| Barley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Drawing of barley | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Hordeum |

| Species: | H. vulgare

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hordeum vulgare | |

| Synonyms | |

|

| |

List |

Barley (Hordeum vulgare), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Barley has been used as animal fodder, as a source of fermentable material for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods. It is used in soups and stews, and in barley bread of various cultures. Barley grains are commonly made into malt in a traditional and ancient method of preparation.

In 2017, barley was ranked fourth among grains in quantity produced (149 million tonnes) behind maize, rice and wheat.

Etymology

The Old English word for barley was bere, which traces back to Proto-Indo-European and is cognate to the Latin word farina "flour".

The direct ancestor of modern English barley in Old English was the derived adjective bærlic, meaning "of barley". The first citation of the form bærlic in the Oxford English Dictionary dates to around 966 CE, in the compound word bærlic-croft. The underived word bære survives in the north of Scotland as bere, and refers to a specific strain of six-row barley grown there.

The word barn, which originally meant "barley-house", is also rooted in these words.

The Latin word hordeum, used as barley's scientific genus name, is derived from an Indo-European root meaning "bristly" after the long prickly awns of the ear of grain.

Biology

Barley is a member of the grass family. It is a self-pollinating, diploid species with 14 chromosomes. The wild ancestor of domesticated barley, Hordeum vulgare subsp. spontaneum, is abundant in grasslands and woodlands throughout the Fertile Crescent area of Western Asia and northeast Africa, and is abundant in disturbed habitats, roadsides, and orchards. Outside this region, the wild barley is less common and is usually found in disturbed habitats. However, in a study of genome-wide diversity markers, Tibet was found to be an additional center of domestication of cultivated barley.

Domestication

Wild barley (H. spontaneum) is the ancestor of domestic barley (H. vulgare). Over the course of domestication, barley grain morphology changed substantially, moving from an elongated shape to a more rounded spherical one. Additionally, wild barley has distinctive genes, alleles, and regulators with potential for resistance to abiotic or biotic stresses to cultivated barley and adaptation to climatic changes. Wild barley has a brittle spike; upon maturity, the spikelets separate, facilitating seed dispersal. Domesticated barley has nonshattering spikes, making it much easier to harvest the mature ears. The nonshattering condition is caused by a mutation in one of two tightly linked genes known as Bt1 and Bt2; many cultivars possess both mutations. The nonshattering condition is recessive, so varieties of barley that exhibit this condition are homozygous for the mutant allele.

Domestication in barley is followed by the change of key phenotypic traits at the genetic level. Little is known about the genetic variation among domesticated and wild genes in the chromosomal regions.

Two-row and six-row barley

Spikelets are arranged in triplets which alternate along the rachis. In wild barley (and other Old World species of Hordeum), only the central spikelet is fertile, while the other two are reduced. This condition is retained in certain cultivars known as two-row barleys. A pair of mutations (one dominant, the other recessive) result in fertile lateral spikelets to produce six-row barleys. Recent genetic studies have revealed that a mutation in one gene, vrs1, is responsible for the transition from two-row to six-row barley.

Two-row barley has a lower protein content than six-row barley, thus a more fermentable sugar content. High-protein barley is best suited for animal feed. Malting barley is usually lower protein ("low grain nitrogen", usually produced without a late fertilizer application) which shows more uniform germination, needs shorter steeping, and has less protein in the extract that can make beer cloudy. Two-row barley is traditionally used in English ale-style beers, with two-row malted summer barley being preferred for traditional German beers.

Amylase-rich six-row barley is common in some American lager-style beers, especially when adjuncts such as corn and rice are used.

Hulless barley

Hulless or "naked" barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook. f.) is a form of domesticated barley with an easier-to-remove hull. Naked barley is an ancient food crop, but a new industry has developed around uses of selected hulless barley to increase the digestible energy of the grain, especially for swine and poultry. Hulless barley has been investigated for several potential new applications as whole grain, and for its value-added products. These include bran and flour for multiple food applications.

Classification

In traditional classifications of barley, these morphological differences have led to different forms of barley being classified as different species. Under these classifications, two-row barley with shattering spikes (wild barley) is classified as Hordeum spontaneum K. Koch. Two-row barley with nonshattering spikes is classified as H. distichum L., six-row barley with nonshattering spikes as H. vulgare L. (or H. hexastichum L.), and six-row with shattering spikes as H. agriocrithon Åberg.

Because these differences were driven by single-gene mutations, coupled with cytological and molecular evidence, most recent classifications treat these forms as a single species, H. vulgare L.

Cultivars

- Vocabulary

- DON: Acronym for deoxynivalenol, a toxic byproduct of Fusarium head blight, also known as vomitoxin

- Heading date: A parameter in barley cultivation

- Lodging: The bending over of the stems near ground level

- Nutans: A designation for a variety with a lax ear, as opposed to 'erectum' (with an erect ear)

- QCC: A pathotype of stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici)

- Rachilla: The part of a spikelet that bears the florets, the length of the rachilla hairs is a characteristic of barley varieties

- Cultivars

- 'Azure', a six-row, blue-aleurone malting barley released in 1982, it was high-yielding with strong straw, but was susceptible to loose smut.

- 'Beacon', a six-row malting barley with rough awns, short rachilla hairs and colorless aleurone, it was released in 1973, and was the first North Dakota State University (NDSU) barley that had resistance to loose smut.

- Bere, a six-row barley, is currently cultivated mainly on 5-15 hectares of land in Orkney, Scotland. Two additional parcels on the island of Islay, Scotland, were planted in 2006 for Bruichladdich Distillery.

- 'Betzes', an old German two-row barley, was introduced into North America from Kraków, Poland, by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The Montana and Idaho agricultural experiment stations released Betzes in 1957. It is a midshort, medium strength-strawed, midseason-maturing barley. It has a midsize-to-large kernels with yellow aleurones. Betzes is susceptible to loose and covered smuts, rusts, and scald.

- 'Bowman', a two-rowed, smooth-awned variety, was jointly released by NDSU and USDA in 1984 as a feed barley, spring variety developed in North Dakota. It has good test weight and straw strength. It is resistant to wheat stem rust, but is susceptible to loose smut and barley yellow dwarf virus.

- 'Celebration', a variety developed by the barley breeding program at Busch Agricultural Resources, was released in 2008. Through a collaborative agreement between the NDSU Foundation Seedstocks (NDFSS) project and Busch Agricultural Resources, all foundation seed of 'Celebration' barley will be produced and distributed by the NDFSS. 'Celebration' has excellent agronomic performance and malt quality. It is a Midwestern variety, well-adapted for Minnesota, North Dakota, Idaho, and Montana, with medium-early maturity, medium-early heading, medium-short height, mid-lax head type, rough awns, short rachilla hairs, and colorless aleurone, moderately resistant to Septoria and net blotch. It has improved reaction to Fusarium head blight and consistently lower DON content.

- 'Centennial', a Canadian variety, was developed from the cross of 'Lenta' x 'Sanalta' by the University of Alberta. It is a two-row, relatively short, stiff-strawed, late-maturing variety. The kernel is midlong with yellow aleurone. It was released as a feed barley.

- 'Compana', an American variety, was developed from a composite cross by the Idaho and Montana Agricultural Experiment Stations in cooperation with the USDA's Plant Science Research Division. It was released by Montana in 1941. 'Compana' is a two-row variety with moderately weak straw, midshort with midseason maturity. The kernels are long and wide with yellow aleurone. This variety is resistant to loose smut and moderately resistant to covered smut.Seven mid-20th-century malt barley varieties studied at Canterbury Agricultural College

- 'Conlon', a two-row barley, was released by NDSU in 1996. Test weight and yield are better than 'Bowman'. Yield is equal to 'Stark'. 'Conlon' heads earlier than 'Bowman' and shows good heat tolerance by kernel plumpness. It is resistant to powdery mildew and net blotch, but is moderately susceptible to spot blotch. It is prone to lodging under high-yield growing conditions. It appears best adapted to western North Dakota and adjacent western states.

- 'Diamant', a Czech high-yield, is a short-height, mutant variety created with X-rays.

- 'Dickson', a six-row, rough-awned variety, was released by NDSU in 1965. It had good straw strength and was resistant to stem rust, but susceptible to loose smut. 'Dickson' had more resistance to prevalent leaf spot diseases than 'Trophy', 'Larker', and 'Traill'. It was similar to 'Trophy' in heading date, plant height, and straw strength. It had less plumpness than 'Trophy' and 'Larker', but more than 'Traill' and 'Kindred'.

- 'Drummond', a six-row malting variety, was released by NDSU in 2000. It has white aleurone, long rachilla hairs and semismooth awns. 'Drummond' has better straw strength than current six-row varieties. Heading date is similar to Robust and plant height is similar to Stander. It is resistant to spot blotch and moderately susceptible to net blotch. However, its net blotch resistance is better than any current variety. Fusarium head blight reaction is similar to that of 'Robust'. It is resistant to prevalent races of wheat stem rust, but is susceptible to pathotype Pgt-QCC. 'Drummond' is on the American Malting Barley Association's list of recommended varieties. In two years of plant-scale evaluation, 'Drummond' was found satisfactory by Anheuser-Busch, Inc. and Miller Brewing.

- 'Excel', a six-row, white-aleurone malting barley, was released by Minnesota in 1990. Shorter in height than other six-row barleys grown at that time, it is high-yielding with medium-early maturity, moderately strong straw, smooth awns, and long rachilla hairs. It has high resistance to stem rust and moderate resistance to spot blotch, but is susceptible to loose smut. Malting traits are equal or greater than 'Morex' with plum kernel percentage lower than 'Robust'.

- 'Foster', a six-row, white-aleurone malting barley, was released by NDSU in 1995. About one day earlier and slightly shorter than 'Robust', it is higher-yielding than 'Morex', 'Robust', and 'Hazen'. Straw strength is similar to 'Excel' and 'Stander', but better than 'Robust'. It is moderately susceptible to net blotch, but resistant to spot blotch. Protein is 1.5% lower than 'Robust' and 'Morex'.

- 'Glenn', a six-row, white-aleurone variety, was released by NDSU in 1978. 'Glenn' was resistant to prevalent races of loose and covered smut with better resistance to leaf spot diseases than 'Larker'. It matured about two days earlier than 'Larker' and yielded about 10% more than 'Larker' and 'Beacon'.

- 'Golden Promise', an English semidwarf, is a salt-tolerant, mutant variety (created with gamma rays) used to make beer and whisky.

- 'Hazen', a six-row, smooth-awn, white-aleurone feed barley, was released by NDSU in 1984. 'Hazen' heads two days later than 'Glenn'. It is susceptible to loose smut.

- Highland barley is a crop cultivated on the Tibetan Plateau.

- 'Kindred' was released in 1941 and developed from a selection made by S.T. Lykken, a Kindred, North Dakota farmer. It was a six-row, rough-awned, medium-early Manchurian-type malting variety that gave good yields. 'Kindred' had stem rust resistance, but was moderately susceptible to spot blotch and Septoria. It was less susceptible to blight and root rot than 'Wisconsin 38'. It was medium-height with weak straw.

- 'Kindred L' is a reselection made to eliminate blue Manchurian types.

- 'Larker', a six-rowed, semi-smooth-awn malting barley, was first released in 1961. It was medium-maturity with moderate straw strength and medium height. 'Larker' was rust-resistant, but susceptible to leaf diseases and loose smut. It was superior to all other malt varieties for kernel plumpness at the time of release.

- 'Logan', released by NDSU in 1995, is classed as a nonmalting barley. It is a white-aleurone, two-row barley similar to 'Bowman' in heading date and plant height and similar to 'Morex' for foliar diseases. It has better yield, test weight, and lodging score, and lower protein, than 'Bowman' and 'Morex'.

- 'Lux' is a Danish variety.

- 'Manchurian', a blue-aleurone malting variety, was released by NDSU in 1922. It had weak to moderate-stiff straw and was susceptible to stem rust. It was developed from false stripe virus-free stock.

- 'Manscheuri', also designated 'Accession No. 871', is a six-row barley that may have been first released by NDSU before 1904. It outyielded most of the common types being grown in North Dakota at the time. It had stiffer straw than varieties at the time and a longer head filled with large, plump kernels.

- 'Mansury', also designated 'Accession No. 172', is a two-row barley first released by NDSU about 1905.

- 'Maris Otter' is an English two-row winter variety commonly used in the production of malt for traditional British beers or as a 'maltier' two-row substitute in any style. It remains popular for craft beer and among homebrewers.

- 'Morex', a six-row, white-aleurone, smooth-awn malting variety, was released by Minnesota in 1978. 'Morex', which stands for "more extract", is highly resistant to stem rust, moderate to spot blotch, and susceptible to loose smut.

- 'Nordal', a spring nutans variety from Carlsberg Sweden, was released in 1971.

- 'Nordic', a six-row, colorless-aleurone feed barley, was released in 1971. It had rough awns and short rachilla hairs. Yield was similar to 'Dickson', but greater than 'Larker'. Kernel plumpness and test weight was superior to 'Dickson', but less than 'Larker'. Lodging, spot, and net blotch resistance was similar to 'Dickson', but it had higher resistance to Septoria leaf blotch. It showed less leaf rust symptoms compared to other varieties at the time.

- 'Optic'

- 'Pallas'

- 'Park', a six-row, white-aleurone, malting barley, was released in 1978. 'Park' had better resistance to leaf spot diseases, spot blotch, net blotch, and Septoria leaf blotch than 'Larker'.

- 'Plumage Archer' is an English malt variety.

- 'Pearl'

- 'Pinnacle', a variety released by the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station in 2006, has high yield, low protein, long rachilla hairs, smooth awns, white aleurone, medium-late maturity, medium height, and strong straw strength.

- 'Proctor' is a parent cultivar of 'Maris Otter'.

- 'Pioneer' is a parent cultivar of 'Maris Otter'.

- 'Rawson', a variety developed by the NDSU Barley Breeding Program, was released by the North Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station in 2005. 'Rawson's' general characteristics were very large kernels, loose hull, long rachilla hairs, rough awns, white aleurone, medium maturity, medium height, and medium straw strength.

- 'Robust', a six-row, white-aleurone malting variety, was released by Minnesota in 1983. Maturity is two days later than 'Morex'.

- 'Sioux', a selection from Tregal released by NDSU, was a six-row, medium-early variety with white aleurone, rough awns, and long rachilla hairs. It was high-yielding with plump kernels. Its disease reaction was similar to 'Tregal'.

- 'Stark', a two-row nonmalting barley released by NDSU in 1991, has stiff straw and large kernels, and appears best adapted to western North Dakota and adjacent western states. 'Stark' is about one day later and two inches shorter than 'Bowman', with equal or better test weight. 'Stark' yields about 10% better than 'Bowman'. It is moderately resistant to net and spot blotch, but is susceptible to loose smut, leaf rust and the QCC race of wheat stem rust.

- 'Steptoe', a white-kerneled, rough-awned feed variety, was released by Washington State University in 1973. 'Steptoe' is widely adapted and has been one of the highest yielding and most popular six-rowed feed varieties in the inland Pacific northwest for many years.

- 'Tradition', a variety with excellent agronomic performance and malt quality, is well-adapted to Minnesota, North Dakota, Idaho, and Montana. 'Tradition' has medium relative maturity, medium-short height, and very strong straw. It has a nodding head type, semismooth awns, long rachilla hairs. and white aleurone.

- 'Traill', a medium-early, rough-awn, white-aleurone malting variety, was released by NDSU in 1956. It was resistant to stem rust and had the same reaction to spot blotch and Septoria as 'Kindred'. 'Traill' had greater yield and straw strength than 'Kindred', but had smaller kernel size.

- 'Tregal', a high-yield, smooth-awn, six-row feed barley, was released by NDSU in 1943. It was medium-early with short, stiff straw, erect head, and high resistance to loose smut. 'Tregal' was similar to 'Kindred' for reaction to spot blotch with similar tolerance to Septoria.

- 'Trophy', a six-row, rough-awn malting variety with colorless aleurone, was released by NDSU in 1964. Similar to 'Traill' and 'Kindred' in plant height, heading date, and test weight, it had a higher percentage of plump kernels. Its yield in North Dakota was greater than 'Kindred' and similar to 'Traill'. Similar to 'Kindred' and 'Traill', it was resistant to stem rust, but susceptible to loose smut and Septoria leaf blotch. It had some field resistance to net blotch. It had greater straw strength than 'Kindred'. 'Trophy' had greater enzymatic activity and quality than 'Traill'.

- 'Windich' is a Western Australian grain cultivar named after Tommy Windich (circa 1840–1876).

- 'Yagan' is a Western Australian grain cultivar named after Yagan (circa 1795-1833).

Chemistry

H. vulgare contains the phenolics caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid, the ferulic acid 8,5'-diferulic acid, the flavonoids catechin-7-O-glucoside, saponarin, catechin, procyanidin B3, procyanidin C2, and prodelphinidin B3, and the alkaloid hordenine.

History

Origin

Barley was one of the first domesticated grains in the Fertile Crescent, an area of relatively abundant water in Western Asia, and near the Nile river of northeast Africa. The grain appeared in the same time as einkorn and emmer wheat. Wild barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum) ranges from North Africa and Crete in the west, to Tibet in the east. According to some scholars, the earliest evidence of wild barley in an archaeological context comes from the Epipaleolithic at Ohalo II at the southern end of the Sea of Galilee. The remains were dated to about 8500 BCE. Other scholars have written that the earliest evidence comes from Mesopotamia, specifically the Jarmo region of modern day Iraq.

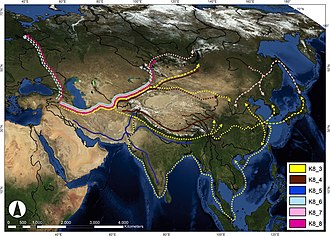

Spread of cultivated barley: genetic analysis

One of the world's most important crops, barley, was domesticated in the Near East around 11,000 years ago (circa 9,000 BCE). Barley is a highly resilient crop, able to be grown in varied and marginal environments, such as in regions of high altitude and latitude. Archaeobotanical evidence shows that barley had spread throughout Eurasia by 2,000 BCE. To further elucidate the routes by which barley cultivation was spread through Eurasia, genetic analysis was used to determine genetic diversity and population structure in extant barley taxa. Genetic analysis shows that cultivated barley spread through Eurasia via several different routes, which were most likely separated in both time and space.

Dispersal

Some scholars believe domesticated barley (hordeum vulgare) originally spread from Central Asia to India, Persia, Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt. Some of the earliest domesticated barley occurs at aceramic ("pre-pottery") Neolithic sites, in the Near East such as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B layers of Tell Abu Hureyra, in Syria. By 4200 BCE domesticated barley occurs as far as in Eastern Finland and had reached Greece and Italy around the 4th c. BCE. Barley has been grown in the Korean Peninsula since the Early Mumun Pottery Period (circa 1500–850 BCE) along with other crops such as millet, wheat, and legumes.

Barley (known as Yava in both Vedic and Classical Sanskrit) is mentioned many times in Rigveda and other Indian scriptures as one of the principal grains in ancient India. Traces of Barley cultivation have also been found in post-Neolithic Bronze Age Harappan civilization 5700–3300 years before present.

In the Pulitzer Prize-winning book Guns, Germs, and Steel, Jared Diamond proposed that the availability of barley, along with other domesticable crops and animals, in southwestern Eurasia significantly contributed to the broad historical patterns that human history has followed over approximately the last 13,000 years; i.e., why Eurasian civilizations, as a whole, have survived and conquered others. Jared Diamond's proposition was criticized, however, for underemphasizing individual and cultural choice and autonomy. The anthropologist Jason Antrosio wrote, that "Diamond's account makes all the factors of European domination a product of a distant and accidental history" and "has almost no role for human agency–the ability people have to make decisions and influence outcomes. Europeans become inadvertent, accidental conquerors. Natives succumb passively to their fate." He added, "Jared Diamond has done a huge disservice to the telling of human history. He has tremendously distorted the role of domestication and agriculture in that history. Unfortunately his story-telling abilities are so compelling that he has seduced a generation of college-educated readers."

Barley beer was probably one of the first alcoholic drinks developed by Neolithic humans. Barley later on was used as currency. The ancient Sumerian word for barley was akiti. In ancient Mesopotamia, a stalk of barley was the primary symbol of the goddess Shala. Alongside emmer wheat, barley was a staple cereal of ancient Egypt, where it was used to make bread and beer. The general name for barley is jt (hypothetically pronounced "eat"); šma (hypothetically pronounced "SHE-ma") refers to Upper Egyptian barley and is a symbol of Upper Egypt. According to Deuteronomy 8:8, barley is one of the "Seven Species" of crops that characterize the fertility of the Promised Land of Canaan, and it has a prominent role in the Israelite sacrifices described in the Pentateuch (see e.g. Numbers 5:15). A religious importance extended into the Middle Ages in Europe, and saw barley's use in justice, via alphitomancy and the corsned.

| jt barley determinative/ideogram |

| ||||

| jt (common) spelling |

| ||||

| šma determinative/ideogram |

|

Rations of barley for workers appear in Linear B tablets in Mycenaean contexts at Knossos and at Mycenaean Pylos. In mainland Greece, the ritual significance of barley possibly dates back to the earliest stages of the Eleusinian Mysteries. The preparatory kykeon or mixed drink of the initiates, prepared from barley and herbs, referred in the Homeric hymn to Demeter, whose name some scholars believe meant "Barley-mother". The practice was to dry the barley groats and roast them before preparing the porridge, according to Pliny the Elder's Natural History (xviii.72). This produces malt that soon ferments and becomes slightly alcoholic.

Pliny also noted barley was a special food of gladiators known as hordearii, "barley-eaters". However, by Roman times, he added that wheat had replaced barley as a staple.

Tibetan barley has been a staple food in Tibetan cuisine since the fifth century CE. This grain, along with a cool climate that permitted storage, produced a civilization that was able to raise great armies. It is made into a flour product called tsampa that is still a staple in Tibet. The flour is roasted and mixed with butter and butter tea to form a stiff dough that is eaten in small balls.

In medieval Europe, bread made from barley and rye was peasant food, while wheat products were consumed by the upper classes. Potatoes largely replaced barley in Eastern Europe in the 19th century.

Genetics

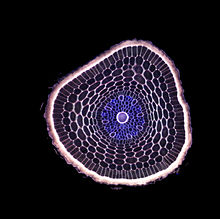

The genome of barley was sequenced in 2012, due to the efforts of the International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium and the UK Barley Sequencing Consortium.

The genome is composed of seven pairs of nuclear chromosomes (recommended designations: 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H and 7H), and one mitochondrial and one chloroplast chromosome, with a total of 5000 Mbp.

Abundant biological information is already freely available in several barley databases.

The wild barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum) found currently in the Fertile Crescent might not be the progenitor of the barley cultivated in Eritrea and Ethiopia, indicating that separate domestication may have occurred in eastern Africa.

Hybridization

Barley has been crossed with wheat with mixed results that have yet to prove commercially viable. The resulting hybrids have further been crossed with rye, but with even more limited results.

Production

| Barley production, 2018 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (millions of tonnes) |

In 2017, world production of barley was 149 million tonnes, led by Russia producing 14% of the world total. Australia, Germany, France, and Ukraine were major producers.

Cultivation

Barley is a widely adaptable crop. It is currently popular in temperate areas where it is grown as a summer crop and tropical areas where it is sown as a winter crop. Its germination time is one to three days. Barley grows under cool conditions, but is not particularly winter hardy.

Barley is more tolerant of soil salinity than wheat, which might explain the increase of barley cultivation in Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE onwards. Barley is not as cold tolerant as the winter wheats (Triticum aestivum), fall rye (Secale cereale) or winter triticale (× Triticosecale Wittm. ex A. Camus.), but may be sown as a winter crop in warmer areas of Australia and Great Britain.

Barley has a short growing season and is also relatively drought tolerant.

Plant diseases

Barley is known or likely to be susceptible to barley mild mosaic bymovirus, as well as bacterial blight. Barley yellow dwarf virus, vectored by the rice root aphid, can also cause serious crop injury. It can be susceptible to many diseases, but plant breeders have been working hard to incorporate resistance. The devastation caused by any one disease will depend upon the susceptibility of the variety being grown and the environmental conditions during disease development. Serious diseases of barley include powdery mildew caused by Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei, leaf scald caused by Rhynchosporium secalis, barley rust caused by Puccinia hordei, crown rust caused by Puccinia coronata, and various diseases caused by Cochliobolus sativus. Barley is also susceptible to head blight.

Food

| |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 515 kJ (123 kcal) |

28.2 g | |

| Sugars | 0.3 g |

| Dietary fiber | 3.8 g |

0.4 g | |

2.3 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 0 μg0% 5 μg56 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 7% 0.083 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 5% 0.062 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 14% 2.063 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 3% 0.135 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 9% 0.115 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 4% 16 μg |

| Vitamin B12 | 0% 0 μg |

| Choline | 3% 13.4 mg |

| Vitamin C | 0% 0 mg |

| Vitamin D | 0% 0 IU |

| Vitamin E | 0% 0.01 mg |

| Vitamin K | 1% 0.8 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 11 mg |

| Copper | 5% 0.105 mg |

| Iron | 10% 1.3 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 22 mg |

| Manganese | 12% 0.259 mg |

| Phosphorus | 8% 54 mg |

| Potassium | 2% 93 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 3 mg |

| Zinc | 9% 0.82 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 68.8 g |

| Cholesterol | 0 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Nutrition

In a 100 gram serving, cooked barley provides 123 kilocalories and is a good source (10% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of essential nutrients, including, dietary fiber, the B vitamin, niacin (14% DV), and dietary minerals including iron (10% DV) and manganese (12% DV) (table).

Preparation

Hulled barley (or covered barley) is eaten after removing the inedible, fibrous, outer hull. Once removed, it is called dehulled barley (or pot barley or scotch barley). Considered a whole grain, dehulled barley still has its bran and germ, making it a commonly consumed food. Pearl barley (or pearled barley) is dehulled barley which has been steam-processed further to remove the bran. It may be polished, a process known as "pearling". Dehulled or pearl barley may be processed into various barley products, including flour, flakes similar to oatmeal, and grits.

Barley meal, a wholemeal barley flour lighter than wheat meal but darker in colour, is used in gruel, in contrast to porridge which is made from oats. Barley meal gruel is known as sawiq in the Arab world. With a long history of cultivation in the Middle East, barley is used in a wide range of traditional Arabic, Assyrian, Israelite, Kurdish, and Persian foodstuffs including kashkak, kashk and murri. Barley soup is traditionally eaten during Ramadan in Saudi Arabia. Cholent or hamin (in Hebrew) is a traditional Jewish stew often eaten on Sabbath, in numerous recipes by both Mizrachi and Ashkenazi Jews. In Eastern and Central Europe, barley is also used in soups and stews such as ričet. In Africa, where it is a traditional food plant, it has the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development, and support sustainable landcare.

The six-row variety bere is cultivated in Orkney, Shetland, Caithness and the Western Isles in the Scottish Highlands and islands. When milled into beremeal, it is used locally in bread, biscuits, and the traditional beremeal bannock.

Health implications

According to Health Canada and the US Food and Drug Administration, consuming at least 3 grams per day of barley beta-glucan or 0.75 grams per serving of soluble fiber can lower levels of blood cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.

Eating whole-grain barley, as well as other high-fiber grains, improves regulation of blood sugar (i.e., reduces blood glucose response to a meal). Consuming breakfast cereals containing barley over weeks to months also improved cholesterol levels and glucose regulation.

Like wheat, rye, and their hybrids and derivatives, barley contains gluten, which makes it an unsuitable grain for consumption by people with gluten-related disorders, such as celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy sufferers, among others. Nevertheless, some wheat allergy patients can tolerate barley or rye.

Beverages

Alcoholic beverages

Barley is a key ingredient in beer and whisky production. Two-row barley is traditionally used in German and English beers. Six-row barley was traditionally used in US beers, but both varieties are in common usage now. Distilled from green beer, whisky has been made primarily from barley in Ireland and Scotland, while other countries have used more diverse sources of alcohol, such as the more common corn, rye and wheat in the USA. In the US, a grain type may be identified on a whisky label if that type of grain constitutes 51% or more of the ingredients and certain other conditions are satisfied. About 25% of the United States' production of barley is used for malting, for which barley is the best-suited grain.

Barley wine is a style of strong beer from the English brewing tradition. Another alcoholic drink known by the same name, enjoyed in the 18th century, was prepared by boiling barley in water, then mixing the barley water with white wine and other ingredients, such as borage, lemon and sugar. In the 19th century, a different barley wine was made prepared from recipes of ancient Greek origin.

Nonalcoholic beverages

Nonalcoholic drinks such as barley water and roasted barley tea have been made by boiling barley in water. In Italy, barley is also sometimes used as coffee substitute, caffè d'orzo (coffee of barley).

Other uses

Animal feed

Half of the United States' barley production is used as livestock feed. Barley is an important feed grain in many areas of the world not typically suited for maize production, especially in northern climates—for example, northern and eastern Europe. Barley is the principal feed grain in Canada, Europe, and in the northern United States. A finishing diet of barley is one of the defining characteristics of western Canadian beef used in marketing campaigns.

As of 2014, an enzymatic process can be used to make a high-protein fish feed from barley, which is suitable for carnivorous fish such as trout and salmon.

Algistatic

Barley straw, in England, is placed in mesh bags and floated in fish ponds or water gardens to help prevent algal growth without harming pond plants and animals. Barley straw has not been approved by the EPA for use as a pesticide and its effectiveness as an algae regulator in ponds has produced mixed results, with either more efficacy against phytoplankton algae versus mat-forming algae, or no significant change, during university testing in the US and the UK.

Measurement

Barley grains were used for measurement in England, there being three or four barleycorns to the inch and four or five poppy seeds to the barleycorn. The statute definition of an inch was three barleycorns, although by the 19th century, this had been superseded by standard inch measures. This unit still persists in the shoe sizes used in Britain and the USA.

As modern studies show, the actual length of a kernel of barley varies from as short as 4–7 mm (5⁄32–9⁄32 in) to as long as 12–15 mm (15⁄32–19⁄32 in) depending on the cultivar. Older sources claimed the average length of a grain of barley being 8.8 mm (0.345 in).

The barleycorn was known as arpa in Turkish, and the feudal system in Ottoman Empire employed the term arpalik, or "barley-money", to refer to a second allowance made to officials to offset the costs of fodder for their horses.

Ornamental

A new stabilized variegated variety of H. vulgare, billed as H. vulgare variegate, has been introduced for cultivation as an ornamental and pot plant for pet cats to nibble.

Cultural

In English folklore, the figure of John Barleycorn in the folksong of the same name is a personification of barley, and of the alcoholic beverages made from it: beer and whisky. In the song, John Barleycorn is represented as suffering attacks, death, and indignities that correspond to the various stages of barley cultivation, such as reaping and malting.