- The Seikilos column with the Seikilos epitaph, dated to the 2nd-Century CE or later

- Sculptures on the Jagdish Temple, Udaipur of musicians, one of which plays an instrument similar to the Rudra veena

- Mountain Chief recording on a phonograph for Frances Densmore, 1916

- Performers in the Samba de Roda festival, a music and dance celebration in the Bahia region of Brazil

- A man playing the gendèr outside of the Embassy of Indonesia, Canberra

- A man playing the didgeridoo, an indigenous instrument of Australia

- Joseph Haydn playing in a string quartet, in a painting from before 1790

The history of music covers the historical development and presence of music from prehistoric times to present day. Though definitions of music vary wildly throughout the world, every known culture partakes in it, and music is thus considered a cultural universal. The origins of music remain highly contentious; commentators often relate it to the origin of language, with much disagreement surrounding whether music arose before, after or simultaneously with language. Many other theories exist, having been proposed by scholars from a wide range of disciplines, though none have achieved wide approval. Most cultures have their own mythical origins concerning the invention of music, generally rooted in their respective mythological, religious or philosophical beliefs.

The music of prehistoric cultures is first firmly dated to c. 40,000 BP of the Upper Paleolithic by evidence of bone flutes, though it remains unclear whether or not the actual origins lie in the earlier Middle Paleolithic period (300,000 to 50,000 BP). There is little known about prehistoric music, with traces mainly limited to iconographical evidence, as well as some simple flutes and percussion instruments. However, such evidence indicates that music existed to some extent in prehistoric societies such as the Xia dynasty and the Indus Valley Civilisation. Upon the development of writing, the music of literate civilizations—ancient music—was present in the major Chinese, Egyptian, Greek, Indian, Persian, Mesopotamian and Middle Eastern societies. It is difficult to make many generalizations about ancient music as a whole, but from what is known it was often characterized by monophony and improvisation. In ancient song forms, the texts were closely aligned with music, and though the oldest extant musical notation survives from this period, many texts survive without their accompanying music, such as the Rigveda and the Shijing Classic of Poetry. The eventual emergence of the Silk Road and increasing contact between cultures led to the transmission and exchange of musical ideas, practices and instruments.

Historically, religions have often been catalysts for music. The Vedas of Hinduism immensely influenced Indian classical music, while the Five Classics of Confucianism laid the basis for subsequent Chinese music. Following the rapid spread of Islam in the 6th century, Islamic music dominated Persia and the Arab world, and the Islamic Golden Age saw the presence of numerous important music theorists. Music written for and by the early Christian Church properly inaugurates the Western classical music tradition, which continues into medieval music where polyphony, staff notation and nascent forms of many modern instruments developed. In addition to religion, or the lack thereof, a society's music is influenced by all other aspects of its culture, including social and economic organization and experience, climate and access to technology. Many cultures have coupled music with other art forms, such as the Chinese four arts and the medieval quadrivium. The emotions and ideas that music expresses, the situations in which music is played and listened to, and the attitudes toward musicians and composers all vary between regions and periods. Many cultures have or continue to distinguish between art music (or 'classical music'), folk music and more recently, popular music.

Origins

"But that music is a language by whose means messages are elaborated, that such messages can be understood by the many but sent out only by the few, and that it alone among all language unites the contradictory character of being at once intelligible and untranslatable—these facts make the creator of music a being like the gods and make music itself the supreme mystery of human knowledge."

It remains debated as to what extent the origin of human cognition—and thus music—will ever be understood, with scholars often taking polarizing positions. The origin of music is regularly discussed as intrinsically linked with the origin of language, with the nature of their connection being a subject of serious debate. However, before the mid-late 20th century, both topics were seldom given substantial attention by scholars. Since recent resurgence in the topic, the principal source of contention is whether music began as a type of proto-language and a product of adaptation that led to language, if music is a spandrel (a phenotypic byproduct of evolution) that was the result of language or if music and language derived from a common antecedent. A well known take on the second is from cognitive psychologist and linguist Steven Pinker; in his How the Mind Works (1997), Pinker famously termed music as merely "auditory cheesecake", an analogy relating to his view of music as a spandrel, arguing that "as far as biological cause and effect is concerned, music is useless", and that "it is a technology, not an adaptation". Music psychologist Sandra Trehub notes that, like Pinker, "much of the larger scientific community is highly skeptical about links between music and biology", in opposition to specialists on the subjects. Scholars such as Joseph Carroll and Anna K. Tirovolas have rejected Pinker's take, citing evolutionary advantages including its use as practice for cognitive flexibility and "indicating to potential mates [one's] cognitive and physical flexibility and fitness".

There is little consensus on any particular theory for the origin of music, which have included contributions from archaeologists, cognitive scientists, ethnomusicologists, evolutionary biologists, linguists, neuroscientists, paleoanthropologists, philosophers and psychologists (developmental and social). Theories on the topic can be differentiated in two ways: structural models, which see music as an outgrowth of preexisting abilities, and functional models which consider its emergence as an adaptive technique. Taking the latter approach is perhaps the first significant theory on the origins of music: Charles Darwin's 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, where he briefly proposed that music was originally an elaborate form of sexual selection, perhaps arising in mating calls. His theory is difficult to affirm, as there is no evidence that either sex is "more musical" thus no evidence of sexual dimorphism; there are currently no other examples of sexual selection that do not include considerable sexual dimorphism. However, citing music's use in other animals's mating systems, commentators such as Peter J.B. Slater, Katy Payne, Björn Merker, Geoffrey Miller and Peter Todd have promoted developed versions of Darwin's theory. Other theories suggest that music was developed to assist in "coordination, cohesion and cooperation", or as part of parental care, where parents use music to increase communication with—and thus the survivability of—their children. Some commentators propose music arose alongside language, both of which supposably descend from a "shared precursor", which the composer Richard Wagner termed "speech-music".

Many cultures have their own mythical origins on the creation of music. In Chinese mythology, there are various stories, the most prominent being from the Lüshi Chunqiu which says in 2697 BCE, the musician Ling Lun—on the orders of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi)—invented bamboo flute by imitating the song of the mythical fenghuang birds. The invention of music in Ancient Greek mythology is credited to the muses, various goddesses who were daughters of the King of the gods, Zeus; Apollo, Dionysus and Orpheus were also important musical figures for the Ancient Greeks. Persian/Iranian mythology holds that Jamshid, a legendary Shah, invented music. In Christian mythology, Jubal is called "the father of all those who play the lyre and the pipe" in Genesis 4:21, and may thus be identifiable as an originator of music for Christians. Saraswati is the god of music in Hinduism, while Väinämöinen holds a similar status as an early musical figure in Finnish folklore.

Prehistoric music

In the broadest sense, prehistoric music—more commonly termed primitive music in the past—encompasses all music produced in preliterate cultures (prehistory), beginning at least 6 million years ago when humans and chimpanzees last had a common ancestor. Music first arose in the Paleolithic period, though it remains unclear as to whether this was the Middle (300,000 to 50,000 BP) or Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 12,000 BP). The vast majority of Paleolithic instruments have been found in Europe and date to the Upper Paleolithic. It is certainly possible that singing emerged far before this time, though this is essentially impossible to confirm. The potentially oldest instrument is the Divje Babe Flute from the Divje Babe cave in Slovenia, dated to 43,000 and 82,000 and made from a young cave bear femur. Purportedly used by Neanderthals, the Divje Babe Flute has received extensive scholarly attention, and whether it is truly a musical instrument or an object formed by animals is the subject of intense debate. If the former, it would be the oldest known musical instrument and evidence of a musical culture in the Middle Paleolithic. Other than the Divje Babe Flute and three other doubtful flutes, there is virtually no surviving Middle Paleolithic musical evidence of any certainty, similar to the situation in regards to visual art. The earliest objects whose designations as musical instruments are widely accepted are bone flutes from the Swabian Jura, Germany, namely from the Geissenklösterle, Hohle Fels and Vogelherd caves. Dated to the Aurignacian (of the Upper Paleolithic) and used by Early European modern humans, from all three caves there are eight examples, four made from the wing bones of birds and four from mammoth ivory; three of these are near complete. Three flutes from the Geissenklösterle are dated as the oldest, c. 43,150–39,370 BP.

Considering the relative complexity of flutes, it is likely earlier instruments existed, akin to objects that are common in later hunter and gatherer societies, such as rattles, shakers and drums. The absence of other instruments from and before this time may be due to their use of weaker—and thus more biodegradable—materials, such as reeds, gourds, skins, and bark. A painting in the Cave of the Trois-Frères dating to c. 15,000 BCE is thought to depict a shaman playing a musical bow.

Prehistoric cultures are thought to have had a wide variety of uses for music, with little unification between different societies. Music was likely in particular value when food and other basic needs were scarce. It is also probable that prehistoric cultures viewed music as intrinsically connected with nature, and may have believed its use influenced the natural world directly.

The earliest instruments found in prehistoric China are 12 gudi bone flutes in the modern-day Jiahu, Wuyang, Henan Province from c. 6000 BCE. The only instruments dated to the prehistoric Xia dynasty (c. 2070–1600) are two qing, two small bells (one earthenware, one bronze) and a xun. Due to this extreme scarcity of surviving instruments and the general uncertainty surrounding most of the Xia, creating a musical narrative of the period is impractical. In the Indian subcontinent, the prehistoric Indus Valley Civilisation (from c. 2500–2000 BCE in its mature state) has archeological evidence that indicates simple rattles and vessel flutes were used, while iconographical evidence suggests early harps and drums also existed. An ideogram in the later IVC contains the earliest known depiction of an arched harp, dated sometime before 1800 BCE.

Ancient music

Following the advent of writing, literate civilizations are termed part of the ancient world, a periodization which extends from the first Sumerian literature of Abu Salabikh (now Southern Iraq) of c. 2600 BCE, until the Post-classical era of the 6th century CE. Though the music of Ancient societies was extremely diverse, some fundamental concepts arise prominently in virtually all of them, namely monophony, improvisation and the dominance of text in musical settings. Varying song forms were present in Ancient cultures, including China, Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia, Rome and the Middle East. The text, rhythm and melodies of these songs were closely aligned, as was music in general, with magic, science and religion. Complex song forms developed in later ancient societies, particularly the national festivals of China, Greece and India. Later Ancient societies also saw increased trade and transmission of musical ideas and instruments, often shepherded by the Silk Road. For example, a tuning key for a qin-zither from 4th–5th centuries BCE China includes considerable Persian iconography. In general, not enough information exists to make many other generalizations about ancient music.

The few actual examples of ancient music notation that survive usually exist on papyrus or clay tablets. Information on musical practices, genres and thought is mainly available through literature, visual depictions and increasingly as the period progresses, instruments. The oldest surviving written music is the Hurrian songs from Ugarit, Syria. Of these, the oldest is the Hymn to Nikkal (hymn no. 6; h. 6), which is somewhat complete and dated to c. 1400 BCE. However, the Seikilos epitaph is the earliest entirely complete noted musical composition. Dated to the 2nd-Century CE or later, it is an epitaph, perhaps for the wife of the unknown Seikilos.

China

Shang and Zhou

They strike the bells, kin, kin,

They play the se-zither, play the qin-zither,

The mouth organ and chime stones sound together;

They sing the Ya and Nan Odes,

And perform flawlessly upon their flutes.

Shijing, Ode 208, Gu Zhong

Translated by John S. Major

By the mid-13th century BCE, the late Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) had developed writing, which mostly exists as divinatory inscriptions on the ritualistic oracle bones but also as bronze inscriptions. As many as 11 oracle script characters may refer to music to some extent, some of which could be iconographical representations of instruments themselves. The stone bells qing appears to have been particularly popular with the Shang ruling class, and while no surviving flutes have been dated to the Shang, oracle script evidence suggests they used ocarinas (xun), transverse flute (xiao and dizi), douple pipes, the mouthorgan (sheng), and maybe the pan flute (paixiao). Due to the advent of the bronze in 2000 BCE, the Shang used the material for bells—the ling (鈴), nao (鐃) and zhong (鐘)—that can be differentiated in two ways: those with or without a clapper and those struck on the inside or outside. Drums, which are not found from before the Shang, sometimes used bronze, though they were more often wooden (bangu). The aforementioned wind instruments certainly existed by the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), as did the first Chinese string instruments: the guqin (or qin) and se zithers.[66][n 19] The Zhou saw the emergence of major court ensembles and the well known Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (after 433 BCE) contains a variety of complex and decorated instruments. Of the tomb, the by-far most notable instrument is the monumental set of 65 tuned bianzhong bells, which range five octaves requiring at least five players; they are still playable and include rare inscriptions on music.

Ancient Chinese instruments served both practical and ceremonial means. People used them to appeal to supernatural forces for survival needs, while pan flutes may have been used to attract birds while hunting, and drums were common in sacrifices and military ceremonies. Chinese music has always been closely associated with dance, literature and fine arts; many early Chinese thinkers also equated music with proper morality and governance of society. Throughout the Shang and Zhou music was a symbol of power for the Imperial court, being utilized in religious services as well as the celebration of ancestors and heroes. Confucius (c. 551–479) formally designated the music concerned with ritual and ideal morality as the superior yayue (雅樂; "proper music"), in opposition to suyue (俗樂; "vernacular/popular music"), which included virtually all non-ceremonial music, but particularly any that was considered excessive or lascivious. During the Warring States Period when of Confucius's lifetime, officials often ignored this distinction, preferring more lively suyue music and using the older yayue traditional solely for political means. Confucius and disciples such as Mencius considered this preference virtueless and saw ill of the leaders' ignorance of ganying, a theory that held music was intrinsically connected to the universe. Thus, many aspects of Ancient Chinese music were aligned with cosmology: the 12 pitch shí-èr-lǜ system corresponded equally with certain weights and measurements; the pentatonic scale with the five wuxing; and the eight tone classification of Chinese instruments of bayin with the eight symbols of bagua. No actual music or texts on the performance practices of Ancient Chinese musicians survive. The Five Classics of the Zhou dynasty include musical commentary; the I Ching and Chunqiu Spring and Autumn Annals make references, while the Liji Book of Rites contains a substantial discussion (see the chapter Yue Ji Record of Music). While the Yue Jing Classic of Music is lost, the Shijing Classic of Poetry contains 160 texts to now lost songs from the Western Zhou period (1045–771).

Qin and Han

The Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), established by Qin Shi Huang, lasted for only 15 years, but the purported burning of books resulted in a substantial loss of previous musical literature. The Qin saw the guzheng become a particularly popular instrument; as a more portable and louder zither, it meet the needs of an emerging popular music scene. During the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), there were attempts to reconstruct the music of the Shang and Zhou, as it was now "idealized as perfect". A Music Bureau, the Yuefu, was founded or at its height by at least 120 BCE under Emperor Wu of Han, and was responsible for collecting folksongs. The purpose of this was twofold; it allowed the Imperial Court to properly understand the thoughts of the common people, and it was also an opportunity for the Imperial Court to adapt and manipulate the songs to suit propaganda and political purposes. Employing ceremonial, entertainment-oriented and military musicians, the Bureau also performed at a variety of venues, wrote new music, and set music to commissioned poetry by noted figures such as Sima Xiangru. The Han dynasty had officially adopted Confucianism as the state philosophy, and the ganying theories became a dominant philosophy. In practice, however, many officials ignored or downplayed Confucius's high regard for yayue over suyue music, preferring to engage in the more lively and informal later. By 7 BCE the Bureau employed 829 musicians; that year Emperor Ai either disbanded or downsized the department, due to financial limitations, and the Bureau's increasingly prominent suyue music which conflicted with Confucianism. The Han dynasty saw a preponderance of foreign musical influences from the Middle East and Central Asia: the emerging Silk Road led to the exchange of musical instruments, and allowed travelers such as Zhang Qian to relay with new musical genres and techniques. Instruments from said cultural transmission include metal trumpets and instruments similar to the modern oboe and oud lute, the latter which became the pipa. Other preexisting instruments greatly increased in popularity, such as the qing, panpipes, and particularly the qin, which was from then on the most revered instrument, associated with good character and morality.

Greece

Greek written history extends far back into Ancient Greece, and was a major part of ancient Greek theatre. In ancient Greece, mixed-gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration and spiritual reasons. Instruments included the most important wind instrument, the double-reed aulos, as well as the plucked string instrument, the lyre, especially the special kind called a kithara.

India

The principal sources on the music of ancient India are textual and iconographical; specifically, some theoretical treatises in Sanskrit survive, there are brief mentions in general literature and many sculptures of Ancient Indian musicians and their instruments exist. Ancient Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit literature frequently contains musical references, from the Vedas to the works of Kalidasa and the Ilango Adigal's epic Silappatikaram.[122] Despite this, little is known on the actual musical practices of ancient India and the information available forces a somewhat homogeneous perspective on the music of the time, even though evidence indicates that in reality it was far more diverse.

The monumental arts treatise Natya Shastra is among the earliest and chief sources for Ancient Indian music; the music portions alone are likely from the Gupta period (4th century to 6th century CE). The religious text Rigveda has elements of present Indian music, with a musical notation to denote the metre and the mode of chanting.

Persia and Mesopotamia

Up to the Achaemenid period

In general, it is impossible to create a thorough outline of the earliest music in Persia due to a paucity of surviving records. Evidenced by c. 3300–3100 BCE Elam depictions, arched harps are the first affirmation Persian music, though it is probable that they existed well before their artistic depictions. Elamite bull lyres from c. 2450 have been found in Susa, while more than 40 small Oxus trumpets have been found in Bactria and Margiana, dated to the c. 2200–1750 Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex. The oxus trumpets seem to have had a close association with both religion and animals; a Zoroastrian myth in which Jamshid attract animals with the trumpet suggests that the Elamites used them for hunting. In many ways the earliest known musical cultures of Iran are strongly connected with those of Mesopotamia. Ancient arched harps (c. 3000) also exist in the latter and the scarcity of instruments make it unclear as to which culture the harp originated. Far more bull lyres survive in Ur of Mesopotamia, notably the Bull Headed Lyre of Ur, though they are nearly identical to their contemporary Elamite counterparts. From evidence in terracotta plaques, by the 2nd-century BCE the arched harp was displaced by the angular harps, which existed in 20-string vertical and nine-string horizontal variants. Lutes were purportedly used in Mesopotamia by at least 2300 BCE, but not until c. 1300 BCE do the appear in Iran, where they became the dominant string instruments of Western Iran, though the available evidence suggests its popularity was outside of the elite. The rock reliefs of Kul-e Farah show that sophisticated Persian court ensembles emerged in the 1st-century BCE, in the which the central instrument was the arched harp. The prominence of musicians in these certain rock reliefs suggests they were essential in religious ceremonies.

Like earlier periods, extremely little contemporary information on the music of the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE) exists. Most knowledge on the Achaemenid musical culture comes from Greek historians. In his Histories, Herodotus noted that Achamenid priests did not use aulos music in their ceremonies, while Xenophon reflected on his visit to Persia in the Cyropaedia, mentioning the presence of many female singers at court. Athenaeus also mentions female singers when noting that 329 of them had been taken from the King of Kings Darius III by Macedonian general Parmenion. Later Persian texts assert that gōsān poet-musician minstrels were prominent and of considerable status in court.

Parthian and Sasanian periods

The Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE) saw an increase in textual and iconographical depictions of musical activity and instruments. 2nd century BCE Parthian rhuta (drinking horns) found in the ancient capital of Nisa include some of the most vivid depictions of musicians from the time. Pictorial evidence such as terracotta plaques show female harpists, while plaques from Babylon show panpipess, as well as string (harps, lutes and lyres) and percussion instruments (tambourines and clappers). Bronze statues from Dura-Europos depict larger panpipes and a double aulos. Music was evidently used in ceremonies and celebrations; a Parthian-era stone frieze in Hatra shows a wedding where musicians are included, playing trumpets, tambourines and a variety of flutes. Other textual and iconographical evidence indicates the continued prominence of gōsān minstrels. However, like the Achaemenid period, Greek writers continue to be a major source for information on Parthian music. Strabo recorded that the gōsān learned songs telling tales of gods and noble men, while Plutarch similarly records the gōsān lauding Parthian heroes and mocking Roman ones. Plutarch also records, much to his bafflement, that rhoptra (large drums) were used by the Parthian army to prepare for war.

The Sasanian period (226–651 CE), however, has left ample evidence of music. This influx of Sasanian records suggests a prominent musical culture in the Empire, especially in the areas dominated by Zoroastrianism. Many Sassanian Shahanshahs were ardent supporters of music, including the founder of the empire Ardashir I and Bahram V. Khosrow II (r. 590–628) was the most outstanding patron, his reign being regarded as a golden age of Persian music. Musicians in Khosrow's service include Āzādvar-e Changi,[n 26] Bamshad, the harpist Nagisa (Nakisa), Ramtin, Sarkash and Barbad, who was the most famous. These musicians were usually active as minstrels, which were performers who worked as both court poets and musicians; in the Sassanian Empire there was little distinction between poetry and music.

Other Arab and African cultures

The Western African Nok culture (modern-day Nigeria) existed from c. 500–200 BCE and left a considerable amount of sculptures. Among these are depictions of music, such as a man who shakes two objects thought to be maracas. Another sculpture includes a man with his mouth opening (possibly singing) while there is also a sculpture of a man playing a drum.

Post-classical music

Medieval

Modern scholars generally define 'Medieval music' as the music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. Music was certainly prominent in the Early Middle Ages, as attested by artistic depictions of instruments, writings about music, and other records; however, the only repertory of music which has survived from before 800 to the present day is the plainsong liturgical music of the Roman Catholic Church, the largest part of which is called Gregorian chant. Pope Gregory I, who gave his name to the musical repertory and may himself have been a composer, is usually claimed to be the originator of the musical portion of the liturgy in its present form, though the sources giving details on his contribution date from more than a hundred years after his death. Many scholars believe that his reputation has been exaggerated by legend. Most of the chant repertory was composed anonymously in the centuries between the time of Gregory and Charlemagne.

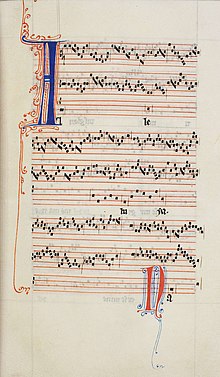

During the 9th century several important developments took place. First, there was a major effort by the Church to unify the many chant traditions, and suppress many of them in favor of the Gregorian liturgy. Second, the earliest polyphonic music was sung, a form of parallel singing known as organum. Third, and of greatest significance for music history, notation was reinvented after a lapse of about five hundred years, though it would be several more centuries before a system of pitch and rhythm notation evolved having the precision and flexibility that modern musicians take for granted.

Several schools of polyphony flourished in the period after 1100: the St. Martial school of organum, the music of which was often characterized by a swiftly moving part over a single sustained line; the Notre Dame school of polyphony, which included the composers Léonin and Pérotin, and which produced the first music for more than two parts around 1200; the musical melting-pot of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, a pilgrimage destination and site where musicians from many traditions came together in the late Middle Ages, the music of whom survives in the Codex Calixtinus; and the English school, the music of which survives in the Worcester Fragments and the Old Hall Manuscript. Alongside these schools of sacred music a vibrant tradition of secular song developed, as exemplified in the music of the troubadours, trouvères and Minnesänger. Much of the later secular music of the early Renaissance evolved from the forms, ideas, and the musical aesthetic of the troubadours, courtly poets and itinerant musicians, whose culture was largely exterminated during the Albigensian Crusade in the early 13th century.

Forms of sacred music which developed during the late 13th century included the motet, conductus, discant, and clausulae. One unusual development was the Geisslerlieder, the music of wandering bands of flagellants during two periods: the middle of the 13th century (until they were suppressed by the Church); and the period during and immediately following the Black Death, around 1350, when their activities were vividly recorded and well-documented with notated music. Their music mixed folk song styles with penitential or apocalyptic texts. The 14th century in European music history is dominated by the style of the ars nova, which by convention is grouped with the medieval era in music, even though it had much in common with early Renaissance ideals and aesthetics. Much of the surviving music of the time is secular, and tends to use the formes fixes: the ballade, the virelai, the lai, the rondeau, which correspond to poetic forms of the same names. Most pieces in these forms are for one to three voices, likely with instrumental accompaniment: famous composers include Guillaume de Machaut and Francesco Landini.

Byzantine

Prominent and diverse musical practices were present in the Byzantine Empire, which existed by 395 to 1453. Both sacred and secular music were commonplace, with sacred music frequently used in church services and secular music in many events including, ceremonies dramas, ballets, banquets, festivals and sports games. However, despite its popularity, secular Byzantine music was harshly criticized by the Church Fathers. Composers of sacred music, especially hymns and chants, are generally well documented throughout the history of Byzantine music. However, those before the reign of Justinian I are virtually unknown; the monks Anthimos, Auxentios and Timokles are said to have written troparia, but only the text to a single one by Auxentios survives. The first major form was the kontakion, of which Romanos the Melodist was the foremost composer. In the late 7th century the kanōn overtook the kontakion in popularity; Andrew of Crete became its first significant composer, and is traditionally credited as the genre's originator, though modern scholars now doubt this attribution. The kañon reached its peak with the music of John of Damascus and Cosmas of Maiuma and later Theodore of Stoudios and Theophanes the Branded in the 8th and 9th centuries respectively. Composers of secular music are considerably less documented. Not until late in the empire's history are composers known by name, with Joannes Koukouzeles, Xenos Korones and Joannes Glykys as the leading figures.

Like their Western counterparts of the same period, Byzantine composers were primarily men. Kassia is a major exception to this; she was a prolific and important composer of sticheron hymns and the only woman whose works entered the Byzantine liturgy. A few other women are known to have been composers, Thekla, Theodosia, Martha and the daughter of John Kladas (her given name is unrecorded). Only the latter has any surviving work, a single antiphon. Some Byzantine emperors are known to have been composers, such as Leo VI the Wise and Constantine VII.

Early modern and modern music

Indian classical music

During the ancient and medieval periods, the classical music of the Indian subcontinent was a largely unified practice. By the 14th century, socio-political turmoil inaugurated by the Delhi Sultanate began to isolate Northern and Southern India, and independent traditions in each region began emerging. By the 16th-century two distinct styles had formed: the Hindustani classical music of the North and the Carnatic classical music of the South. One of the major differences between them is that the Northern Hindustani vein was considerably influenced by the Persian and Arab musical practices of the time. Carnatic music is largely devotional; the majority of the songs are addressed to the Hindu deities.

Indian classical music (marga) is monophonic and based on a single melody line or raga rhythmically organized through talas.

Western classical music

Renaissance

The beginning of the Renaissance in music is not as clearly marked as the beginning of the Renaissance in the other arts, and unlike in the other arts, it did not begin in Italy, but in northern Europe, specifically in the area currently comprising central and northern France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. The style of the Burgundian composers, as the first generation of the Franco-Flemish school is known, was at first a reaction against the excessive complexity and mannered style of the late 14th century ars subtilior, and contained clear, singable melody and balanced polyphony in all voices. The most famous composers of the Burgundian school in the mid-15th century are Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, and Antoine Busnois.

By the middle of the 15th century, composers and singers from the Low Countries and adjacent areas began to spread across Europe, especially into Italy, where they were employed by the papal chapel and the aristocratic patrons of the arts (such as the Medici, the Este, and the Sforza families). They carried their style with them: smooth polyphony which could be adapted for sacred or secular use as appropriate. Principal forms of sacred musical composition at the time were the mass, the motet, and the laude; secular forms included the chanson, the frottola, and later the madrigal.

The invention of printing had an immense influence on the dissemination of musical styles, and along with the movement of the Franco-Flemish musicians, contributed to the establishment of the first truly international style in European music since the unification of Gregorian chant under Charlemagne. Composers of the middle generation of the Franco-Flemish school included Johannes Ockeghem, who wrote music in a contrapuntally complex style, with varied texture and an elaborate use of canonical devices; Jacob Obrecht, one of the most famous composers of masses in the last decades of the 15th century; and Josquin des Prez, probably the most famous composer in Europe before Palestrina, and who during the 16th century was renowned as one of the greatest artists in any form. Music in the generation after Josquin explored increasing complexity of counterpoint; possibly the most extreme expression is in the music of Nicolas Gombert, whose contrapuntal complexities influenced early instrumental music, such as the canzona and the ricercar, ultimately culminating in Baroque fugal forms.

By the middle of the 16th century, the international style began to break down, and several highly diverse stylistic trends became evident: a trend towards simplicity in sacred music, as directed by the Counter-Reformation Council of Trent, exemplified in the music of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina; a trend towards complexity and chromaticism in the madrigal, which reached its extreme expression in the avant-garde style of the Ferrara School of Luzzaschi and the late century madrigalist Carlo Gesualdo; and the grandiose, sonorous music of the Venetian school, which used the architecture of the Basilica San Marco di Venezia to create antiphonal contrasts. The music of the Venetian school included the development of orchestration, ornamented instrumental parts, and continuo bass parts, all of which occurred within a span of several decades around 1600. Famous composers in Venice included the Gabrielis, Andrea and Giovanni, as well as Claudio Monteverdi, one of the most significant innovators at the end of the era.

Most parts of Europe had active and well-differentiated musical traditions by late in the century. In England, composers such as Thomas Tallis and William Byrd wrote sacred music in a style similar to that written on the continent, while an active group of home-grown madrigalists adapted the Italian form for English tastes: famous composers included Thomas Morley, John Wilbye and Thomas Weelkes. Spain developed instrumental and vocal styles of its own, with Tomás Luis de Victoria writing refined music similar to that of Palestrina, and numerous other composers writing for the new guitar. Germany cultivated polyphonic forms built on the Protestant chorales, which replaced the Roman Catholic Gregorian Chant as a basis for sacred music, and imported the style of the Venetian school (the appearance of which defined the start of the Baroque era there). In addition, German composers wrote enormous amounts of organ music, establishing the basis for the later Baroque organ style which culminated in the work of J.S. Bach. France developed a unique style of musical diction known as musique mesurée, used in secular chansons, with composers such as Guillaume Costeley and Claude Le Jeune prominent in the movement.

One of the most revolutionary movements in the era took place in Florence in the 1570s and 1580s, with the work of the Florentine Camerata, who ironically had a reactionary intent: dissatisfied with what they saw as contemporary musical depravities, their goal was to restore the music of the ancient Greeks. Chief among them were Vincenzo Galilei, the father of the astronomer, and Giulio Caccini. The fruits of their labors was a declamatory melodic singing style known as monody, and a corresponding staged dramatic form: a form known today as opera. The first operas, written around 1600, also define the end of the Renaissance and the beginning of the Baroque eras.

Music prior to 1600 was modal rather than tonal. Several theoretical developments late in the 16th century, such as the writings on scales on modes by Gioseffo Zarlino and Franchinus Gaffurius, led directly to the development of common practice tonality. The major and minor scales began to predominate over the old church modes, a feature which was at first most obvious at cadential points in compositions, but gradually became pervasive. Music after 1600, beginning with the tonal music of the Baroque era, is often referred to as belonging to the common practice period.

Baroque

The Baroque era took place from 1600 to 1750, as the Baroque artistic style flourished across Europe and, during this time, music expanded in its range and complexity. Baroque music began when the first operas (dramatic solo vocal music accompanied by orchestra) were written. During the Baroque era, polyphonic contrapuntal music, in which multiple, simultaneous independent melody lines were used, remained important (counterpoint was important in the vocal music of the Medieval era). German, Italian, French, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, Portuguese, and English Baroque composers wrote for small ensembles including strings, brass, and woodwinds, as well as for choirs and keyboard instruments such as pipe organ, harpsichord, and clavichord. During this period several major music forms were defined that lasted into later periods when they were expanded and evolved further, including the fugue, the invention, the sonata, and the concerto. The late Baroque style was polyphonically complex and richly ornamented. Important composers from the Baroque era include Johann Sebastian Bach, Arcangelo Corelli, François Couperin, Girolamo Frescobaldi, George Frideric Handel, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Claudio Monteverdi, Georg Philipp Telemann and Antonio Vivaldi.

Classical

The music of the Classical period is characterized by homophonic texture, or an obvious melody with accompaniment. These new melodies tended to be almost voice-like and singable, allowing composers to actually replace singers as the focus of the music. Instrumental music therefore quickly replaced opera and other sung forms (such as oratorio) as the favorite of the musical audience and the epitome of great composition. However, opera did not disappear: during the classical period, several composers began producing operas for the general public in their native languages (previous operas were generally in Italian).

Along with the gradual displacement of the voice in favor of stronger, clearer melodies, counterpoint also typically became a decorative flourish, often used near the end of a work or for a single movement. In its stead, simple patterns, such as arpeggios and, in piano music, Alberti bass (an accompaniment with a repeated pattern typically in the left hand), were used to liven the movement of the piece without creating a confusing additional voice. The now-popular instrumental music was dominated by several well-defined forms: the sonata, the symphony, and the concerto, though none of these were specifically defined or taught at the time as they are now in music theory. All three derive from sonata form, which is both the overlying form of an entire work and the structure of a single movement. Sonata form matured during the Classical era to become the primary form of instrumental compositions throughout the 19th century.

The early Classical period was ushered in by the Mannheim School, which included such composers as Johann Stamitz, Franz Xaver Richter, Carl Stamitz, and Christian Cannabich. It exerted a profound influence on Joseph Haydn and, through him, on all subsequent European music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was the central figure of the Classical period, and his phenomenal and varied output in all genres defines our perception of the period. Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert were transitional composers, leading into the Romantic period, with their expansion of existing genres, forms, and even functions of music.

Romantic

In the Romantic period, music became more expressive and emotional, expanding to encompass literature, art, and philosophy. Famous early Romantic composers include Schumann, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Bellini, Donizetti, and Berlioz. The late 19th century saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the orchestra, and in the role of concerts as part of urban society. Famous composers from the second half of the century include Johann Strauss II, Brahms, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and Wagner. Between 1890 and 1910, a third wave of composers including Grieg, Dvořák, Mahler, Richard Strauss, Puccini, and Sibelius built on the work of middle Romantic composers to create even more complex – and often much longer – musical works. A prominent mark of late 19th century music is its nationalistic fervor, as exemplified by such figures as Dvořák, Sibelius, and Grieg. Other prominent late-century figures include Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Rachmaninoff, Franck, Debussy and Rimsky-Korsakov.

20th and 21st-century music

Music of all kinds also became increasingly portable. The 20th century saw a revolution in music listening as the radio gained popularity worldwide and new media and technologies were developed to record, capture, reproduce and distribute music. Music performances became increasingly visual with the broadcast and recording of performances.

20th-century music brought a new freedom and wide experimentation with new musical styles and forms that challenged the accepted rules of music of earlier periods. The invention of musical amplification and electronic instruments, especially the synthesizer, in the mid-20th century revolutionized classical and popular music, and accelerated the development of new forms of music.

As for classical music, two fundamental schools determined the course of the century: that of Arnold Schoenberg and that of Igor Stravinsky. However, other composers also had a notable influence. For example: Béla Bartók, Anton Webern, Dmitri Shostakovich, Olivier Messiaen, John Cage, Benjamin Britten, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Sofya Gubaidulina, Krzysztof Penderecki, Brian Ferneyhough, Kaija Saariaho.

The 20th century saw the unprecedented dissemination of popular music, that is, music with a wide appeal. The term has its roots in the music of the American Tin Pan Alley, a group of prominent the began during the 1880s in New York City. Although popular music sometimes is known as "pop music", the two terms are not interchangeable. Popular music is a generic term for a wide variety of genres of music that appeal to the tastes of a large segment of the population, whereas pop music usually refers to a specific musical genre within popular music. Popular music songs and pieces typically have easily singable melodies. The song structure of popular music commonly involves repetition of sections, with the verse and chorus or refrain repeating throughout the song and the bridge providing a contrasting and transitional section within a piece.