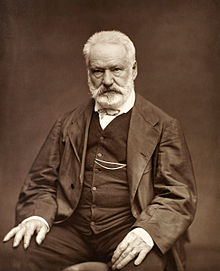

Victor Hugo | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Born | Victor-Marie Hugo 26 February 1802 Besançon, France | ||

| Died | 22 May 1885 (aged 83) Paris, France | ||

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris and Coupvray | ||

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, dramatist, essayist, politician | ||

| Genre | Novel, poetry, theatre | ||

| Literary movement | Romanticism | ||

| Notable works | |||

| Years active | 1829–1883 | ||

| Spouse | |||

| Children | 5 | ||

| Parents | |||

| Personal details | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Political party |

| ||

Victor-Marie Hugo (French: [viktɔʁ maʁi yɡo] (![]() listen); 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, novelist, essayist, playwright, and dramatist of the Romantic movement.

During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote

abundantly in an exceptional variety of genres: lyrics, satires, epics,

philosophical poems, epigrams, novels, history, critical essays,

political speeches, funeral orations, diaries, and letters public and

private, as well as dramas in verse and prose.

listen); 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, novelist, essayist, playwright, and dramatist of the Romantic movement.

During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote

abundantly in an exceptional variety of genres: lyrics, satires, epics,

philosophical poems, epigrams, novels, history, critical essays,

political speeches, funeral orations, diaries, and letters public and

private, as well as dramas in verse and prose.

Hugo is considered to be one of the greatest and best-known French writers. Outside France, his most famous works are the novels Les Misérables, 1862, and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (French: Notre-Dame de Paris), 1831. In France, Hugo is renowned for his poetry collections, such as Les Contemplations (The Contemplations) and La Légende des siècles (The Legend of the Ages). Hugo was at the forefront of the Romantic literary movement with his play Cromwell and drama Hernani. Many of his works have inspired music, both during his lifetime and after his death, including the musicals Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris. He produced more than 4,000 drawings in his lifetime, and campaigned for social causes such as the abolition of capital punishment.

Though he was a committed royalist when young, Hugo's views changed as the decades passed, and he became a passionate supporter of republicanism serving in politics as both deputy and senator. His work touched upon most of the political and social issues and the artistic trends of his time. His opposition to absolutism and his colossal literary achievement established him as a national hero. He was honoured by interment in the Panthéon.

Early life

Victor-Marie Hugo was born on 26 February 1802 in Besançon in Eastern France. He was the youngest son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo (1774–1828) a general in the Napoleonic army, and Sophie Trébuchet (1772–1821); the couple had two more sons: Abel Joseph (1798–1855) and Eugène (1800–1837). The Hugo family came from Nancy in Lorraine where Victor Hugo's grandfather was a wood merchant. Léopold enlisted in the army of Revolutionary France at fourteen, he was an atheist and an ardent supporter of the republic created following the abolition of the monarchy in 1792. Victor's mother Sophie was a devout Catholic who remained loyal to the deposed dynasty. They met in Châteaubriant, a few miles from Nantes in 1796 and married the following year.

Since Hugo's father was an officer in Napoleon's army, the family moved frequently from posting to posting, Sophie had three children in four years. Léopold Hugo wrote to his son that he had been conceived on one of the highest peaks in the Vosges Mountains, on a journey from Lunéville to Besançon. "This elevated origin", he went on, "seems to have had effects on you so that your muse is now continually sublime." Hugo believed himself to have been conceived on 24 June 1801, which is the origin of Jean Valjean's prisoner number 24601.

In 1810 Hugo's father was created Count Hugo de Cogolludo y Sigüenza by then King of Spain Joseph Bonaparte, though it seems that the Spanish title was not legally recognized in France. Hugo later titled himself as a viscount, and it was as "Vicomte Victor Hugo" that he was appointed a peer of France on 13 April 1845.

Weary of the constant moving required by military life, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold and settled in Paris in 1803 with her sons; she began seeing General Victor Fanneau de La Horie, Hugo's godfather who had been a comrade of General Hugo's during the campaign in Vendee. In October 1807 the family rejoined Leopold, now Colonel Hugo, Governor of the province of Avellino. In that city, Victor was taught math by Giuseppe de Samuele Cagnazzi, elder brother of Italian scientist Luca de Samuele Cagnazzi. Sophie found out that Leopold had been living in secret with an Englishwoman called Catherine Thomas.

Sophie Trébuchet, mother of Victor Hugo

General Joseph-Leopold Hugo, father of Victor Hugo

Soon Hugo's father was called to Spain to fight the Peninsular War. Madame Hugo and her children were sent back to Paris in 1808, where they moved to an old convent, 12 Impasse des Feuillantines, an isolated mansion in a deserted quarter of the left bank of the Seine. Hiding in a chapel at the back of the garden was Victor Fanneau de La Horie, who had conspired to restore the Bourbons and been condemned to death a few years earlier. He became a mentor to Victor and his brothers.

In 1811 the family joined their father in Spain. Victor and his brothers were sent to school in Madrid at the Real Colegio de San Antonio de Abad while Sophie returned to Paris on her own, now officially separated from her husband. In 1812 Victor Fanneau de La Horie was arrested and executed. In February 1815 Victor and Eugene were taken away from their mother and placed by their father in the Pension Cordier, a private boarding school in Paris, where Victor and Eugène remained three years while also attending lectures at Lycée Louis le Grand.

On 10 July 1816, Hugo wrote in his diary: “I shall be Chateaubriand or nothing”. In 1817 he wrote a poem for a competition organised by the Academie Française, for which he received an honorable mention. The Academicians refused to believe that he was only fifteen. Victor moved in with his mother 18 rue des Petits-Augustins the following year and began attending law school. Victor fell in love and secretly became engaged, against his mother's wishes, to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher. In June 1821 Sophie Trebuchet died, and Léopold married his long-time mistress Catherine Thomas a month later. Victor married Adèle the following year. In 1819, Victor and his brothers began publishing a periodical called Le Conservateur littéraire.

Career

Hugo published his first novel the year following his marriage (Han d'Islande, 1823), and his second three years later (Bug-Jargal, 1826). Between 1829 and 1840, he published five more volumes of poetry (Les Orientales, 1829; Les Feuilles d'automne, 1831; Les Chants du crépuscule, 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les Ombres, 1840), cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the famous figure in the literary movement of Romanticism and France's pre-eminent literary figure during the early 19th century. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be "Chateaubriand or nothing", and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor in many ways. Like Chateaubriand, Hugo furthered the cause of Romanticism, became involved in politics (though mostly as a champion of Republicanism), and was forced into exile due to his political stances.

The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo's early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry (Odes et poésies diverses) was published in 1822 when he was only 20 years old and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, the collection that followed four years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Victor Hugo's first mature work of fiction was first published in February 1829 by Charles Gosselin without the author's name and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Claude Gueux, a documentary short story about a real-life murderer who had been executed in France, appeared in 1834 and was later considered by Hugo himself to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Misérables.

Hugo became the figurehead of the Romantic literary movement with the plays Cromwell (1827) and Hernani (1830). Hernani announced the arrival of French romanticism: performed at the Comédie-Française, it was greeted with several nights of rioting as romantics and traditionalists clashed over the play's deliberate disregard for neo-classical rules. Hugo's popularity as a playwright grew with subsequent plays, such as Marion Delorme (1831), The King Amuses Himself (1832), and Ruy Blas (1838). Hugo's novel Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris into restoring the much-neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel. The book also inspired a renewed appreciation for pre-Renaissance buildings, which thereafter began to be actively preserved.

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but a full 17 years were needed for Les Misérables to be realised and finally published in 1862. Hugo had used the departure of prisoners for the Bagne of Toulon in one of his early stories, "Le Dernier Jour d'un condamné" He went to Toulon to visit the Bagne in 1839 and took extensive notes, though he did not start writing the book until 1845. On one of the pages of his notes about the prison, he wrote in large block letters a possible name for his hero: " JEAN TRÉJEAN". When the book was finally written, Tréjean became Jean Valjean.

Hugo was acutely aware of the quality of the novel, as evidenced in a letter he wrote to his publisher, Albert Lacroix, on 23 March 1862, "My conviction is that this book is going to be one of the peaks, if not the crowning point of my work." Publication of Les Misérables went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel ("Fantine"), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours and had enormous impact on French society.

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; Taine found it insincere, Barbey d'Aurevilly complained of its vulgarity, Gustave Flaubert found within it "neither truth nor greatness", the Goncourt brothers lambasted its artificiality, and Baudelaire – despite giving favourable reviews in newspapers – castigated it in private as "repulsive and inept". Les Misérables proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the National Assembly of France. Today, the novel remains his most well-known work. It is popular worldwide and has been adapted for cinema, television, and stage shows.

An apocryphal tale has circulated, describing the shortest correspondence in history as having been between Hugo and his publisher Hurst and Blackett in 1862. Hugo was on vacation when Les Misérables was published. He queried the reaction to the work by sending a single-character telegram to his publisher, asking ?. The publisher replied with a single ! to indicate its success. Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer (Toilers of the Sea), published in 1866. The book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of Les Misérables. Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey, where he spent 15 years of exile, Hugo tells of a man who attempts to win the approval of his beloved's father by rescuing his ship, intentionally marooned by its captain who hopes to escape with a treasure of money it is transporting, through an exhausting battle of human engineering against the force of the sea and a battle against an almost mythical beast of the sea, a giant squid. Superficially an adventure, one of Hugo's biographers calls it a "metaphor for the 19th century–technical progress, creative genius and hard work overcoming the immanent evil of the material world."

The word used in Guernsey to refer to squid (pieuvre, also sometimes applied to octopus) was to enter the French language as a result of its use in the book. Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L'Homme Qui Rit (The Man Who Laughs), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. The novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as Flaubert and Émile Zola, whose realist and naturalist novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work.

His last novel, Quatre-vingt-treize (Ninety-Three), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Though Hugo's popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider Ninety-Three to be a work on par with Hugo's better-known novels.

Political life and exile

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie française in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. A group of French academicians, particularly Étienne de Jouy, were fighting against the "romantic evolution" and had managed to delay Victor Hugo's election. Thereafter, he became increasingly involved in French politics.

On the nomination of King Louis-Philippe, Hugo entered the Upper Chamber of Parliament as a pair de France in 1845, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self-government for Poland.

In 1848, Hugo was elected to the National Assembly of the Second Republic as a conservative. In 1849, he broke with the conservatives when he gave a noted speech calling for the end of misery and poverty. Other speeches called for universal suffrage and free education for all children. Hugo's advocacy to abolish the death penalty was renowned internationally.

These parliamentary speeches are published in Œuvres complètes: actes et paroles I : avant l'exil, 1841–1851. Scroll down to the Assemblée Constituante 1848 heading and subsequent pages. When Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti-parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor to France. He moved to Brussels, then Jersey, from which he was expelled for supporting a Jersey newspaper that had criticised Queen Victorias. He finally settled with his family at Hauteville House in Saint Peter Port, Guernsey, where he would live in exile from October 1855 until 1870.

While in exile, Hugo published his famous political pamphlets against Napoleon III, Napoléon le Petit and Histoire d'un crime. The pamphlets were banned in France but nonetheless had a strong impact there. He also composed or published some of his best work during his period in Guernsey, including Les Misérables, and three widely praised collections of poetry (Les Châtiments, 1853; Les Contemplations, 1856; and La Légende des siècles, 1859).

Like most of his contemporaries, Victor Hugo justified colonialism in terms of a civilizing mission and putting an end to the slave trade on the Barbary coast. In a speech delivered on 18 May 1879, during a banquet to celebrate the abolition of slavery, in the presence of the French abolitionist writer and parliamentarian Victor Schœlcher, Hugo declared that the Mediterranean Sea formed a natural divide between " ultimate civilisation and […] utter barbarism," adding "God offers Africa to Europe, Take it," to civilise its indigenous inhabitants.

This might partly explain why in spite of his deep interest and involvement in political matters he remained silent on the Algerian issue. He knew about the atrocities committed by the French Army during the French conquest of Algeria as evidenced by his diary but he never denounced them publicly; however in Les Misérables, Hugo wrote: "Algeria too harshly conquered, and, as in the case of India by the English, with more barbarism than civilization".

After coming in contact with Victor Schœlcher, a writer who fought for the abolition of slavery and French colonialism in the Caribbean, he started strongly campaigning against slavery. In a letter to American abolitionist Maria Weston Chapman, on 6 July 1851, Hugo wrote: Slavery in the United States! It is the duty of this republic to set such a bad example no longer.... The United States must renounce slavery, or they must renounce liberty. In 1859 he wrote a letter asking the United States government, for the sake of their own reputation in the future, to spare abolitionist John Brown's life, Hugo justified Brown's actions by these words: "Assuredly, if insurrection is ever a sacred duty, it must be when it is directed against Slavery". Hugo agreed to diffuse and sell one of his best known drawings, "Le Pendu", an homage to John Brown, so one could "keep alive in souls the memory of this liberator of our black brothers, of this heroic martyr John Brown, who died for Christ just as Christ".

Only one slave on Earth is enough to dishonour the freedom of all men. So the abolition of slavery is, at this hour, the supreme goal of the thinkers

— Victor Hugo, 17 January 1862

Victor Hugo fought a lifelong battle for the abolition of the death penalty as a novelist, diarist, and member of Parliament. The Last Day of a Condemned Man published in 1829 analyses the pangs of a man awaiting execution; several entries of Things Seen (Choses vues), the diary he kept between 1830 and 1885, convey his firm condemnation of what he regarded as a barbaric sentence; on 15 September 1848, seven months after the Revolution of 1848, he delivered a speech before the Assembly and concluded, "You have overthrown the throne. […] Now overthrow the scaffold." His influence was credited in the removal of the death penalty from the constitutions of Geneva, Portugal, and Colombia. He had also pleaded for Benito Juárez to spare the recently captured emperor Maximilian I of Mexico but to no avail.

Although Napoleon III granted an amnesty to all political exiles in 1859, Hugo declined, as it meant he would have to curtail his criticisms of the government. It was only after Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was proclaimed that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

He was in Paris during the siege by the Prussian Army in 1870, famously eating animals given to him by the Paris Zoo. As the siege continued, and food became ever more scarce, he wrote in his diary that he was reduced to "eating the unknown".

During the Paris Commune – the revolutionary government that took power on 18 March 1871 and was toppled on 28 May – Victor Hugo was harshly critical of the atrocities committed on both sides. On 9 April, he wrote in his diary, "In short, this Commune is as idiotic as the National Assembly is ferocious. From both sides, folly." Yet he made a point of offering his support to members of the Commune subjected to brutal repression. He had been in Brussels since 22 March 1871 when in the 27 May issue of the Belgian newspaper l’Indépendance Victor Hugo denounced the government's refusal to grant political asylum to the Communards threatened with imprisonment, banishment or execution. This caused so much uproar that in the evening a mob of fifty to sixty men attempted to force their way into the writer's house shouting "Death to Victor Hugo! Hang him! Death to the scoundrel!".

Victor Hugo, who said "A war between Europeans is a civil war", was an enthusiastic advocate for the creation of the United States of Europe. He expounded his views on the subject in a speech he delivered during the International Peace Congress which took place in Paris in 1849. The Congress, of which Hugo was the President, proved to be an international success, attracting such famous philosophers as Frederic Bastiat, Charles Gilpin, Richard Cobden, and Henry Richard. The conference helped establish Hugo as a prominent public speaker and sparked his international fame, and promoted the idea of the "United States of Europe". On 14 July 1870 he planted the "oak of the United States of Europe" in the garden of Hauteville House where he stayed during his exile on Guernsey from 1856 to 1870. The massacres of Balkan Christians by the Turks in 1876 inspired him to write Pour la Serbie (For Serbia) in his sons' newspaper Le Rappel. This speech is today considered one of the founding acts of the European ideal.

Because of his concern for the rights of artists and copyright, he was a founding member of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale, which led to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. However, in Pauvert's published archives, he states strongly that "any work of art has two authors: the people who confusingly feel something, a creator who translates these feelings, and the people again who consecrate his vision of that feeling. When one of the authors dies, the rights should totally be granted back to the other, the people". He was one of the earlier supporters of the concept of domaine public payant, under which a nominal fee would be charged for copying or performing works in the public domain, and this would go into a common fund dedicated to helping artists, especially young people.

Religious views

Hugo's religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth and under the influence of his mother, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and anti-clerical views. He frequented spiritism during his exile (where he participated also in many séances conducted by Madame Delphine de Girardin) and in later years settled into a rationalist deism similar to that espoused by Voltaire. A census-taker asked Hugo in 1872 if he was a Catholic, and he replied, "No. A Freethinker".

After 1872, Hugo never lost his antipathy towards the Catholic Church. He felt the Church was indifferent to the plight of the working class under the oppression of the monarchy. Perhaps he also was upset by the frequency with which his work appeared on the Church's list of banned books. Hugo counted 740 attacks on Les Misérables in the Catholic press. When Hugo's sons Charles and François-Victor died, he insisted that they be buried without a crucifix or priest. In his will, he made the same stipulation about his own death and funeral.

Yet he believed in life after death and prayed every single morning and night, convinced as he wrote in The Man Who Laughs that "Thanksgiving has wings and flies to its right destination. Your prayer knows its way better than you do".

Hugo's rationalism can be found in poems such as Torquemada (1869, about religious fanaticism), The Pope (1878, anti-clerical), Religions and Religion (1880, denying the usefulness of churches) and, published posthumously, The End of Satan and God (1886 and 1891 respectively, in which he represents Christianity as a griffin and rationalism as an angel). Vincent van Gogh ascribed the saying "Religions pass away, but God remains", actually by Jules Michelet, to Hugo.

Relationship with music

Although Hugo's many talents did not include exceptional musical ability, he nevertheless had a great impact on the music world through the inspiration that his works provided for composers of the 19th and 20th centuries. Hugo himself particularly enjoyed the music of Gluck and Weber. In Les Misérables, he calls the huntsman's chorus in Weber's Euryanthe, "perhaps the most beautiful piece of music ever composed". He also greatly admired Beethoven, and rather unusually for his time, he also appreciated works by composers from earlier centuries such as Palestrina and Monteverdi.

Two famous musicians of the 19th century were friends of Hugo: Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt. The latter played Beethoven in Hugo's home, and Hugo joked in a letter to a friend that, thanks to Liszt's piano lessons, he learned how to play a favourite song on the piano – with only one finger. Hugo also worked with composer Louise Bertin, writing the libretto for her 1836 opera La Esmeralda, which was based on the character in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Although for various reasons the opera closed soon after its fifth performance and is little known today, it has enjoyed a modern revival, both in a piano/song concert version by Liszt at the Festival international Victor Hugo et Égaux 2007 and in a full orchestral version presented in July 2008 at Le Festival de Radio France et Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon.

On the other hand, he had low esteem for Richard Wagner, whom he described as "a man of talent coupled with imbecility."

Well over one thousand musical compositions have been inspired by Hugo's works from the 19th century until the present day. In particular, Hugo's plays, in which he rejected the rules of classical theatre in favour of romantic drama, attracted the interest of many composers who adapted them into operas. More than one hundred operas are based on Hugo's works and among them are Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia (1833), Verdi's Rigoletto (1851) and Ernani (1844), and Ponchielli's La Gioconda (1876).

Hugo's novels, as well as his plays, have been a great source of inspiration for musicians, stirring them to create not only opera and ballet but musical theatre such as Notre-Dame de Paris and the ever-popular Les Misérables, London West End's longest running musical. Additionally, Hugo's beautiful poems have attracted an exceptional amount of interest from musicians, and numerous melodies have been based on his poetry by composers such as Berlioz, Bizet, Fauré, Franck, Lalo, Liszt, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Rachmaninoff, and Wagner.

Today, Hugo's work continues to stimulate musicians to create new compositions. For example, Hugo's novel against capital punishment, The Last Day of a Condemned Man, was adapted into an opera by David Alagna, with a libretto by Frédérico Alagna and premièred by their brother, tenor Roberto Alagna, in 2007. In Guernsey, every two years, the Victor Hugo International Music Festival attracts a wide range of musicians and the premiere of songs specially commissioned from such composers as Guillaume Connesson, Richard Dubugnon, Olivier Kaspar, and Thierry Escaich and based on Hugo's poetry.

Remarkably, not only Hugo's literary production has been the source of inspiration for musical works, but also his political writings have received attention from musicians and have been adapted to music. For instance, in 2009, Italian composer Matteo Sommacal was commissioned by Festival "Bagliori d'autore" and wrote a piece for speaker and chamber ensemble entitled Actes et paroles, with a text elaborated by Chiara Piola Caselli after Victor Hugo's last political speech addressed to the Assemblée législative, "Sur la Revision de la Constitution" (18 July 1851), and premiered in Rome on 19 November 2009, in the auditorium of the Institut français, Centre Saint-Louis, French Embassy to the Holy See, by Piccola Accademia degli Specchi featuring the composer Matthias Kadar.

Declining years and death

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. He was confident that he would be offered the dictatorship, as shown by the notes he kept at the time: "Dictatorship is a crime. This is a crime I am going to commit", but he felt he had to assume that responsibility. Despite his popularity, Hugo lost his bid for re-election to the National Assembly in 1872.

Throughout his life Hugo kept believing in unstoppable humanistic progress. In his last public address on 3 August 1879 he prophesied in an over-optimistic way, "In the twentieth century war will be dead, the scaffold will be dead, hatred will be dead, frontier boundaries will be dead, dogmas will be dead; man will live."

Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle was interned in an insane asylum, and his two sons died. (Adèle's biography inspired the movie The Story of Adele H.) His wife Adèle had died in 1868.

His faithful mistress, Juliette Drouet, died in 1883, only two years before his own death. Despite his personal loss, Hugo remained committed to the cause of political change. On 30 January 1876, he was elected to the newly created Senate. This last phase of his political career was considered a failure. Hugo was a maverick and achieved little in the Senate.

Hugo suffered a mild stroke on 27 June 1878.

To honour the fact that he was entering his 80th year, one of the greatest tributes to a living writer was held. The celebrations began on 25 June 1881, when Hugo was presented with a Sèvres vase, the traditional gift for sovereigns. On 27 June, one of the largest parades in French history was held.

Marchers stretched from the Avenue d'Eylau, where the author was living, down the Champs-Élysées, and all the way to the centre of Paris. The paraders marched for six hours past Hugo as he sat at the window at his house. Every inch and detail of the event was for Hugo; the official guides even wore cornflowers as an allusion to Fantine's song in Les Misérables. On 28 June, the city of Paris changed the name of the Avenue d'Eylau to Avenue Victor-Hugo. Letters addressed to the author were from then on labelled "To Mister Victor Hugo, In his avenue, Paris".

Two days before dying, he left a note with these last words: "To love is to act".

On 20 May 1885, le Petit Journal published the official medical bulletin on Hugo's health condition. "The illustrious patient" was fully conscious and aware that there was no hope for him. They also reported from a reliable source that at one point in the night he had whispered the following alexandrin, "En moi c’est le combat du jour et de la nuit" – "In me, this is the battle between day and night". Le Matin published a slightly different version, "Here is the battle between day and night."

Hugo's death from pneumonia on 22 May 1885, at the age of 83, generated intense national mourning. He was not only revered as a towering figure in literature, he was a statesman who shaped the Third Republic and democracy in France. All his life he remained a defender of liberty, equality and fraternity as well as an adamant champion of French culture. In 1877, aged 75, he wrote, "I am not one of these sweet-tempered old men. I am still exasperated and violent. I shout and I feel indignant and I cry. Woe to anyone who harms France! I do declare I will die a fanatic patriot".

Although he had requested a pauper's funeral, he was awarded a state funeral by decree of President Jules Grévy. More than two million people joined his funeral procession in Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon, where he was buried. He shares a crypt within the Panthéon with Alexandre Dumas and Émile Zola. Most large French towns and cities have a street or square named after him.

Hugo left five sentences as his last will, to be officially published:

Je donne cinquante mille francs aux pauvres. Je veux être enterré dans leur corbillard.

Je refuse l'oraison de toutes les Églises. Je demande une prière à toutes les âmes.

Je crois en Dieu.

I leave 50,000 francs to the poor. I wish to be buried in their hearse.

I refuse [funeral] orations from all Churches. I ask [for] a prayer to all souls.

I believe in God.

Drawings

Hugo produced more than 4,000 drawings. Originally pursued as a casual hobby, drawing became more important to Hugo shortly before his exile when he made the decision to stop writing to devote himself to politics. Drawing became his exclusive creative outlet between 1848 and 1851.

Hugo worked only on paper, and on a small scale; usually in dark brown or black pen-and-ink wash, sometimes with touches of white, and rarely with colour. The surviving drawings are surprisingly accomplished and "modern" in their style and execution, foreshadowing the experimental techniques of Surrealism and Abstract expressionism.

He would not hesitate to use his children's stencils, ink blots, puddles and stains, lace impressions, "pliage" or folding (e.g. Rorschach blots), "grattage" or rubbing, often using the charcoal from matchsticks or his fingers instead of pen or brush. Sometimes he would even toss in coffee or soot to get the effects he wanted. It is reported that Hugo often drew with his left hand or without looking at the page, or during Spiritist séances, to access his unconscious mind, a concept only later popularised by Sigmund Freud.

Hugo kept his artwork out of the public eye, fearing it would overshadow his literary work. However, he enjoyed sharing his drawings with his family and friends, often in the form of ornately handmade calling cards, many of which were given as gifts to visitors when he was in political exile. Some of his work was shown to, and appreciated by, contemporary artists such as van Gogh and Delacroix; the latter expressed the opinion that if Hugo had decided to become a painter instead of a writer, he would have outshone the artists of their century.

Personal life

Family

Marriage

Hugo married Adèle Foucher in October 1822. Despite their respective affairs, they lived together for nearly 46 years until she died in August 1868. Hugo, who was still banished from France, was unable to attend her funeral in Villequier where their daughter Léopoldine was buried. From 1830 to 1837 Adèle had an affair with Charles-Augustin Sainte Beuve, a reviewer and writer.

Children

Adèle and Victor Hugo had their first child, Léopold, in 1823, but the boy died in infancy. On 28 August 1824, the couple's second child, Léopoldine was born, followed by Charles on 4 November 1826, François-Victor on 28 October 1828, and Adèle on 28 July 1830.

Hugo's eldest and favourite daughter, Léopoldine, died in 1843 at the age of 19, shortly after her marriage to Charles Vacquerie. On 4 September, she drowned in the Seine at Villequier when the boat she was in overturned. Her young husband died trying to save her. The death left her father devastated; Hugo was travelling at the time, in the south of France, when he first learned about Léopoldine's death from a newspaper that he read in a café.

He describes his shock and grief in his famous poem "À Villequier":

Hélas ! vers le passé tournant un œil d'envie, |

Alas! My envious eye, turning toward the past, |

He wrote many poems afterward about his daughter's life and death, and at least one biographer claims he never completely recovered from it. His most famous poem is undeniably "Demain, dès l'aube" (Tomorrow, at Dawn), in which he describes visiting her grave.

Exile

Hugo decided to live in exile after Napoleon III's coup d'état at the end of 1851. After leaving France, Hugo lived in Brussels briefly in 1851, and then moved to the Channel Islands, first to Jersey (1852–1855) and then to the smaller island of Guernsey in 1855, where he stayed until Napoleon III's fall from power in 1870. Although Napoleon III proclaimed a general amnesty in 1859, under which Hugo could have safely returned to France, the author stayed in exile, only returning when Napoleon III was removed from power by the creation of the French Third Republic in 1870, as a result of the French defeat at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War. After the Siege of Paris from 1870 to 1871, Hugo lived again in Guernsey from 1872 to 1873, and then finally returned to France for the remainder of his life. In 1871, after the death of his son Charles, Hugo took custody of his grandchildren Jeanne and Georges-Victor.

Other relationships

Juliette Drouet

From February 1833 until her death in 1883, Juliette Drouet devoted her whole life to Victor Hugo, who never married her even after his wife died in 1868. He took her on his numerous trips and she followed him in exile on Guernsey. There Hugo rented a house for her near Hauteville House, his family home. She wrote some 20,000 letters in which she expressed her passion or vented her jealousy on her womanizing lover. On 25 September 1870 during the Siege of Paris (19 September 1870 – 28 January 1871) Hugo feared the worst. He left his children a note reading as follows:

"J.D. She saved my life in December 1851. For me she underwent exile. Never has her soul forsaken mine. Let those who have loved me love her. Let those who have loved me respect her. She is my widow." V.H.

Léonie d’Aunet

For more than seven years, Léonie d’Aunet, who was a married woman, was involved in a love relationship with Hugo. Both were caught in adultery on 5 July 1845. Hugo, who had been a Member of the Chamber of Peers since April, avoided condemnation whereas his mistress had to spend two months in prison and six in a convent. Many years after their separation, Hugo made a point of supporting her financially.

Others

Hugo gave free rein to his sensuality until a few weeks before his death. He sought a wide variety of women of all ages, be they courtesans, actresses, prostitutes, admirers, servants or revolutionaries like Louise Michel for sexual activity. Both a graphomaniac and erotomaniac, he systematically reported his casual affairs using his own code, as Samuel Pepys did, to make sure they would remain secret. For instance, he resorted to Latin abbreviations (osc. for kisses) or to Spanish (Misma. Mismas cosas: The same. Same things). Homophones are frequent: Seins (Breasts) becomes Saint; Poële (Stove) actually refers to Poils (Pubic hair). Analogy also enabled him to conceal the real meaning: A woman's Suisses (Swiss) are her breasts – due to the fact that Switzerland is renowned for its milk. After a rendezvous with a young woman named Laetitia he would write Joie (Happiness) in his diary. If he added t.n. (toute nue) he meant she stripped naked in front of him. The initials S.B. discovered in November 1875 may refer to Sarah Bernhardt.

Gallery

Victor Hugo with his son François-Victor by Auguste de Châtillon, 1836.

Marble bust of Victor Hugo by Auguste Rodin

Memorials

His legacy has been honoured in many ways, including his portrait being placed on French currency.

The people of Guernsey erected a statue by sculptor Jean Boucher in Candie Gardens (Saint Peter Port) to commemorate his stay in the islands. The City of Paris has preserved his residences Hauteville House, Guernsey, and 6, Place des Vosges, Paris, as museums. The house where he stayed in Vianden, Luxembourg, in 1871 has also become a commemorative museum.

The Avenue Victor-Hugo in the 16th arrondissement of Paris bears Hugo's name and links the Place de l'Étoile to the vicinity of the Bois de Boulogne by way of the Place Victor-Hugo. This square is served by a Paris Métro stop also named in his honour. In the town of Béziers there is a main street, a school, hospital and several cafés named after Hugo, and a number of streets and avenues throughout France are named after him. The school Lycée Victor Hugo was founded in his town of birth, Besançon in France. Avenue Victor-Hugo, located in Shawinigan, Quebec, was named to honour him. A street in San Francisco, Hugo Street, is named for him.

In the city of Avellino, Italy, Victor Hugo lived briefly stayed in what is now known as Il Palazzo Culturale when reuniting with his father, Leopold Sigisbert Hugo, in 1808. Hugo would later write about his brief stay here, quoting "C'était un palais de marbre..." ("It was a palace of marble").

There is a statue of Hugo across from the Museo Carlo Bilotti in Rome, Italy.

Victor Hugo is the namesake of the city of Hugoton, Kansas.

In Havana, Cuba, there is a park named after him.

A bust of Hugo stands near the entrance of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing.

A mosaic commemorating Hugo is located on the ceiling of the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress.

The London and North Western Railway named a 'Prince of Wales' Class 4-6-0 No 1134 after Hugo. British Railways perpetuated this memorial, naming Class 92 Electric Unit 92001 after him.

Hugo is venerated as a saint in the Vietnamese religion of Cao Đài, a new religion established in Vietnam in 1926.