed to test munitions loaded with uninfected fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis). In May 1955 over 300,000 uninfected mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) were dropped over parts of the U.S. state of Georgia to determine if the air-dropped mosquitoes could survive to take meals from humans. The mosquito tests were known as Operation Big Buzz. The U.S. engaged in at least two other EW testing programs, Operation Drop Kick and Operation May Day.

1960s

In 1963, 22 elderly patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn, New York City were injected with live cancer cells by Chester M. Southam, who in 1952 had done the same to prisoners at the Ohio State Prison, in order to "discover the secret of how healthy bodies fight the invasion of malignant cells". The administration of the hospital attempted to cover the study up, but the New York medical licensing board ultimately placed Southam on probation for one year. Two years later, the American Cancer Society elected him as their vice president.

From 1963 to 1969 as part of Project Shipboard Hazard and Defense (SHAD), the U.S. Army performed tests which involved spraying several U.S. ships with various biological and chemical warfare agents, while thousands of U.S. military personnel were aboard the ships. The personnel were not notified of the tests, and were not given any protective clothing. Chemicals tested on the U.S. military personnel included the nerve gases VX and Sarin, toxic chemicals such as zinc cadmium sulfide and sulfur dioxide, and a variety of biological agents.

In 1966, the U.S. Army released Bacillus globigii into the tunnels of the New York City Subway system, as part of a field experiment called A Study of the Vulnerability of Subway Passengers in New York City to Covert Attack with Biological Agents. The Chicago subway system was also subject to a similar experiment by the Army.

Human radiation experiments

Researchers in the United States have performed thousands of human radiation experiments to determine the effects of atomic radiation and radioactive contamination on the human body, generally on people who were poor, sick, or powerless. Most of these tests were performed, funded, or supervised by the United States military, Atomic Energy Commission, or various other U.S. federal government agencies.

The experiments included a wide array of studies, involving things like feeding radioactive food to mentally disabled children or conscientious objectors, inserting radium rods into the noses of schoolchildren, deliberately releasing radioactive chemicals over U.S. and Canadian cities, measuring the health effects of radioactive fallout from nuclear bomb tests, injecting pregnant women and babies with radioactive chemicals, and irradiating the testicles of prison inmates, amongst other things.

Much information about these programs was classified and kept secret. In 1986 the United States House Committee on Energy and Commerce released a report entitled American Nuclear Guinea Pigs : Three Decades of Radiation Experiments on U.S. Citizens. In the 1990s Eileen Welsome's reports on radiation testing for The Albuquerque Tribune prompted the creation of the Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments by executive order of president Bill Clinton in order to monitor government tests; it published results in 1995. Welsome later wrote a book called The Plutonium Files.

Radioactive iodine experiments

In a 1949 operation called the "Green Run," the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) released iodine-131 and xenon-133 into the atmosphere near the Hanford site in Washington, which contaminated a 500,000-acre (2,000 km2) area containing three small towns.

In 1953, the AEC ran several studies at the University of Iowa on the health effects of radioactive iodine in newborns and pregnant women. In one study, researchers gave pregnant women between 100 to 200 microcuries (3.7 to 7.4 MBq) of iodine-131, in order to study the women's aborted embryos in an attempt to discover at what stage, and to what extent, radioactive iodine crosses the placental barrier. In another study, they gave 25 newborn babies (who were under 36 hours old and weighed from 5.5 to 8.5 pounds (2.5 to 3.9 kg)) iodine-131, either by oral administration or through an injection, so that they could measure the amount of iodine in their thyroid glands, as iodine would go to that gland.

In another AEC study, researchers at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine fed iodine-131 to 28 healthy infants through a gastric tube to test the concentration of iodine in the infants' thyroid glands.

In 1953, the AEC sponsored a study to discover if radioactive iodine affected premature babies differently from full-term babies. In the experiment, researchers from Harper Hospital in Detroit orally administered iodine-131 to 65 premature and full-term infants who weighed from 2.1 to 5.5 pounds (0.95 to 2.49 kg).

In Alaska, starting in August 1955, the AEC selected a total of 102 Eskimo natives and Athapascan Indians who would be used to study the effects of radioactive iodine on thyroid tissue, particularly in cold environments. Over a two year span, the test subjects were given doses of I-131 and samples of saliva, urine, blood, and thyroid tissue were collected from them. The purpose and risks of the radioactive iodine dosing, along with the collection of body fluid and tissue samples was not explained to the test subjects, and the AEC did not conduct any follow-up studies to monitor for long-term health effects.

From 1955 to 1960, Sonoma State Hospital in northern California served as a permanent drop-off location for mentally disabled children diagnosed with cerebral palsy or lesser disorders. The children subsequently underwent painful experimentation without adult consent. Many were given spinal taps "for which they received no direct benefit." Reporters of 60 Minutes learned that in these five years, the brain of every child with cerebral palsy who died at Sonoma State was removed and studied without parental consent. According to the CBS story, over 1,400 patients died at the clinic.

In an experiment in the 1960s, over 100 Alaskan citizens were continually exposed to radioactive iodine.

In 1962, the Hanford site again released I-131, stationing test subjects along its path to record its effect on them. The AEC also recruited Hanford volunteers to ingest milk contaminated with I-131 during this time.

Uranium experiments

-- April 17, 1947 Atomic Energy Commission memo from Colonel O.G. Haywood, Jr. to Dr. Fidler at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee

Between 1946 and 1947, researchers at the University of Rochester injected uranium-234 and uranium-235 in dosages ranging from 6.4 to 70.7 micrograms per kilogram of body weight into six people to study how much uranium their kidneys could tolerate before becoming damaged.

Between 1953 and 1957, at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. William Sweet injected eleven terminally ill, comatose and semi-comatose patients with uranium in an experiment to determine, among other things, its viability as a chemotherapy treatment against brain tumors, which all but one of the patients had (one being a misdiagnosis). Dr. Sweet, who died in 2001, maintained that consent had been obtained from the patients and next of kin.

Plutonium experiments

From April 10, 1945 to July 18, 1947, eighteen people were injected with plutonium as part of the Manhattan Project. Doses administered ranged from 95 to 5,900 nanocuries.

Albert Stevens, a man misdiagnosed with stomach cancer, received "treatment" for his "cancer" at the U.C. San Francisco Medical Center in 1945. Dr. Joseph Gilbert Hamilton, a Manhattan Project doctor in charge of the human experiments in California had Stevens injected with Pu-238 and Pu-239 without informed consent. Stevens never had cancer; a surgery to remove cancerous cells was highly successful in removing the benign tumor, and he lived for another 20 years with the injected plutonium. Since Stevens received the highly radioactive Pu-238, his accumulated dose over his remaining life was higher than anyone has ever received: 64 Sv (6400 rem). Neither Albert Stevens nor any of his relatives were told that he never had cancer; they were led to believe that the experimental "treatment" had worked. His cremated remains were surreptitiously acquired by Argonne National Laboratory Center for Human Radiobiology in 1975 without the consent of surviving relatives. Some of the ashes were transferred to the National Human Radiobiology Tissue Repository at Washington State University, which keeps the remains of people who died with radioisotopes in their body.

Three patients at Billings Hospital at the University of Chicago were injected with plutonium. In 1946, six employees of a Chicago metallurgical lab were given water that was contaminated with plutonium-239 so that researchers could study how plutonium is absorbed into the digestive tract.

An eighteen-year-old woman at an upstate New York hospital, expecting to be treated for a pituitary gland disorder, was injected with plutonium.

Experiments involving other radioactive materials

Immediately after World War II, researchers at Vanderbilt University gave 829 pregnant mothers in Tennessee what they were told were "vitamin drinks" that would improve the health of their babies. The mixtures contained radioactive iron and the researchers were determining how fast the radioisotope crossed into the placenta. At least three children are known to have died from the experiments, from cancers and leukemia. Four of the women's babies died from cancers as a result of the experiments, and the women experienced rashes, bruises, anemia, hair/tooth loss, and cancer.

From 1946 to 1953, at the Walter E. Fernald State School in Massachusetts, in an experiment sponsored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and the Quaker Oats corporation, 73 mentally disabled children were fed oatmeal containing radioactive calcium and other radioisotopes, in order to track "how nutrients were digested". The children were not told that they were being fed radioactive chemicals; they were told by hospital staff and researchers that they were joining a "science club".

The University of California Hospital in San Francisco exposed 29 patients, some with rheumatoid arthritis, to total body irradiation (100-300 rad dose) to obtain data for the military.

In the 1950s, researchers at the Medical College of Virginia performed experiments on severe burn victims, most of them poor and black, without their knowledge or consent, with funding from the Army and in collaboration with the AEC. In the experiments, the subjects were exposed to additional burning, experimental antibiotic treatment, and injections of radioactive isotopes. The amount of radioactive phosphorus-32 injected into some of the patients, 500 microcuries (19 MBq), was 50 times the "acceptable" dose for a healthy individual; for people with severe burns, this likely led to significantly increased death rates.

Between 1948 and 1954, funded by the federal government, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Hospital inserted radium rods into the noses of 582 Baltimore, Maryland schoolchildren as an alternative to adenoidectomy. Similar experiments were performed on over 7,000 U.S. Army and Navy personnel during World War II. Nasal radium irradiation became a standard medical treatment and was used in over two and a half million Americans.

In another study at the Walter E. Fernald State School, in 1956, researchers gave mentally disabled children radioactive calcium orally and intravenously. They also injected radioactive chemicals into malnourished babies and then collected cerebrospinal fluid for analysis from their brains and spines.

In 1961 and 1962, ten Utah State Prison inmates had blood samples taken which were mixed with radioactive chemicals and reinjected back into their bodies.

The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission funded the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to administer radium-224 and thorium-234 to 20 people between 1961 and 1965. Many were chosen from the Age Center of New England and had volunteered for "research projects on aging". Doses were 0.2–2.4 microcuries (7.4–88.8 kBq) for radium and 1.2–120 microcuries (44–4,440 kBq) for thorium.

In a 1967 study that was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, pregnant women were injected with radioactive cortisol to see if it would cross the placental barrier and affect the fetuses.

Fallout research

In 1957, atmospheric nuclear explosions in Nevada, which were part of Operation Plumbbob were later determined to have released enough radiation to have caused from 11,000 to 212,000 excess cases of thyroid cancer among U.S. citizens who were exposed to fallout from the explosions, leading to between 1,100 and 21,000 deaths.

Early in the Cold War, in studies known as Project GABRIEL and Project SUNSHINE, researchers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia tried to determine how much nuclear fallout would be required to make the Earth uninhabitable. They realized that atmospheric nuclear testing had provided them an opportunity to investigate this. Such tests had dispersed radioactive contamination worldwide, and examination of human bodies could reveal how readily it was taken up and hence how much damage it caused. Of particular interest was strontium-90 in the bones. Infants were the primary focus, as they would have had a full opportunity to absorb the new contaminants. As a result of this conclusion, researchers began a program to collect human bodies and bones from all over the world, with a particular focus on infants. The bones were cremated and the ashes analyzed for radioisotopes. This project was kept secret primarily because it would be a public relations disaster; as a result parents and family were not told what was being done with the body parts of their relatives. These studies should not be confused with the Baby Tooth Survey, which was undertaken during the same time period.

Irradiation experiments

Between 1960 and 1971, the Department of Defense funded non-consensual whole body radiation experiments on mostly poor and black cancer patients, who were not told what was being done to them. Patients were told that they were receiving a "treatment" that might cure their cancer, but the Pentagon was trying to determine the effects of high levels of radiation on the human body. One of the doctors involved in the experiments was worried about litigation by the patients. He referred to them only by their initials on the medical reports. He did this so that, in his words, "there will be no means by which the patients can ever connect themselves up with the report", in order to prevent "either adverse publicity or litigation".

From 1960 to 1971, Dr. Eugene Saenger, funded by the Defense Atomic Support Agency, performed whole body radiation experiments on more than 90 poor, black, advanced stage cancer patients with inoperable tumors at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center during the Cincinnati Radiation Experiments. He forged consent forms, and did not inform the patients of the risks of irradiation. The patients were given 100 or more rads (1 Gy) of whole-body radiation, which in many caused intense pain and vomiting. Critics have questioned the medical rationale for this study, and contend that the main purpose of the research was to study the acute effects of radiation exposure.

From 1963 to 1973, a leading endocrinologist, Dr. Carl Heller, irradiated the testicles of Oregon and Washington prisoners. In return for their participation, he gave them $5 a month, and $100 when they had to receive a vasectomy upon conclusion of the trial. The surgeon who sterilized the men said that it was necessary to "keep from contaminating the general population with radiation-induced mutants". Dr. Joseph Hamilton, one of the researchers who had worked with Heller on the experiments, said that the experiments "had a little of the Buchenwald touch".

In 1963, University of Washington researchers irradiated the testicles of 232 prisoners to determine the effects of radiation on testicular function. When these inmates later left prison and had children, at least four of them had offspring born with birth defects. The exact number is unknown because researchers never followed up on the status of the subjects.

Chemical experiments

Nonconsensual tests

From 1942 to 1944, the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service conducted experiments which exposed thousands of U.S. military personnel to mustard gas, in order to test the effectiveness of gas masks and protective clothing.

From 1950 through 1953, the U.S. Army conducted Operation LAC (Large Area Coverage), spraying chemicals over six cities in the United States and Canada, in order to test dispersal patterns of chemical weapons. Army records stated that the chemicals which were sprayed on the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, included zinc cadmium sulfide, which was not thought to be harmful. A 1997 study by the U.S. National Research Council found that it was sprayed at levels so low as not to be harmful; it said that people were normally exposed to higher levels in urban environments.

To test whether or not sulfuric acid, which is used in making molasses, was harmful as a food additive, the Louisiana State Board of Health commissioned a study to feed "Negro prisoners" nothing but molasses for five weeks. One report stated that prisoners didn't "object to submitting themselves to the test, because it would not do any good if they did."

A 1953 article in the medical/scientific journal Clinical Science described a medical experiment in which researchers intentionally blistered the skin on the abdomens of 41 children, who ranged in age from 8 to 14, using cantharide. The study was performed to determine how severely the substance injures/irritates the skin of children. After the studies, the children's blistered skin was removed with scissors and swabbed with peroxide.

Operation Top Hat

In June 1953, the United States Army formally adopted guidelines regarding the use of human subjects in chemical, biological, or radiological testing and research, where authorization from the Secretary of the Army was now required for all research projects involving human subjects. Under the guidelines, seven research projects involving chemical weapons and human subjects were submitted by the Chemical Corps for Secretary of the Army approval in August 1953. One project involved vesicants, one involved phosgene, and five were experiments which involved nerve agents; all seven were approved.

The guidelines, however, left a loophole; they did not define what types of experiments and tests required such approval from the Secretary. Operation Top Hat was among the numerous projects not submitted for approval. It was termed a "local field exercise" by the Army and took place from September 15–19, 1953 at the Army Chemical School at Fort McClellan, Alabama. The experiments used Chemical Corps personnel to test decontamination methods for biological and chemical weapons, including sulfur mustard and nerve agents. The personnel were deliberately exposed to these contaminants, were not volunteers, and were not informed of the tests. In a 1975 Pentagon Inspector General's report, the military maintained that Operation Top Hat was not subject to the guidelines requiring approval because it was a line of duty exercise in the Chemical Corps.

Holmesburg program

From approximately 1951 to 1974, the Holmesburg Prison in Pennsylvania was the site of extensive dermatological research operations, using prisoners as subjects. Led by Dr. Albert M. Kligman of the University of Pennsylvania, the studies were performed on behalf of Dow Chemical Company, the U.S. Army, and Johnson & Johnson. In one of the studies, for which Dow Chemical paid Kligman $10,000, Kligman injected dioxin — a highly toxic, carcinogenic compound which is found in Agent Orange, which Dow was manufacturing for use in Vietnam at the time — into 70 prisoners. The prisoners developed severe lesions which went untreated for seven months. Dow Chemical wanted to study the health effects of dioxin and other herbicides, in order to discover how they affect human skin, because workers at its chemical plants were developing chloracne. In the study, Kligman applied about the same amount of dioxin as that to which Dow employees were being exposed. In 1980 and 1981, some of the people who were used in this study sued Professor Kligman because they were suffering from a variety of health problems, including lupus and psychological damage.

Kligman later continued his dioxin studies, increasing the dosage of dioxin which he applied to the skin of 10 prisoners to 7,500 micrograms of dioxin, which is 468 times the dosage that the Dow Chemical official Gerald K. Rowe had authorized him to administer. As a result, the prisoners developed inflammatory pustules and papules.

The Holmesburg program paid hundreds of inmates a nominal stipend in order to test a wide range of cosmetic products and chemical compounds, whose health effects were unknown at the time. Upon his arrival at Holmesberg, Kligman is claimed to have said, "All I saw before me were acres of skin ... It was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time." A 1964 issue of Medical News reported that 9 out of 10 prisoners at Holmesburg Prison were medical test subjects.

In 1967, the U.S. Army paid Kligman to apply skin-blistering chemicals to the faces and backs of inmates at Holmesburg, in Kligman's words, "to learn how the skin protects itself against chronic assault from toxic chemicals, the so-called hardening process."

Psychological and torture experiments

U.S. government research

The United States government funded and performed numerous psychological experiments, especially during the Cold War era. Many of these experiments were performed to help develop more effective torture and interrogation techniques for the U.S. military and intelligence agencies, and to develop techniques for Americans to resist torture at the hands of enemy nations and organizations.

Truth serum

In studies running from 1947 to 1953, which were known as Project CHATTER, the U.S. Navy began identifying and testing truth serums, which they hoped could be used during interrogations of Soviet spies. Some of the chemicals tested on human subjects included mescaline and the anticholinergic drug scopolamine.

Shortly thereafter, in 1950, the CIA initiated Project BLUEBIRD, later renamed Project ARTICHOKE, whose stated purpose was to develop "the means to control individuals through special interrogation techniques", "way[s] to prevent the extraction of information from CIA agents", and "offensive uses of unconventional techniques, such as hypnosis and drugs". The purpose of the project was outlined in a memo dated January 1952 that stated, "Can we get control of an individual to the point where he will do our bidding against his will and even against fundamental laws of nature, such as self preservation?" The project studied the use of hypnosis, forced morphine addiction and subsequent forced withdrawal, and the use of other chemicals, among other methods, to produce amnesia and other vulnerable states in subjects. In order to "perfect techniques ... for the abstraction of information from individuals, whether willing or not", Project BLUEBIRD researchers experimented with a wide variety of psychoactive substances, including LSD, heroin, marijuana, cocaine, PCP, mescaline, and ether. Project BLUEBIRD researchers dosed over 7,000 U.S. military personnel with LSD, without their knowledge or consent, at the Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. Years after these experiments, more than 1,000 of these soldiers suffered from several illnesses, including depression and epilepsy. Many of them tried to commit suicide.

Drug deaths

In 1952, professional tennis player Harold Blauer died when he was injected with a fatal dose of a mescaline derivative at the New York State Psychiatric Institute of Columbia University by Dr. James McKeen Cattell. The United States Department of Defense, which sponsored the injection, worked in collusion with the Department of Justice and the New York State Attorney General to conceal evidence of its involvement in the experiment for 23 years. Cattell claimed that he did not know what the army had ordered him to inject into Blauer, saying: "We didn't know whether it was dog piss or what we were giving him."

On November 19, 1953, Dr. Frank Olson was given a dosage of LSD without his knowledge or consent. After falling from a hotel window nine days later, he died under suspicious circumstances. Until the Project MKUltra revelations, the cause of Dr. Olson's death was covered up for 22 years.

MKUltra

In 1953, the CIA placed several of its interrogation and mind-control programs under the direction of a single program, known by the code name MKULTRA, after CIA director Allen Dulles complained about not having enough "human guinea pigs to try these extraordinary techniques". The MKULTRA project was under the direct command of Dr. Sidney Gottlieb of the Technical Services Division. The project received over $25 million, and involved hundreds of experiments on human subjects at eighty different institutions.

In a memo describing the purpose of one MKULTRA program subprogram, Richard Helms said:

We intend to investigate the development of a chemical material which causes a reversible, nontoxic aberrant mental state, the specific nature of which can be reasonably well predicted for each individual. This material could potentially aid in discrediting individuals, eliciting information, and implanting suggestions and other forms of mental control.

— Richard Helms, internal CIA memo

In 1954, the CIA's Project QKHILLTOP was created to study Chinese brainwashing techniques, and to develop effective methods of interrogation. Most of the early studies are believed to have been performed by the Cornell University Medical School's human ecology study programs, under the direction of Dr. Harold Wolff. Wolff requested that the CIA provide him any information they could find regarding "threats, coercion, imprisonment, deprivation, humiliation, torture, 'brainwashing', 'black psychiatry', and hypnosis, or any combination of these, with or without chemical agents." According to Wolff, the research team would then:

...assemble, collate, analyze and assimilate this information and will then undertake experimental investigations designed to develop new techniques of offensive/defensive intelligence use ... Potentially useful secret drugs (and various brain damaging procedures) will be similarly tested in order to ascertain the fundamental effect upon human brain function and upon the subject's mood ... Where any of the studies involve potential harm of the subject, we expect the Agency to make available suitable subjects and a proper place for the performance of the necessary experiments.

— Dr. Harold Wolff, Cornell University Medical School

-- George Hunter White, who oversaw drug experiments for the CIA as part of Operation Midnight Climax

Another of the MKULTRA subprojects, Operation Midnight Climax, consisted of a web of CIA-run safehouses in San Francisco, Marin, and New York which were established in order to study the effects of LSD on unconsenting individuals. Prostitutes on the CIA payroll were instructed to lure clients back to the safehouses, where they were surreptitiously plied with a wide range of substances, including LSD, and monitored behind one-way glass. Several significant operational techniques were developed in this theater, including extensive research into sexual blackmail, surveillance technology, and the possible use of mind-altering drugs in field operations.

In 1957, with funding from a CIA front organization, Donald Ewen Cameron of the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal, Quebec, Canada began MKULTRA Subproject 68. His experiments were designed to first "depattern" individuals, erasing their minds and memories—reducing them to the mental level of an infant—and then to "rebuild" their personality in a manner of his choosing. To achieve this, Cameron placed patients under his "care" into drug-induced comas for up to 88 days, and applied numerous high voltage electric shocks to them over the course of weeks or months, often administering up to 360 shocks per person. He would then perform what he called "psychic driving" experiments on the subjects, where he would repetitively play recorded statements, such as "You are a good wife and mother and people enjoy your company", through speakers he had implanted into blacked-out football helmets that he bound to the heads of the test subjects (for sensory deprivation purposes). The patients could do nothing but listen to these messages, played for 16–20 hours a day, for weeks at a time. In one case, Cameron forced a person to listen to a message non-stop for 101 days. Using CIA funding, Cameron converted the horse stables behind Allan Memorial into an elaborate isolation and sensory deprivation chamber where he kept patients locked in for weeks at a time.

Cameron also induced insulin comas in his subjects by giving them large injections of insulin, twice a day, for up to two months at a time. Several of the children who Cameron experimented on were sexually abused, in at least one case by several men. One of the children was filmed numerous times performing sexual acts with high-ranking federal government officials, in a scheme set up by Cameron and other MKULTRA researchers, to blackmail the officials to ensure further funding for the experiments.

-- John D. Marks, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate, Chapter 8

Concerns

The CIA leadership had serious concerns about these activities, as evidenced in a 1957 Inspector General Report, which stated:

Precautions must be taken not only to protect operations from exposure to enemy forces but also to conceal these activities from the American public in general. The knowledge that the agency is engaging in unethical and illicit activities would have serious repercussions in political and diplomatic circles ...

— 1957 CIA Inspector General Report

In 1963, the CIA had synthesized many of the findings from its psychological research into what became known as the KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation handbook, which cited the MKULTRA studies and other secret research programs as the scientific basis for their interrogation methods. Cameron regularly traveled around the U.S. teaching military personnel about his techniques (hooding of prisoners for sensory deprivation, prolonged isolation, humiliation, etc.), and how they could be used in interrogations. Latin American paramilitary groups working for the CIA and U.S. military received training in these psychological techniques at places such as the School of the Americas. In the 21st century, many of the torture techniques developed in the MKULTRA studies and other programs were used at U.S. military and CIA prisons such as Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib. In the aftermath of the Congressional hearings, major news media mainly focused on sensationalistic stories related to LSD, "mind-control", and "brainwashing", and rarely used the word "torture". This suggested that the CIA researchers were, as one author put it, "a bunch of bumbling sci-fi buffoons", rather than a rational group of men who had run torture laboratories and medical experiments in major U.S. universities; they had arranged for torture, rape and psychological abuse of adults and young children, driving many of them permanently insane.

Shutdown

MKULTRA activities continued until 1973 when CIA director Richard Helms, fearing that they would be exposed to the public, ordered the project terminated, and all of the files destroyed. But, a clerical error had sent many of the documents to the wrong office, so when CIA workers were destroying the files, some of them remained. They were later released under a Freedom of Information Act request by investigative journalist John Marks. Many people in the American public were outraged when they learned of the experiments, and several congressional investigations took place, including the Church Committee and the Rockefeller Commission.

On April 26, 1976, the Church Committee of the United States Senate issued a report, Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operation with Respect to Intelligence Activities, In Book I, Chapter XVII, p. 389, this report states:

LSD was one of the materials tested in the MKULTRA program. The final phase of LSD testing involved surreptitious administration to unwitting non-volunteer subjects in normal life settings by undercover officers of the Bureau of Narcotics acting for the CIA.

A special procedure, designated MKDELTA, was established to govern the use of MKULTRA materials abroad. Such materials were used on a number of occasions. Because MKULTRA records were destroyed, it is impossible to reconstruct the operational use of MKULTRA materials by the CIA overseas; it has been determined that the use of these materials abroad began in 1953, and possibly as early as 1950.

Drugs were used primarily as an aid to interrogations, but MKULTRA/MKDELTA materials were also used for harassment, discrediting, or disabling purposes.

Experiments on patients with mental illness

Dr. Robert Heath of Tulane University performed experiments on 42 patients with schizophrenia and prisoners in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The experiments were funded by the U.S. Army. In the studies, he dosed them with LSD and bulbocapnine, and implanted electrodes into the septal area of the brain to stimulate it and take electroencephalography (EEG) readings.

Various experiments were performed on people with schizophrenia who were stable, other experiments were performed on people with their first episode of psychosis. They were given methylphenidate to see the effect on their minds.

Torture experiments

From 1964 to 1968, the U.S. Army paid $386,486 to professors Albert Kligman and Herbert W. Copelan to perform experiments with mind-altering drugs on 320 inmates of Holmesburg Prison. The goal of the study was to determine the minimum effective dose of each drug needed to disable 50 percent of any given population. Kligman and Copelan initially claimed that they were unaware of any long-term health effects the drugs could have on prisoners; however, documents later revealed that this was not the case.

Medical professionals gathered and collected data on the CIA's use of torture techniques on detainees during the 21st century war on terror, in order to refine those techniques, and "to provide legal cover for torture, as well as to help justify and shape future procedures and policies", according to a 2010 report by Physicians for Human Rights. The report stated that: "Research and medical experimentation on detainees was used to measure the effects of large-volume waterboarding and adjust the procedure according to the results." As a result of the waterboarding experiments, doctors recommended adding saline to the water "to prevent putting detainees in a coma or killing them through over-ingestion of large amounts of plain water." Sleep deprivation tests were performed on over a dozen prisoners, in 48-, 96- and 180-hour increments. Doctors also collected data intended to help them judge the emotional and physical effects of the techniques so as to "calibrate the level of pain experienced by detainees during interrogation" and to determine if using certain types of techniques would increase a subject's "susceptibility to severe pain." In 2010 the CIA denied the allegations, claiming they never performed any experiments, and saying "The report is just wrong"; however, the U.S. government never investigated the claims. Psychologists James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen ran a company that was paid $81 million by the CIA, that, according to the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture, developed the "enhanced interrogation techniques" used. In November 2014, the American Psychological Association announced that they would hire a lawyer to investigate claims that they were complicit in the development of enhanced interrogation techniques that constituted torture.

In August 2010, the U.S. weapons manufacturer Raytheon announced that it had partnered with a jail in Castaic, California in order to use prisoners as test subjects for its Active Denial System that "fires an invisible heat beam capable of causing unbearable pain." The device, dubbed "pain ray" by its critics, was rejected for fielding in Iraq due to Pentagon fears that it would be used as an instrument of torture.

Academic research

In 1939, at the Iowa Soldiers' Orphans' Home in Davenport, Iowa, twenty-two children were the subjects of the so-called "monster" experiment. This experiment attempted to use psychological abuse to induce stuttering in children who spoke normally. The experiment was designed by Dr. Wendell Johnson, one of the nation's most prominent speech pathologists, for the purpose of testing one of his theories on the cause of stuttering.

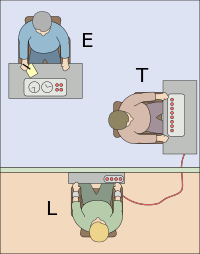

In 1961, in response to the Nuremberg Trials, the Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram performed his "Obedience to Authority Study", also known as the Milgram Experiment, in order to determine if it was possible that the Nazi genocide could have resulted from millions of people who were "just following orders". The Milgram Experiment raised questions about the ethics of scientific experimentation because of the extreme emotional stress suffered by the participants, who were told, as part of the experiment, to apply electric shocks to test subjects (who were actors and did not really receive electric shocks).

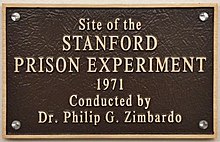

In 1971, Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo conducted the Stanford prison experiment in which twenty-four male students were randomly assigned roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison situated in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. The participants adapted to their roles beyond Zimbardo's expectations with prison guards exhibiting authoritarian status and psychologically abusing the prisoners who were passive in their acceptance of the abuse. The experiment was largely controversial with criticisms aimed toward the lack of scientific principles and a control group, and for ethical concerns regarding Zimbardo's lack of intervention in the prisoner abuse.

Pharmacological research

At Harvard University, in the late 1940s, researchers began performing experiments in which they tested diethylstilbestrol, a synthetic estrogen, on pregnant women at the Lying-In Hospital of the University of Chicago. The women experienced an abnormally high number of miscarriages and babies with low birth weight (LBW). None of the women were told that they were being experimented on.

In 1962, researchers at the Laurel Children's Center in Maryland tested experimental acne medications on children. They continued their tests even after half of the children developed severe liver damage from the medications.

In 2004, University of Minnesota research participant Dan Markingson committed suicide while enrolled in an industry-sponsored pharmaceutical trial comparing three FDA-approved atypical antipsychotics: Seroquel (quetiapine), Zyprexa (olanzapine), and Risperdal (risperidone). Writing on the circumstances surrounding Markingson's death in the study, which was designed and funded by Seroquel manufacturer AstraZeneca, University of Minnesota Professor of Bioethics Carl Elliott noted that Markingson was enrolled in the study against the wishes of his mother, Mary Weiss, and that he was forced to choose between enrolling in the study or being involuntarily committed to a state mental institution. Further investigation revealed financial ties to AstraZeneca by Markingson's psychiatrist, Dr. Stephen C. Olson, oversights and biases in AstraZeneca's trial design, and the inadequacy of university Institutional Review Board (IRB) protections for research subjects. A 2005 FDA investigation cleared the university. Nonetheless, controversy around the case has continued. A Mother Jones article resulted in a group of university faculty members sending a public letter to the university Board of Regents urging an external investigation into Markingson's death.

Other experiments

The 1846 journals of Walter F. Jones of Petersburg, Virginia, describe how he poured boiling water onto the backs of naked slaves afflicted with typhoid pneumonia, at four-hour intervals, because he thought that this might "cure" the disease by "stimulating the capillaries".

From early 1940 until 1953, Lauretta Bender, a highly respected pediatric neuropsychiatrist who practiced at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, performed electroshock experiments on at least 100 children. The children's ages ranged from three to 12 years. Some reports indicate that she may have performed such experiments on more than 200. From 1942 to 1956, electroconvulsive treatment (ECT) was used on more than 500 children at Bellevue Hospital, including Bender's experiments; from 1956 to 1969, ECT was used at Creedmoor State Hospital Children's Service. Publicly, Bender claimed that the results of the "therapy" were positive, but in private memos, she expressed frustration over mental health issues caused by the treatments. Bender would sometimes shock children with schizophrenia (some less than three years old) twice per day, for 20 consecutive days. Several of the children became violent and suicidal as a result of the treatments.

In 1942, the Harvard University biochemist Edwin Joseph Cohn injected 64 Massachusetts prisoners with cow blood, as part of an experiment sponsored by the U.S. Navy.

In 1950, researchers at the Cleveland City Hospital ran experiments to study changes in cerebral blood flow: they injected people with spinal anesthesia, and inserted needles into their jugular veins and brachial arteries to extract large quantities of blood and, after massive blood loss which caused paralysis and fainting, measured their blood pressure. The experiment was often performed multiple times on the same subject.

In a series of studies which were published in the medical journal Pediatrics, researchers from the University of California Department of Pediatrics performed experiments on 113 newborns ranging in age from one hour to three days, in which they studied changes in blood pressure and blood flow. In one of the studies, researchers inserted a catheter through the babies' umbilical arteries and into their aortas, and then submerged their feet in ice water. In another of the studies, they strapped 50 newborn babies to a circumcision board, and turned them upside down so that all of their blood rushed into their heads.

The San Antonio Contraceptive Study was a clinical research study published in 1971 about the side effects of oral contraceptives. Women coming to a clinic in San Antonio, Texas, to prevent pregnancies were not told they were participating in a research study or receiving placebos. Ten of the women became pregnant while on placebos.

During the decade of 2000–2010, artificial blood was transfused into research subjects across the United States without their consent by Northfield Labs. Later studies showed the artificial blood caused a significant increase in the risk of heart attacks and death.

Legal, academic and professional policy

During the Nuremberg Medical Trials, several of the Nazi doctors and scientists who were being tried for their human experiments cited past unethical studies performed in the United States in their defense, namely the Chicago malaria experiments conducted by Dr. Joseph Goldberger. Subsequent investigation led to a report by Andrew Conway Ivy, who testified that the research was "an example of human experiments which were ideal because of their conformity with the highest ethical standards of human experimentation". The trials contributed to the formation of the Nuremberg Code in an effort to prevent such abuses.

A secret AEC document dated April 17, 1947, titled Medical Experiments in Humans stated: "It is desired that no document be released which refers to experiments with humans that might have an adverse reaction on public opinion or result in legal suits. Documents covering such fieldwork should be classified Secret."

At the same time, the Public Health Service was instructed to tell citizens downwind from bomb tests that the increases in cancers were due to neurosis, and that women with radiation sickness, hair loss, and burned skin were suffering from "housewife syndrome".

In 1964, the World Medical Association passed the Declaration of Helsinki, a set of ethical principles for the medical community regarding human experimentation.

In 1966, the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office for Protection of Research Subjects (OPRR) was created. It issued its Policies for the Protection of Human Subjects, which recommended establishing independent review bodies to oversee experiments. These were later called institutional review boards.

In 1969, Kentucky Court of Appeals Judge Samuel Steinfeld dissented in Strunk v. Strunk, 445 S.W.2d 145. He made the first judicial suggestion that the Nuremberg Code should be applied to American jurisprudence.

In 1974 the National Research Act established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects. It mandated that the Public Health Service come up with regulations to protect the rights of human research subjects.

Project MKULTRA was first brought to wide public attention in 1975 by the U.S. Congress, through investigations by the Church Committee, and by a presidential commission known as the Rockefeller Commission.

In 1975, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (DHEW) created regulations which included the recommendations laid out in the NIH's 1966 Policies for the Protection of Human Subjects. Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, known as "The Common Rule," requires the appointment and use of institutional review boards (IRBs) in experiments using human subjects.

On April 18, 1979, prompted by an investigative journalist's public disclosure of the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (later renamed to Health and Human Services) released a report entitled Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, written by Dan Harms. It laid out many modern guidelines for ethical medical research.

In 1987 the United States Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Stanley, 483 U.S. 669, that a U.S. serviceman who was given LSD without his consent, as part of military experiments, could not sue the U.S. Army for damages. Stanley was later awarded over $400,000 in 1996, two years after Congress passed a private claims bill in reaction to the case. Dissenting the original verdict in U.S. v. Stanley, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor stated:

No judicially crafted rule should insulate from liability the involuntary and unknowing human experimentation alleged to have occurred in this case. Indeed, as Justice Brennan observes, the United States played an instrumental role in the criminal prosecution of Nazi scientists who experimented with human subjects during the Second World War, and the standards that the Nuremberg Military Tribunals developed to judge the behavior of the defendants stated that the 'voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential ... to satisfy moral, ethical, and legal concepts.' If this principle is violated, the very least that society can do is to see that the victims are compensated, as best they can be, by the perpetrators.

On January 15, 1994, President Bill Clinton formed the Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE). This committee was created to investigate and report the use of human beings as test subjects in experiments involving the effects of ionizing radiation in federally funded research. The committee attempted to determine the causes of the experiments and reasons that the proper oversight did not exist. It made several recommendations to help prevent future occurrences of similar events.

As of 2007, not a single U.S. government researcher had been prosecuted for human experimentation. The preponderance of the victims of U.S. government experiments have not received compensation or, in many cases, acknowledgment of what was done to them.