From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Computational creativity (also known as artificial creativity, mechanical creativity, creative computing or creative computation) is a multidisciplinary endeavour that is located at the intersection of the fields of artificial intelligence, cognitive psychology, philosophy, and the arts.

The goal of computational creativity is to model, simulate or

replicate creativity using a computer, to achieve one of several ends:

- To construct a program or computer capable of human-level creativity.

- To better understand human creativity and to formulate an algorithmic perspective on creative behavior in humans.

- To design programs that can enhance human creativity without necessarily being creative themselves.

The field of computational creativity concerns itself with

theoretical and practical issues in the study of creativity. Theoretical

work on the nature and proper definition of creativity is performed in

parallel with practical work on the implementation of systems that

exhibit creativity, with one strand of work informing the other.

The applied form of computational creativity is known as media synthesis.

Theoretical issues

If

eminent creativity is about rule-breaking or the disavowal of

convention, how is it possible for an algorithmic system to be creative?

In essence, this is a variant of Ada Lovelace's objection to machine intelligence, as recapitulated by modern theorists such as Teresa Amabile. If a machine can do only what it was programmed to do, how can its behavior ever be called creative?

Indeed, not all computer theorists would agree with the premise that computers can only do what they are programmed to do—a key point in favor of computational creativity.

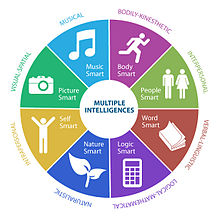

Defining creativity in computational terms

Because

no single perspective or definition seems to offer a complete picture

of creativity, the AI researchers Newell, Shaw and Simon

developed the combination of novelty and usefulness into the

cornerstone of a multi-pronged view of creativity, one that uses the

following four criteria to categorize a given answer or solution as

creative:

- The answer is novel and useful (either for the individual or for society)

- The answer demands that we reject ideas we had previously accepted

- The answer results from intense motivation and persistence

- The answer comes from clarifying a problem that was originally vague

Whereas the above reflects a "top-down" approach to computational

creativity, an alternative thread has developed among "bottom-up"

computational psychologists involved in artificial neural network

research. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, for example, such

generative neural systems were driven by genetic algorithms. Experiments involving recurrent nets were successful in hybridizing simple musical melodies and predicting listener expectations.

In his book, Superhuman Creators, Al Byrd argues that the primary

source of creativity in humans and other animals is affordance

awareness – awareness of the action possibilities in an environment.

Superhuman creativity can be achieved by increasing the affordance

awareness of artificial entities dramatically, and integrating that

awareness tightly with the systems capable of capitalizing on the action

possibilities.

Artificial neural networks

Before 1989, artificial neural networks

have been used to model certain aspects of creativity. Peter Todd

(1989) first trained a neural network to reproduce musical melodies from

a training set of musical pieces. Then he used a change algorithm to

modify the network's input parameters. The network was able to randomly

generate new music in a highly uncontrolled manner. In 1992, Todd

extended this work, using the so-called distal teacher approach that had been developed by

Paul Munro, Paul Werbos, D. Nguyen and Bernard Widrow, Michael I. Jordan and David Rumelhart.

In the new approach there are two neural networks, one of which is

supplying training patterns to another.

In later efforts by Todd, a composer would select a set of melodies that

define the melody space, position them on a 2-d plane with a

mouse-based graphic interface, and train a connectionist network to

produce those melodies, and listen to the new "interpolated" melodies

that the network generates corresponding to intermediate points in the

2-d plane.

Key concepts from the literature

Some high-level and philosophical themes recur throughout the field of computational creativity.

Important categories of creativity

Margaret Boden refers to creativity that is novel merely to the agent that produces it as "P-creativity" (or "psychological creativity"), and refers to creativity that is recognized as novel by society at large

as "H-creativity" (or "historical creativity"). Stephen Thaler has

suggested a new category he calls "V-" or "Visceral creativity" wherein

significance is invented through neural mapping to raw sensory inputs to

a Creativity Machine architecture, with the "gateway" nets perturbed to

produce alternative interpretations, and downstream nets shifting such

interpretations to fit the overarching context.

An important variety of such V-creativity is consciousness itself,

wherein meaning is reflexively invented to activation turnover within

the brain. Value driven creativity gives more freedom and autonomy to the AI system.

Exploratory and transformational creativity

Boden

also distinguishes between the creativity that arises from an

exploration within an established conceptual space, and the creativity

that arises from a deliberate transformation or transcendence of this

space. She labels the former as exploratory creativity and the latter as transformational creativity,

seeing the latter as a form of creativity far more radical,

challenging, and rarer than the former. Following the criteria from

Newell and Simon elaborated above, we can see that both forms of

creativity should produce results that are appreciably novel and useful

(criterion 1), but exploratory creativity is more likely to arise from a

thorough and persistent search of a well-understood space (criterion 3)

-- while transformational creativity should involve the rejection of

some of the constraints that define this space (criterion 2) or some of

the assumptions that define the problem itself (criterion 4). Boden's

insights have guided work in computational creativity at a very general

level, providing more an inspirational touchstone for development work

than a technical framework of algorithmic substance. However, Boden's

insights are more recently also the subject of formalization, most

notably in the work by Geraint Wiggins.

Generation and evaluation

The

criterion that creative products should be novel and useful means that

creative computational systems are typically structured into two phases,

generation and evaluation. In the first phase, novel (to the system

itself, thus P-Creative) constructs are generated; unoriginal

constructs that are already known to the system are filtered at this

stage. This body of potentially creative constructs is then evaluated,

to determine which are meaningful and useful and which are not. This

two-phase structure conforms to the Geneplore model of Finke, Ward and

Smith, which is a psychological model of creative generation based on empirical observation of human creativity.

Combinatorial creativity

A great deal, perhaps all, of human creativity can be understood as a novel combination of pre-existing ideas or objects. Common strategies for combinatorial creativity include:

- Placing a familiar object in an unfamiliar setting (e.g., Marcel Duchamp's Fountain) or an unfamiliar object in a familiar setting (e.g., a fish-out-of-water story such as The Beverly Hillbillies)

- Blending two superficially different objects or genres (e.g., a sci-fi story set in the Wild West, with robot cowboys, as in Westworld, or the reverse, as in Firefly; Japanese haiku poems, etc.)

- Comparing a familiar object to a superficially unrelated and semantically distant concept (e.g., "Makeup is the Western burka"; "A zoo is a gallery with living exhibits")

- Adding a new and unexpected feature to an existing concept (e.g., adding a scalpel to a Swiss Army knife; adding a camera to a mobile phone)

- Compressing two incongruous scenarios into the same narrative to get a joke (e.g., the Emo Philips joke "Women are always using men to advance their careers. Damned anthropologists!")

- Using an iconic image from one domain in a domain for an unrelated or incongruous idea or product (e.g., using the Marlboro Man image to sell cars, or to advertise the dangers of smoking-related impotence).

The combinatorial perspective allows us to model creativity as a

search process through the space of possible combinations. The

combinations can arise from composition or concatenation of different

representations, or through a rule-based or stochastic transformation of

initial and intermediate representations. Genetic algorithms and neural networks can be used to generate blended or crossover representations that capture a combination of different inputs.

Conceptual blending

Mark Turner and Gilles Fauconnier propose a model called Conceptual Integration Networks that elaborates upon Arthur Koestler's ideas about creativity as well as more recent work by Lakoff and Johnson, by synthesizing ideas from Cognitive Linguistic research into mental spaces and conceptual metaphors. Their basic model defines an integration network as four connected spaces:

- A first input space (contains one conceptual structure or mental space)

- A second input space (to be blended with the first input)

- A generic space of stock conventions and image-schemas that allow the input spaces to be understood from an integrated perspective

- A blend space in which a selected projection of elements from

both input spaces are combined; inferences arising from this

combination also reside here, sometimes leading to emergent structures

that conflict with the inputs.

Fauconnier and Turner describe a collection of optimality principles

that are claimed to guide the construction of a well-formed integration

network. In essence, they see blending as a compression mechanism in

which two or more input structures are compressed into a single blend

structure. This compression operates on the level of conceptual

relations. For example, a series of similarity relations between the

input spaces can be compressed into a single identity relationship in

the blend.

Some computational success has been achieved with the blending

model by extending pre-existing computational models of analogical

mapping that are compatible by virtue of their emphasis on connected

semantic structures. More recently, Francisco Câmara Pereira presented an implementation of blending theory that employs ideas both from GOFAI and genetic algorithms

to realize some aspects of blending theory in a practical form; his

example domains range from the linguistic to the visual, and the latter

most notably includes the creation of mythical monsters by combining 3-D

graphical models.

Linguistic creativity

Language provides continuous opportunity for creativity, evident in the generation of novel sentences, phrasings, puns, neologisms, rhymes, allusions, sarcasm, irony, similes, metaphors, analogies, witticisms, and jokes. Native speakers of morphologically rich languages frequently create new word-forms that are easily understood, and some have found their way to the dictionary. The area of natural language generation

has been well studied, but these creative aspects of everyday language

have yet to be incorporated with any robustness or scale.

Hypothesis of creative patterns

In

the seminal work of applied linguist Ronald Carter, he hypothesized two

main creativity types involving words and word patterns:

pattern-reforming creativity, and pattern-forming creativity.

Pattern-reforming creativity refers to creativity by the breaking of

rules, reforming and reshaping patterns of language often through

individual innovation, while pattern-forming creativity refers to

creativity via conformity to language rules rather than breaking them,

creating convergence, symmetry and greater mutuality between

interlocutors through their interactions in the form of repetitions.

Story generation

Substantial

work has been conducted in this area of linguistic creation since the

1970s, with the development of James Meehan's TALE-SPIN

[31]

system. TALE-SPIN viewed stories as narrative descriptions of a

problem-solving effort, and created stories by first establishing a goal

for the story's characters so that their search for a solution could be

tracked and recorded. The MINSTREL

system represents a complex elaboration of this basic approach,

distinguishing a range of character-level goals in the story from a

range of author-level goals for the story. Systems like Bringsjord's

BRUTUS

elaborate these ideas further to create stories with complex

inter-personal themes like betrayal. Nonetheless, MINSTREL explicitly

models the creative process with a set of Transform Recall Adapt Methods

(TRAMs) to create novel scenes from old. The MEXICA

model of Rafael Pérez y Pérez and Mike Sharples is more explicitly

interested in the creative process of storytelling, and implements a

version of the engagement-reflection cognitive model of creative

writing.

The company Narrative Science

makes computer generated news and reports commercially available,

including summarizing team sporting events based on statistical data

from the game. It also creates financial reports and real estate

analyses.

Metaphor and simile

Example of a metaphor: "She was an ape."

Example of a simile: "Felt like a tiger-fur blanket."

The computational study of these phenomena has mainly focused on

interpretation as a knowledge-based process. Computationalists such as Yorick Wilks, James Martin, Dan Fass, John Barnden,

and Mark Lee have developed knowledge-based approaches to the

processing of metaphors, either at a linguistic level or a logical

level. Tony Veale and Yanfen Hao have developed a system, called

Sardonicus, that acquires a comprehensive database of explicit similes

from the web; these similes are then tagged as bona-fide (e.g., "as hard

as steel") or ironic (e.g., "as hairy as a bowling ball", "as pleasant as a root canal");

similes of either type can be retrieved on demand for any given

adjective. They use these similes as the basis of an on-line metaphor

generation system called Aristotle

that can suggest lexical metaphors for a given descriptive goal (e.g.,

to describe a supermodel as skinny, the source terms "pencil", "whip", "whippet", "rope", "stick-insect" and "snake" are suggested).

Analogy

The

process of analogical reasoning has been studied from both a mapping and

a retrieval perspective, the latter being key to the generation of

novel analogies. The dominant school of research, as advanced by Dedre Gentner, views analogy as a structure-preserving process; this view has been implemented in the structure mapping engine or SME, the MAC/FAC retrieval engine (Many Are Called, Few Are Chosen), ACME (Analogical Constraint Mapping Engine) and ARCS (Analogical Retrieval Constraint System). Other mapping-based approaches include Sapper,

which situates the mapping process in a semantic-network model of

memory. Analogy is a very active sub-area of creative computation and

creative cognition; active figures in this sub-area include Douglas Hofstadter, Paul Thagard, and Keith Holyoak. Also worthy of note here is Peter Turney and Michael Littman's machine learning approach to the solving of SAT-style

analogy problems; their approach achieves a score that compares well

with average scores achieved by humans on these tests.

Joke generation

Humour is an especially knowledge-hungry process, and the most

successful joke-generation systems to date have focussed on

pun-generation, as exemplified by the work of Kim Binsted and Graeme

Ritchie. This work includes the JAPE

system, which can generate a wide range of puns that are consistently

evaluated as novel and humorous by young children. An improved version

of JAPE has been developed in the guise of the STANDUP system, which has

been experimentally deployed as a means of enhancing linguistic

interaction with children with communication disabilities. Some limited

progress has been made in generating humour that involves other aspects

of natural language, such as the deliberate misunderstanding of

pronominal reference (in the work of Hans Wim Tinholt and Anton

Nijholt), as well as in the generation of humorous acronyms in the

HAHAcronym system of Oliviero Stock and Carlo Strapparava.

Neologism

The

blending of multiple word forms is a dominant force for new word

creation in language; these new words are commonly called "blends" or "portmanteau words" (after Lewis Carroll). Tony Veale has developed a system called ZeitGeist that harvests neological headwords from Wikipedia and interprets them relative to their local context in Wikipedia and relative to specific word senses in WordNet.

ZeitGeist has been extended to generate neologisms of its own; the

approach combines elements from an inventory of word parts that are

harvested from WordNet, and simultaneously determines likely glosses for

these new words (e.g., "food traveller" for "gastronaut" and "time

traveller" for "chrononaut"). It then uses Web search

to determine which glosses are meaningful and which neologisms have not

been used before; this search identifies the subset of generated words

that are both novel ("H-creative") and useful.

A corpus linguistic approach to the search and extraction of neologism have also shown to be possible. Using Corpus of Contemporary American English as a reference corpus, Locky Law has performed an extraction of neologism, portmanteaus and slang words using the hapax legomena which appeared in the scripts of American TV drama House M.D.

In terms of linguistic research in neologism, Stefan Th. Gries

has performed a quantitative analysis of blend structure in English and

found that "the degree of recognizability of the source words and that

the similarity of source words to the blend plays a vital role in blend

formation." The results were validated through a comparison of

intentional blends to speech-error blends.

Poetry

More than iron, more than lead, more than gold I need electricity.

I need it more than I need lamb or pork or lettuce or cucumber.

I need it for my dreams.

Racter,

from The Policeman's Beard Is Half Constructed

Like jokes, poems involve a complex interaction of different

constraints, and no general-purpose poem generator adequately combines

the meaning, phrasing, structure and rhyme aspects of poetry.

Nonetheless, Pablo Gervás has developed a noteworthy system called ASPERA that employs a case-based reasoning

(CBR) approach to generating poetic formulations of a given input text

via a composition of poetic fragments that are retrieved from a

case-base of existing poems. Each poem fragment in the ASPERA case-base

is annotated with a prose string that expresses the meaning of the

fragment, and this prose string is used as the retrieval key for each

fragment. Metrical rules are then used to combine these fragments into a well-formed poetic structure. Racter is an example of such a software project.

Musical creativity

Computational creativity in the music domain has focused both on the

generation of musical scores for use by human musicians, and on the

generation of music for performance by computers. The domain of

generation has included classical music (with software that generates

music in the style of Mozart and Bach) and jazz. Most notably, David Cope has written a software system called "Experiments in Musical Intelligence" (or "EMI")

that is capable of analyzing and generalizing from existing music by a

human composer to generate novel musical compositions in the same

style. EMI's output is convincing enough to persuade human listeners

that its music is human-generated to a high level of competence.

In the field of contemporary classical music, Iamus is the first computer that composes from scratch, and produces final scores that professional interpreters can play. The London Symphony Orchestra played a piece for full orchestra, included in Iamus' debut CD, which New Scientist described as "The first major work composed by a computer and performed by a full orchestra". Melomics, the technology behind Iamus, is able to generate pieces in different styles of music with a similar level of quality.

Creativity research in jazz has focused on the process of

improvisation and the cognitive demands that this places on a musical

agent: reasoning about time, remembering and conceptualizing what has

already been played, and planning ahead for what might be played next.

The robot Shimon, developed by Gil Weinberg of Georgia Tech, has demonstrated jazz improvisation.

Virtual improvisation software based on researches on stylistic

modeling carried out by Gerard Assayag and Shlomo Dubnov include OMax,

SoMax and PyOracle, are used to create improvisations in real-time by

re-injecting variable length sequences learned on the fly from live

performer.

In 1994, a Creativity Machine architecture (see above) was able

to generate 11,000 musical hooks by training a synaptically perturbed

neural net on 100 melodies that had appeared on the top ten list over

the last 30 years. In 1996, a self-bootstrapping Creativity Machine

observed audience facial expressions through an advanced machine vision

system and perfected its musical talents to generate an album entitled

"Song of the Neurons"

In the field of musical composition, the patented works by René-Louis Baron

allowed to make a robot that can create and play a multitude of

orchestrated melodies so-called "coherent" in any musical style. All

outdoor physical parameter associated with one or more specific musical

parameters, can influence and develop each of these songs (in real time

while listening to the song). The patented invention Medal-Composer raises problems of copyright.

Visual and artistic creativity

Computational

creativity in the generation of visual art has had some notable

successes in the creation of both abstract art and representational art.

The most famous program in this domain is Harold Cohen's AARON,

which has been continuously developed and augmented since 1973. Though

formulaic, Aaron exhibits a range of outputs, generating black-and-white

drawings or colour paintings that incorporate human figures (such as

dancers), potted plants, rocks, and other elements of background

imagery. These images are of a sufficiently high quality to be displayed

in reputable galleries.

Other software artists of note include the NEvAr system (for "Neuro-Evolutionary Art") of Penousal Machado.

NEvAr uses a genetic algorithm to derive a mathematical function that

is then used to generate a coloured three-dimensional surface. A human

user is allowed to select the best pictures after each phase of the

genetic algorithm, and these preferences are used to guide successive

phases, thereby pushing NEvAr's search into pockets of the search space

that are considered most appealing to the user.

The Painting Fool, developed by Simon Colton

originated as a system for overpainting digital images of a given scene

in a choice of different painting styles, colour palettes and brush

types. Given its dependence on an input source image to work with, the

earliest iterations of the Painting Fool raised questions about the

extent of, or lack of, creativity in a computational art system.

Nonetheless, in more recent work, The Painting Fool has been extended to

create novel images, much as AARON

does, from its own limited imagination. Images in this vein include

cityscapes and forests, which are generated by a process of constraint satisfaction

from some basic scenarios provided by the user (e.g., these scenarios

allow the system to infer that objects closer to the viewing plane

should be larger and more color-saturated, while those further away

should be less saturated and appear smaller). Artistically, the images

now created by the Painting Fool appear on a par with those created by

Aaron, though the extensible mechanisms employed by the former

(constraint satisfaction, etc.) may well allow it to develop into a more

elaborate and sophisticated painter.

The artist Krasi Dimtch (Krasimira Dimtchevska) and the software

developer Svillen Ranev have created a computational system combining a

rule-based generator of English sentences and a visual composition

builder that converts sentences generated by the system into abstract

art.

The software generates automatically indefinite number of different

images using different color, shape and size palettes. The software also

allows the user to select the subject of the generated sentences or/and

the one or more of the palettes used by the visual composition builder.

An emerging area of computational creativity is that of video

games. ANGELINA is a system for creatively developing video games in

Java by Michael Cook. One important aspect is Mechanic Miner, a system

that can generate short segments of code that act as simple game

mechanics.

ANGELINA can evaluate these mechanics for usefulness by playing simple

unsolvable game levels and testing to see if the new mechanic makes the

level solvable. Sometimes Mechanic Miner discovers bugs in the code and

exploits these to make new mechanics for the player to solve problems

with.

In July 2015 Google released DeepDream – an open source

computer vision program, created to detect faces and other patterns in

images with the aim of automatically classifying images, which uses a

convolutional neural network to find and enhance patterns in images via

algorithmic pareidolia, thus creating a dreamlike psychedelic appearance in the deliberately over-processed images.

In August 2015 researchers from Tübingen, Germany

created a convolutional neural network that uses neural representations

to separate and recombine content and style of arbitrary images which

is able to turn images into stylistic imitations of works of art by

artists such as a Picasso or Van Gogh in about an hour. Their algorithm is put into use in the website DeepArt that allows users to create unique artistic images by their algorithm.

In early 2016, a global team of researchers explained how a new

computational creativity approach known as the Digital Synaptic Neural

Substrate (DSNS) could be used to generate original chess puzzles that

were not derived from endgame databases.

The DSNS is able to combine features of different objects (e.g. chess

problems, paintings, music) using stochastic methods in order to derive

new feature specifications which can be used to generate objects in any

of the original domains. The generated chess puzzles have also been

featured on YouTube.

Creativity in problem solving

Creativity is also useful in allowing for unusual solutions in problem solving. In psychology and cognitive science, this research area is called creative problem solving. The Explicit-Implicit Interaction (EII) theory of creativity has recently been implemented using a CLARION-based computational model that allows for the simulation of incubation and insight in problem solving. The emphasis of this computational creativity project is not on performance per se (as in artificial intelligence

projects) but rather on the explanation of the psychological processes

leading to human creativity and the reproduction of data collected in

psychology experiments. So far, this project has been successful in

providing an explanation for incubation effects in simple memory

experiments, insight in problem solving, and reproducing the

overshadowing effect in problem solving.

Debate about "general" theories of creativity

Some

researchers feel that creativity is a complex phenomenon whose study is

further complicated by the plasticity of the language we use to

describe it. We can describe not just the agent of creativity as

"creative" but also the product and the method. Consequently, it could

be claimed that it is unrealistic to speak of a general theory of creativity.

Nonetheless, some generative principles are more general than others,

leading some advocates to claim that certain computational approaches

are "general theories". Stephen Thaler, for instance, proposes that

certain modalities of neural networks are generative enough, and general

enough, to manifest a high degree of creative capabilities.

Criticism of Computational Creativity

Traditional computers, as mainly used in the computational creativity

application, do not support creativity, as they fundamentally transform

a set of discrete, limited domain of input parameters into a set of

discrete, limited domain of output parameters using a limited set of

computational functions.

As such, a computer cannot be creative, as everything in the output

must have been already present in the input data or the algorithms.

For some related discussions and references to related work are

captured in some recent work on philosophical foundations of simulation.

Mathematically, the same set of arguments against creativity has been made by Chaitin.

Similar observations come from a Model Theory perspective. All this

criticism emphasizes that computational creativity is useful and may

look like creativity, but it is not real creativity, as nothing new is

created, just transformed in well defined algorithms.

Events

The

International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC) occurs

annually, organized by The Association for Computational Creativity. Events in the series include:

- ICCC 2018, Salamanca, Spain

- ICCC 2017, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

- ICCC 2016, Paris, France

- ICCC 2015, Park City, Utah, USA. Keynote: Emily Short

- ICCC 2014, Ljubljana, Slovenia. Keynote: Oliver Deussen

- ICCC 2013, Sydney, Australia. Keynote: Arne Dietrich

- ICCC 2012, Dublin, Ireland. Keynote: Steven Smith

- ICCC 2011, Mexico City, Mexico. Keynote: George E Lewis

- ICCC 2010, Lisbon, Portugal. Keynote/Invited Talks: Nancy J Nersessian and Mary Lou Maher

Previously, the community of computational creativity has held a

dedicated workshop, the International Joint Workshop on Computational

Creativity, every year since 1999. Previous events in this series

include:

- IJWCC 2003, Acapulco, Mexico, as part of IJCAI'2003

- IJWCC 2004, Madrid, Spain, as part of ECCBR'2004

- IJWCC 2005, Edinburgh, UK, as part of IJCAI'2005

- IJWCC 2006, Riva del Garda, Italy, as part of ECAI'2006

- IJWCC 2007, London, UK, a stand-alone event

- IJWCC 2008, Madrid, Spain, a stand-alone event

The 1st Conference on Computer Simulation of Musical Creativity will be held

- CCSMC 2016, 17–19 June, University of Huddersfield, UK. Keynotes: Geraint Wiggins and Graeme Bailey.

Publications and forums

Design

Computing and Cognition is one conference that addresses computational

creativity. The ACM Creativity and Cognition conference is another forum

for issues related to computational creativity. Journées d'Informatique

Musicale 2016 keynote by Shlomo Dubnov was on Information Theoretic

Creativity.

A number of recent books provide either a good introduction or a

good overview of the field of Computational Creativity. These include:

- Pereira, F. C. (2007). "Creativity and Artificial Intelligence: A

Conceptual Blending Approach". Applications of Cognitive Linguistics

series, Mouton de Gruyter.

- Veale, T. (2012). "Exploding the Creativity Myth: The

Computational Foundations of Linguistic Creativity". Bloomsbury

Academic, London.

- McCormack, J. and d'Inverno, M. (eds.) (2012). "Computers and Creativity". Springer, Berlin.

- Veale, T., Feyaerts, K. and Forceville, C. (2013, forthcoming).

"Creativity and the Agile Mind: A Multidisciplinary study of a

Multifaceted phenomenon". Mouton de Gruyter.

In addition to the proceedings of conferences and workshops, the

computational creativity community has thus far produced these special

journal issues dedicated to the topic:

- New Generation Computing, volume 24, issue 3, 2006

- Journal of Knowledge-Based Systems, volume 19, issue 7, November 2006

- AI Magazine, volume 30, number 3, Fall 2009

- Minds and Machines, volume 20, number 4, November 2010

- Cognitive Computation, volume 4, issue 3, September 2012

- AIEDAM, volume 27, number 4, Fall 2013

- Computers in Entertainment, two special issues on Music Meta-Creation (MuMe), Fall 2016 (forthcoming)

In addition to these, a new journal has started which focuses on computational creativity within the field of music.

- JCMS 2016, Journal of Creative Music Systems