| |

| Author | John Maynard Keynes |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Nonfiction |

| Publisher | Palgrave Macmillan |

Publication date | 1936 |

| Media type | Print paperback |

| Pages | 472 (2007 edition) |

| ISBN | 978-0-230-00476-4 |

| OCLC | 62532514 |

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money of 1936 is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and contributing much of its terminology – the "Keynesian Revolution". It had equally powerful consequences in economic policy, being interpreted as providing theoretical support for government spending in general, and for budgetary deficits, monetary intervention and counter-cyclical policies in particular. It is pervaded with an air of mistrust for the rationality of free-market decision making.

Keynes denied that an economy would automatically adapt to provide full employment even in equilibrium, and believed that the volatile and ungovernable psychology of markets would lead to periodic booms and crises. The General Theory is a sustained attack on the classical economics orthodoxy of its time. It introduced the concepts of the consumption function, the principle of effective demand and liquidity preference, and gave new prominence to the multiplier and the marginal efficiency of capital.

Keynes's aims in the General Theory

The central argument of The General Theory is that the level of employment is determined not by the price of labour, as in classical economics, but by the level of aggregate demand. If the total demand for goods at full employment is less than the total output, then the economy has to contract until equality is achieved. Keynes thus denied that full employment was the natural result of competitive markets in equilibrium.

In this he challenged the conventional ('classical') economic wisdom of his day. In a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw on New Year's Day, 1935, he wrote:

I believe myself to be writing a book on economic theory which will largely revolutionize — not I suppose, at once but in the course of the next ten years — the way the world thinks about its economic problems. I can't expect you, or anyone else, to believe this at the present stage. But for myself I don't merely hope what I say,— in my own mind, I'm quite sure.

The first chapter of the General theory (only half a page long) has a similarly radical tone:

I have called this book the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, placing the emphasis on the prefix general. The object of such a title is to contrast the character of my arguments and conclusions with those of the classical theory of the subject, upon which I was brought up and which dominates the economic thought, both practical and theoretical, of the governing and academic classes of this generation, as it has for a hundred years past. I shall argue that the postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to the general case, the situation which it assumes being a limiting point of the possible positions of equilibrium. Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience.

Summary of the General Theory

Keynes's main theory (including its dynamic elements) is presented in Chapters 2-15, 18, and 22, which are summarised here. A shorter account will be found in the article on Keynesian economics. The remaining chapters of Keynes's book contain amplifications of various sorts and are described later in this article.

Book I: Introduction

The first book of the The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is a repudiation of Say's Law. The classical view for which Keynes made Say a mouthpiece held that the value of wages was equal to the value of the goods produced, and that the wages were inevitably put back into the economy sustaining demand at the level of current production. Hence, starting from full employment, there cannot be a glut of industrial output leading to a loss of jobs. As Keynes put it on p. 18, "supply creates its own demand".

Stickiness of wages in money terms

Say's Law depends on the operation of a market economy. If there is unemployment (and if there are no distortions preventing the employment market from adjusting to it) then there will be workers willing to offer their labour at less than the current wage levels, leading to downward pressure on wages and increased offers of jobs.

The classics held that full employment was the equilibrium condition of an undistorted labour market, but they and Keynes agreed in the existence of distortions impeding transition to equilibrium. The classical position had generally been to view the distortions as the culprit and to argue that their removal was the main tool for eliminating unemployment. Keynes on the other hand viewed the market distortions as part of the economic fabric and advocated different policy measures which (as a separate consideration) had social consequences which he personally found congenial and which he expected his readers to see in the same light.

The distortions which have prevented wage levels from adapting downwards have lain in employment contracts being expressed in monetary terms; in various forms of legislation such as the minimum wage and in state-supplied benefits; in the unwillingness of workers to accept reductions in their income; and in their ability through unionisation to resist the market forces exerting downward pressure on them.

Keynes accepted the classical relation between wages and the marginal productivity of labour, referring to it on page 5 as the "first postulate of classical economics" and summarising it as saying that "The wage is equal to the marginal product of labour".

The first postulate can be expressed in the equation y'(N) = W/p, where y(N) is the real output when employment is N, and W and p are the wage rate and price rate in money terms (and hence W/p is the wage rate in real terms). A system can be analysed on the assumption that W is fixed (i.e. that wages are fixed in money terms) or that W/p is fixed (i.e. that they are fixed in real terms) or that N is fixed (e.g. if wages adapt to ensure full employment). All three assumptions had at times been made by classical economists, but under the assumption of wages fixed in money terms the 'first postulate' becomes an equation in two variables (N and p), and the consequences of this had not been taken into account by the classical school.

Keynes proposed a 'second postulate of classical economics' asserting that the wage is equal to the marginal disutility of labour. This is an instance of wages being fixed in real terms. He attributes the second postulate to the classics subject to the qualification that unemployment may result from wages being fixed by legislation, collective bargaining, or 'mere human obstinacy' (p6), all of which are likely to fix wages in money terms.

Outline of Keynes's theory

Keynes's economic theory is based on the interaction between demands for saving, investment, and liquidity (i.e. money). Saving and investment are necessarily equal, but different factors influence decisions concerning them. The desire to save, in Keynes's analysis, is mostly a function of income: the wealthier people are, the more wealth they will seek to put aside. The profitability of investment, on the other hand, is determined by the relation between the return available to capital and the interest rate. The economy needs to find its way to an equilibrium in which no more money is being saved than will be invested, and this can be accomplished by contraction of income and a consequent reduction in the level of employment.

In the classical scheme it is the interest rate rather than income which adjusts to maintain equilibrium between saving and investment; but Keynes asserts that the rate of interest already performs another function in the economy, that of equating demand and supply of money, and that it cannot adjust to maintain two separate equilibria. In his view it is the monetary role which wins out. This is why Keynes's theory is a theory of money as much as of employment: the monetary economy of interest and liquidity interacts with the real economy of production, investment and consumption.

Book II: Definitions and ideas

The choice of units

Keynes sought to allow for the lack of downwards flexibility of wages by constructing an economic model in which the money supply and wage rates were externally determined (the latter in money terms), and in which the main variables were fixed by the equilibrium conditions of various markets in the presence of these facts.

Many of the quantities of interest, such as income and consumption, are monetary. Keynes often expresses such quantities in wage units (Chapter 4): to be precise, a value in wage units is equal to its price in money terms divided by W, the wage (in money units) per man-hour of labour. Keynes generally writes a subscript w on quantities expressed in wage units, but in this account we omit the w. When, occasionally, we use real terms for a value which Keynes expresses in wage units we write it in lower case (e.g. y rather than Y).

As a result of Keynes's choice of units, the assumption of sticky wages, though important to the argument, is largely invisible in the reasoning. If we want to know how a change in the wage rate would influence the economy, Keynes tells us on p. 266 that the effect is the same as that of an opposite change in the money supply.

The identity of saving and investment

The relationship between saving and investment, and the factors influencing their demands, play an important role in Keynes's model. Saving and investment are considered to be necessarily equal for reasons set out in Chapter 6 which looks at economic aggregates from the viewpoint of manufacturers. The discussion is intricate, considering matters such as the depreciation of machinery, but is summarised on p. 63:

Provided it is agreed that income is equal to the value of current output, that current investment is equal to the value of that part of current output which is not consumed, and that saving is equal to the excess of income over consumption... the equality of saving and investment necessarily follows.

This statement incorporates Keynes's definition of saving, which is the normal one.

Book III: The propensity to consume

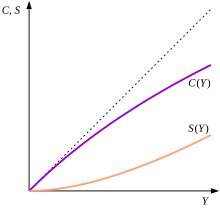

Book III of the General Theory is given over to the propensity to consume, which is introduced in Chapter 8 as the desired level of expenditure on consumption (for an individual or aggregated over an economy). The demand for consumer goods depends chiefly on the income Y and may be written functionally as C(Y). Saving is that part of income which is not consumed, so the propensity to save S(Y) is equal to Y–C(Y). Keynes discusses the possible influence of the interest rate r on the relative attractiveness of saving and consumption, but regards it as 'complex and uncertain' and leaves it out as a parameter.

His seemingly innocent definitions embody an assumption whose consequences will be considered later. Since Y is measured in wage units, the proportion of income saved is considered to be unaffected by the change in real income resulting from a change in the price level while wages stay fixed. Keynes acknowledges that this is undesirable in Point (1) of Section II.

In Chapter 9 he provides a homiletic enumeration of the motives to consume or not to do so, finding them to lie in social and psychological considerations which can be expected to be relatively stable, but which may be influenced by objective factors such as 'changes in expectations of the relation between the present and the future level of income' (p95).

The marginal propensity to consume and the multiplier

The marginal propensity to consume, C'(Y), is the gradient of the purple curve, and the marginal propensity to save S'(Y) is equal to 1–C'(Y). Keynes states as a 'fundamental psychological law' (p96) that the marginal propensity to consume will be positive and less than unity.

Chapter 10 introduces the famous 'multiplier' through an example: if the marginal propensity to consume is 90%, then 'the multiplier k is 10; and the total employment caused by (e.g.) increased public works will be ten times the employment caused by the public works themselves' (pp116f). Formally Keynes writes the multiplier as k=1/S'(Y). It follows from his 'fundamental psychological law' that k will be greater than 1.

Keynes's account is not clear until his economic system has been fully set out (see below). In Chapter 10 he describes his multiplier as being related to the one introduced by R. F. Kahn in 1931. The mechanism of Kahn's multiplier lies in an infinite series of transactions, each conceived of as creating employment: if you spend a certain amount of money, then the recipient will spend a proportion of what he or she receives, the second recipient will spend a further proportion again, and so forth. Keynes's account of his own mechanism (in the second para of p. 117) makes no reference to infinite series. By the end of the chapter on the multiplier, he uses his much quoted "digging holes" metaphor, against laissez-faire. In his provocation Keynes argues that "If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the banknotes up again" (...), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing".

Book IV: The inducement to invest

The rate of investment

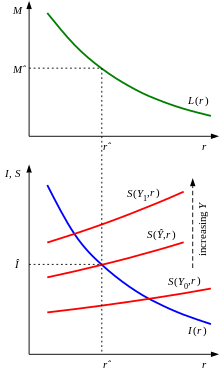

Book IV discusses the inducement to invest, with the key ideas being presented in Chapter 11. The 'marginal efficiency of capital' is defined as the annual revenue which will be yielded by an extra increment of capital as a proportion of its cost. The 'schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital' is the function which, for any rate of interest r, gives us the level of investment which will take place if all opportunities are accepted whose return is at least r. By construction this depends on r alone and is a decreasing function of its argument; it is illustrated in the diagram, and we shall write it as I (r).

This schedule is a characteristic of the current industrial process which Irving Fisher described as representing the 'investment opportunity side of interest theory'; and in fact the condition that it should equal S(Y,r) is the equation which determines the interest rate from income in classical theory. Keynes is seeking to reverse the direction of causality (and omitting r as an argument to S()).

He interprets the schedule as expressing the demand for investment at any given value of r, giving it an alternative name: "We shall call this the investment demand-schedule..." (p136). He also refers to it as the 'demand curve for capital' (p178). For fixed industrial conditions, we conclude that 'the amount of investment... depends on the rate of interest' as John Hicks put it in 'Mr. Keynes and the "Classics"'.

Interest and liquidity preference

Keynes proposes two theories of liquidity preference (i.e. the demand for money): the first as a theory of interest in Chapter 13 and the second as a correction in Chapter 15. His arguments offer ample scope for criticism, but his final conclusion is that liquidity preference is a function mainly of income and the interest rate. The influence of income (which really represents a composite of income and wealth) is common ground with the classical tradition and is embodied in the Quantity Theory; the influence of interest had also been noted earlier, in particular by Frederick Lavington (see Hicks's Mr Keynes and the "Classics"). Thus Keynes's final conclusion may be acceptable to readers who question the arguments along the way. However he shows a persistent tendency to think in terms of the Chapter 13 theory while nominally accepting the Chapter 15 correction.

Chapter 13 presents the first theory in rather metaphysical terms. Keynes argues that:

It should be obvious that the rate of interest cannot be a return to saving or waiting as such. For if a man hoards his savings in cash, he earns no interest, though he saves just as much as before. On the contrary, the mere definition of the rate of interest tells us in so many words that the rate of interest is the reward for parting with liquidity for a specified period.

To which Jacob Viner retorted that:

By analogous reasoning he could deny that wages are the reward for labor, or that profit is the reward for risk-taking, because labor is sometimes done without anticipation or realization of a return, and men who assume financial risks have been known to incur losses as a result instead of profits.

Keynes goes on to claim that the demand for money is a function of the interest rate alone on the grounds that:

The rate of interest is... the "price" which equilibrates the desire to hold wealth in the form of cash with the available quantity of cash.

Frank Knight commented that this seems to assume that demand is simply an inverse function of price. The upshot from these reasonings is that:

Liquidity-preference is a potentiality or functional tendency, which fixes the quantity of money which the public will hold when the rate of interest is given; so that if r is the rate of interest, M the quantity of money and L the function of liquidity-preference, we have M = L(r). This is where, and how, the quantity of money enters into the economic scheme.

And specifically it determines the rate of interest, which therefore cannot be determined by the traditional factors of 'productivity and thrift'.

Chapter 15 looks in more detail at the three motives Keynes ascribes for the holding of money: the 'transactions motive', the 'precautionary motive', and the 'speculative motive'. He considers that demand arising from the first two motives 'mainly depends on the level of income' (p199), while the interest rate is 'likely to be a minor factor' (p196).

Keynes treats the speculative demand for money as a function of r alone without justifying its independence of income. He says that...

what matters is not the absolute level of r but the degree of its divergence from what is considered a fairly safe level...

but gives reasons to suppose that demand will nonetheless tend to decrease as r increases. He thus writes liquidity preference in the form L1(Y)+L2(r) where L1 is the sum of transaction and precautionary demands and L2 measures speculative demand. The structure of Keynes's expression plays no part in his subsequent theory, so it does no harm to follow Hicks by writing liquidity preference simply as L(Y,r).

'The quantity of money as determined by the action of the central bank' is taken as given (i.e. exogenous - p. 247) and constant (because hoarding is ruled out on page 174 by the fact that the necessary expansion of the money supply cannot be 'determined by the public').

Keynes does not put a subscript 'w' on L or M, implying that we should think of them in money terms. This suggestion is reinforced by his wording on page 172 where he says "Unless we measure liquidity-preference in terms of wage-units (which is convenient in some contexts)... ". But seventy pages later there is a fairly clear statement that liquidity preference and the quantity of money are indeed "measured in terms of wage-units" (p246).

The Keynesian economic system

Keynes's economic model

In Chapter 14 Keynes contrasts the classical theory of interest with his own, and in making the comparison he shows how his system can be applied to explain all the principal economic unknowns from the facts he takes as given. The two topics can be treated together because they are different ways of analysing the same equation.

Keynes's presentation is informal. To make it more precise we will identify a set of 4 variables – saving, investment, the rate of interest, and the national income – and a parallel set of 4 equations which jointly determine them. The graph illustrates the reasoning. The red S lines are shown as increasing functions of r in obedience to classical theory; for Keynes they should be horizontal.

The first equation asserts that the reigning rate of interest r̂ is determined from the amount of money in circulation M̂ through the liquidity preference function and the assumption that L(r̂)=M̂.

The second equation fixes the level of investment Î given the rate of interest through the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital as I(r̂).

The third equation tells us that saving is equal to investment: S(Y)=Î. The final equation tells us that the income Ŷ is the value of Y corresponding to the implied level of saving.

All this makes a satisfying theoretical system.

Three comments can be made concerning the argument. Firstly, no use is made of the 'first postulate of classical economics', which can be called on later to set the price level. Secondly, Hicks (in 'Mr Keynes and the "Classics"') presents his version of Keynes's system with a single variable representing both saving and investment; so his exposition has three equations in three unknowns.

And finally, since Keynes's discussion takes place in Chapter 14, it precedes the modification which makes liquidity preference depend on income as well as on the rate of interest. Once this modification has been made the unknowns can no longer be recovered sequentially.

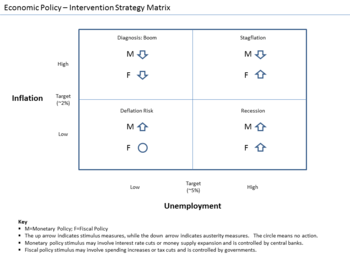

Keynesian economic intervention

The state of the economy, according to Keynes, is determined by four parameters: the money supply, the demand functions for consumption (or equivalently for saving) and for liquidity, and the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital determined by 'the existing quantity of equipment' and 'the state of long-term expectation' (p246).Adjusting the money supply is the domain of monetary policy. The effect of a change in the quantity of money is considered at p. 298. The change is effected in the first place in money units. According to Keynes's account on p. 295, wages will not change if there is any unemployment, with the result that the money supply will change to the same extent in wage units.

We can then analyse its effect from the diagram, in which we see that an increase in M̂ shifts r̂ to the left, pushing Î upwards and leading to an increase in total income (and employment) whose size depends on the gradients of all 3 demand functions. If we look at the change in income as a function of the upwards shift of the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital (blue curve), we see that as the level of investment is increased by one unit, the income must adjust so that the level of saving (red curve) is one unit greater, and hence the increase in income must be 1/S'(Y) units, i.e. k units. This is the explanation of Keynes's multiplier.

It does not necessarily follow that individual decisions to invest will have a similar effect, since decisions to invest above the level suggested by the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital are not the same thing as an increase in the schedule.

The equations of Keynesian and classical economics

Keynes's initial statement of his economic model (in Chapter 14) is based on his Chapter 13 theory of liquidity preference. His restatement in Chapter 18 doesn't take full account of his Chapter 15 revision, treating it as a source of 'repercussions' rather than as an integral component. It was left to John Hicks to give a satisfactory presentation. Equilibrium between supply and demand of money depends on two variables – interest rate and income – and these are the same two variables as are related by the equation between the propensity to save and the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital. It follows that neither equation can be solved in isolation and that they need to be considered simultaneously.

The 'first postulate' of classical economics was also accepted as valid by Keynes, though not used in the first four books of the General Theory. The Keynesian system can thus be represented by three equations in three variables as shown below, roughly following Hicks. Three analogous equations can be given for classical economics. As presented below they are in forms given by Keynes himself (the practice of writing r as an argument to V derives from his Treatise on money).

| Classical | Keynesian | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| y'(N) = W/p | The 'first postulate' | d(W·Y/p)/dN = W/p | |

| i (r) = s(y(N),r) | Determination of the interest rate | I (r) = S(Y) | Determination of income |

| M̂ = p·y(N) /V(r) | Quantity theory of money | M̂ = L(Y,r) | Liquidity preference |

| y, i, s in real terms; M̂ in money terms | Y, I, S, M̂, L in wage units | ||

Here y is written as a function of N, the number of workers employed; p is the price (in money terms) of a unit of real output; V(r) is the velocity of money; and W is the wage rate in money terms. N, p and r are the 3 variables we need to recover. In the Keynesian system income is measured in wage units and is therefore not a function of the level of employment alone since it will also vary with prices. The first postulate assumes that prices can be represented by a single variable. Strictly it should be modified to take account of the distinction between marginal wage cost and marginal prime cost.

The classics took the second equation as determining the rate of interest, the third as determining the price level, and the first as determining employment. Keynes believed that the last two equations could be solved together for Y and r, which is not possible in the classical system. He accordingly concentrated on these two equations, treating income as 'almost the same thing' as employment on p. 247. Here we see the benefit he has gained by simplifying the form of the consumption function. If he had written it (slightly more accurately) as C(Y,p/W), then he would have needed to bring in the first equation to get a solution.

If we wish to examine the classical system our task is made easier if we assume that the effect of the interest rate on the velocity of circulation is small enough to be ignored. This allows us to treat V as constant and solve the first and third equations (the 'first postulate' and the quantity theory) together, leaving the second equation to determine the interest rate from the result. We then find that the level of employment is given by the formula

.

The graph shows the numerator and denominator of the left-hand side as blue and green curves; their ratio – the pink curve – will be a decreasing function of N even if we don't assume diminishing marginal returns. The level of employment N̂ is given by the horizontal position at which the pink curve has a value of , and this is evidently a decreasing function of W.

Chapter 3: The principle of effective demand

The theoretical system we have described is developed over chapters 4–18, and is anticipated by a chapter which interprets Keynesian unemployment in terms of 'aggregate demand'.

The aggregate supply Z is the total value of output when N workers are employed, written functionally as φ(N). The aggregate demand D is manufacturers' expected proceeds, written as f(N). In equilibrium Z=D. D can be decomposed as D1+D2 where D1 is the propensity to consume, which may be written C(Y) or χ(N). D2 is explained as 'the volume of investment', and the equilibrium condition determining the level of employment is that D1+D2 should equal Z as functions of N. D2 can be identified with I (r).

The meaning of this is that in equilibrium the total demand for goods must equal total income. Total demand for goods is the sum of demand for consumption goods and demand for investment goods. Hence Y = C(Y) + S(Y) = C(Y) + I (r); and this equation determines a unique value of Y given r.

Samuelson's Keynesian cross is a graphical representation of the Chapter 3 argument.

Dynamic aspects of Keynes's theory

Chapter 5: Expectation as determining output and employment

Chapter 5 makes some common-sense observations on the role of expectation in economics. Short-term expectations govern the level of production chosen by an entrepreneur while long-term expectations govern decisions to adjust the level of capitalisation. Keynes describes the process by which the level of employment adapts to a change in long-term expectations and remarks that:

The level of employment at any time depends... not merely on the existing state of expectation but on the states of expectation which have existed over a certain past period. Nevertheless past expectations, which have not yet worked themselves out, are embodied in to-day's capital equipment... and only influence [the entrepreneur's] decisions in so far as they are so embodied.

Chapter 11: Expectation as influencing the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital

The main role of expectation in Keynes's theory lies in the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital which, as we have seen, is defined in Chapter 11 in terms of expected returns. Keynes differs here from Fisher whom he largely follows, but who defined the 'rate of return over cost' in terms of an actual revenue stream rather than its expectation. The step Keynes took here has a particular significance in his theory.

Chapters 14, 18: The schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital as influencing employment

Keynes differed from his classical predecessors in assigning a role to the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital in determining the level of employment. Its effect is mentioned in his presentations of his theory in Chapters 14 and 18 (see above).

Chapter 12: Animal spirits

Chapter 12 discusses the psychology of speculation and enterprise.

Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits – of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantified benefits... Thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die.

Keynes's picture of the psychology of speculators is less indulgent.

In point of fact, all sorts of considerations enter into the market valuation which are in no way relevant to the prospective yield... The recurrence of a bank-holiday may raise the market valuation of the British railway system by several million pounds.

(Henry Hazlitt examined some railway share prices and found that they did not bear out Keynes's assertion.)

Keynes considers speculators to be concerned...

...not with what an investment is really worth to a man who buys it 'for keeps', but with what the market will value it at, under the influence of mass psychology, three months or a year hence...

This battle of wits to anticipate the basis of conventional valuation a few months hence, rather than the prospective yield of an investment over a long term of years, does not even require gulls amongst the public to feed the maws of the professional;– it can be played by professionals amongst themselves. Nor is it necessary that anyone should keep his simple faith in the conventional basis of valuation having any genuine long-term validity. For it is, so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs – a pastime in which he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late, who passed the Old Maid to his neighbour before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops. These games can be played with zest and enjoyment, though all the players know that it is the Old Maid which is circulating, or that when the music stops some of the players will find themselves unseated.

Or, to change the metaphor slightly, professional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one's judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

Chapter 21: Wage behaviour

Keynes's theory of the trade cycle is a theory of the slow oscillation of money income which requires it to be possible for income to move upwards or downwards. If he had assumed that wages were constant, then upward motion of income would have been impossible at full employment, and he would have needed some mechanism to frustrate upward pressure if it arose in such circumstances.

His task is made easier by a less restrictive (but nonetheless crude) assumption concerning wage behaviour:

let us simplify our assumptions still further, and assume... that the factors of production... are content with the same money-wage so long as there is a surplus of them unemployed... ; whilst as soon as full employment is reached, it will thenceforward be the wage-unit and prices which will increase in exact proportion to the increase in effective demand.

Chapter 22: The trade cycle

Keynes's theory of the trade cycle is based on 'a cyclical change in the marginal efficiency of capital' induced by 'the uncontrollable and disobedient psychology of the business world' (pp313, 317).

The marginal efficiency of capital depends... on current expectations... But, as we have seen, the basis for such expectations is very precarious. Being based on shifting and unreliable evidence, they are subject to sudden and violent changes.

Optimism leads to a rise in the marginal efficiency of capital and increased investment, reflected – through the multiplier – in an even greater increase in income until 'disillusion falls upon an over-optimistic and over-bought market' which consequently falls with 'sudden and even catastrophic force' (p316).

There are reasons, given firstly by the length of life of durable assets... and secondly by the carrying-costs of surplus stocks, why the duration of the downward movement should have an order of magnitude... between, let us say, three and five years.

And a half cycle of 5 years tallies with Jevons's sunspot cycle length of 11 years.

Income fluctuates cyclically in Keynes's theory, with the effect being borne by prices if income increases during a period of full employment, and by employment in other circumstances.

Wage behaviour and the Phillips curve

Keynes's assumption about wage behaviour has been the subject of much criticism. It is likely that wage rates adapt partially to depression conditions, with the consequence that effects on employment are weaker than his model implies, but not that they disappear.

Lerner pointed out in the 40s that it was optimistic to hope that the workforce would be content with fixed wages in the presence of rising prices, and proposed a modification to Keynes's model. After this a succession of more elaborate models were constructed, many associated with the Phillips curve.

Keynes's optimistic prediction that an increase in money supply would be taken up by an increase in employment led to Jacob Viner's pessimistic prediction that "in a world organized in accordance with Keynes' specifications there would be a constant race between the printing press and the business agents of the trade unions".

Models of wage pressure on the economy needed frequent correction and the standing of Keynesian theory suffered. Geoff Tily wrote ruefully:

Finally, the most destructive step of all was Samuelson's and [Robert] Solow's incorporation of the Phillips curve into 'Keynesian' theory in a manner which traduced not only Phillips but also Keynes's careful work in the General Theory, Chapter 21, substituting for its subtlety an immutable relationship between inflation and employment. The 1970s combination of inflation and stagnating economic activity was at odds with this relationship, and therefore 'Keynesianism', and by association Keynes were rejected. Monetarism was merely waiting in the wings for this to happen.

Keynes's assumption of wage behaviour was not an integral part of his theory – very little in his book depends on it – and was avowedly a simplification: in fact it was the simplest assumption he could make without imposing an unnatural cap on money income.

The writing of the General Theory

Keynes drew a lot of help from his students in his progress from the Treatise on Money (1930) to the General Theory (1936). The Cambridge Circus, a discussion group founded immediately after the publication of the earlier work, reported to Keynes through Richard Kahn, and drew his attention to a supposed fallacy in the Treatise where Keynes had written:

Thus profits, as a source of capital increment for entrepreneurs, are a widow's cruse which remains undepleted however much of them may be devoted to riotous living.

The Circus disbanded in May 1931, but three of its member - Kahn, Austin and Joan Robinson – continued to meet in the Robinsons' house in Trumpington St. (Cambridge), forwarding comments to Keynes. This led to a 'Manifesto' of 1932 whose ideas were taken up by Keynes in his lectures. Kahn and Joan Robinson were well versed in marginalist theory which Keynes did not fully understand at the time (or possibly ever), pushing him towards adopting elements of it in the General Theory. During 1934 and 1935 Keynes submitted drafts to Kahn, Robinson and Roy Harrod for comment.

There has been uncertainty ever since over the extent of the collaboration, Schumpeter describing Kahn's "share in the historic achievement" as not having "fallen very far short of co-authorship" while Kahn denied the attribution.

Keynes's method of writing was unusual:

Keynes drafted rapidly in pencil, reclining in an armchair. The pencil draft he sent straight to the printers. They supplied him with a considerable number of galley proofs, which he would then distribute to his advisers and critics for comment and amendment. As he published on his own account, Macmillan & Co., the 'publishers' (in reality they were distributors), could not object to the expense of Keynes' method of operating. They came out of Keynes' profit (Macmillan & Co. merely received a commission). Keynes' object was to simplify the process of circulating drafts; and eventually to secure good sales by fixing the retail price lower than would Macmillan & Co.

The advantages of self-publication can be seen from Étienne Mantoux's review:

When he published The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money last year at the sensational price of 5 shillings, J. M. Keynes perhaps meant to express a wish for the broadest and earliest possible dissemination of his new ideas.

Chronology

Keynes's work on the General Theory began as soon as his Treatise on Money had been published in 1930. He was already dissatisfied with what he had written and wanted to extend the scope of his theory to output and employment. By September 1932 he was able to write to his mother: 'I have written nearly a third of my new book on monetary theory'.

In autumn 1932 he delivered lectures at Cambridge under the title 'the monetary theory of production' whose content was close to the Treatise except in giving prominence to a liquidity preference theory of interest. There was no consumption function and no theory of effective demand. Wage rates were discussed in a criticism of Pigou.

In autumn 1933 Keynes's lectures were much closer to the General Theory, including the consumption function, effective demand, and a statement of 'the inability of workers to bargain for a market-clearing real wage in a monetary economy'. All that was missing was a theory of investment.

By spring 1934 Chapter 12 was in its final form.

His lectures in autumn of that year bore the title 'the general theory of employment'. In these lectures Keynes presented the marginal efficiency of capital in much the same form as it took in Chapter 11, his 'basic chapter' as Kahn called it. He gave a talk on the same subject to economists at Oxford in February 1935.

This was the final building block of the General Theory. The book was finished in December 1935 and published in February 1936.

Observations on its readability

Keynes was an associate of Lytton Strachey and shared much of his outlook. Many economists found General Theory difficult to read, with Étienne Mantoux calling it obscure, Frank Knight calling it difficult to follow, Michel DeVroey commenting that "many passages of his book were almost indecipherable", and Paul Samuelson calling the analysis "unpalatable" and incomprehensible. Raúl Rojas dissents, saying that "obscure neo-classical reinterpretations" are "completely pointless since Keynes' book is so readable".

Inessential chapters

Chapter 16: Sundry observations on the nature of capital

§I: Say's Law

Keynes reiterates his denial that an act of saving constitutes an act of investment. A formulation of classical macroeconomics in three equations was given above as follows:

- y'(N) = W/p i (r) = s(y(N),r) M̂ = p·y(N) / V(r)

The role of Say's Law in Keynes's interpretation of them can be seen if we split the second equation into two components:

- i (r) = id(y(N),r) id(y(N),r) = s(y(N),r)

the first of which asserts the equilibrium between investment and its corresponding demand, and the second of which identifies the demand for investment with the desired level of saving. In rejecting the second component Keynes denies that the total demand for goods in an economy is identical with its total income – i.e. that supply creates its own demand – and is therefore able to make their equality an equilibrium condition.

Chapter 16 contains a few statements in support of the view that saving does not necessarily add to the demand for capital goods.

An act of individual saving means – so to speak – a decision not to have dinner to-day. But it does not necessitate a decision to have dinner or to buy a pair of boots a week hence or a year hence or to consume any specified thing at any specified date.

... an individual decision to save does not, in actual fact, involve the placing of any specific forward order for consumption, but merely the cancellation of a present order.

He adds that:

The absurd, though almost universal, idea that an act of individual saving is just as good for effective demand as an act of individual consumption, has been fostered by the fallacy... that an increased desire to hold wealth, being much the same thing as an increased desire to hold investments, must, by increasing the demand for investments, provide a stimulus to their production; so that current investment is promoted by individual saving to the same extent as present consumption is diminished.

It is in this chapter that Keynes mentions "the ownership of money and debts" as "an alternative to the ownership of real capital-assets" (p212). On the same page he draws attention to what he considers to be the error of...

... believing that the owner of wealth desires a capital-asset as such, whereas what he really desires is its prospective yield.

§II–IV: The declining yield of capital

Keynes argues that the value of capital derives from its scarcity and sympathises with 'the pre-classical doctrine that everything is produced by labour' (p213). The preference for direct over roundabout processes will depend on the rate of interest.

He wonders what would happen to 'a society which finds itself so well equipped with capital that its marginal efficiency is zero' while money provides a safe outlet for savings. He does not consider this hypothesis far-fetched: on the contrary...

... a properly run community... ought to be able to bring down the marginal efficiency of capital in equilibrium approximately to zero within a single generation...

He asserts that...

... the position of equilibrium, under conditions of laissez-faire, will be one in which employment is low enough and the standard of life sufficiently miserable to bring savings to zero'.

The misery does not depend on any assumption of static wages. If the return to capital falls to zero then according to Keynes's theory there will be no investment, and income must collapse to the point at which the propensity to save disappears. However his conclusions are not pessimistic because he postulates that steps may be taken to adjust the interest rate to ensure full employment (p220), that 'enormous social changes would result' and that 'this may be the most sensible way of getting rid of many of the objectionable features of capitalism' (p221).

Chapter 17: The essential properties of interest and money

Keynes begins by defining 'own rates of interest'. If the market price for purchasing the commitment to supply a bushel of wheat every year in perpetuity was the price of 50 bushels, then the 'wheat rate of interest' would be 2%. He then tries to find the property which justifies us in regarding the money rate as the true rate. His arguments didn't satisfy his supporters who accepted Pigou's contention that it makes no difference which rate is used.

Hazlitt went further, considering the very concept of an own rate of interest to be 'one of the most incredible' of the 'confusions in the General Theory.

Book V: Money-wages and prices

Chapter 23: Notes on mercantilism

In §I–IV Keynes gives a sympathetic notice to the 17th century mercantilists who, like himself, believed interest to be a monetary phenomenon and saw high interest rates as harmful. He accepts their conclusion that in principle export restrictions may prevent the flow of money abroad and lead to economic advantages at home.

For similar reasons Keynes sees justice in scholastic prohibitions of usury. He remarks in §V that Adam Smith had supported a maximum legal rate of interest. Smith's reasoning – certainly surprising from the proponent of the 'invisible hand' of markets – was based on a fear that a high rate of interest would lead to loans being cornered by spendthrifts and get-rich-quick 'projectors'.

§VI is devoted to the theories of 'the strange, unduly neglected prophet Silvio Gesell' who had proposed a system of 'stamped money' to artificially increase the carrying costs of money. 'The idea behind stamped money is sound', says Keynes, but subject to technical difficulties, one of which is the existence of other outlets for liquidity preference such as jewellery and formerly land. It is interesting that Keynes considered durable assets to be as much a problem as banknotes: even when they satisfy the same motives for ownership, they lack the property that wages are fixed in terms of them.

Keynes's final brief survey in §VII is of theories of underconsumption. Bernard Mandeville in the early 18th century and Hobson and Mummery in the late 19th were amongst those who believed that private thrift was the source of public poverty rather than riches.

Chapter 24: Concluding notes on social philosophy

Saving does not, in Keynes's view, engender investment, but rather impedes it by reducing the likely return to capital: "One of the chief social justifications of great inequality of wealth is, therefore, removed" (p373).

It would not be difficult to increase the stock of capital up to a point where its marginal efficiency had fallen to a very low figure... [This] would mean the euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital... it will still be possible for communal saving through the agency of the State to be maintained at a level which will allow the growth of capital up to the point where it ceases to be scarce... And it would remain for separate decision on what scale and by what means it is right and reasonable to call on the living generation to restrict their consumption, so as to establish in course of time, a state of full investment for their successors.

In some other respects the foregoing theory is moderately conservative in its implications... Thus, apart from the necessity of central controls to bring about an adjustment between the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest, there is no more reason to socialise economic life than there was before.

... the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back... But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.

Reception

Keynes did not set out a detailed policy program in The General Theory, but he went on in practice to place great emphasis on the reduction of long-term interest rates and the reform of the international monetary system as structural measures needed to encourage both investment and consumption by the private sector. Paul Samuelson said that the General Theory "caught most economists under the age of 35 with the unexpected virulence of a disease first attacking and decimating an isolated tribe of South Sea islanders."

Praise

Many of the innovations introduced by The General Theory continue to be central to modern macroeconomics. For instance, the idea that recessions reflect inadequate aggregate demand and that Say's Law (in Keynes's formulation, that "supply creates its own demand") does not hold in a monetary economy. President Richard Nixon famously said in 1971 (ironically, shortly before Keynesian economics fell out of fashion) that "We are all Keynesians now", a phrase often repeated by Nobel laureate Paul Krugman (but originating with anti-Keynesian economist Milton Friedman, said in a way different from Krugman's interpretation). Nevertheless, starting with Axel Leijonhufvud, this view of Keynesian economics came under increasing challenge and scrutiny and has now divided into two main camps.

The majority new consensus view, found in most current text-books and taught in all universities, is New Keynesian economics, which accepts the neoclassical concept of long-run equilibrium but allows a role for aggregate demand in the short run. New Keynesian economists pride themselves on providing microeconomic foundations for the sticky prices and wages assumed by Old Keynesian economics. They do not regard The General Theory itself as helpful to further research. The minority view is represented by post-Keynesian economists, all of whom accept Keynes's fundamental critique of the neoclassical concept of long-run equilibrium, and some of whom think The General Theory has yet to be properly understood and repays further study.

In 2011, the book was placed on Time's top 100 non-fiction books written in English since 1923.

Criticisms

From the outset there has been controversy over what Keynes really meant. Many early reviews were highly critical. The success of what came to be known as "neoclassical synthesis" Keynesian economics owed a great deal to the Harvard economist Alvin Hansen and MIT economist Paul Samuelson as well as to the Oxford economist John Hicks. Hansen and Samuelson offered a lucid explanation of Keynes's theory of aggregate demand with their elegant 45° Keynesian cross diagram while Hicks created the IS-LM diagram. Both of these diagrams can still be found in textbooks. Post-Keynesians argue that the neoclassical Keynesian model is completely distorting and misinterpreting Keynes' original meaning.

Just as the reception of The General Theory was encouraged by the 1930s experience of mass unemployment, its fall from favour was associated with the 'stagflation' of the 1970s. Although few modern economists would disagree with the need for at least some intervention, policies such as labour market flexibility are underpinned by the neoclassical notion of equilibrium in the long run. Although Keynes explicitly addresses inflation, The General Theory does not treat it as an essentially monetary phenomenon or suggest that control of the money supply or interest rates is the key remedy for inflation, unlike neoclassical theory.

Lastly, Keynes' economic theory was criticized by Marxian economists, who said that Keynes ideas, while good intentioned, cannot work in the long run due to the contradictions in capitalism. A couple of these, that Marxians point to are the idea of full employment, which is seen as impossible under private capitalism; and the idea that government can encourage capital investment through government spending, when in reality government spending could be a net loss on profits.