The evil eye (Greek: μάτι, mati; Turkish: Nazar; Hebrew: עַיִן הָרָע; Italian: malocchio; Arabic: عين الحسد, ayn; Persian: چشم cheshm) is a supernatural belief in curse, brought about by a malevolent glare, usually given to a person when one is unaware. It dates back at least to Greek classical antiquity, 6th century BC where it appeared on Chalcidian drinking vessels, known as 'eye-cups', as a type of apotropaic magic. It is found in many cultures in the Mediterranean region, with such cultures often believing that receiving the evil eye will cause misfortune or injury, while others believe it to be a kind of supernatural force that casts or reflects a malevolent gaze back-upon those who wish harm upon others (especially innocents). Older iterations of the symbol were often made of ceramic or clay; however, following the production of glass beads in the Mediterranean region in approximately 1500 BC, evil eye beads were popularised with the Phoenicians, Persians, Greeks, Romans and Ottomans. Blue was likely used as it was relatively easy to create; however, modern evil eyes can be a range of colors.

The idea expressed by the term causes many different cultures to pursue protective measures against it, with around 40% of the world's population believing in the evil eye. The concept and its significance vary widely among different cultures, but it is especially prominent in the Mediterranean and West Asia. The idea appears multiple times in Jewish rabbinic literature. Other popular amulets and talismans used to ward off the evil eye include the hamsa, while Italy (especially Southern Italy) employs a variety of other unique charms and gestures to defend against the evil eye, including the cornicello, the cimaruta, and the sign of the horns.

While the Egyptian Eye of Horus is a similar symbol of protection and good health, the Greek evil eye talisman specifically protects against malevolent gazes. Similarly, the Eye-Idols (c. 8700–3500 BC) excavated at the Tell Brak Eye Temple are believed to have been figurines offered to the gods, and according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are unrelated to a belief in the evil eye.

History

Belief in the evil eye dates back to at least Ancient Ugarit, as it is attested to in texts from this city (ruins in modern-day Syria). Given that the city was destroyed circa 1250BC, during the late Bronze Age collapse to never be rebuilt, the belief dates back at least to this point, and likely earlier. Later in Greek Classical antiquity, it is referenced by Hesiod, Callimachus, Plato, Diodorus Siculus, Theocritus, Plutarch, Heliodorus, Pliny the Elder, and Aulus Gellius. Peter Walcot's Envy and the Greeks (1978) listed more than one hundred works by these and other authors mentioning the evil eye. Noting that Greeks are an ethnic group indigenous to Greece and the Levant, artefacts can be found from this region.

Classical authors attempted both to describe and to explain the function of the evil eye. Plutarch's scientific explanation stated that the eyes were the chief, if not sole, source of the deadly rays that were supposed to spring up like poisoned darts from the inner recesses of a person possessing the evil eye. Plutarch treated the phenomenon of the evil eye as something seemingly inexplicable that is a source of wonder and cause of incredulity. Pliny the Elder described the ability of certain African enchanters to have the "power of fascination with the eyes and can even kill those on whom they fix their gaze".

The idea of the evil eye appears in the poetry of Virgil in a conversation between the shepherds Menalcas and Damoetas. In the passage, Menalcas is lamenting the poor health of his stock: "What eye is it that has fascinated my tender lambs?".

Protection from the eye

The belief in the evil eye during antiquity varied across different regions and periods. The evil eye was not feared with equal intensity in every corner of the Roman Empire. There were places in which people felt more conscious of the danger of the evil eye. In Roman times, not only were individuals considered to possess the power of the evil eye but whole tribes, especially those of Pontus and Scythia, were believed to be transmitters of the evil eye.

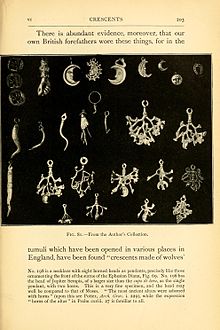

The phallic charm called fascinum in Latin, from the verb fascinare, "to cast a spell" (the origin of the English word "fascinate") is one example of an apotropaic object used against the evil eye. They have been found throughout Europe and into the Middle East from contexts dating from the first century BC to the fourth century AD. The phallic charms were often objects of personal adornment (such as pendants and finger rings), but also appeared as stone carvings on buildings, mosaics, and wind-chimes (tintinnabula). Examples of stone phallic carvings, such as from Leptis Magna, depict a disembodied phallus attacking an evil eye by ejaculating towards it.

In describing their ability to deflect the evil eye, Ralph Merrifield described the Roman phallic charm as a "kind of lightning conductor for good luck".

Around the world

Belief in the evil eye is strongest in West Asia, Latin America, East and West Africa, Central America, South Asia, Central Asia, and Europe, especially the Mediterranean region; it has also spread to areas, including northern Europe, particularly in the Celtic regions, and the Americas, where it was brought by European colonists and West Asian immigrants.

Belief in the evil eye is found in the Islamic doctrine, based upon the statement of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, "The influence of an evil eye is a fact..." [Sahih Muslim, Book 26, Number 5427]. Authentic practices of warding off the evil eye are also commonly practiced by Muslims: rather than directly expressing appreciation of, for example, a child's beauty, it is customary to say Masha'Allah, that is, "God has willed it", or invoking God's blessings upon the object or person that is being admired. A number of beliefs about the evil eye are also found in folk religion, typically revolving around the use of amulets or talismans as a means of protection.

In the Aegean Region and other areas where light-colored eyes are relatively rare, people with green eyes, and especially blue eyes, are thought to bestow the curse, intentionally or unintentionally. Thus, in Greece and Turkey amulets against the evil eye take the form of eyes looking back at someone, and in the painting by John Phillip, we witness the culture-clash experienced by a woman who suspects that the artist's gaze implies that he is looking at her with the evil eye.

Among those who do not take the evil eye literally, either by reason of the culture in which they were raised or because they simply do not believe it, the phrase, "to give someone the evil eye" usually means simply to glare at the person in anger or disgust. The term has entered into common usage within the English language. Within the broadcasting industry, it refers to when a presenter signals to the interviewee or co-presenter to stop talking due to a shortage of time.

Protective talismans and cures

Attempts to ward off the curse of the evil eye have resulted in a number of talismans in many cultures. As a class, they are called "apotropaic" (Greek for "prophylactic" / προφυλακτικός or "protective", literally: "turns away") talismans, meaning that they turn away or turn back harm.

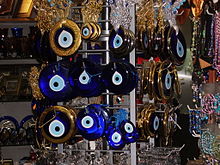

Disks or balls, consisting of concentric blue and white circles (usually, from inside to outside, dark blue, light blue, white, and dark blue) representing an evil eye are common apotropaic talismans in West Asia, found on the prows of Mediterranean boats and elsewhere; in some forms of the folklore, the staring eyes are supposed to bend the malicious gaze back to the sorcerer.

Known as nazar (Turkish: nazar boncuğu or nazarlık), this talisman is most frequently seen in Turkey, found in or on houses and vehicles or worn as beads

The hamsa hand, an apotropaic hand-shaped talisman against the evil eye, is found in West Asia. The word hamsa, also spelled khamsa and hamesh, means "five" referring to the fingers of the hand. In Jewish culture, the hamsa is called the Hand of Miriam; in some Muslim cultures, the Hand of Fatima. Though condemned as superstition by doctrinaire Muslims, it is almost exclusively among Muslims in the Near East and Mediterranean that the belief in envious looks containing destructive power or the talismanic power of a nazar to defend against them. To adherents of other faiths in the region, the nazar is an attractive decoration

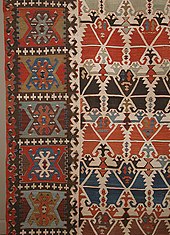

A variety of motifs to ward off the evil eye are commonly woven into tribal kilim rugs. Such motifs include a cross (Turkish: Haç) to divide the evil eye into four, a hook (Turkish: Çengel) to destroy the evil eye, or a human eye (Turkish: Göz) to avert the evil gaze. The shape of a lucky amulet (Turkish: Muska; often, a triangular package containing a sacred verse) is often woven into kilims for the same reason.

In Islam

In Islam, the evil eye, or al-’ayn العين, also عين الحسودة), is a common belief that individuals have the power to cause harm to people, animals or objects, by looking at them in a way that indicates jealousy. Although envy activates the evil eye, this happens (or usually happens) unconsciously, and the person who casts it is not responsible (or usually not responsible) for it. In addition to being looked at, astrology may play a part. Someone may become a victim of the evil eye by virtue of an "unfavorable celestial configuration" at the time of victim's birth, "according to some scholars".

Among the rituals to ward off the evil eye are to say "TabarakAllah" (تبارك الله) ("Blessings of God") or "Masha'Allah" (ما شاء الله) ("God has willed it") if a compliment is to be made. Reciting Sura Ikhlas, Sura Al-Falaq and Sura Al-Nas from the Qur'an, three times after Fajr and after Maghrib is also used as a means of personal protection against the evil eye.

To cure the evil eye, strict orthodox (Salafi) scholars prescribe only "ritual bathing and by pious incantations" (the same Islamic cure for other supernatural maladies), according to scholar Remke Kruk. According to Salafi scholars, the Quran and Hadith call for performing exorcism using the words of God or his names, reciting in Arabic or in a language which can be understood by the people. While some Musliims avail themselves of magic practices -- talismans, amulets, fortune-tellers or asking jinns to help -- these are forbidden (haram) according to the strictly orthodox. According to another source, some scholars believe using talismans (along with the Quran) is permissible.

In Judaism

The evil eye is mentioned several times in the classic Pirkei Avot (Ethics of Our Fathers). In Chapter II, five disciples of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakai give advice on how to follow the good path in life and avoid the bad. Rabbi Eliezer says an evil eye is worse than a bad friend, a bad neighbor, or an evil heart.

Talmudic exegete, Rashi, says in the wake of the words of Israel's Sages that when the ten sons of Jacob went down into Egypt to buy provisions, they made themselves inconspicuous by each entering into a separate gate, so that they would not be gazed upon by the local Egyptians and, thereby, trigger a malevolent response (the Evil eye) by their onlookers, seeing that they were all handsome and of brave and manly dispositions.

Some Jews believe that a "good eye" designates an attitude of goodwill and kindness towards others. Someone who has this attitude in life will rejoice when his fellow man prospers; he will wish everyone well. An "evil eye" denotes the opposite attitude. A man with "an evil eye" will not only feel no joy but experience actual distress when others prosper and will rejoice when others suffer. A person of this character represents a great danger to our moral purity, according to some Jews.

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook explained that the evil eye is "an example of how one soul may affect another through unseen connections between them. We are all influenced by our environment... The evil eye is the venomous impact from malignant feelings of jealousy and envy of those around us."

Many observant Jews avoid talking about valuable items they own, good luck that has come to them and, in particular, their children. If any of these are mentioned, the speaker and/or listener will say b'li ayin hara (Hebrew), meaning "without an evil eye", or kein eina hara (Yiddish; often shortened to kennahara), "no evil eye". Another way to ward off the evil eye is to spit three times (or pretend to). Romans call this custom "despuere malum," to spit at evil. It has also been suggested the 10th Commandment: "Do not covet anything that belongs to your neighbor" is a law against bestowing the evil eye on another person.

Caribbean/West Indies

In Trinidad and Tobago, the evil eye is called maljo (from French mal yeux, meaning 'bad eye'). The term is used in the infinitive (to maljo) and as a noun (to have/get maljo) referring to persons who have been afflicted. Maljo may be passed on inadvertently, but is believed to be more severe when coming from an envious person or one with bad intentions. It is thought to happen more readily when a person is stared at- especially while eating food. A person who has been taken by the ‘bad eye’ may experience unexplained illness or misfortune. In traditional rural legends, ‘The general belief is that doctors cannot cure maljo----only people who know prayers can "cut" the maljo and thus cure the victim.’

There are several secular approaches to combatting maljo, but more extreme cases are usually referred to spiritual rituals, with a particularly strong influence from the Hindu religion.

In non-religious respects, there is a strong cultural association that between the evil eye and the colour blue. It is believed to ward off maljo when worn as clothing or accessories, so much so that some striking shades are referred to as ‘maljo blue’. Blue ornaments may be used to protect a household, and blue bottles from Milk of Magnesia have been hung on trees or placed in the yard surrounding a property.

Blue soap and Albion Blue (an indigo dye referred to Trinbagonians simply as ‘blue’) are traditionally used for domestic washing, but are also considered to prevent maljo if used in bath water, or to anoint the soles of the feet.

Jumbie beads are the poisonous seeds of the Rosary Pea tree which are used to make jewelry that also wards off maljo and evil spirits.

One superstition is that a pinch can reverse maljo following interpersonal interactions, especially if one is stared at or given a compliment. Some also believe that rubbing one's own saliva in their hair will counteract maljo in general, but particularly from envy of the hair texture and length.

A bath in the sea is also thought to relieve an afflicted person.

Maljo believers are particularly concerned with safeguarding babies and children, who are considered to be most vulnerable to its effects. It may be ‘caused by someone born with a "blight" in the eye, when such a person looks admiringly at a child. It can also occur with a pat on the head, or with just a glance. Whether it is intended or not, compliments (...) can cause maljo. It can be caused by a stranger, a member of the child's immediate family or by another relative.’ It may even be passed on by a parent who is obsessed with their own child. A baby with maljo ‘refuses to eat or drink, cries continually and "pines away.". It may have an "attack of fever".’

Bracelets made of jet beads are traditionally given to newborns to wear as a preventative measure, while elders also recommend securing a bag of blue (dye) to the baby's clothes. This is because a newborn is viewed as most vulnerable.

Following East Indian influence, a tikka is a black dot that is placed on a baby's forehead- thought to distract the attention of the evil eye and protect the child as such.

The most common maljo remedy comes in the form of a Hindu ritual called a jharay. It may be practised at home (usually by parents or elders) or by a pundit or spiritual practitioner. There are many variations to the ritual, and non-Hindu persons readily participate if they are considered to have been affected by maljo.

The main implement in a jharay is either a peacock feather or a cocoyea broom- a traditional broom made using the midrib of the coconut palm leaf. Some also report a knife or machete being used. In some instances, the cocoyea broom is measured against a particular part of the body at the beginning of the ceremony, and it is believed to be confirmation of maljo if the recorded length has changed by the end of the session. The officiant will say a prayer while using the tool of choice to brush the person from head to toe. The prayer is conventionally said in Hindi, but may also be said in English.

A jharay may focus on a specific point of affliction or pain (head, hair, back, feet and so on).

It is not unusual for a jharay ceremony to be carried out on children and babies. ‘People believe that maljo can cause death. Two types were reported: the "'dragging" kind, where the baby gets smaller and smaller and goes through all of the symptoms mentioned above, before withering and dying; the "Twenty-four hour" maljo, said to kill in just twenty-four hours if effective help is not obtained.’

Another Hindu ritual called the oucchay is also employed to heal maljo- though this might also be interchangeably called a jharay. Ingredients such as onion skin, salt, cobweb, hot pepper or mustard seeds, piece of a cocoyea broom, a lock of the victim's hair (in the case of children, it is a lock of the mother's hair) are wrapped in a tissue or newspaper. The officiant will circle the wrapped objects around the victim's body before burning them all. It is believed that if the items create a large, crackling flame and a foul stench, it is an indication that the victim had a severe case of maljo. At the end of the ritual, the victim may be asked to walk away without looking back while the objects burn.

In Afro-Caribbean Spiritual Baptist and Orisha tradition, a special piece of jewelry called a 'guard' will be blessed by an elder, who invokes its protection on the wearer. It may be a waist bead, anklet, bracelet, or necklace. For babies, a large safety pin might be used as a guard.

Greece

The evil eye, known as μάτι (mati), "eye", as an apotropaic visual device, is known to have been a fixture in Greece dating back to at least the 6th century BC, when it commonly appeared on drinking vessels. In Greece, the evil eye is cast away through the process of xematiasma (ξεμάτιασμα), whereby the "healer" silently recites a secret prayer passed over from an older relative of the opposite sex, usually a grandparent. Such prayers are revealed only under specific circumstances, as according to their customs those who reveal them indiscriminately lose their ability to cast off the evil eye. There are several regional versions of the prayer in question, a common one being: "Holy Virgin, Our Lady, if [insert name of the victim] is suffering of the evil eye, release him/her of it." Evil repeated three times. According to custom, if one is indeed afflicted with the evil eye, both victim and "healer" then start yawning profusely. The "healer" then performs the sign of the cross three times, and emits spitting-like sounds in the air three times.

Another "test" used to check if the evil eye was cast is that of the oil: under normal conditions, olive oil floats in water, as it is less dense than water. The test of the oil is performed by placing one drop of olive oil in a glass of water, typically holy water. If the drop floats, the test concludes there is no evil eye involved. If the drop sinks, then it is asserted that the evil eye is cast indeed. Another form of the test is to place two drops of olive oil into a glass of water. If the drops remain separated, the test concludes there is no evil eye, but if they merge, there is. There is also a third form where in a plate full of water the "healer" places three or nine drops of oil. If the oil drops become larger and eventually dissolve in the water there is evil eye. If the drops remain separated from water in a form of a small circle there isn't. The first drops are the most important and the number of drops that dissolve in water indicate the strength of the evil eye. Note that a secret chant is spoken when these tests are conducted. The words of the chant are closed practised and can only be passed from man to woman, or woman to man.

There is another form of the "test" where the "healer" prepares a few cloves by piercing each one with a pin. Then she lights a candle and grabs a pinned clove with a pair of scissors. She then uses it to do the sign of the cross over the afflicted whilst the afflicted is asked to think of a person who may have given him the evil eye. Then the healer holds the clove over the flame. If the clove burns silently, there is no evil eye present; however, if the clove explodes or burns noisily, that means the person in the thoughts of the afflicted is the one who has cast the evil eye. As the clove explodes, the evil eye is released from the afflicted. Cloves that burn with some noise are considered to be λόγια - words - someone foul-mouthing you that you ought to be wary of. The burned cloves are extinguished into a glass of water and are later buried in the garden along with the pins as they are considered to be contaminated. Greek people will also ward off the evil eye by saying φτου να μη σε ματιάξω! which translates to "I spit so that I won't give you the evil eye." Contrary to popular belief, the evil eye is not necessarily given by someone wishing you ill, but it stems from admiration - if one considers admiration to be a compelled emotion of astonishment at a rival's success over one's evil plan. Since it is technically possible to give yourself the evil eye, it is advised to be humble.

The Greek Fathers accepted the traditional belief in the evil eye, but attributed it to the Devil and envy. In Greek theology, the evil eye or vaskania (βασκανία) is considered harmful for the one whose envy inflicts it on others as well as for the sufferer. The Greek Church has an ancient prayer against vaskania from the Megan Hieron Synekdemon (Μέγαν Ιερόν Συνέκδημον) book of prayers.

Assyrians

Assyrians are also strong believers in the evil eye. They will usually wear a blue/turquoise bead around a necklace to be protected from the evil eye. Also, they might pinch the buttocks, comparable to Armenians. It is said that people with green or blue eyes are more prone to the evil eye effect. A simple and instant way of protection in European Christian countries is to make the sign of the cross with your hand and point two fingers, the index finger and the middle finger, towards the supposed source of influence or supposed victim as described in the first chapter of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula published in 1897:

When we started, the crowd round the inn door, which had by this time swelled to a considerable size, all made the sign of the cross and pointed two fingers towards me. With some difficulty, I got a fellow passenger to tell me what they meant. He would not answer at first, but on learning that I was English, he explained that it was a charm or guard against the evil eye.

Turkey

A typical nazar is made of handmade glass featuring concentric circles or teardrop shapes in dark blue, white, light blue and black, occasionally with a yellow/gold edge.

Cultures that have nazars or some variation include Turkey, Romania, Albania, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Greece, Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Armenia, Iran, India, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iraq and Azerbaijan, where the nazar is often hung in homes, offices, cars, children's clothing, or incorporated in jewellery and ornaments. They are a popular choice of souvenir with tourists.

Ethiopia

Belief in the evil eye, or buda (var. bouda), is widespread in Ethiopia. Buda is generally believed to be a power held and wielded by those in a different social group, for example among the metalworkers. Some Ethiopian Christians carry an amulet or talisman, known as a kitab, or will invoke God's name, to ward off the ill effects of buda. A debtera, who is either an unordained priest or educated layperson, will create these protective amulets or talismans.

Senegal

The equivalent of the evil eye in Wolof would be the "thiat". It is believed that beautiful objects may break if enviously stared at by others. To repel the effect of the evil eye, Senegalese people may wear cowrie shell bracelets. The sea shells are said to absorb the negative energy of the thiat and gradually darken until the bracelet breaks. It is also common for superstitious people to wear "gris-gris" made by a marabouts to avoid misfortune.

Pakistan

In Pakistan, the evil eye is called Nazar (نظر). People usually may resort to reading the last three chapters of the Quran, namely Sura Ikhlas, Sura Al-Falaq and Sura Al-Nas. "Masha'Allah" (ما شاء الله) ("God has willed it") is commonly said to ward off the evil eye. Understanding of the evil eye varies by the level of education. Some perceive the use of black color to be useful in protecting from the evil eye. Others use "taawiz" to ward off the evil eye. Truck owners and other public transport vehicles may commonly be seen using a small black cloth on the bumpers to prevent the evil eye.

Southern Italy

The cornicello, "little horn", also called the cornetto ("little horn", plural cornetti), is a long, gently twisted horn-shaped amulet. Cornicelli are usually carved out of red coral or made from gold or silver. The type of horn they are intended to copy is not a curled-over sheep horn or goat horn but rather like the twisted horn of an African eland or a chili pepper. A tooth or tuft of fur of the Italian wolf was worn as a talisman against the evil eye.

One idea that the ribald suggestions made by sexual symbols distract the witch from the mental effort needed to successfully bestow the curse. Another is that since the effect of the eye was to dry up liquids, the drying of the phallus (resulting in male impotence) would be averted by seeking refuge in the moist female genitals. Among the ancient Romans and their cultural descendants in the Mediterranean nations, those who were not fortified with phallic charms had to make use of sexual gestures to avoid the eye. Such gestures include scratching one's testicles (for men), as well as the mano cornuta gesture and the fig sign; a fist with the thumb pressed between the index and middle fingers, representing the phallus within the vagina. In addition to the phallic talismans, statues of hands in these gestures, or covered with magical symbols, were carried by the Romans as talismans.

The wielder of the evil eye, the jettatore, is described as having a striking facial appearance, high arching brows with a stark stare that leaps from his eyes. He often has a reputation for clandestine involvement with dark powers and is the object of gossip about dealings in magic and other forbidden practices. Successful men having tremendous personal magnetism quickly gain notoriety as jettatori. Pope Pius IX was dreaded for his evil eye, and a whole cycle of stories about the disasters that happened in his wake were current in Rome during the latter decades of the 19th century. Public figures of every type, from poets to gangsters, have had their specialized abilities attributed to the power of their eyes.

Malta

The symbol of the eye, known as "l-għajn", is common on traditional fishing boats which are known as luzzu. They are said to protect fishermen from storms and malicious intentions.

Brazil

Brazilians generally will associate mal-olhado, mau-olhado ("act of giving a bad look") or olho gordo ("fat eye" i.e. "gluttonous eye") with envy or jealousy on domestic and garden plants (that, after months or years of health and beauty, will suddenly weaken, wither and die, with no apparent signs of pest, after the visitation of a certain friend or relative), attractive hair and less often economic or romantic success and family harmony.

Unlike in most cultures mal-olhado is not seen to be something that risks young babies. "Pagans" or non-baptized children are instead assumed to be at risk from bruxas (witches), that have malignant intention themselves rather than just mal-olhado. It probably reflects the Galician folktales about the meigas or Portuguese magas, (witches), as Colonial Brazil was primarily settled by Portuguese people, in numbers greater than all Europeans to settle pre-independence United States. Those bruxas are interpreted to have taken the form of moths, often very dark, that disturb children at night and take away their energy. For that reason, Christian Brazilians often have amulets in the form of crucifixes around, beside or inside beds where children sleep.

Nevertheless, older children, especially boys, that fulfill the cultural ideals of behaving extremely well (for example, having no problems whatsoever in eating well a great variety of foods, being obedient and respectful toward adults, kind, polite, studious, and demonstrating no bad blood with other children or their siblings) who unexpectedly turn into problematic adolescents or adults (for example lacking good health habits, extreme laziness or lacking motivation towards their life goals, having eating disorders, or being prone to delinquency), are said to have been victims of mal-olhado coming from parents of children whose behavior was not as admirable.

Amulets that protect against mal-olhado tend to be generally resistant, mildly to strongly toxic and dark plants in specific and strategic places of a garden or the entry to a house. Those include comigo-ninguém-pode ("against-me-nobody-cans"), Dieffenbachia (the dumbcane), espada-de-são-jorge ("St. George's sword"), Sansevieria trifasciata (the snake plant or mother-in-law's tongue) and guiné ("Guinea"), among various other names, Petiveria alliacea (the guinea henweed). For those lacking in space or wanting to "sanitize" specific places, they may all be planted together in a single sete ervas ("seven [lucky] herbs") pot, that will also include arruda (common rue), pimenteira (Capsicum annuum), manjericão (basil) and alecrim (rosemary). (Though the last four ones should not be used for their common culinary purposes by humans.) Other popular amulets against evil eye include: the use of mirrors, on the outside of your home's front door, or also inside your home facing your front door; an elephant figurine with its back to the front door; and coarse salt, placed in specific places at home.

Spain and Latin America

The evil eye or Mal de Ojo has been deeply embedded in Spanish popular culture throughout its history and Spain is the origin of this superstition in Latin America.

In Mexico and Central America, infants are considered at special risk for the evil eye (see mal de ojo, above) and are often given an amulet bracelet as protection, typically with an eye-like spot painted on the amulet. Another preventive measure is allowing admirers to touch the infant or child; in a similar manner, a person wearing an item of clothing that might induce envy may suggest to others that they touch it or some other way dispel envy.

One traditional cure in Latin America involves a curandero (folk healer) sweeping a raw chicken egg over the body of a victim to absorb the power of the person with the evil eye. The egg is later broken into a glass with water and placed under the bed of the patient near the head. Sometimes it is checked immediately because the egg appears as if it has been cooked. When this happens it means that the patient did have Mal de Ojo. Somehow the Mal de Ojo has transferred to the egg and the patient immediately gets well. (Fever, pain and diarrhea, nausea/vomiting goes away instantly) In the traditional Hispanic culture of the Southwestern United States and some parts of Latin America, the egg may be passed over the patient in a cross-shaped pattern all over the body, while reciting The Lord's Prayer. The egg is also placed in a glass with water, under the bed and near the head, sometimes it is examined right away or in the morning and if the egg looks like it has been cooked then it means that they did have Mal de Ojo and the patient will start feeling better. Sometimes if the patient starts getting ill and someone knows that they had stared at the patient, usually a child, if the person who stared goes to the child and touches them, the child's illness goes away immediately so the Mal de Ojo energy is released.

In some parts of South America the act of ojear, which could be translated as to give someone the evil eye, is an involuntary act. Someone may ojear babies, animals and inanimate objects just by staring and admiring them. This may produce illness, discomfort or possibly death on babies or animals and failures on inanimate objects like cars or houses. It's a common belief that since this is an involuntary act made by people with the heavy look, the proper way of protection is by attaching a red ribbon to the animal, baby or object, in order to attract the gaze to the ribbon rather than to the object intended to be protected.

Mexico

Mal de ojo (Mal: Illness - de ojo: Of eye. "To be made ill by an eye's gaze") often occurs without the dimension of envy, but insofar as envy is a part of ojo, it is a variant of this underlying sense of insecurity and relative vulnerability to powerful, hostile forces in the environment. In her study of medical attitudes in the Santa Clara Valley of California, Margaret Clark arrives at essentially the same conclusion: "Among the Spanish-speaking folk of Sal si Puedes, the patient is regarded as a passive and innocent victim of malevolent forces in his environment. These forces may be witches, evil spirits, the consequences of poverty, or virulent bacteria that invade his body. The scapegoat may be a visiting social worker who unwittingly 'cast the evil eye' ... Mexican folk concepts of disease are based in part on the notion that people can be victimized by the careless or malicious behavior of others".

Another aspect of the mal ojo syndrome in Ixtepeji is a disturbance of the hot-cold equilibrium in the victim. According to folk belief, the bad effects of an attack result from the "hot" force of the aggressor entering the child's body and throwing it out of balance. Currier has shown how the Mexican hot-cold system is an unconscious folk model of social relations upon which social anxieties are projected. According to Currier, "the nature of Mexican peasant society is such that each individual must continuously attempt to achieve a balance between two opposing social forces: the tendency toward intimacy and that toward withdrawal. [It is therefore proposed] that the individual's continuous preoccupation with achieving a balance between 'heat' and 'cold' is a way of reenacting, in symbolic terms, a fundamental activity in social relations."

Puerto Rico

In Puerto Rico, Mal de Ojo or "Evil Eye" is believed to be caused when someone gives a wicked glare of jealousy to someone, usually when the person receiving the glare is unaware. The jealousy can be disguised into a positive aspect such as compliments or admiration. Mal de Ojo is considered a curse and illness. It is believed that without proper protection, bad luck, injury, and illness are expected to follow. Mal de Ojo impact is believed to affect speech, relationships, work, family and most notably, health. Since Mal de Ojo centers around envy and compliments, it creates fear of interacting with people that are outside of their culture. Indirect harm could be brought to them or their family. When it comes to children, they are considered to be more susceptible to Mal de Ojo and it is believed that it can weaken them, leading to illness. As a child grows every effort is taken to protect them. When diagnosing Mal de Ojo, it is important to notice the symptoms. Physical symptoms can include: loss of appetite, body weakness, stomach ache, insomnia, fever, nausea, eye infections, lack of energy, and temperament.

Environmental symptoms can include financial, family, and personal problems as simple as a car breaking down. It is important for those who believe to be aware of anything that has gone wrong because it may be linked to Mal de Ojo. Puerto Ricans are protected through the use of Azabache bracelets. Mal de Ojo can also be avoided by touching an infant when giving admiration. The most common practice of protection in Puerto Rico is the use of Azabache bracelets. These bracelets traditionally have a black or red coral amulet attached. The amulet is in the shape of a fist with a protruding index finger knuckle.

Eggs are the most common method to cure Mal De Ojo. The red string and oils also used are more common in other cultures but still used in Puerto Rico depending on the Healer, or the person who is believed to have the ability to cure those who have been targeted. Ultimately, the act of giving someone the "Evil Eye" is a rather simple process and is practiced throughout the world.

India

In the northern states of India, like the Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, the evil eye is called "nazar" (meaning gaze or vision) or more commonly as Buri Nazar. A charm bracelet, tattoo or other object (Nazar battu), or a slogan (Chashme Baddoor (slogan)), may be used to ward-off the evil eye. Some truck owners write the slogan to ward off the evil eye: "buri nazar wale tera muh kala" ("O evil-eyed one, may your face turn black").

In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, people call it as 'Disti' or 'Drusti', while people of Tamil Nadu call it 'drishti' or 'kannu' (translated, means evil eye). The people of Kerala also call it “kannu”, which translates to “eye”. To remove Drishti, people follow several methods based on their culture/area. Items often used are either rock salt, red chilies, white pumpkins, oiled cloth, or lemons coated with kumkuma. People remove Drishti by rotating any one of these items and around the affected person. The person who removes it will then burn the item, or discard it in a place where others are not likely to stamp on these items. People hang pictures of fierce and scary ogres in their homes or vehicles, to ward off the evil eye.

In India, babies and newborn infants will usually have their eye adorned with kajal, or eyeliner. This would be black, as it is believed in India that black wards off the evil eye or any evil auras. The umbilical cord of babies is often preserved and cast into a metal pendant, and tied to a black string — babies can wear this as a chain, bracelet or belt — the belief, once more, is that this protects the infant from drishti. This is a practice that has been followed right from historical times. People usually remove drishti on full-moon or new-moon days, since these days are considered to be auspicious in India.

Indians often leave small patches of rock salt outside their homes, and hang arrangements of green chilies, neem leaves, and lemons on their stoop. The belief is that this will ward away the evil eye cast on families by detractors.

United States

In 1946, the American occultist Henri Gamache published a text called Terrors of the Evil Eye Exposed! (later reprinted as Protection against Evil), which offers directions to defend oneself against the evil eye.

Media and press coverage

In some cultures over-complimenting is said to cast a curse. So does envy. Since ancient times such maledictions have been collectively called the evil eye. According to the book The Evil Eye by folklorist Alan Dundes, the belief's premise is that an individual can cause harm simply by looking at another's person or property. However, protection is easy to come by with talismans that can be worn, carried, or hung in homes, most often incorporating the contours of a human eye. In Aegean countries, people with light-colored eyes are thought to be particularly powerful, and amulets in Greece and Turkey are usually blue orbs. Indians and Jews use charms with palm-forward hands with an eye in the center; Italians employ horns, phallic shapes meant to distract spell casters.