From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_education

The

philosophy of education examines the goals, forms, methods, and meaning of

education. The term is used to describe both fundamental

philosophical analysis of these themes and the description or analysis of particular

pedagogical approaches. Considerations of how the profession relates to broader philosophical or sociocultural contexts may be included. The philosophy of education thus overlaps with the field of education and

applied philosophy.

For example, philosophers of education study what constitutes

upbringing and education, the values and norms revealed through

upbringing and educational practices, the limits and legitimization of

education as an academic discipline, and the relation between educational theory and practice.

In universities, the philosophy of education usually forms part of departments or colleges of education.

Philosophy of education

Plato

Date: 424/423 BC – 348/347 BC

Plato's educational philosophy was grounded in a vision of an ideal Republic wherein the individual

was best served by being subordinated to a just society due to a shift

in emphasis that departed from his predecessors. The mind and body were

to be considered separate entities. In the dialogues of Phaedo,

written in his "middle period" (360 B.C.E.) Plato expressed his

distinctive views about the nature of knowledge, reality, and the soul:

When

the soul and body are united, then nature orders the soul to rule and

govern, and the body to obey and serve. Now which of these two functions

is akin to the divine? and which to the mortal? Does not the divine

appear…to be that which naturally orders and rules, and the mortal to be

that which is subject and servant?

On this premise, Plato advocated removing children from their mothers' care and raising them as wards of the state,

with great care being taken to differentiate children suitable to the

various castes, the highest receiving the most education, so that they

could act as guardians of the city and care for the less able. Education

would be holistic, including facts, skills, physical discipline, and music and art, which he considered the highest form of endeavor.

Plato believed that talent was distributed non-genetically and thus must be found in children born in any social class. He built on this by insisting that those suitably gifted were to be trained by the state so that they might be qualified to assume the role of a ruling class. What this established was essentially a system of selective public education

premised on the assumption that an educated minority of the population

were, by virtue of their education (and inborn educability), sufficient

for healthy governance.

Plato's writings contain some of the following ideas:

Elementary education would be confined to the guardian class till the age of 18, followed by two years of compulsory military training and then by higher education

for those who qualified. While elementary education made the soul

responsive to the environment, higher education helped the soul to

search for truth which illuminated it. Both boys and girls receive the

same kind of education. Elementary education consisted of music and

gymnastics, designed to train and blend gentle and fierce qualities in

the individual and create a harmonious person.

At the age of 20, a selection was made. The best students would take an advanced course in mathematics, geometry, astronomy

and harmonics. The first course in the scheme of higher education would

last for ten years. It would be for those who had a flair for science.

At the age of 30 there would be another selection; those who qualified

would study dialectics and metaphysics, logic and philosophy

for the next five years. After accepting junior positions in the army

for 15 years, a man would have completed his theoretical and practical

education by the age of 50.

Immanuel Kant

Date: 1724–1804

Immanuel Kant believed that education differs from training in

that the former involves thinking whereas the latter does not. In

addition to educating reason, of central importance to him was the

development of character and teaching of moral maxims. Kant was a

proponent of public education and of learning by doing.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Date: 1770–1831

Realism

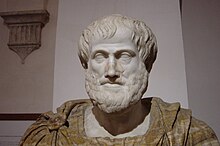

Aristotle

Bust of Aristotle. Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by

Lysippos from 330 B.C.

Date: 384 BC – 322 BC

Only fragments of Aristotle's treatise On Education are

still in existence. We thus know of his philosophy of education

primarily through brief passages in other works. Aristotle considered

human nature, habit and reason to be equally important forces to be cultivated in education.

Thus, for example, he considered repetition to be a key tool to develop

good habits. The teacher was to lead the student systematically; this

differs, for example, from Socrates' emphasis on questioning his

listeners to bring out their own ideas (though the comparison is perhaps

incongruous since Socrates was dealing with adults).

Aristotle placed great emphasis on balancing the theoretical and

practical aspects of subjects taught. Subjects he explicitly mentions as

being important included reading, writing and mathematics; music;

physical education; literature and history; and a wide range of

sciences. He also mentioned the importance of play.

One of education's primary missions for Aristotle, perhaps its most important, was to produce good and virtuous citizens for the polis. All who have meditated on the art of governing mankind have been convinced that the fate of empires depends on the education of youth.

Ibn Sina

Date: 980 AD – 1037 AD

In the medieval Islamic world, an elementary school was known as a maktab, which dates back to at least the 10th century. Like madrasahs (which referred to higher education), a maktab was often attached to a mosque. In the 11th century, Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West), wrote a chapter dealing with the maktab entitled "The Role of the Teacher in the Training and Upbringing of Children", as a guide to teachers working at maktab schools. He wrote that children can learn better if taught in classes instead of individual tuition from private tutors, and he gave a number of reasons for why this is the case, citing the value of competition and emulation among pupils as well as the usefulness of group discussions and debates. Ibn Sina described the curriculum of a maktab school in some detail, describing the curricula for two stages of education in a maktab school.

Ibn Sina wrote that children should be sent to a maktab school from the age of 6 and be taught primary education until they reach the age of 14. During which time, he wrote that they should be taught the Qur'an, Islamic metaphysics, language, literature, Islamic ethics, and manual skills (which could refer to a variety of practical skills).

Ibn Sina refers to the secondary education stage of maktab

schooling as the period of specialization, when pupils should begin to

acquire manual skills, regardless of their social status. He writes that

children after the age of 14 should be given a choice to choose and

specialize in subjects they have an interest in, whether it was reading,

manual skills, literature, preaching, medicine, geometry, trade and commerce, craftsmanship, or any other subject or profession they would be interested in pursuing for a future career.

He wrote that this was a transitional stage and that there needs to be

flexibility regarding the age in which pupils graduate, as the student's

emotional development and chosen subjects need to be taken into

account.

The empiricist theory of 'tabula rasa' was also developed by Ibn Sina. He argued that the "human intellect at birth is rather like a tabula rasa, a pure potentiality that is actualized through education and comes to know" and that knowledge is attained through "empirical familiarity with objects in this world from which one abstracts universal concepts" which is developed through a "syllogistic method of reasoning;

observations lead to prepositional statements, which when compounded

lead to further abstract concepts." He further argued that the intellect

itself "possesses levels of development from the material intellect (al-‘aql al-hayulani), that potentiality that can acquire knowledge to the active intellect (al-‘aql al-fa‘il), the state of the human intellect in conjunction with the perfect source of knowledge."

Ibn Tufail

Date: c. 1105 – 1185

In the 12th century, the Andalusian-Arabian philosopher and novelist Ibn Tufail (known as "Abubacer" or "Ebn Tophail" in the West) demonstrated the empiricist theory of 'tabula rasa' as a thought experiment through his Arabic philosophical novel, Hayy ibn Yaqzan, in which he depicted the development of the mind of a feral child "from a tabula rasa to that of an adult, in complete isolation from society" on a desert island, through experience alone. Some scholars have argued that the Latin translation of his philosophical novel, Philosophus Autodidactus, published by Edward Pococke the Younger in 1671, had an influence on John Locke's formulation of tabula rasa in "An Essay Concerning Human Understanding".

Montaigne

Child education was among the psychological topics that Michel de Montaigne wrote about. His essays On the Education of Children, On Pedantry, and On Experience explain the views he had on child education. Some of his views on child education are still relevant today.

Montaigne's views on the education of children were opposed to the common educational practices of his day. He found fault both with what was taught and how it was taught. Much of the education during Montaigne's time was focused on the reading of the classics and learning through books. Montaigne

disagreed with learning strictly through books. He believed it was

necessary to educate children in a variety of ways. He also disagreed

with the way information was being presented to students. It was being

presented in a way that encouraged students to take the information that

was taught to them as absolute truth. Students were denied the chance

to question the information. Therefore, students could not truly learn.

Montaigne believed that, to learn truly, a student had to take the

information and make it their own.

At the foundation Montaigne believed that the selection of a good tutor was important for the student to become well educated. Education by a tutor was to be conducted at the pace of the student. He

believed that a tutor should be in dialogue with the student, letting

the student speak first. The tutor also should allow for discussions and

debates to be had. Such a dialogue was intended to create an

environment in which students would teach themselves. They would be able

to realize their mistakes and make corrections to them as necessary.

Individualized learning was integral to his theory of child

education. He argued that the student combines information already known

with what is learned and forms a unique perspective on the newly

learned information. Montaigne also thought that tutors should encourage the natural curiosity of students and allow them to question things. He

postulated that successful students were those who were encouraged to

question new information and study it for themselves, rather than simply

accepting what they had heard from the authorities on any given topic.

Montaigne believed that a child's curiosity could serve as an important

teaching tool when the child is allowed to explore the things that the

child is curious about.

Experience also was a key element to learning for Montaigne.

Tutors needed to teach students through experience rather than through

the mere memorization of information often practised in book learning. He argued that students would become passive adults, blindly obeying and lacking the ability to think on their own. Nothing of importance would be retained and no abilities would be learned. He believed that learning through experience was superior to learning through the use of books.

For this reason he encouraged tutors to educate their students through

practice, travel, and human interaction. In doing so, he argued that

students would become active learners, who could claim knowledge for

themselves.

Montaigne's views on child education continue to have an

influence in the present. Variations of Montaigne's ideas on education

are incorporated into modern learning in some ways. He argued against

the popular way of teaching in his day, encouraging individualized

learning. He believed in the importance of experience, over book

learning and memorization. Ultimately, Montaigne postulated that the

point of education was to teach a student how to have a successful life

by practicing an active and socially interactive lifestyle.

John Locke

Date: 1632–1704

In Some Thoughts Concerning Education and Of the Conduct of the Understanding Locke composed an outline on how to educate this mind in order to increase its powers and activity:

"The business of education is not, as I think, to make

them perfect in any one of the sciences, but so to open and dispose

their minds as may best make them capable of any, when they shall apply

themselves to it."

"If men are for a long time accustomed only to one sort

or method of thoughts, their minds grow stiff in it, and do not readily

turn to another. It is therefore to give them this freedom, that I think

they should be made to look into all sorts of knowledge, and exercise

their understandings in so wide a variety and stock of knowledge. But I

do not propose it as a variety and stock of knowledge, but a variety and

freedom of thinking, as an increase of the powers and activity of the

mind, not as an enlargement of its possessions."

Locke expressed the belief that education maketh the man, or, more

fundamentally, that the mind is an "empty cabinet", with the statement,

"I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten

are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education."

Locke also wrote that "the little and almost insensible

impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting

consequences." He argued that the "associations of ideas"

that one makes when young are more important than those made later

because they are the foundation of the self: they are, put differently,

what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which is

introduced both of these concepts, Locke warns against, for example,

letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are

associated with the night for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring

with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can

no more bear the one than the other."

"Associationism", as this theory would come to be called, exerted

a powerful influence over eighteenth-century thought, particularly educational theory,

as nearly every educational writer warned parents not to allow their

children to develop negative associations. It also led to the

development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley's attempt to discover a biological mechanism for associationism in his Observations on Man (1749).

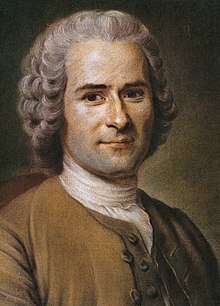

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Date: 1712–1778

Rousseau, though he paid his respects to Plato's philosophy, rejected it as impractical due to the decayed state of society.

Rousseau also had a different theory of human development; where Plato

held that people are born with skills appropriate to different castes

(though he did not regard these skills as being inherited), Rousseau

held that there was one developmental process common to all humans. This

was an intrinsic, natural process, of which the primary behavioral

manifestation was curiosity. This differed from Locke's 'tabula rasa'

in that it was an active process deriving from the child's nature,

which drove the child to learn and adapt to its surroundings.

Rousseau wrote in his book Emile

that all children are perfectly designed organisms, ready to learn from

their surroundings so as to grow into virtuous adults, but due to the

malign influence of corrupt society, they often fail to do so.

Rousseau advocated an educational method which consisted of removing

the child from society—for example, to a country home—and alternately

conditioning him through changes to his environment and setting traps

and puzzles for him to solve or overcome.

Rousseau was unusual in that he recognized and addressed the potential of a problem of legitimation for teaching.

He advocated that adults always be truthful with children, and in

particular that they never hide the fact that the basis for their

authority in teaching was purely one of physical coercion: "I'm bigger

than you." Once children reached the age of reason, at about 12, they

would be engaged as free individuals in the ongoing process of their

own.

He once said that a child should grow up without adult

interference and that the child must be guided to suffer from the

experience of the natural consequences of his own acts or behaviour.

When he experiences the consequences of his own acts, he advises

himself.

"Rousseau divides development into five stages (a book is devoted

to each). Education in the first two stages seeks to the senses: only

when Émile is about 12 does the tutor begin to work to develop his mind.

Later, in Book 5, Rousseau examines the education of Sophie (whom Émile

is to marry).

Here he sets out what he sees as the essential differences that flow

from sex. 'The man should be strong and active; the woman should be weak

and passive' (Everyman edn: 322). From this difference comes a

contrasting education. They are not to be brought up in ignorance and

kept to housework: Nature means them to think, to will, to love to

cultivate their minds as well as their persons; she puts these weapons

in their hands to make up for their lack of strength and to enable them

to direct the strength of men. They should learn many things, but only

such things as suitable' (Everyman edn.: 327)."

Émile

Mortimer Jerome Adler

Date: 1902–2001

Mortimer Jerome Adler was an American philosopher, educator, and popular author. As a philosopher he worked within the Aristotelian and Thomistic traditions. He lived for the longest stretches in New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, and San Mateo, California. He worked for Columbia University, the University of Chicago, Encyclopædia Britannica, and Adler's own Institute for Philosophical Research. Adler was married twice and had four children. Adler was a proponent of educational perennialism.

Harry S. Broudy

Date: 1905–1998

Broudy's philosophical views were based on the tradition of

classical realism, dealing with truth, goodness, and beauty. However he

was also influenced by the modern philosophy existentialism and

instrumentalism. In his textbook Building a Philosophy of Education he

has two major ideas that are the main points to his philosophical

outlook: The first is truth and the second is universal structures to be

found in humanity's struggle for education and the good life. Broudy

also studied issues on society's demands on school. He thought education

would be a link to unify the diverse society and urged the society to

put more trust and a commitment to the schools and a good education.

Scholasticism

Thomas Aquinas

Date: c. 1225 – 1274

See Religious perennialism.

John Milton

Date: 1608–1674

The objective of medieval education was an overtly religious one,

primarily concerned with uncovering transcendental truths that would

lead a person back to God through a life of moral and religious choice

(Kreeft 15). The vehicle by which these truths were uncovered was

dialectic:

To the medieval mind, debate was a fine art, a serious science,

and a fascinating entertainment, much more than it is to the modern

mind, because the medievals believed, like Socrates, that dialectic

could uncover truth. Thus a 'scholastic disputation' was not a personal

contest in cleverness, nor was it 'sharing opinions'; it was a shared

journey of discovery (Kreeft 14–15).

Pragmatism

John Dewey

Date: 1859–1952

In Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education,

Dewey stated that education, in its broadest sense, is the means of the

"social continuity of life" given the "primary ineluctable facts of the

birth and death of each one of the constituent members in a social

group". Education is therefore a necessity, for "the life of the group

goes on." Dewey was a proponent of Educational Progressivism and was a relentless campaigner for reform of education, pointing out that the authoritarian,

strict, pre-ordained knowledge approach of modern traditional education

was too concerned with delivering knowledge, and not enough with

understanding students' actual experiences.

William James

Date: 1842–1910

William Heard Kilpatrick

Date: 1871–1965

William Heard Kilpatrick was a US American philosopher of education and a colleague and a successor of John Dewey. He was a major figure in the progressive education movement of the early 20th century. Kilpatrick developed the Project Method for early childhood education, which was a form of Progressive Education

organized curriculum and classroom activities around a subject's

central theme. He believed that the role of a teacher should be that of a

"guide" as opposed to an authoritarian figure. Kilpatrick believed that

children should direct their own learning according to their interests

and should be allowed to explore their environment, experiencing their

learning through the natural senses.

Proponents of Progressive Education and the Project Method reject

traditional schooling that focuses on memorization, rote learning,

strictly organized classrooms (desks in rows; students always seated),

and typical forms of assessment.

Nel Noddings

Date: 1929–

Noddings' first sole-authored book Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education (1984) followed close on the 1982 publication of Carol Gilligan’s ground-breaking work in the ethics of care In a Different Voice. While her work on ethics continued, with the publication of Women and Evil (1989) and later works on moral education, most of her later publications have been on the philosophy of education and educational theory. Her most significant works in these areas have been Educating for Intelligent Belief or Unbelief (1993) and Philosophy of Education (1995).

Noddings' contribution to education philosophy centers around the ethic of care.

Her belief was that a caring teacher-student relationship will result

in the teacher designing a differentiated curriculum for each student,

and that this curriculum would be based around the students' particular

interests and needs. The teacher's claim to care must not be based on a

one time virtuous decision but an ongoing interest in the students'

welfare.

Richard Rorty

Date: 1931–2007

Analytic philosophy

G.E Moore (1873–1958)

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970)

Gottlob Frege (1848–1925)

Richard Stanley Peters (1919–2011)

Date: 1919–

Existentialist

The

existentialist sees the world as one's personal subjectivity, where

goodness, truth, and reality are individually defined. Reality is a

world of existing, truth subjectively chosen, and goodness a matter of

freedom. The subject matter of existentialist classrooms should be a

matter of personal choice. Teachers view the individual as an entity

within a social context in which the learner must confront others' views

to clarify his or her own. Character development emphasizes individual

responsibility for decisions. Real answers come from within the

individual, not from outside authority. Examining life through authentic

thinking involves students in genuine learning experiences.

Existentialists are opposed to thinking about students as objects to be

measured, tracked, or standardized. Such educators want the educational

experience to focus on creating opportunities for self-direction and

self-actualization. They start with the student, rather than on

curriculum content.

Critical theory

Paulo Freire

Date: 1921–1997

A Brazilian philosopher and educator committed to the cause of educating the impoverished peasants of his nation and collaborating

with them in the pursuit of their liberation from what he regarded as

"oppression," Freire is best known for his attack on what he called the

"banking concept of education," in which the student was viewed as an

empty account to be filled by the teacher. Freire also suggests that a

deep reciprocity be inserted into our notions of teacher and student; he

comes close to suggesting that the teacher-student dichotomy be

completely abolished, instead promoting the roles of the participants in

the classroom as the teacher-student (a teacher who learns) and the

student-teacher (a learner who teaches). In its early, strong form this

kind of classroom has sometimes been criticized on the grounds that it can mask rather than overcome the teacher's authority.

Aspects of the Freirian philosophy have been highly influential

in academic debates over "participatory development" and development

more generally. Freire's emphasis on what he describes as "emancipation"

through interactive participation has been used as a rationale for the

participatory focus of development, as it is held that 'participation'

in any form can lead to empowerment of poor or marginalised groups.

Freire was a proponent of critical pedagogy.

"He participated in the import of European doctrines and ideas into Brazil,

assimilated them to the needs of a specific socio-economic situation, and thus expanded and

refocused them in a thought-provoking way"

Other Continental thinkers

Martin Heidegger

Date: 1889–1976

Heidegger's philosophizing about education was primarily related

to higher education. He believed that teaching and research in the

university should be unified and aim towards testing and interrogating

the "ontological assumptions presuppositions which implicitly guide

research in each domain of knowledge."

Hans-Georg Gadamer

Date: 1900–2002

Jean-François Lyotard

Date: 1924–1998

Michel Foucault

Date: 1926–1984

Michel Foucault understood education as an inherently political

act involving power relationships. He called upon his readers to

transform modern education in the direction of egalitarian

relationships.

Normative educational philosophies

"Normative

philosophies or theories of education may make use of the results of

philosophical thought and of factual inquiries about human beings and

the psychology of learning, but in any case they propound views about

what education should be, what dispositions it should cultivate, why it

ought to cultivate them, how and in whom it should do so, and what forms

it should take. In a full-fledged philosophical normative theory of

education, besides analysis of the sorts described, there will normally

be propositions of the following kinds:

- Basic normative premises about what is good or right;

- Basic factual premises about humanity and the world;

- Conclusions, based on these two kinds of premises, about the dispositions education should foster;

- Further factual premises about such things as the psychology of learning and methods of teaching; and

- Further conclusions about such things as the methods that education should use."

Perennialism

Perennialists believe that one should teach the things that one deems

to be of everlasting importance to all people everywhere. They believe

that the most important topics develop a person. Since details of fact

change constantly, these cannot be the most important. Therefore, one

should teach principles, not facts. Since people are human, one should

teach first about humans, not machines or techniques. Since people are

people first, and workers second if at all, one should teach liberal

topics first, not vocational topics. The focus is primarily on teaching

reasoning and wisdom rather than facts, the liberal arts rather than

vocational training.

Allan Bloom

Date: 1930–1992

Bloom, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, argued for a traditional Great Books-based liberal education in his lengthy essay The Closing of the American Mind.

Classical education

The Classical education movement advocates a form of education based

in the traditions of Western culture, with a particular focus on

education as understood and taught in the Middle Ages. The term

"classical education" has been used in English for several centuries,

with each era modifying the definition and adding its own selection of

topics. By the end of the 18th century, in addition to the trivium and

quadrivium of the Middle Ages, the definition of a classical education

embraced study of literature, poetry, drama, philosophy, history, art,

and languages. In the 20th and 21st centuries it is used to refer to a

broad-based study of the liberal arts and sciences, as opposed to a

practical or pre-professional program. Classical Education can be

described as rigorous and systematic, separating children and their

learning into three rigid categories, Grammar, Dialectic, and Rhetoric.

Charlotte Mason

Date: 1842–1923

Mason was a British educator who invested her life in improving

the quality of children's education. Her ideas led to a method used by

some homeschoolers. Mason's philosophy of education is probably best

summarized by the principles given at the beginning of each of her

books. Two key mottos taken from those principles are "Education is an

atmosphere, a discipline, a life" and "Education is the science of

relations." She believed that children were born persons and should be

respected as such; they should also be taught the Way of the Will and

the Way of Reason. Her motto for students was "I am, I can, I ought, I

will." Charlotte Mason believed that children should be introduced to

subjects through living books, not through the use of "compendiums,

abstracts, or selections." She used abridged books only when the content

was deemed inappropriate for children. She preferred that parents or

teachers read aloud those texts (such as Plutarch and the Old

Testament), making omissions only where necessary.

Essentialism

Educational essentialism is an educational philosophy whose adherents

believe that children should learn the traditional basic subjects and

that these should be learned thoroughly and rigorously. This is based on

the view that there are essentials that men should know for being

educated and are expected to learn the academic areas of reading,

writing, mathematics, science, geography, and technology.

This movement, thus, stresses the role played by the teacher as the

authority in the classroom, driving the goal of content mastery.

An essentialist program normally teaches children progressively, from less complex skills to more complex. The "back to basics" movement is an example of essentialism.

William Chandler Bagley

Date: 1874–1946

William Chandler Bagley taught in elementary schools before

becoming a professor of education at the University of Illinois, where

he served as the Director of the School of Education from 1908 until

1917. He was a professor of education at Teachers College, Columbia,

from 1917 to 1940. An opponent of pragmatism and progressive education,

Bagley insisted on the value of knowledge for its own sake, not merely

as an instrument, and he criticized his colleagues for their failure to

emphasize systematic study of academic subjects. Bagley was a proponent

of educational essentialism.

Social reconstructionism and critical pedagogy

Critical pedagogy is an "educational movement, guided by passion and principle, to help students develop consciousness

of freedom, recognize authoritarian tendencies, and connect knowledge

to power and the ability to take constructive action." Based in Marxist theory, critical pedagogy draws on radical democracy, anarchism, feminism, and other movements for social justice.

George Counts

Date: 1889–1974

Maria Montessori

Date: 1870–1952

The Montessori method arose from Dr. Maria Montessori's discovery

of what she referred to as "the child's true normal nature" in 1907,

which happened in the process of her experimental observation of young

children given freedom in an environment prepared with materials

designed for their self-directed learning activity.

The method itself aims to duplicate this experimental observation of

children to bring about, sustain and support their true natural way of

being.

Rudolf Steiner (Waldorf education)

Date: 1861–1925

Waldorf education (also known as Steiner or Steiner-Waldorf

education) is a humanistic approach to pedagogy based upon the

educational philosophy of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Now known as Waldorf or Steiner education, his pedagogy emphasizes a balanced development of cognitive, affective/artistic,

and practical skills (head, heart, and hands). Schools are normally

self-administered by faculty; emphasis is placed upon giving individual

teachers the freedom to develop creative methods.

Steiner's theory of child development divides education into

three discrete developmental stages predating but with close

similarities to the stages of development described by Piaget.

Early childhood education occurs through imitation; teachers provide

practical activities and a healthy environment. Steiner believed that

young children should meet only goodness. Elementary education is

strongly arts-based, centered on the teacher's creative authority; the

elementary school-age child should meet beauty. Secondary education

seeks to develop the judgment, intellect, and practical idealism; the

adolescent should meet truth.

Learning is interdisciplinary, integrating practical, artistic,

and conceptual elements. The approach emphasizes the role of the

imagination in learning, developing thinking that includes a creative as

well as an analytic component. The educational philosophy's overarching

goals are to provide young people the basis on which to develop into

free, morally responsible and integrated individuals, and to help every

child fulfill his or her unique destiny, the existence of which

anthroposophy posits. Schools and teachers are given considerable

freedom to define curricula within collegial structures.

Democratic education

Democratic education is a theory of learning and school governance in

which students and staff participate freely and equally in a school

democracy. In a democratic school, there is typically shared

decision-making among students and staff on matters concerning living,

working, and learning together.

A. S. Neill

Date: 1883–1973

Neill founded Summerhill School, the oldest existing democratic school

in Suffolk, England in 1921. He wrote a number of books that now define

much of contemporary democratic education philosophy. Neill believed

that the happiness of the child should be the paramount consideration in

decisions about the child's upbringing, and that this happiness grew

from a sense of personal freedom. He felt that deprivation of this sense

of freedom during childhood, and the consequent unhappiness experienced

by the repressed child, was responsible for many of the psychological

disorders of adulthood.

Progressivism

Educational progressivism is the belief that education must be based on the principle that humans are social animals who learn best in real-life activities with other people. Progressivists,

like proponents of most educational theories, claim to rely on the best

available scientific theories of learning. Most progressive educators

believe that children learn as if they were scientists, following a

process similar to John Dewey's model of learning known as "the pattern

of inquiry":

1) Become aware of the problem. 2) Define the problem. 3) Propose

hypotheses to solve it. 4) Evaluate the consequences of the hypotheses

from one's past experience. 5) Test the likeliest solution.

John Dewey

Date: 1859–1952

In 1896, Dewey opened the Laboratory School at the University of

Chicago in an institutional effort to pursue together rather than apart

"utility and culture, absorption and expression, theory and practice,

[which] are [indispensable] elements in any educational scheme.

As the unified head of the departments of Philosophy, Psychology and

Pedagogy, John Dewey articulated a desire to organize an educational

experience where children could be more creative than the best of

progressive models of his day. Transactionalism

as a pragmatic philosophy grew out of the work he did in the Laboratory

School. The two most influential works that stemmed from his research

and study were The Child and the Curriculum (1902) and Democracy and Education (1916).

Dewey wrote of the dualisms that plagued educational philosophy in the

latter book: "Instead of seeing the educative process steadily and as a

whole, we see conflicting terms. We get the case of the child vs. the

curriculum; of the individual nature vs. social culture."

Dewey found that the preoccupation with facts as knowledge in the

educative process led students to memorize "ill-understood rules and

principles" and while second-hand knowledge learned in mere words is a

beginning in study, mere words can never replace the ability to organize

knowledge into both useful and valuable experience.

Jean Piaget

Date: 1896–1980

Jean Piaget was a Swiss developmental psychologist known for his epistemological studies with children. His theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called "genetic epistemology".

Piaget placed great importance on the education of children. As the

Director of the International Bureau of Education, he declared in 1934

that "only education is capable of saving our societies from possible

collapse, whether violent, or gradual." Piaget created the International Centre for Genetic Epistemology in Geneva in 1955 and directed it until 1980. According to Ernst von Glasersfeld, Jean Piaget is "the great pioneer of the constructivist theory of knowing."

Jean Piaget described himself as an epistemologist,

interested in the process of the qualitative development of knowledge.

As he says in the introduction of his book "Genetic Epistemology" (ISBN 978-0-393-00596-7): "What

the genetic epistemology proposes is discovering the roots of the

different varieties of knowledge, since its elementary forms, following

to the next levels, including also the scientific knowledge."

Jerome Bruner

Date: 1915–2016

Another important contributor to the inquiry method in education is Bruner. His books The Process of Education and Toward a Theory of Instruction

are landmarks in conceptualizing learning and curriculum development.

He argued that any subject can be taught in some intellectually honest

form to any child at any stage of development. This notion was an

underpinning for his concept of the "spiral" (helical)

curriculum which posited the idea that a curriculum should revisit

basic ideas, building on them until the student had grasped the full

formal concept. He emphasized intuition as a neglected but essential

feature of productive thinking. He felt that interest in the material

being learned was the best stimulus for learning rather than external

motivation such as grades. Bruner developed the concept of discovery learning

which promoted learning as a process of constructing new ideas based on

current or past knowledge. Students are encouraged to discover facts

and relationships and continually build on what they already know.

Unschooling

Unschooling is a range of educational philosophies and practices centered on allowing children to learn through their natural life experiences, including child directed play, game play, household responsibilities, work experience, and social interaction,

rather than through a more traditional school curriculum. Unschooling

encourages exploration of activities led by the children themselves,

facilitated by the adults. Unschooling differs from conventional

schooling principally in the thesis that standard curricula and conventional grading

methods, as well as other features of traditional schooling, are

counterproductive to the goal of maximizing the education of each child.

John Holt

In 1964 Holt published his first book, How Children Fail, asserting that the academic failure of schoolchildren was not despite the efforts of the schools, but actually because of the schools. Not surprisingly, How Children Fail

ignited a firestorm of controversy. Holt was catapulted into the

American national consciousness to the extent that he made appearances

on major TV talk shows, wrote book reviews for Life magazine, and was a guest on the To Tell The Truth TV game show. In his follow-up work, How Children Learn,

published in 1967, Holt tried to elucidate the learning process of

children and why he believed school short circuits that process.

Contemplative education

Contemplative education

focuses on bringing introspective practices such as mindfulness and

yoga into curricular and pedagogical processes for diverse aims grounded

in secular, spiritual, religious and post-secular perspectives.

Contemplative approaches may be used in the classroom, especially in

tertiary or (often in modified form) in secondary education. Parker Palmer is a recent pioneer in contemplative methods. The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society founded a branch focusing on education, The Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education.

Contemplative methods may also be used by teachers in their preparation; Waldorf education

was one of the pioneers of the latter approach. In this case,

inspiration for enriching the content, format, or teaching methods may

be sought through various practices, such as consciously reviewing the

previous day's activities; actively holding the students in

consciousness; and contemplating inspiring pedagogical texts. Zigler

suggested that only through focusing on their own spiritual development

could teachers positively impact the spiritual development of students.