| Teenage pregnancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Other names | Teen pregnancy, adolescent pregnancy | ||

| |||

| A US government poster on teen pregnancy. Over 1,100 teenagers, mostly aged 18 or 19, give birth every day in the United States. | |||

| Specialty | Obstetrics | ||

| Symptoms | Pregnancy under the age of 20 | ||

| Complications | |||

| Prevention | |||

| Frequency | 23 million per year (developed world) | ||

| Deaths | Leading cause of death (15 to 19 year old females) | ||

Teenage pregnancy, also known as adolescent pregnancy, is pregnancy in a female under the age of 20. Pregnancy can occur with sexual intercourse after the start of ovulation, which can be before the first menstrual period (menarche) but usually occurs after the onset of periods. In well-nourished girls, the first period usually takes place around the age of 12 or 13.

Pregnant teenagers face many of the same pregnancy related issues as other women. There are additional concerns for those under the age of 15 as they are less likely to be physically developed to sustain a healthy pregnancy or to give birth. For girls aged 15–19, risks are associated more with socioeconomic factors than with the biological effects of age. Risks of low birth weight, premature labor, anemia, and pre-eclampsia are connected to biological age, as they are observed in teen births even after controlling for other risk factors, such as access to prenatal care.

Teenage pregnancies are associated with social issues, including lower educational levels and poverty. Teenage pregnancy in developed countries is usually outside of marriage and is often associated with a social stigma. Teenage pregnancy in developing countries often occurs within marriage and half are planned. However, in these societies, early pregnancy may combine with malnutrition and poor health care to cause medical problems. When used in combination, educational interventions and access to birth control can reduce unintended teenage pregnancies.

In 2015, about 47 females per 1,000 had children well under the age of 20. Rates are higher in Africa and lower in Asia. In the developing world about 2.5 million females under the age of 16 and 16 million females 15 to 19 years old have children each year. Another 3.9 million have abortions. It is more common in rural than urban areas. Worldwide, complications related to pregnancy are the most common cause of death among females 15 to 19 years old.

Definition

The age of the mother is determined by the easily verified date when the pregnancy ends, not by the estimated date of conception. Consequently, the statistics do not include pregnancies that began at age 19, but that ended on or after the woman's 20th birthday. Similarly, statistics on the mother's marital status are determined by whether she is married at the end of the pregnancy, not at the time of conception.

History

Teenage pregnancy (with conceptions normally involving girls between age 16 and 19), was far more normal in previous centuries, and common in developed countries in the 20th century. Among Norwegian women born in the early 1950s, nearly a quarter became teenage mothers by the early 1970s. However, the rates have steadily declined throughout the developed world since that 20th century peak. Among those born in Norway in the late 1970s, less than 10% became teenage mothers, and rates have fallen since then.

In the United States, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996 included the objective of reducing the number of young Black and Latina single mothers on welfare, which became the foundation for teenage pregnancy prevention in the United States and the founding of the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, now known as Power to Decide.

Effects

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), "Pregnancies among girls less than 18 years of age have irreparable consequences. It violates the rights of girls, with life-threatening consequences in terms of sexual and reproductive health, and poses high development costs for communities, particularly in perpetuating the cycle of poverty." Health consequences include not yet being physically ready for pregnancy and childbirth leading to complications and malnutrition as the majority of adolescents tend to come from lower-income households. The risk of maternal death for girls under age 15 in low and middle income countries is higher than for women in their twenties. Teenage pregnancy also affects girls' education and income potential as many are forced to drop out of school which ultimately threatens future opportunities and economic prospects.

Several studies have examined the socioeconomic, medical, and psychological impact of pregnancy and parenthood in teens. Life outcomes for teenage mothers and their children vary; other factors, such as poverty or social support, may be more important than the age of the mother at the birth. Many solutions to counteract the more negative findings have been proposed. Teenage parents who can rely on family and community support, social services and child-care support are more likely to continue their education and get higher paying jobs as they progress with their education.

A holistic approach is required in order to address teenage pregnancy. This means not focusing on changing the behaviour of girls but addressing the underlying reasons of adolescent pregnancy such as poverty, gender inequality, social pressures and coercion. This approach should include "providing age-appropriate comprehensive sexuality education for all young people, investing in girls' education, preventing child marriage, sexual violence and coercion, building gender-equitable societies by empowering girls and engaging men and boys and ensuring adolescents' access to sexual and reproductive health information as well as services that welcome them and facilitate their choices".

In the United States one third of high school students reported being sexually active. In 2011–2013, 79% of females reported using birth control. Teenage pregnancy puts young women at risk for health issues, economic, social and financial issues.

Teenager

Being a young mother in a first world country can affect one's education. Teen mothers are more likely to drop out of high school. One study in 2001 found that women that gave birth during their teens completed secondary-level schooling 10–12% as often and pursued post-secondary education 14–29% as often as women who waited until age 30. Young motherhood in an industrialized country can affect employment and social class. Teenage women who are pregnant or mothers are seven times more likely to commit suicide than other teenagers.

According to the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, nearly 1 in 4 teen mothers will experience another pregnancy within two years of having their first. Pregnancy and giving birth significantly increases the chance that these mothers will become high school dropouts and as many as half have to go on welfare. Many teen parents do not have the intellectual or emotional maturity that is needed to provide for another life. Often, these pregnancies are hidden for months resulting in a lack of adequate prenatal care and dangerous outcomes for the babies. Factors that determine which mothers are more likely to have a closely spaced repeat birth include marriage and education: the likelihood decreases with the level of education of the young woman – or her parents – and increases if she gets married.

Child

Early motherhood can affect the psychosocial development of the infant. The children of teen mothers are more likely to be born prematurely with a low birth weight, predisposing them to many other lifelong conditions. Children of teen mothers are at higher risk of intellectual, language, and socio-emotional delays. Developmental disabilities and behavioral issues are increased in children born to teen mothers. One study suggested that adolescent mothers are less likely to stimulate their infant through affectionate behaviors such as touch, smiling, and verbal communication, or to be sensitive and accepting toward his or her needs. Another found that those who had more social support were less likely to show anger toward their children or to rely upon punishment.

Poor academic performance in the children of teenage mothers has also been noted, with many of the children being held back a grade level, scoring lower on standardized tests, and/or failing to graduate from secondary school. Daughters born to adolescent parents are more likely to become teen mothers themselves. Sons born to teenage mothers are three times more likely to serve time in prison.

Medical

Maternal and prenatal health is of particular concern among teens who are pregnant or parenting. The worldwide incidence of premature birth and low birth weight is higher among adolescent mothers. In a rural hospital in West Bengal, teenage mothers between 15 and 19 years old were more likely to have anemia, preterm delivery, and a baby with a lower birth weight than mothers between 20 and 24 years old.

Research indicates that pregnant teens are less likely to receive prenatal care, often seeking it in the third trimester, if at all. The Guttmacher Institute reports that one-third of pregnant teens receive insufficient prenatal care and that their children are more likely to have health issues in childhood or be hospitalized than those born to older women.

In the United States, teenage Latinas who become pregnant face barriers to receiving healthcare because they are the least insured group in the country.

Young mothers who are given high-quality maternity care have significantly healthier babies than those who do not. Many of the health-issues associated with teenage mothers appear to result from lack of access to adequate medical care.

Many pregnant teens are at risk of nutritional deficiencies from poor eating habits common in adolescence, including attempts to lose weight through dieting, skipping meals, food faddism, snacking, and consumption of fast food.

Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy is an even more marked problem among teenagers in developing countries. Complications of pregnancy result in the deaths of an estimated 70,000 teen girls in developing countries each year. Young mothers and their babies are also at greater risk of contracting HIV. The World Health Organization estimates that the risk of death following pregnancy is twice as high for girls aged 15–19 than for women aged 20–24. The maternal mortality rate can be up to five times higher for girls aged 10–14 than for women aged 20–24. Illegal abortion also holds many risks for teenage girls in areas such as sub-Saharan Africa.

Risks for medical complications are greater for girls aged under 15, as an underdeveloped pelvis can lead to difficulties in childbirth. Obstructed labour is normally dealt with by caesarean section in industrialized nations; however, in developing regions where medical services might be unavailable, it can lead to eclampsia, obstetric fistula, infant mortality, or maternal death. For mothers who are older than fifteen, age in itself is not a risk factor, and poor outcomes are associated more with socioeconomic factors rather than with biology.

Economics

The lifetime opportunity cost caused by teenage pregnancy in different countries varies from 1% to 30% of the annual GDP (30% being the figure in Uganda). In the United States, teenage pregnancy costs taxpayers between $9.4 and $28 billion each year, due to factors such as foster care and lost tax revenue. The estimated increase in economic productivity from ending teenage pregnancy in Brazil and India would be over $3.5 billion and $7.7 billion respectively.

Less than one third of teenage mothers receive any form of child support, vastly increasing the likelihood of turning to the government for assistance. The correlation between earlier childbearing and failure to complete high school reduces career opportunities for many young women. One study found that, in 1988, 60% of teenage mothers were impoverished at the time of giving birth. Additional research found that nearly 50% of all adolescent mothers sought social assistance within the first five years of their child's life. A study of 100 teenaged mothers in the UK found that only 11% received a salary, while the remaining 89% were unemployed. Most British teenage mothers live in poverty, with nearly half in the bottom fifth of the income distribution.

Risk factors

Culture

Rates of teenage pregnancies are higher in societies where it is traditional for girls to marry young and where they are encouraged to bear children as soon as they are able. For example, in some sub-Saharan African countries, early pregnancy is often seen as a blessing because it is proof of the young woman's fertility. Countries where teenage marriages are common experience higher levels of teenage pregnancies. In the Indian subcontinent, early marriage and pregnancy is more common in traditional rural communities than in cities. Many teenagers are not taught about methods of birth control and how to deal with peers who pressure them into having sex before they are ready. Many pregnant teenagers do not have any cognition of the central facts of sexuality.

Economic incentives also influence the decision to have children. In societies where children are set to work at an early age, it is economically attractive to have many children.

In societies where adolescent marriage is less common, such as many developed countries, young age at first intercourse and lack of use of contraceptive methods (or their inconsistent and/or incorrect use; the use of a method with a high failure rate is also a problem) may be factors in teen pregnancy. Most teenage pregnancies in the developed world appear to be unplanned. Many Western countries have instituted sex education programs, the main objective of which is to reduce unplanned pregnancies and STIs. Countries with low levels of teenagers giving birth accept sexual relationships among teenagers and provide comprehensive and balanced information about sexuality.

Teenage pregnancies are common among Romani people because they marry earlier.

Other family members

Teen pregnancy and motherhood can influence younger siblings. One study found that the younger sisters of teen mothers were less likely to emphasize the importance of education and employment and more likely to accept human sexual behavior, parenting, and marriage at younger ages. Younger brothers, too, were found to be more tolerant of non-marital and early births, in addition to being more susceptible to high-risk behaviors. If the younger sisters of teenage parents babysit the children, they have an increased probability of getting pregnant themselves. Once an older daughter has a child, parents often become more accepting as time goes by. A study from Norway in 2011 found that the probability of a younger sister having a teenage pregnancy went from 1:5 to 2:5 if the elder sister had a baby as a teenager.

Sexuality

In most countries, most males experience sexual intercourse for the first time before their 20th birthday. Males in Western developed countries have sex for the first time sooner than in undeveloped and culturally conservative countries such as sub-Saharan Africa and much of Asia.

In a 2005 Kaiser Family Foundation study of US teenagers, 29% of teens reported feeling pressure to have sex, 33% of sexually active teens reported "being in a relationship where they felt things were moving too fast sexually", and 24% had "done something sexual they didn’t really want to do". Several polls have indicated peer pressure as a factor in encouraging both girls and boys to have sex. The increased sexual activity among adolescents is manifested in increased teenage pregnancies and an increase in sexually transmitted diseases.

Role of drug and alcohol use

Inhibition-reducing drugs and alcohol may possibly encourage unintended sexual activity. If so, it is unknown if the drugs themselves directly influence teenagers to engage in riskier behavior, or whether teenagers who engage in drug use are more likely to engage in sex. Correlation does not imply causation. The drugs with the strongest evidence linking them to teenage pregnancy are alcohol, cannabis, "ecstasy" and other substituted amphetamines. The drugs with the least evidence to support a link to early pregnancy are opioids, such as heroin, morphine, and oxycodone, of which a well-known effect is the significant reduction of libido – it appears that teenage opioid users have significantly reduced rates of conception compared to their non-using, and alcohol, "ecstasy", cannabis, and amphetamine using peers.

Early puberty

Girls who mature early (precocious puberty) are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse at a younger age, which in turn puts them at greater risk of teenage pregnancy.

Lack of contraception

Adolescents may lack knowledge of, or access to, conventional methods of preventing pregnancy, as they may be too embarrassed or frightened to seek such information. Contraception for teenagers presents a huge challenge for the clinician. In 1998, the government of the UK set a target to halve the under-18 pregnancy rate by 2010. The Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (TPS) was established to achieve this. The pregnancy rate in this group, although falling, rose slightly in 2007, to 41.7 per 1,000 women. Young women often think of contraception either as 'the pill' or condoms and have little knowledge about other methods. They are heavily influenced by negative, second-hand stories about methods of contraception from their friends and the media. Prejudices are extremely difficult to overcome. Over concern about side-effects, for example weight gain and acne, often affect choice. Missing up to three pills a month is common, and in this age group the figure is likely to be higher. Restarting after the pill-free week, having to hide pills, drug interactions and difficulty getting repeat prescriptions can all lead to method failure.

In the US, according to the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, sexually active adolescent women wishing to avoid pregnancy were less likely than older women to use contraceptives (18% of 15–19-year-olds used no contraceptives, versus 10.7% for women aged 15–44). More than 80% of teen pregnancies are unintended. Over half of unintended pregnancies were to women not using contraceptives, most of the rest are due to inconsistent or incorrect use. 23% of sexually active young women in a 1996 Seventeen magazine poll admitted to having had unprotected sex with a partner who did not use a condom, while 70% of girls in a 1997 PARADE poll claimed it was embarrassing to buy birth control or request information from a doctor.

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health surveyed 1027 students in the US in grades 7–12 in 1995 to compare the use of contraceptives among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. The results were that 36.2% of Hispanics said they never used contraception during intercourse which is a high rate compared to 23.3% of Black teens and 17.0% of White teens who also did not use contraceptives during intercourse

In a 2012 study, over 1,000 females were surveyed to find out factors contributing to not using contraception. Of those surveyed, almost half had been involved in unprotected sex within the previous three months. These women gave three main reasons for not using contraceptives: trouble obtaining birth control (the most frequent reason), lack of intention to have sex, and the misconception that they "could not get pregnant".

In a study for the Guttmacher Institute, researchers found that from a comparative perspective, however, teenage pregnancy rates in the US are less nuanced than one might initially assume. "Since timing and levels of sexual activity are quite similar across [Sweden, France, Canada, Great Britain, and the US], the high U.S. rates arise primarily because of less, and possibly less-effective, contraceptive use by sexually active teenagers." Thus, the cause for the discrepancy between rich nations can be traced largely to contraceptive-based issues.

Among teens in the UK seeking an abortion, a study found that the rate of contraceptive use was roughly the same for teens as for older women.

In other cases, contraception is used, but proves to be inadequate. Inexperienced adolescents may use condoms incorrectly, forget to take oral contraceptives, or fail to use the contraceptives they had previously chosen. Contraceptive failure rates are higher for teenagers, particularly poor ones, than for older users. Long-acting contraceptives such as intrauterine devices, subcutaneous contraceptive implants, and contraceptive injections (such as Depo-Provera and combined injectable contraceptive), which prevent pregnancy for months or years at a time, are more effective in women who have trouble remembering to take pills or using barrier methods consistently.

According to Encyclopedia of Women's Health, published in 2004, there has been an increased effort to provide contraception to adolescents via family planning services and school-based health, such as HIV prevention education.

Sexual abuse

Studies from South Africa have found that 11–20% of pregnancies in teenagers are a direct result of rape, while about 60% of teenage mothers had unwanted sexual experiences preceding their pregnancy. Before age 15, a majority of first-intercourse experiences among females are reported to be non-voluntary; the Guttmacher Institute found that 60% of girls who had sex before age 15 were coerced by males who on average were six years their senior. One in five teenage fathers admitted to forcing girls to have sex with them.

Multiple studies have indicated a strong link between early childhood sexual abuse and subsequent teenage pregnancy in industrialized countries. Up to 70% of women who gave birth in their teens were molested as young girls; by contrast, 25% of women who did not give birth as teens were molested.

In some countries, sexual intercourse between a minor and an adult is not considered consensual under the law because a minor is believed to lack the maturity and competence to make an informed decision to engage in fully consensual sex with an adult. In those countries, sex with a minor is therefore considered statutory rape. In most European countries, by contrast, once an adolescent has reached the age of consent, he or she can legally have sexual relations with adults because it is held that in general (although certain limitations may still apply), reaching the age of consent enables a juvenile to consent to sex with any partner who has also reached that age. Therefore, the definition of statutory rape is limited to sex with a person under the minimum age of consent. What constitutes statutory rape ultimately differs by jurisdiction.

Dating violence

Studies have indicated that adolescent girls are often in abusive relationships at the time of their conceiving. They have also reported that knowledge of their pregnancy has often intensified violent and controlling behaviors on part of their boyfriends. Girls under age 18 are twice as likely to be beaten by their child's father than women over age 18. A UK study found that 70% of women who gave birth in their teens had experienced adolescent domestic violence. Similar results have been found in studies in the US. A Washington State study found 70% of teenage mothers had been beaten by their boyfriends, 51% had experienced attempts of birth control sabotage within the last year, and 21% experienced school or work sabotage.

In a study of 379 pregnant or parenting teens and 95 teenage girls without children, 62% of girls aged 11–15 and 56% of girls aged 16–19 reported experiencing domestic violence at the hands of their partners. Moreover, 51% of the girls reported experiencing at least one instance where their boyfriend attempted to sabotage their efforts to use birth control.

Socioeconomic factors

Teenage pregnancy has been defined predominantly within the research field and among social agencies as a social problem. Poverty is associated with increased rates of teenage pregnancy. Economically poor countries such as Niger and Bangladesh have far more teenage mothers compared with economically rich countries such as Switzerland and Japan.

In the UK, around half of all pregnancies to under 18 are concentrated among the 30% most deprived population, with only 14% occurring among the 30% least deprived. For example, in Italy, the teenage birth rate in the well-off central regions is only 3.3 per 1,000, while in the poorer Mezzogiorno it is 10.0 per 1,000. Similarly, in the US, sociologist Mike A. Males noted that teenage birth rates closely mapped poverty rates in California:

| County | Poverty rate | Birth rate* |

|---|---|---|

| Marin County | 5% | 5 |

| Tulare County (Caucasians) | 18% | 50 |

| Tulare County (Hispanics) | 40% | 100 |

* per 1,000 women aged 15–19

Teen pregnancy cost the US over $9.1 billion in 2004, including $1.9 billion for health care, $2.3 billion for child welfare, $2.1 billion for incarceration, and $2.9 billion in lower tax revenue.

There is little evidence to support the common belief that teenage mothers become pregnant to get benefits, welfare, and council housing. Most knew little about housing or financial aid before they got pregnant and what they thought they knew often turned out to be wrong.

Childhood environment

Girls exposed to abuse, domestic violence, and family strife in childhood are more likely to become pregnant as teenagers, and the risk of becoming pregnant as a teenager increases with the number of adverse childhood experiences. According to a 2004 study, one-third of teenage pregnancies could be prevented by eliminating exposure to abuse, violence, and family strife. The researchers note that "family dysfunction has enduring and unfavorable health consequences for women during the adolescent years, the childbearing years, and beyond." When the family environment does not include adverse childhood experiences, becoming pregnant as an adolescent does not appear to raise the likelihood of long-term, negative psychosocial consequences. Studies have also found that boys raised in homes with a battered mother, or who experienced physical violence directly, were significantly more likely to impregnate a girl.

Studies have also found that girls whose fathers left the family early in their lives had the highest rates of early sexual activity and adolescent pregnancy. Girls whose fathers left them at a later age had a lower rate of early sexual activity, and the lowest rates are found in girls whose fathers were present throughout their childhood. Even when the researchers took into account other factors that could have contributed to early sexual activity and pregnancy, such as behavioral problems and life adversity, early father-absent girls were still about five times more likely in the US and three times more likely in New Zealand to become pregnant as adolescents than were father-present girls.

Low educational expectations have been pinpointed as a risk factor. A girl is also more likely to become a teenage parent if her mother or older sister gave birth in her teens. A majority of respondents in a 1988 Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies survey attributed the occurrence of adolescent pregnancy to a breakdown of communication between parents and child and also to inadequate parental supervision.

Foster care youth are more likely than their peers to become pregnant as teenagers. The National Casey Alumni Study, which surveyed foster care alumni from 23 communities across the US, found the birth rate for girls in foster care was more than double the rate of their peers outside the foster care system. A University of Chicago study of youth transitioning out of foster care in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin found that nearly half of the females had been pregnant by age 19. The Utah Department of Human Services found that girls who had left the foster care system between 1999 and 2004 had a birth rate nearly three times the rate for girls in the general population.

Media influence

A study conducted in 2006 found that, adolescents who were more exposed to sexuality in the media were also more likely to engage in sexual activity themselves. According to Time, "teens exposed to the most sexual content on TV are twice as likely as teens watching less of this material to become pregnant before they reach age 20".

Prevention

Comprehensive sex education and access to birth control appear to reduce unplanned teenage pregnancy. It is unclear which type of intervention is most effective.

In the US free access to a long acting form of reversible birth control along with education decreased the rates of teen pregnancies by around 80% and the rate of abortions by more than 75%. Currently there are four federal programs aimed at preventing teenage pregnancy: Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP), Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), Title V Sexual Risk Avoidance Education, and Sexual Risk Avoidance Education.

Education

The Dutch approach to preventing teenage pregnancy has often been seen as a model by other countries. The curriculum focuses on values, attitudes, communication and negotiation skills, as well as biological aspects of reproduction. The media has encouraged open dialogue and the health-care system guarantees confidentiality and a non-judgmental approach.

In the United States, only 39 states and the District of Columbia out of the 50 states require some form of sex education of HIV education. Out of these 39 states and the District of Columbia, only 17 states require that the sexual education provided be medically accurate, and only 3 states prohibit a program from promoting sexual education in a religious way. These three states include California, Colorado, and Louisiana. Additionally, 19 of those 39 states stress the importance of only having sex when in a committed marriage. From this data, 11 states currently have no requirement for sexual education for any years of schooling, meaning these 11 states may have no sexual education at all. This could also mean these states are allowed to teach sexual education in anyway they would like, including in medically inaccurate ways. This point is also valid for those 22 states that do not require sexual education to be medically accurate. Comprehensive sexual education has been proven to work to reduce the risk of teen pregnancies. Without a nation wide mandate for medically accurate programs, teenagers in the United States are at risk for missing out on valuable information that can protect them. It is unfair to expect teenagers to make educated decisions about sex that can lead to teen pregnancy when they have never been properly educated about the issue. A program developed by experts in public health and sexual education titled National Sexuality Education Standards, is a valuable resource that describes what the minimum requirements of sexual education should be across the nation. Giving teenagers the tools that are outlined in that roadmap would have positive effects, as it gives teenagers the resources to make educated decisions. Currently, there is not a national implementation of this program in the United States.

Abstinence only education

Some schools provide abstinence-only sex education. Evidence does not support the effectiveness of abstinence-only sex education. It has been found to be ineffective in decreasing HIV risk in the developed world, and does not decrease rates of unplanned pregnancy when compared to comprehensive sex education. It does not decrease the sexual activity rates of students, when compared to students who undertake comprehensive sexual education classes.

Public policy

Canada

In 2018, Québec's Institut national de santé publique (INSPQ) began implementing adjustments to the Protocole de contraception du Québec (Québec Contraception Protocol). The new protocol allows registered nurses to prescribe hormonal birth control, an IUD or emergency birth control to women, as long as they comply with prescribed standards in the Prescription infirmière : Guide explicatif conjoint, and are properly trained in providing contraceptives. In 2020, Québec will offer online training to registered nurses, provided by the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec (OIIQ). Nurses that do not have training in the areas of sexually transmitted and blood borne infections may have to take additional online courses provided by the INSPQ.

United States

In the US, one policy initiative that has been used to increase rates of contraceptive use is Title X. Title X of the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970 (Pub.L. 91–572) provides family planning services for those who do not qualify for Medicaid by distributing "funding to a network of public, private, and nonprofit entities [to provide] services on a sliding scale based on income." Studies indicate that, internationally, success in reducing teen pregnancy rates is directly correlated with the kind of access that Title X provides: “What appears crucial to success is that adolescents know where they can go to obtain information and services, can get there easily and are assured of receiving confidential, nonjudgmental care, and that these services and contraceptive supplies are free or cost very little.” In addressing high rates of unplanned teen pregnancies, scholars agree that the problem must be confronted from both the biological and cultural contexts.

On September 30, 2010, the US Department of Health and Human Services approved $155 million in new funding for comprehensive sex education programs designed to prevent teenage pregnancy. The money is being awarded "to states, non-profit organizations, school districts, universities and others. These grants will support the replication of teen pregnancy prevention programs that have been shown to be effective through rigorous research as well as the testing of new, innovative approaches to combating teen pregnancy." Of the total of $150 million, $55 million is funded by Affordable Care Act through the Personal Responsibility Education Program, which requires states receiving funding to incorporate lessons about both abstinence and contraception.

Developing countries

In the developing world, programs of reproductive health aimed at teenagers are often small scale and not centrally coordinated, although some countries such as Sri Lanka have a systematic policy framework for teaching about sex within schools. Non-governmental agencies such as the International Planned Parenthood Federation and Marie Stopes International provide contraceptive advice for young women worldwide. Laws against child marriage have reduced but not eliminated the practice. Improved female literacy and educational prospects have led to an increase in the age at first birth in areas such as Iran, Indonesia, and the Indian state of Kerala.

Other

A team of researchers and educators in California have published a list of "best practices" in the prevention of teen pregnancy, which includes, in addition to the previously mentioned concepts, working to "instill a belief in a successful future", male involvement in the prevention process, and designing interventions that are culturally relevant.

Prevalence

In reporting teenage pregnancy rates, the number of pregnancies per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 when the pregnancy ends is generally used.

Worldwide, teenage pregnancy rates range from 143 per 1,000 in some sub-Saharan African countries to 2.9 per 1,000 in South Korea. In the US, 82% of pregnancies in those between 15 and 19 are unplanned. Among OECD developed countries, the US, the UK and New Zealand have the highest level of teenage pregnancy, while Japan and South Korea have the lowest in 2001. According to the UNFPA, “In every region of the world – including high-income countries – girls who are poor, poorly educated or living in rural areas are at greater risk of becoming pregnant than those who are wealthier, well-educated or urban. This is true on a global level, as well: 95 per cent of the world’s births to adolescents (aged 15–19) take place in developing countries. Every year, some 3 million girls in this age bracket resort to unsafe abortions, risking their lives and health.”

According to a 2001 UNICEF survey, in 10 out of 12 developed nations with available data, more than two thirds of young people have had sexual intercourse while still in their teens. In Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, the UK and the US, the proportion is over 80%. In Australia, the UK and the US, approximately 25% of 15-year-olds and 50% of 17-year-olds have had sex. According to the Encyclopedia of Women's Health, published in 2004, approximately 15 million girls under the age of 20 in the world have a child each year. Estimates were that 20–60% of these pregnancies in developing countries are mistimed or unwanted.

Save the Children found that, annually, 13 million children are born to women aged under 20 worldwide, more than 90% in developing countries. Complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of mortality among women aged 15–19 in such areas.

Sub-Saharan Africa

The highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the world is in sub-Saharan Africa, where women tend to marry at an early age. In Niger, for example, 87% of women surveyed were married and 53% had given birth to a child before the age of 18. A recent study found that socio-cultural factors, economic factors, environmental factors, individual factors, and health service-related factors were responsible for the high rates of teenage pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa.

India

In the Indian subcontinent, early marriage sometimes results in adolescent pregnancy, particularly in rural regions where the rate is much higher than it is in urbanized areas. Latest data suggests that teen pregnancy in India is high with 62 pregnant teens out of every 1,000 women. India is fast approaching to be the most populous country in the world by 2050 and increasing teenage pregnancy, an important factor for the population rise, is likely to aggravate the problems.

Asia

The rates of early marriage and pregnancy in some Asian countries are high. In recent years, the rates have decreased sharply in Indonesia and Malaysia, although it remains relatively high in the former. However, in the industrialized Asian nations such as South Korea and Singapore, teenage birth rates remain among the lowest in the world.

Australia

In 2015, the birth rate among teenage women in Australia was 11.9 births per 1,000 women. The rate has fallen from 55.5 births per 1,000 women in 1971, probably due to ease of access to effective birth control, rather than any decrease in sexual activity.

Europe

The overall trend in Europe since 1970 has been a decreasing total fertility rate, an increase in the age at which women experience their first birth, and a decrease in the number of births among teenagers. Most continental Western European countries have very low teenage birth rates. This is varyingly attributed to good sex education and high levels of contraceptive use (in the case of the Netherlands and Scandinavia), traditional values and social stigmatization (in the case of Spain and Italy) or both (in the case of Switzerland).

On the other hand, the teen birth rate is very high in Bulgaria and Romania. As of 2015, Bulgaria had a birth rate of 37/1.000 women aged 15–19, and Romania of 34. The teen birth rate of these two countries is even higher than that of underdeveloped countries like Burundi and Rwanda. Many of the teen births occur in Roma populations, who have an occurrence of teenage pregnancies well above the local average.

United Kingdom

The teen pregnancy rate in England and Wales was 23.3 per 1,000 women aged 15 to 17. There were 5,740 pregnancies in girls aged under 18 in the three months to June 2014, data from the Office for National Statistics shows. This compares with 6,279 in the same period in 2013 and 7,083 for the June quarter the year before that. Historically, the UK has had one of the highest teenage pregnancy and abortion rates in Western Europe.

There are no comparable rates for conceptions across Europe, but the under-18 birth rate suggests England is closing the gap. The under-18 birth rate in 2012 in England and Wales was 9.2, compared with an EU average of 6.9. However, the UK birth rate has fallen by almost a third (32.3%) since 2004 compared with a fall of 15.6% in the EU. In 2004, the UK rate was 13.6 births per 1,000 women aged 15–17 compared with an EU average rate of 7.7.

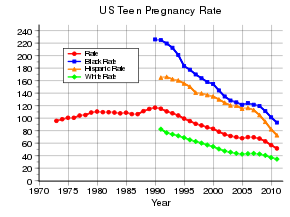

United States

In 2001, the teenage birth rate in the US was the highest in the developed world, and the teenage abortion rate is also high. In 2005 in the US, the majority (57%) of teen pregnancies resulted in a live birth, 27% ended in an induced abortion, and 16% in a fetal loss. The US teenage pregnancy rate was at a high in the 1950s and has decreased since then, although there has been an increase in births out of wedlock. The teenage pregnancy rate decreased significantly in the 1990s; this decline manifested across all racial groups, although teenagers of African-American and Hispanic descent retain a higher rate, in comparison to that of European-Americans and Asian-Americans. The Guttmacher Institute attributed about 25% of the decline to abstinence and 75% to the effective use of contraceptives. While in 2006 the US teen birth rate rose for the first time in fourteen years, it reached a historic low in 2010: 34.3 births per 1,000 women aged 15–19. As of 2017, the birth rate for teen pregnancy from girls ages 15-19 was at 18.8 per 1,000 women between this age group.

The Latina teenage pregnancy rate is 75% higher pregnancy rate than the national average.

The latest data from the US shows that the states with the highest teenage birthrate are Mississippi, New Mexico and Arkansas while the states with the lowest teenage birthrate are New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont.

Canada

The Canadian teenage birth trended towards a steady decline for both younger (15–17) and older (18–19) teens in the period between 1992 and 2002; however, teen pregnancy has been on the rise since 2013.

Teenage fatherhood

In some cases, the father of the child is the husband of the teenage girl. The conception may occur within wedlock, or the pregnancy itself may precipitate the marriage (the so-called shotgun wedding). In countries such as India, the majority of teenage births occur within marriage.

In other countries, such as the US and Ireland, the majority of teenage mothers are not married to the father of their children. In the UK, half of all teenagers with children are lone parents, 40% are cohabitating as a couple and 10% are married. Teenage parents are frequently in a romantic relationship at the time of birth, but many adolescent fathers do not stay with the mother and this often disrupts their relationship with the child. US surveys tend to under-report the prevalence of teen fatherhood. In many cases, "teenage father" may be a misnomer. Studies by the Population Reference Bureau and the National Center for Health Statistics found that about two-thirds of births to teenage girls in the US are fathered by adult men aged over 20. The Guttmacher Institute reports that over 40% of mothers aged 15–17 had sexual partners three to five years older and almost one in five had partners six or more years older. A 1990 study of births to California teens reported that the younger the mother, the greater the age gap with her male partner. In the UK, 72% of jointly registered births to women aged under 20, the father is over 20, with almost 1 in 4 being over 25.

Society and culture

Politics

Some politicians condemn pregnancy in unmarried teenagers as a drain on taxpayers, if the mothers and children receive welfare payments and social housing from the government.