| Bitcoin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Denominations | |

| Plural | Bitcoins |

| Symbol | ₿ (Unicode: U+20BF ₿ BITCOIN SIGN (HTML ₿))[a] |

| Code | BTC, XBT[b] |

| Precision | 10−8 |

| Subunits | |

| 1⁄1000 | Millibitcoin |

| 1⁄1000000 | Microbitcoin |

| 1⁄100000000 | Satoshi[2] |

| Development | |

| Original author(s) | Satoshi Nakamoto |

| White paper | "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" |

| Implementation(s) | Bitcoin Core |

| Initial release | 0.1.0 / 9 January 2009 |

| Latest release | 22.0 / 13 September 2021 |

| Code repository | github |

| Development status | Active |

| Website | bitcoin |

| Ledger | |

| Ledger start | 3 January 2009 |

| Timestamping scheme | Proof-of-work (partial hash inversion) |

| Hash function | SHA-256 (two rounds) |

| Issuance schedule | Decentralized (block reward) Initially ₿50 per block, halved every 210,000 blocks |

| Block reward | ₿6.25[c] |

| Block time | 10 minutes |

| Circulating supply | ₿18,830,000[d] |

| Supply limit | ₿21,000,000[e] |

| Valuation | |

| Exchange rate | Floating (very volatile) |

| Market cap | US$811 billion[f] |

| Demographics | |

| Official user(s) | |

|

Bitcoin (₿) is a decentralized digital currency, without a central bank or single administrator, that can be sent from user to user on the peer-to-peer bitcoin network without the need for intermediaries. Transactions are verified by network nodes through cryptography and recorded in a public distributed ledger called a blockchain. The cryptocurrency was invented in 2008 by an unknown person or group of people using the name Satoshi Nakamoto. The currency began use in 2009 when its implementation was released as open-source software.

Bitcoins are created as a reward for a process known as mining. They can be exchanged for other currencies, products, and services, but the real-world value of the coins is extremely volatile. Research produced by the University of Cambridge estimated that in 2017, there were 2.9 to 5.8 million unique users using a cryptocurrency wallet, most of them using bitcoin.

Bitcoin has been criticized for its use in illegal transactions, the large amount of electricity (and thus carbon footprint) used by mining, price volatility, and thefts from exchanges. Some economists and commentators have characterized it as a speculative bubble at various times. Bitcoin has also been used as an investment, although several regulatory agencies have issued investor alerts about bitcoin. In September 2021, El Salvador officially adopted Bitcoin as legal tender, becoming the first and only nation in the world to do so.

The word bitcoin was defined in a white paper published on 31 October 2008. It is a compound of the words bit and coin. No uniform convention for bitcoin capitalization exists; some sources use Bitcoin, capitalized, to refer to the technology and network and bitcoin, lowercase, for the unit of account. The Wall Street Journal, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and the Oxford English Dictionary advocate the use of lowercase bitcoin in all cases.

Design

Units and divisibility

The unit of account of the bitcoin system is a bitcoin. Currency codes used to represent bitcoin are BTC[a] and XBT.[b] Its Unicode character is ₿. Bitcoins are divisible to eight decimal places. Small amounts of bitcoin used as alternative units are millibitcoin (mBTC), and satoshi (sat). Named in homage to bitcoin's creator, a satoshi is the smallest bitcoin unit in the ledger, representing 1⁄100000000 bitcoins; one hundred millionth of a bitcoin. A millibitcoin equals 1⁄1000 bitcoins; one thousandth of a bitcoin or 100,000 satoshis.

Blockchain

The bitcoin blockchain is a public ledger that records bitcoin transactions. It is implemented as a chain of blocks, each block containing a hash of the previous block up to the genesis block[c] of the chain. A network of communicating nodes running bitcoin software maintains the blockchain. Transactions of the form payer X sends Y bitcoins to payee Z are broadcast to this network using readily available software applications.

Network nodes can validate transactions, add them to their copy of the ledger, and then broadcast these ledger additions to other nodes. To achieve independent verification of the chain of ownership each network node stores its own copy of the blockchain. At varying intervals of time averaging to every 10 minutes, a new group of accepted transactions, called a block, is created, added to the blockchain, and quickly published to all nodes, without requiring central oversight. This allows bitcoin software to determine when a particular bitcoin was spent, which is needed to prevent double-spending. A conventional ledger records the transfers of actual bills or promissory notes that exist apart from it, but the blockchain is the only place that bitcoins can be said to exist in the form of unspent outputs of transactions.

Individual blocks, public addresses and transactions within blocks can be examined using a blockchain explorer.

Transactions

Transactions are defined using a Forth-like scripting language. Transactions consist of one or more inputs and one or more outputs. When a user sends bitcoins, the user designates each address and the amount of bitcoin being sent to that address in an output. To prevent double spending, each input must refer to a previous unspent output in the blockchain. The use of multiple inputs corresponds to the use of multiple coins in a cash transaction. Since transactions can have multiple outputs, users can send bitcoins to multiple recipients in one transaction. As in a cash transaction, the sum of inputs (coins used to pay) can exceed the intended sum of payments. In such a case, an additional output is used, returning the change back to the payer. Any input satoshis not accounted for in the transaction outputs become the transaction fee.

Though transaction fees are optional, miners can choose which transactions to process and prioritize those that pay higher fees. Miners may choose transactions based on the fee paid relative to their storage size, not the absolute amount of money paid as a fee. These fees are generally measured in satoshis per byte (sat/b). The size of transactions is dependent on the number of inputs used to create the transaction, and the number of outputs.

The blocks in the blockchain were originally limited to 32 megabytes in size. The block size limit of one megabyte was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2010. Eventually the block size limit of one megabyte created problems for transaction processing, such as increasing transaction fees and delayed processing of transactions. Andreas Antonopoulos has stated Lightning Network is a potential scaling solution and referred to lightning as a second layer routing network.

Ownership

In the blockchain, bitcoins are registered to bitcoin addresses. Creating a bitcoin address requires nothing more than picking a random valid private key and computing the corresponding bitcoin address. This computation can be done in a split second. But the reverse, computing the private key of a given bitcoin address, is practically unfeasible. Users can tell others or make public a bitcoin address without compromising its corresponding private key. Moreover, the number of valid private keys is so vast that it is extremely unlikely someone will compute a key-pair that is already in use and has funds. The vast number of valid private keys makes it unfeasible that brute force could be used to compromise a private key. To be able to spend their bitcoins, the owner must know the corresponding private key and digitally sign the transaction. The network verifies the signature using the public key; the private key is never revealed.

If the private key is lost, the bitcoin network will not recognize any other evidence of ownership; the coins are then unusable, and effectively lost. For example, in 2013 one user claimed to have lost 7,500 bitcoins, worth $7.5 million at the time, when he accidentally discarded a hard drive containing his private key. About 20% of all bitcoins are believed to be lost -they would have had a market value of about $20 billion at July 2018 prices.

To ensure the security of bitcoins, the private key must be kept secret. If the private key is revealed to a third party, e.g. through a data breach, the third party can use it to steal any associated bitcoins. As of December 2017, around 980,000 bitcoins have been stolen from cryptocurrency exchanges.

Regarding ownership distribution, as of 16 March 2018, 0.5% of bitcoin wallets own 87% of all bitcoins ever mined.

Mining

Mining is a record-keeping service done through the use of computer processing power.[f] Miners keep the blockchain consistent, complete, and unalterable by repeatedly grouping newly broadcast transactions into a block, which is then broadcast to the network and verified by recipient nodes. Each block contains a SHA-256 cryptographic hash of the previous block, thus linking it to the previous block and giving the blockchain its name.

To be accepted by the rest of the network, a new block must contain a proof-of-work (PoW). The system used is based on Adam Back's 1997 anti-spam scheme, Hashcash. The PoW requires miners to find a number called a nonce (number used once), such that when the block content is hashed along with the nonce, the result is numerically smaller than the network's difficulty target. This proof is easy for any node in the network to verify, but extremely time-consuming to generate, as for a secure cryptographic hash, miners must try many different nonce values (usually the sequence of tested values is the ascending natural numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, ...) before a result happens to be less than the difficulty target. Because the difficulty target is extremely small compared to a typical SHA-256 hash, block hashes have many leading zeros as can be seen in this example block hash:

0000000000000000000590fc0f3eba193a278534220b2b37e9849e1a770ca959

By adjusting this difficulty target, the amount of work needed to generate a block can be changed. Every 2,016 blocks (approximately 14 days given roughly 10 minutes per block), nodes deterministically adjust the difficulty target based on the recent rate of block generation, with the aim of keeping the average time between new blocks at ten minutes. In this way the system automatically adapts to the total amount of mining power on the network. As of September 2021, it takes on average 79 sextillion (79 thousand billion billion) attempts to generate a block hash smaller than the difficulty target.

The proof-of-work system, alongside the chaining of blocks, makes modifications of the blockchain extremely hard, as an attacker must modify all subsequent blocks in order for the modifications of one block to be accepted. As new blocks are mined all the time, the difficulty of modifying a block increases as time passes and the number of subsequent blocks (also called confirmations of the given block) increases.

Computing power is often bundled together by a Mining pool to reduce variance in miner income. Individual mining rigs often have to wait for long periods to confirm a block of transactions and receive payment. In a pool, all participating miners get paid every time a participating server solves a block. This payment depends on the amount of work an individual miner contributed to help find that block.

Supply

The successful miner finding the new block is allowed by the rest of the network to collect for themselves all transaction fees from transactions they included in the block, as well as a pre-determined reward of newly created bitcoins. As of 11 May 2020, this reward is currently 6.25 newly created bitcoins per block. To claim this reward, a special transaction called a coinbase is included in the block, with the miner as the payee. All bitcoins in existence have been created through this type of transaction. The bitcoin protocol specifies that the reward for adding a block will be reduced by half every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years). Eventually, the reward will round down to zero, and the limit of 21 million bitcoins[g] will be reached c. 2140; the record keeping will then be rewarded by transaction fees only.

Decentralization

Bitcoin is decentralized thus:

- Bitcoin does not have a central authority.

- There is no central server; the bitcoin network is peer-to-peer.

- There is no central storage; the bitcoin ledger is distributed.

- The ledger is public; anybody can store it on their computer.

- There is no single administrator; the ledger is maintained by a network of equally privileged miners.

- Anybody can become a miner.

- The additions to the ledger are maintained through competition. Until a new block is added to the ledger, it is not known which miner will create the block.

- The issuance of bitcoins is decentralized. They are issued as a reward for the creation of a new block.

- Anybody can create a new bitcoin address (a bitcoin counterpart of a bank account) without needing any approval.

- Anybody can send a transaction to the network without needing any approval; the network merely confirms that the transaction is legitimate.

Conversely, researchers have pointed out at a "trend towards centralization". Although bitcoin can be sent directly from user to user, in practice intermediaries are widely used. Bitcoin miners join large mining pools to minimize the variance of their income. Because transactions on the network are confirmed by miners, decentralization of the network requires that no single miner or mining pool obtains 51% of the hashing power, which would allow them to double-spend coins, prevent certain transactions from being verified and prevent other miners from earning income. As of 2013 just six mining pools controlled 75% of overall bitcoin hashing power. In 2014 mining pool Ghash.io obtained 51% hashing power which raised significant controversies about the safety of the network. The pool has voluntarily capped their hashing power at 39.99% and requested other pools to act responsibly for the benefit of the whole network. Around the year 2017, over 70% of the hashing power and 90% of transactions were operating from China.

According to researchers, other parts of the ecosystem are also "controlled by a small set of entities", notably the maintenance of the client software, online wallets and simplified payment verification (SPV) clients.

Privacy and fungibility

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the blockchain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through "idioms of use" (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses. Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information. To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction.

Wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins as equivalent, establishing the basic level of fungibility. Researchers have pointed out that the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the blockchain ledger, and that some users may refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions, which would harm bitcoin's fungibility. For example, in 2012, Mt. Gox froze accounts of users who deposited bitcoins that were known to have just been stolen.

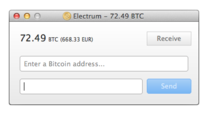

Wallets

A wallet stores the information necessary to transact bitcoins. While wallets are often described as a place to hold or store bitcoins, due to the nature of the system, bitcoins are inseparable from the blockchain transaction ledger. A wallet is more correctly defined as something that "stores the digital credentials for your bitcoin holdings" and allows one to access (and spend) them. Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography, in which two cryptographic keys, one public and one private, are generated. At its most basic, a wallet is a collection of these keys.

Software wallets

The first wallet program, simply named Bitcoin, and sometimes referred to as the Satoshi client, was released in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto as open-source software. In version 0.5 the client moved from the wxWidgets user interface toolkit to Qt, and the whole bundle was referred to as Bitcoin-Qt. After the release of version 0.9, the software bundle was renamed Bitcoin Core to distinguish itself from the underlying network. Bitcoin Core is, perhaps, the best known implementation or client. Alternative clients (forks of Bitcoin Core) exist, such as Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Unlimited, and Parity Bitcoin.

There are several modes which wallets can operate in. They have an inverse relationship with regards to trustlessness and computational requirements.

- Full clients verify transactions directly by downloading a full copy of the blockchain (over 150 GB as of January 2018). They are the most secure and reliable way of using the network, as trust in external parties is not required. Full clients check the validity of mined blocks, preventing them from transacting on a chain that breaks or alters network rules. Because of its size and complexity, downloading and verifying the entire blockchain is not suitable for all computing devices.

- Lightweight clients consult full nodes to send and receive transactions without requiring a local copy of the entire blockchain (see simplified payment verification – SPV). This makes lightweight clients much faster to set up and allows them to be used on low-power, low-bandwidth devices such as smartphones. When using a lightweight wallet, however, the user must trust full nodes, as it can report faulty values back to the user. Lightweight clients follow the longest blockchain and do not ensure it is valid, requiring trust in full nodes.

Third-party internet services called online wallets or webwallets offer similar functionality but may be easier to use. In this case, credentials to access funds are stored with the online wallet provider rather than on the user's hardware. As a result, the user must have complete trust in the online wallet provider. A malicious provider or a breach in server security may cause entrusted bitcoins to be stolen. An example of such a security breach occurred with Mt. Gox in 2011.

Cold storage

Wallet software is targeted by hackers because of the lucrative potential for stealing bitcoins. A technique called "cold storage" keeps private keys out of reach of hackers; this is accomplished by keeping private keys offline at all times by generating them on a device that is not connected to the internet. The credentials necessary to spend bitcoins can be stored offline in a number of different ways, from specialized hardware wallets to simple paper printouts of the private key.

Hardware wallets

A hardware wallet is a computer peripheral that signs transactions as requested by the user. These devices store private keys and carry out signing and encryption internally, and do not share any sensitive information with the host computer except already signed (and thus unalterable) transactions. Because hardware wallets never expose their private keys, even computers that may be compromised by malware do not have a vector to access or steal them.

The user sets a passcode when setting up a hardware wallet. As hardware wallets are tamper-resistant, the passcode will be needed to extract any money.

Paper wallets

A paper wallet is created with a keypair generated on a computer with no internet connection; the private key is written or printed onto the paper[h] and then erased from the computer. The paper wallet can then be stored in a safe physical location for later retrieval.

Physical wallets can also take the form of metal token coins with a private key accessible under a security hologram in a recess struck on the reverse side. The security hologram self-destructs when removed from the token, showing that the private key has been accessed. Originally, these tokens were struck in brass and other base metals, but later used precious metals as bitcoin grew in value and popularity. Coins with stored face value as high as ₿1000 have been struck in gold. The British Museum's coin collection includes four specimens from the earliest series of funded bitcoin tokens; one is currently on display in the museum's money gallery. In 2013, a Utahn manufacturer of these tokens was ordered by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to register as a money services business before producing any more funded bitcoin tokens.

History

Creation

The domain name bitcoin.org was registered on 18 August 2008. On 31 October 2008, a link to a paper authored by Satoshi Nakamoto titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System was posted to a cryptography mailing list. Nakamoto implemented the bitcoin software as open-source code and released it in January 2009. Nakamoto's identity remains unknown.

On 3 January 2009, the bitcoin network was created when Nakamoto mined the starting block of the chain, known as the genesis block. Embedded in the coinbase of this block was the text "The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks". This note references a headline published by The Times and has been interpreted as both a timestamp and a comment on the instability caused by fractional-reserve banking.

The receiver of the first bitcoin transaction was Hal Finney, who had created the first reusable proof-of-work system (RPoW) in 2004. Finney downloaded the bitcoin software on its release date, and on 12 January 2009 received ten bitcoins from Nakamoto. Other early cypherpunk supporters were creators of bitcoin predecessors: Wei Dai, creator of b-money, and Nick Szabo, creator of bit gold. In 2010, the first known commercial transaction using bitcoin occurred when programmer Laszlo Hanyecz bought two Papa John's pizzas for ₿10,000.

Blockchain analysts estimate that Nakamoto had mined about one million bitcoins before disappearing in 2010 when he handed the network alert key and control of the code repository over to Gavin Andresen. Andresen later became lead developer at the Bitcoin Foundation. Andresen then sought to decentralize control. This left opportunity for controversy to develop over the future development path of bitcoin, in contrast to the perceived authority of Nakamoto's contributions.

2011–2012

After early "proof-of-concept" transactions, the first major users of bitcoin were black markets, such as Silk Road. During its 30 months of existence, beginning in February 2011, Silk Road exclusively accepted bitcoins as payment, transacting 9.9 million in bitcoins, worth about $214 million.

In 2011, the price started at $0.30 per bitcoin, growing to $5.27 for the year. The price rose to $31.50 on 8 June. Within a month, the price fell to $11.00. The next month it fell to $7.80, and in another month to $4.77.

In 2012, bitcoin prices started at $5.27, growing to $13.30 for the year. By 9 January the price had risen to $7.38, but then crashed by 49% to $3.80 over the next 16 days. The price then rose to $16.41 on 17 August, but fell by 57% to $7.10 over the next three days.

The Bitcoin Foundation was founded in September 2012 to promote bitcoin's development and uptake.

On 1 November 2011, the reference implementation Bitcoin-Qt version 0.5.0 was released. It introduced a front end that used the Qt user interface toolkit. The software previously used Berkeley DB for database management. Developers switched to LevelDB in release 0.8 in order to reduce blockchain synchronization time. The update to this release resulted in a minor blockchain fork on 11 March 2013. The fork was resolved shortly afterwards. Seeding nodes through IRC was discontinued in version 0.8.2. From version 0.9.0 the software was renamed to Bitcoin Core. Transaction fees were reduced again by a factor of ten as a means to encourage microtransactions. Although Bitcoin Core does not use OpenSSL for the operation of the network, the software did use OpenSSL for remote procedure calls. Version 0.9.1 was released to remove the network's vulnerability to the Heartbleed bug.

2013–2016

In 2013, prices started at $13.30 rising to $770 by 1 January 2014.

In March 2013 the blockchain temporarily split into two independent chains with different rules due to a bug in version 0.8 of the bitcoin software. The two blockchains operated simultaneously for six hours, each with its own version of the transaction history from the moment of the split. Normal operation was restored when the majority of the network downgraded to version 0.7 of the bitcoin software, selecting the backwards-compatible version of the blockchain. As a result, this blockchain became the longest chain and could be accepted by all participants, regardless of their bitcoin software version. During the split, the Mt. Gox exchange briefly halted bitcoin deposits and the price dropped by 23% to $37 before recovering to the previous level of approximately $48 in the following hours.

The US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) established regulatory guidelines for "decentralized virtual currencies" such as bitcoin, classifying American bitcoin miners who sell their generated bitcoins as Money Service Businesses (MSBs), that are subject to registration or other legal obligations.

In April, exchanges BitInstant and Mt. Gox experienced processing delays due to insufficient capacity resulting in the bitcoin price dropping from $266 to $76 before returning to $160 within six hours. The bitcoin price rose to $259 on 10 April, but then crashed by 83% to $45 over the next three days.

On 15 May 2013, US authorities seized accounts associated with Mt. Gox after discovering it had not registered as a money transmitter with FinCEN in the US. On 23 June 2013, the US Drug Enforcement Administration listed ₿11.02 as a seized asset in a United States Department of Justice seizure notice pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 881. This marked the first time a government agency had seized bitcoin. The FBI seized about ₿30,000 in October 2013 from the dark web website Silk Road, following the arrest of Ross William Ulbricht. These bitcoins were sold at blind auction by the United States Marshals Service to venture capital investor Tim Draper. Bitcoin's price rose to $755 on 19 November and crashed by 50% to $378 the same day. On 30 November 2013, the price reached $1,163 before starting a long-term crash, declining by 87% to $152 in January 2015.

On 5 December 2013, the People's Bank of China prohibited Chinese financial institutions from using bitcoins. After the announcement, the value of bitcoins dropped, and Baidu no longer accepted bitcoins for certain services. Buying real-world goods with any virtual currency had been illegal in China since at least 2009.

In 2014, prices started at $770 and fell to $314 for the year. On 30 July 2014, the Wikimedia Foundation started accepting donations of bitcoin.

In 2015, prices started at $314 and rose to $434 for the year. In 2016, prices rose and climbed up to $998 by 1 January 2017.

Release 0.10 of the software was made public on 16 February 2015. It introduced a consensus library which gave programmers easy access to the rules governing consensus on the network. In version 0.11.2 developers added a new feature which allowed transactions to be made unspendable until a specific time in the future. Bitcoin Core 0.12.1 was released on 15 April 2016, and enabled multiple soft forks to occur concurrently. Around 100 contributors worked on Bitcoin Core 0.13.0 which was released on 23 August 2016.

In July 2016, the CheckSequenceVerify soft fork activated.

In October 2016, Bitcoin Core's 0.13.1 release featured the "Segwit" soft fork that included a scaling improvement aiming to optimize the bitcoin blocksize. The patch which was originally finalised in April, and 35 developers were engaged to deploy it. This release featured Segregated Witness (SegWit) which aimed to place downward pressure on transaction fees as well as increase the maximum transaction capacity of the network. The 0.13.1 release endured extensive testing and research leading to some delays in its release date. SegWit prevents various forms of transaction malleability.

2017–2019

On 15 July 2017, the controversial Segregated Witness [SegWit] software upgrade was approved ("locked-in"). Segwit was intended to support the Lightning Network as well as improve scalability. SegWit was subsequently activated on the network on 24 August 2017. The bitcoin price rose almost 50% in the week following SegWit's approval. On 21 July 2017, bitcoin was trading at $2,748, up 52% from 14 July 2017's $1,835. Supporters of large blocks who were dissatisfied with the activation of SegWit forked the software on 1 August 2017 to create Bitcoin Cash, becoming one of many forks of bitcoin such as Bitcoin Gold.

Prices started at $998 in 2017 and rose to $13,412.44 on 1 January 2018, after reaching its all-time high of $19,783.06 on 17 December 2017.

China banned trading in bitcoin, with first steps taken in September 2017, and a complete ban that started on 1 February 2018. Bitcoin prices then fell from $9,052 to $6,914 on 5 February 2018. The percentage of bitcoin trading in the Chinese renminbi fell from over 90% in September 2017 to less than 1% in June 2018.

Throughout the rest of the first half of 2018, bitcoin's price fluctuated between $11,480 and $5,848. On 1 July 2018, bitcoin's price was $6,343. The price on 1 January 2019 was $3,747, down 72% for 2018 and down 81% since the all-time high.

In September 2018, an anonymous party discovered and reported an invalid-block denial-of-server vulnerability to developers of Bitcoin Core, Bitcoin ABC and Bitcoin Unlimited. Further analysis by bitcoin developers showed the issue could also allow the creation of blocks violating the 21 million coin limit and CVE-2018-17144 was assigned and the issue resolved.

Bitcoin prices were negatively affected by several hacks or thefts from cryptocurrency exchanges, including thefts from Coincheck in January 2018, Bithumb in June, and Bancor in July. For the first six months of 2018, $761 million worth of cryptocurrencies was reported stolen from exchanges. Bitcoin's price was affected even though other cryptocurrencies were stolen at Coinrail and Bancor as investors worried about the security of cryptocurrency exchanges. In September 2019 the Intercontinental Exchange (the owner of the NYSE) began trading of bitcoin futures on its exchange called Bakkt. Bakkt also announced that it would launch options on bitcoin in December 2019. In December 2019, YouTube removed bitcoin and cryptocurrency videos, but later restored the content after judging they had "made the wrong call."

In February 2019, Canadian cryptocurrency exchange Quadriga Fintech Solutions failed with approximately $200 million missing. By June 2019 the price had recovered to $13,000.

2020–present

On 13 March 2020, bitcoin fell below $4,000 during a broad market selloff, after trading above $10,000 in February 2020. On 11 March 2020, 281,000 bitcoins were sold, held by owners for only thirty days. This compared to ₿4,131 that had laid dormant for a year or more, indicating that the vast majority of the bitcoin volatility on that day was from recent buyers. During the week of 11 March 2020, cryptocurrency exchange Kraken experienced an 83% increase in the number of account signups over the week of bitcoin's price collapse, a result of buyers looking to capitalize on the low price. These events were attributed to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In August 2020, MicroStrategy invested $250 million in bitcoin as a treasury reserve asset. In October 2020, Square, Inc. placed approximately 1% of total assets ($50 million) in bitcoin. In November 2020, PayPal announced that US users could buy, hold, or sell bitcoin. On 30 November 2020, the bitcoin value reached a new all-time high of $19,860, topping the previous high of December 2017. Alexander Vinnik, founder of BTC-e, was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for money laundering in France while refusing to testify during his trial. In December 2020 Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company announced a bitcoin purchase of USD $100 million, or roughly 0.04% of its general investment account.

On 19 January 2021, Elon Musk placed the handle #Bitcoin in his Twitter profile, tweeting "In retrospect, it was inevitable", which caused the price to briefly rise about $5000 in an hour to $37,299. On 25 January 2021, Microstrategy announced that it continued to buy bitcoin and as of the same date it had holdings of ₿70,784 worth $2.38 billion. On 8 February 2021 Tesla's announcement of a bitcoin purchase of USD $1.5 billion and the plan to start accepting bitcoin as payment for vehicles, pushed the bitcoin price to $44,141. On 18 February 2021, Elon Musk stated that "owning bitcoin was only a little better than holding conventional cash, but that the slight difference made it a better asset to hold". After 49 days of accepting the digital currency, Tesla reversed course on May 12, 2021, saying they would no longer take Bitcoin due to concerns that "mining" the cryptocurrency was contributing to the consumption of fossil fuels and climate change. The decision resulted in the price of Bitcoin dropping around 12% on May 13. During a July Bitcoin conference, Musk suggested Tesla could possibly help Bitcoin miners switch to renewable energy in the future and also stated at the same conference that if Bitcoin mining reaches, and trends above 50 percent renewable energy usage, that "Tesla would resume accepting bitcoin." The price for bitcoin rose after this announcement.

In September 2020, the Canton of Zug, Switzerland, announced to start to accepting tax payments in bitcoin by February 2021.

In June 2021, the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador voted legislation to make Bitcoin legal tender in El Salvador.[i] The law took effect on September 7. In the same month, a bitcoin network software upgrade called "Taproot", which adds support for Schnorr signatures, and improved functionality of Smart contracts and Lightning Network, was approved with the actual change to the network scheduled for November 2021.

Associated ideologies

Satoshi Nakamoto stated in his white paper that: "The root problem with conventional currencies is all the trust that's required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust."

Austrian economics roots

According to the European Central Bank, the decentralization of money offered by bitcoin has its theoretical roots in the Austrian school of economics, especially with Friedrich von Hayek in his book Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined, in which Hayek advocates a complete free market in the production, distribution and management of money to end the monopoly of central banks.

Anarchism and libertarianism

According to The New York Times, libertarians and anarchists were attracted to the philosophical idea behind bitcoin. Early bitcoin supporter Roger Ver said: "At first, almost everyone who got involved did so for philosophical reasons. We saw bitcoin as a great idea, as a way to separate money from the state." The Economist describes bitcoin as "a techno-anarchist project to create an online version of cash, a way for people to transact without the possibility of interference from malicious governments or banks". Economist Paul Krugman argues that cryptocurrencies like bitcoin are "something of a cult" based in "paranoid fantasies" of government power.

Nigel Dodd argues in The Social Life of Bitcoin that the essence of the bitcoin ideology is to remove money from social, as well as governmental, control. Dodd quotes a YouTube video, with Roger Ver, Jeff Berwick, Charlie Shrem, Andreas Antonopoulos, Gavin Wood, Trace Meyer and other proponents of bitcoin reading The Declaration of Bitcoin's Independence. The declaration includes a message of crypto-anarchism with the words: "Bitcoin is inherently anti-establishment, anti-system, and anti-state. Bitcoin undermines governments and disrupts institutions because bitcoin is fundamentally humanitarian."

David Golumbia says that the ideas influencing bitcoin advocates emerge from right-wing extremist movements such as the Liberty Lobby and the John Birch Society and their anti-Central Bank rhetoric, or, more recently, Ron Paul and Tea Party-style libertarianism. Steve Bannon, who owns a "good stake" in bitcoin, considers it to be "disruptive populism. It takes control back from central authorities. It's revolutionary."

A 2014 study of Google Trends data found correlations between bitcoin-related searches and ones related to computer programming and illegal activity, but not libertarianism or investment topics.

Economics

Bitcoin is a digital asset designed to work in peer-to-peer transactions as a currency. Bitcoins have three qualities useful in a currency, according to The Economist in January 2015: they are "hard to earn, limited in supply and easy to verify." Per some researchers, as of 2015, bitcoin functions more as a payment system than as a currency.

Economists define money as serving the following three purposes: a store of value, a medium of exchange, and a unit of account. According to The Economist in 2014, bitcoin functions best as a medium of exchange. However, this is debated, and a 2018 assessment by The Economist stated that cryptocurrencies met none of these three criteria. Yale economist Robert J. Shiller writes that bitcoin has potential as a unit of account for measuring the relative value of goods, as with Chile's Unidad de Fomento, but that "Bitcoin in its present form [...] doesn't really solve any sensible economic problem".

According to research by Cambridge University, between 2.9 million and 5.8 million unique users used a cryptocurrency wallet in 2017, most of them for bitcoin. The number of users has grown significantly since 2013, when there were 300,000–1.3 million users.

Acceptance by merchants

The overwhelming majority of bitcoin transactions take place on a cryptocurrency exchange, rather than being used in transactions with merchants. Delays processing payments through the blockchain of about ten minutes make bitcoin use very difficult in a retail setting. Prices are not usually quoted in units of bitcoin and many trades involve one, or sometimes two, conversions into conventional currencies. Merchants that do accept bitcoin payments may use payment service providers to perform the conversions.

In 2017 and 2018 bitcoin's acceptance among major online retailers included only three of the top 500 U.S. online merchants, down from five in 2016. Reasons for this decline include high transaction fees due to bitcoin's scalability issues and long transaction times.

Bloomberg reported that the largest 17 crypto merchant-processing services handled $69 million in June 2018, down from $411 million in September 2017. Bitcoin is "not actually usable" for retail transactions because of high costs and the inability to process chargebacks, according to Nicholas Weaver, a researcher quoted by Bloomberg. High price volatility and transaction fees make paying for small retail purchases with bitcoin impractical, according to economist Kim Grauer. However, bitcoin continues to be used for large-item purchases on sites such as Overstock.com, and for cross-border payments to freelancers and other vendors.

Financial institutions

Bitcoins can be bought on digital currency exchanges.

Per researchers, "there is little sign of bitcoin use" in international remittances despite high fees charged by banks and Western Union who compete in this market. The South China Morning Post, however, mentions the use of bitcoin by Hong Kong workers to transfer money home.

In 2014, the National Australia Bank closed accounts of businesses with ties to bitcoin, and HSBC refused to serve a hedge fund with links to bitcoin. Australian banks in general have been reported as closing down bank accounts of operators of businesses involving the currency.

On 10 December 2017, the Chicago Board Options Exchange started trading bitcoin futures, followed by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which started trading bitcoin futures on 17 December 2017.

In September 2019 the Central Bank of Venezuela, at the request of PDVSA, ran tests to determine if bitcoin and ether could be held in central bank's reserves. The request was motivated by oil company's goal to pay its suppliers.

As an investment

The Winklevoss twins have purchased bitcoin. In 2013, The Washington Post reported a claim that they owned 1% of all the bitcoins in existence at the time.

Other methods of investment are bitcoin funds. The first regulated bitcoin fund was established in Jersey in July 2014 and approved by the Jersey Financial Services Commission.

Forbes named bitcoin the best investment of 2013. In 2014, Bloomberg named bitcoin one of its worst investments of the year. In 2015, bitcoin topped Bloomberg's currency tables.

According to bitinfocharts.com, in 2017 there are 9,272 bitcoin wallets with more than $1 million worth of bitcoins. The exact number of bitcoin millionaires is uncertain as a single person can have more than one bitcoin wallet.

In August 2020, MicroStrategy invested in Bitcoin.

In May 2021, the Bitcoin's market share on exchanges dropped from 70% to 45% as investors pursued altcoins.

Venture capital

Peter Thiel's Founders Fund invested US$3 million in BitPay. In 2012, an incubator for bitcoin-focused start-ups was founded by Adam Draper, with financing help from his father, venture capitalist Tim Draper, one of the largest bitcoin holders after winning an auction of 30,000 bitcoins, at the time called "mystery buyer". The company's goal is to fund 100 bitcoin businesses within 2–3 years with $10,000 to $20,000 for a 6% stake. Investors also invest in bitcoin mining. According to a 2015 study by Paolo Tasca, bitcoin startups raised almost $1 billion in three years (Q1 2012 – Q1 2015).

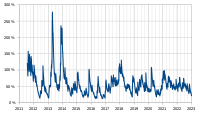

Price and volatility

The price of bitcoins has gone through cycles of appreciation and depreciation referred to by some as bubbles and busts. In 2011, the value of one bitcoin rapidly rose from about US$0.30 to US$32 before returning to US$2. In the latter half of 2012 and during the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis, the bitcoin price began to rise, reaching a high of US$266 on 10 April 2013, before crashing to around US$50. On 29 November 2013, the cost of one bitcoin rose to a peak of US$1,242.[212] In 2014, the price fell sharply, and as of April remained depressed at little more than half 2013 prices. As of August 2014 it was under US$600.

According to Mark T. Williams, as of 30 September 2014, bitcoin has volatility seven times greater than gold, eight times greater than the S&P 500, and 18 times greater than the US dollar. Hodl is a meme created in reference to holding (as opposed to selling) during periods of volatility. Unusual for an asset, bitcoin weekend trading during December 2020 was higher than for weekdays. Hedge funds (using high leverage and derivates) have attempted to use the volatility to profit from downward price movements. At the end of January 2021, such positions were over $1 billion, their highest of all time. As of 8 February 2021, the closing price of bitcoin equals US$44,797.

Legal status, tax and regulation

Because of bitcoin's decentralized nature and its trading on online exchanges located in many countries, regulation of bitcoin has been difficult. However, the use of bitcoin can be criminalized, and shutting down exchanges and the peer-to-peer economy in a given country would constitute a de facto ban. The legal status of bitcoin varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. Regulations and bans that apply to bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.

According to the Library of Congress, an "absolute ban" on trading or using cryptocurrencies applies in nine countries: Algeria, Bolivia, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Vietnam, and the United Arab Emirates. An "implicit ban" applies in another 15 countries, which include Bahrain, Bangladesh, China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Kuwait, Lesotho, Lithuania, Macau, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Taiwan.

In October 2020, the Islamic Republic News Agency announced pending regulations that would require bitcoin miners in Iran to sell bitcoin to the Central Bank of Iran, and the central bank would use it for imports. Iran, as of October 2020, had issued over 1,000 bitcoin mining licenses. The Iranian government initially took a stance against cryptocurrency, but later changed it after seeing that digital currency could be used to circumvent sanctions. The US Office of Foreign Assets Control listed two Iranians and their bitcoin addresses as part of its Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List for their role in the 2018 Atlanta cyberattack whose ransom was paid in bitcoin.

Regulatory warnings

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission has issued four "Customer Advisories" for bitcoin and related investments. A July 2018 warning emphasized that trading in any cryptocurrency is often speculative, and there is a risk of theft from hacking, and fraud. In May 2014 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission warned that investments involving bitcoin might have high rates of fraud, and that investors might be solicited on social media sites. An earlier "Investor Alert" warned about the use of bitcoin in Ponzi schemes.

The European Banking Authority issued a warning in 2013 focusing on the lack of regulation of bitcoin, the chance that exchanges would be hacked, the volatility of bitcoin's price, and general fraud. FINRA and the North American Securities Administrators Association have both issued investor alerts about bitcoin.

Price manipulation investigation

An official investigation into bitcoin traders was reported in May 2018. The U.S. Justice Department launched an investigation into possible price manipulation, including the techniques of spoofing and wash trades.

The U.S. federal investigation was prompted by concerns of possible manipulation during futures settlement dates. The final settlement price of CME bitcoin futures is determined by prices on four exchanges, Bitstamp, Coinbase, itBit and Kraken. Following the first delivery date in January 2018, the CME requested extensive detailed trading information but several of the exchanges refused to provide it and later provided only limited data. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission then subpoenaed the data from the exchanges.

State and provincial securities regulators, coordinated through the North American Securities Administrators Association, are investigating "bitcoin scams" and ICOs in 40 jurisdictions.

Academic research published in the Journal of Monetary Economics concluded that price manipulation occurred during the Mt Gox bitcoin theft and that the market remains vulnerable to manipulation. The history of hacks, fraud and theft involving bitcoin dates back to at least 2011.

Research by John M. Griffin and Amin Shams in 2018 suggests that trading associated with increases in the amount of the Tether cryptocurrency and associated trading at the Bitfinex exchange account for about half of the price increase in bitcoin in late 2017.

J.L. van der Velde, CEO of both Bitfinex and Tether, denied the claims of price manipulation: "Bitfinex nor Tether is, or has ever, engaged in any sort of market or price manipulation. Tether issuances cannot be used to prop up the price of bitcoin or any other coin/token on Bitfinex."

Criticisms

The Bank for International Settlements summarized several criticisms of bitcoin in Chapter V of their 2018 annual report. The criticisms include the lack of stability in bitcoin's price, the high energy consumption, high and variable transactions costs, the poor security and fraud at cryptocurrency exchanges, vulnerability to debasement (from forking), and the influence of miners.

François R. Velde, Senior Economist at the Chicago Fed, described bitcoin as "an elegant solution to the problem of creating a digital currency". David Andolfatto, Vice President at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated that bitcoin is a threat to the establishment, which he argues is a good thing for the Federal Reserve System and other central banks, because it prompts these institutions to operate sound policies.

Economic concerns

Bitcoin, along with other cryptocurrencies, has been described as an economic bubble by at least eight Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences laureates at various times, including Robert Shiller on 1 March 2014, Joseph Stiglitz on 29 November 2017, and Richard Thaler on 21 December 2017. On 29 January 2018, a noted Keynesian economist Paul Krugman has described bitcoin as "a bubble wrapped in techno-mysticism inside a cocoon of libertarian ideology", on 2 February 2018, professor Nouriel Roubini of New York University has called bitcoin the "mother of all bubbles", and on 27 April 2018, a University of Chicago economist James Heckman has compared it to the 17th-century tulip mania.

Journalists, economists, investors, and the central bank of Estonia have voiced concerns that bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme. In April 2013, Eric Posner, a law professor at the University of Chicago, stated that "a real Ponzi scheme takes fraud; bitcoin, by contrast, seems more like a collective delusion." A July 2014 report by the World Bank concluded that bitcoin was not a deliberate Ponzi scheme. In June 2014, the Swiss Federal Council examined concerns that bitcoin might be a pyramid scheme, and concluded that "since in the case of bitcoin the typical promises of profits are lacking, it cannot be assumed that bitcoin is a pyramid scheme."

Energy consumption and carbon footprint

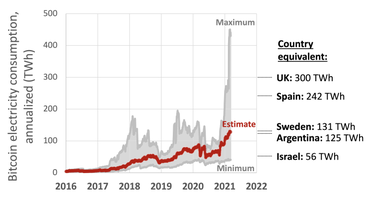

Bitcoin has been criticized for the amount of electricity consumed by mining.

As of 2015, estimated combined electricity consumption attributed to mining was 166.7 megawatts and by 2017, was estimated to be between one and four gigawatts of electricity. In 2018, bitcoin was estimated to use 2.55 to 3.572 GW, or around 6% of the total power consumed by the global banking sector. In July 2019 BBC reported bitcoin consumes about 7 gigawatts, 0.2% of the global total, or equivalent to that of Switzerland. A 2021 estimate from the University of Cambridge suggests bitcoin consumes more than 178 (TWh) annually, ranking it in the top 30 energy consumers if it were a country.

Bitcoin is mined in places like Iceland where geothermal energy is cheap and cooling Arctic air is free. Bitcoin miners are known to use hydroelectric power in Tibet, Quebec, Washington (state), and Austria to reduce electricity costs. Miners are attracted to suppliers such as Hydro Quebec that have energy surpluses.

According to a University of Cambridge study, much of bitcoin mining is done in China, where electricity is subsidized by the government. A significant part of Bitcoin mining is powered by cheap electricity in Xinjiang, which mostly comes from coal power. In April 2021 a coal mine explosion in the province coincided with a 35% drop in hashing power and a flash crash in price. In other provinces, such as Hunan and Sichuan, mining farms use more hydropower, however these account for at most 4% of hash power. According to Alex de Vries, renewable energy is not a good match for Bitcoin mining as 24/7 operations are best for ROI on mining devices. In 2021, a US company purchased the Greenidge coal power plant and converted it to burn natural gas for the sole purpose of mining bitcoin, which has proven to be highly profitable, in spite of protests of local residents against air pollution and thermal pollution in the nearby Seneca lake.

Concerns about bitcoin's environmental impact relate bitcoin's energy consumption to carbon emissions.

The difficulty of translating the energy consumption into carbon

emissions lies in the decentralized nature of bitcoin impeding the

localization of miners to examine the electricity mix used. The results

of recent studies analyzing bitcoin's carbon footprint vary. A study published in Nature Climate Change in 2018 claims that bitcoin "could alone produce enough CO

2 emissions to push warming above 2 °C within less than three decades."

However, other researchers criticized this analysis, arguing the

underlying scenarios were inadequate, leading to overestimations. According to studies published in Joule and American Chemical Society in 2019, bitcoin's annual energy consumption results in annual carbon emission ranging from 17 to 22.9 MtCO

2 which is comparable to the level of emissions of countries as Jordan and Sri Lanka or Kansas City. George Kamiya, writing for the International Energy Agency,

says that "predictions about bitcoin consuming the entire world's

electricity" are sensational, but that the area "requires careful

monitoring and rigorous analysis".

Use in illegal transactions

Bitcoin held at exchanges are vulnerable to theft through phishing, scamming, and hacking. As of December 2017, around 980,000 bitcoins have been stolen from cryptocurrency exchanges.

The use of bitcoin by criminals has attracted the attention of financial regulators, legislative bodies, law enforcement, and the media. Bitcoin gained early notoriety for its use on the Silk Road. The U.S. Senate held a hearing on virtual currencies in November 2013. The U.S. government claimed that bitcoin was used to facilitate payments related to Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections. However, a 2021 study led by former CIA director Michael Morell showed that broad generalizations about the use of bitcoin in illicit finance are significantly overstated and that blockchain analysis is an effective crime fighting and intelligence gathering tool.

Several news outlets have asserted that the popularity of bitcoins hinges on the ability to use them to purchase illegal goods. Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says that bitcoin's anonymity encourages money laundering and other crimes.

In 2014, researchers at the University of Kentucky found "robust evidence that computer programming enthusiasts and illegal activity drive interest in bitcoin, and find limited or no support for political and investment motives". Australian researchers have estimated that 25% of all bitcoin users and 44% of all bitcoin transactions are associated with illegal activity as of April 2017. There were an estimated 24 million bitcoin users primarily using bitcoin for illegal activity. They held $8 billion worth of bitcoin, and made 36 million transactions valued at $72 billion.

Software implementation

The start screen under Fedora | |

| Original author(s) | Satoshi Nakamoto |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 2009 |

| Stable release | 22.0 (13 September 2021) [±] |

| Repository | github |

| Written in | C++ |

| Operating system | Linux, Windows, macOS |

| Type | Cryptocurrency |

| License | MIT License |

| Website | bitcoincore |

Bitcoin Core is free and open-source software that serves as a bitcoin node (the set of which form the bitcoin network) and provides a bitcoin wallet which fully verifies payments. It is considered to be bitcoin's reference implementation. Initially, the software was published by Satoshi Nakamoto under the name "Bitcoin", and later renamed to "Bitcoin Core" to distinguish it from the network. It is also known as the Satoshi client.

The MIT Digital Currency Initiative funds some of the development of Bitcoin Core. The project also maintains the cryptography library libsecp256k1.

Bitcoin Core includes a transaction verification engine and connects to the bitcoin network as a full node. Moreover, a cryptocurrency wallet, which can be used to transfer funds, is included by default. The wallet allows for the sending and receiving of bitcoins. It does not facilitate the buying or selling of bitcoin. It allows users to generate to receive payment.

The software validates the entire blockchain, which includes all bitcoin transactions ever. This distributed ledger which has reached more than 235 gigabytes in size as of Jan 2019, must be downloaded or synchronized before full participation of the client may occur. Although the complete blockchain is not needed all at once since it is possible to run in pruning mode. A command line-based daemon with a JSON-RPC interface, bitcoind, is bundled with Bitcoin Core. It also provides access to testnet, a global testing environment that imitates the bitcoin main network using an alternative blockchain where valueless "test bitcoins" are used. Regtest or Regression Test Mode creates a private blockchain which is used as a local testing environment. Finally, bitcoin-cli, a simple program which allows users to send RPC commands to bitcoind, is also included.

Checkpoints which have been hard coded into the client are used only to prevent Denial of Service attacks against nodes which are initially syncing the chain. For this reason the checkpoints included are only as of several years ago. A one megabyte block size limit was added in 2010 by Satoshi Nakamoto. This limited the maximum network capacity to about three transactions per second. Since then, network capacity has been improved incrementally both through block size increases and improved wallet behavior. A network alert system was included by Satoshi Nakamoto as a way of informing users of important news regarding bitcoin. In November 2016 it was retired. It had become obsolete as news on bitcoin is now widely disseminated.

Bitcoin Core includes a scripting language inspired by Forth that can define transactions and specify parameters. ScriptPubKey is used to "lock" transactions based on a set of future conditions. scriptSig is used to meet these conditions or "unlock" a transaction. Operations on the data are performed by various OP_Codes. Two stacks are used - main and alt. Looping is forbidden.

Bitcoin Core uses OpenTimestamps to timestamp merge commits.

The original creator of the bitcoin client has described their approach to the software's authorship as it being written first to prove to themselves that the concept of purely peer-to-peer electronic cash was valid and that a paper with solutions could be written. The lead developer is Wladimir J. van der Laan, who took over the role on 8 April 2014. Gavin Andresen was the former lead maintainer for the software client. Andresen left the role of lead developer for bitcoin to work on the strategic development of its technology. Bitcoin Core in 2015 was central to a dispute with Bitcoin XT, a competing client that sought to increase the blocksize. Over a dozen different companies and industry groups fund the development of Bitcoin Core.

In popular culture

Term "HODL"

Hodl (/ˈhɒdəl/ HOD-əl; often written HODL) is slang in the cryptocurrency community for holding a cryptocurrency rather than selling it. A person who does this is known as a Hodler. It originated in a December 2013 post on the Bitcoin Forum message board by an apparently inebriated user who posted with a typo in the subject, "I AM HODLING." It is often humorously suggested to be a backronym to "hold on for dear life". In 2017, Quartz listed it as one of the essential slang terms in Bitcoin culture, and described it as a stance, "to stay invested in bitcoin and not to capitulate in the face of plunging prices." TheStreet.com referred to it as the "favorite mantra" of Bitcoin holders. Bloomberg News referred to it as a mantra for holders during market routs.

Literature

In Charles Stross' 2013 science fiction novel, Neptune's Brood, the universal interstellar payment system is known as "bitcoin" and operates using cryptography. Stross later blogged that the reference was intentional, saying "I wrote Neptune's Brood in 2011. Bitcoin was obscure back then, and I figured had just enough name recognition to be a useful term for an interstellar currency: it'd clue people in that it was a networked digital currency."

Film

The 2014 documentary The Rise and Rise of Bitcoin portrays the diversity of motives behind the use of bitcoin by interviewing people who use it. These include a computer programmer and a drug dealer. The 2016 documentary Banking on Bitcoin is an introduction to the beginnings of bitcoin and the ideas behind cryptocurrency today.

Academia

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It covers studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh. The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.