| Restless legs syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Willis–Ekbom disease (WED), Wittmaack–Ekbom syndrome |

| |

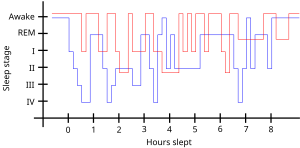

| Sleep pattern of a person with restless legs syndrome (red) compared to a healthy sleep pattern (blue) | |

| Specialty | Sleep medicine |

| Symptoms | Unpleasant feeling in the legs that briefly improves with moving them |

| Complications | Daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, sadness |

| Usual onset | More common with older age |

| Risk factors | Low iron levels, kidney failure, Parkinson's disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, certain medications |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medication |

| Medication | Levodopa, dopamine agonists, gabapentin |

| Frequency | 2.5–15% (US) |

Restless legs syndrome (RLS), now known as Willis-Ekbom Disease (WED), is generally a long-term disorder that causes a strong urge to move one's legs. There is often an unpleasant feeling in the legs that improves somewhat by moving them. This is often described as aching, tingling, or crawling in nature. Occasionally, arms may also be affected. The feelings generally happen when at rest and therefore can make it hard to sleep. Due to the disturbance in sleep, people with RLS may have daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability and a depressed mood. Additionally, many have limb twitching during sleep. RLS is not the same as habitual foot tapping or leg rocking.

Risk factors for RLS include low iron levels, kidney failure, Parkinson's disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy and celiac disease. A number of medications may also trigger the disorder including antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihistamines, and calcium channel blockers. There are two main types. One is early onset RLS which starts before age 45, runs in families and worsens over time. The other is late onset RLS which begins after age 45, starts suddenly, and does not worsen. Diagnosis is generally based on a person's symptoms after ruling out other potential causes.

Restless leg syndrome may resolve if the underlying problem is addressed. Otherwise treatment includes lifestyle changes and medication. Lifestyle changes that may help include stopping alcohol and tobacco use, and sleep hygiene. Medications used include levodopa or a dopamine agonist such as pramipexole. RLS affects an estimated 2.5–15% of the American population. Females are more commonly affected than males, and it becomes increasingly common with age.

Signs and symptoms

RLS sensations range from pain or an aching in the muscles, to "an itch you can't scratch", a "buzzing sensation", an unpleasant "tickle that won't stop", a "crawling" feeling, or limbs jerking while awake. The sensations typically begin or intensify during quiet wakefulness, such as when relaxing, reading, studying, or trying to sleep.

It is a "spectrum" disease with some people experiencing only a minor annoyance and others having major disruption of sleep and impairments in quality of life.

The sensations—and the need to move—may return immediately after ceasing movement or at a later time. RLS may start at any age, including childhood, and is a progressive disease for some, while the symptoms may remit in others. In a survey among members of the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation, it was found that up to 45% of patients had their first symptoms before the age of 20 years.

- "An urge to move, usually due to uncomfortable sensations that occur primarily in the legs, but occasionally in the arms or elsewhere."

- The sensations are unusual and unlike other common sensations. Those with RLS have a hard time describing them, using words or phrases such as uncomfortable, painful, 'antsy', electrical, creeping, itching, pins and needles, pulling, crawling, buzzing, and numbness. It is sometimes described similar to a limb 'falling asleep' or an exaggerated sense of positional awareness of the affected area. The sensation and the urge can occur in any body part; the most cited location is legs, followed by arms. Some people have little or no sensation, yet still, have a strong urge to move.

- "Motor restlessness, expressed as activity, which relieves the urge to move."

- Movement usually brings immediate relief, although temporary and partial. Walking is most common; however, stretching, yoga, biking, or other physical activity may relieve the symptoms. Continuous, fast up-and-down movements of the leg, and/or rapidly moving the legs toward then away from each other, may keep sensations at bay without having to walk. Specific movements may be unique to each person.

- "Worsening of symptoms by relaxation."

- Sitting or lying down (reading, plane ride, watching TV) can trigger the sensations and urge to move. Severity depends on the severity of the person's RLS, the degree of restfulness, duration of the inactivity, etc.

- "Variability over the course of the day-night cycle, with symptoms worse in the evening and early in the night."

- Some experience RLS only at bedtime, while others experience it throughout the day and night. Most people experience the worst symptoms in the evening and the least in the morning.

- "Restless legs feel similar to the urge to yawn, situated in the legs or arms."

- These symptoms of RLS can make sleeping difficult for many patients and a recent poll shows the presence of significant daytime difficulties resulting from this condition. These problems range from being late for work to missing work or events because of drowsiness. Patients with RLS who responded reported driving while drowsy more than patients without RLS. These daytime difficulties can translate into safety, social and economic issues for the patient and for society.

RLS may contribute to higher rates of depression and anxiety disorders in RLS patients.

Primary and secondary

RLS is categorized as either primary or secondary.

- Primary RLS is considered idiopathic or with no known cause. Primary RLS usually begins slowly, before approximately 40–45 years of age and may disappear for months or even years. It is often progressive and gets worse with age. RLS in children is often misdiagnosed as growing pains.

- Secondary RLS often has a sudden onset after age 40, and may be daily from the beginning. It is most associated with specific medical conditions or the use of certain drugs (see below).

Causes

While the cause is generally unknown, it is believed to be caused by changes in the nerve transmitter dopamine resulting in an abnormal use of iron by the brain. RLS is often due to iron deficiency (low total body iron status). Other associated conditions may include end-stage kidney disease and hemodialysis, folate deficiency, magnesium deficiency, sleep apnea, diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson's disease, and certain autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis. RLS can worsen in pregnancy, possibly due to elevated estrogen levels. Use of alcohol, nicotine products, and caffeine may be associated with RLS. A 2014 study from the American Academy of Neurology also found that reduced leg oxygen levels were strongly associated with Restless Leg Syndrome symptom severity in untreated patients.

ADHD

An association has been observed between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and RLS or periodic limb movement disorder. Both conditions appear to have links to dysfunctions related to the neurotransmitter dopamine, and common medications for both conditions among other systems, affect dopamine levels in the brain. A 2005 study suggested that up to 44% of people with ADHD had comorbid (i.e. coexisting) RLS, and up to 26% of people with RLS had confirmed ADHD or symptoms of the condition.

Medications

Certain medications may cause or worsen RLS, or cause it secondarily, including:

- certain antiemetics (antidopaminergic ones)

- certain antihistamines (especially the sedating, first generation H1 antihistamines often in over-the-counter cold medications)

- many antidepressants (both older TCAs and newer SSRIs)

- antipsychotics and certain anticonvulsants

- a rebound effect of sedative-hypnotic drugs such as a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome from discontinuing benzodiazepine tranquilizers or sleeping pills

- alcohol withdrawal can also cause restless legs syndrome and other movement disorders such as akathisia and parkinsonism usually associated with antipsychotics

- opioid withdrawal is associated with causing and worsening RLS

Both primary and secondary RLS can be worsened by surgery of any kind; however, back surgery or injury can be associated with causing RLS.

The cause vs. effect of certain conditions and behaviors observed in some patients (ex. excess weight, lack of exercise, depression or other mental illnesses) is not well established. Loss of sleep due to RLS could cause the conditions, or medication used to treat a condition could cause RLS.

Genetics

More than 60% of cases of RLS are familial and are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable penetrance.

Research and brain autopsies have implicated both dopaminergic system and iron insufficiency in the substantia nigra. Iron is well understood to be an essential cofactor for the formation of L-dopa, the precursor of dopamine.

Six genetic loci found by linkage are known and listed below. Other than the first one, all of the linkage loci were discovered using an autosomal dominant model of inheritance.

- The first genetic locus was discovered in one large French Canadian family and maps to chromosome 12q. This locus was discovered using an autosomal recessive inheritance model. Evidence for this locus was also found using a transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) in 12 Bavarian families.

- The second RLS locus maps to chromosome 14q and was discovered in one Italian family. Evidence for this locus was found in one French Canadian family. Also, an association study in a large sample 159 trios of European descent showed some evidence for this locus.

- This locus maps to chromosome 9p and was discovered in two unrelated American families. Evidence for this locus was also found by the TDT in a large Bavarian family, in which significant linkage to this locus was found.

- This locus maps to chromosome 20p and was discovered in a large French Canadian family with RLS.

- This locus maps to chromosome 2p and was found in three related families from population isolated in South Tyrol.

- The sixth locus is located on chromosome 16p12.1 and was discovered by Levchenko et al. in 2008.

Three genes, MEIS1, BTBD9 and MAP2K5, were found to be associated to RLS. Their role in RLS pathogenesis is still unclear. More recently, a fourth gene, PTPRD was found to be associated with RLS.

There is also some evidence that periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) are associated with BTBD9 on chromosome 6p21.2, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD. The presence of a positive family history suggests that there may be a genetic involvement in the etiology of RLS.

Mechanism

Although it is only partly understood, pathophysiology of restless legs syndrome may involve dopamine and iron system anomalies. There is also a commonly acknowledged circadian rhythm explanatory mechanism associated with it, clinically shown simply by biomarkers of circadian rhythm, such as body temperature. The interactions between impaired neuronal iron uptake and the functions of the neuromelanin-containing and dopamine-producing cells have roles in RLS development, indicating that iron deficiency might affect the brain dopaminergic transmissions in different ways.

Medial thalamic nuclei may also have a role in RLS as part as the limbic system modulated by the dopaminergic system which may affect pain perception. Improvement of RLS symptoms occurs in people receiving low-dose dopamine agonists.

Diagnosis

There are no specific tests for RLS, but non-specific laboratory tests are used to rule out other causes such as vitamin deficiencies. Five symptoms are used to confirm the diagnosis:

- A strong urge to move the limbs, usually associated with unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations.

- It starts or worsens during inactivity or rest.

- It improves or disappears (at least temporarily) with activity.

- It worsens in the evening or night.

- These symptoms are not caused by any medical or behavioral condition.

These symptoms are not essential, like the ones above, but occur commonly in RLS patients:

- genetic component or family history with RLS

- good response to dopaminergic therapy

- periodic leg movements during day or sleep

- most strongly affected are people who are middle-aged or older

- other sleep disturbances are experienced

- decreased iron stores can be a risk factor and should be assessed

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3), the main symptoms have to be associated with a sleep disturbance or impairment in order to support RLS diagnosis. As stated by this classification, RLS symptoms should begin or worsen when being inactive, be relieved when moving, should happen exclusively or mostly in the evening and at night, not be triggered by other medical or behavioral conditions, and should impair one's quality of life. Generally, both legs are affected, but in some cases there is an asymmetry.

Differential diagnosis

The most common conditions that should be differentiated with RLS include leg cramps, positional discomfort, local leg injury, arthritis, leg edema, venous stasis, peripheral neuropathy, radiculopathy, habitual foot tapping/leg rocking, anxiety, myalgia, and drug-induced akathisia.

Peripheral artery disease and arthritis can also cause leg pain but this usually gets worse with movement.

There are less common differential diagnostic conditions included myelopathy, myopathy, vascular or neurogenic claudication, hypotensive akathisia, orthostatic tremor, painful legs, and moving toes.

Treatment

If RLS is not linked to an underlying cause, its frequency may be reduced by lifestyle modifications such as adopting improving sleep hygiene, regular exercise, and stopping smoking. Medications used may include dopamine agonists or gabapentin in those with daily restless legs syndrome, and opioids for treatment of resistant cases.

Treatment of RLS should not be considered until possible medical causes are ruled out. Secondary RLS may be cured if precipitating medical conditions (anemia) are managed effectively.

Physical measures

Stretching the leg muscles can bring temporary relief. Walking and moving the legs, as the name "restless legs" implies, brings temporary relief. In fact, those with RLS often have an almost uncontrollable need to walk and therefore relieve the symptoms while they are moving. Unfortunately, the symptoms usually return immediately after the moving and walking ceases. A vibratory counter-stimulation device has been found to help some people with primary RLS to improve their sleep.

Iron

There is some evidence that intravenous iron supplementation moderately improves restlessness for people with RLS.

Medications

For those whose RLS disrupts or prevents sleep or regular daily activities, medication may be useful. Evidence supports the use of dopamine agonists including: pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine, and cabergoline. They reduce symptoms, improve sleep quality and quality of life. Levodopa is also effective. However, pergolide and cabergoline are less recommended due to their association with increased risk of valvular heart disease. Ropinirole has a faster onset with shorter duration. Rotigotine is commonly used as a transdermal patch which continuously provides stable plasma drug concentrations, resulting in its particular therapeutic effect on patients with symptoms throughout the day. One review found pramipexole to be better than ropinirole.

There are, however, issues with the use of dopamine agonists including augmentation. This is a medical condition where the drug itself causes symptoms to increase in severity and/or occur earlier in the day. Dopamine agonists may also cause rebound when symptoms increase as the drug wears off. In many cases, the longer dopamine agonists have been used the higher the risk of augmentation and rebound as well as the severity of the symptoms. Also, a recent study indicated that dopamine agonists used in restless leg syndrome can lead to an increase in compulsive gambling.

- Gabapentin or pregabalin, a non-dopaminergic treatment for moderate to severe primary RLS

- Opioids are only indicated in severe cases that do not respond to other measures due to their high rate of side effects, which may include constipation, fatigue and headache.

One possible treatment for RLS is dopamine agonists, unfortunately patients can develop dopamine dysregulation syndrome, meaning that they can experience an addictive pattern of dopamine replacement therapy. Additionally, they can exhibit some behavioral disturbances such as impulse control disorders like pathologic gambling, compulsive purchasing and compulsive eating. There are some indications that stopping the dopamine agonist treatment has an impact on the resolution or at least improvement of the impulse control disorder, even though some people can be particularly exposed to dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome.

Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam or clonazepam, are not generally recommended, and their effectiveness is unknown. They however are sometimes still used as a second line, as add on agents. Quinine is not recommended due to its risk of serious side effects involving the blood.

Prognosis

RLS symptoms may gradually worsen with age, although more slowly for those with the idiopathic form of RLS than for people who also have an associated medical condition. Current therapies can control the disorder, minimizing symptoms and increasing periods of restful sleep. In addition, some people have remissions, periods in which symptoms decrease or disappear for days, weeks, or months, although symptoms usually eventually reappear. Being diagnosed with RLS does not indicate or foreshadow another neurological disease, such as Parkinson's disease. RLS symptoms can worsen over time when dopamine-related drugs are used for therapy, an effect called "augmentation" which may represent symptoms occurring throughout the day and affect movements of all limbs. There is no cure for RLS.

Epidemiology

RLS affects an estimated 2.5–15% of the American population. A minority (around 2.7% of the population) experience daily or severe symptoms. RLS is twice as common in women as in men, and Caucasians are more prone to RLS than people of African descent. RLS occurs in 3% of individuals from the Mediterranean or Middle Eastern regions, and in 1–5% of those from East Asia, indicating that different genetic or environmental factors, including diet, may play a role in the prevalence of this syndrome. RLS diagnosed at an older age runs a more severe course. RLS is even more common in individuals with iron deficiency, pregnancy, or end-stage kidney disease. The National Sleep Foundation's 1998 Sleep in America poll showed that up to 25 percent of pregnant women developed RLS during the third trimester. Poor general health is also linked.

There are several risk factors for RLS, including old age, family history, and uremia. The prevalence of RLS tends to increase with age, as well as its severity and longer duration of symptoms. People with uremia receiving renal dialysis have a prevalence from 20% to 57%, while those having kidney transplant improve compared to those treated with dialysis.

RLS can occur at all ages, although it typically begins in the third or fourth decade. Genome‐wide association studies have now identified 19 risk loci associated with RLS. Neurological conditions linked to RLS include Parkinson's disease, spinal cerebellar atrophy, spinal stenosis, lumbosacral radiculopathy and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2.

History

The first known medical description of RLS was by Sir Thomas Willis in 1672. Willis emphasized the sleep disruption and limb movements experienced by people with RLS. Initially published in Latin (De Anima Brutorum, 1672) but later translated to English (The London Practice of Physick, 1685), Willis wrote:

Wherefore to some, when being abed they betake themselves to sleep, presently in the arms and legs, leapings and contractions on the tendons, and so great a restlessness and tossings of other members ensue, that the diseased are no more able to sleep, than if they were in a place of the greatest torture.

The term "fidgets in the legs" has also been used as early as the early nineteenth century.

Subsequently, other descriptions of RLS were published, including those by François Boissier de Sauvages (1763), Magnus Huss (1849), Theodur Wittmaack (1861), George Miller Beard (1880), Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1898), Hermann Oppenheim (1923) and Frederick Gerard Allison (1943).[90][92] However, it was not until almost three centuries after Willis, in 1945, that Karl-Axel Ekbom (1907–1977) provided a detailed and comprehensive report of this condition in his doctoral thesis, Restless legs: clinical study of hitherto overlooked disease. Ekbom coined the term "restless legs" and continued work on this disorder throughout his career. He described the essential diagnostic symptoms, differential diagnosis from other conditions, prevalence, relation to anemia, and common occurrence during pregnancy.

Ekbom's work was largely ignored until it was rediscovered by Arthur S. Walters and Wayne A. Hening in the 1980s. Subsequent landmark publications include 1995 and 2003 papers, which revised and updated the diagnostic criteria. Journal of Parkinsonism and RLS is the first peer-reviewed, online, open access journal dedicated to publishing research about Parkinson's disease and was founded by a Canadian neurologist Dr. Abdul Qayyum Rana.

Nomenclature

For decades the most widely used name for the disease was restless legs syndrome, and it is still the most commonly used. In 2013 the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation renamed itself the Willis–Ekbom Disease Foundation, and it encourages the use of the name Willis–Ekbom disease; its reasons are quoted as follows:

The name Willis–Ekbom disease:

- Eliminates incorrect descriptors—the condition often involves parts of the body other than legs

- Promotes cross-cultural ease of use

- Responds to trivialization of the disease and humorous treatment in the media

- Acknowledges the first known description by Sir Thomas Willis in 1672 and the first detailed clinical description by Dr. Karl Axel Ekbom in 1945.

A point of confusion is that RLS and delusional parasitosis are entirely different conditions that have both been called "Ekbom syndrome", as both syndromes were described by the same person, Karl-Axel Ekbom. Today, calling WED/RLS "Ekbom syndrome" is outdated usage, as the unambiguous names (WED or RLS) are preferred for clarity.

Controversy

Some doctors express the view that the incidence of restless leg syndrome is exaggerated by manufacturers of drugs used to treat it. Others believe it is an underrecognized and undertreated disorder. Further, GlaxoSmithKline ran advertisements that, while not promoting off-licence use of their drug (ropinirole) for treatment of RLS, did link to the Ekbom Support Group website. That website contained statements advocating the use of ropinirole to treat RLS. The ABPI ruled against GSK in this case.

Research

Different measurements have been used to evaluate treatments in RLS. Most of them are based on subjective rating scores, such as IRLS rating scale (IRLS), Clinical Global Impression (CGI), Patient Global Impression (PGI), and Quality of life (QoL). These questionnaires provide information about the severity and progress of the disease, as well as the person's quality of life and sleep. Polysomnography (PSG) and actigraphy (both related to sleep parameters) are more objective resources that provide evidences of sleep disturbances associated with RLS symptoms.