| Alcoholism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Alcohol addiction, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol use disorder (AUD) |

| |

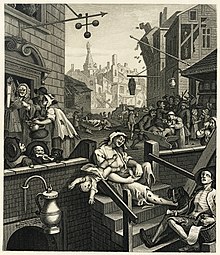

| A French temperance organisation poster depicting the effects of alcoholism in a family, c. 1915 | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology, toxicology, addiction medicine |

| Symptoms | Drinking large amounts of alcohol over a long period, difficulty cutting down, acquiring and drinking alcohol taking up a lot of time, usage resulting in problems, withdrawal occurring when stopping |

| Complications | Mental illness, delirium, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, irregular heartbeat, cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, suicide |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic factors |

| Risk factors | Stress, anxiety, inexpensive, easy access |

| Diagnostic method | Questionnaires, blood tests |

| Treatment | Alcohol cessation typically with benzodiazepines, counselling, acamprosate, disulfiram, naltrexone |

| Frequency | 380 million / 5.1% adults (2016) |

| Deaths | 3.3 million / 5.9% |

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word "alcoholism", it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predominant diagnostic classifications are alcohol use disorder (DSM-5) or alcohol dependence (ICD-11); these are defined in their respective sources.

Excessive alcohol use can damage all organ systems, but it particularly affects the brain, heart, liver, pancreas and immune system. Alcoholism can result in mental illness, delirium tremens, Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, irregular heartbeat, an impaired immune response, liver cirrhosis and increased cancer risk. Drinking during pregnancy can result in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Women are generally more sensitive than men to the harmful effects of alcohol, primarily due to their smaller body weight, lower capacity to metabolize alcohol, and higher proportion of body fat. In a small number of individuals, prolonged, severe alcohol misuse ultimately leads to cognitive impairment and frank dementia.

Environment and genetics are two factors in the risk of development of alcoholism, with about half the risk attributed to each. Stress and associated disorders, including anxiety, are key factors in the development of alcoholism as alcohol consumption can temporarily reduce dysphoria. Someone with a parent or sibling with an alcohol use disorder is three to four times more likely to develop an alcohol use disorder themselves, but only a minority of them do. Environmental factors include social, cultural and behavioral influences. High stress levels and anxiety, as well as alcohol's inexpensive cost and easy accessibility, increase the risk. People may continue to drink partly to prevent or improve symptoms of withdrawal. After a person stops drinking alcohol, they may experience a low level of withdrawal lasting for months. Medically, alcoholism is considered both a physical and mental illness. Questionnaires are usually used to detect possible alcoholism. Further information is then collected to confirm the diagnosis.

Prevention of alcoholism may be attempted by reducing the experience of stress and anxiety in individuals. It can be attempted by regulating and limiting the sale of alcohol (particularly to minors), taxing alcohol to increase its cost, and providing education and treatment.

Treatment of alcoholism may take several forms. Due to medical problems that can occur during withdrawal, alcohol cessation should be controlled carefully. One common method involves the use of benzodiazepine medications, such as diazepam. These can be taken while admitted to a health care institution or individually. The medications acamprosate, disulfiram or naltrexone may also be used to help prevent further drinking. Mental illness or other addictions may complicate treatment. Various forms of individual or group therapy or support groups are used to attempt to keep a person from returning to alcoholism. One support group is Alcoholics Anonymous.

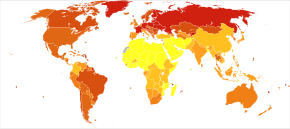

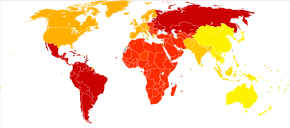

The World Health Organization has estimated that as of 2016, there were 380 million people with alcoholism worldwide (5.1% of the population over 15 years of age). As of 2015 in the United States, about 17 million (7%) of adults and 0.7 million (2.8%) of those age 12 to 17 years of age are affected. Alcoholism is most common among males and young adults. Geographically, it is least common in Africa (1.1% of the population) and has the highest rates in Eastern Europe (11%). Alcoholism directly resulted in 139,000 deaths in 2013, up from 112,000 deaths in 1990. A total of 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all deaths) are believed to be due to alcohol. Alcoholism reduces a person's life expectancy by approximately ten years. Many terms, some slurs and others informal, have been used to refer to people affected by alcoholism; the expressions include tippler, drunkard, dipsomaniac and souse. In 1979, the World Health Organization discouraged the use of "alcoholism" due to its inexact meaning, preferring "alcohol dependence syndrome".

Signs and symptoms

The risk of alcohol dependence begins at low levels of drinking and increases directly with both the volume of alcohol consumed and a pattern of drinking larger amounts on an occasion, to the point of intoxication, which is sometimes called "binge drinking".

Long-term misuse

Alcoholism is characterised by an increased tolerance to alcohol – which means that an individual can consume more alcohol – and physical dependence on alcohol, which makes it hard for an individual to control their consumption. The physical dependency caused by alcohol can lead to an affected individual having a very strong urge to drink alcohol. These characteristics play a role in decreasing the ability to stop drinking of an individual with an alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism can have adverse effects on mental health, contributing to psychiatric disorders and increasing the risk of suicide. A depressed mood is a common symptom of heavy alcohol drinkers.

Warning signs

Warning signs of alcoholism include the consumption of increasing amounts of alcohol and frequent intoxication, preoccupation with drinking to the exclusion of other activities, promises to quit drinking and failure to keep those promises, the inability to remember what was said or done while drinking (colloquially known as "blackouts"), personality changes associated with drinking, denial or the making of excuses for drinking, the refusal to admit excessive drinking, dysfunction or other problems at work or school, the loss of interest in personal appearance or hygiene, marital and economic problems, and the complaint of poor health, with loss of appetite, respiratory infections, or increased anxiety.

Physical

Short-term effects

Drinking enough to cause a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.03–0.12% typically causes an overall improvement in mood and possible euphoria (a "happy" feeling), increased self-confidence and sociability, decreased anxiety, a flushed, red appearance in the face and impaired judgment and fine muscle coordination. A BAC of 0.09% to 0.25% causes lethargy, sedation, balance problems and blurred vision. A BAC of 0.18% to 0.30% causes profound confusion, impaired speech (e.g. slurred speech), staggering, dizziness and vomiting. A BAC from 0.25% to 0.40% causes stupor, unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, vomiting (death may occur due to inhalation of vomit while unconscious) and respiratory depression (potentially life-threatening). A BAC from 0.35% to 0.80% causes a coma (unconsciousness), life-threatening respiratory depression and possibly fatal alcohol poisoning. With all alcoholic beverages, drinking while driving, operating an aircraft or heavy machinery increases the risk of an accident; many countries have penalties for drunk driving.

Long-term effects

Having more than one drink a day for women or two drinks for men increases the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, and stroke. Risk is greater with binge drinking, which may also result in violence or accidents. About 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all deaths) are believed to be due to alcohol each year. Alcoholism reduces a person's life expectancy by around ten years and alcohol use is the third leading cause of early death in the United States. No professional medical association recommends that people who are nondrinkers should start drinking. Long-term alcohol misuse can cause a number of physical symptoms, including cirrhosis of the liver, pancreatitis, epilepsy, polyneuropathy, alcoholic dementia, heart disease, nutritional deficiencies, peptic ulcers and sexual dysfunction, and can eventually be fatal. Other physical effects include an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, malabsorption, alcoholic liver disease, and several cancers. Damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system can occur from sustained alcohol consumption. A wide range of immunologic defects can result and there may be a generalized skeletal fragility, in addition to a recognized tendency to accidental injury, resulting a propensity to bone fractures.

Women develop long-term complications of alcohol dependence more rapidly than do men. Additionally, women have a higher mortality rate from alcoholism than men. Examples of long-term complications include brain, heart, and liver damage and an increased risk of breast cancer. Additionally, heavy drinking over time has been found to have a negative effect on reproductive functioning in women. This results in reproductive dysfunction such as anovulation, decreased ovarian mass, problems or irregularity of the menstrual cycle, and early menopause. Alcoholic ketoacidosis can occur in individuals who chronically misuse alcohol and have a recent history of binge drinking. The amount of alcohol that can be biologically processed and its effects differ between sexes. Equal dosages of alcohol consumed by men and women generally result in women having higher blood alcohol concentrations (BACs), since women generally have a lower weight and higher percentage of body fat and therefore a lower volume of distribution for alcohol than men.

Psychiatric

Long-term misuse of alcohol can cause a wide range of mental health problems. Severe cognitive problems are common; approximately 10 percent of all dementia cases are related to alcohol consumption, making it the second leading cause of dementia. Excessive alcohol use causes damage to brain function, and psychological health can be increasingly affected over time. Social skills are significantly impaired in people suffering from alcoholism due to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol on the brain, especially the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The social skills that are impaired by alcohol use disorder include impairments in perceiving facial emotions, prosody, perception problems, and theory of mind deficits; the ability to understand humor is also impaired in people who misuse alcohol. Psychiatric disorders are common in people with alcohol use disorders, with as many as 25 percent suffering severe psychiatric disturbances. The most prevalent psychiatric symptoms are anxiety and depression disorders. Psychiatric symptoms usually initially worsen during alcohol withdrawal, but typically improve or disappear with continued abstinence. Psychosis, confusion, and organic brain syndrome may be caused by alcohol misuse, which can lead to a misdiagnosis such as schizophrenia. Panic disorder can develop or worsen as a direct result of long-term alcohol misuse.

The co-occurrence of major depressive disorder and alcoholism is well documented. Among those with comorbid occurrences, a distinction is commonly made between depressive episodes that remit with alcohol abstinence ("substance-induced"), and depressive episodes that are primary and do not remit with abstinence ("independent" episodes). Additional use of other drugs may increase the risk of depression. Psychiatric disorders differ depending on gender. Women who have alcohol-use disorders often have a co-occurring psychiatric diagnosis such as major depression, anxiety, panic disorder, bulimia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or borderline personality disorder. Men with alcohol-use disorders more often have a co-occurring diagnosis of narcissistic or antisocial personality disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, impulse disorders or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Women with alcohol use disorder are more likely to experience physical or sexual assault, abuse, and domestic violence than women in the general population, which can lead to higher instances of psychiatric disorders and greater dependence on alcohol.

Social effects

Serious social problems arise from alcohol use disorder; these dilemmas are caused by the pathological changes in the brain and the intoxicating effects of alcohol. Alcohol misuse is associated with an increased risk of committing criminal offences, including child abuse, domestic violence, rape, burglary and assault. Alcoholism is associated with loss of employment, which can lead to financial problems. Drinking at inappropriate times and behavior caused by reduced judgment can lead to legal consequences, such as criminal charges for drunk driving or public disorder, or civil penalties for tortious behavior. An alcoholic's behavior and mental impairment while drunk can profoundly affect those surrounding him and lead to isolation from family and friends. This isolation can lead to marital conflict and divorce, or contribute to domestic violence. Alcoholism can also lead to child neglect, with subsequent lasting damage to the emotional development of children of people with alcohol use disorders. For this reason, children of people with alcohol use disorders can develop a number of emotional problems. For example, they can become afraid of their parents, because of their unstable mood behaviors. They may develop shame over their inadequacy to liberate their parents from alcoholism and, as a result of this, may develop self-image problems, which can lead to depression.

Alcohol withdrawal

As with similar substances with a sedative-hypnotic mechanism, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines, withdrawal from alcohol dependence can be fatal if it is not properly managed. Alcohol's primary effect is the increase in stimulation of the GABAA receptor, promoting central nervous system depression. With repeated heavy consumption of alcohol, these receptors are desensitized and reduced in number, resulting in tolerance and physical dependence. When alcohol consumption is stopped too abruptly, the person's nervous system suffers from uncontrolled synapse firing. This can result in symptoms that include anxiety, life-threatening seizures, delirium tremens, hallucinations, shakes and possible heart failure. Other neurotransmitter systems are also involved, especially dopamine, NMDA and glutamate.

Severe acute withdrawal symptoms such as delirium tremens and seizures rarely occur after 1-week post cessation of alcohol. The acute withdrawal phase can be defined as lasting between one and three weeks. In the period of 3–6 weeks following cessation, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance are common. Similar post-acute withdrawal symptoms have also been observed in animal models of alcohol dependence and withdrawal.

A kindling effect also occurs in people with alcohol use disorders whereby each subsequent withdrawal syndrome is more severe than the previous withdrawal episode; this is due to neuroadaptations which occur as a result of periods of abstinence followed by re-exposure to alcohol. Individuals who have had multiple withdrawal episodes are more likely to develop seizures and experience more severe anxiety during withdrawal from alcohol than alcohol-dependent individuals without a history of past alcohol withdrawal episodes. The kindling effect leads to persistent functional changes in brain neural circuits as well as to gene expression. Kindling also results in the intensification of psychological symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. There are decision tools and questionnaires that help guide physicians in evaluating alcohol withdrawal. For example, the CIWA-Ar objectifies alcohol withdrawal symptoms in order to guide therapy decisions which allows for an efficient interview while at the same time retaining clinical usefulness, validity, and reliability, ensuring proper care for withdrawal patients, who can be in danger of death.

Causes

A complex combination of genetic and environmental factors influences the risk of the development of alcoholism. Genes that influence the metabolism of alcohol also influence the risk of alcoholism, as can a family history of alcoholism. There is compelling evidence that alcohol use at an early age may influence the expression of genes which increase the risk of alcohol dependence. These genetic and epigenetic results are regarded as consistent with large longitudinal population studies finding that the younger the age of drinking onset, the greater the prevalence of lifetime alcohol dependence.

Severe childhood trauma is also associated with a general increase in the risk of drug dependency. Lack of peer and family support is associated with an increased risk of alcoholism developing. Genetics and adolescence are associated with an increased sensitivity to the neurotoxic effects of chronic alcohol misuse. Cortical degeneration due to the neurotoxic effects increases impulsive behaviour, which may contribute to the development, persistence and severity of alcohol use disorders. There is evidence that with abstinence, there is a reversal of at least some of the alcohol induced central nervous system damage. The use of cannabis was associated with later problems with alcohol use. Alcohol use was associated with an increased probability of later use of tobacco and illegal drugs such as cannabis.

Availability

Alcohol is the most available, widely consumed, and widely misused recreational drug. Beer alone is the world's most widely consumed alcoholic beverage; it is the third-most popular drink overall, after water and tea. It is thought by some to be the oldest fermented beverage.

Gender difference

Based on combined data in the US from SAMHSA's 2004–2005 National Surveys on Drug Use & Health, the rate of past-year alcohol dependence or misuse among persons aged 12 or older varied by level of alcohol use: 44.7% of past month heavy drinkers, 18.5% binge drinkers, 3.8% past month non-binge drinkers, and 1.3% of those who did not drink alcohol in the past month met the criteria for alcohol dependence or misuse in the past year. Males had higher rates than females for all measures of drinking in the past month: any alcohol use (57.5% vs. 45%), binge drinking (30.8% vs. 15.1%), and heavy alcohol use (10.5% vs. 3.3%), and males were twice as likely as females to have met the criteria for alcohol dependence or misuse in the past year (10.5% vs. 5.1%).

Genetic variation

There are genetic variations that affect the risk for alcoholism. Some of these variations are more common in individuals with ancestry from certain areas, for example Africa, East Asia, the Middle East and Europe. The variants with strongest effect are in genes that encode the main enzymes of alcohol metabolism, ADH1B and ALDH2. These genetic factors influence the rate at which alcohol and its initial metabolic product, acetaldehyde, are metabolized. They are found at different frequencies in people from different parts of the world. The alcohol dehydrogenase allele ADH1B*2 causes a more rapid metabolism of alcohol to acetaldehyde, and reduces risk for alcoholism; it is most common in individuals from East Asia and the Middle East. The alcohol dehydrogenase allele ADH1B*3 also causes a more rapid metabolism of alcohol. The allele ADH1B*3 is only found in some individuals of African descent and certain Native American tribes. African Americans and Native Americans with this allele have a reduced risk of developing alcoholism. Native Americans, however, have a significantly higher rate of alcoholism than average; risk factors such as cultural environmental effects (e.g. trauma) have been proposed to explain the higher rates. The aldehyde dehydrogenase allele ALDH2*2 greatly reduces the rate at which acetaldehyde, the initial product of alcohol metabolism, is removed by conversion to acetate; it greatly reduces the risk for alcoholism.

A genome-wide association study of more than 100,000 human individuals identified variants of the gene KLB, which encodes the transmembrane protein β-Klotho, as highly associated with alcohol consumption. The protein β-Klotho is an essential element in cell surface receptors for hormones involved in modulation of appetites for simple sugars and alcohol. A GWAS has found differences in the genetics of alcohol consumption and alcohol dependence, although the two are to some degree related.

Diagnosis

Definition

Misuse, problem use, abuse, and heavy use of alcohol refer to improper use of alcohol, which may cause physical, social, or moral harm to the drinker. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans defines "moderate use" as no more than two alcoholic beverages a day for men and no more than one alcoholic beverage a day for women. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as the amount of alcohol leading to a blood alcohol content (BAC) of 0.08, which, for most adults, would be reached by consuming five drinks for men or four for women over a two-hour period. According to the NIAAA, men may be at risk for alcohol-related problems if their alcohol consumption exceeds 14 standard drinks per week or 4 drinks per day, and women may be at risk if they have more than 7 standard drinks per week or 3 drinks per day. It defines a standard drink as one 12-ounce bottle of beer, one 5-ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits. Despite this risk, a 2014 report in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that only 10% of either "heavy drinkers" or "binge drinkers" defined according to the above criteria also met the criteria for alcohol dependence, while only 1.3% of non-binge drinkers met the criteria. An inference drawn from this study is that evidence-based policy strategies and clinical preventive services may effectively reduce binge drinking without requiring addiction treatment in most cases.

Alcoholism

The term alcoholism is commonly used amongst laypeople, but the word is poorly defined. Despite the imprecision inherent in the term, there have been attempts to define how the word alcoholism should be interpreted when encountered. In 1992, it was defined by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD) and ASAM as "a primary, chronic disease characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortions in thinking." MeSH has had an entry for "alcoholism" since 1999, and references the 1992 definition.

The WHO calls alcoholism "a term of long-standing use and variable meaning", and use of the term was disfavored by a 1979 WHO expert committee.

In professional and research contexts, the term "alcoholism" is not currently favored, but rather alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, or alcohol use disorder are used. Talbot (1989) observes that alcoholism in the classical disease model follows a progressive course: if a person continues to drink, their condition will worsen. This will lead to harmful consequences in their life, physically, mentally, emotionally and socially. Johnson (1980) explores the emotional progression of the addict's response to alcohol. He looks at this in four phases. The first two are considered "normal" drinking and the last two are viewed as "typical" alcoholic drinking. Johnson's four phases consist of:

- Learning the mood swing. A person is introduced to alcohol (in some cultures this can happen at a relatively young age), and the person enjoys the happy feeling it produces. At this stage, there is no emotional cost.

- Seeking the mood swing. A person will drink to regain that feeling of euphoria experienced in phase 1; the drinking will increase as more intoxication is required to achieve the same effect. Again at this stage, there are no significant consequences.

- At the third stage there are physical and social consequences, i.e., hangovers, family problems, work problems, etc. A person will continue to drink excessively, disregarding the problems.

- The fourth stage can be detrimental, as Johnson cites it as a risk for premature death. As a person now drinks to feel normal, they block out the feelings of overwhelming guilt, remorse, anxiety, and shame they experience when sober.

DSM and ICD

In the United States, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the most common diagnostic guide for substance use disorders, whereas most countries use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) for diagnostic (and other) purposes. The two manuals use similar but not identical nomenclature to classify alcohol problems.

| Manual | Nomenclature | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV | Alcohol abuse, or Alcohol dependence |

|

| DSM-5 | Alcohol use disorder | "A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by [two or more symptoms out of a total of 12], occurring within a 12-month period ...." |

| ICD-10 | Alcohol harmful use, or Alcohol dependence syndrome | Definitions are similar to that of the DSM-IV. The World Health Organization uses the term "alcohol dependence syndrome" rather than alcoholism. The concept of "harmful use" (as opposed to "abuse") was introduced in 1992's ICD-10 to minimize underreporting of damage in the absence of dependence. The term "alcoholism" was removed from ICD between ICD-8/ICDA-8 and ICD-9. |

| ICD-11 | Episode of harmful use of alcohol, Harmful pattern of use of alcohol, or Alcohol dependence |

|

Social barriers

Attitudes and social stereotypes can create barriers to the detection and treatment of alcohol use disorder. This is more of a barrier for women than men. Fear of stigmatization may lead women to deny that they are suffering from a medical condition, to hide their drinking, and to drink alone. This pattern, in turn, leads family, physicians, and others to be less likely to suspect that a woman they know has alcohol use disorder. In contrast, reduced fear of stigma may lead men to admit that they are suffering from a medical condition, to display their drinking publicly, and to drink in groups. This pattern, in turn, leads family, physicians, and others to be more likely to suspect that a man they know is someone with an alcohol use disorder.

Screening

Screening is recommended among those over the age of 18. Several tools may be used to detect a loss of control of alcohol use. These tools are mostly self-reports in questionnaire form. Another common theme is a score or tally that sums up the general severity of alcohol use.

The CAGE questionnaire, named for its four questions, is one such example that may be used to screen patients quickly in a doctor's office.

Two "yes" responses indicate that the respondent should be investigated further.

The questionnaire asks the following questions:

- Have you ever felt you needed to Cut down on your drinking?

- Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt Guilty about drinking?

- Have you ever felt you needed a drink first thing in the morning (Eye-opener) to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?

- The CAGE questionnaire has demonstrated a high effectiveness in detecting alcohol-related problems; however, it has limitations in people with less severe alcohol-related problems, white women and college students.

Other tests are sometimes used for the detection of alcohol dependence, such as the Alcohol Dependence Data Questionnaire, which is a more sensitive diagnostic test than the CAGE questionnaire. It helps distinguish a diagnosis of alcohol dependence from one of heavy alcohol use. The Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) is a screening tool for alcoholism widely used by courts to determine the appropriate sentencing for people convicted of alcohol-related offenses, driving under the influence being the most common. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a screening questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization, is unique in that it has been validated in six countries and is used internationally. Like the CAGE questionnaire, it uses a simple set of questions – a high score earning a deeper investigation. The Paddington Alcohol Test (PAT) was designed to screen for alcohol-related problems amongst those attending Accident and Emergency departments. It concords well with the AUDIT questionnaire but is administered in a fifth of the time.

Urine and blood tests

There are reliable tests for the actual use of alcohol, one common test being that of blood alcohol content (BAC). These tests do not differentiate people with alcohol use disorders from people without; however, long-term heavy drinking does have a few recognizable effects on the body, including:

- Macrocytosis (enlarged MCV)

- Elevated GGT

- Moderate elevation of AST and ALT and an AST: ALT ratio of 2:1

- High carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT)

With regard to alcoholism, BAC is useful to judge alcohol tolerance, which in turn is a sign of alcoholism. Electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities including hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, hyperuricemia, metabolic acidosis, and respiratory alkalosis are common in people with alcohol use disorders.

However, none of these blood tests for biological markers is as sensitive as screening questionnaires.

Prevention

The World Health Organization, the European Union and other regional bodies, national governments and parliaments have formed alcohol policies in order to reduce the harm of alcoholism. Increasing the age at which licit drugs that are susceptible to misuse, such as alcohol, can be purchased, and banning or restricting alcohol beverage advertising are common methods to reduce alcohol use among adolescents and young adults in particular. Credible, evidence-based educational campaigns in the mass media about the consequences of alcohol misuse have been recommended. Guidelines for parents to prevent alcohol misuse amongst adolescents, and for helping young people with mental health problems have also been suggested.

Management

Treatments are varied because there are multiple perspectives of alcoholism. Those who approach alcoholism as a medical condition or disease recommend differing treatments from, for instance, those who approach the condition as one of social choice. Most treatments focus on helping people discontinue their alcohol intake, followed up with life training and/or social support to help them resist a return to alcohol use. Since alcoholism involves multiple factors which encourage a person to continue drinking, they must all be addressed to successfully prevent a relapse. An example of this kind of treatment is detoxification followed by a combination of supportive therapy, attendance at self-help groups, and ongoing development of coping mechanisms. Much of the treatment community for alcoholism supports an abstinence-based zero tolerance approach; however, some prefer a harm-reduction approach.

Cessation of alcohol intake

Cessation of alcohol intake in individuals that have alcohol dependence is a process is often coupled with substitution of drugs, such as benzodiazepines, that have effects similar to the effects of alcohol in order to prevent alcohol withdrawal. Individuals who are only at risk of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms can be treated as outpatients. Individuals at risk of a severe withdrawal syndrome as well as those who have significant or acute comorbid conditions can be treated as inpatients. Direct treatment can be followed by a treatment program for alcohol dependence or alcohol use disorder to attempt to reduce the risk of relapse. Experiences following alcohol withdrawal, such as depressed mood and anxiety, can take weeks or months to abate while other symptoms persist longer due to persisting neuroadaptations. Alcoholism has serious adverse effects on brain function; on average it takes one year of abstinence to recover from the cognitive deficits incurred by chronic alcohol misuse.

Psychological

Various forms of group therapy or psychotherapy can be used to attempt to address underlying psychological issues that are related to alcoholism, as well as to provide relapse prevention skills. Mutual-aid group-counseling is one approach used to attempt to prevent relapse. Alcoholics Anonymous was one of the earliest organizations formed to provide mutual, nonprofessional counseling, and it is still the largest. Others include LifeRing Secular Recovery, SMART Recovery, Women for Sobriety, and Secular Organizations for Sobriety. Alcoholics Anonymous and twelve-step programs appear more effective than cognitive behavioral therapy or abstinence.

Moderate drinking

Rationing and moderation programs such as Moderation Management and DrinkWise do not mandate complete abstinence. While most people with alcohol use disorders are unable to limit their drinking in this way, some return to moderate drinking. A 2002 US study by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) showed that 17.7 percent of individuals diagnosed as alcohol dependent more than one year prior returned to low-risk drinking. This group, however, showed fewer initial symptoms of dependency.

A follow-up study, using the same subjects that were judged to be in remission in 2001–2002, examined the rates of return to problem drinking in 2004–2005. The study found abstinence from alcohol was the most stable form of remission for recovering alcoholics. There was also a 1973 study showing chronic alcoholics drinking moderately again, but a 1982 follow-up showed that 95% of subjects were not able to moderately drink over the long term. Another study was a long-term (60 year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men which concluded that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence." Internet based measures appear to be useful at least in the short term.

Medications

In the United States there are four approved medications for alcoholism: acamprosate, two methods of using naltrexone and disulfiram.

- Acamprosate may stabilise the brain chemistry that is altered due to alcohol dependence via antagonising the actions of glutamate, a neurotransmitter which is hyperactive in the post-withdrawal phase. By reducing excessive NMDA activity which occurs at the onset of alcohol withdrawal, acamprosate can reduce or prevent alcohol withdrawal related neurotoxicity. Acamprosate reduces the risk of relapse amongst alcohol-dependent persons.

- Naltrexone is a competitive antagonist for opioid receptors, effectively blocking the effects of endorphins and opioids. Naltrexone is used to decrease cravings for alcohol and encourage abstinence. Alcohol causes the body to release endorphins, which in turn release dopamine and activate the reward pathways; hence in the body Naltrexone reduces the pleasurable effects from consuming alcohol. Evidence supports a reduced risk of relapse among alcohol-dependent persons and a decrease in excessive drinking. Nalmefene also appears effective and works in a similar manner.

- The Sinclair method is another approach to using naltrexone or other opioid antagonists to treat alcoholism by having the person take the medication about an hour before they drink alcohol and only then. The medication blocks the positive reinforcement effects of ethanol and hypothetically allows the person to stop drinking or drink less.

- Disulfiram prevents the elimination of acetaldehyde, a chemical the body produces when breaking down ethanol. Acetaldehyde itself is the cause of many hangover symptoms from alcohol use. The overall effect is discomfort when alcohol is ingested: an extremely fast-acting and long-lasting, uncomfortable hangover.

Several other drugs are also used and many are under investigation.

- Benzodiazepines, while useful in the management of acute alcohol withdrawal, if used long-term can cause a worse outcome in alcoholism. Alcoholics on chronic benzodiazepines have a lower rate of achieving abstinence from alcohol than those not taking benzodiazepines. This class of drugs is commonly prescribed to alcoholics for insomnia or anxiety management. Initiating prescriptions of benzodiazepines or sedative-hypnotics in individuals in recovery has a high rate of relapse with one author reporting more than a quarter of people relapsed after being prescribed sedative-hypnotics. Those who are long-term users of benzodiazepines should not be withdrawn rapidly, as severe anxiety and panic may develop, which are known risk factors for alcohol use disorder relapse. Taper regimes of 6–12 months have been found to be the most successful, with reduced intensity of withdrawal.

- Calcium carbimide works in the same way as disulfiram; it has an advantage in that the occasional adverse effects of disulfiram, hepatotoxicity and drowsiness, do not occur with calcium carbimide.

- Ondansetron and topiramate are supported by tentative evidence in people with certain genetics. Evidence for ondansetron is more in those who have just begun having problems with alcohol. Topiramate is a derivative of the naturally occurring sugar monosaccharide D-fructose. Review articles characterize topiramate as showing "encouraging", "promising", "efficacious", and "insufficient" evidence in the treatment of alcohol use disorders.

Evidence does not support the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), antipsychotics, or gabapentin.

Dual addictions and dependences

Alcoholics may also require treatment for other psychotropic drug addictions and drug dependences. The most common dual dependence syndrome with alcohol dependence is benzodiazepine dependence, with studies showing 10–20 percent of alcohol-dependent individuals had problems of dependence and/or misuse problems of benzodiazepine drugs such as diazepam or clonazepam. These drugs are, like alcohol, depressants. Benzodiazepines may be used legally, if they are prescribed by doctors for anxiety problems or other mood disorders, or they may be purchased as illegal drugs. Benzodiazepine use increases cravings for alcohol and the volume of alcohol consumed by problem drinkers. Benzodiazepine dependency requires careful reduction in dosage to avoid benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome and other health consequences. Dependence on other sedative-hypnotics such as zolpidem and zopiclone as well as opiates and illegal drugs is common in alcoholics. Alcohol itself is a sedative-hypnotic and is cross-tolerant with other sedative-hypnotics such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines. Dependence upon and withdrawal from sedative-hypnotics can be medically severe and, as with alcohol withdrawal, there is a risk of psychosis or seizures if not properly managed.

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization estimates that as of 2016 there are 380 million people with alcoholism worldwide (5.1% of the population over 15 years of age). Substance use disorders are a major public health problem facing many countries. "The most common substance of abuse/dependence in patients presenting for treatment is alcohol." In the United Kingdom, the number of 'dependent drinkers' was calculated as over 2.8 million in 2001. About 12% of American adults have had an alcohol dependence problem at some time in their life. In the United States and Western Europe, 10 to 20 percent of men and 5 to 10 percent of women at some point in their lives will meet criteria for alcoholism. Estonia had the highest death rate from alcohol in Europe in 2015 at 8.8 per 100,000 population. In the United States, 30% of people admitted to hospital have a problem related to alcohol.

Within the medical and scientific communities, there is a broad consensus regarding alcoholism as a disease state. For example, the American Medical Association considers alcohol a drug and states that "drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use despite often devastating consequences. It results from a complex interplay of biological vulnerability, environmental exposure, and developmental factors (e.g., stage of brain maturity)." Alcoholism has a higher prevalence among men, though, in recent decades, the proportion of female alcoholics has increased. Current evidence indicates that in both men and women, alcoholism is 50–60 percent genetically determined, leaving 40–50 percent for environmental influences. Most alcoholics develop alcoholism during adolescence or young adulthood.

Prognosis

Alcoholism often reduces a person's life expectancy by around ten years. The most common cause of death in alcoholics is from cardiovascular complications. There is a high rate of suicide in chronic alcoholics, which increases the longer a person drinks. Approximately 3–15 percent of alcoholics commit suicide, and research has found that over 50 percent of all suicides are associated with alcohol or drug dependence. This is believed to be due to alcohol causing physiological distortion of brain chemistry, as well as social isolation. Suicide is also very common in adolescent alcohol abusers, with 25 percent of suicides in adolescents being related to alcohol abuse. Among those with alcohol dependence after one year, some met the criteria for low-risk drinking, even though only 25.5 percent of the group received any treatment, with the breakdown as follows: 25 percent were found to be still dependent, 27.3 percent were in partial remission (some symptoms persist), 11.8 percent asymptomatic drinkers (consumption increases chances of relapse) and 35.9 percent were fully recovered – made up of 17.7 percent low-risk drinkers plus 18.2 percent abstainers. In contrast, however, the results of a long-term (60-year) follow-up of two groups of alcoholic men indicated that "return to controlled drinking rarely persisted for much more than a decade without relapse or evolution into abstinence." There was also "return-to-controlled drinking, as reported in short-term studies, is often a mirage."

History

Historically the name "dipsomania" was coined by German physician C.W. Hufeland in 1819 before it was superseded by "alcoholism". That term now has a more specific meaning. The term "alcoholism" was first used in 1849 by the Swedish physician Magnus Huss to describe the systematic adverse effects of alcohol. Alcohol has a long history of use and misuse throughout recorded history. Biblical, Egyptian and Babylonian sources record the history of abuse and dependence on alcohol. In some ancient cultures alcohol was worshiped and in others, its misuse was condemned. Excessive alcohol misuse and drunkenness were recognized as causing social problems even thousands of years ago. However, the defining of habitual drunkenness as it was then known as and its adverse consequences were not well established medically until the 18th century. In 1647 a Greek monk named Agapios was the first to document that chronic alcohol misuse was associated with toxicity to the nervous system and body which resulted in a range of medical disorders such as seizures, paralysis, and internal bleeding. In the 1910s and 1920s, the effects of alcohol misuse and chronic drunkenness boosted membership of the temperance movement and led to the prohibition of alcohol in many Western countries, nationwide bans on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages that generally remained in place until the late 1920s or early 1930s; these policies resulted in the decline of death rates from cirrhosis and alcoholism. In 2005, alcohol dependence and misuse was estimated to cost the US economy approximately 220 billion dollars per year, more than cancer and obesity.

Society and culture

The various health problems associated with long-term alcohol consumption are generally perceived as detrimental to society, for example, money due to lost labor-hours, medical costs due to injuries due to drunkenness and organ damage from long-term use, and secondary treatment costs, such as the costs of rehabilitation facilities and detoxification centers. Alcohol use is a major contributing factor for head injuries, motor vehicle injuriess (27%), interpersonal violence (18%), suicides (18%), and epilepsy (13%). Beyond the financial costs that alcohol consumption imposes, there are also significant social costs to both the alcoholic and their family and friends. For instance, alcohol consumption by a pregnant woman can lead to an incurable and damaging condition known as fetal alcohol syndrome, which often results in cognitive deficits, mental health problems, an inability to live independently and an increased risk of criminal behaviour, all of which can cause emotional stress for parents and caregivers. Estimates of the economic costs of alcohol misuse, collected by the World Health Organization, vary from one to six percent of a country's GDP. One Australian estimate pegged alcohol's social costs at 24% of all drug misuse costs; a similar Canadian study concluded alcohol's share was 41%. One study quantified the cost to the UK of all forms of alcohol misuse in 2001 as £18.5–20 billion. All economic costs in the United States in 2006 have been estimated at $223.5 billion.

The idea of hitting rock bottom refers to an experience of stress that is attributed to alcohol misuse. There is no single definition for this idea, and people may identify their own lowest points in terms of lost jobs, lost relationships, health problems, legal problems, or other consequences of alcohol misuse. The concept is promoted by 12-step recovery groups and researchers using the transtheoretical model of motivation for behavior change. The first use of this slang phrase in the formal medical literature appeared in a 1965 review in the British Medical Journal, which said that some men refused treatment until they "hit rock bottom", but that treatment was generally more successful for "the alcohol addict who has friends and family to support him" than for impoverished and homeless addicts.

Stereotypes of alcoholics are often found in fiction and popular culture. The "town drunk" is a stock character in Western popular culture. Stereotypes of drunkenness may be based on racism or xenophobia, as in the fictional depiction of the Irish as heavy drinkers. Studies by social psychologists Stivers and Greeley attempt to document the perceived prevalence of high alcohol consumption amongst the Irish in America. Alcohol consumption is relatively similar between many European cultures, the United States, and Australia. In Asian countries that have a high gross domestic product, there is heightened drinking compared to other Asian countries, but it is nowhere near as high as it is in other countries like the United States. It is also inversely seen, with countries that have very low gross domestic product showing high alcohol consumption. In a study done on Korean immigrants in Canada, they reported alcohol was even an integral part of their meal, and is the only time solo drinking should occur. They also believe alcohol is necessary at any social event as it helps conversations start.

Peyote, a psychoactive agent, has even shown promise in treating alcoholism. Alcohol had actually replaced peyote as Native Americans’ psychoactive agent of choice in rituals when peyote was outlawed.