A prisoner of war (POW) is a combatant or non-combatant—whether a military member, an irregular military fighter, or a civilian—who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war in custody for a range of legitimate and illegitimate reasons, such as isolating them from the enemy combatants still in the field (releasing and repatriating them in an orderly manner after hostilities), demonstrating military victory, punishing them, prosecuting them for war crimes, exploiting them for their labour, recruiting or even conscripting them as their own combatants, collecting military and political intelligence from them, or indoctrinating them in new political or religious beliefs.

Ancient times

For most of human history, depending on the culture of the victors, enemy combatants on the losing side in a battle who had surrendered and been taken as prisoners of war could expect to be either slaughtered or enslaved. Early Roman gladiators could be prisoners of war, categorised according to their ethnic roots as Samnites, Thracians, and Gauls (Galli). Homer's Iliad describes Greek and Trojan soldiers offering rewards of wealth to opposing forces who have defeated them on the battlefield in exchange for mercy, but their offers are not always accepted; see Lycaon for example.

Typically, victors made little distinction between enemy combatants and enemy civilians, although they were more likely to spare women and children. Sometimes the purpose of a battle, if not of a war, was to capture women, a practice known as raptio; the Rape of the Sabines involved, according to tradition, a large mass-abduction by the founders of Rome. Typically women had no rights, and were held legally as chattels.

In the fourth century AD, Bishop Acacius of Amida, touched by the plight of Persian prisoners captured in a recent war with the Roman Empire, who were held in his town under appalling conditions and destined for a life of slavery, took the initiative in ransoming them by selling his church's precious gold and silver vessels and letting them return to their country. For this he was eventually canonized.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

According to legend, during Childeric's siege and blockade of Paris in 464 the nun Geneviève (later canonised as the city's patron saint) pleaded with the Frankish king for the welfare of prisoners of war and met with a favourable response. Later, Clovis I (r. 481–511) liberated captives after Genevieve urged him to do so.

King Henry V's English army killed many French prisoners-of-war after the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. This was done in retaliation for the French killing of the boys and other non-combatants handling the baggage and equipment of the army, and because the French were attacking again and Henry was afraid that they would break through and free the prisoners to fight again.

In the later Middle Ages a number of religious wars aimed to not only defeat but also to eliminate enemies. Authorities in Christian Europe often considered the extermination of heretics and heathens desirable. Examples of such wars include the 13th-century Albigensian Crusade in Languedoc and the Northern Crusades in the Baltic region. When asked by a Crusader how to distinguish between the Catholics and Cathars following the projected capture (1209) of the city of Béziers, the Papal Legate Arnaud Amalric allegedly replied, "Kill them all, God will know His own".

Likewise, the inhabitants of conquered cities were frequently massacred during Christians' Crusades against Muslims in the 11th and 12th centuries. Noblemen could hope to be ransomed; their families would have to send to their captors large sums of wealth commensurate with the social status of the captive.

Feudal Japan had no custom of ransoming prisoners of war, who could expect for the most part summary execution.

In the 13th century the expanding Mongol Empire famously distinguished between cities or towns that surrendered (where the population was spared but required to support the conquering Mongol army) and those that resisted (in which case the city was ransacked and destroyed, and all the population killed). In Termez, on the Oxus: "all the people, both men and women, were driven out onto the plain, and divided in accordance with their usual custom, then they were all slain".

The Aztecs warred constantly with neighbouring tribes and groups, aiming to collect live prisoners for sacrifice. For the re-consecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed.

During the early Muslim conquests of 622–750, Muslims routinely captured large numbers of prisoners. Aside from those who converted, most were ransomed or enslaved. Christians captured during the Crusades were usually either killed or sold into slavery if they could not pay a ransom. During his lifetime (c. 570-632), Muhammad made it the responsibility of the Islamic government to provide food and clothing, on a reasonable basis, to captives, regardless of their religion; however if the prisoners were in the custody of a person, then the responsibility was on the individual. The freeing of prisoners was highly recommended as a charitable act. On certain occasions where Muhammad felt the enemy had broken a treaty with the Muslims he endorsed the mass execution of male prisoners who participated in battles, as in the case of the Banu Qurayza in 627. The Muslims divided up the females and children of those executed as ghanima (spoils of war).

Modern times

In Europe, the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly centralized, in the time period between the 16th and late 18th century. Whereas prisoners of war had previously been regarded as the private property of the captor, captured enemy soldiers became increasingly regarded as the property of the state. The European states strived to exert increasing control over all stages of captivity, from the question of who would be attributed the status of prisoner of war to their eventual release. The act of surrender was regulated so that it, ideally, should be legitimized by officers, who negotiated the surrender of their whole unit. Soldiers whose style of fighting did not conform to the battle line tactics of regular European armies, such as Cossacks and Croats, were often denied the status of prisoners of war.

In line with this development the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly regulated in interactional treaties, particularly in the form of the so called cartel system, which regulated how the exchange of prisoners would be carried out between warring states. Another such treaty was the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years' War. This treaty established the rule that prisoners of war should be released without ransom at the end of hostilities and that they should be allowed to return to their homelands.

There also evolved the right of parole, French for "discourse", in which a captured officer surrendered his sword and gave his word as a gentleman in exchange for privileges. If he swore not to escape, he could gain better accommodations and the freedom of the prison. If he swore to cease hostilities against the nation who held him captive, he could be repatriated or exchanged but could not serve against his former captors in a military capacity.

European settlers captured in North America

Early historical narratives of captured European settlers, including perspectives of literate women captured by the indigenous peoples of North America, exist in some number. The writings of Mary Rowlandson, captured in the chaotic fighting of King Philip's War, are an example. Such narratives enjoyed some popularity, spawning a genre of the captivity narrative, and had lasting influence on the body of early American literature, most notably through the legacy of James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans. Some Native Americans continued to capture Europeans and use them both as labourers and bargaining chips into the 19th century; see for example John R. Jewitt, a sailor who wrote a memoir about his years as a captive of the Nootka people on the Pacific Northwest coast from 1802 to 1805.

French Revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars

The earliest known purposely built prisoner-of-war camp was established at Norman Cross, England in 1797 to house the increasing number of prisoners from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document. Norman Cross Prison was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. The British government went to great lengths to provide food of a quality at least equal to that available to locals. The senior officer from each quadrangle was permitted to inspect the food as it was delivered to the prison to ensure it was of sufficient quality. Despite the generous supply and quality of food, some prisoners died of starvation after gambling away their rations. Most of the men held in the prison were low-ranking soldiers and sailors, including midshipmen and junior officers, with a small number of privateers. About 100 senior officers and some civilians "of good social standing", mainly passengers on captured ships and the wives of some officers, were given parole d'honneur outside the prison, mainly in Peterborough although some further afield in Northampton, Plymouth, Melrose and Abergavenny. They were afforded the courtesy of their rank within English society. During the Battle of Leipzig both sides used the city's cemetery as a lazaret and prisoner camp for around 6000 POWs who lived in the burial vaults and used the coffins for firewood. Food was scarce and prisoners resorted to eating horses, cats, dogs or even human flesh. The bad conditions inside the graveyard contributed to a city-wide epidemic after the battle.

Prisoner exchanges

The extensive period of conflict during the American Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815), followed by the Anglo-American War of 1812, led to the emergence of a cartel system for the exchange of prisoners, even while the belligerents were at war. A cartel was usually arranged by the respective armed service for the exchange of like-ranked personnel. The aim was to achieve a reduction in the number of prisoners held, while at the same time alleviating shortages of skilled personnel in the home country.

American Civil War

At the start of the civil war a system of paroles operated. Captives agreed not to fight until they were officially exchanged. Meanwhile, they were held in camps run by their own army where they were paid but not allowed to perform any military duties. The system of exchanges collapsed in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to exchange black prisoners. In the late summer of 1864, a year after the Dix–Hill Cartel was suspended; Confederate officials approached Union General Benjamin Butler, Union Commissioner of Exchange, about resuming the cartel and including the black prisoners. Butler contacted Grant for guidance on the issue, and Grant responded to Butler on 18 August 1864 with his now famous statement. He rejected the offer, stating in essence, that the Union could afford to leave their men in captivity, the Confederacy could not. After that about 56,000 of the 409,000 POWs died in prisons during the American Civil War, accounting for nearly 10% of the conflict's fatalities. Of the 45,000 Union prisoners of war confined in Camp Sumter, located near Andersonville, Georgia, 13,000 (28%) died. At Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois, 10% of its Confederate prisoners died during one cold winter month; and Elmira Prison in New York state, with a death rate of 25% (2,963), nearly equalled that of Andersonville.

Amelioration

During the 19th century, there were increased efforts to improve the treatment and processing of prisoners. As a result of these emerging conventions, a number of international conferences were held, starting with the Brussels Conference of 1874, with nations agreeing that it was necessary to prevent inhumane treatment of prisoners and the use of weapons causing unnecessary harm. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new conventions being adopted and becoming recognized as international law that specified that prisoners of war be treated humanely and diplomatically.

Hague and Geneva Conventions

Chapter II of the Annex to the 1907 Hague Convention IV – The Laws and Customs of War on Land covered the treatment of prisoners of war in detail. These provisions were further expanded in the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Prisoners of War and were largely revised in the Third Geneva Convention in 1949.

Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention protects captured military personnel, some guerrilla fighters, and certain civilians. It applies from the moment a prisoner is captured until he or she is released or repatriated. One of the main provisions of the convention makes it illegal to torture prisoners and states that a prisoner can only be required to give their name, date of birth, rank and service number (if applicable).

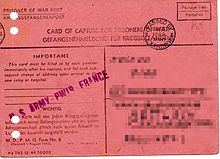

The ICRC has a special role to play, with regards to international humanitarian law, in restoring and maintaining family contact in times of war, in particular concerning the right of prisoners of war and internees to send and receive letters and cards (Geneva Convention (GC) III, art.71 and GC IV, art.107).

However, nations vary in their dedication to following these laws, and historically the treatment of POWs has varied greatly. During World War II, Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany (towards Soviet POWs and Western Allied commandos) were notorious for atrocities against prisoners of war. The German military used the Soviet Union's refusal to sign the Geneva Convention as a reason for not providing the necessities of life to Soviet POWs; and the Soviets also used Axis prisoners as forced labour. The Germans also routinely executed British and American commandos captured behind German lines per the Commando Order. North Korean and North and South Vietnamese forces routinely killed or mistreated prisoners taken during those conflicts.

Qualifications

To be entitled to prisoner-of-war status, captured persons must be lawful combatants entitled to combatant's privilege—which gives them immunity from punishment for crimes constituting lawful acts of war such as killing enemy combatants. To qualify under the Third Geneva Convention, a combatant must be part of a chain of command, wear a "fixed distinctive marking, visible from a distance", bear arms openly, and have conducted military operations according to the laws and customs of war. (The Convention recognizes a few other groups as well, such as "[i]nhabitants of a non-occupied territory, who on the approach of the enemy spontaneously take up arms to resist the invading forces, without having had time to form themselves into regular armed units".)

Thus, uniforms and badges are important in determining prisoner-of-war status under the Third Geneva Convention. Under Additional Protocol I, the requirement of a distinctive marking is no longer included. francs-tireurs, militias, insurgents, terrorists, saboteurs, mercenaries, and spies generally do not qualify because they do not fulfill the criteria of Additional Protocol 1. Therefore, they fall under the category of unlawful combatants, or more properly they are not combatants. Captured soldiers who do not get prisoner of war status are still protected like civilians under the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The criteria are applied primarily to international armed conflicts. The application of prisoner of war status in non-international armed conflicts like civil wars is guided by Additional Protocol II, but insurgents are often treated as traitors, terrorists or criminals by government forces and are sometimes executed on spot or tortured. However, in the American Civil War, both sides treated captured troops as POWs presumably out of reciprocity, although the Union regarded Confederate personnel as separatist rebels. However, guerrillas and other irregular combatants generally cannot expect to receive benefits from both civilian and military status simultaneously.

Rights

Under the Third Geneva Convention, prisoners of war (POW) must be:

- Treated humanely with respect for their persons and their honor

- Able to inform their next of kin and the International Committee of the Red Cross of their capture

- Allowed to communicate regularly with relatives and receive packages

- Given adequate food, clothing, housing, and medical attention

- Paid for work done and not forced to do work that is dangerous, unhealthy, or degrading

- Released quickly after conflicts end

- Not compelled to give any information except for name, age, rank, and service number

In addition, if wounded or sick on the battlefield, the prisoner will receive help from the International Committee of the Red Cross.

When a country is responsible for breaches of prisoner of war rights, those accountable will be punished accordingly. An example of this is the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials. German and Japanese military commanders were prosecuted for preparing and initiating a war of aggression, murder, ill treatment, and deportation of individuals, and genocide during World War II. Most were executed or sentenced to life in prison for their crimes.

U.S. Code of Conduct and terminology

The United States Military Code of Conduct was promulgated in 1955 via Executive Order 10631 under President Dwight D. Eisenhower to serve as a moral code for United States service members who have been taken prisoner. It was created primarily in response to the breakdown of leadership and organization, specifically when U.S. forces were POWs during the Korean War.

When a military member is taken prisoner, the Code of Conduct reminds them that the chain of command is still in effect (the highest ranking service member eligible for command, regardless of service branch, is in command), and requires them to support their leadership. The Code of Conduct also requires service members to resist giving information to the enemy (beyond identifying themselves, that is, "name, rank, serial number"), receiving special favors or parole, or otherwise providing their enemy captors aid and comfort.

Since the Vietnam War, the official U.S. military term for enemy POWs is EPW (Enemy Prisoner of War). This name change was introduced in order to distinguish between enemy and U.S. captives.

In 2000, the U.S. military replaced the designation "Prisoner of War" for captured American personnel with "Missing-Captured". A January 2008 directive states that the reasoning behind this is since "Prisoner of War" is the international legal recognized status for such people there is no need for any individual country to follow suit. This change remains relatively unknown even among experts in the field and "Prisoner of War" remains widely used in the Pentagon which has a "POW/Missing Personnel Office" and awards the Prisoner of War Medal.

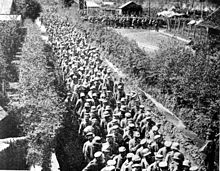

World War I

During World War I, about eight million men surrendered and were held in POW camps until the war ended. All nations pledged to follow the Hague rules on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and in general the POWs had a much higher survival rate than their peers who were not captured. Individual surrenders were uncommon; usually a large unit surrendered all its men. At Tannenberg 92,000 Russians surrendered during the battle. When the besieged garrison of Kaunas surrendered in 1915, 20,000 Russians became prisoners. Over half the Russian losses were prisoners as a proportion of those captured, wounded or killed. About 3.3 million men became prisoners.

The German Empire held 2.5 million prisoners; Russia held 2.9 million, and Britain and France held about 720,000, mostly gained in the period just before the Armistice in 1918. The US held 48,000. The most dangerous moment for POWs was the act of surrender, when helpless soldiers were sometimes mistakenly shot down. Once prisoners reached a POW camp conditions were better (and often much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations.

There was however much harsh treatment of POWs in Germany, as recorded by the American ambassador to Germany (prior to America's entry into the war), James W. Gerard, who published his findings in "My Four Years in Germany". Even worse conditions are reported in the book "Escape of a Princess Pat" by the Canadian George Pearson. It was particularly bad in Russia, where starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; a quarter of the over 2 million POWs held there died. Nearly 375,000 of the 500,000 Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war taken by Russians perished in Siberia from smallpox and typhus. In Germany, food was short, but only 5% died.

The Ottoman Empire often treated prisoners of war poorly. Some 11,800 British soldiers, most of them Indians, became prisoners after the five-month Siege of Kut, in Mesopotamia, in April 1916. Many were weak and starved when they surrendered and 4,250 died in captivity.

During the Sinai and Palestine campaign 217 Australian and unknown numbers of British, New Zealand and Indian soldiers were captured by Ottoman forces. About 50% of the Australian prisoners were light horsemen including 48 missing believed captured on 1 May 1918 in the Jordan Valley. Australian Flying Corps pilots and observers were captured in the Sinai Peninsula, Palestine and the Levant. One third of all Australian prisoners were captured on Gallipoli including the crew of the submarine AE2 which made a passage through the Dardanelles in 1915. Forced marches and crowded railway journeys preceded years in camps where disease, poor diet and inadequate medical facilities prevailed. About 25% of other ranks died, many from malnutrition, while only one officer died.

The most curious case came in Russia where the Czechoslovak Legion of Czechoslovak prisoners (from the Austro-Hungarian army): they were released in 1917, armed themselves, briefly culminating into a military and diplomatic force during the Russian Civil War.

Release of prisoners

At the end of the war in 1918 there were believed to be 140,000 British prisoners of war in Germany, including thousands of internees held in neutral Switzerland. The first British prisoners were released and reached Calais on 15 November. Plans were made for them to be sent via Dunkirk to Dover and a large reception camp was established at Dover capable of housing 40,000 men, which could later be used for demobilisation.

On 13 December 1918, the armistice was extended and the Allies reported that by 9 December 264,000 prisoners had been repatriated. A very large number of these had been released en masse and sent across Allied lines without any food or shelter. This created difficulties for the receiving Allies and many released prisoners died from exhaustion. The released POWs were met by cavalry troops and sent back through the lines in lorries to reception centres where they were refitted with boots and clothing and dispatched to the ports in trains.

Upon arrival at the receiving camp the POWs were registered and "boarded" before being dispatched to their own homes. All commissioned officers had to write a report on the circumstances of their capture and to ensure that they had done all they could to avoid capture. Each returning officer and man was given a message from King George V, written in his own hand and reproduced on a lithograph. It read as follows:

The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries & hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage.

During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant Officers & Men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

We are thankful that this longed for day has arrived, & that back in the old Country you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home & to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return.

George R.I.

While the Allied prisoners were sent home at the end of the war, the same treatment was not granted to Central Powers prisoners of the Allies and Russia, many of whom had to serve as forced labour, e.g. in France, until 1920. They were released after many approaches by the ICRC to the Allied Supreme Council.

World War II

Historian Niall Ferguson, in addition to figures from Keith Lowe, tabulated the total death rate for POWs in World War II as follows:

| Percentage of POWs that Died | |

|---|---|

| USSR POWs held by Germans | 57.5% |

| German POWs held by Yugoslavs | 41.2% |

| German POWs held by USSR | 35.8% |

| American POWs held by Japanese | 33.0% |

| American POWs held by Germans | 1.19% |

| German POWs held by Eastern Europeans | 32.9% |

| British POWs held by Japanese | 24.8% |

| German POWs held by Czechoslovaks | 5.0% |

| British POWs held by Germans | 3.5% |

| German POWs held by French | 2.58% |

| German POWs held by Americans | 0.15% |

| German POWs held by British | 0.03% |

Treatment of POWs by the Axis

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, which had signed but never ratified the 1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War, did not treat prisoners of war in accordance with international agreements, including provisions of the Hague Conventions, either during the Second Sino-Japanese War or during the Pacific War, because the Japanese viewed surrender as dishonorable. Moreover, according to a directive ratified on 5 August 1937 by Hirohito, the constraints of the Hague Conventions were explicitly removed on Chinese prisoners.

Prisoners of war from China, United States, Australia, Britain, Canada, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the Philippines held by Japanese imperial armed forces were subject to murder, beatings, summary punishment, brutal treatment, forced labour, medical experimentation, starvation rations, poor medical treatment and cannibalism. The most notorious use of forced labour was in the construction of the Burma–Thailand Death Railway. After 20 March 1943, the Imperial Navy was under orders to execute all prisoners taken at sea.

After the Armistice of Cassibile, Italian soldiers and civilians in East Asia were taken as prisoners by Japanese armed forces and subject to the same conditions as other POWs.

According to the findings of the Tokyo Tribunal, the death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1%, seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians. The death rate of Chinese was much higher. Thus, while 37,583 prisoners from the United Kingdom, Commonwealth, and Dominions, 28,500 from the Netherlands, and 14,473 from the United States were released after the surrender of Japan, the number for the Chinese was only 56. The 27,465 United States Army and United States Army Air Forces POWs in the Pacific Theater had a 40.4% death rate. The War Ministry in Tokyo issued an order at the end of the war to kill all surviving POWs.

No direct access to the POWs was provided to the International Red Cross. Escapes among Caucasian prisoners were almost impossible because of the difficulty of men of Caucasian descent hiding in Asiatic societies.

Allied POW camps and ship-transports were sometimes accidental targets of Allied attacks. The number of deaths which occurred when Japanese "hell ships"—unmarked transport ships in which POWs were transported in harsh conditions—were attacked by U.S. Navy submarines was particularly high. Gavan Daws has calculated that "of all POWs who died in the Pacific War, one in three was killed on the water by friendly fire". Daws states that 10,800 of the 50,000 POWs shipped by the Japanese were killed at sea while Donald L. Miller states that "approximately 21,000 Allied POWs died at sea, about 19,000 of them killed by friendly fire."

Life in the POW camps was recorded at great risk to themselves by artists such as Jack Bridger Chalker, Philip Meninsky, Ashley George Old, and Ronald Searle. Human hair was often used for brushes, plant juices and blood for paint, and toilet paper as the "canvas". Some of their works were used as evidence in the trials of Japanese war criminals.

Female prisoners (detainees) at Changi prisoner of war camp in Singapore, bravely recorded their defiance in seemingly harmless prison quilt embroidery.

Research into the conditions of the camps has been conducted by The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Troops of the Suffolk Regiment surrendering to the Japanese, 1942

Many US and Filipino POWs died as a result of the Bataan Death March, in May 1942

Water colour sketch of "Dusty" Rhodes by Ashley George Old

U.S. Navy nurses rescued from Los Baños Internment Camp, March 1945

Allied prisoners of war at Aomori camp near Yokohama, Japan waving flags of the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands in August 1945.

Canadian POWs at the Liberation of Hong Kong

POW art depicting Cabanatuan prison camp, produced in 1946

Australian POW Leonard Siffleet captured at New Guinea moments before his execution with a Japanese shin gunto sword in 1943.

Germany

French soldiers

After the French armies surrendered in summer 1940, Germany seized two million French prisoners of war and sent them to camps in Germany. About one third were released on various terms. Of the remainder, the officers and non-commissioned officers were kept in camps and did not work. The privates were sent out to work. About half of them worked for German agriculture, where food supplies were adequate and controls were lenient. The others worked in factories or mines, where conditions were much harsher.

Western Allies' POWs

Germany and Italy generally treated prisoners from the British Empire and Commonwealth, France, the U.S., and other western Allies in accordance with the Geneva Convention, which had been signed by these countries. Consequently, western Allied officers were not usually made to work and some personnel of lower rank were usually compensated, or not required to work either. The main complaints of western Allied prisoners of war in German POW camps—especially during the last two years of the war—concerned shortages of food.

Only a small proportion of western Allied POWs who were Jews—or whom the Nazis believed to be Jewish—were killed as part of the Holocaust or were subjected to other antisemitic policies. For example, Major Yitzhak Ben-Aharon, a Palestinian Jew who had enlisted in the British Army, and who was captured by the Germans in Greece in 1941, experienced four years of captivity under entirely normal conditions for POWs.

However, a small number of Allied personnel were sent to concentration camps, for a variety of reasons including being Jewish. As the US historian Joseph Robert White put it: "An important exception ... is the sub-camp for U.S. POWs at Berga an der Elster, officially called Arbeitskommando 625 [also known as Stalag IX-B]. Berga was the deadliest work detachment for American captives in Germany. 73 men who participated, or 21 percent of the detachment, perished in two months. 80 of the 350 POWs were Jews." Another well-known example was a group of 168 Australian, British, Canadian, New Zealand and US aviators who were held for two months at Buchenwald concentration camp; two of the POWs died at Buchenwald. Two possible reasons have been suggested for this incident: German authorities wanted to make an example of Terrorflieger ("terrorist aviators") or these aircrews were classified as spies, because they had been disguised as civilians or enemy soldiers when they were apprehended.

Information on conditions in the stalags is contradictory depending on the source. Some American POWs claimed the Germans were victims of circumstance and did the best they could, while others accused their captors of brutalities and forced labour. In any case, the prison camps were miserable places where food rations were meager and conditions squalid. One American admitted "The only difference between the stalags and concentration camps was that we weren't gassed or shot in the former. I do not recall a single act of compassion or mercy on the part of the Germans." Typical meals consisted of a bread slice and watery potato soup which, however, was still more substantial than what Soviet POWs or concentration camp inmates received. Another prisoner stated that "The German plan was to keep us alive, yet weakened enough that we wouldn't attempt escape."

As Soviet ground forces approached some POW camps in early 1945, German guards forced western Allied POWs to walk long distances towards central Germany, often in extreme winter weather conditions. It is estimated that, out of 257,000 POWs, about 80,000 were subject to such marches and up to 3,500 of them died as a result.

Italian POWs

In September 1943 after the Armistice, Italian officers and soldiers that in many places waited for clear superior orders were arrested by Germans and Italian fascists and taken to German internment camps in Germany or Eastern Europe, where they were held for the duration of World War II. The International Red Cross could do nothing for them, as they were not regarded as POWs, but the prisoners held the status of "military internees". Treatment of the prisoners was generally poor. The author Giovannino Guareschi was among those interned and wrote about this time in his life. The book was translated and published as My Secret Diary. He wrote about the hungers of semi-starvation, the casual murder of individual prisoners by guards and how, when they were released (now from a German camp), they found a deserted German town filled with foodstuffs that they (with other released prisoners) ate. It is estimated that of the 700,000 Italians taken prisoner by the Germans, around 40,000 died in detention and more than 13,000 lost their lives during the transportation from the Greek islands to the mainland.

Eastern European POWs

Germany did not apply the same standard of treatment to non-western prisoners, especially many Polish and Soviet POWs who suffered harsh conditions and died in large numbers while in captivity.

Between 1941 and 1945 the Axis powers took about 5.7 million Soviet prisoners. About one million of them were released during the war, in that their status changed but they remained under German authority. A little over 500,000 either escaped or were liberated by the Red Army. Some 930,000 more were found alive in camps after the war. The remaining 3.3 million prisoners (57.5% of the total captured) died during their captivity. Between the launching of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941 and the following spring, 2.8 million of the 3.2 million Soviet prisoners taken died while in German hands. According to Russian military historian General Grigoriy Krivosheyev, the Axis powers took 4.6 million Soviet prisoners, of whom 1.8 million were found alive in camps after the war and 318,770 were released by the Axis during the war and were then drafted into the Soviet armed forces again. By comparison, 8,348 Western Allied prisoners died in German camps during 1939–45 (3.5% of the 232,000 total).

The Germans officially justified their policy on the grounds that the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention. Legally, however, under article 82 of the Geneva Convention, signatory countries had to give POWs of all signatory and non-signatory countries the rights assigned by the convention. Shortly after the German invasion in 1941, the USSR made Berlin an offer of a reciprocal adherence to the Hague Conventions. Third Reich officials left the Soviet "note" unanswered. In contrast, Nikolai Tolstoy recounts that the German Government – as well as the International Red Cross – made several efforts to regulate reciprocal treatment of prisoners until early 1942, but received no answers from the Soviet side. Further, the Soviets took a harsh position towards captured Soviet soldiers, as they expected each soldier to fight to the death, and automatically excluded any prisoner from the "Russian community".

Some Soviet POWs and forced labourers whom the Germans had transported to Nazi Germany were, on their return to the USSR, treated as traitors and sent to gulag prison-camps.

Treatment of POWs by the Soviet Union

Germans, Romanians, Italians, Hungarians, Finns

According to some sources, the Soviets captured 3.5 million Axis servicemen (excluding Japanese), of which more than a million died. One specific example is that of the German POWs after the Battle of Stalingrad, where the Soviets captured 91,000 German troops in total (completely exhausted, starving and sick), of whom only 5,000 survived the captivity.

German soldiers were kept as forced labour for many years after the war. The last German POWs like Erich Hartmann, the highest-scoring fighter ace in the history of aerial warfare, who had been declared guilty of war crimes but without due process, were not released by the Soviets until 1955, two years after Stalin died.

Polish

As a result of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers became prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. Thousands were executed; over 20,000 Polish military personnel and civilians perished in the Katyn massacre. Out of Anders' 80,000 evacuees from the Soviet Union in the United Kingdom, only 310 volunteered to return to Poland in 1947.

Of the 230,000 Polish prisoners of war taken by the Soviet army, only 82,000 survived.

Japanese

After the Soviet–Japanese War, 560,000 to 760,000 Japanese prisoners of war were captured by the Soviet Union. The prisoners were captured in Manchuria, Korea, South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, then sent to work as forced labour in the Soviet Union and Mongolia. An estimated 60,000 to 347,000 of these Japanese prisoners of war died in captivity.

Americans

Stories that circulated during the Cold War claimed 23,000 Americans held in German POW camps had been seized by the Soviets and never been repatriated. The claims had been perpetuated after the release of people like John H. Noble. Careful scholarly studies demonstrated that this was a myth based on the misinterpretation of a telegram about Soviet prisoners held in Italy.

Treatment of POWs by the Western Allies

Germans

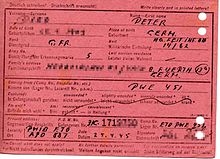

of a German General

(Front- and Backside)

During the war, the armies of Western Allied nations such as Australia, Canada, the UK and the US were given orders to treat Axis prisoners strictly in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Some breaches of the Convention took place, however. According to Stephen E. Ambrose, of the roughly 1,000 US combat veterans he had interviewed, only one admitted to shooting a prisoner, saying he "felt remorse, but would do it again". However, one-third of interviewees told him they had seen fellow US troops kill German prisoners.

In Britain, German prisoners, particularly higher-ranked officers, were housed in luxurious buildings where listening devices were installed. A considerable amount of military intelligence was gained from eavesdropping on what the officers believed were private casual conversations. Much of the listening was carried out by German refugees, in many cases Jews. The work of these refugees in contributing to the Allied victory was declassified over half a century later.

In February 1944, 59.7% of POWs in America were employed. This relatively low percentage was due to problems setting wages that would not compete against those of non-prisoners, to union opposition, as well as concerns about security, sabotage, and escape. Given national manpower shortages, citizens and employers resented the idle prisoners, and efforts were made to decentralize the camps and reduce security enough that more prisoners could work. By the end of May 1944, POW employment was at 72.8%, and by late April 1945 it had risen to 91.3%. The sector that made the most use of POW workers was agriculture. There was more demand than supply of prisoners throughout the war, and 14,000 POW repatriations were delayed in 1946 so prisoners could be used in the spring farming seasons, mostly to thin and block sugar beets in the west. While some in Congress wanted to extend POW labour beyond June 1946, President Truman rejected this, leading to the end of the program.

Towards the end of the war in Europe, as large numbers of Axis soldiers surrendered, the US created the designation of Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF) so as not to treat prisoners as POWs. A lot of these soldiers were kept in open fields in makeshift camps in the Rhine valley (Rheinwiesenlager). Controversy has arisen about how Eisenhower managed these prisoners.

After the surrender of Germany in May 1945, the POW status of the German prisoners was in many cases maintained, and they were for several years used as public labourers in countries such as the UK and France. Many died when forced to clear minefields in countries such as Norway and France. "By September 1945 it was estimated by the French authorities that two thousand prisoners were being maimed and killed each month in accidents".

In 1946, the UK held over 400,000 German POWs, many having been transferred from POW camps in the US and Canada. They were employed as labourers to compensate for the lack of manpower in Britain, as a form of war reparation. A public debate ensued in the U.K. over the treatment of German prisoners of war, with many in Britain comparing the treatment to the POWs to slave labour. In 1947, the Ministry of Agriculture argued against repatriation of working German prisoners, since by then they made up 25 percent of the land workforce, and it wanted to continue having them work in the UK until 1948.

The "London Cage", an MI19 prisoner of war facility in London used during and immediately after the war to interrogate prisoners before sending them to prison camps, was subject to allegations of torture.

After the German surrender, the International Red Cross was prohibited from providing aid, such as food or prisoner visits, to POW camps in Germany. However, after making appeals to the Allies in the autumn of 1945, the Red Cross was allowed to investigate the camps in the British and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as providing relief to the prisoners held there. On 4 February 1946, the Red Cross was also permitted to visit and assist prisoners in the US occupation zone of Germany, although only with very small quantities of food. "During their visits, the delegates observed that German prisoners of war were often detained in appalling conditions. They drew the attention of the authorities to this fact, and gradually succeeded in getting some improvements made".

POWs were also transferred among the Allies, with for example 6,000 German officers transferred from Western Allied camps to the Soviets and subsequently imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, at the time one of the NKVD special camps. Although the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention, the U.S. chose to hand over several hundred thousand German prisoners to the Soviet Union in May 1945 as a "gesture of friendship". U.S. forces also refused to accept the surrender of German troops attempting to surrender to them in Saxony and Bohemia, and handed them over to the Soviet Union instead.

The United States handed over 740,000 German prisoners to France, which was a Geneva Convention signatory but which used them as forced labourers. Newspapers reported that the POWs were being mistreated; Judge Robert H. Jackson, chief US prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials, told US President Harry S Truman in October 1945 that the Allies themselves:

have done or are doing some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for. The French are so violating the Geneva Convention in the treatment of prisoners of war that our command is taking back prisoners sent to them. We are prosecuting plunder and our Allies are practicing it.

Hungarians

Hungarians became POWs of the Western Allies. Some of these were, like the Germans, used as forced labour in France after the cessation of hostilities. After the war, Hungarian POWs were handed over to the Soviets and transported to the Soviet Union for forced labour. Such forced Hungarian labour by the USSR is often referred to as malenkij robot—little work. András Toma, a Hungarian soldier taken prisoner by the Red Army in 1944, was discovered in a Russian psychiatric hospital in 2000. He was likely the last prisoner of war from World War II to be repatriated.

Japanese

Although thousands of Japanese servicemembers were taken prisoner, most fought until they were killed or committed suicide. Of the 22,000 Japanese soldiers present at the beginning of the Battle of Iwo Jima, over 20,000 were killed and only 216 were taken prisoner. Of the 30,000 Japanese troops that defended Saipan, fewer than 1,000 remained alive at battle's end. Japanese prisoners sent to camps fared well; however, some were killed when attempting to surrender or were massacred just after doing so (see Allied war crimes during World War II in the Pacific). In some instances, Japanese prisoners were tortured through a variety of methods. A method of torture used by the Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) included suspending prisoners by the neck in wooden cages until they died. In very rare cases, some were beheaded by sword, and a severed head was once used as a football by Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) soldiers.

After the war, many Japanese POWs were kept on as Japanese Surrendered Personnel until mid-1947 by the Allies. The JSP were used until 1947 for labour purposes, such as road maintenance, recovering corpses for reburial, cleaning, and preparing farmland. Early tasks also included repairing airfields damaged by Allied bombing during the war and maintaining law and order until the arrival of Allied forces in the region.

Italians

In 1943, Italy overthrew Mussolini and became an Allied co-belligerent. This did not change the status of many Italian POWs, retained in Australia, the UK and US due to labour shortages.

After Italy surrendered to the Allies and declared war on Germany, the United States initially made plans to send Italian POWs back to fight Germany. Ultimately though, the government decided instead to loosen POW work requirements prohibiting Italian prisoners from carrying out war-related work. About 34,000 Italian POWs were active in 1944 and 1945 on 66 US military installations, performing support roles such as quartermaster, repair, and engineering work.

Cossacks

On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the USSR. The interpretation of this agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets (Operation Keelhaul) regardless of their wishes. The forced repatriation operations took place in 1945–1947.

Post-World War II

During the Korean War, the North Koreans developed a reputation for severely mistreating prisoners of war (see Treatment of POWs by North Korean and Chinese forces). Their POWs were housed in three camps, according to their potential usefulness to the North Korean army. Peace camps and reform camps were for POWs that were either sympathetic to the cause or who had valued skills that could be useful to the North Korean military; these enemy soldiers were indoctrinated and sometimes conscripted into the North Korean army. While POWs in peace camps were reportedly treated with more consideration, regular prisoners of war were usually treated very poorly.

The 1952 Inter-Camp POW Olympics were held from 15 to 27 November 1952 in Pyuktong, North Korea. The Chinese hoped to gain worldwide publicity, and while some prisoners refused to participate, some 500 POWs of eleven nationalities took part. They came from all the North Korean prison camps and competed in football, baseball, softball, basketball, volleyball, track and field, soccer, gymnastics, and boxing. For the POWs, this was also an opportunity to meet with friends from other camps. The prisoners had their own photographers, announcers, and even reporters, who after each day's competition published a newspaper, the "Olympic Roundup".

At the end of the First Indochina War, of the 11,721 French soldiers taken prisoner after the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and led by the Viet Minh on death marches to distant POW camps, only 3,290 were repatriated four months later.

During the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army took many United States servicemembers as prisoners of war and subjected them to mistreatment and torture. Some American prisoners were held in the prison known to US POWs as the Hanoi Hilton.

Communist Vietnamese held in custody by South Vietnamese and American forces were also tortured and badly treated. After the war, millions of South Vietnamese servicemen and government workers were sent to "re-education" camps, where many perished.

As in previous conflicts, speculation existed, without evidence, that a handful of American pilots captured during the Korean and Vietnam wars were transferred to the Soviet Union and never repatriated.

Regardless of regulations determining treatment of prisoners, violations of their rights continue to be reported. Many cases of POW massacres have been reported in recent times, including 13 October massacre in Lebanon by Syrian forces and June 1990 massacre in Sri Lanka.

Indian intervention in the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971 led to the third Indo-Pakistan war, which ended in Indian victory and over 90,000 Pakistani POWs.

In 1982, during the Falklands War, prisoners were well-treated in general by both sides, with military commanders dispatching enemy prisoners back to their homelands in record time.

In 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, American, British, Italian, and Kuwaiti POWs (mostly crew members of downed aircraft and special forces) were tortured by the Iraqi secret police. An American military doctor, Major Rhonda Cornum, a 37-year-old flight surgeon captured when her Blackhawk UH-60 was shot down, was also subjected to sexual abuse.

During the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Serb paramilitary forces supported by JNA forces killed POWs at Vukovar and Škarbrnja, while Bosnian Serb forces killed POWs at Srebrenica. A large number of surviving Croatian or Bosnian POWs described the conditions in serbian concentration camps as similar to those in Germany in World War 2, including regular beatings, torture and random executions.

In 2001, reports emerged concerning two POWs that India had taken during the Sino-Indian War, Yang Chen and Shih Liang. The two were imprisoned as spies for three years before being interned in a mental asylum in Ranchi, where they spent the following 38 years under a special prisoner status.

The last prisoners of the 1980-1988 Iran–Iraq War were exchanged in 2003.

Numbers of POWs

This section lists nations with the highest number of POWs since the start of World War II and ranked by descending order. These are also the highest numbers in any war since the Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War entered into force on 19 June 1931. The USSR had not signed the Geneva convention.

| Armies | Number of POWs held in captivity | Name of conflict |

|---|---|---|

|

World War II | |

| 5.7 million taken by Germany (about 3 million died in captivity (56–68%))

|

World War II (total) | |

| 1,800,000 taken by Germany | World War II | |

| 675,000 (420,000 taken by Germany; 240,000 taken by the Soviets in 1939; 15,000 taken by Germany in Warsaw in 1944) | World War II | |

| ≈200,000 (135,000 taken in Europe, does not include Pacific or Commonwealth figures) | World War II | |

| ≈175,000 taken by Coalition of the Gulf War | Persian Gulf War | |

|

World War II | |

| ≈130,000 (95,532 taken by Germany) | World War II | |

| 93,000 taken by India. Later released by India in accordance with the Simla Agreement. | Bangladesh Liberation War | |

|

World War II |