Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current Homo sapiens from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by abstract thinking, planning depth, symbolic behavior (e.g., art, ornamentation), music and dance, exploitation of large game, and blade technology, among others. Underlying these behaviors and technological innovations are cognitive and cultural foundations that have been documented experimentally and ethnographically by evolutionary and cultural anthropologists. These human universal patterns include cumulative cultural adaptation, social norms, language, and extensive help and cooperation beyond close kin.

Within the tradition of evolutionary anthropology and related disciplines, it has been argued that the development of these modern behavioral traits, in combination with the climatic conditions of the Last Glacial Period and Last Glacial Maximum causing population bottlenecks, contributed to the evolutionary success of Homo sapiens worldwide relative to Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other archaic humans.

Arising from differences in the archaeological record, debate continues as to whether anatomically modern humans were behaviorally modern as well. There are many theories on the evolution of behavioral modernity. These generally fall into two camps: gradualist and cognitive approaches. The Later Upper Paleolithic Model theorises that modern human behavior arose through cognitive, genetic changes in Africa abruptly around 40,000–50,000 years ago around the time of the Out-of-Africa migration, prompting the movement of modern humans out of Africa and across the world. Other models focus on how modern human behavior may have arisen through gradual steps, with the archaeological signatures of such behavior appearing only through demographic or subsistence-based changes. Many cite evidence of behavioral modernity earlier (by at least about 150,000–75,000 years ago and possibly earlier) namely in the African Middle Stone Age. Sally McBrearty and Alison S. Brooks are notable proponents of gradualism, challenging European-centric models by situating more change in the Middle Stone Age of African pre-history, though this version of the story is more difficult to develop in concrete terms due to a thinning fossil record as one goes further back in time.

Definition

To classify what should be included in modern human behavior, it is necessary to define behaviors that are universal among living human groups. Some examples of these human universals are abstract thought, planning, trade, cooperative labor, body decoration, and the control and use of fire. Along with these traits, humans possess much reliance on social learning. This cumulative cultural change or cultural "ratchet" separates human culture from social learning in animals. As well, a reliance on social learning may be responsible in part for humans' rapid adaptation to many environments outside of Africa. Since cultural universals are found in all cultures including some of the most isolated indigenous groups, these traits must have evolved or have been invented in Africa prior to the exodus.

Archaeologically, a number of empirical traits have been used as indicators of modern human behavior. While these are often debated a few are generally agreed upon. Archaeological evidence of behavioral modernity includes:

- Burial

- Fishing

- Figurative art (cave paintings, petroglyphs, dendroglyphs, figurines)

- Systematic use of pigment (such as ochre) and jewelry for decoration or self-ornamentation

- Using bone material for tools

- Transport of resources over long distances

- Blade technology

- Diversity, standardization, and regionally distinct artifacts

- Hearths

- Composite tools

Critiques

Several critiques have been placed against the traditional concept of behavioral modernity, both methodologically and philosophically. Shea (2011) outlines a variety of problems with this concept, arguing instead for "behavioral variability", which, according to the author, better describes the archaeological record. The use of trait lists, according to Shea (2011), runs the risk of taphonomic bias, where some sites may yield more artifacts than others despite similar populations; as well, trait lists can be ambiguous in how behaviors may be empirically recognized in the archaeological record. Shea (2011) in particular cautions that population pressure, cultural change, or optimality models, like those in human behavioral ecology, might better predict changes in tool types or subsistence strategies than a change from "archaic" to "modern" behavior. Some researchers argue that a greater emphasis should be placed on identifying only those artifacts which are unquestionably, or purely, symbolic as a metric for modern human behavior.

Theories and models

−10 — – −9.5 — – −9 — – −8.5 — – −8 — – −7.5 — – −7 — – −6.5 — – −6 — – −5.5 — – −5 — – −4.5 — – −4 — – −3.5 — – −3 — – −2.5 — – −2 — – −1.5 — – −1 — – −0.5 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||

Late Upper Paleolithic Model or "Upper Paleolithic Revolution"

The Late Upper Paleolithic Model, or Upper Paleolithic Revolution, refers to the idea that, though anatomically modern humans first appear around 150,000 years ago (as was once believed), they were not cognitively or behaviorally "modern" until around 50,000 years ago, leading to their expansion out of Africa and into Europe and Asia. These authors note that traits used as a metric for behavioral modernity do not appear as a package until around 40–50,000 years ago. Klein (1995) specifically describes evidence of fishing, bone shaped as a tool, hearths, significant artifact diversity, and elaborate graves are all absent before this point. According to these authors, art only becomes common beyond this switching point, signifying a change from archaic to modern humans. Most researchers argue that a neurological or genetic change, perhaps one enabling complex language, such as FOXP2, caused this revolutionary change in humans.

Alternative models

Contrasted with this view of a spontaneous leap in cognition among ancient humans, some authors like Alison S. Brooks, primarily working in African archaeology, point to the gradual accumulation of "modern" behaviors, starting well before the 50,000 year benchmark of the Upper Paleolithic Revolution models. Howiesons Poort, Blombos, and other South African archaeological sites, for example, show evidence of marine resource acquisition, trade, the making of bone tools, blade and microlith technology, and abstract ornamentation at least by 80,000 years ago. Given evidence from Africa and the Middle East, a variety of hypotheses have been put forth to describe an earlier, gradual transition from simple to more complex human behavior. Some authors have pushed back the appearance of fully modern behavior to around 80,000 years ago or earlier in order to incorporate the South African data.

Others focus on the slow accumulation of different technologies and behaviors across time. These researchers describe how anatomically modern humans could have been cognitively the same and what we define as behavioral modernity is just the result of thousands of years of cultural adaptation and learning. D'Errico and others have looked at Neanderthal culture, rather than early human behavior exclusively, for clues into behavioral modernity. Noting that Neanderthal assemblages often portray traits similar to those listed for modern human behavior, researchers stress that the foundations for behavioral modernity may in fact lie deeper in our hominin ancestors. If both modern humans and Neanderthals express abstract art and complex tools then "modern human behavior" cannot be a derived trait for our species. They argue that the original "human revolution" theory reflects a profound Eurocentric bias. Recent archaeological evidence, they argue, proves that humans evolving in Africa some 300,000 or even 400,000 years ago were already becoming cognitively and behaviourally "modern". These features include blade and microlithic technology, bone tools, increased geographic range, specialized hunting, the use of aquatic resources, long distance trade, systematic processing and use of pigment, and art and decoration. These items do not occur suddenly together as predicted by the "human revolution" model, but at sites that are widely separated in space and time. This suggests a gradual assembling of the package of modern human behaviours in Africa, and its later export to other regions of the Old World.

Between these extremes is the view – currently supported by archaeologists Chris Henshilwood, Curtis Marean, Ian Watts and others – that there was indeed some kind of 'human revolution' but that it occurred in Africa and spanned tens of thousands of years. The term "revolution" in this context would mean not a sudden mutation but a historical development along the lines of "the industrial revolution" or "the Neolithic revolution". In other words, it was a relatively accelerated process, too rapid for ordinary Darwinian "descent with modification" yet too gradual to be attributed to a single genetic or other sudden event. These archaeologists point in particular to the relatively explosive emergence of ochre crayons and shell necklaces apparently used for cosmetic purposes. These archaeologists see symbolic organisation of human social life as the key transition in modern human evolution. Recently discovered at sites such as Blombos Cave and Pinnacle Point, South Africa, pierced shells, pigments and other striking signs of personal ornamentation have been dated within a time-window of 70,000–160,000 years ago in the African Middle Stone Age, suggesting that the emergence of Homo sapiens coincided, after all, with the transition to modern cognition and behaviour. While viewing the emergence of language as a 'revolutionary' development, this school of thought generally attributes it to cumulative social, cognitive and cultural evolutionary processes as opposed to a single genetic mutation.

A further view, taken by archaeologists such as Francesco D'Errico and João Zilhão, is a multi-species perspective arguing that evidence for symbolic culture in the form of utilised pigments and pierced shells are also found in Neanderthal sites, independently of any "modern" human influence.

Cultural evolutionary models may also shed light on why although evidence of behavioral modernity exists before 50,000 years ago it is not expressed consistently until that point. With small population sizes, human groups would have been affected by demographic and cultural evolutionary forces that may not have allowed for complex cultural traits. According to some authors until population density became significantly high, complex traits could not have been maintained effectively. Some genetic evidence supports a dramatic increase in population size before human migration out of Africa. High local extinction rates within a population also can significantly decrease the amount of diversity in neutral cultural traits, regardless of cognitive ability.

Highly speculatively, bicameral mind theory argues for an additional, and cultural rather than genetic, shift from selfless to self-perceiving forms of human cognition and behavior very late in human history, in the Bronze Age. This is based on a literary analysis of Bronze Age texts which claims to show the first appearances of the concept of self around this time, replacing the voices of gods as the primary form of recorded human cognition. This non-mainstream theory is not widely accepted but does receive serious academic interest from time to time.

Archaeological evidence

Africa

Recent research indicates that Homo sapiens originated in Africa between around 350,000 and 260,000 years ago. There is some evidence for the beginning of modern behavior among early African H. sapiens around that period.

Before the Out of Africa theory was generally accepted, there was no consensus on where the human species evolved and, consequently, where modern human behavior arose. Now, however, African archaeology has become extremely important in discovering the origins of humanity. The first Cro-Magnon expansion into Europe around 48,000 years ago is generally accepted as already "modern", and it is now generally believed that behavioral modernity appeared in Africa before 50,000 years ago, either significantly earlier, or possibly as a late Upper Paleolithic "revolution" soon before which prompted migration out of Africa.

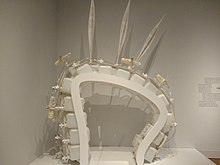

A variety of evidence of abstract imagery, widened subsistence strategies, and other "modern" behaviors have been discovered in Africa, especially South, North, and East Africa. The Blombos Cave site in South Africa, for example, is famous for rectangular slabs of ochre engraved with geometric designs. Using multiple dating techniques, the site was dated to be around 77,000 and 100,000 to 75,000 years old. Ostrich egg shell containers engraved with geometric designs dating to 60,000 years ago were found at Diepkloof, South Africa. Beads and other personal ornamentation have been found from Morocco which might be as much as 130,000 years old; as well, the Cave of Hearths in South Africa has yielded a number of beads dating from significantly prior to 50,000 years ago, and shell beads dating to about 75,000 years ago have been found at Blombos Cave, South Africa.

Specialized projectile weapons as well have been found at various sites in Middle Stone Age Africa, including bone and stone arrowheads at South African sites such as Sibudu Cave (along with an early bone needle also found at Sibudu) dating approximately 72,000-60,000 years ago on some of which poisons may have been used, and bone harpoons at the Central African site of Katanda dating to about 90,000 years ago. Evidence also exists for the systematic heat treating of silcrete stone to increased its flake-ability for the purpose of toolmaking, beginning approximately 164,000 years ago at the South African site of Pinnacle Point and becoming common there for the creation of microlithic tools at about 72,000 years ago.

In 2008, an ochre processing workshop likely for the production of paints was uncovered dating to ca. 100,000 years ago at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Analysis shows that a liquefied pigment-rich mixture was produced and stored in the two abalone shells, and that ochre, bone, charcoal, grindstones and hammer-stones also formed a composite part of the toolkits. Evidence for the complexity of the task includes procuring and combining raw materials from various sources (implying they had a mental template of the process they would follow), possibly using pyrotechnology to facilitate fat extraction from bone, using a probable recipe to produce the compound, and the use of shell containers for mixing and storage for later use. Modern behaviors, such as the making of shell beads, bone tools and arrows, and the use of ochre pigment, are evident at a Kenyan site by 78,000-67,000 years ago. Evidence of early stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, and date to around 279,000 years ago.

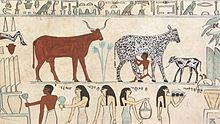

Expanding subsistence strategies beyond big-game hunting and the consequential diversity in tool types has been noted as signs of behavioral modernity. A number of South African sites have shown an early reliance on aquatic resources from fish to shellfish. Pinnacle Point, in particular, shows exploitation of marine resources as early as 120,000 years ago, perhaps in response to more arid conditions inland. Establishing a reliance on predictable shellfish deposits, for example, could reduce mobility and facilitate complex social systems and symbolic behavior. Blombos Cave and Site 440 in Sudan both show evidence of fishing as well. Taphonomic change in fish skeletons from Blombos Cave have been interpreted as capture of live fish, clearly an intentional human behavior.

Humans in North Africa (Nazlet Sabaha, Egypt) are known to have dabbled in chert mining, as early as ≈100,000 years ago, for the construction of stone tools.

Evidence was found in 2018, dating to about 320,000 years ago, at the Kenyan site of Olorgesailie, of the early emergence of modern behaviors including: long-distance trade networks (involving goods such as obsidian), the use of pigments, and the possible making of projectile points. It is observed by the authors of three 2018 studies on the site, that the evidence of these behaviors is approximately contemporary to the earliest known Homo sapiens fossil remains from Africa (such as at Jebel Irhoud and Florisbad), and they suggest that complex and modern behaviors had already begun in Africa around the time of the emergence of anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

In 2019, further evidence of early complex projectile weapons in Africa was found at Aduma, Ethiopia, dated 100,000-80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.

Olduvai Hominid 1 wore facial piercings.

Europe

While traditionally described as evidence for the later Upper Paleolithic Model, European archaeology has shown that the issue is more complex. A variety of stone tool technologies are present at the time of human expansion into Europe and show evidence of modern behavior. Despite the problems of conflating specific tools with cultural groups, the Aurignacian tool complex, for example, is generally taken as a purely modern human signature. The discovery of "transitional" complexes, like "proto-Aurignacian", have been taken as evidence of human groups progressing through "steps of innovation". If, as this might suggest, human groups were already migrating into eastern Europe around 40,000 years and only afterward show evidence of behavioral modernity, then either the cognitive change must have diffused back into Africa or was already present before migration.

In light of a growing body of evidence of Neanderthal culture and tool complexes some researchers have put forth a "multiple species model" for behavioral modernity. Neanderthals were often cited as being an evolutionary dead-end, apish cousins who were less advanced than their human contemporaries. Personal ornaments were relegated as trinkets or poor imitations compared to the cave art produced by H. sapiens. Despite this, European evidence has shown a variety of personal ornaments and artistic artifacts produced by Neanderthals; for example, the Neanderthal site of Grotte du Renne has produced grooved bear, wolf, and fox incisors, ochre and other symbolic artifacts. Although burials are few and controversial, there has been circumstantial evidence of Neanderthal ritual burials. There are two options to describe this symbolic behavior among Neanderthals: they copied cultural traits from arriving modern humans or they had their own cultural traditions comparative with behavioral modernity. If they just copied cultural traditions, which is debated by several authors, they still possessed the capacity for complex culture described by behavioral modernity. As discussed above, if Neanderthals also were "behaviorally modern" then it cannot be a species-specific derived trait.

Asia

Most debates surrounding behavioral modernity have been focused on Africa or Europe but an increasing amount of focus has been placed on East Asia. This region offers a unique opportunity to test hypotheses of multi-regionalism, replacement, and demographic effects. Unlike Europe, where initial migration occurred around 50,000 years ago, human remains have been dated in China to around 100,000 years ago. This early evidence of human expansion calls into question behavioral modernity as an impetus for migration.

Stone tool technology is particularly of interest in East Asia. Following Homo erectus migrations out of Africa, Acheulean technology never seems to appear beyond present-day India and into China. Analogously, Mode 3, or Levallois technology, is not apparent in China following later hominin dispersals. This lack of more advanced technology has been explained by serial founder effects and low population densities out of Africa. Although tool complexes comparative to Europe are missing or fragmentary, other archaeological evidence shows behavioral modernity. For example, the peopling of the Japanese archipelago offers an opportunity to investigate the early use of watercraft. Although one site, Kanedori in Honshu, does suggest the use of watercraft as early as 84,000 years ago, there is no other evidence of hominins in Japan until 50,000 years ago.

The Zhoukoudian cave system near Beijing has been excavated since the 1930s and has yielded precious data on early human behavior in East Asia. Although disputed, there is evidence of possible human burials and interred remains in the cave dated to around 34-20,000 years ago. These remains have associated personal ornaments in the form of beads and worked shell, suggesting symbolic behavior. Along with possible burials, numerous other symbolic objects like punctured animal teeth and beads, some dyed in red ochre, have all been found at Zhoukoudian. Although fragmentary, the archaeological record of eastern Asia shows evidence of behavioral modernity before 50,000 years ago but, like the African record, it is not fully apparent until that time.

See also

- Archaic Homo sapiens

- Blombos Cave

- Cultural universal

- Dawn of Humanity (film)

- Evolution of human intelligence

- Female cosmetic coalitions

- FOXP2 and human evolution

- Human evolution

- List of Stone Age art

- Origin of language

- Origins of society

- Prehistoric art

- Prehistoric music

- Paleolithic religion

- Recent African origin

- Sibudu Cave

- Sociocultural evolution

- Symbolism (disambiguation)

- Symbolic culture

- Timeline of evolution