Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, Ocham's razor (Latin: novacula Occami), or the principle of parsimony or law of parsimony (Latin: lex parsimoniae) is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity", sometimes inaccurately paraphrased as "the simplest explanation is usually the best one." The idea is attributed to English Franciscan friar William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347), a scholastic philosopher and theologian who used a preference for simplicity to defend the idea of divine miracles. This philosophical razor advocates that when presented with competing hypotheses about the same prediction, one should select the solution with the fewest assumptions, and that this is not meant to be a way of choosing between hypotheses that make different predictions.

Similarly, in science, Occam's razor is used as an abductive heuristic in the development of theoretical models rather than as a rigorous arbiter between candidate models. In the scientific method, Occam's razor is not considered an irrefutable principle of logic or a scientific result; the preference for simplicity in the scientific method is based on the falsifiability criterion. For each accepted explanation of a phenomenon, there may be an extremely large, perhaps even incomprehensible, number of possible and more complex alternatives. Since failing explanations can always be burdened with ad hoc hypotheses to prevent them from being falsified, simpler theories are preferable to more complex ones because they tend to be more testable.

History

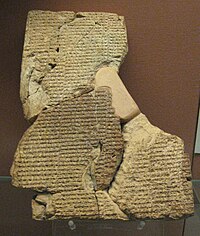

The phrase Occam's razor did not appear until a few centuries after William of Ockham's death in 1347. Libert Froidmont, in his On Christian Philosophy of the Soul, takes credit for the phrase, speaking of "novacula occami". Ockham did not invent this principle, but the "razor"—and its association with him—may be due to the frequency and effectiveness with which he used it. Ockham stated the principle in various ways, but the most popular version, "Entities are not to be multiplied without necessity" (Non sunt multiplicanda entia sine necessitate) was formulated by the Irish Franciscan philosopher John Punch in his 1639 commentary on the works of Duns Scotus.

Formulations before William of Ockham

The origins of what has come to be known as Occam's razor are traceable to the works of earlier philosophers such as John Duns Scotus (1265–1308), Robert Grosseteste (1175–1253), Maimonides (Moses ben-Maimon, 1138–1204), and even Aristotle (384–322 BC). Aristotle writes in his Posterior Analytics, "We may assume the superiority ceteris paribus [other things being equal] of the demonstration which derives from fewer postulates or hypotheses." Ptolemy (c. AD 90 – c. AD 168) stated, "We consider it a good principle to explain the phenomena by the simplest hypothesis possible."

Phrases such as "It is vain to do with more what can be done with fewer" and "A plurality is not to be posited without necessity" were commonplace in 13th-century scholastic writing. Robert Grosseteste, in Commentary on [Aristotle's] the Posterior Analytics Books (Commentarius in Posteriorum Analyticorum Libros) (c. 1217–1220), declares: "That is better and more valuable which requires fewer, other circumstances being equal... For if one thing were demonstrated from many and another thing from fewer equally known premises, clearly that is better which is from fewer because it makes us know quickly, just as a universal demonstration is better than particular because it produces knowledge from fewer premises. Similarly in natural science, in moral science, and in metaphysics the best is that which needs no premises and the better that which needs the fewer, other circumstances being equal."

The Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) states that "it is superfluous to suppose that what can be accounted for by a few principles has been produced by many." Aquinas uses this principle to construct an objection to God's existence, an objection that he in turn answers and refutes generally (cf. quinque viae), and specifically, through an argument based on causality. Hence, Aquinas acknowledges the principle that today is known as Occam's razor, but prefers causal explanations to other simple explanations.

William of Ockham

William of Ockham (circa 1287–1347) was an English Franciscan friar and theologian, an influential medieval philosopher and a nominalist. His popular fame as a great logician rests chiefly on the maxim attributed to him and known as Occam's razor. The term razor refers to distinguishing between two hypotheses either by "shaving away" unnecessary assumptions or cutting apart two similar conclusions.

While it has been claimed that Occam's razor is not found in any of William's writings, one can cite statements such as Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate William of Ockham – Wikiquote ("Plurality must never be posited without necessity"), which occurs in his theological work on the Sentences of Peter Lombard (Quaestiones et decisiones in quattuor libros Sententiarum Petri Lombardi; ed. Lugd., 1495, i, dist. 27, qu. 2, K).

Nevertheless, the precise words sometimes attributed to William of Ockham, Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem (Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity), are absent in his extant works; this particular phrasing comes from John Punch, who described the principle as a "common axiom" (axioma vulgare) of the Scholastics. William of Ockham's contribution seems to restrict the operation of this principle in matters pertaining to miracles and God's power; so, in the Eucharist, a plurality of miracles is possible, simply because it pleases God.

This principle is sometimes phrased as Pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate ("Plurality should not be posited without necessity"). In his Summa Totius Logicae, i. 12, William of Ockham cites the principle of economy, Frustra fit per plura quod potest fieri per pauciora ("It is futile to do with more things that which can be done with fewer"; Thorburn, 1918, pp. 352–53; Kneale and Kneale, 1962, p. 243.)

Later formulations

To quote Isaac Newton, "We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances. Therefore, to the same natural effects we must, as far as possible, assign the same causes." In the sentence hypotheses non fingo, Newton affirms the success of this approach.

Bertrand Russell offers a particular version of Occam's razor: "Whenever possible, substitute constructions out of known entities for inferences to unknown entities."

Around 1960, Ray Solomonoff founded the theory of universal inductive inference, the theory of prediction based on observations – for example, predicting the next symbol based upon a given series of symbols. The only assumption is that the environment follows some unknown but computable probability distribution. This theory is a mathematical formalization of Occam's razor.

Another technical approach to Occam's razor is ontological parsimony. Parsimony means spareness and is also referred to as the Rule of Simplicity. This is considered a strong version of Occam's razor. A variation used in medicine is called the "Zebra": a physician should reject an exotic medical diagnosis when a more commonplace explanation is more likely, derived from Theodore Woodward's dictum "When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses not zebras".

Ernst Mach formulated the stronger version of Occam's razor into physics, which he called the Principle of Economy stating: "Scientists must use the simplest means of arriving at their results and exclude everything not perceived by the senses."

This principle goes back at least as far as Aristotle, who wrote "Nature operates in the shortest way possible." The idea of parsimony or simplicity in deciding between theories, though not the intent of the original expression of Occam's razor, has been assimilated into common culture as the widespread layman's formulation that "the simplest explanation is usually the correct one."

Justifications

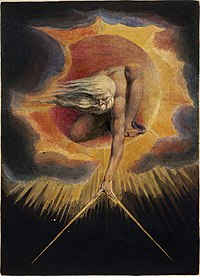

Aesthetic

Prior to the 20th century, it was a commonly held belief that nature itself was simple and that simpler hypotheses about nature were thus more likely to be true. This notion was deeply rooted in the aesthetic value that simplicity holds for human thought, and the justifications presented for it often drew from theology. Thomas Aquinas made this argument in the 13th century, writing, "If a thing can be done adequately by means of one, it is superfluous to do it by means of several; for we observe that nature does not employ two instruments [if] one suffices."

Beginning in the 20th century, epistemological justifications based on induction, logic, pragmatism, and especially probability theory have become more popular among philosophers.

Empirical

Occam's razor has gained strong empirical support in helping to converge on better theories (see "Applications" section below for some examples).

In the related concept of overfitting, excessively complex models are affected by statistical noise (a problem also known as the bias-variance trade-off), whereas simpler models may capture the underlying structure better and may thus have better predictive performance. It is, however, often difficult to deduce which part of the data is noise (cf. model selection, test set, minimum description length, Bayesian inference, etc.).

Testing the razor

The razor's statement that "other things being equal, simpler explanations are generally better than more complex ones" is amenable to empirical testing. Another interpretation of the razor's statement would be that "simpler hypotheses are generally better than the complex ones". The procedure to test the former interpretation would compare the track records of simple and comparatively complex explanations. If one accepts the first interpretation, the validity of Occam's razor as a tool would then have to be rejected if the more complex explanations were more often correct than the less complex ones (while the converse would lend support to its use). If the latter interpretation is accepted, the validity of Occam's razor as a tool could possibly be accepted if the simpler hypotheses led to correct conclusions more often than not.

Even if some increases in complexity are sometimes necessary, there still remains a justified general bias toward the simpler of two competing explanations. To understand why, consider that for each accepted explanation of a phenomenon, there is always an infinite number of possible, more complex, and ultimately incorrect, alternatives. This is so because one can always burden a failing explanation with an ad hoc hypothesis. Ad hoc hypotheses are justifications that prevent theories from being falsified.

For example, if an individual makes supernatural claims that leprechauns were responsible for breaking a vase, a simpler explanation might be that he did it, but ongoing ad hoc justifications (e.g. "... and that's not me breaking it on the film; they tampered with that, too") could successfully prevent complete disproof. This endless supply of elaborate competing explanations, called saving hypotheses, cannot be technically ruled out – except by using Occam's razor.

Of course any more complex theory might still possibly be true. A study of the predictive validity of Occam's razor found 32 published papers that included 97 comparisons of economic forecasts from simple and complex forecasting methods. None of the papers provided a balance of evidence that complexity of method improved forecast accuracy. In the 25 papers with quantitative comparisons, complexity increased forecast errors by an average of 27 percent.

Practical considerations and pragmatism

Mathematical

One justification of Occam's razor is a direct result of basic probability theory. By definition, all assumptions introduce possibilities for error; if an assumption does not improve the accuracy of a theory, its only effect is to increase the probability that the overall theory is wrong.

There have also been other attempts to derive Occam's razor from probability theory, including notable attempts made by Harold Jeffreys and E. T. Jaynes. The probabilistic (Bayesian) basis for Occam's razor is elaborated by David J. C. MacKay in chapter 28 of his book Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms, where he emphasizes that a prior bias in favor of simpler models is not required.

William H. Jefferys and James O. Berger (1991) generalize and quantify the original formulation's "assumptions" concept as the degree to which a proposition is unnecessarily accommodating to possible observable data. They state, "A hypothesis with fewer adjustable parameters will automatically have an enhanced posterior probability, due to the fact that the predictions it makes are sharp." The use of "sharp" here is not only a tongue-in-cheek reference to the idea of a razor, but also indicates that such predictions are more accurate than competing predictions. The model they propose balances the precision of a theory's predictions against their sharpness, preferring theories that sharply make correct predictions over theories that accommodate a wide range of other possible results. This, again, reflects the mathematical relationship between key concepts in Bayesian inference (namely marginal probability, conditional probability, and posterior probability).

The bias–variance tradeoff is a framework that incorporates the Occam's razor principle in its balance between overfitting (associated with lower bias but higher variance) and underfitting (associated with lower variance but higher bias).

Other philosophers

Karl Popper

Karl Popper argues that a preference for simple theories need not appeal to practical or aesthetic considerations. Our preference for simplicity may be justified by its falsifiability criterion: we prefer simpler theories to more complex ones "because their empirical content is greater; and because they are better testable". The idea here is that a simple theory applies to more cases than a more complex one, and is thus more easily falsifiable. This is again comparing a simple theory to a more complex theory where both explain the data equally well.

Elliott Sober

The philosopher of science Elliott Sober once argued along the same lines as Popper, tying simplicity with "informativeness": The simplest theory is the more informative, in the sense that it requires less information to a question. He has since rejected this account of simplicity, purportedly because it fails to provide an epistemic justification for simplicity. He now believes that simplicity considerations (and considerations of parsimony in particular) do not count unless they reflect something more fundamental. Philosophers, he suggests, may have made the error of hypostatizing simplicity (i.e., endowed it with a sui generis existence), when it has meaning only when embedded in a specific context (Sober 1992). If we fail to justify simplicity considerations on the basis of the context in which we use them, we may have no non-circular justification: "Just as the question 'why be rational?' may have no non-circular answer, the same may be true of the question 'why should simplicity be considered in evaluating the plausibility of hypotheses?'"

Richard Swinburne

Richard Swinburne argues for simplicity on logical grounds:

... the simplest hypothesis proposed as an explanation of phenomena is more likely to be the true one than is any other available hypothesis, that its predictions are more likely to be true than those of any other available hypothesis, and that it is an ultimate a priori epistemic principle that simplicity is evidence for truth.

— Swinburne 1997

According to Swinburne, since our choice of theory cannot be determined by data (see Underdetermination and Duhem–Quine thesis), we must rely on some criterion to determine which theory to use. Since it is absurd to have no logical method for settling on one hypothesis amongst an infinite number of equally data-compliant hypotheses, we should choose the simplest theory: "Either science is irrational [in the way it judges theories and predictions probable] or the principle of simplicity is a fundamental synthetic a priori truth.".

Ludwig Wittgenstein

From the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

- 3.328 "If a sign is not necessary then it is meaningless. That is the meaning of Occam's Razor."

- (If everything in the symbolism works as though a sign had meaning, then it has meaning.)

- 4.04 "In the proposition there must be exactly as many things distinguishable as there are in the state of affairs, which it represents. They must both possess the same logical (mathematical) multiplicity (cf. Hertz's Mechanics, on Dynamic Models)."

- 5.47321 "Occam's Razor is, of course, not an arbitrary rule nor one justified by its practical success. It simply says that unnecessary elements in a symbolism mean nothing. Signs which serve one purpose are logically equivalent; signs which serve no purpose are logically meaningless."

and on the related concept of "simplicity":

- 6.363 "The procedure of induction consists in accepting as true the simplest law that can be reconciled with our experiences."

Uses

Science and the scientific method

In science, Occam's razor is used as a heuristic to guide scientists in developing theoretical models rather than as an arbiter between published models. In physics, parsimony was an important heuristic in Albert Einstein's formulation of special relativity, in the development and application of the principle of least action by Pierre Louis Maupertuis and Leonhard Euler, and in the development of quantum mechanics by Max Planck, Werner Heisenberg and Louis de Broglie.

In chemistry, Occam's razor is often an important heuristic when developing a model of a reaction mechanism. Although it is useful as a heuristic in developing models of reaction mechanisms, it has been shown to fail as a criterion for selecting among some selected published models. In this context, Einstein himself expressed caution when he formulated Einstein's Constraint: "It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience". An often-quoted version of this constraint (which cannot be verified as posited by Einstein himself) says "Everything should be kept as simple as possible, but not simpler."

In the scientific method, parsimony is an epistemological, metaphysical or heuristic preference, not an irrefutable principle of logic or a scientific result. As a logical principle, Occam's razor would demand that scientists accept the simplest possible theoretical explanation for existing data. However, science has shown repeatedly that future data often support more complex theories than do existing data. Science prefers the simplest explanation that is consistent with the data available at a given time, but the simplest explanation may be ruled out as new data become available. That is, science is open to the possibility that future experiments might support more complex theories than demanded by current data and is more interested in designing experiments to discriminate between competing theories than favoring one theory over another based merely on philosophical principles.

When scientists use the idea of parsimony, it has meaning only in a very specific context of inquiry. Several background assumptions are required for parsimony to connect with plausibility in a particular research problem. The reasonableness of parsimony in one research context may have nothing to do with its reasonableness in another. It is a mistake to think that there is a single global principle that spans diverse subject matter.

It has been suggested that Occam's razor is a widely accepted example of extraevidential consideration, even though it is entirely a metaphysical assumption. There is little empirical evidence that the world is actually simple or that simple accounts are more likely to be true than complex ones.

Most of the time, Occam's razor is a conservative tool, cutting out "crazy, complicated constructions" and assuring "that hypotheses are grounded in the science of the day", thus yielding "normal" science: models of explanation and prediction. There are, however, notable exceptions where Occam's razor turns a conservative scientist into a reluctant revolutionary. For example, Max Planck interpolated between the Wien and Jeans radiation laws and used Occam's razor logic to formulate the quantum hypothesis, even resisting that hypothesis as it became more obvious that it was correct.

Appeals to simplicity were used to argue against the phenomena of meteorites, ball lightning, continental drift, and reverse transcriptase. One can argue for atomic building blocks for matter, because it provides a simpler explanation for the observed reversibility of both mixing and chemical reactions as simple separation and rearrangements of atomic building blocks. At the time, however, the atomic theory was considered more complex because it implied the existence of invisible particles that had not been directly detected. Ernst Mach and the logical positivists rejected John Dalton's atomic theory until the reality of atoms was more evident in Brownian motion, as shown by Albert Einstein.

In the same way, postulating the aether is more complex than transmission of light through a vacuum. At the time, however, all known waves propagated through a physical medium, and it seemed simpler to postulate the existence of a medium than to theorize about wave propagation without a medium. Likewise, Newton's idea of light particles seemed simpler than Christiaan Huygens's idea of waves, so many favored it. In this case, as it turned out, neither the wave—nor the particle—explanation alone suffices, as light behaves like waves and like particles.

Three axioms presupposed by the scientific method are realism (the existence of objective reality), the existence of natural laws, and the constancy of natural law. Rather than depend on provability of these axioms, science depends on the fact that they have not been objectively falsified. Occam's razor and parsimony support, but do not prove, these axioms of science. The general principle of science is that theories (or models) of natural law must be consistent with repeatable experimental observations. This ultimate arbiter (selection criterion) rests upon the axioms mentioned above.

If multiple models of natural law make exactly the same testable predictions, they are equivalent and there is no need for parsimony to choose a preferred one. For example, Newtonian, Hamiltonian and Lagrangian classical mechanics are equivalent. Physicists have no interest in using Occam's razor to say the other two are wrong. Likewise, there is no demand for simplicity principles to arbitrate between wave and matrix formulations of quantum mechanics. Science often does not demand arbitration or selection criteria between models that make the same testable predictions.

Biology

Biologists or philosophers of biology use Occam's razor in either of two contexts both in evolutionary biology: the units of selection controversy and systematics. George C. Williams in his book Adaptation and Natural Selection (1966) argues that the best way to explain altruism among animals is based on low-level (i.e., individual) selection as opposed to high-level group selection. Altruism is defined by some evolutionary biologists (e.g., R. Alexander, 1987; W. D. Hamilton, 1964) as behavior that is beneficial to others (or to the group) at a cost to the individual, and many posit individual selection as the mechanism that explains altruism solely in terms of the behaviors of individual organisms acting in their own self-interest (or in the interest of their genes, via kin selection). Williams was arguing against the perspective of others who propose selection at the level of the group as an evolutionary mechanism that selects for altruistic traits (e.g., D. S. Wilson & E. O. Wilson, 2007). The basis for Williams' contention is that of the two, individual selection is the more parsimonious theory. In doing so he is invoking a variant of Occam's razor known as Morgan's Canon: "In no case is an animal activity to be interpreted in terms of higher psychological processes, if it can be fairly interpreted in terms of processes which stand lower in the scale of psychological evolution and development." (Morgan 1903).

However, more recent biological analyses, such as Richard Dawkins' The Selfish Gene, have contended that Morgan's Canon is not the simplest and most basic explanation. Dawkins argues the way evolution works is that the genes propagated in most copies end up determining the development of that particular species, i.e., natural selection turns out to select specific genes, and this is really the fundamental underlying principle that automatically gives individual and group selection as emergent features of evolution.

Zoology provides an example. Muskoxen, when threatened by wolves, form a circle with the males on the outside and the females and young on the inside. This is an example of a behavior by the males that seems to be altruistic. The behavior is disadvantageous to them individually but beneficial to the group as a whole and was thus seen by some to support the group selection theory. Another interpretation is kin selection: if the males are protecting their offspring, they are protecting copies of their own alleles. Engaging in this behavior would be favored by individual selection if the cost to the male musk ox is less than half of the benefit received by his calf – which could easily be the case if wolves have an easier time killing calves than adult males. It could also be the case that male musk oxen would be individually less likely to be killed by wolves if they stood in a circle with their horns pointing out, regardless of whether they were protecting the females and offspring. That would be an example of regular natural selection – a phenomenon called "the selfish herd".

Systematics is the branch of biology that attempts to establish patterns of relationship among biological taxa, today generally thought to reflect evolutionary history. It is also concerned with their classification. There are three primary camps in systematics: cladists, pheneticists, and evolutionary taxonomists. Cladists hold that classification should be based on synapomorphies (shared, derived character states), pheneticists contend that overall similarity (synapomorphies and complementary symplesiomorphies) is the determining criterion, while evolutionary taxonomists say that both genealogy and similarity count in classification (in a manner determined by the evolutionary taxonomist).

It is among the cladists that Occam's razor is applied, through the method of cladistic parsimony. Cladistic parsimony (or maximum parsimony) is a method of phylogenetic inference that yields phylogenetic trees (more specifically, cladograms). Cladograms are branching, diagrams used to represent hypotheses of relative degree of relationship, based on synapomorphies. Cladistic parsimony is used to select as the preferred hypothesis of relationships the cladogram that requires the fewest implied character state transformations (or smallest weight, if characters are differentially weighted). Critics of the cladistic approach often observe that for some types of data, parsimony could produce the wrong results, regardless of how much data is collected (this is called statistical inconsistency, or long branch attraction). However, this criticism is also potentially true for any type of phylogenetic inference, unless the model used to estimate the tree reflects the way that evolution actually happened. Because this information is not empirically accessible, the criticism of statistical inconsistency against parsimony holds no force. For a book-length treatment of cladistic parsimony, see Elliott Sober's Reconstructing the Past: Parsimony, Evolution, and Inference (1988). For a discussion of both uses of Occam's razor in biology, see Sober's article "Let's Razor Ockham's Razor" (1990).

Other methods for inferring evolutionary relationships use parsimony in a more general way. Likelihood methods for phylogeny use parsimony as they do for all likelihood tests, with hypotheses requiring fewer differing parameters (i.e., numbers or different rates of character change or different frequencies of character state transitions) being treated as null hypotheses relative to hypotheses requiring more differing parameters. Thus, complex hypotheses must predict data much better than do simple hypotheses before researchers reject the simple hypotheses. Recent advances employ information theory, a close cousin of likelihood, which uses Occam's razor in the same way. Of course, the choice of the "shortest tree" relative to a not-so-short tree under any optimality criterion (smallest distance, fewest steps, or maximum likelihood) is always based on parsimony.

Francis Crick has commented on potential limitations of Occam's razor in biology. He advances the argument that because biological systems are the products of (an ongoing) natural selection, the mechanisms are not necessarily optimal in an obvious sense. He cautions: "While Ockham's razor is a useful tool in the physical sciences, it can be a very dangerous implement in biology. It is thus very rash to use simplicity and elegance as a guide in biological research." This is an ontological critique of parsimony.

In biogeography, parsimony is used to infer ancient vicariant events or migrations of species or populations by observing the geographic distribution and relationships of existing organisms. Given the phylogenetic tree, ancestral population subdivisions are inferred to be those that require the minimum amount of change.

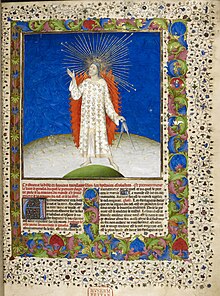

Religion

In the philosophy of religion, Occam's razor is sometimes applied to the existence of God. William of Ockham himself was a Christian. He believed in God, and in the authority of Scripture; he writes that "nothing ought to be posited without a reason given, unless it is self-evident (literally, known through itself) or known by experience or proved by the authority of Sacred Scripture." Ockham believed that an explanation has no sufficient basis in reality when it does not harmonize with reason, experience, or the Bible. However, unlike many theologians of his time, Ockham did not believe God could be logically proven with arguments. To Ockham, science was a matter of discovery, but theology was a matter of revelation and faith. He states: "only faith gives us access to theological truths. The ways of God are not open to reason, for God has freely chosen to create a world and establish a way of salvation within it apart from any necessary laws that human logic or rationality can uncover."

St. Thomas Aquinas, in the Summa Theologica, uses a formulation of Occam's razor to construct an objection to the idea that God exists, which he refutes directly with a counterargument:

Further, it is superfluous to suppose that what can be accounted for by a few principles has been produced by many. But it seems that everything we see in the world can be accounted for by other principles, supposing God did not exist. For all natural things can be reduced to one principle which is nature; and all voluntary things can be reduced to one principle which is human reason, or will. Therefore there is no need to suppose God's existence.

In turn, Aquinas answers this with the quinque viae, and addresses the particular objection above with the following answer:

Since nature works for a determinate end under the direction of a higher agent, whatever is done by nature must needs be traced back to God, as to its first cause. So also whatever is done voluntarily must also be traced back to some higher cause other than human reason or will, since these can change or fail; for all things that are changeable and capable of defect must be traced back to an immovable and self-necessary first principle, as was shown in the body of the Article.

Rather than argue for the necessity of a god, some theists base their belief upon grounds independent of, or prior to, reason, making Occam's razor irrelevant. This was the stance of Søren Kierkegaard, who viewed belief in God as a leap of faith that sometimes directly opposed reason. This is also the doctrine of Gordon Clark's presuppositional apologetics, with the exception that Clark never thought the leap of faith was contrary to reason.

Various arguments in favor of God establish God as a useful or even necessary assumption. Contrastingly some anti-theists hold firmly to the belief that assuming the existence of God introduces unnecessary complexity (Schmitt 2005, e.g., the Ultimate Boeing 747 gambit).

Another application of the principle is to be found in the work of George Berkeley (1685–1753). Berkeley was an idealist who believed that all of reality could be explained in terms of the mind alone. He invoked Occam's razor against materialism, stating that matter was not required by his metaphysic and was thus eliminable. One potential problem with this belief is that it's possible, given Berkeley's position, to find solipsism itself more in line with the razor than a God-mediated world beyond a single thinker.

Occam's razor may also be recognized in the apocryphal story about an exchange between Pierre-Simon Laplace and Napoleon. It is said that in praising Laplace for one of his recent publications, the emperor asked how it was that the name of God, which featured so frequently in the writings of Lagrange, appeared nowhere in Laplace's. At that, he is said to have replied, "It's because I had no need of that hypothesis." Though some points of this story illustrate Laplace's atheism, more careful consideration suggests that he may instead have intended merely to illustrate the power of methodological naturalism, or even simply that the fewer logical premises one assumes, the stronger is one's conclusion.

Philosophy of mind

In his article "Sensations and Brain Processes" (1959), J. J. C. Smart invoked Occam's razor with the aim to justify his preference of the mind-brain identity theory over spirit-body dualism. Dualists state that there are two kinds of substances in the universe: physical (including the body) and spiritual, which is non-physical. In contrast, identity theorists state that everything is physical, including consciousness, and that there is nothing nonphysical. Though it is impossible to appreciate the spiritual when limiting oneself to the physical, Smart maintained that identity theory explains all phenomena by assuming only a physical reality. Subsequently, Smart has been severely criticized for his use (or misuse) of Occam's razor and ultimately retracted his advocacy of it in this context. Paul Churchland (1984) states that by itself Occam's razor is inconclusive regarding duality. In a similar way, Dale Jacquette (1994) stated that Occam's razor has been used in attempts to justify eliminativism and reductionism in the philosophy of mind. Eliminativism is the thesis that the ontology of folk psychology including such entities as "pain", "joy", "desire", "fear", etc., are eliminable in favor of an ontology of a completed neuroscience.

Penal ethics

In penal theory and the philosophy of punishment, parsimony refers specifically to taking care in the distribution of punishment in order to avoid excessive punishment. In the utilitarian approach to the philosophy of punishment, Jeremy Bentham's "parsimony principle" states that any punishment greater than is required to achieve its end is unjust. The concept is related but not identical to the legal concept of proportionality. Parsimony is a key consideration of the modern restorative justice, and is a component of utilitarian approaches to punishment, as well as the prison abolition movement. Bentham believed that true parsimony would require punishment to be individualised to take account of the sensibility of the individual—an individual more sensitive to punishment should be given a proportionately lesser one, since otherwise needless pain would be inflicted. Later utilitarian writers have tended to abandon this idea, in large part due to the impracticality of determining each alleged criminal's relative sensitivity to specific punishments.

Probability theory and statistics

Marcus Hutter's universal artificial intelligence builds upon Solomonoff's mathematical formalization of the razor to calculate the expected value of an action.

There are various papers in scholarly journals deriving formal versions of Occam's razor from probability theory, applying it in statistical inference, and using it to come up with criteria for penalizing complexity in statistical inference. Papers have suggested a connection between Occam's razor and Kolmogorov complexity.

One of the problems with the original formulation of the razor is that it only applies to models with the same explanatory power (i.e., it only tells us to prefer the simplest of equally good models). A more general form of the razor can be derived from Bayesian model comparison, which is based on Bayes factors and can be used to compare models that don't fit the observations equally well. These methods can sometimes optimally balance the complexity and power of a model. Generally, the exact Occam factor is intractable, but approximations such as Akaike information criterion, Bayesian information criterion, Variational Bayesian methods, false discovery rate, and Laplace's method are used. Many artificial intelligence researchers are now employing such techniques, for instance through work on Occam Learning or more generally on the Free energy principle.

Statistical versions of Occam's razor have a more rigorous formulation than what philosophical discussions produce. In particular, they must have a specific definition of the term simplicity, and that definition can vary. For example, in the Kolmogorov–Chaitin minimum description length approach, the subject must pick a Turing machine whose operations describe the basic operations believed to represent "simplicity" by the subject. However, one could always choose a Turing machine with a simple operation that happened to construct one's entire theory and would hence score highly under the razor. This has led to two opposing camps: one that believes Occam's razor is objective, and one that believes it is subjective.

Objective razor

The minimum instruction set of a universal Turing machine requires approximately the same length description across different formulations, and is small compared to the Kolmogorov complexity of most practical theories. Marcus Hutter has used this consistency to define a "natural" Turing machine of small size as the proper basis for excluding arbitrarily complex instruction sets in the formulation of razors. Describing the program for the universal program as the "hypothesis", and the representation of the evidence as program data, it has been formally proven under Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory that "the sum of the log universal probability of the model plus the log of the probability of the data given the model should be minimized." Interpreting this as minimising the total length of a two-part message encoding model followed by data given model gives us the minimum message length (MML) principle.

One possible conclusion from mixing the concepts of Kolmogorov complexity and Occam's razor is that an ideal data compressor would also be a scientific explanation/formulation generator. Some attempts have been made to re-derive known laws from considerations of simplicity or compressibility.

According to Jürgen Schmidhuber, the appropriate mathematical theory of Occam's razor already exists, namely, Solomonoff's theory of optimal inductive inference and its extensions. See discussions in David L. Dowe's "Foreword re C. S. Wallace" for the subtle distinctions between the algorithmic probability work of Solomonoff and the MML work of Chris Wallace, and see Dowe's "MML, hybrid Bayesian network graphical models, statistical consistency, invariance and uniqueness" both for such discussions and for (in section 4) discussions of MML and Occam's razor. For a specific example of MML as Occam's razor in the problem of decision tree induction, see Dowe and Needham's "Message Length as an Effective Ockham's Razor in Decision Tree Induction".

Controversial aspects

Occam's razor is not an embargo against the positing of any kind of entity, or a recommendation of the simplest theory come what may. Occam's razor is used to adjudicate between theories that have already passed "theoretical scrutiny" tests and are equally well-supported by evidence. Furthermore, it may be used to prioritize empirical testing between two equally plausible but unequally testable hypotheses; thereby minimizing costs and wastes while increasing chances of falsification of the simpler-to-test hypothesis.

Another contentious aspect of the razor is that a theory can become more complex in terms of its structure (or syntax), while its ontology (or semantics) becomes simpler, or vice versa. Quine, in a discussion on definition, referred to these two perspectives as "economy of practical expression" and "economy in grammar and vocabulary", respectively.

Galileo Galilei lampooned the misuse of Occam's razor in his Dialogue. The principle is represented in the dialogue by Simplicio. The telling point that Galileo presented ironically was that if one really wanted to start from a small number of entities, one could always consider the letters of the alphabet as the fundamental entities, since one could construct the whole of human knowledge out of them.

Anti-razors

Occam's razor has met some opposition from people who have considered it too extreme or rash. Walter Chatton (c. 1290–1343) was a contemporary of William of Ockham who took exception to Occam's razor and Ockham's use of it. In response he devised his own anti-razor: "If three things are not enough to verify an affirmative proposition about things, a fourth must be added, and so on." Although there have been a number of philosophers who have formulated similar anti-razors since Chatton's time, no one anti-razor has perpetuated in as much notability as Chatton's anti-razor, although this could be the case of the Late Renaissance Italian motto of unknown attribution Se non è vero, è ben trovato ("Even if it is not true, it is well conceived") when referred to a particularly artful explanation.

Anti-razors have also been created by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), and Karl Menger (1902–1985). Leibniz's version took the form of a principle of plenitude, as Arthur Lovejoy has called it: the idea being that God created the most varied and populous of possible worlds. Kant felt a need to moderate the effects of Occam's razor and thus created his own counter-razor: "The variety of beings should not rashly be diminished."

Karl Menger found mathematicians to be too parsimonious with regard to variables, so he formulated his Law Against Miserliness, which took one of two forms: "Entities must not be reduced to the point of inadequacy" and "It is vain to do with fewer what requires more." A less serious but even more extremist anti-razor is 'Pataphysics, the "science of imaginary solutions" developed by Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). Perhaps the ultimate in anti-reductionism, "'Pataphysics seeks no less than to view each event in the universe as completely unique, subject to no laws but its own." Variations on this theme were subsequently explored by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges in his story/mock-essay "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius". Physicist R. V. Jones contrived Crabtree's Bludgeon, which states that "[n]o set of mutually inconsistent observations can exist for which some human intellect cannot conceive a coherent explanation, however complicated."