Georg Cantor | |

|---|---|

Cantor, early 1900s | |

| Born | Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor March 3, 1845 |

| Died | January 6, 1918 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Set theory |

| Spouse(s) | Vally Guttmann (m. 1874) |

| Awards | Sylvester Medal (1904) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | University of Halle |

| Thesis | De aequationibus secundi gradus indeterminatis (1867) |

| Doctoral advisor | |

Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor (/ˈkæntɔːr/ KAN-tor, German: [ˈɡeːɔʁk ˈfɛʁdinant ˈluːtvɪç ˈfiːlɪp ˈkantɔʁ]; March 3 [O.S. February 19] 1845 – January 6, 1918) was a German mathematician. He created set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. Cantor established the importance of one-to-one correspondence between the members of two sets, defined infinite and well-ordered sets, and proved that the real numbers are more numerous than the natural numbers. In fact, Cantor's method of proof of this theorem implies the existence of an infinity of infinities. He defined the cardinal and ordinal numbers and their arithmetic. Cantor's work is of great philosophical interest, a fact he was well aware of.

Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers was originally regarded as so counter-intuitive – even shocking – that it encountered resistance from mathematical contemporaries such as Leopold Kronecker and Henri Poincaré and later from Hermann Weyl and L. E. J. Brouwer, while Ludwig Wittgenstein raised philosophical objections. Cantor, a devout Lutheran Christian, believed the theory had been communicated to him by God. Some Christian theologians (particularly neo-Scholastics) saw Cantor's work as a challenge to the uniqueness of the absolute infinity in the nature of God – on one occasion equating the theory of transfinite numbers with pantheism – a proposition that Cantor vigorously rejected. It is important to note that not all theologians were against Cantor's theory, prominent neo-scholastic philosopher Constantin Gutberlet was in favor and Cardinal Johann Baptist Franzelin accepted as a valid theory (after Cantor made some important clarifications).

The objections to Cantor's work were occasionally fierce: Leopold Kronecker's public opposition and personal attacks included describing Cantor as a "scientific charlatan", a "renegade" and a "corrupter of youth". Kronecker objected to Cantor's proofs that the algebraic numbers are countable, and that the transcendental numbers are uncountable, results now included in a standard mathematics curriculum. Writing decades after Cantor's death, Wittgenstein lamented that mathematics is "ridden through and through with the pernicious idioms of set theory", which he dismissed as "utter nonsense" that is "laughable" and "wrong". Cantor's recurring bouts of depression from 1884 to the end of his life have been blamed on the hostile attitude of many of his contemporaries, though some have explained these episodes as probable manifestations of a bipolar disorder.

The harsh criticism has been matched by later accolades. In 1904, the Royal Society awarded Cantor its Sylvester Medal, the highest honor it can confer for work in mathematics. David Hilbert defended it from its critics by declaring, "No one shall expel us from the paradise that Cantor has created."

Life of Georg Cantor

Youth and studies

Georg Cantor was born in 1845 in the western merchant colony of Saint Petersburg, Russia, and brought up in the city until he was eleven. Cantor, the oldest of six children, was regarded as an outstanding violinist. His grandfather Franz Böhm (1788–1846) (the violinist Joseph Böhm's brother) was a well-known musician and soloist in a Russian imperial orchestra. Cantor's father had been a member of the Saint Petersburg stock exchange; when he became ill, the family moved to Germany in 1856, first to Wiesbaden, then to Frankfurt, seeking milder winters than those of Saint Petersburg. In 1860, Cantor graduated with distinction from the Realschule in Darmstadt; his exceptional skills in mathematics, trigonometry in particular, were noted. In August 1862, he then graduated from the "Höhere Gewerbeschule Darmstadt", now the Technische Universität Darmstadt. In 1862, Cantor entered the Swiss Federal Polytechnic. After receiving a substantial inheritance upon his father's death in June 1863, Cantor shifted his studies to the University of Berlin, attending lectures by Leopold Kronecker, Karl Weierstrass and Ernst Kummer. He spent the summer of 1866 at the University of Göttingen, then and later a center for mathematical research. Cantor was a good student, and he received his doctorate degree in 1867.

Teacher and researcher

Cantor submitted his dissertation on number theory at the University of Berlin in 1867. After teaching briefly in a Berlin girls' school, Cantor took up a position at the University of Halle, where he spent his entire career. He was awarded the requisite habilitation for his thesis, also on number theory, which he presented in 1869 upon his appointment at Halle University.

In 1874, Cantor married Vally Guttmann. They had six children, the last (Rudolph) born in 1886. Cantor was able to support a family despite modest academic pay, thanks to his inheritance from his father. During his honeymoon in the Harz mountains, Cantor spent much time in mathematical discussions with Richard Dedekind, whom he had met two years earlier while on Swiss holiday.

Cantor was promoted to extraordinary professor in 1872 and made full professor in 1879. To attain the latter rank at the age of 34 was a notable accomplishment, but Cantor desired a chair at a more prestigious university, in particular at Berlin, at that time the leading German university. However, his work encountered too much opposition for that to be possible. Kronecker, who headed mathematics at Berlin until his death in 1891, became increasingly uncomfortable with the prospect of having Cantor as a colleague, perceiving him as a "corrupter of youth" for teaching his ideas to a younger generation of mathematicians. Worse yet, Kronecker, a well-established figure within the mathematical community and Cantor's former professor, disagreed fundamentally with the thrust of Cantor's work ever since he intentionally delayed the publication of Cantor's first major publication in 1874. Kronecker, now seen as one of the founders of the constructive viewpoint in mathematics, disliked much of Cantor's set theory because it asserted the existence of sets satisfying certain properties, without giving specific examples of sets whose members did indeed satisfy those properties. Whenever Cantor applied for a post in Berlin, he was declined, and it usually involved Kronecker, so Cantor came to believe that Kronecker's stance would make it impossible for him ever to leave Halle.

In 1881, Cantor's Halle colleague Eduard Heine died, creating a vacant chair. Halle accepted Cantor's suggestion that it be offered to Dedekind, Heinrich M. Weber and Franz Mertens, in that order, but each declined the chair after being offered it. Friedrich Wangerin was eventually appointed, but he was never close to Cantor.

In 1882, the mathematical correspondence between Cantor and Dedekind came to an end, apparently as a result of Dedekind's declining the chair at Halle. Cantor also began another important correspondence, with Gösta Mittag-Leffler in Sweden, and soon began to publish in Mittag-Leffler's journal Acta Mathematica. But in 1885, Mittag-Leffler was concerned about the philosophical nature and new terminology in a paper Cantor had submitted to Acta. He asked Cantor to withdraw the paper from Acta while it was in proof, writing that it was "... about one hundred years too soon." Cantor complied, but then curtailed his relationship and correspondence with Mittag-Leffler, writing to a third party, "Had Mittag-Leffler had his way, I should have to wait until the year 1984, which to me seemed too great a demand! ... But of course I never want to know anything again about Acta Mathematica."

Cantor suffered his first known bout of depression in May 1884. Criticism of his work weighed on his mind: every one of the fifty-two letters he wrote to Mittag-Leffler in 1884 mentioned Kronecker. A passage from one of these letters is revealing of the damage to Cantor's self-confidence:

... I don't know when I shall return to the continuation of my scientific work. At the moment I can do absolutely nothing with it, and limit myself to the most necessary duty of my lectures; how much happier I would be to be scientifically active, if only I had the necessary mental freshness.

This crisis led him to apply to lecture on philosophy rather than mathematics. He also began an intense study of Elizabethan literature thinking there might be evidence that Francis Bacon wrote the plays attributed to William Shakespeare (see Shakespearean authorship question); this ultimately resulted in two pamphlets, published in 1896 and 1897.

Cantor recovered soon thereafter, and subsequently made further important contributions, including his diagonal argument and theorem. However, he never again attained the high level of his remarkable papers of 1874–84, even after Kronecker's death on December 29, 1891. He eventually sought, and achieved, a reconciliation with Kronecker. Nevertheless, the philosophical disagreements and difficulties dividing them persisted.

In 1889, Cantor was instrumental in founding the German Mathematical Society and chaired its first meeting in Halle in 1891, where he first introduced his diagonal argument; his reputation was strong enough, despite Kronecker's opposition to his work, to ensure he was elected as the first president of this society. Setting aside the animosity Kronecker had displayed towards him, Cantor invited him to address the meeting, but Kronecker was unable to do so because his wife was dying from injuries sustained in a skiing accident at the time. Georg Cantor was also instrumental in the establishment of the first International Congress of Mathematicians, which was held in Zürich, Switzerland, in 1897.

Later years and death

After Cantor's 1884 hospitalization, there is no record that he was in any sanatorium again until 1899. Soon after that second hospitalization, Cantor's youngest son Rudolph died suddenly on December 16 (Cantor was delivering a lecture on his views on Baconian theory and William Shakespeare), and this tragedy drained Cantor of much of his passion for mathematics. Cantor was again hospitalized in 1903. One year later, he was outraged and agitated by a paper presented by Julius König at the Third International Congress of Mathematicians. The paper attempted to prove that the basic tenets of transfinite set theory were false. Since the paper had been read in front of his daughters and colleagues, Cantor perceived himself as having been publicly humiliated. Although Ernst Zermelo demonstrated less than a day later that König's proof had failed, Cantor remained shaken, and momentarily questioning God. Cantor suffered from chronic depression for the rest of his life, for which he was excused from teaching on several occasions and repeatedly confined in various sanatoria. The events of 1904 preceded a series of hospitalizations at intervals of two or three years. He did not abandon mathematics completely, however, lecturing on the paradoxes of set theory (Burali-Forti paradox, Cantor's paradox, and Russell's paradox) to a meeting of the Deutsche Mathematiker-Vereinigung in 1903, and attending the International Congress of Mathematicians at Heidelberg in 1904.

In 1911, Cantor was one of the distinguished foreign scholars invited to attend the 500th anniversary of the founding of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. Cantor attended, hoping to meet Bertrand Russell, whose newly published Principia Mathematica repeatedly cited Cantor's work, but this did not come about. The following year, St. Andrews awarded Cantor an honorary doctorate, but illness precluded his receiving the degree in person.

Cantor retired in 1913, living in poverty and suffering from malnourishment during World War I. The public celebration of his 70th birthday was canceled because of the war. In June 1917, he entered a sanatorium for the last time and continually wrote to his wife asking to be allowed to go home. Georg Cantor had a fatal heart attack on January 6, 1918, in the sanatorium where he had spent the last year of his life.

Mathematical work

Cantor's work between 1874 and 1884 is the origin of set theory. Prior to this work, the concept of a set was a rather elementary one that had been used implicitly since the beginning of mathematics, dating back to the ideas of Aristotle. No one had realized that set theory had any nontrivial content. Before Cantor, there were only finite sets (which are easy to understand) and "the infinite" (which was considered a topic for philosophical, rather than mathematical, discussion). By proving that there are (infinitely) many possible sizes for infinite sets, Cantor established that set theory was not trivial, and it needed to be studied. Set theory has come to play the role of a foundational theory in modern mathematics, in the sense that it interprets propositions about mathematical objects (for example, numbers and functions) from all the traditional areas of mathematics (such as algebra, analysis and topology) in a single theory, and provides a standard set of axioms to prove or disprove them. The basic concepts of set theory are now used throughout mathematics.

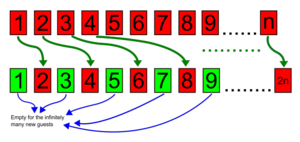

In one of his earliest papers, Cantor proved that the set of real numbers is "more numerous" than the set of natural numbers; this showed, for the first time, that there exist infinite sets of different sizes. He was also the first to appreciate the importance of one-to-one correspondences (hereinafter denoted "1-to-1 correspondence") in set theory. He used this concept to define finite and infinite sets, subdividing the latter into denumerable (or countably infinite) sets and nondenumerable sets (uncountably infinite sets).

Cantor developed important concepts in topology and their relation to cardinality. For example, he showed that the Cantor set, discovered by Henry John Stephen Smith in 1875, is nowhere dense, but has the same cardinality as the set of all real numbers, whereas the rationals are everywhere dense, but countable. He also showed that all countable dense linear orders without end points are order-isomorphic to the rational numbers.

Cantor introduced fundamental constructions in set theory, such as the power set of a set A, which is the set of all possible subsets of A. He later proved that the size of the power set of A is strictly larger than the size of A, even when A is an infinite set; this result soon became known as Cantor's theorem. Cantor developed an entire theory and arithmetic of infinite sets, called cardinals and ordinals, which extended the arithmetic of the natural numbers. His notation for the cardinal numbers was the Hebrew letter (aleph) with a natural number subscript; for the ordinals he employed the Greek letter ω (omega). This notation is still in use today.

The Continuum hypothesis, introduced by Cantor, was presented by David Hilbert as the first of his twenty-three open problems in his address at the 1900 International Congress of Mathematicians in Paris. Cantor's work also attracted favorable notice beyond Hilbert's celebrated encomium. The US philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce praised Cantor's set theory and, following public lectures delivered by Cantor at the first International Congress of Mathematicians, held in Zurich in 1897, Adolf Hurwitz and Jacques Hadamard also both expressed their admiration. At that Congress, Cantor renewed his friendship and correspondence with Dedekind. From 1905, Cantor corresponded with his British admirer and translator Philip Jourdain on the history of set theory and on Cantor's religious ideas. This was later published, as were several of his expository works.

Number theory, trigonometric series and ordinals

Cantor's first ten papers were on number theory, his thesis topic. At the suggestion of Eduard Heine, the Professor at Halle, Cantor turned to analysis. Heine proposed that Cantor solve an open problem that had eluded Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, Rudolf Lipschitz, Bernhard Riemann, and Heine himself: the uniqueness of the representation of a function by trigonometric series. Cantor solved this problem in 1869. It was while working on this problem that he discovered transfinite ordinals, which occurred as indices n in the nth derived set Sn of a set S of zeros of a trigonometric series. Given a trigonometric series f(x) with S as its set of zeros, Cantor had discovered a procedure that produced another trigonometric series that had S1 as its set of zeros, where S1 is the set of limit points of S. If Sk+1 is the set of limit points of Sk, then he could construct a trigonometric series whose zeros are Sk+1. Because the sets Sk were closed, they contained their limit points, and the intersection of the infinite decreasing sequence of sets S, S1, S2, S3,... formed a limit set, which we would now call Sω, and then he noticed that Sω would also have to have a set of limit points Sω+1, and so on. He had examples that went on forever, and so here was a naturally occurring infinite sequence of infinite numbers ω, ω + 1, ω + 2, ...

Between 1870 and 1872, Cantor published more papers on trigonometric series, and also a paper defining irrational numbers as convergent sequences of rational numbers. Dedekind, whom Cantor befriended in 1872, cited this paper later that year, in the paper where he first set out his celebrated definition of real numbers by Dedekind cuts. While extending the notion of number by means of his revolutionary concept of infinite cardinality, Cantor was paradoxically opposed to theories of infinitesimals of his contemporaries Otto Stolz and Paul du Bois-Reymond, describing them as both "an abomination" and "a cholera bacillus of mathematics". Cantor also published an erroneous "proof" of the inconsistency of infinitesimals.

Set theory

The beginning of set theory as a branch of mathematics is often marked by the publication of Cantor's 1874 paper, "Ueber eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen" ("On a Property of the Collection of All Real Algebraic Numbers"). This paper was the first to provide a rigorous proof that there was more than one kind of infinity. Previously, all infinite collections had been implicitly assumed to be equinumerous (that is, of "the same size" or having the same number of elements). Cantor proved that the collection of real numbers and the collection of positive integers are not equinumerous. In other words, the real numbers are not countable. His proof differs from diagonal argument that he gave in 1891. Cantor's article also contains a new method of constructing transcendental numbers. Transcendental numbers were first constructed by Joseph Liouville in 1844.

Cantor established these results using two constructions. His first construction shows how to write the real algebraic numbers as a sequence a1, a2, a3, .... In other words, the real algebraic numbers are countable. Cantor starts his second construction with any sequence of real numbers. Using this sequence, he constructs nested intervals whose intersection contains a real number not in the sequence. Since every sequence of real numbers can be used to construct a real not in the sequence, the real numbers cannot be written as a sequence – that is, the real numbers are not countable. By applying his construction to the sequence of real algebraic numbers, Cantor produces a transcendental number. Cantor points out that his constructions prove more – namely, they provide a new proof of Liouville's theorem: Every interval contains infinitely many transcendental numbers. Cantor's next article contains a construction that proves the set of transcendental numbers has the same "power" (see below) as the set of real numbers.

Between 1879 and 1884, Cantor published a series of six articles in Mathematische Annalen that together formed an introduction to his set theory. At the same time, there was growing opposition to Cantor's ideas, led by Leopold Kronecker, who admitted mathematical concepts only if they could be constructed in a finite number of steps from the natural numbers, which he took as intuitively given. For Kronecker, Cantor's hierarchy of infinities was inadmissible, since accepting the concept of actual infinity would open the door to paradoxes which would challenge the validity of mathematics as a whole. Cantor also introduced the Cantor set during this period.

The fifth paper in this series, "Grundlagen einer allgemeinen Mannigfaltigkeitslehre" ("Foundations of a General Theory of Aggregates"), published in 1883, was the most important of the six and was also published as a separate monograph. It contained Cantor's reply to his critics and showed how the transfinite numbers were a systematic extension of the natural numbers. It begins by defining well-ordered sets. Ordinal numbers are then introduced as the order types of well-ordered sets. Cantor then defines the addition and multiplication of the cardinal and ordinal numbers. In 1885, Cantor extended his theory of order types so that the ordinal numbers simply became a special case of order types.

In 1891, he published a paper containing his elegant "diagonal argument" for the existence of an uncountable set. He applied the same idea to prove Cantor's theorem: the cardinality of the power set of a set A is strictly larger than the cardinality of A. This established the richness of the hierarchy of infinite sets, and of the cardinal and ordinal arithmetic that Cantor had defined. His argument is fundamental in the solution of the Halting problem and the proof of Gödel's first incompleteness theorem. Cantor wrote on the Goldbach conjecture in 1894.

In 1895 and 1897, Cantor published a two-part paper in Mathematische Annalen under Felix Klein's editorship; these were his last significant papers on set theory. The first paper begins by defining set, subset, etc., in ways that would be largely acceptable now. The cardinal and ordinal arithmetic are reviewed. Cantor wanted the second paper to include a proof of the continuum hypothesis, but had to settle for expositing his theory of well-ordered sets and ordinal numbers. Cantor attempts to prove that if A and B are sets with A equivalent to a subset of B and B equivalent to a subset of A, then A and B are equivalent. Ernst Schröder had stated this theorem a bit earlier, but his proof, as well as Cantor's, was flawed. Felix Bernstein supplied a correct proof in his 1898 PhD thesis; hence the name Cantor–Bernstein–Schröder theorem.

One-to-one correspondence

Cantor's 1874 Crelle paper was the first to invoke the notion of a 1-to-1 correspondence, though he did not use that phrase. He then began looking for a 1-to-1 correspondence between the points of the unit square and the points of a unit line segment. In an 1877 letter to Richard Dedekind, Cantor proved a far stronger result: for any positive integer n, there exists a 1-to-1 correspondence between the points on the unit line segment and all of the points in an n-dimensional space. About this discovery Cantor wrote to Dedekind: "Je le vois, mais je ne le crois pas!" ("I see it, but I don't believe it!") The result that he found so astonishing has implications for geometry and the notion of dimension.

In 1878, Cantor submitted another paper to Crelle's Journal, in which he defined precisely the concept of a 1-to-1 correspondence and introduced the notion of "power" (a term he took from Jakob Steiner) or "equivalence" of sets: two sets are equivalent (have the same power) if there exists a 1-to-1 correspondence between them. Cantor defined countable sets (or denumerable sets) as sets which can be put into a 1-to-1 correspondence with the natural numbers, and proved that the rational numbers are denumerable. He also proved that n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn has the same power as the real numbers R, as does a countably infinite product of copies of R. While he made free use of countability as a concept, he did not write the word "countable" until 1883. Cantor also discussed his thinking about dimension, stressing that his mapping between the unit interval and the unit square was not a continuous one.

This paper displeased Kronecker and Cantor wanted to withdraw it; however, Dedekind persuaded him not to do so and Karl Weierstrass supported its publication. Nevertheless, Cantor never again submitted anything to Crelle.

Continuum hypothesis

Cantor was the first to formulate what later came to be known as the continuum hypothesis or CH: there exists no set whose power is greater than that of the naturals and less than that of the reals (or equivalently, the cardinality of the reals is exactly aleph-one, rather than just at least aleph-one). Cantor believed the continuum hypothesis to be true and tried for many years to prove it, in vain. His inability to prove the continuum hypothesis caused him considerable anxiety.

The difficulty Cantor had in proving the continuum hypothesis has been underscored by later developments in the field of mathematics: a 1940 result by Kurt Gödel and a 1963 one by Paul Cohen together imply that the continuum hypothesis can be neither proved nor disproved using standard Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory plus the axiom of choice (the combination referred to as "ZFC").

Absolute infinite, well-ordering theorem, and paradoxes

In 1883, Cantor divided the infinite into the transfinite and the absolute.

The transfinite is increasable in magnitude, while the absolute is unincreasable. For example, an ordinal α is transfinite because it can be increased to α + 1. On the other hand, the ordinals form an absolutely infinite sequence that cannot be increased in magnitude because there are no larger ordinals to add to it. In 1883, Cantor also introduced the well-ordering principle "every set can be well-ordered" and stated that it is a "law of thought".

Cantor extended his work on the absolute infinite by using it in a proof. Around 1895, he began to regard his well-ordering principle as a theorem and attempted to prove it. In 1899, he sent Dedekind a proof of the equivalent aleph theorem: the cardinality of every infinite set is an aleph. First, he defined two types of multiplicities: consistent multiplicities (sets) and inconsistent multiplicities (absolutely infinite multiplicities). Next he assumed that the ordinals form a set, proved that this leads to a contradiction, and concluded that the ordinals form an inconsistent multiplicity. He used this inconsistent multiplicity to prove the aleph theorem. In 1932, Zermelo criticized the construction in Cantor's proof.

Cantor avoided paradoxes by recognizing that there are two types of multiplicities. In his set theory, when it is assumed that the ordinals form a set, the resulting contradiction implies only that the ordinals form an inconsistent multiplicity. In contrast, Bertrand Russell treated all collections as sets, which leads to paradoxes. In Russell's set theory, the ordinals form a set, so the resulting contradiction implies that the theory is inconsistent. From 1901 to 1903, Russell discovered three paradoxes implying that his set theory is inconsistent: the Burali-Forti paradox (which was just mentioned), Cantor's paradox, and Russell's paradox. Russell named paradoxes after Cesare Burali-Forti and Cantor even though neither of them believed that they had found paradoxes.

In 1908, Zermelo published his axiom system for set theory. He had two motivations for developing the axiom system: eliminating the paradoxes and securing his proof of the well-ordering theorem. Zermelo had proved this theorem in 1904 using the axiom of choice, but his proof was criticized for a variety of reasons. His response to the criticism included his axiom system and a new proof of the well-ordering theorem. His axioms support this new proof, and they eliminate the paradoxes by restricting the formation of sets.

In 1923, John von Neumann developed an axiom system that eliminates the paradoxes by using an approach similar to Cantor's—namely, by identifying collections that are not sets and treating them differently. Von Neumann stated that a class is too big to be a set if it can be put into one-to-one correspondence with the class of all sets. He defined a set as a class that is a member of some class and stated the axiom: A class is not a set if and only if there is a one-to-one correspondence between it and the class of all sets. This axiom implies that these big classes are not sets, which eliminates the paradoxes since they cannot be members of any class. Von Neumann also used his axiom to prove the well-ordering theorem: Like Cantor, he assumed that the ordinals form a set. The resulting contradiction implies that the class of all ordinals is not a set. Then his axiom provides a one-to-one correspondence between this class and the class of all sets. This correspondence well-orders the class of all sets, which implies the well-ordering theorem. In 1930, Zermelo defined models of set theory that satisfy von Neumann's axiom.

Philosophy, religion, literature and Cantor's mathematics

The concept of the existence of an actual infinity was an important shared concern within the realms of mathematics, philosophy and religion. Preserving the orthodoxy of the relationship between God and mathematics, although not in the same form as held by his critics, was long a concern of Cantor's. He directly addressed this intersection between these disciplines in the introduction to his Grundlagen einer allgemeinen Mannigfaltigkeitslehre, where he stressed the connection between his view of the infinite and the philosophical one. To Cantor, his mathematical views were intrinsically linked to their philosophical and theological implications – he identified the Absolute Infinite with God, and he considered his work on transfinite numbers to have been directly communicated to him by God, who had chosen Cantor to reveal them to the world. He was a devout Lutheran whose explicit Christian beliefs shaped his philosophy of science. Joseph Dauben has traced the effect Cantor's Christian convictions had on the development of transfinite set theory.

Debate among mathematicians grew out of opposing views in the philosophy of mathematics regarding the nature of actual infinity. Some held to the view that infinity was an abstraction which was not mathematically legitimate, and denied its existence. Mathematicians from three major schools of thought (constructivism and its two offshoots, intuitionism and finitism) opposed Cantor's theories in this matter. For constructivists such as Kronecker, this rejection of actual infinity stems from fundamental disagreement with the idea that nonconstructive proofs such as Cantor's diagonal argument are sufficient proof that something exists, holding instead that constructive proofs are required. Intuitionism also rejects the idea that actual infinity is an expression of any sort of reality, but arrive at the decision via a different route than constructivism. Firstly, Cantor's argument rests on logic to prove the existence of transfinite numbers as an actual mathematical entity, whereas intuitionists hold that mathematical entities cannot be reduced to logical propositions, originating instead in the intuitions of the mind. Secondly, the notion of infinity as an expression of reality is itself disallowed in intuitionism, since the human mind cannot intuitively construct an infinite set. Mathematicians such as L. E. J. Brouwer and especially Henri Poincaré adopted an intuitionist stance against Cantor's work. Finally, Wittgenstein's attacks were finitist: he believed that Cantor's diagonal argument conflated the intension of a set of cardinal or real numbers with its extension, thus conflating the concept of rules for generating a set with an actual set.

Some Christian theologians saw Cantor's work as a challenge to the uniqueness of the absolute infinity in the nature of God. In particular, neo-Thomist thinkers saw the existence of an actual infinity that consisted of something other than God as jeopardizing "God's exclusive claim to supreme infinity". Cantor strongly believed that this view was a misinterpretation of infinity, and was convinced that set theory could help correct this mistake: "... the transfinite species are just as much at the disposal of the intentions of the Creator and His absolute boundless will as are the finite numbers.". It is to note that prominent neo-scholastic german philosopher Constantin Gutberlet was in favor of such theory, holding that it didn't oppose the nature of God.

Cantor also believed that his theory of transfinite numbers ran counter to both materialism and determinism – and was shocked when he realized that he was the only faculty member at Halle who did not hold to deterministic philosophical beliefs.

It was important to Cantor that his philosophy provided an "organic explanation" of nature, and in his 1883 Grundlagen, he said that such an explanation could only come about by drawing on the resources of the philosophy of Spinoza and Leibniz. In making these claims, Cantor may have been influenced by FA Trendelenburg, whose lecture courses he attended at Berlin, and in turn Cantor produced a Latin commentary on Book 1 of Spinoza's Ethica. FA Trendelenburg was also the examiner of Cantor's Habilitationsschrift.

In 1888, Cantor published his correspondence with several philosophers on the philosophical implications of his set theory. In an extensive attempt to persuade other Christian thinkers and authorities to adopt his views, Cantor had corresponded with Christian philosophers such as Tilman Pesch and Joseph Hontheim, as well as theologians such as Cardinal Johann Baptist Franzelin, who once replied by equating the theory of transfinite numbers with pantheism. Although later this Cardinal accepted the theory as valid, due to some clarifications from Cantor's. Cantor even sent one letter directly to Pope Leo XIII himself, and addressed several pamphlets to him.

Cantor's philosophy on the nature of numbers led him to affirm a belief in the freedom of mathematics to posit and prove concepts apart from the realm of physical phenomena, as expressions within an internal reality. The only restrictions on this metaphysical system are that all mathematical concepts must be devoid of internal contradiction, and that they follow from existing definitions, axioms, and theorems. This belief is summarized in his assertion that "the essence of mathematics is its freedom." These ideas parallel those of Edmund Husserl, whom Cantor had met in Halle.

Meanwhile, Cantor himself was fiercely opposed to infinitesimals, describing them as both an "abomination" and "the cholera bacillus of mathematics".

Cantor's 1883 paper reveals that he was well aware of the opposition his ideas were encountering: "... I realize that in this undertaking I place myself in a certain opposition to views widely held concerning the mathematical infinite and to opinions frequently defended on the nature of numbers."

Hence he devotes much space to justifying his earlier work, asserting that mathematical concepts may be freely introduced as long as they are free of contradiction and defined in terms of previously accepted concepts. He also cites Aristotle, René Descartes, George Berkeley, Gottfried Leibniz, and Bernard Bolzano on infinity. Instead, he always strongly rejected Kant's philosophy, in the realms of both the philosophy of mathematics and metaphysics. He shared B. Russell's motto "Kant or Cantor", and defined Kant "yonder sophistical Philistine who knew so little mathematics."

Cantor's ancestry

Cantor's paternal grandparents were from Copenhagen and fled to Russia from the disruption of the Napoleonic Wars. There is very little direct information on them. Cantor's father, Georg Waldemar Cantor, was educated in the Lutheran mission in Saint Petersburg, and his correspondence with his son shows both of them as devout Lutherans. Very little is known for sure about Georg Waldemar's origin or education. Cantor's mother, Maria Anna Böhm, was an Austro-Hungarian born in Saint Petersburg and baptized Roman Catholic; she converted to Protestantism upon marriage. However, there is a letter from Cantor's brother Louis to their mother, stating:

Mögen wir zehnmal von Juden abstammen und ich im Princip noch so sehr für Gleichberechtigung der Hebräer sein, im socialen Leben sind mir Christen lieber ...

("Even if we were descended from Jews ten times over, and even though I may be, in principle, completely in favour of equal rights for Hebrews, in social life I prefer Christians...") which could be read to imply that she was of Jewish ancestry.

According to biographers Eric Temple Bell, Cantor was of Jewish descent, although both parents were baptized. In a 1971 article entitled "Towards a Biography of Georg Cantor", the British historian of mathematics Ivor Grattan-Guinness mentions (Annals of Science 27, pp. 345–391, 1971) that he was unable to find evidence of Jewish ancestry. (He also states that Cantor's wife, Vally Guttmann, was Jewish).

In a letter written to Paul Tannery in 1896 (Paul Tannery, Memoires Scientifique 13 Correspondence, Gauthier-Villars, Paris, 1934, p. 306), Cantor states that his paternal grandparents were members of the Sephardic Jewish community of Copenhagen. Specifically, Cantor states in describing his father: "Er ist aber in Kopenhagen geboren, von israelitischen Eltern, die der dortigen portugisischen Judengemeinde...." ("He was born in Copenhagen of Jewish (lit: 'Israelite') parents from the local Portuguese-Jewish community.") In addition, Cantor's maternal great uncle, a Hungarian violinist Josef Böhm, has been described as Jewish, which may imply that Cantor's mother was at least partly descended from the Hungarian Jewish community.

In a letter to Bertrand Russell, Cantor described his ancestry and self-perception as follows:

Neither my father nor my mother were of German blood, the first being a Dane, borne in Kopenhagen, my mother of Austrian Hungar descension. You must know, Sir, that I am not a regular just Germain, for I am born 3 March 1845 at Saint Peterborough, Capital of Russia, but I went with my father and mother and brothers and sister, eleven years old in the year 1856, into Germany.

There were documented statements, during the 1930s, that called this Jewish ancestry into question:

More often [i.e., than the ancestry of the mother] the question has been discussed of whether Georg Cantor was of Jewish origin. About this it is reported in a notice of the Danish genealogical Institute in Copenhagen from the year 1937 concerning his father: "It is hereby testified that Georg Woldemar Cantor, born 1809 or 1814, is not present in the registers of the Jewish community, and that he completely without doubt was not a Jew ..."

Biographies

Until the 1970s, the chief academic publications on Cantor were two short monographs by Arthur Moritz Schönflies (1927) – largely the correspondence with Mittag-Leffler – and Fraenkel (1930). Both were at second and third hand; neither had much on his personal life. The gap was largely filled by Eric Temple Bell's Men of Mathematics (1937), which one of Cantor's modern biographers describes as "perhaps the most widely read modern book on the history of mathematics"; and as "one of the worst". Bell presents Cantor's relationship with his father as Oedipal, Cantor's differences with Kronecker as a quarrel between two Jews, and Cantor's madness as Romantic despair over his failure to win acceptance for his mathematics. Grattan-Guinness (1971) found that none of these claims were true, but they may be found in many books of the intervening period, owing to the absence of any other narrative. There are other legends, independent of Bell – including one that labels Cantor's father a foundling, shipped to Saint Petersburg by unknown parents. A critique of Bell's book is contained in Joseph Dauben's biography. Writes Dauben:

Cantor devoted some of his most vituperative correspondence, as well as a portion of the Beiträge, to attacking what he described at one point as the 'infinitesimal Cholera bacillus of mathematics', which had spread from Germany through the work of Thomae, du Bois Reymond and Stolz, to infect Italian mathematics ... Any acceptance of infinitesimals necessarily meant that his own theory of number was incomplete. Thus to accept the work of Thomae, du Bois-Reymond, Stolz and Veronese was to deny the perfection of Cantor's own creation. Understandably, Cantor launched a thorough campaign to discredit Veronese's work in every way possible.