From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Contributors

in the field of Spiritual Ecology contend there are spiritual elements

at the root of environmental issues. Those working in the arena of

Spiritual Ecology further suggest that there is a critical need to

recognize and address the spiritual dynamics at the root of

environmental degradation.

The field is largely emerging through three individual streams of

formal study and activity: science and academia, religion and

spirituality, and ecological sustainability.

Despite the disparate arenas of study and practice, the

principles of spiritual ecology are simple: In order to resolve such

environmental issues as depletion of species, global warming, and

over-consumption, humanity must examine and reassess our underlying

attitudes and beliefs about the earth, and our spiritual

responsibilities toward the planet. U.S. Advisor on climate change, James Gustave Speth, said: "I used to think that top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse

and climate change. I thought that thirty years of good science could

address these problems. I was wrong. The top environmental problems are

selfishness, greed and apathy, and to deal with these we need a cultural

and spiritual transformation."

Thus, it is argued, ecological renewal and sustainability

necessarily depends upon spiritual awareness and an attitude of

responsibility. Spiritual Ecologists concur that this includes both the

recognition of creation as sacred and behaviors that honor that sacredness.

Recent written and spoken contributions of Pope Francis, particularly his May 2015 Encyclical, Laudato si', as well as unprecedented involvement of faith leaders at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris reflect a growing popularity of this emerging view. The UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon,

stated on December 4, 2015, that “Faith communities are vital for

global efforts to address the climate challenge. They remind us of the

moral dimensions of climate change, and of our obligation to care for

both the Earth’s fragile environment and our neighbours in need.”

History

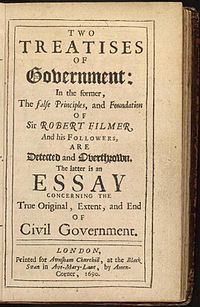

Spiritual ecology identifies the Scientific Revolution—beginning the 16th century, and continuing through the Age of Enlightenment to the Industrial Revolution—as

contributing to a critical shift in human understanding with

reverberating effects on the environment. The radical expansion of

collective consciousness into the era of rational science included a

collective change from experiencing nature as a living, spiritual

presence to a utilitarian means to an end.

During the modern age, reason

became valued over faith, tradition, and revelation. Industrialized

society replaced agricultural societies and the old ways of relating to

seasons and cycles. Furthermore, it is argued that the growing

predominance of a global, mechanized worldview, a collective sense of

the sacred was severed and replaced with an insatiable drive for scientific progress and material prosperity without any sense of limits or responsibility.

Some in Spiritual Ecology argue that a pervasive patriarchal world-view, and a monotheistic

religious orientation towards a transcendent divinity, is largely

responsible for destructive attitudes about the earth, body, and the

sacred nature of creation. Thus, many identify the wisdom of indigenous cultures, for whom the physical world is still regarded as sacred, as holding a key to our current ecological predicament.

Spiritual ecology is a response to the values and socio-political

structures of recent centuries with their trajectory away from intimacy

with the earth and its sacred essence. It has been forming and

developing as an intellectual and practice-oriented discipline for

nearly a century.

Spiritual ecology includes a vast array of people and practices

that intertwine spiritual and environmental experience and

understanding. Additionally, within the tradition itself resides a deep,

developing spiritual vision of a collective human/earth/divine

evolution that is expanding consciousness beyond the dualities of

human/earth, heaven/earth, mind/body. This belongs to the contemporary

movement that recognizes the unity and interrelationship, or

"interbeing," the interconnectedness of all of creation.

Visionaries carrying this thread include Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) who founded the spiritual movement of anthroposophy, and described a "co-evolution of spirituality and nature" and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin,

a French Jesuit and paleontologist (1881-1955) who spoke of a

transition in collective awareness toward a consciousness of the divinity

within every particle of life, even the most dense mineral. This shift

includes the necessary dissolution of divisions between fields of study

as mentioned above. "Science, philosophy and religion are bound to

converge as they draw nearer to the whole."

Thomas Berry, the American Passionist

priest known a 'geologian' (1914-2009), has been one of the most

influential figures in this developing movement, with his stress on

returning to a sense of wonder and reverence for the natural world. He

shared and furthered many of Teilhard de Chardin’s

views, including the understanding that humanity is not at the center

of the universe, but integrated into a divine whole with its own

evolutionary path. This view compels a re-thinking of the earth/human

relationship: "The present urgency is to begin thinking within the

context of the whole planet, the integral earth community with all its

human and other-than-human components."

More recently, leaders in the Engaged Buddhism movement, including Thich Nhat Hanh, also identify a need to return to a sense of self which includes the Earth. Joanna Macy describes a collective shift – referred to as the "Great Turning" – taking us into a new consciousness in which the earth is not experienced as separate. Sufi teacher Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee

similarly grounds his spiritual ecology work in the context of a

collective evolutionary expansion towards oneness, bringing us all

toward an experience of earth and humanity – all life – as

interdependent. In the vision and experience of oneness, the term

"spiritual ecology" becomes, itself, redundant. What is earth-sustaining

is spiritual; that which is spiritual honors a sacred earth.

An important element in the work of these contemporary teachers

is the call for humanity's full acceptance of responsibility for what we

have done – physically and spiritually – to the earth. Only through

accepting responsibility will healing and transformation occur.

Including the need for a spiritual response to the environmental crisis, Charles, Prince of Wales in his 2010 book Harmony: A New Way of Looking at Our World, writes: "A specifically mechanistic

science has only recently assumed a position of such authority in the

world... (and) not only has it prevented us from considering the world

philosophically any more, our predominantly mechanistic way of looking

at the world has also excluded our spiritual relationship with Nature.

Any such concerns get short shrift in the mainstream debate about what

we do to the Earth." Prince Charles, who has promoted environmental awareness since the 1980s,

continues: "... by continuing to deny ourselves this profound, ancient,

intimate relationship with Nature, I fear we are compounding our

subconscious sense of alienation and disintegration, which is mirrored

in the fragmentation and disruption of harmony we are bringing about in

the world around us. At the moment we are disrupting the teeming

diversity of life and the ‘ecosystems’ that sustain it—the forests and

prairies, the woodland, moorland and fens, the oceans, rivers and

streams. And this all adds up to the degree of ‘disease’ we are causing

to the intricate balance that regulates the planet's climate, on which

we so intimately depend."

In May 2015 Pope Francis’s Encyclical, “Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home,”

endorsed the need for a spiritual and moral response to our

environmental crisis, and thus implicitly brings the subject of

spiritual ecology to the forefront of our present ecological debate.

This encyclical recognizes that “The ecological crisis is essentially a spiritual problem,” in line with the ideas of this developing field. American environmentalist, author, and journalist Bill McKibben who has written extensively on the impact of global warming, says that Pope Francis has "brought the full weight of the spiritual order to bear on the global threat posed by climate change, and in so doing joined its power with the scientific order."

Scientist, environmentalist, and a leader in sustainable ecology David Suzuki

also expresses the importance of including the sacred in addressing the

ecological crisis: "The way we see the world shapes the way we treat

it. If a mountain is a deity, not a pile of ore; if a river is one of

the veins of the land, not potential irrigation water; if a forest is a

sacred grove, not timber; if other species are biological kin, not

resources; or if the planet is our mother, not an opportunity—then we

will treat each other with greater respect. Thus is the challenge, to look at the world from a different perspective."

Historically we see the development of the foundational ideas and

perspective of spiritual ecology in mystical arms of traditional

religions and spiritual arms of environmental conservation. These ideas

put forth a story of an evolving universe and potential human experience

of wholeness in which dualities dissipate—dualities that have marked

past eras and contributed to the destruction of the earth as "other"

than spirit.

A Catholic nun interviewed by Sarah MacFarland Taylor, author of the 2009 book, “Green Sisters: Spiritual Ecology” (Harvard University Press, 2009), articulates this perspective of unity: “There is no division between planting new fields and prayer.”

Indigenous wisdom

Many in the field of spiritual ecology agree that a distinct stream

of experience threading throughout history that has at its heart a lived

understanding of the principles, values and attitudes of spiritual

ecology: indigenous wisdom. The term "indigenous" in this context refers

to that which is native, original, and resident to a place, more

specifically to societies who share and preserve ways of knowing the

world in relationship to the land. For many Native traditions, the earth is the central spiritual context. This principle condition reflects an attitude and way of being in the world that is rooted in land and embedded in place.

Spiritual ecology directs us to look to revered holders of these

traditions in order to understand the source of our current ecological

and spiritual crisis and find guidance to move into a state of balance.

Features of many indigenous teachings include life as a continual act of prayer and thanksgiving,

knowledge and symbiotic relationship with an animate nature, and being

aware of one's actions on future generations. Such understanding

necessarily implies a mutuality and reciprocity between people, earth

and the cosmos.

The above historical trajectory is located predominantly in a

Judeo-Christian European context, for it is within this context that

humanity experienced the loss of the sacred nature of creation, with its

devastating consequences. For example, with colonization, indigenous spiritual ecology was historically replaced by an imposed Western belief that land and the environment are commodities to be used and exploited, with exploitation of natural resources

in the name of socio-economic evolution. This perspective "... tended

to remove any spiritual value of the land, with regard only given for economic value, and this served to further distance communities from intimate relationships with their environments," often with "devastating consequences for indigenous people and nature around the world." Research on early prehistoric human activity in the Quaternary extinction event, shows overhunting megafauna well before European colonization in North America, South America and Australia.

While this might cast doubt upon the view of indigenous wisdom and the

sacred relationship to land and environment throughout the entirety of

human history, it this does not negate the more recent devastating

effects as referenced.

Along with the basic principles and behaviors advocated by

spiritual ecology, some indigenous traditions hold the same evolutionary

view articulated by the Western spiritual teachers listed above. The

understanding of humanity evolving toward a state of unity and harmony

with the earth after a period of discord and suffering is described in a

number of prophecies around the globe. These include the White Buffalo

prophecy of the Plains Indians, the prophecy of the Eagle and Condor

from the people of the Andes, and the Onondaga prophecies held and

retold by Oren Lyons.

Current trends

Spiritual

ecology is developing largely in three arenas identified above: Science

and Academia, Religion and Spirituality, and Environmental

Conservation.

Science and academia

Among scholars contributing to spiritual ecology, five stand out: Steven Clark Rockefeller, Mary Evelyn Tucker, John Grim, Bron Taylor and Roger S. Gottlieb.

Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim are the co-ordinators of Yale University’s Forum on Religion and Ecology,

an international multi-religious project exploring religious

world-views, texts ethics and practices in order to broaden

understanding of the complex nature of current environmental concerns.

Steven C. Rockefeller is an author of numerous books about

religion and the environment, and is professor emeritus of religion at Middlebury College. He played a leading role in the drafting of the Earth Charter.

Roger S. Gottlieb is a professor of Philosophy at Worcester Polytechnic Institute

is author of over 100 articles and 16 books on environmentalism,

religious life, contemporary spirituality, political philosophy, ethics,

feminism, and the Holocaust.

Bron Taylor at the University of Florida coined the term "Dark

Green Religion" to describe a set of beliefs and practices centered on

the conviction that nature is sacred.

Other leaders in the field include: Leslie E. Sponsel at the University of Hawai'i, Sarah McFarland Taylor at Northwestern University, Mitchell Thomashow at Antioch University New England and the Schumacher College Programs.

Within the field of science, spiritual ecology is emerging in arenas including Physics, Biology (see: Ursula Goodenough), Consciousness Studies (see: Brian Swimme; California Institute of Integral Studies), Systems Theory (see: David Loy; Nondual Science Institute), and Gaia Hypothesis, which was first articulated by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis in the 1970s.

Another example is scientist and author Diana Beresford-Kroeger, world recognized expert on how trees chemically affect the environment, who brings together the fields of ethnobotany, horticulture, ecology,

and spirituality in relation to the current ecological crisis and

stewardship of the natural world. She says, "... the world, the gift of

this world is fantastic and phenomenal. The molecular working of the

world is extraordinary, the mathematics of the world is extraordinary...

sacred and science go together."

Religion and ecology

Within many faiths, environmentalism is becoming an area of study and advocacy. Pope Francis’s May 2015 encyclical, Laudato si',

offered a strong confirmation of spiritual ecology and its principles

from within the Catholic Church. Additionally, over 150 leaders from

various faiths signed a letter to the UN Climate Summit in Paris 2015, “Statement

of Faith and Spiritual Leaders on the upcoming United Nations Climate

Change Conference, COP21 in Paris in December 2015”, recognizing the

earth as “a gift” from God and calling for climate action. These

contemporary events are reflections of enduring themes coming to the

fore within many religions.

Christian environmentalists emphasize the ecological

responsibilities of all Christians as stewards of God's earth, while

contemporary Muslim religious ecology is inspired by Qur'anic themes,

such as mankind being khalifa,

or trustee of God on earth (2:30). There is also a Jewish ecological

perspective based upon the Bible and Torah, for example the laws of bal tashchit (neither to destroy wantonly, nor waste resources unnecessarily). Engaged Buddhism

applies Buddhist principles and teachings to social and environmental

issues. A collection of Buddhist responses to global warming can be seen

at Ecological Buddhism.

In addition to Pope Francis, other world traditions currently seem to include a subset of leaders committed to an ecological perspective. The "Green Patriarch," Bartholomew 1, the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church,

has worked since the late nineties to bring together scientists,

environmentalists, religious leaders and policy makers to address the

ecological crisis, and says protecting the planet is a "sacred task and a

common vocation… Global warming is a moral crisis and a moral

challenge.” The Islamic Foundation For Ecology And Environmental Sciences (IFEES)

were one of the sponsors of the International Islamic Climate Change

Symposium held in Istanbul in August 2015, which resulted in "Islamic

Declaration on Global Climate Change"—a declaration endorsed by

religious leaders, noted Islamic scholars and teachers from 20

countries.

In October, 2015, 425 rabbis signed "A Rabbinic Letter on the Climate

Crisis", calling for vigorous action to prevent worsening climate

disruption and to seek eco-social justice.

Hindu scriptures also allude strongly and often to the connection

between humans and nature, and these texts form the foundation of the

Hindu Declaration on Climate Change, presented at a 2009 meeting of the Parliament of World Religions.

Many world faith and religious leaders, such as the Dalai Lama, were

present at the 2015 Climate Change Conference, and shared the view that:

"Saving the planet is not just a political duty, but also a moral one." The Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje,

has also stated, "The environmental emergency that we face is not just a

scientific issue, nor is it just a political issue—it is also a moral

issue.”

These religious approaches to ecology also have a growing interfaith expression, for example in The Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development (ICSD) where world religious leaders speak out on climate change and sustainability. And at their gathering in Fall 2015, the Parliament of World Religions

created a declaration for Interfaith Action on Climate Change, and

"brought together more than 10,000 activists, professors, clergy, and

global leaders from 73 countries and 50 faiths to confront climate

change"

Earth-based traditions and earth spirituality

Care for and respect to earth as Sacred—as Mother Earth (Mother Nature)—who

provides life and nourishment, is a central point to Earth-based

spirituality. PaGaian Cosmology is a tradition within Earth-based

spirituality that focuses particularly in Spiritual Ecology and

celebrating the sacredness of life. Glenys Livingstone describes it in

her book as "an ecospirituality grounded in indigenous Western religious

celebration of the Earth-Sun annual cycle. By linking to story of the

unfolding universe this practice can be deepened. And a sense of the

Triple Goddess—central to the cycle and known in ancient cultures—may be

developed as a dynamic innate to all being. The ritual scripts and the

process of ritual events presented here, may be a journey into

self-knowledge through personal, communal and ecological story: the self

to be known is one that is integral with place."

Spirituality and ecology

While

religiously-oriented environmentalism is grounded in scripture and

theology, there is a more recent environmental movement that articulates

the need for an ecological approach founded on spiritual awareness

rather than religious belief. The individuals articulating this approach

may have a religious background, but their ecological vision comes from

their own lived spiritual experience.

The difference between this spiritually-oriented ecology and a

religious approach to ecology can be seen as analogous to how the Inter-spiritual Movement moves beyond interfaith and interreligious dialogue to focus on the actual experience of spiritual principles and practices.

Spiritual ecology similarly explores the importance of this

experiential spiritual dimension in relation to our present ecological

crisis.

The Engaged Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh speaks of the importance of mindfulness in taking care of our Mother Earth, and how the highest form of prayer is real communion with the Earth. Sandra Ingerman offers shamanic healing as a way of reversing pollution in Medicine for the Earth. Franciscan friar Richard Rohr emphasizes the need to experience the whole world as a divine incarnation. Sufi mystic Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee directs our attention not just to the suffering of the physical world, but also its interior spiritual self, or anima mundi

(world soul). Bill Plotkin and others are involved in the work of

finding within nature the reconnection with our soul and the world soul.

Cultural ecologist and geophilosopher David Abram, who coined the phrase "the more-than-human world" (in order to describe nature as a realm that thoroughly includes humankind with all our culture yet also necessarily exceeds

human creativity and culture) aims the careful language of his writing

and speaking toward a reenchantment of matter. He was the first

philosopher to call for an attentive reappraisal of "animism" as a

uniquely ecological way of perceiving, speaking, and thinking;

his writings are now associated with a broad movement, among both

academics and environmental activists, often termed the "new animism."

These are just a few of the diverse ways that practitioners of

spiritual ecology, within different spiritual traditions and

disciplines, bring our awareness back to the sacred nature of the

animate earth.

Environmental conservation

The environmental conservation field has been informed, shaped, and

led by individuals who have had profound experiences of nature's

sacredness and have fought to protect it. Recognizing the intimacy of

human soul and nature, many have pioneered a new way of thinking about

and relating to the earth.

Today many aspects of the environmental conservation movement are

empowered by spiritual principles and interdisciplinary cooperation.

Robin Wall Kimmerer,

Professor of Environmental and Forest Biology at the State University

of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, has recently

founded the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment which bridges scientific based study of ecology and the environment with traditional ecological knowledge, which includes spirituality. As she writes in this piece from Oxford Journal BioScience:

"Traditional ecological knowledge is increasingly being sought by

academics, agency scientists, and policymakers as a potential source of

ideas for emerging models of ecosystem management, conservation biology,

and ecological restoration. It has been recognized as complementary and

equivalent to scientific knowledge... Traditional ecological knowledge

is not unique to Native American culture but exists all over the world,

independent of ethnicity. It is born of long intimacy and attentiveness

to a homeland and can arise wherever people are materially and

spiritually integrated with their landscape."

In recent years, the World Wildlife Fund (World Wide Fund for Nature) has developed Sacred Earth: Faiths for Conservation,

a program to collaborate with spiritual leaders and faith communities

from all different spiritual traditions around the world, to face

environmental issues including deforestation, pollution, unsustainable

extraction, melting glaciers and rising sea levels. The Sacred Earth

program works with faith-based leaders and communities, who "best

articulate ethical and spiritual ideals around the sacred value of Earth and its diversity, and are committed to protecting it."

One of the conservation projects developed from the WWF Sacred Earth program is Khoryug,

based in the Eastern Himalayas, which is an association of several

Tibetan Buddhist monasteries that works on environmental protection of

the Himalayan region through apply the values of compassion and

interdependence towards the Earth and all living beings that dwell here.

Organized under the auspices of the 17th Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje,

the Khoryug project resulted in the publication of environmental

guidelines for Buddhists and "more than 55 monastery-led projects to

address forest degradation, water loss, wildlife trade, waste, pollution and climate change."

Krishna Kant Shukla,

a physicist and musician, is noted for his lectures on "Indian villages

as models of sustainable development" and his work in establishing Saha Astitva a model eco village and organic farm in tribal Maharashtra, India.

One trend to note is the recognition that women—by instinct and

nature—have a unique commitment and capacity to protect the earth's

resources. We see this illustrated in the lives of Wangari Maathai, founder of Africa's Green Belt Movement, which was initially made up of women planting trees; Jane Goodall, innovator of local sustainable programs in Africa, many of which are designed to empower girls and women; and Vandana Shiva, the Indian feminist activist working on a variety of issues including seed saving, protecting small farms in India and protesting agri-business.

Other contemporary inter-disciplinary environmentalists include Wendell Berry, a farmer, poet, and academic living in Kentucky, who fights for small farms and criticizes agri-business; and Satish Kumar, a former Jain monk and founder of Schumacher College, a center for ecological studies.

Opposing views

Although

the May 2015 Encyclical from Pope Francis brought the importance of the

subject spiritual ecology to the fore of mainstream contemporary

culture, it is a point of view that is not widely accepted or included

in the work of most environmentalists and ecologists. Academic research

on the subject has also generated some criticism.

Ken Wilber has criticized spiritual ecology, suggesting that “spiritually oriented deep ecologists”

fail to acknowledge the transcendent aspect of the divine, or

hierarchical cosmologies, and thus exclude an important aspect of

spirituality, as well as presenting what Wilber calls a one-dimensional

“flat land” ontology in which the sacred in nature is wholly immanent.

But Wilber's views are also criticized as not including an in-depth

understanding of indigenous spirituality