Human ecology is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. The philosophy and study of human ecology has a diffuse history with advancements in ecology, geography, sociology, psychology, anthropology, zoology, epidemiology, public health, and home economics, among others.

Historical development

The roots of ecology as a broader discipline can be traced to the Greeks and a lengthy list of developments in natural history science. Ecology also has notably developed in other cultures. Traditional knowledge, as it is called, includes the human propensity for intuitive knowledge, intelligent relations, understanding, and for passing on information about the natural world and the human experience. The term ecology was coined by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 and defined by direct reference to the economy of nature.

Like other contemporary researchers of his time, Haeckel adopted his terminology from Carl Linnaeus where human ecological connections were more evident. In his 1749 publication, Specimen academicum de oeconomia naturae, Linnaeus developed a science that included the economy and polis of nature. Polis stems from its Greek roots for a political community (originally based on the city-states), sharing its roots with the word police in reference to the promotion of growth and maintenance of good social order in a community. Linnaeus was also the first to write about the close affinity between humans and primates. Linnaeus presented early ideas found in modern aspects to human ecology, including the balance of nature while highlighting the importance of ecological functions (ecosystem services or natural capital in modern terms): "In exchange for performing its function satisfactorily, nature provided a species with the necessaries of life" The work of Linnaeus influenced Charles Darwin and other scientists of his time who used Linnaeus' terminology (i.e., the economy and polis of nature) with direct implications on matters of human affairs, ecology, and economics.

Ecology is not just biological, but a human science as well. An early and influential social scientist in the history of human ecology was Herbert Spencer. Spencer was influenced by and reciprocated his influence onto the works of Charles Darwin. Herbert Spencer coined the phrase "survival of the fittest", he was an early founder of sociology where he developed the idea of society as an organism, and he created an early precedent for the socio-ecological approach that was the subsequent aim and link between sociology and human ecology.

The history of human ecology has strong roots in geography and sociology departments of the late 19th century. In this context a major historical development or landmark that stimulated research into the ecological relations between humans and their urban environments was founded in George Perkins Marsh's book Man and Nature; or, physical geography as modified by human action, which was published in 1864. Marsh was interested in the active agency of human-nature interactions (an early precursor to urban ecology or human niche construction) in frequent reference to the economy of nature.

In 1894, an influential sociologist at the University of Chicago named Albion W. Small collaborated with sociologist George E. Vincent and published a ""laboratory guide" to studying people in their "every-day occupations."" This was a guidebook that trained students of sociology how they could study society in a way that a natural historian would study birds. Their publication "explicitly included the relation of the social world to the material environment."

The first English-language use of the term "ecology" is credited to American chemist and founder of the field of home economics, Ellen Swallow Richards. Richards first introduced the term as "oekology" in 1892, and subsequently developed the term "human ecology".

The term "human ecology" first appeared in Ellen Swallow Richards' 1907 Sanitation in Daily Life, where it was defined as "the study of the surroundings of human beings in the effects they produce on the lives of men". Richard's use of the term recognized humans as part of rather than separate from nature. The term made its first formal appearance in the field of sociology in the 1921 book "Introduction to the Science of Sociology", published by Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess (also from the sociology department at the University of Chicago). Their student, Roderick D. McKenzie helped solidify human ecology as a sub-discipline within the Chicago school. These authors emphasized the difference between human ecology and ecology in general by highlighting cultural evolution in human societies.

Human ecology has a fragmented academic history with developments spread throughout a range of disciplines, including: home economics, geography, anthropology, sociology, zoology, and psychology. Some authors have argued that geography is human ecology. Much historical debate has hinged on the placement of humanity as part or as separate from nature. In light of the branching debate of what constitutes human ecology, recent interdisciplinary researchers have sought a unifying scientific field they have titled coupled human and natural systems that "builds on but moves beyond previous work (e.g., human ecology, ecological anthropology, environmental geography)." Other fields or branches related to the historical development of human ecology as a discipline include cultural ecology, urban ecology, environmental sociology, and anthropological ecology. Even though the term ‘human ecology’ was popularized in the 1920s and 1930s, studies in this field had been conducted since the early nineteenth century in England and France.

Biological ecologists have traditionally been reluctant to study human ecology, gravitating instead to the allure of wild nature. Human ecology has a history of focusing attention on humans’ impact on the biotic world. Paul Sears was an early proponent of applying human ecology, addressing topics aimed at the population explosion of humanity, global resource limits, pollution, and published a comprehensive account on human ecology as a discipline in 1954. He saw the vast "explosion" of problems humans were creating for the environment and reminded us that "what is important is the work to be done rather than the label." "When we as a profession learn to diagnose the total landscape, not only as the basis of our culture, but as an expression of it, and to share our special knowledge as widely as we can, we need not fear that our work will be ignored or that our efforts will be unappreciated." Recently, the Ecological Society of America has added a Section on Human Ecology, indicating the increasing openness of biological ecologists to engage with human dominated systems and the acknowledgement that most contemporary ecosystems have been influenced by human action.

Overview

Human ecology has been defined as a type of analysis applied to the relations in human beings that was traditionally applied to plants and animals in ecology. Toward this aim, human ecologists (which can include sociologists) integrate diverse perspectives from a broad spectrum of disciplines covering "wider points of view". In its 1972 premier edition, the editors of Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal gave an introductory statement on the scope of topics in human ecology. Their statement provides a broad overview on the interdisciplinary nature of the topic:

- Genetic, physiological, and social adaptation to the environment and to environmental change;

- The role of social, cultural, and psychological factors in the maintenance or disruption of ecosystems;

- Effects of population density on health, social organization, or environmental quality;

- New adaptive problems in urban environments;

- Interrelations of technological and environmental changes;

- The development of unifying principles in the study of biological and cultural adaptation;

- The genesis of maladaptions in human biological and cultural evolution;

- The relation of food quality and quantity to physical and intellectual performance and to demographic change;

- The application of computers, remote sensing devices, and other new tools and techniques

Forty years later in the same journal, Daniel G. Bates (2012) notes lines of continuity in the discipline and the way it has changed:

Today there is greater emphasis on the problems facing individuals and how actors deal with them with the consequence that there is much more attention to decision-making at the individual level as people strategize and optimize risk, costs and benefits within specific contexts. Rather than attempting to formulate a cultural ecology or even a specifically “human ecology” model, researchers more often draw on demographic, economic and evolutionary theory as well as upon models derived from field ecology.

While theoretical discussions continue, research published in Human Ecology Review suggests that recent discourse has shifted toward applying principles of human ecology. Some of these applications focus instead on addressing problems that cross disciplinary boundaries or transcend those boundaries altogether. Scholarship has increasingly tended away from Gerald L. Young's idea of a "unified theory" of human ecological knowledge—that human ecology may emerge as its own discipline—and more toward the pluralism best espoused by Paul Shepard: that human ecology is healthiest when "running out in all directions.". But human ecology is neither anti-discipline nor anti-theory, rather it is the ongoing attempt to formulate, synthesize, and apply theory to bridge the widening schism between man and nature. This new human ecology emphasizes complexity over reductionism, focuses on changes over stable states, and expands ecological concepts beyond plants and animals to include people.

Application to epidemiology and public health

The application of ecological concepts to epidemiology has similar roots to those of other disciplinary applications, with Carl Linnaeus having played a seminal role. However, the term appears to have come into common use in the medical and public health literature in the mid-twentieth century. This was strengthened in 1971 by the publication of Epidemiology as Medical Ecology, and again in 1987 by the publication of a textbook on Public Health and Human Ecology. An “ecosystem health” perspective has emerged as a thematic movement, integrating research and practice from such fields as environmental management, public health, biodiversity, and economic development. Drawing in turn from the application of concepts such as the social-ecological model of health, human ecology has converged with the mainstream of global public health literature.

Connection to home economics

In addition to its links to other disciplines, human ecology has a strong historical linkage to the field of home economics through the work of Ellen Swallow Richards, among others. However, as early as the 1960s, a number of universities began to rename home economics departments, schools, and colleges as human ecology programs. In part, this name change was a response to perceived difficulties with the term home economics in a modernizing society, and reflects a recognition of human ecology as one of the initial choices for the discipline which was to become home economics. Current human ecology programs include the University of Wisconsin School of Human Ecology, the Cornell University College of Human Ecology, and the University of Alberta's Department of Human Ecology, among others.

Niche of the Anthropocene

Changes to the Earth by human activities have been so great that a new geological epoch named the Anthropocene has been proposed. The human niche or ecological polis of human society, as it was known historically, has created entirely new arrangements of ecosystems as we convert matter into technology. Human ecology has created anthropogenic biomes (called anthromes). The habitats within these anthromes reach out through our road networks to create what has been called technoecosystems containing technosols. Technodiversity exists within these technoecosystems. In direct parallel to the concept of the ecosphere, human civilization has also created a technosphere. The way that the human species engineers or constructs technodiversity into the environment, threads back into the processes of cultural and biological evolution, including the human economy.

Ecosystem services

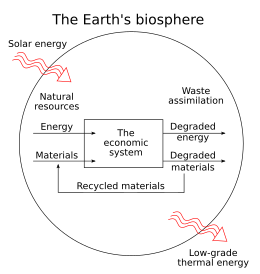

The ecosystems of planet Earth are coupled to human environments. Ecosystems regulate the global geophysical cycles of energy, climate, soil nutrients, and water that in turn support and grow natural capital (including the environmental, physiological, cognitive, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of life). Ultimately, every manufactured product in human environments comes from natural systems. Ecosystems are considered common-pool resources because ecosystems do not exclude beneficiaries and they can be depleted or degraded. For example, green space within communities provides sustainable health services that reduces mortality and regulates the spread of vector borne disease. Research shows that people who are more engaged with regular access to natural areas have lower rates of diabetes, heart disease and psychological disorders. These ecological health services are regularly depleted through urban development projects that do not factor in the common-pool value of ecosystems.

The ecological commons delivers a diverse supply of community services that sustains the well-being of human society. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, an international UN initiative involving more than 1,360 experts worldwide, identifies four main ecosystem service types having 30 sub-categories stemming from natural capital. The ecological commons includes provisioning (e.g., food, raw materials, medicine, water supplies), regulating (e.g., climate, water, soil retention, flood retention), cultural (e.g., science and education, artistic, spiritual), and supporting (e.g., soil formation, nutrient cycling, water cycling) services.

Sixth mass extinction

Global assessments of biodiversity indicate that the current epoch, the Holocene (or Anthropocene) is a sixth mass extinction. Species loss is accelerating at 100–1000 times faster than average background rates in the fossil record. The field of conservation biology involves ecologists that are researching, confronting, and searching for solutions to sustain the planet's ecosystems for future generations.

"Human activities are associated directly or indirectly with nearly every aspect of the current extinction spasm."

Nature is a resilient system. Ecosystems regenerate, withstand, and are forever adapting to fluctuating environments. Ecological resilience is an important conceptual framework in conservation management and it is defined as the preservation of biological relations in ecosystems that persevere and regenerate in response to disturbance over time. However, persistent, systematic, large and nonrandom disturbance caused by the niche constructing behavior of human beings, habitat conversion and land development, has pushed many of the Earth's ecosystems to the extent of their resilient thresholds. Three planetary thresholds have already been crossed, including biodiversity loss, climate change, and nitrogen cycles. These biophysical systems are ecologically interrelated and naturally resilient, but human civilization has transitioned the planet to an Anthropocene epoch, where the threshold for planetary scale resilience has been crossed and the ecological state of the Earth is deteriorating rapidly to the detriment of humanity. The world's fisheries and oceans, for example, are facing dire challenges as the threat of global collapse appears imminent, with serious ramifications for the well-being of humanity; while the Anthropocene is yet to be classified as an official epoch, current evidence suggest that "an epoch-scale boundary has been crossed within the last two centuries." The ecology of the planet is further threatened by global warming, but investments in nature conservation can provide a regulatory feedback to store and regulate carbon and other greenhouse gases.

Ecological footprint

In 1992, William Rees developed the ecological footprint concept. The ecological footprint and its close analog the water footprint has become a popular way of accounting for the level of impact that human society is imparting on the Earth's ecosystems. All indications are that the human enterprise is unsustainable as the footprint of society is placing too much stress on the ecology of the planet. The WWF 2008 living planet report and other researchers report that human civilization has exceeded the bio-regenerative capacity of the planet. This means that the footprint of human consumption is extracting more natural resources than can be replenished by ecosystems around the world.

Ecological economics

Ecological economics is an economic science that extends its methods of valuation onto nature in an effort to address the inequity between market growth and biodiversity loss. Natural capital is the stock of materials or information stored in biodiversity that generates services that can enhance the welfare of communities. Population losses are the more sensitive indicator of natural capital than are species extinction in the accounting of ecosystem services. The prospect for recovery in the economic crisis of nature is grim. Populations, such as local ponds and patches of forest are being cleared away and lost at rates that exceed species extinctions. The mainstream growth-based economic system adopted by governments worldwide does not include a price or markets for natural capital. This type of economic system places further ecological debt onto future generations.

Human societies are increasingly being placed under stress as the ecological commons is diminished through an accounting system that has incorrectly assumed "... that nature is a fixed, indestructible capital asset." The current wave of threats, including massive extinction rates and concurrent loss of natural capital to the detriment of human society, is happening rapidly. This is called a biodiversity crisis, because 50% of the worlds species are predicted to go extinct within the next 50 years. Conventional monetary analyses are unable to detect or deal with these sorts of ecological problems. Multiple global ecological economic initiatives are being promoted to solve this problem. For example, governments of the G8 met in 2007 and set forth The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) initiative:

In a global study we will initiate the process of analyzing the global economic benefit of biological diversity, the costs of the loss of biodiversity and the failure to take protective measures versus the costs of effective conservation.

The work of Kenneth E. Boulding is notable for building on the integration between ecology and its economic origins. Boulding drew parallels between ecology and economics, most generally in that they are both studies of individuals as members of a system, and indicated that the “household of man” and the “household of nature” could somehow be integrated to create a perspective of greater value.

Interdisciplinary approaches

Human ecology expands functionalism from ecology to the human mind. People's perception of a complex world is a function of their ability to be able to comprehend beyond the immediate, both in time and in space. This concept manifested in the popular slogan promoting sustainability: "think global, act local." Moreover, people's conception of community stems from not only their physical location but their mental and emotional connections and varies from "community as place, community as way of life, or community of collective action."

In these early years, human ecology was still deeply enmeshed in its respective disciplines: geography, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and economics. Scholars through the 1970s until present have called for a greater integration between all of the scattered disciplines that has each established formal ecological research.

In art

While some of the early writers considered how art fit into a human ecology, it was Sears who posed the idea that in the long run human ecology will in fact look more like art. Bill Carpenter (1986) calls human ecology the "possibility of an aesthetic science," renewing dialogue about how art fits into a human ecological perspective. According to Carpenter, human ecology as an aesthetic science counters the disciplinary fragmentation of knowledge by examining human consciousness.

In education

While the reputation of human ecology in institutions of higher learning is growing, there is no human ecology at the primary or secondary education levels, with one notable exception, Syosset High School, in Long Island, New York. Educational theorist Sir Kenneth Robinson has called for diversification of education to promote creativity in academic and non-academic (i.e.- educate their “whole being”) activities to implement a “new conception of human ecology”.

Bioregionalism and urban ecology

In the late 1960s, ecological concepts started to become integrated into the applied fields, namely architecture, landscape architecture, and planning. Ian McHarg called for a future when all planning would be “human ecological planning” by default, always bound up in humans’ relationships with their environments. He emphasized local, place-based planning that takes into consideration all the “layers” of information from geology to botany to zoology to cultural history. Proponents of the new urbanism movement, like James Howard Kunstler and Andres Duany, have embraced the term human ecology as way to describe the problem of—and prescribe the solutions for—the landscapes and lifestyles of an automobile oriented society. Duany has called the human ecology movement to be "the agenda for the years ahead." While McHargian planning is still widely respected, the landscape urbanism movement seeks a new understanding between human and environment relations. Among these theorists is Frederich Steiner, who published Human Ecology: Following Nature's Lead in 2002 which focuses on the relationships among landscape, culture, and planning. The work highlights the beauty of scientific inquiry by revealing those purely human dimensions which underlie our concepts of ecology. While Steiner discusses specific ecological settings, such as cityscapes and waterscapes, and the relationships between socio-cultural and environmental regions, he also takes a diverse approach to ecology—considering even the unique synthesis between ecology and political geography. Deiter Steiner's 2003 Human Ecology: Fragments of Anti-fragmentary view of the world is an important expose of recent trends in human ecology. Part literature review, the book is divided into four sections: "human ecology", "the implicit and the explicit", "structuration", and "the regional dimension". Much of the work stresses the need for transciplinarity, antidualism, and wholeness of perspective.