| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Frequent and excessive hand washing occurs in some people with OCD. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Feel the need to check things repeatedly, perform certain routines repeatedly, have certain thoughts repeatedly |

| Complications | Tics, anxiety disorder, suicide |

| Usual onset | Before 35 years |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Risk factors | Child abuse, stress |

| Diagnostic method | Based on the symptoms |

| Differential diagnosis | Anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, eating disorders, obsessive–compulsive personality disorder |

| Treatment | Counseling, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, clomipramine |

| Frequency | 2.3% |

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental and behavioral disorder in which a person has intrusive thoughts ("obsessions") and/or feels the need to perform certain routines repeatedly ("compulsions") to an extent where it induces distress or impairs one's general functioning. The condition is associated with tics, anxiety disorders, and a 10–27% risk of attempted suicide along with a general increase in suicidality.

Obsessions are unwanted and persistent thoughts, mental images or urges. These obsessions generate feelings of anxiety, disgust, or unease. Some common obsessions include—but are not limited to—fear of contamination, obsession with symmetry, and unwanted ("intrusive") thoughts about religion, sex, and/or harm.

Compulsions are repeated actions and/or routines that occur in response to obsessions. Some common compulsions include—but are not limited to—excessive hand washing or cleaning, arranging things in a particular way, performing actions according to specific rules, counting, constantly seeking reassurance, and repeatedly checking things. Many adults with this disorder are aware that these behaviors do not make sense, but they perform them anyway to achieve relief from the distress caused by obsessions. These compulsions occur to the degree that daily life is negatively affected; compulsions typically take up at least an hour of each day but, in severe cases, can fill an entire day.

The cause of OCD is unknown. There appear to be some genetic components, and it is more likely for both identical twins to be affected than both fraternal twins. Risk factors include a history of child abuse or other stress-inducing events; some cases have been documented to occur after streptococcal infections. Diagnosis is based on presented symptoms and requires ruling out other drug-related or medical causes, and rating scales such as the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) can be used to assess severity. Other disorders with similar symptoms include generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, eating disorders, tic disorders, and obsessive–compulsive personality disorder.

Without treatment, OCD often lasts decades. Treatment may involve psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); pharmacotherapy using antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or clomipramine; deep brain stimulation (DBS); or any combination of these. CBT for OCD involves increasing exposure to fears and obsessions while preventing the compulsive behavior that would normally accompany obsessions. Contrary to this, metacognitive therapy encourages ritual behaviors in order to alter the relationship to one's thoughts about them. In treating OCD pharmacologically, SSRIs/SNRIs are significantly more effective when used in excess of the usual dosage for depression; however, higher doses may be accompanied by an increase in side-effect burden. Commonly used SSRIs include sertraline, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram. Commonly used SNRIs include venlafaxine and duloxetine. Some patients may have a treatment-resistant (or "treatment-refractory") case of OCD, in which they fail to improve after taking the maximum tolerated dose of multiple SSRIs/SNRIs for at least two months; in such cases, second-line treatment is necessary. The second-line treatments for OCD include clomipramine and antipsychotic augmentation, both of which are associated with more intensive side effects and are therefore not used as primary pharmacological treatments. In the most severe and/or treatment-resistant cases, DBS is used; this type of therapy has shown promising results, but it is still considered experimental due to the limited literature surrounding its methods, success rates, and side effects.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder affects about 2.3% of people at some point in their lives, while rates during any given year are about 1.2%. It is unusual for symptoms to begin after the age of 35, and around 50% of patients experience negative effects to daily life before the age of 20. Males and females are affected about equally, and OCD occurs worldwide. The phrase "obsessive–compulsive" is sometimes used in an informal manner unrelated to OCD to describe someone as being excessively meticulous, perfectionistic, absorbed, or otherwise fixated.

Signs and symptoms

OCD can present with a wide variety of symptoms. Certain groups of symptoms usually occur together; these groups are sometimes viewed as dimensions (or "clusters") that may reflect an underlying process. The standard assessment tool for OCD, the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), has 13 predefined categories of symptoms. These symptoms fit into three to five groupings. A meta-analytic review of symptom structures found a four-factor structure (grouping) to be most reliable. The observed groups included a "symmetry factor," a "forbidden thoughts factor," a "cleaning factor," and a "hoarding factor." The "symmetry factor" correlated highly with obsessions related to ordering, counting, and symmetry, as well as repeating compulsions. The "forbidden thoughts factor" correlated highly with intrusive and distressing thoughts of a violent, religious, or sexual nature. The "cleaning factor" correlated highly with obsessions about contamination and compulsions related to cleaning. The "hoarding factor" only involved hoarding-related obsessions and compulsions and was identified as being distinct from other symptom groupings.

Some OCD subtypes have been associated with improvement in performance on certain tasks, such as pattern recognition (washing subtype) and spatial working memory (obsessive thought subtype). Subgroups have also been distinguished by neuroimaging findings and treatment response. Neuroimaging studies on this have been too few, and the subtypes examined have differed too much to draw any conclusions. On the other hand, subtype-dependent treatment response has been studied, and the hoarding subtype has consistently responded least to treatment.

While OCD is considered a homogeneous disorder from a neuropsychological perspective, many of the putative neuropsychological deficits may be the result of comorbid disorders. For example, adults with OCD have exhibited more symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than adults without OCD.

Obsessions

Obsessions are stress-inducing thoughts that recur and persist despite efforts to ignore or confront them. People with OCD frequently perform tasks, or compulsions, to seek relief from obsession-related anxiety. Within and among individuals, initial obsessions vary in clarity and vividness. A relatively vague obsession could involve a general sense of disarray or tension accompanied by a belief that life cannot proceed as normal while the imbalance remains. A more intense obsession could be a preoccupation with the thought or image of a close family member or friend dying or intrusions related to "relationship rightness." Other obsessions concern the possibility that someone or something other than oneself—such as God, the devil, or disease—will harm either the affected individual or the people or things about which the affected individual cares. Others with OCD may experience the sensation of invisible protrusions emanating from their bodies or feel that inanimate objects are ensouled.

Some people with OCD experience sexual obsessions that may involve intrusive thoughts or images of "kissing, touching, fondling, oral sex, anal sex, intercourse, incest, and rape" with "strangers, acquaintances, parents, children, family members, friends, coworkers, animals and religious figures," and can include heterosexual or homosexual contact with people of any age. Similar to other intrusive thoughts or images, some disquieting sexual thoughts are normal at times, but people with OCD may attach extraordinary significance to such thoughts. For example, obsessive fears about sexual orientation can appear to the affected individual, and even to those around them, as a crisis of sexual identity. Furthermore, the doubt that accompanies OCD leads to uncertainty regarding whether one might act on the troubling thoughts, resulting in self-criticism or self-loathing.

Most people with OCD understand that their thoughts do not correspond with reality; however, they feel that they must act as though these ideas are correct or realistic. For example, someone who engages in compulsive hoarding might be inclined to treat inorganic matter as if it had the sentience or rights of living organisms, despite accepting that such behavior is irrational on an intellectual level. There is a debate as to whether hoarding should be considered with other OCD symptoms.

Compulsions

Some people with OCD perform compulsive rituals because they inexplicably feel that they must do so, while others act compulsively to mitigate the anxiety that stems from obsessive thoughts. The affected individual might feel that these actions will either prevent a dreaded event from occurring or push the event from their thoughts. In any case, their reasoning is so idiosyncratic or distorted that it results in significant distress, either personally or for those around the affected individual. Excessive skin picking, hair pulling, nail biting, and other body-focused repetitive behavior disorders are all on the obsessive–compulsive spectrum. Some individuals with OCD are aware that their behaviors are not rational, but they feel compelled to follow through with them to fend off feelings of panic or dread. Furthermore, compulsions often stem from memory distrust, a symptom of OCD characterized by insecurity in one's skills in perception, attention, and memory, even in cases where there is no clear evidence of a deficit.

Common compulsions may include hand washing, cleaning, checking things (such as locks on doors), repeating actions (such as turning on and off switches), ordering items in a certain way, and requesting reassurance. Although some people perform actions repeatedly, they do not necessarily perform these actions compulsively; for example, morning or nighttime routines and religious practices are not compulsions. Whether behaviors qualify as compulsions or mere habit depends on the context in which they are performed. For instance, arranging and ordering books for eight hours a day would be expected of someone who works in a library, but this routine would seem abnormal in other situations. In other words, habits tend to bring efficiency to one's life, while compulsions tend to disrupt it. Furthermore, compulsions are different from tics (such as touching, tapping, rubbing, or blinking) and stereotyped movements (such as head banging, body rocking, or self-biting), which are usually not as complex and not precipitated by obsessions. It can sometimes be difficult to tell the difference between compulsions and complex tics, and about 10–40% of people with OCD also have a lifetime tic disorder.

People with OCD rely on compulsions as an escape from their obsessive thoughts; however, they are aware that relief is only temporary, and that intrusive thoughts will return. Some affected individuals use compulsions to avoid situations that may trigger obsessions. Compulsions may be actions directly related to the obsession, such as someone obsessed with contamination compulsively washing their hands, but they can be unrelated as well. In addition to experiencing the anxiety and fear that typically accompanies OCD, affected individuals may spend hours performing compulsions every day. In such situations, it can become difficult for the person to fulfill their work, familial, or social roles. These behaviors can also cause adverse physical symptoms; for example, people who obsessively wash their hands with antibacterial soap and hot water can make their skin red and raw with dermatitis.

Individuals with OCD often use rationalizations to explain their behavior; however, these rationalizations do not apply to the behavioral pattern but to each individual occurrence. For example, someone compulsively checking the front door may argue that the time and stress associated with one check is less than the time and stress associated with being robbed, and checking is consequently the better option. This reasoning often occurs in a cyclical manner and can continue for as long as the affected person needs it to in order to feel safe.

In cognitive behavioral therapy, OCD patients are asked to overcome intrusive thoughts by not indulging in any compulsions. They are taught that rituals keep OCD strong, while not performing them causes OCD to become weaker. This position is supported by the pattern of memory distrust; the more often compulsions are repeated, the more weakened memory trust becomes, and this cycle continues because memory distrust increases compulsion frequency. For body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRB) such as trichotillomania (hair pulling), skin picking, and onychophagia (nail biting), behavioral interventions such as habit reversal training and decoupling are recommended for the treatment of compulsive behaviors.

OCD sometimes manifests without overt compulsions, which may be termed "primarily obsessional OCD." OCD without overt compulsions could, by one estimate, characterize as many as 50–60% of OCD cases.

Insight and overvalued ideation

The DSM-V identifies a continuum for the level of insight in OCD, ranging from "good" insight (the least severe) to no insight (the most severe). "Good" or "fair" insight is characterized by the acknowledgment that obsessive-compulsive beliefs are or may not be true; "poor" insight, in the middle of the continuum, is characterized by the belief that obsessive-compulsive beliefs are probably true. The absence of insight altogether, in which the individual is completely convinced that their beliefs are true, is also identified as a delusional thought pattern and occurs in about 4% of people with OCD.When cases of OCD with no insight become severe, affected individuals have an unshakable belief in the reality of their delusions, which can make their cases difficult to differentiate from psychotic disorders.

Some people with OCD exhibit what is known as "overvalued ideas," ideas that are abnormal compared to affected individuals' respective cultures and more treatment-resistant than most negative thoughts and obsessions. After some discussion, it is possible to convince the individual that their fears are unfounded. It may be more difficult to practice ERP therapy on such people because they may be unwilling to cooperate, at least initially. Similar to how insight is identified on a continuum, obsessive-compulsive beliefs are characterized on a spectrum ranging from obsessive doubt to delusional conviction. In the United States, overvalued ideation (OVI) is considered most akin to "poor" insight—especially when considering belief strength as one of an idea's key identifiers—but European qualifications have historically been broader. Furthermore, severe and frequent overvalued ideas are considered similar to "idealized values," which are so rigidly held by and so important to affected individuals that they end up becoming a defining identity. In adolescent OCD patients, OVI is considered a severe symptom.

Historically, OVI has been thought to be linked to poorer treatment outcome in patients with OCD, but it is currently considered a poor indicator of prognosis. The Overvalued Ideas Scale (OVIS) has been developed as a reliable quantitative method of measuring levels of OVI in patients with OCD, and research has suggested that overvalued ideas are more stable for those with more extreme OVIS scores.

Cognitive performance

Though OCD was once believed to be associated with above-average intelligence, this does not appear to necessarily be the case. A 2013 review reported that people with OCD may sometimes have mild but wide-ranging cognitive deficits, most significantly those affecting spatial memory and to a lesser extent with verbal memory, fluency, executive function and processing speed, while auditory attention was not significantly affected. People with OCD show impairment in formulating an organizational strategy for coding information, set-shifting and motor and cognitive inhibition.

Specific subtypes of symptom dimensions in OCD have been associated with specific cognitive deficits. For example, the results of one meta-analysis comparing washing and checking symptoms reported that washers outperformed checkers on eight out of ten cognitive tests. The symptom dimension of contamination and cleaning may be associated with higher scores on tests of inhibition and verbal memory.

Children

Approximately 1–2% of children are affected by OCD. Obsessive–compulsive disorder symptoms tend to develop more frequently in children 10–14 years of age, with males displaying symptoms at an earlier age and at a more severe level than do females. In children, symptoms can be grouped into at least four types.

Associated conditions

People with OCD may be diagnosed with other conditions as well as, or instead of, OCD, such as obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, social anxiety disorder, bulimia nervosa, Tourette syndrome, transformation obsession, ASD, ADHD, dermatillomania (compulsive skin picking), body dysmorphic disorder and trichotillomania (hair pulling). More than 50% of people with OCD experience suicidal tendencies, and 15% have attempted suicide. Depression, anxiety and prior suicide attempts increase the risk of future suicide attempts.

Individuals with OCD have also been found to be affected by delayed sleep phase syndrome at a substantially higher rate than is the general public. Moreover, severe OCD symptoms are consistently associated with greater sleep disturbance. Reduced total sleep time and sleep efficiency have been observed in people with OCD, with delayed sleep onset and offset and an increased prevalence of delayed sleep phase disorder.

Some research has demonstrated a link between drug addiction and OCD. For example, there is a higher risk of drug addiction among those with any anxiety disorder (possibly as a way of coping with the heightened levels of anxiety), but drug addiction among people with OCD may serve as a type of compulsive behavior and not just as a coping mechanism. Depression is also extremely prevalent among people with OCD. One explanation for the high depression rate among OCD populations was posited by Mineka, Watson and Clark (1998), who explained that people with OCD (or any other anxiety disorder) may feel depressed because of an "out of control" type of feeling.

Someone exhibiting OCD signs does not necessarily have OCD. Behaviors that present as (or seem to be) obsessive or compulsive can also be found in a number of other conditions, including obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD), ASD, or disorders in which perseveration is a possible feature (ADHD, PTSD, bodily disorders or habit problems), or subclinically.

Some with OCD present with features typically associated with Tourette syndrome, such as compulsions that may appear to resemble motor tics; this has been termed "tic-related OCD" or "Tourettic OCD".

OCD frequently occurs comorbidly with both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Between 60 and 80% of those with OCD experience a major depressive episode in their lifetime. Comorbidity rates have been reported at between 19 and 90% because of methodological differences. Between 9–35% of those with bipolar disorder also have OCD, compared to 1–2% in the general population. About 50% of those with OCD experience cyclothymic traits or hypomanic episodes. OCD is also associated with anxiety disorders. Lifetime comorbidity for OCD has been reported at 22% for specific phobia, 18% for social anxiety disorder, 12% for panic disorder, and 30% for generalized anxiety disorder. The comorbidity rate for OCD and ADHD has been reported to be as high as 51%.

Causes

The cause is unknown. Both environmental and genetic factors are believed to play a role. Risk factors include a history of child abuse or other stress-inducing event.

Drug-induced OCD

Many different types of medication can create/induce OCD in patients without previous symptoms. A new chapter about OCD in the DSM-5 (2013) now specifically includes drug-induced OCD.

Atypical antipsychotics (second-generation antipsychotics) such as olanzapine (Zyprexa) have been proven to induce de novo OCD in patients.

Genetics

There appear to be some genetic components with identical twins more often affected than non-identical twins. Further, individuals with OCD are more likely to have first-degree family members exhibiting the same disorders than do matched controls. In cases in which OCD develops during childhood, there is a much stronger familial link in the disorder than with cases in which OCD develops later in adulthood. In general, genetic factors account for 45–65% of the variability in OCD symptoms in children diagnosed with the disorder. A 2007 study found evidence supporting the possibility of a heritable risk for OCD.

A mutation has been found in the human serotonin transporter gene hSERT in unrelated families with OCD.

A systematic review found that while neither allele was associated with OCD overall, in Caucasians the L allele was associated with OCD. Another meta-analysis observed an increased risk in those with the homozygous S allele, but found the LS genotype to be inversely associated with OCD.

A genome-wide association study found OCD to be linked with SNPs near BTBD3 and two SNPs in DLGAP1 in a trio-based analysis, but no SNP reached significance when analyzed with case-control data.

One meta-analysis found a small but significant association between a polymorphism in SLC1A1 and OCD.

The relationship between OCD and COMT has been inconsistent, with one meta-analysis reporting a significant association, albeit only in men, and another meta analysis reporting no association.

It has been postulated by evolutionary psychologists that moderate versions of compulsive behavior may have had evolutionary advantages. Examples would be moderate constant checking of hygiene, the hearth or the environment for enemies. Similarly, hoarding may have had evolutionary advantages. In this view, OCD may be the extreme statistical "tail" of such behaviors, possibly the result of a high number of predisposing genes.

Autoimmune

A controversial hypothesis is that some cases of rapid onset of OCD in children and adolescents may be caused by a syndrome connected to Group A streptococcal infections known as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). OCD and tic disorders are hypothesized to arise in a subset of children as a result of a post-streptococcal autoimmune process. The PANDAS hypothesis is unconfirmed and unsupported by data, and two new categories have been proposed: PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome) and CANS (childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndrome). The CANS/PANS hypotheses include different possible mechanisms underlying acute-onset neuropsychiatric conditions, but do not exclude GABHS infections as a cause in a subset of individuals. PANDAS, PANS and CANS are the focus of clinical and laboratory research but remain unproven. Whether PANDAS is a distinct entity differing from other cases of tic disorders or OCD is debated.

A review of studies examining anti-basal ganglia antibodies in OCD found an increased risk of having anti-basal ganglia antibodies in those with OCD versus the general population.

Mechanisms

Neuroimaging

Functional neuroimaging during symptom provocation has observed abnormal activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, right premotor cortex, left superior temporal gyrus, globus pallidus externus, hippocampus and right uncus. Weaker foci of abnormal activity were found in the left caudate, posterior cingulate cortex and superior parietal lobule. However, an older meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging in OCD reported that the only consistent functional neuroimaging finding was increased activity in the orbital gyrus and head of the caudate nucleus, while ACC activation abnormalities were too inconsistent. A meta-analysis comparing affective and nonaffective tasks observed differences with controls in regions implicated in salience, habit, goal-directed behavior, self-referential thinking and cognitive control. For nonaffective tasks, hyperactivity was observed in the insula, ACC, and head of the caudate/putamen, while hypoactivity was observed in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and posterior caudate. Affective tasks were observed to relate to increased activation in the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), while decreased activation was found in the pallidum, ventral anterior thalamus and posterior caudate. The involvement of the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical loop in OCD as well as the high rates of comorbidity between OCD and ADHD have led some to draw a link in their mechanism. Observed similarities include dysfunction of the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex, as well as shared deficits in executive functions. The involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in OCD is shared with bipolar disorder and may explain the high degree of comorbidity. Decreased volumes of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex related to executive function has also been observed in OCD.

People with OCD evince increased grey matter volumes in bilateral lenticular nuclei, extending to the caudate nuclei, with decreased grey matter volumes in bilateral dorsal medial frontal/anterior cingulate gyri. These findings contrast with those in people with other anxiety disorders, who evince decreased (rather than increased) grey matter volumes in bilateral lenticular/caudate nuclei, as well as decreased grey matter volumes in bilateral dorsal medial frontal/anterior cingulate gyri. Increased white matter volume and decreased fractional anisotropy in anterior midline tracts has been observed in OCD, possibly indicating increased fiber crossings.

Cognitive models

Generally two categories of models for OCD have been postulated, the first involving deficits in executive function, and the second involving deficits in modulatory control. The first category of executive dysfunction is based on the observed structural and functional abnormalities in the dlPFC, striatum and thalamus. The second category involving dysfunctional modulatory control primarily relies on observed functional and structural differences in the ACC, mPFC and OFC.

One proposed model suggests that dysfunction in the OFC leads to improper valuation of behaviors and decreased behavioral control, while the observed alterations in amygdala activations leads to exaggerated fears and representations of negative stimuli.

Because of the heterogeneity of OCD symptoms, studies differentiating various symptoms have been performed. Symptom-specific neuroimaging abnormalities include the hyperactivity of caudate and ACC in checking rituals, while finding increased activity of cortical and cerebellar regions in contamination-related symptoms. Neuroimaging differentiating content of intrusive thoughts has found differences between aggressive as opposed to taboo thoughts, finding increased connectivity of the amygdala, ventral striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in aggressive symptoms while observing increased connectivity between the ventral striatum and insula in sexual/religious intrusive thoughts.

Another model proposes that affective dysregulation links excessive reliance on habit-based action selection with compulsions. This is supported by the observation that those with OCD demonstrate decreased activation of the ventral striatum when anticipating monetary reward, as well as increased functional connectivity between the VS and the OFC. Furthermore, those with OCD demonstrate reduced performance in Pavlovian fear-extinction tasks, hyperresponsiveness in the amygdala to fearful stimuli, and hyporesponsiveness in the amygdala when exposed to positively valanced stimuli. Stimulation of the nucleus accumbens has also been observed to effectively alleviate both obsessions and compulsions, supporting the role of affective dysregulation in generating both.

Neurobiological

From the observation of the efficacy of antidepressants in OCD, a serotonin hypothesis of OCD has been formulated. Studies of peripheral markers of serotonin, as well as challenges with proserotonergic compounds have yielded inconsistent results, including evidence pointing towards basal hyperactivity of serotonergic systems. Serotonin receptor and transporter binding studies have yielded conflicting results, including higher and lower serotonin receptor 5-HT2A and serotonin transporter binding potentials that were normalized by treatment with SSRIs. Despite inconsistencies in the types of abnormalities found, evidence points towards dysfunction of serotonergic systems in OCD. Orbitofrontal cortex overactivity is attenuated in people who have successfully responded to SSRI medication, a result believed to be caused by increased stimulation of serotonin receptors 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C.

A complex relationship between dopamine and OCD has been observed. Although antipsychotics, which act by antagonizing dopamine receptors may improve some cases of OCD, they frequently exacerbate others. Antipsychotics, in the low doses used to treat OCD, may actually increase the release of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex, through inhibiting autoreceptors. Further complicating things is the efficacy of amphetamines, decreased dopamine transporter activity observed in OCD, and low levels of D2 binding in the striatum. Furthermore, increased dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens after deep brain stimulation correlates with improvement in symptoms, pointing to reduced dopamine release in the striatum playing a role in generating symptoms.

Abnormalities in glutamatergic neurotransmission have implicated in OCD. Findings such as increased cerebrospinal glutamate, less consistent abnormalities observed in neuroimaging studies and the efficacy of some glutamatergic drugs such as the glutamate-inhibiting riluzole have implicated glutamate in OCD. OCD has been associated with reduced N-Acetylaspartic acid in the mPFC, which is thought to reflect neuron density or functionality, although the exact interpretation has not been established.

Diagnosis

Formal diagnosis may be performed by a psychologist, psychiatrist, clinical social worker, or other licensed mental health professional. To be diagnosed with OCD, a person must have obsessions, compulsions, or both, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The Quick Reference to the 2000 edition of the DSM states that several features characterize clinically significant obsessions and compulsions, and that such obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses or images that are experienced as intrusive and that cause marked anxiety or distress. These thoughts, impulses or images are of a degree or type that lies outside the normal range of worries about conventional problems. A person may attempt to ignore or suppress such obsessions, or to neutralize them with some other thought or action, and will tend to recognize the obsessions as idiosyncratic or irrational.

Compulsions become clinically significant when a person feels driven to perform them in response to an obsession, or according to rules that must be applied rigidly, and when the person consequently feels or causes significant distress. Therefore, while many people who do not suffer from OCD may perform actions often associated with OCD (such as ordering items in a pantry by height), the distinction with clinically significant OCD lies in the fact that the person who suffers from OCD must perform these actions to avoid significant psychological distress. These behaviors or mental acts are aimed at preventing or reducing distress or preventing some dreaded event or situation; however, these activities are not logically or practically connected to the issue, or they are excessive. In addition, at some point during the course of the disorder, the individual must realize that his or her obsessions or compulsions are unreasonable or excessive.

Moreover, the obsessions or compulsions must be time-consuming (taking up more than one hour per day) or cause impairment in social, occupational or scholastic functioning. It is helpful to quantify the severity of symptoms and impairment before and during treatment for OCD. In addition to the person's estimate of the time spent each day harboring obsessive-compulsive thoughts or behaviors, concrete tools can be used to gauge the person's condition. This may be done with rating scales, such as the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; expert rating) or the obsessive-compulsive inventory (OCI-R; self-rating). With measurements such as these, psychiatric consultation can be more appropriately determined because it has been standardized.

OCD is sometimes placed in a group of disorders called the obsessive–compulsive spectrum.

Differential diagnosis

OCD is often confused with the separate condition obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD). OCD is egodystonic, meaning that the disorder is incompatible with the sufferer's self-concept. Because egodystonic disorders go against a person's self-concept, they tend to cause much distress. OCPD, on the other hand, is egosyntonic—marked by the person's acceptance that the characteristics and behaviours displayed as a result are compatible with their self-image, or are otherwise appropriate, correct or reasonable.

As a result, people with OCD are often aware that their behavior is not rational and are unhappy about their obsessions but nevertheless feel compelled by them. By contrast, people with OCPD are not aware of anything abnormal; they will readily explain why their actions are rational. It is usually impossible to convince them otherwise, and they tend to derive pleasure from their obsessions or compulsions.

Management

A form of psychotherapy called "cognitive behavioral therapy" (CBT) and psychotropic medications are first-line treatments for OCD. Other forms of psychotherapy, such as psychodynamics and psychoanalysis may help in managing some aspects of the disorder, but in 2007 the American Psychiatric Association (APA) noted a lack of controlled studies showing their effectiveness "in dealing with the core symptoms of OCD".

Therapy

The specific technique used in CBT is called exposure and response prevention (ERP), which involves teaching the person to deliberately come into contact with the situations that trigger the obsessive thoughts and fears ("exposure") without carrying out the usual compulsive acts associated with the obsession ("response prevention"), thus gradually learning to tolerate the discomfort and anxiety associated with not performing the ritualistic behavior. At first, for example, someone might touch something only very mildly "contaminated" (such as a tissue that has been touched by another tissue that has been touched by the end of a toothpick that has touched a book that came from a "contaminated" location, such as a school). That is the "exposure". The "ritual prevention" is not washing. Another example might be leaving the house and checking the lock only once (exposure) without going back and checking again (ritual prevention). The person fairly quickly habituates to the anxiety-producing situation and discovers that his or her anxiety level drops considerably; he or she can then progress to touching something more "contaminated" or not checking the lock at all—again, without performing the ritual behavior of washing or checking.

ERP has a strong evidence base, and it is considered the most effective treatment for OCD. However, this claim was doubted by some researchers in 2000, who criticized the quality of many studies. A 2007 Cochrane review also found that psychological interventions derived from CBT models were more effective than treatment as usual consisting of no treatment, waiting list or non-CBT interventions. For body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRB), behavioral interventions are recommended by reviews such as habit-reversal training and decoupling.

Psychotherapy in combination with psychiatric medication may be more effective than either option alone for individuals with severe OCD.

Medication

The medications most frequently used are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Clomipramine, a medication belonging to the class of tricyclic antidepressants, appears to work as well as SSRIs but has a higher rate of side effects.

SSRIs are a second-line treatment of adult obsessive compulsive disorder with mild functional impairment and as first-line treatment for those with moderate or severe impairment. In children, SSRIs can be considered as a second-line therapy in those with moderate to severe impairment, with close monitoring for psychiatric adverse effects. SSRIs are efficacious in the treatment of OCD; people treated with SSRIs are about twice as likely to respond to treatment as are those treated with placebo. Efficacy has been demonstrated both in short-term (6–24 weeks) treatment trials and in discontinuation trials with durations of 28–52 weeks.

In 2006, the National Institute of Clinical and Health Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommended antipsychotics for OCD that does not improve with SSRI treatment. For OCD there is tentative evidence for risperidone and insufficient evidence for olanzapine. Quetiapine is no better than placebo with regard to primary outcomes, but small effects were found in terms of YBOCS score. The efficacy of quetiapine and olanzapine are limited by an insufficient number of studies. A 2014 review article found two studies that indicated that aripiprazole was "effective in the short-term" and found that "[t]here was a small effect-size for risperidone or anti-psychotics in general in the short-term"; however, the study authors found "no evidence for the effectiveness of quetiapine or olanzapine in comparison to placebo." While quetiapine may be useful when used in addition to an SSRI in treatment-resistant OCD, these drugs are often poorly tolerated, and have metabolic side effects that limit their use. None of the atypical antipsychotics appear to be useful when used alone. Another review reported that no evidence supports the use of first-generation antipsychotics in OCD.

A guideline by the APA suggested that dextroamphetamine may be considered by itself after more well-supported treatments have been tried.

Procedures

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been found to have effectiveness in some severe and refractory cases.

Surgery may be used as a last resort in people who do not improve with other treatments. In this procedure, a surgical lesion is made in an area of the brain (the cingulate cortex). In one study, 30% of participants benefitted significantly from this procedure. Deep brain stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation are possible surgical options that do not require destruction of brain tissue. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration approved deep-brain stimulation for the treatment of OCD under a humanitarian device exemption requiring that the procedure be performed only in a hospital with special qualifications to do so.

In the United States, psychosurgery for OCD is a treatment of last resort and will not be performed until the person has failed several attempts at medication (at the full dosage) with augmentation, and many months of intensive cognitive–behavioral therapy with exposure and ritual/response prevention. Likewise, in the United Kingdom, psychosurgery cannot be performed unless a course of treatment from a suitably qualified cognitive–behavioral therapist has been carried out.

Children

Therapeutic treatment may be effective in reducing ritual behaviors of OCD for children and adolescents. Similar to the treatment of adults with OCD, CBT stands as an effective and validated first line of treatment of OCD in children. Family involvement, in the form of behavioral observations and reports, is a key component to the success of such treatments. Parental interventions also provide positive reinforcement for a child who exhibits appropriate behaviors as alternatives to compulsive responses. In a recent meta-analysis of evidenced-based treatment of OCD in children, family-focused individual CBT was labeled as "probably efficacious", establishing it as one of the leading psychosocial treatments for youth with OCD. After one or two years of therapy, in which a child learns the nature of his or her obsession and acquires strategies for coping, that child may acquire a larger circle of friends, exhibit less shyness, and become less self-critical.

Although the causes of OCD in younger age groups range from brain abnormalities to psychological preoccupations, life stress such as bullying and traumatic familial deaths may also contribute to childhood cases of OCD, and acknowledging these stressors can play a role in treating the disorder.

Epidemiology

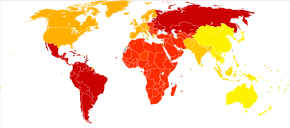

Obsessive–compulsive disorder affects about 2.3% of people at some point in their life, with the yearly rate about 1.2%. OCD occurs worldwide. It is unusual for symptoms to begin after the age of 35 and half of people develop problems before 20. Males and females are affected about equally.

Prognosis

Quality of life is reduced across all domains in OCD. While psychological or pharmacological treatment can lead to a reduction of OCD symptoms and an increase in reported quality of life, symptoms may persist at moderate levels even following adequate treatment courses, and completely symptom-free periods are uncommon. In pediatric OCD, around 40% still have the disorder in adulthood, and around 40% qualify for remission.

History

In the 7th century AD, John Climacus records an instance of a young monk plagued by constant and overwhelming "temptations to blasphemy" consulting an older monk, who told him, "My son, I take upon myself all the sins which these temptations have led you, or may lead you, to commit. All I require of you is that for the future you pay no attention to them whatsoever." The Cloud of Unknowing, a Christian mystical text from the late 14th century, recommends dealing with recurring obsessions by first attempting to ignore them, and, if that fails, "cower under them like a poor wretch and a coward overcome in battle, and reckon it to be a waste of your time for you to strive any longer against them", a technique now known as "emotional flooding".

From the 14th to the 16th century in Europe, it was believed that people who experienced blasphemous, sexual or other obsessive thoughts were possessed by the devil. Based on this reasoning, treatment involved banishing the "evil" from the "possessed" person through exorcism. The vast majority of people who thought that they were possessed by the devil did not suffer from hallucinations or other "spectacular symptoms", but "complained of anxiety, religious fears, and evil thoughts." In 1584, a woman from Kent, England, named Mrs. Davie, described by a justice of the peace as "a good wife", was nearly burned at the stake after she confessed that she experienced constant, unwanted urges to murder her family.

The English term obsessive-compulsive arose as a translation of German Zwangsvorstellung ('obsession') used in the first conceptions of OCD by Carl Westphal. Westphal's description went on to influence Pierre Janet, who further documented features of OCD. In the early 1910s, Sigmund Freud attributed obsessive–compulsive behavior to unconscious conflicts that manifest as symptoms. Freud describes the clinical history of a typical case of "touching phobia" as starting in early childhood, when the person has a strong desire to touch an item. In response, the person develops an "external prohibition" against this type of touching. However, this "prohibition does not succeed in abolishing" the desire to touch; all it can do is repress the desire and "force it into the unconscious." Freudian psychoanalysis remained the dominant treatment for OCD until the mid-1980s, even though medicinal and therapeutic treatments were known and available, because it was widely thought that these treatments would be detrimental to the effectiveness of the psychotherapy. In the mid-1980s, this approach changed and practitioners began treating OCD primarily with medicine and practical therapy rather than through psychoanalysis.

Notable cases

John Bunyan (1628–1688), the author of The Pilgrim's Progress, displayed symptoms of OCD (which had not yet been named). During the most severe period of his condition, he would mutter the same phrase over and over again to himself while rocking back and forth. He later described his obsessions in his autobiography Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, stating, "These things may seem ridiculous to others, even as ridiculous as they were in themselves, but to me they were the most tormenting cogitations." He wrote two pamphlets advising those suffering from similar anxieties. In one of them, he warns against indulging in compulsions: "Have care of putting off your trouble of spirit in the wrong way: by promising to reform yourself and lead a new life, by your performances or duties".

British poet, essayist and lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) also suffered from OCD.: 54–55 He had elaborate rituals for crossing the thresholds of doorways, and repeatedly walked up and down staircases counting the steps. He would touch every post on the street as he walked past, only step in the middles of paving stones, and repeatedly perform tasks as though they had not been done properly the first time.

The American aviator and filmmaker Howard Hughes is known to have had OCD. Friends of Hughes have also mentioned his obsession with minor flaws in clothing. This was conveyed in The Aviator (2004), a film biography of Hughes.

English singer-songwriter George Ezra has openly spoken about his life-long struggle with OCD, particularly "Pure OCD".

American actor James Spader is also known to suffer from OCD.

Society and culture

Art, entertainment and media

Movies and television shows may portray idealized or incomplete representations of disorders such as OCD. Compassionate and accurate literary and on-screen depictions may help counteract the potential stigma associated with an OCD diagnosis, and lead to increased public awareness, understanding and sympathy for such disorders.

- In the film As Good as It Gets (1997), actor Jack Nicholson portrays a man with OCD who performs ritualistic behaviors that disrupt his life.

- The film Matchstick Men (2003), directed by Ridley Scott, portrays a con man named Roy (Nicolas Cage) with OCD who opens and closes doors three times while counting aloud before he can walk through them.

- In the television series Monk (2002–2009), the titular character Adrian Monk fears both human contact and dirt.

- In Turtles All the Way Down (2017), a young adult novel by author John Green, teenage main character Aza Holmes struggles with OCD that manifests as a fear of the human microbiome. Throughout the story, Aza repeatedly opens an unhealed callus on her finger to drain out what she believes are pathogens. The novel is based on Green's own experiences with OCD. He explained that Turtles All the Way Down is intended to show how "most people with chronic mental illnesses also live long, fulfilling lives".

- The British TV series Pure (2019) stars Charly Clive as a 24-year-old Marnie who is plagued by disturbing sexual thoughts, as a kind of primarily obsessional obsessive compulsive disorder. The series is based on a book of the same name by Rose Cartwright.

Research

The naturally occurring sugar inositol has been suggested as a treatment for OCD.

μ-Opioids, such as hydrocodone and tramadol, may improve OCD symptoms. Administration of opiate treatment may be contraindicated in individuals concurrently taking CYP2D6 inhibitors such as fluoxetine and paroxetine.

Much current research is devoted to the therapeutic potential of the agents that affect the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate or the binding to its receptors. These include riluzole, memantine, gabapentin, N-acetylcysteine, topiramate and lamotrigine.