Free-market anarchism, or market anarchism, also known as free-market anti-capitalism and free-market socialism, is the branch of anarchism that advocates a free-market economic system based on voluntary interactions without the involvement of the state. A form of individualist anarchism, left-libertarianism and market socialism, it is based on the economic theories of mutualism and individualist anarchism in the United States. Left-wing market anarchism is a modern branch of free-market anarchism that is based on a revival of such free-market anarchist theories. It is associated with left-libertarians such as Kevin Carson and Gary Chartier, who consider themselves anti-capitalists and socialists.

Samuel Edward Konkin III's agorism is a strand of left-wing market anarchism that has been associated with left-libertarianism in the United States, with counter-economics being its means. Anarcho-capitalism, a form of right-libertarianism, has been occasionally referred to as free-market anarchism or market anarchism, among other names. Anarcho-capitalists stress the legitimacy and priority of private property, without any distinction between personal property and productive property, describing it as an integral component of individual rights and a free-market economy. However, anarcho-capitalism is not considered as part of the anarchist movement because anarchism has historically been an anti-capitalist movement and anarchists reject that it is compatible with capitalism. In addition, an analysis of individualist anarchists who advocated free-market anarchism shows that it is different from anarcho-capitalism and other capitalist theories due to the individualist anarchists retaining the labor theory of value and socialist doctrines.

Free-market anarchism may refer to diverse economic and political concepts like those proposed by individualist anarchists and libertarian socialists such as the Europeans Émile Armand, Thomas Hodgskin, Miguel Giménez Igualada and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, or the Americans Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Batchelder Greene, Lysander Spooner, Benjamin Tucker and Josiah Warren, among others; and occasionally anarcho-capitalists such as David D. Friedman or various anti-capitalists, left-libertarians and left-wing market anarchists such as Carson, Chartier, Charles W. Johnson, Konkin, Roderick T. Long, Sheldon Richman, Chris Matthew Sciabarra and Brad Spangler.

History

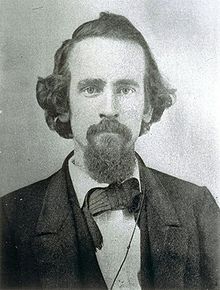

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published, an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates. Warren was a follower of Robert Owen and joined Owen's community at New Harmony, Indiana. Josiah Warren termed the phrase "cost the limit of price", with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item. Therefore, "he proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce". He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included Utopia and Modern Times. Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' The Science of Society, published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories. Catalan historian Xavier Diez report that the intentional communal experiments pioneered by Warren were influential in European individualist anarchists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Émile Armand and the intentional communities started by them.

Mutualism began in 18th-century English and French labour movements before taking an anarchist form associated with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in France and others in the United States. Proudhon proposed spontaneous order, whereby organisation emerges without central authority, a "positive anarchy" where order arises when everybody does "what he wishes and only what he wishes" and where "business transactions alone produce the social order". It is important to recognize that Proudhon distinguished between ideal political possibilities and practical governance. For this reason, much in contrast to some of his theoretical statements concerning ultimate spontaneous self-governance, Proudhon was heavily involved in French parliamentary politics and allied himself not with Anarchist but Socialist factions of workers movements and in addition to advocating state-protected charters for worker-owned cooperatives, promoted certain nationalization schemes during his life of public service. Mutualist anarchism is concerned with reciprocity, free association, voluntary contract, federation and credit and currency reform. According to the American mutualist William Batchelder Greene, each worker in the mutualist system would receive "just and exact pay for his work; services equivalent in cost being exchangeable for services equivalent in cost, without profit or discount". Mutualism has been retrospectively characterised as ideologically situated between individualist and collectivist forms of anarchism. Proudhon first characterised his goal as a "third form of society, the synthesis of communism and property".

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a French activist and theorist, the founder of mutualist philosophy, an economist and a libertarian socialist. He was the first person to declare himself an anarchist and is among its most influential theorists. He is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He became a member of the French Parliament after the Revolution of 1848, whereupon and thereafter he referred to himself as a federalist. Proudhon, who was born in Besançon, was a printer who taught himself Latin in order to better print books in the language. His best-known assertion is that "property is theft!", contained in his first major work What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government (Qu'est-ce que la propriété? Recherche sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement), published in 1840. The book's publication attracted the attention of the French authorities. It also attracted the scrutiny of Karl Marx, who started a correspondence with its author. The two influenced each other and met in Paris while Marx was exiled there. Their friendship finally ended when Marx responded to Proudhon's The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty with the provocatively titled The Poverty of Philosophy. The dispute became one of the sources of the split between the anarchist and Marxian wings of the International Workingmen's Association. Some, such as Edmund Wilson, have contended that Marx's attack on Proudhon had its origin in the latter's defense of Karl Grün, whom Marx bitterly disliked but who had been preparing translations of Proudhon's work. Proudhon favored workers' associations or co-operatives as well as individual worker/peasant possession over private ownership or the nationalization of land and workplaces. He considered social revolution to be achievable in a peaceful manner. In The Confessions of a Revolutionary Proudhon asserted that "Anarchy is Order Without Power", the phrase which much later inspired, in the view of some, the anarchist circled-A symbol, today "one of the most common graffiti on the urban landscape". He unsuccessfully tried to create a national bank to be funded by what became an abortive attempt at an income tax on capitalists and shareholders. Similar in some respects to a credit union, it would have given interest-free loans.

William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister, soldier and promoter of free banking in the United States. Greene is best known for the works Mutual Banking (1850), which proposed an interest-free banking system; and Transcendentalism, a critique of the New England philosophical school. American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster states: "It is apparent that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form". After 1850, he became active in labor reform and was elected vice-president of the New England Labor Reform League, the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual banking. In 1869, he was elected president of the Massachusetts Labor Union. Greene then published Socialistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments (1875). He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order". His "associationism is checked by individualism. 'Mind your own business,' "Judge not that ye be not judged". Over matters which are purely personal, as for example moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands "mutuality" in marriage – the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property".

Individualist anarchism in the United States

A form of individualist anarchism was found in the United States as advocated by the Boston anarchists. Most American Individualist Anarchists advocate mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics. Individualist anarchists are opposed to property that gives privilege and is exploitative, seeking to "destroy the tyranny of capital, — that is, of property" by mutual credit. Some Boston anarchists, including Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner, identified themselves as socialists, a label often used in the 19th century in the sense of a commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. the labor problem). The Boston anarchists such as Tucker and his followers are also considered socialists due to their opposition to usury. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed, On the other hand, anarchist historian George Woodcock describes Spooner's essays as an "eloquent elaboration" of Josiah Warren and the early American development of Proudhon's ideas and associates his works with that of Stephen Pearl Andrews. Woodcock also reports that both Spooner and Greene had been members of the socialist First International.

American individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker identified as a socialist and argued that the elimination of what he called the four monopolies, namely the land monopoly, the money and banking monopoly, the monopoly powers conferred by patents and the quasi-monopolistic effects of tariffs, would undermine the power of the wealthy and big business, making possible widespread property ownership and higher incomes for ordinary people, while minimizing the power of would-be bosses and achieving socialist goals without state action. Tucker influenced and interacted with anarchist contemporaries, including Lysander Spooner, Voltairine de Cleyre, Dyer Lum and William Batchelder Greene, who have in various ways influenced later left-libertarian thinking. Kevin Carson characterizes American individualist anarchism by saying: "Unlike the rest of the socialist movement, the individualist anarchists believed that the natural wage of labor in a free market was its product and that economic exploitation could only take place when capitalists and landlords harnessed the power of the state in their interests. Thus, individualist anarchism was an alternative both to the increasing statism of the mainstream socialist movement and to a liberal movement that was moving toward a mere apologetic for the power of big business. Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's Liberty were also important labor organizers of the time. Joseph Labadie and Dyer Lum. Kevin Carson has praised Lum's fusion of individualist laissez-faire economics with radical labor activism as "creative" and described him as "more significant than any in the Boston group".

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract". He also said after converting to egoist individualism: "In times past it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off. Man's only right to land is his might over it". In adopting Stirnerite egoism in 1886, Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. So bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly.

Individualist anarchism in Europe

Geolibertarianism, a libertarian form of Henry George's philosophy called geoism, is considered left-libertarian because it assumes land to be initially owned in common, so that when land is privately appropriated the proprietor pays rent to the community. Geolibertarians generally advocate distributing the land rent to the community via a land value tax as proposed by Henry George and others before him. For this reason, they are often called "single taxers". Fred E. Foldvary coined the term geo-libertarianism in a Land and Liberty article. In the case of geoanarchism, the voluntary form of geolibertarianism as described by Foldvary, rent would be collected by private associations with the opportunity to secede from the rent-sharing community and not receive the community's services.

Similar economic positions also existed within European individualist anarchism. French individualist anarchist Émile Armand shows clearly opposition to capitalism and centralized economies when he said that the individualist anarchist "inwardly he remains refractory – fatally refractory – morally, intellectually, economically (The capitalist economy and the directed economy, the speculators and the fabricators of single are equally repugnant to him.)". He argued for a pluralistic economic logic when he said: "Here and there everything happening – here everyone receiving what they need, there each one getting whatever is needed according to their own capacity. Here, gift and barter – one product for another; there, exchange – product for representative value. Here, the producer is the owner of the product, there, the product is put to the possession of the collectivity".

Spanish individualist anarchist Miguel Giménez Igualada thought that "capitalism is an effect of government; the disappearance of government means capitalism falls from its pedestal vertiginously. That which we call capitalism is not something else but a product of the State, within which the only thing that is being pushed forward is profit, good or badly acquired. And so to fight against capitalism is a pointless task, since be it State capitalism or Enterprise capitalism, as long as Government exists, exploiting capital will exist. The fight, but of consciousness, is against the State". His view on class division and technocracy are as follows: "Since when no one works for another, the profiteer from wealth disappears, just as government will disappear when no one pays attention to those who learned four things at universities and from that fact they pretend to govern men. Big industrial enterprises will be transformed by men in big associations in which everyone will work and enjoy the product of their work. And from those easy as well as beautiful problems anarchism deals with and he who puts them in practice and lives them are anarchists. The priority which without rest an anarchist must make is that in which no one has to exploit anyone, no man to no man, since that non-exploitation will lead to the limitation of property to individual needs".

Alliance between libertarians and the New Left in the United States

The doyen of modern American market-oriented libertarianism, Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard, was initially an enthusiastic partisan of the Old Right, particularly because of its general opposition to war and imperialism. However, Rothbard had long embraced a reading of American history that emphasized the role of elite privilege in shaping legal and political institutions—one that was naturally agreeable to many on the left—and came increasingly in the 1960s to seek alliances on the left—especially with members of the New Left—in light of the Vietnam War, the military draft and the emergence of the Black Power movement.

Working with other likeminded people like Ronald Radosh and Karl Hess, Rothbard argued that the consensus view of American economic history, according to which a beneficent government has used its power to counter corporate predation, is fundamentally flawed. Rather, he argued, government intervention in the economy has largely benefited established players at the expense of marginalized groups, to the detriment of both liberty and equality. Moreover, the robber baron period, hailed by the right and despised by the left as a heyday of laissez-faire, was not characterized by laissez-faire at all, but it was in fact a time of massive state privilege accorded to capital. In tandem with his emphasis on the intimate connection between state and corporate power, he defended the seizure of corporations dependent on state largesse by workers and others.

Rothbard himself ultimately broke with the left, allying himself instead with the burgeoning paleoconservative movement. Drawing on the work of Rothbard during his alliance with the left and on the thought of Karl Hess, some thinkers associated with market-oriented American libertarianism came increasingly to identify with the left on a range of issues, including opposition to war, to corporate oligopolies and to state-corporate partnerships as well as an affinity for cultural liberalism. One variety of this kind of libertarianism has been a resurgent mutualism, incorporating modern economic ideas such as marginal utility theory into mutualist theory. Kevin Carson's Studies in Mutualist Political Economy helped to stimulate the growth of new-style mutualism, articulating a version of the labor theory of value incorporating ideas drawn from Austrian economics. Other market-oriented left-libertarians have declined to embrace mutualist views of real property while sharing the mutualist opposition to corporate hierarchies and wealth concentration. Left-libertarians have placed particular emphasis on the articulation and defense of a libertarian theory of class and class conflict, although considerable work in this area has been performed by libertarians of other persuasions.

Left-wing market anarchism

Left-wing market anarchism is a contemporary school of left-libertarianism and a revival of the free-market anarchist theories of mutualism and 19th century individualist anarchism. It is associated with scholars such as Kevin Carson, Gary Chartier, Charles W. Johnson, Samuel Edward Konkin III, Roderick T. Long, Sheldon Richman, Chris Matthew Sciabarra and Brad Spangler, who stress the value of radically free markets, termed freed markets to distinguish them from the common conception which these libertarians believe to be riddled with statist and capitalist privileges. Referred to as left-wing market anarchists, market-oriented or free-market left-libertarians, proponents of this approach distinguish themselves from right-libertarians and strongly affirm the classical liberal ideas of self-ownership and free markets while maintaining that taken to their logical conclusions these ideas support strongly anti-capitalist, anti-corporatist, anti-hierarchical and pro-labor positions in economics; anti-imperialism in foreign policy; and thoroughly liberal or radical views regarding issues such as class, gender, sexuality and race. This strand of left-libertarianism tends to be rooted either in the mutualist economics conceptualized by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, American individualist anarchism, or in a left-wing interpretation or extension of the thought of Murray Rothbard. These left-libertarians rejects "what critics call "atomistic individualism". With freed markets, they argue that "it is we collectively who decide who controls the means of production", leading to "a society in which free, voluntary, and peaceful cooperation ultimately controls the means of production for the good of all people".

According to libertarian scholar Sheldon Richman, left-libertarians "favor worker solidarity vis-à-vis bosses, support poor people's squatting on government or abandoned property, and prefer that corporate privileges be repealed before the regulatory restrictions on how those privileges may be exercised", seeing Walmart as a "symbol of corporate favoritism" which is "supported by highway subsidies and eminent domain", viewing "the fictive personhood of the limited-liability corporation with suspicion" and "doubt[ing] that Third World sweatshops would be the "best alternative" in the absence of government manipulation". These left-libertarians "tend to eschew electoral politics, having little confidence in strategies that work through the government. They prefer to develop alternative institutions and methods of working around the state".

Gary Chartier has joined Kevin Carson, Charles W. Johnson and others (echoing the language of Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Batchelder Greene, Thomas Hodgskin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Lysander Spooner, Benjamin Tucker and Josiah Warren, among others) in maintaining that because of its heritage and its emancipatory goals and potential, radical market anarchism should be seen by its proponents and by others as part of the socialist tradition and that market anarchists can and should call themselves socialists.

Forms of geolibertarianism also fit into this group, but these geoists are less likely to accept terms such as anti-capitalist or socialist. While adopting familiar libertarian views, including opposition to civil liberties violations, drug prohibition, gun control, imperialism and war, left-libertarians are more likely than most self-identified libertarians to take more distinctively leftist stances on issues as diverse as class, egalitarianism, environmentalism, feminism, gender, immigration, race, sexuality and war. Contemporary free-market left-libertarians show markedly more sympathy than American mainstream libertarians or paleolibertarians towards various cultural movements which challenge non-governmental relations of power. Left-libertarians such as Long and Johnson have called for a recovery of the 19th-century alliance with libertarian feminism and radical liberalism.

Especially influential regarding these topics have been scholars including Long, Johnson, Sciabarra and Arthur Silber. The genealogy of contemporary market-oriented left-libertarianism, sometimes labeled left-wing market anarchism, overlaps to a significant degree with that of Steiner–Vallentyne left-libertarianism as the roots of that tradition are sketched in The Origins of Left-Libertarianism. Carson–Long-style left-libertarianism is rooted in 19th-century mutualism and in the work of figures such as the British Thomas Hodgskin and Anarchists within American individualist anarchism such as Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner. While with notable exceptions market-oriented libertarians after Tucker tended to ally with the political right, relationships between such libertarians and the New Left thrived in the 1960s, laying the groundwork for modern left-wing market anarchism.

The Really Really Free Market movement is a horizontally organized collective of individuals who form a temporary market based on an alternative gift economy. The movement aims to counteract capitalism in a proactive way by creating a positive example to challenge the myths of scarcity and competition. The name itself is a play on words as it is a reinterpretation and re-envisioning of free market, a term which generally refers to an economy of consumerism governed by supply and demand.

Criticism

David McNally of the University of Houston argues in the Marxist tradition that the logic of the market inherently produces inequitable outcomes and leads to unequal exchanges, arguing that Adam Smith's moral intent and moral philosophy espousing equal exchange was undermined by the practice of the free market he championed. According to McNally, the development of the market economy involved coercion, exploitation and violence that Smith's moral philosophy could not countenance. McNally criticizes free-market anarchism and other market socialists for believing in the possibility of fair markets based on equal exchanges to be achieved by purging parasitical elements from the market economy such as private ownership of the means of production, arguing that market socialism is an oxymoron when socialism is defined as an end to wage labour.