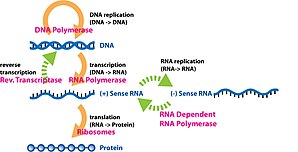

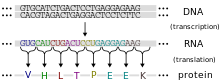

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein-coding genes such as transfer RNA (tRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA), the product is a functional non-coding RNA. Gene expression is summarized in the central dogma of molecular biology first formulated by Francis Crick in 1958, further developed in his 1970 article, and expanded by the subsequent discoveries of reverse transcription and RNA replication.

The process of gene expression is used by all known life—eukaryotes (including multicellular organisms), prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), and utilized by viruses—to generate the macromolecular machinery for life.

In genetics, gene expression is the most fundamental level at which the genotype gives rise to the phenotype, i.e. observable trait. The genetic information stored in DNA represents the genotype, whereas the phenotype results from the "interpretation" of that information. Such phenotypes are often expressed by the synthesis of proteins that control the organism's structure and development, or that act as enzymes catalyzing specific metabolic pathways.

All steps in the gene expression process may be modulated (regulated), including the transcription, RNA splicing, translation, and post-translational modification of a protein. Regulation of gene expression gives control over the timing, location, and amount of a given gene product (protein or ncRNA) present in a cell and can have a profound effect on the cellular structure and function. Regulation of gene expression is the basis for cellular differentiation, development, morphogenesis and the versatility and adaptability of any organism. Gene regulation may therefore serve as a substrate for evolutionary change.

Mechanism

Transcription

The production of a RNA copy from a DNA strand is called transcription, and is performed by RNA polymerases, which add one ribonucleotide at a time to a growing RNA strand as per the complementarity law of the nucleotide bases. This RNA is complementary to the template 3′ → 5′ DNA strand, with the exception that thymines (T) are replaced with uracils (U) in the RNA.

In prokaryotes, transcription is carried out by a single type of RNA polymerase, which needs to bind a DNA sequence called a Pribnow box with the help of the sigma factor protein (σ factor) to start transcription. In eukaryotes, transcription is performed in the nucleus by three types of RNA polymerases, each of which needs a special DNA sequence called the promoter and a set of DNA-binding proteins—transcription factors—to initiate the process (see regulation of transcription below). RNA polymerase I is responsible for transcription of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcribes all protein-coding genes but also some non-coding RNAs (e.g., snRNAs, snoRNAs or long non-coding RNAs). RNA polymerase III transcribes 5S rRNA, transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and some small non-coding RNAs (e.g., 7SK). Transcription ends when the polymerase encounters a sequence called the terminator.

mRNA processing

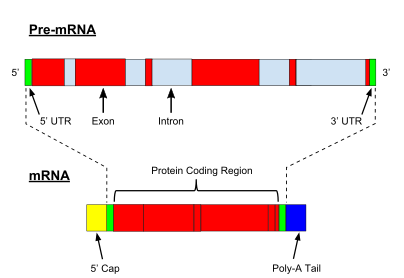

While transcription of prokaryotic protein-coding genes creates messenger RNA (mRNA) that is ready for translation into protein, transcription of eukaryotic genes leaves a primary transcript of RNA (pre-RNA), which first has to undergo a series of modifications to become a mature RNA. Types and steps involved in the maturation processes vary between coding and non-coding preRNAs; i.e. even though preRNA molecules for both mRNA and tRNA undergo splicing, the steps and machinery involved are different. The processing of non-coding RNA is described below (non-coring RNA maturation).

The processing of premRNA include 5′ capping, which is set of enzymatic reactions that add 7-methylguanosine (m7G) to the 5′ end of pre-mRNA and thus protect the RNA from degradation by exonucleases. The m7G cap is then bound by cap binding complex heterodimer (CBC20/CBC80), which aids in mRNA export to cytoplasm and also protect the RNA from decapping.

Another modification is 3′ cleavage and polyadenylation. They occur if polyadenylation signal sequence (5′- AAUAAA-3′) is present in pre-mRNA, which is usually between protein-coding sequence and terminator. The pre-mRNA is first cleaved and then a series of ~200 adenines (A) are added to form poly(A) tail, which protects the RNA from degradation. The poly(A) tail is bound by multiple poly(A)-binding proteins (PABPs) necessary for mRNA export and translation re-initiation. In the inverse process of deadenylation, poly(A) tails are shortened by the CCR4-Not 3′-5′ exonuclease, which often leads to full transcript decay.

A very important modification of eukaryotic pre-mRNA is RNA splicing. The majority of eukaryotic pre-mRNAs consist of alternating segments called exons and introns. During the process of splicing, an RNA-protein catalytical complex known as spliceosome catalyzes two transesterification reactions, which remove an intron and release it in form of lariat structure, and then splice neighbouring exons together. In certain cases, some introns or exons can be either removed or retained in mature mRNA. This so-called alternative splicing creates series of different transcripts originating from a single gene. Because these transcripts can be potentially translated into different proteins, splicing extends the complexity of eukaryotic gene expression and the size of a species proteome.

Extensive RNA processing may be an evolutionary advantage made possible by the nucleus of eukaryotes. In prokaryotes, transcription and translation happen together, whilst in eukaryotes, the nuclear membrane separates the two processes, giving time for RNA processing to occur.

Non-coding RNA maturation

In most organisms non-coding genes (ncRNA) are transcribed as precursors that undergo further processing. In the case of ribosomal RNAs (rRNA), they are often transcribed as a pre-rRNA that contains one or more rRNAs. The pre-rRNA is cleaved and modified (2′-O-methylation and pseudouridine formation) at specific sites by approximately 150 different small nucleolus-restricted RNA species, called snoRNAs. SnoRNAs associate with proteins, forming snoRNPs. While snoRNA part basepair with the target RNA and thus position the modification at a precise site, the protein part performs the catalytical reaction. In eukaryotes, in particular a snoRNP called RNase, MRP cleaves the 45S pre-rRNA into the 28S, 5.8S, and 18S rRNAs. The rRNA and RNA processing factors form large aggregates called the nucleolus.

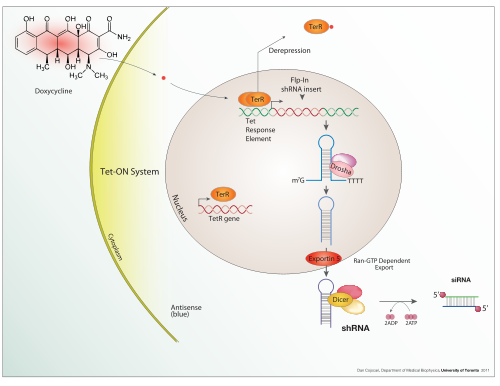

In the case of transfer RNA (tRNA), for example, the 5′ sequence is removed by RNase P, whereas the 3′ end is removed by the tRNase Z enzyme and the non-templated 3′ CCA tail is added by a nucleotidyl transferase. In the case of micro RNA (miRNA), miRNAs are first transcribed as primary transcripts or pri-miRNA with a cap and poly-A tail and processed to short, 70-nucleotide stem-loop structures known as pre-miRNA in the cell nucleus by the enzymes Drosha and Pasha. After being exported, it is then processed to mature miRNAs in the cytoplasm by interaction with the endonuclease Dicer, which also initiates the formation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), composed of the Argonaute protein.

Even snRNAs and snoRNAs themselves undergo series of modification before they become part of functional RNP complex. This is done either in the nucleoplasm or in the specialized compartments called Cajal bodies. Their bases are methylated or pseudouridinilated by a group of small Cajal body-specific RNAs (scaRNAs), which are structurally similar to snoRNAs.

RNA export

In eukaryotes most mature RNA must be exported to the cytoplasm from the nucleus. While some RNAs function in the nucleus, many RNAs are transported through the nuclear pores and into the cytosol. Export of RNAs requires association with specific proteins known as exportins. Specific exportin molecules are responsible for the export of a given RNA type. mRNA transport also requires the correct association with Exon Junction Complex (EJC), which ensures that correct processing of the mRNA is completed before export. In some cases RNAs are additionally transported to a specific part of the cytoplasm, such as a synapse; they are then towed by motor proteins that bind through linker proteins to specific sequences (called "zipcodes") on the RNA.

Translation

For some RNA (non-coding RNA) the mature RNA is the final gene product. In the case of messenger RNA (mRNA) the RNA is an information carrier coding for the synthesis of one or more proteins. mRNA carrying a single protein sequence (common in eukaryotes) is monocistronic whilst mRNA carrying multiple protein sequences (common in prokaryotes) is known as polycistronic.

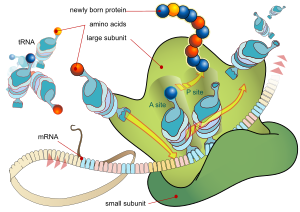

Every mRNA consists of three parts: a 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR), a protein-coding region or open reading frame (ORF), and a 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). The coding region carries information for protein synthesis encoded by the genetic code to form triplets. Each triplet of nucleotides of the coding region is called a codon and corresponds to a binding site complementary to an anticodon triplet in transfer RNA. Transfer RNAs with the same anticodon sequence always carry an identical type of amino acid. Amino acids are then chained together by the ribosome according to the order of triplets in the coding region. The ribosome helps transfer RNA to bind to messenger RNA and takes the amino acid from each transfer RNA and makes a structure-less protein out of it. Each mRNA molecule is translated into many protein molecules, on average ~2800 in mammals.

In prokaryotes translation generally occurs at the point of transcription (co-transcriptionally), often using a messenger RNA that is still in the process of being created. In eukaryotes translation can occur in a variety of regions of the cell depending on where the protein being written is supposed to be. Major locations are the cytoplasm for soluble cytoplasmic proteins and the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum for proteins that are for export from the cell or insertion into a cell membrane. Proteins that are supposed to be expressed at the endoplasmic reticulum are recognised part-way through the translation process. This is governed by the signal recognition particle—a protein that binds to the ribosome and directs it to the endoplasmic reticulum when it finds a signal peptide on the growing (nascent) amino acid chain.

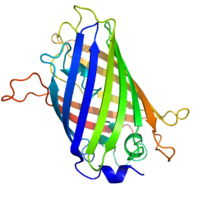

Folding

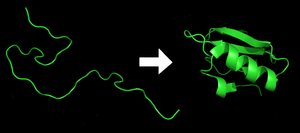

Each protein exists as an unfolded polypeptide or random coil when translated from a sequence of mRNA into a linear chain of amino acids. This polypeptide lacks any developed three-dimensional structure (the left hand side of the neighboring figure). The polypeptide then folds into its characteristic and functional three-dimensional structure from a random coil. Amino acids interact with each other to produce a well-defined three-dimensional structure, the folded protein (the right hand side of the figure) known as the native state. The resulting three-dimensional structure is determined by the amino acid sequence (Anfinsen's dogma).

The correct three-dimensional structure is essential to function, although some parts of functional proteins may remain unfolded. Failure to fold into the intended shape usually produces inactive proteins with different properties including toxic prions. Several neurodegenerative and other diseases are believed to result from the accumulation of misfolded proteins. Many allergies are caused by the folding of the proteins, for the immune system does not produce antibodies for certain protein structures.

Enzymes called chaperones assist the newly formed protein to attain (fold into) the 3-dimensional structure it needs to function. Similarly, RNA chaperones help RNAs attain their functional shapes. Assisting protein folding is one of the main roles of the endoplasmic reticulum in eukaryotes.

Translocation

Secretory proteins of eukaryotes or prokaryotes must be translocated to enter the secretory pathway. Newly synthesized proteins are directed to the eukaryotic Sec61 or prokaryotic SecYEG translocation channel by signal peptides. The efficiency of protein secretion in eukaryotes is very dependent on the signal peptide which has been used.

Protein transport

Many proteins are destined for other parts of the cell than the cytosol and a wide range of signalling sequences or (signal peptides) are used to direct proteins to where they are supposed to be. In prokaryotes this is normally a simple process due to limited compartmentalisation of the cell. However, in eukaryotes there is a great variety of different targeting processes to ensure the protein arrives at the correct organelle.

Not all proteins remain within the cell and many are exported, for example, digestive enzymes, hormones and extracellular matrix proteins. In eukaryotes the export pathway is well developed and the main mechanism for the export of these proteins is translocation to the endoplasmic reticulum, followed by transport via the Golgi apparatus.

Regulation of gene expression

Regulation of gene expression refers to the control of the amount and timing of appearance of the functional product of a gene. Control of expression is vital to allow a cell to produce the gene products it needs when it needs them; in turn, this gives cells the flexibility to adapt to a variable environment, external signals, damage to the cell, and other stimuli. More generally, gene regulation gives the cell control over all structure and function, and is the basis for cellular differentiation, morphogenesis and the versatility and adaptability of any organism.

Numerous terms are used to describe types of genes depending on how they are regulated; these include:

- A constitutive gene is a gene that is transcribed continually as opposed to a facultative gene, which is only transcribed when needed.

- A housekeeping gene is a gene that is required to maintain basic cellular function and so is typically expressed in all cell types of an organism. Examples include actin, GAPDH and ubiquitin. Some housekeeping genes are transcribed at a relatively constant rate and these genes can be used as a reference point in experiments to measure the expression rates of other genes.

- A facultative gene is a gene only transcribed when needed as opposed to a constitutive gene.

- An inducible gene is a gene whose expression is either responsive to environmental change or dependent on the position in the cell cycle.

Any step of gene expression may be modulated, from the DNA-RNA transcription step to post-translational modification of a protein. The stability of the final gene product, whether it is RNA or protein, also contributes to the expression level of the gene—an unstable product results in a low expression level. In general gene expression is regulated through changes in the number and type of interactions between molecules that collectively influence transcription of DNA and translation of RNA.

Some simple examples of where gene expression is important are:

- Control of insulin expression so it gives a signal for blood glucose regulation.

- X chromosome inactivation in female mammals to prevent an "overdose" of the genes it contains.

- Cyclin expression levels control progression through the eukaryotic cell cycle.

Transcriptional regulation

Regulation of transcription can be broken down into three main routes of influence; genetic (direct interaction of a control factor with the gene), modulation interaction of a control factor with the transcription machinery and epigenetic (non-sequence changes in DNA structure that influence transcription).

Direct interaction with DNA is the simplest and the most direct method by which a protein changes transcription levels. Genes often have several protein binding sites around the coding region with the specific function of regulating transcription. There are many classes of regulatory DNA binding sites known as enhancers, insulators and silencers. The mechanisms for regulating transcription are very varied, from blocking key binding sites on the DNA for RNA polymerase to acting as an activator and promoting transcription by assisting RNA polymerase binding.

The activity of transcription factors is further modulated by intracellular signals causing protein post-translational modification including phosphorylated, acetylated, or glycosylated. These changes influence a transcription factor's ability to bind, directly or indirectly, to promoter DNA, to recruit RNA polymerase, or to favor elongation of a newly synthesized RNA molecule.

The nuclear membrane in eukaryotes allows further regulation of transcription factors by the duration of their presence in the nucleus, which is regulated by reversible changes in their structure and by binding of other proteins. Environmental stimuli or endocrine signals may cause modification of regulatory proteins eliciting cascades of intracellular signals, which result in regulation of gene expression.

More recently it has become apparent that there is a significant influence of non-DNA-sequence specific effects on transcription. These effects are referred to as epigenetic and involve the higher order structure of DNA, non-sequence specific DNA binding proteins and chemical modification of DNA. In general epigenetic effects alter the accessibility of DNA to proteins and so modulate transcription.

In eukaryotes the structure of chromatin, controlled by the histone code, regulates access to DNA with significant impacts on the expression of genes in euchromatin and heterochromatin areas.

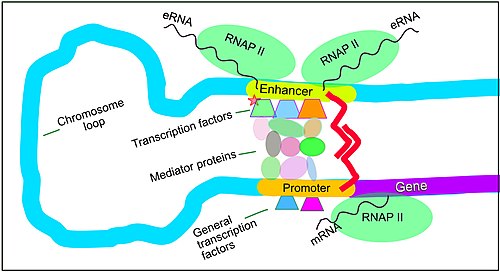

Enhancers, transcription factors, Mediator complex and DNA loops in mammalian transcription

Gene expression in mammals is regulated by many cis-regulatory elements, including core promoters and promoter-proximal elements that are located near the transcription start sites of genes, upstream on the DNA (towards the 5' region of the sense strand). Other important cis-regulatory modules are localized in DNA regions that are distant from the transcription start sites. These include enhancers, silencers, insulators and tethering elements. Among this constellation of elements, enhancers and their associated transcription factors have a leading role in the regulation of gene expression.

Enhancers are regions of the genome that are major gene-regulatory elements. Enhancers control cell-type-specific gene expression programs, most often by looping through long distances to come in physical proximity with the promoters of their target genes. Multiple enhancers, each often at tens or hundred of thousands of nucleotides distant from their target genes, loop to their target gene promoters and coordinate with each other to control expression of their common target gene.

The schematic illustration at the left shows an enhancer looping around to come into close physical proximity with the promoter of a target gene. The loop is stabilized by a dimer of a connector protein (e.g. dimer of CTCF or YY1), with one member of the dimer anchored to its binding motif on the enhancer and the other member anchored to its binding motif on the promoter (represented by the red zigzags in the illustration). Several cell function specific transcription factors (there are about 1,600 transcription factors in a human cell) generally bind to specific motifs on an enhancer and a small combination of these enhancer-bound transcription factors, when brought close to a promoter by a DNA loop, govern level of transcription of the target gene. Mediator (a complex usually consisting of about 26 proteins in an interacting structure) communicates regulatory signals from enhancer DNA-bound transcription factors directly to the RNA polymerase II (pol II) enzyme bound to the promoter.

Enhancers, when active, are generally transcribed from both strands of DNA with RNA polymerases acting in two different directions, producing two eRNAs as illustrated in the Figure. An inactive enhancer may be bound by an inactive transcription factor. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor may activate it and that activated transcription factor may then activate the enhancer to which it is bound (see small red star representing phosphorylation of transcription factor bound to enhancer in the illustration). An activated enhancer begins transcription of its RNA before activating transcription of messenger RNA from its target gene.

DNA methylation and demethylation in transcriptional regulation

DNA methylation is a widespread mechanism for epigenetic influence on gene expression and is seen in bacteria and eukaryotes and has roles in heritable transcription silencing and transcription regulation. Methylation most often occurs on a cytosine (see Figure). Methylation of cytosine primarily occurs in dinucleotide sequences where a cytosine is followed by a guanine, a CpG site. The number of CpG sites in the human genome is about 28 million. Depending on the type of cell, about 70% of the CpG sites have a methylated cytosine.

Methylation of cytosine in DNA has a major role in regulating gene expression. Methylation of CpGs in a promoter region of a gene usually represses gene transcription while methylation of CpGs in the body of a gene increases expression. TET enzymes play a central role in demethylation of methylated cytosines. Demethylation of CpGs in a gene promoter by TET enzyme activity increases transcription of the gene.

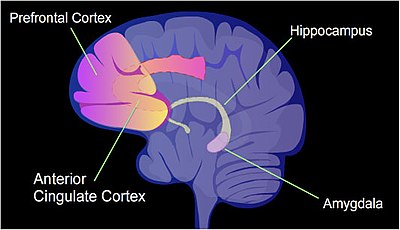

Transcriptional regulation in learning and memory

In a rat, contextual fear conditioning (CFC) is a painful learning experience. Just one episode of CFC can result in a life-long fearful memory. After an episode of CFC, cytosine methylation is altered in the promoter regions of about 9.17% of all genes in the hippocampus neuron DNA of a rat. The hippocampus is where new memories are initially stored. After CFC about 500 genes have increased transcription (often due to demethylation of CpG sites in a promoter region) and about 1,000 genes have decreased transcription (often due to newly formed 5-methylcytosine at CpG sites in a promoter region). The pattern of induced and repressed genes within neurons appears to provide a molecular basis for forming the first transient memory of this training event in the hippocampus of the rat brain.

In particular, the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene (BDNF) is known as a "learning gene." After CFC there was upregulation of BDNF gene expression, related to decreased CpG methylation of certain internal promoters of the gene, and this was correlated with learning.

Transcriptional regulation in cancer

The majority of gene promoters contain a CpG island with numerous CpG sites. When many of a gene's promoter CpG sites are methylated the gene becomes silenced. Colorectal cancers typically have 3 to 6 driver mutations and 33 to 66 hitchhiker or passenger mutations. However, transcriptional silencing may be of more importance than mutation in causing progression to cancer. For example, in colorectal cancers about 600 to 800 genes are transcriptionally silenced by CpG island methylation. Transcriptional repression in cancer can also occur by other epigenetic mechanisms, such as altered expression of microRNAs. In breast cancer, transcriptional repression of BRCA1 may occur more frequently by over-expressed microRNA-182 than by hypermethylation of the BRCA1 promoter (see Low expression of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancers).

Post-transcriptional regulation

In eukaryotes, where export of RNA is required before translation is possible, nuclear export is thought to provide additional control over gene expression. All transport in and out of the nucleus is via the nuclear pore and transport is controlled by a wide range of importin and exportin proteins.

Expression of a gene coding for a protein is only possible if the messenger RNA carrying the code survives long enough to be translated. In a typical cell, an RNA molecule is only stable if specifically protected from degradation. RNA degradation has particular importance in regulation of expression in eukaryotic cells where mRNA has to travel significant distances before being translated. In eukaryotes, RNA is stabilised by certain post-transcriptional modifications, particularly the 5′ cap and poly-adenylated tail.

Intentional degradation of mRNA is used not just as a defence mechanism from foreign RNA (normally from viruses) but also as a route of mRNA destabilisation. If an mRNA molecule has a complementary sequence to a small interfering RNA then it is targeted for destruction via the RNA interference pathway.

Three prime untranslated regions and microRNAs

Three prime untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) often contain regulatory sequences that post-transcriptionally influence gene expression. Such 3′-UTRs often contain both binding sites for microRNAs (miRNAs) as well as for regulatory proteins. By binding to specific sites within the 3′-UTR, miRNAs can decrease gene expression of various mRNAs by either inhibiting translation or directly causing degradation of the transcript. The 3′-UTR also may have silencer regions that bind repressor proteins that inhibit the expression of a mRNA.

The 3′-UTR often contains microRNA response elements (MREs). MREs are sequences to which miRNAs bind. These are prevalent motifs within 3′-UTRs. Among all regulatory motifs within the 3′-UTRs (e.g. including silencer regions), MREs make up about half of the motifs.

As of 2014, the miRBase web site, an archive of miRNA sequences and annotations, listed 28,645 entries in 233 biologic species. Of these, 1,881 miRNAs were in annotated human miRNA loci. miRNAs were predicted to have an average of about four hundred target mRNAs (affecting expression of several hundred genes). Friedman et al. estimate that >45,000 miRNA target sites within human mRNA 3′UTRs are conserved above background levels, and >60% of human protein-coding genes have been under selective pressure to maintain pairing to miRNAs.

Direct experiments show that a single miRNA can reduce the stability of hundreds of unique mRNAs. Other experiments show that a single miRNA may repress the production of hundreds of proteins, but that this repression often is relatively mild (less than 2-fold).

The effects of miRNA dysregulation of gene expression seem to be important in cancer. For instance, in gastrointestinal cancers, nine miRNAs have been identified as epigenetically altered and effective in down regulating DNA repair enzymes.

The effects of miRNA dysregulation of gene expression also seem to be important in neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and autism spectrum disorders.

Translational regulation

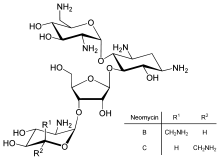

Direct regulation of translation is less prevalent than control of transcription or mRNA stability but is occasionally used. Inhibition of protein translation is a major target for toxins and antibiotics, so they can kill a cell by overriding its normal gene expression control. Protein synthesis inhibitors include the antibiotic neomycin and the toxin ricin.

Post-translational modifications

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are covalent modifications to proteins. Like RNA splicing, they help to significantly diversify the proteome. These modifications are usually catalyzed by enzymes. Additionally, processes like covalent additions to amino acid side chain residues can often be reversed by other enzymes. However, some, like the proteolytic cleavage of the protein backbone, are irreversible.

PTMs play many important roles in the cell. For example, phosphorylation is primarily involved in activating and deactivating proteins and in signaling pathways. PTMs are involved in transcriptional regulation: an important function of acetylation and methylation is histone tail modification, which alters how accessible DNA is for transcription. They can also be seen in the immune system, where glycosylation plays a key role. One type of PTM can initiate another type of PTM, as can be seen in how ubiquitination tags proteins for degradation through proteolysis. Proteolysis, other than being involved in breaking down proteins, is also important in activating and deactivating them, and in regulating biological processes such as DNA transcription and cell death.

Measurement

Measuring gene expression is an important part of many life sciences, as the ability to quantify the level at which a particular gene is expressed within a cell, tissue or organism can provide a lot of valuable information. For example, measuring gene expression can:

- Identify viral infection of a cell (viral protein expression).

- Determine an individual's susceptibility to cancer (oncogene expression).

- Find if a bacterium is resistant to penicillin (beta-lactamase expression).

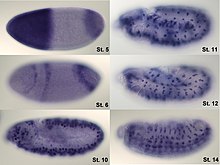

Similarly, the analysis of the location of protein expression is a powerful tool, and this can be done on an organismal or cellular scale. Investigation of localization is particularly important for the study of development in multicellular organisms and as an indicator of protein function in single cells. Ideally, measurement of expression is done by detecting the final gene product (for many genes, this is the protein); however, it is often easier to detect one of the precursors, typically mRNA and to infer gene-expression levels from these measurements.

mRNA quantification

Levels of mRNA can be quantitatively measured by northern blotting, which provides size and sequence information about the mRNA molecules. A sample of RNA is separated on an agarose gel and hybridized to a radioactively labeled RNA probe that is complementary to the target sequence. The radiolabeled RNA is then detected by an autoradiograph. Because the use of radioactive reagents makes the procedure time consuming and potentially dangerous, alternative labeling and detection methods, such as digoxigenin and biotin chemistries, have been developed. Perceived disadvantages of Northern blotting are that large quantities of RNA are required and that quantification may not be completely accurate, as it involves measuring band strength in an image of a gel. On the other hand, the additional mRNA size information from the Northern blot allows the discrimination of alternately spliced transcripts.

Another approach for measuring mRNA abundance is RT-qPCR. In this technique, reverse transcription is followed by quantitative PCR. Reverse transcription first generates a DNA template from the mRNA; this single-stranded template is called cDNA. The cDNA template is then amplified in the quantitative step, during which the fluorescence emitted by labeled hybridization probes or intercalating dyes changes as the DNA amplification process progresses. With a carefully constructed standard curve, qPCR can produce an absolute measurement of the number of copies of original mRNA, typically in units of copies per nanolitre of homogenized tissue or copies per cell. qPCR is very sensitive (detection of a single mRNA molecule is theoretically possible), but can be expensive depending on the type of reporter used; fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes are more expensive than non-specific intercalating fluorescent dyes.

For expression profiling, or high-throughput analysis of many genes within a sample, quantitative PCR may be performed for hundreds of genes simultaneously in the case of low-density arrays. A second approach is the hybridization microarray. A single array or "chip" may contain probes to determine transcript levels for every known gene in the genome of one or more organisms. Alternatively, "tag based" technologies like Serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and RNA-Seq, which can provide a relative measure of the cellular concentration of different mRNAs, can be used. An advantage of tag-based methods is the "open architecture", allowing for the exact measurement of any transcript, with a known or unknown sequence. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) such as RNA-Seq is another approach, producing vast quantities of sequence data that can be matched to a reference genome. Although NGS is comparatively time-consuming, expensive, and resource-intensive, it can identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms, splice-variants, and novel genes, and can also be used to profile expression in organisms for which little or no sequence information is available.

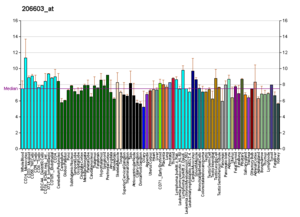

RNA profiles in Wikipedia

Profiles like these are found for almost all proteins listed in Wikipedia. They are generated by organizations such as the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation and the European Bioinformatics Institute. Additional information can be found by searching their databases (for an example of the GLUT4 transporter pictured here, see citation). These profiles indicate the level of DNA expression (and hence RNA produced) of a certain protein in a certain tissue, and are color-coded accordingly in the images located in the Protein Box on the right side of each Wikipedia page.

Protein quantification

For genes encoding proteins, the expression level can be directly assessed by a number of methods with some clear analogies to the techniques for mRNA quantification.

One of the most commonly used methods is to perform a Western blot against the protein of interest. This gives information on the size of the protein in addition to its identity. A sample (often cellular lysate) is separated on a polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a membrane and then probed with an antibody to the protein of interest. The antibody can either be conjugated to a fluorophore or to horseradish peroxidase for imaging and/or quantification. The gel-based nature of this assay makes quantification less accurate, but it has the advantage of being able to identify later modifications to the protein, for example proteolysis or ubiquitination, from changes in size.

mRNA-protein correlation

Quantification of protein and mRNA permits a correlation of the two levels. The question of how well protein levels correlate with their corresponding transcript levels is highly debated and depends on multiple factors. Regulation on each step of gene expression can impact the correlation, as shown for regulation of translation or protein stability. Post-translational factors, such as protein transport in highly polar cells, can influence the measured mRNA-protein correlation as well.

Localisation

Analysis of expression is not limited to quantification; localisation can also be determined. mRNA can be detected with a suitably labelled complementary mRNA strand and protein can be detected via labelled antibodies. The probed sample is then observed by microscopy to identify where the mRNA or protein is.

By replacing the gene with a new version fused to a green fluorescent protein (or similar) marker, expression may be directly quantified in live cells. This is done by imaging using a fluorescence microscope. It is very difficult to clone a GFP-fused protein into its native location in the genome without affecting expression levels so this method often cannot be used to measure endogenous gene expression. It is, however, widely used to measure the expression of a gene artificially introduced into the cell, for example via an expression vector. It is important to note that by fusing a target protein to a fluorescent reporter the protein's behavior, including its cellular localization and expression level, can be significantly changed.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay works by using antibodies immobilised on a microtiter plate to capture proteins of interest from samples added to the well. Using a detection antibody conjugated to an enzyme or fluorophore the quantity of bound protein can be accurately measured by fluorometric or colourimetric detection. The detection process is very similar to that of a Western blot, but by avoiding the gel steps more accurate quantification can be achieved.

Expression system

An expression system is a system specifically designed for the production of a gene product of choice. This is normally a protein although may also be RNA, such as tRNA or a ribozyme. An expression system consists of a gene, normally encoded by DNA, and the molecular machinery required to transcribe the DNA into mRNA and translate the mRNA into protein using the reagents provided. In the broadest sense this includes every living cell but the term is more normally used to refer to expression as a laboratory tool. An expression system is therefore often artificial in some manner. Expression systems are, however, a fundamentally natural process. Viruses are an excellent example where they replicate by using the host cell as an expression system for the viral proteins and genome.

Inducible expression

Doxycycline is also used in "Tet-on" and "Tet-off" tetracycline controlled transcriptional activation to regulate transgene expression in organisms and cell cultures.

In nature

In addition to these biological tools, certain naturally observed configurations of DNA (genes, promoters, enhancers, repressors) and the associated machinery itself are referred to as an expression system. This term is normally used in the case where a gene or set of genes is switched on under well defined conditions, for example, the simple repressor switch expression system in Lambda phage and the lac operator system in bacteria. Several natural expression systems are directly used or modified and used for artificial expression systems such as the Tet-on and Tet-off expression system.

Gene networks

Genes have sometimes been regarded as nodes in a network, with inputs being proteins such as transcription factors, and outputs being the level of gene expression. The node itself performs a function, and the operation of these functions have been interpreted as performing a kind of information processing within cells and determines cellular behavior.

Gene networks can also be constructed without formulating an explicit causal model. This is often the case when assembling networks from large expression data sets. Covariation and correlation of expression is computed across a large sample of cases and measurements (often transcriptome or proteome data). The source of variation can be either experimental or natural (observational). There are several ways to construct gene expression networks, but one common approach is to compute a matrix of all pair-wise correlations of expression across conditions, time points, or individuals and convert the matrix (after thresholding at some cut-off value) into a graphical representation in which nodes represent genes, transcripts, or proteins and edges connecting these nodes represent the strength of association.