The concept of television was the work of many individuals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots initially starting from back even in the 18th century. The first practical transmissions of moving images over a radio system used mechanical rotating perforated disks to scan a scene into a time-varying signal that could be reconstructed at a receiver back into an approximation of the original image. Development of television was interrupted by the Second World War. After the end of the war, all-electronic methods of scanning and displaying images became standard. Several different standards for addition of color to transmitted images were developed with different regions using technically incompatible signal standards. Television broadcasting expanded rapidly after World War II, becoming an important mass medium for advertising, propaganda, and entertainment.

Television broadcasts can be distributed over the air by VHF and UHF radio signals from terrestrial transmitting stations, by microwave signals from Earth orbiting satellites, or by wired transmission to individual consumers by cable TV. Many countries have moved away from the original analog radio transmission methods and now use digital television standards, providing additional operating features and conserving radio spectrum bandwidth for more profitable uses. Television programming can also be distributed over the Internet.

Television broadcasting may be funded by advertising revenue, by private or governmental organizations prepared to underwrite the cost, or in some countries, by television license fees paid by owners of receivers. Some services, especially carried by cable or satellite, are paid by subscriptions.

Television broadcasting is supported by continuing technical developments such as long-haul microwave networks, which allow distribution of programming over a wide geographic area. Video recording methods allow programming to be edited and replayed for later use. Three-dimensional television has been used commercially but has not received wide consumer acceptance owing to the limitations of display methods.

Mechanical television

Facsimile transmission systems pioneered methods of mechanically scanning graphics in the early 19th century. The Scottish inventor Alexander Bain introduced the facsimile machine between 1843 and 1846. The English physicist Frederick Bakewell demonstrated a working laboratory version in 1851. The first practical facsimile system, working on telegraph lines, was developed and put into service by the Italian priest Giovanni Caselli from 1856 onward.

Willoughby Smith, an English electrical engineer, discovered the photoconductivity of the element selenium in 1873. This led, among other technologies, towards telephotography, a way to send still images through phone lines, as early as in 1895, as well as any kind of electronic image scanning devices, both still and in motion, and ultimately to TV cameras.

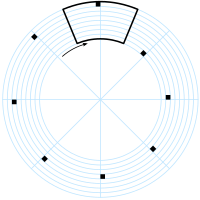

As a 23-year-old German university student, Paul Julius Gottlieb Nipkow, proposed and patented the Nipkow disk in 1884. This was a spinning disk with a spiral pattern of holes in it, so each hole scanned a line of the image. Although he never built a working model of the system, variations of Nipkow's spinning-disk "image rasterizer" became exceedingly common. Constantin Perskyi had coined the word television in a paper read to the International Electricity Congress at the International World Fair in Paris on August 24, 1900. Perskyi's paper reviewed the existing electromechanical technologies, mentioning the work of Nipkow and others. However, it was not until 1907 that developments in amplification tube technology, by Lee de Forest and Arthur Korn among others, made the design practical.

The first demonstration of the instantaneous transmission of images was by Georges Rignoux and A. Fournier in Paris in 1909. A matrix of 64 selenium cells, individually wired to a mechanical commutator, served as an electronic retina. In the receiver, a type of Kerr cell modulated the light and a series of variously angled mirrors attached to the edge of a rotating disc scanned the modulated beam onto the display screen. A separate circuit regulated synchronization. The 8×8 pixel resolution in this proof-of-concept demonstration was just sufficient to clearly transmit individual letters of the alphabet. An updated image was transmitted "several times" each second.

In 1911, Boris Rosing and his student Vladimir Zworykin created a system that used a mechanical mirror-drum scanner to transmit, in Zworykin's words, "very crude images" over wires to the "Braun tube" (cathode ray tube or "CRT") in the receiver. Moving images were not possible because, in the scanner, "the sensitivity was not enough and the selenium cell was very laggy".

In May 1914 Archibald Low gave the first demonstration of his television system at the Institute of Automobile Engineers in London. He called his system 'Televista'. The events were widely reported worldwide and were generally entitled Seeing By Wireless. The demonstrations had so impressed Harry Gordon Selfridge that he included Televista in his 1914 Scientific and Electrical Exhibition at his store. It also interested Deputy Consul General Carl Raymond Loop who filled a US consular report from London containing considerable detail about Low's system. Low's invention employed a matrix detector (camera) and a mosaic screen (receiver/viewer) with an electro-mechanical scanning mechanism that moved a rotating roller over the cell contacts providing a multiplex signal to the camera/viewer data link. The receiver employed a similar roller. The two rollers were synchronised. Hence, it was unlike any of the intervening TV systems of the 20th Century and in many respects, Low had a digital TV system 80 years before the advent of today's digital TV. World War One began shortly after these demonstrations in London and Low became involved in sensitive military work, and so he did not apply for a patent until 1917. His "Televista" Patent No. 191,405 titled "Improved Apparatus for the Electrical Transmission of Optical Images" was finally published in 1923—delayed possibly for security reasons. The patent states that the scanning roller had a row of conductive contacts corresponding to the cells in each row of the array and arranged to sample each cell in turn as the roller rotated. The receivers roller was similarly constructed and each revolution addressed a row of cells as the rollers traversed over their array of cells. Loops report tells us that... "The roller is driven by a motor of 3,000 revolutions per minute, and the resulting variations of light are transmitted along an ordinary conducting wire."

The cell-matrix shown in the patent is 22×22 (approaching an impressive 500 cells/pixels) and each 'camera' cell had a corresponding 'viewer' cell. Loop said it was a "screen divided into a large number of small squares cells of selenium" and the patent states "into each... space I place a selenium cell". Low covered the cells with a liquid dielectric and the roller connected with each cell in turn through this medium as it rotated and travelled over the array. The receiver used bimetallic elements that acted as shutters "transmitting more or less light according to the current passing through them..." as stated in the patent. Low said the main deficiency of the system was the selenium cells used for converting light waves into electric impulses, which responded too slowly thus spoiling the effect. Loop reported that "The system has been tested through a resistance equivalent to a distance of four miles, but in the opinion of Doctor Low there is no reason why it should not be equally effective over far greater distances. The patent states that this connection could be either wired or wireless. The cost of the apparatus is considerable because the conductive sections of the roller are made of platinum..."

In 1914 the demonstrations certainly garnered a lot of media interest with The Times reporting on 30 May:

An inventor, Dr. A. M. Low, has discovered a means of transmitting visual images by wire. If all goes well with this invention, we shall soon be able, it seems, to see people at a distance.

On 29 May the Daily Chronicle reported:

Dr. Low gave a demonstration for the first time in public, with a new apparatus that he has invented, for seeing, he claims by electricity, by which it is possible for persons using a telephone to see each other at the same time

In 1927 Ronald Frank Tiltman asked Low to write the introduction to his book in which he acknowledged Low's work, referring to Low's various related patents with an apology that they were of 'too technical a nature for inclusion'. Later in his 1938 patent Low envisioned a much larger 'camera' cell density achieved by a deposition process of caesium alloy on an insulated substrate that was subsequently sectioned to divide it into cells, the essence of today's technology. Low's system failed for various reasons, mostly due to its inability to reproduce an image by reflected light and simultaneously depict gradations of light and shade. It can be added to the list of systems, like that of Boris Rosing, that predominantly reproduced shadows. With subsequent technological advances, many such ideas could be made viable decades later, but at the time they were impractical.

In 1923, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird envisaged a complete television system that employed the Nipkow disk. Nipkow's was an obscure, forgotten patent and not at all obvious at the time. He created his first prototypes in Hastings, where he was recovering from a serious illness. In late 1924, Baird returned to London to continue his experiments there. On March 25, 1925, Baird gave the first public demonstration of televised silhouette images in motion, at Selfridge's Department Store in London. Since human faces had inadequate contrast to show up on his system at this time, he televised cut-outs and by mid-1925 the head of a ventriloquist's dummy he later named "Stooky Bill", whose face was painted to highlight its contrast. "Stooky Bill" also did not complain about the long hours of staying still in front of the blinding level of light used in these experiments. On October 2, 1925, suddenly the dummy's head came through on the screen with incredible clarity. On January 26, 1926, he demonstrated the transmission of images of real human faces for 40 distinguished scientists of the Royal Institution. This is widely regarded as being the world's first public television demonstration. Baird's system used Nipkow disks for both scanning the image and displaying it. A brightly illuminated subject was placed in front of a spinning Nipkow disk set with lenses that swept images across a static photocell. At this time, it is believed that it was a thallium sulphide (Thalofide) cell, developed by Theodore Case in the US, that detected the light reflected from the subject. This was transmitted by radio to a receiver unit, where the video signal was applied to a neon bulb behind a similar Nipkow disk synchronised with the first. The brightness of the neon lamp was varied in proportion to the brightness of each spot on the image. As each lens in the disk passed by, one scan line of the image was reproduced. With this early apparatus, Baird's disks had 16 lenses, yet in conjunction with the other discs used produced moving images with 32 scan-lines, just enough to recognize a human face. He began with a frame-rate of five per second, which was soon increased to a rate of 121⁄2 frames per second and 30 scan-lines.

In 1927, Baird transmitted a signal over 438 miles (705 km) of telephone line between London and Glasgow. In 1928, Baird's company (Baird Television Development Company/Cinema Television) broadcast the first transatlantic television signal, between London and New York, and the first shore-to-ship transmission. In 1929, he became involved in the first experimental mechanical television service in Germany. In November of the same year, Baird and Bernard Natan of Pathé established France's first television company, Télévision-Baird-Natan. In 1931, he made the first outdoor remote broadcast, of the Derby. In 1932, he demonstrated ultra-short wave television. Baird Television Limited's mechanical systems reached a peak of 240 lines of resolution at the company's Crystal Palace studios, and later on BBC television broadcasts in 1936, though for action shots (as opposed to a seated presenter) the mechanical system did not scan the televised scene directly. Instead, a 17.5mm film was shot, rapidly developed, and then scanned while the film was still wet.

The Scophony Company's success with their mechanical system in the 1930s enabled them to take their operations to the USA when World War II curtailed their business in Britain.

An American inventor, Charles Francis Jenkins, also pioneered the television. He published an article on "Motion Pictures by Wireless" in 1913, but it was not until December 1923 that he transmitted moving silhouette images for witnesses. On June 13, 1925, Jenkins publicly demonstrated the synchronized transmission of silhouette pictures. In 1925, Jenkins used a Nipkow disk and transmitted the silhouette image of a toy windmill in motion, over a distance of five miles (from a naval radio station in Maryland to his laboratory in Washington, D.C.), using a lensed disk scanner with a 48-line resolution. He was granted U.S. patent 1,544,156 (Transmitting Pictures over Wireless) on June 30, 1925 (filed March 13, 1922).

On December 25, 1926, Kenjiro Takayanagi demonstrated a television system with a 40-line resolution that employed a Nipkow disk scanner and CRT display at Hamamatsu Industrial High School in Japan. This prototype is still on display at the Takayanagi Memorial Museum at Shizuoka University, Hamamatsu Campus. By 1927, Takayanagi improved the resolution to 100 lines, which was not surpassed until 1931. By 1928, he was the first to transmit human faces in halftones. His work had an influence on the later work of Vladimir K. Zworykin. In Japan he is viewed as the man who completed the first all-electronic television. His research toward creating a production model was halted by the US after Japan lost World War II.

In 1927, a team from Bell Telephone Laboratories demonstrated television transmission from Washington to New York, using a prototype flat panel plasma display to make the images visible to an audience. The monochrome display measured two feet by three feet and had 2500 pixels.

Herbert E. Ives and Frank Gray of Bell Telephone Laboratories gave a dramatic demonstration of mechanical television on April 7, 1927. The reflected-light television system included both small and large viewing screens. The small receiver had a two-inch-wide by 2.5-inch-high screen. The large receiver had a screen 24 inches wide by 30 inches high. Both sets were capable of reproducing reasonably accurate, monochromatic moving images. Along with the pictures, the sets also received synchronized sound. The system transmitted images over two paths: first, a copper wire link from Washington to New York City, then a radio link from Whippany, New Jersey. Comparing the two transmission methods, viewers noted no difference in quality. Subjects of the telecast included Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. A flying-spot scanner beam illuminated these subjects. The scanner that produced the beam had a 50-aperture disk. The disc revolved at a rate of 18 frames per second, capturing one frame about every 56 milliseconds. (Today's systems typically transmit 30 or 60 frames per second, or one frame every 33.3 or 16.7 milliseconds respectively.) Television historian Albert Abramson underscored the significance of the Bell Labs demonstration: "It was in fact the best demonstration of a mechanical television system ever made to this time. It would be several years before any other system could even begin to compare with it in picture quality."

In 1928, WRGB (then W2XB) was started as the world's first television station. It broadcast from the General Electric facility in Schenectady, New York. It was popularly known as "WGY Television".

Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, Léon Theremin had been developing a mirror drum-based television, starting with 16-line resolution in 1925, then 32 lines and eventually 64 using interlacing in 1926. As part of his thesis on May 7, 1926, Theremin electrically transmitted and then projected near-simultaneous moving images on a five-foot square screen. By 1927 he achieved an image of 100 lines, a resolution that was not surpassed until 1931 by RCA, with 120 lines.

Because only a limited number of holes could be made in the disks, and disks beyond a certain diameter became impractical, image resolution in mechanical television broadcasts was relatively low, ranging from about 30 lines up to about 120. Nevertheless, the image quality of 30-line transmissions steadily improved with technical advances, and by 1933 the UK broadcasts using the Baird system were remarkably clear. A few systems ranging into the 200-line region also went on the air. Two of these were the 180-line system that Compagnie des Compteurs (CDC) installed in Paris in 1935, and the 180-line system that Peck Television Corp. started in 1935 at station VE9AK in Montreal.

Anton Codelli (22 March 1875 – 28 April 1954), a Slovenian nobleman, was a passionate inventor. Among other things, he had devised a miniature refrigerator for cars and a new rotary engine design. Intrigued by television, he decided to apply his technical skills to the new medium. At the time, the biggest challenge in television technology was to transmit images with sufficient resolution to reproduce recognizable figures. As recounted by media historian Melita Zajc, most inventors were determined to increase the number of lines used by their systems – some were approaching what was then the magic number of 100 lines. But Baron Codelli had a different idea. In 1929, he developed a television device with a single line – but one that formed a continuous spiral on the screen. Codelli based his ingenious design on his understanding of the human eye. He knew that objects seen in peripheral vision don't need to be as sharp as those in the center. The baron's mechanical television system, whose image was sharpest in the middle, worked well, and he was soon able to transmit images of his wife, Ilona von Drasche-Lazar, over the air. Despite the backing of the German electronics giant Telefunken, however, Codelli's television system never became a commercial reality. Electronic television ultimately emerged as the dominant system, and Codelli moved on to other projects. His invention was largely forgotten.

The advancement of all-electronic television (including image dissectors and other camera tubes and cathode ray tubes for the reproducer) marked the beginning of the end for mechanical systems as the dominant form of television. Mechanical TV usually only produced small images. It was the main type of TV until the 1930s. The last mechanical television broadcasts ended in 1939 at stations run by a handful of public universities in the United States.

Electronic television

In 1897 J. J. Thomson, an English physicist, in his three famous experiments was able to deflect cathode rays, a fundamental function of the modern cathode-ray tube (CRT). The earliest version of the CRT was invented by the German physicist Karl Ferdinand Braun in 1897 and is also known as the Braun tube. It was a cold-cathode diode, a modification of the Crookes tube with a phosphor-coated screen. A cathode ray tube was successfully demonstrated as a displaying device by the German Professor Max Dieckmann in 1906, his experimental results were published by the journal Scientific American in 1909. In 1908 Alan Archibald Campbell-Swinton, fellow of the UK Royal Society, published a letter in the scientific journal Nature in which he described how "distant electric vision" could be achieved by using a cathode ray tube (or "Braun" tube) as both a transmitting and receiving device. He expanded on his vision in a speech given in London in 1911 and reported in The Times and the Journal of the Röntgen Society. In a letter to Nature published in October 1926, Campbell-Swinton also announced the results of some "not very successful experiments" he had conducted with G. M. Minchin and J. C. M. Stanton. They had attempted to generate an electrical signal by projecting an image onto a selenium-coated metal plate that was simultaneously scanned by a cathode ray beam. These experiments were conducted before March 1914, when Minchin died. They were later repeated in 1937 by two different teams, H. Miller and J. W. Strange from EMI, and H. Iams and A. Rose from RCA. Both teams succeeded in transmitting "very faint" images with the original Campbell-Swinton's selenium-coated plate. Although others had experimented with using a cathode ray tube as a receiver, the concept of using one as a transmitter was novel. The first cathode ray tube to use a hot cathode was developed by John B. Johnson (who gave his name to the term Johnson noise) and Harry Weiner Weinhart of Western Electric, and became a commercial product in 1922.

The problem of low sensitivity to light resulting in low electrical output from transmitting or "camera" tubes would be solved with the introduction of charge-storage technology by the Hungarian engineer Kálmán Tihanyi in the beginning of 1924. In 1926, Tihanyi designed a television system utilizing fully electronic scanning and display elements and employing the principle of "charge storage" within the scanning (or "camera") tube. His solution was a camera tube that accumulated and stored electrical charges ("photoelectrons") within the tube throughout each scanning cycle. The device was first described in a patent application he filed in Hungary in March 1926 for a television system he dubbed "Radioskop". After further refinements included in a 1928 patent application, Tihanyi's patent was declared void in Great Britain in 1930, and so he applied for patents in the United States. Although his breakthrough would be incorporated into the design of RCA's "iconoscope" in 1931, the U.S. patent for Tihanyi's transmitting tube would not be granted until May 1939. The patent for his receiving tube had been granted the previous October. Both patents had been purchased by RCA prior to their approval. Tihanyi's charge storage idea remains a basic principle in the design of imaging devices for television to the present day.

On December 25, 1926, Kenjiro Takayanagi demonstrated a TV system with a 40-line resolution that employed a CRT display at Hamamatsu Industrial High School in Japan. Takayanagi did not apply for a patent.

On September 7, 1927, Philo Farnsworth's image dissector camera tube transmitted its first image, a simple straight line, at his laboratory at 202 Green Street in San Francisco. By September 3, 1928, Farnsworth had developed the system sufficiently to hold a demonstration for the press. This is widely regarded as the first electronic television demonstration. In 1929, the system was further improved by elimination of a motor generator, so that his television system now had no mechanical parts. That year, Farnsworth transmitted the first live human images with his system, including a three and a half-inch image of his wife Elma ("Pem") with her eyes closed (possibly due to the bright lighting required).

Meanwhile, Vladimir Zworykin was also experimenting with the cathode ray tube to create and show images. While working for Westinghouse Electric in 1923, he began to develop an electronic camera tube. But in a 1925 demonstration, the image was dim, had low contrast and poor definition, and was stationary. Zworykin's imaging tube never got beyond the laboratory stage. But RCA, which acquired the Westinghouse patent, asserted that the patent for Farnsworth's 1927 image dissector was written so broadly that it would exclude any other electronic imaging device. Thus RCA, on the basis of Zworykin's 1923 patent application, filed a patent interference suit against Farnsworth. The U.S. Patent Office examiner disagreed in a 1935 decision, finding priority of invention for Farnsworth against Zworykin. Farnsworth claimed that Zworykin's 1923 system would be unable to produce an electrical image of the type to challenge his patent. Zworykin received a patent in 1928 for a color transmission version of his 1923 patent application, he also divided his original application in 1931. Zworykin was unable or unwilling to introduce evidence of a working model of his tube that was based on his 1923 patent application. In September 1939, after losing an appeal in the courts and determined to go forward with the commercial manufacturing of television equipment, RCA agreed to pay Farnsworth US$1 million over a ten-year period, in addition to license payments, to use Farnsworth's patents.

In 1933 RCA introduced an improved camera tube that relied on Tihanyi's charge storage principle. Dubbed the Iconoscope by Zworykin, the new tube had a light sensitivity of about 75,000 lux, and thus was claimed to be much more sensitive than Farnsworth's image dissector. However, Farnsworth had overcome his power problems with his Image Dissector through the invention of a unique "multipactor" device that he began work on in 1930, and demonstrated in 1931. This small tube could amplify a signal reportedly to the 60th power or better and showed great promise in all fields of electronics. A problem with the multipactor, unfortunately, was that it wore out at an unsatisfactory rate.

At the Berlin Radio Show in August 1931, Manfred von Ardenne gave a public demonstration of a television system using a CRT for both transmission and reception. However, Ardenne had not developed a camera tube, using the CRT instead as a flying-spot scanner to scan slides and film. Philo Farnsworth gave the world's first public demonstration of an all-electronic television system, using a live camera, at the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia on August 25, 1934, and for ten days afterwards.

In Britain the EMI engineering team led by Isaac Shoenberg applied in 1932 for a patent for a new device they dubbed "the Emitron", which formed the heart of the cameras they designed for the BBC. In November 1936, a 405-line broadcasting service employing the Emitron began at studios in Alexandra Palace and transmitted from a specially built mast atop one of the Victorian building's towers. It alternated for a short time with Baird's mechanical system in adjoining studios but was more reliable and visibly superior. This was the world's first regular high-definition television service.

The original American iconoscope was noisy, had a high ratio of interference to signal, and ultimately gave disappointing results, especially when compared to the high definition mechanical scanning systems then becoming available. The EMI team under the supervision of Isaac Shoenberg analyzed how the iconoscope (or Emitron) produces an electronic signal and concluded that its real efficiency was only about 5% of the theoretical maximum. They solved this problem by developing and patenting in 1934 two new camera tubes dubbed super-Emitron and CPS Emitron. The super-Emitron was between ten and fifteen times more sensitive than the original Emitron and iconoscope tubes and, in some cases, this ratio was considerably greater. It was used for an outside broadcasting by the BBC, for the first time, on Armistice Day 1937, when the general public could watch on a television set how the King laid a wreath at the Cenotaph. This was the first time that anyone could broadcast a live street scene from cameras installed on the roof of neighbor buildings, because neither Farnsworth nor RCA could do the same before the 1939 New York World's Fair.

On the other hand, in 1934, Zworykin shared some patent rights with the German licensee company Telefunken. The "image iconoscope" ("Superikonoskop" in Germany) was produced as a result of the collaboration. This tube is essentially identical to the super-Emitron. The production and commercialization of the super-Emitron and image iconoscope in Europe were not affected by the patent war between Zworykin and Farnsworth, because Dieckmann and Hell had priority in Germany for the invention of the image dissector, having submitted a patent application for their Lichtelektrische Bildzerlegerröhre für Fernseher (Photoelectric Image Dissector Tube for Television) in Germany in 1925, two years before Farnsworth did the same in the United States. The image iconoscope (Superikonoskop) became the industrial standard for public broadcasting in Europe from 1936 until 1960, when it was replaced by the vidicon and plumbicon tubes. Indeed, it was the representative of the European tradition in electronic tubes competing against the American tradition represented by the image orthicon. The German company Heimann produced the Superikonoskop for the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, later Heimann also produced and commercialized it from 1940 to 1955, finally the Dutch company Philips produced and commercialized the image iconoscope and multicon from 1952 to 1958.

American television broadcasting at the time consisted of a variety of markets in a wide range of sizes, each competing for programming and dominance with separate technology, until deals were made and standards agreed upon in 1941. RCA, for example, used only Iconoscopes in the New York area, but Farnsworth Image Dissectors in Philadelphia and San Francisco. In September 1939, RCA agreed to pay the Farnsworth Television and Radio Corporation royalties over the next ten years for access to Farnsworth's patents. With this historic agreement in place, RCA integrated much of what was best about the Farnsworth Technology into their systems. In 1941, the United States implemented 525-line television.

The world's first 625-line television standard was designed in the Soviet Union in 1944, and became a national standard in 1946. The first broadcast in 625-line standard occurred in 1948 in Moscow. The concept of 625 lines per frame was subsequently implemented in the European CCIR standard.

In 1936, Kálmán Tihanyi described the principle of plasma display, the first flat panel display system.

In 1978, James P. Mitchell described, prototyped and demonstrated what was perhaps the earliest monochromatic flat panel LED television display LED display targeted at replacing the CRT.

Color television

The basic idea of using three monochrome images to produce a color image had been experimented with almost as soon as black-and-white televisions had first been built. Older televisions have the RGB (Red-Green-Blue) color scheme while modern televisions focus on LEDs to create the image. Among the earliest published proposals for television was one by Maurice Le Blanc in 1880 for a color system, including the first mentions in television literature of line and frame scanning, although he gave no practical details. Polish inventor Jan Szczepanik patented a color television system in 1897, using a selenium photoelectric cell at the transmitter and an electromagnet controlling an oscillating mirror and a moving prism at the receiver. But his system contained no means of analyzing the spectrum of colors at the transmitting end, and could not have worked as he described it. Another inventor, Hovannes Adamian, also experimented with color television as early as 1907. The first color television project is claimed by him, and was patented in Germany on March 31, 1908, patent No. 197183, then in Britain, on April 1, 1908, patent No. 7219, in France (patent No. 390326) and in Russia in 1910 (patent No. 17912).

Scottish inventor John Logie Baird demonstrated the world's first color transmission on July 3, 1928, using scanning discs at the transmitting and receiving ends with three spirals of apertures, each spiral with filters of a different primary color; and three light sources at the receiving end, with a commutator to alternate their illumination. Baird also made the world's first color broadcast on February 4, 1938, sending a mechanically scanned 120-line image from Baird's Crystal Palace studios to a projection screen at London's Dominion Theatre.

Mechanically scanned color television was also demonstrated by Bell Laboratories in June 1929 using three complete systems of photoelectric cells, amplifiers, glow-tubes and color filters, with a series of mirrors to superimpose the red, green and blue images into one full color image.

The first practical hybrid system was again pioneered by John Logie Baird. In 1940 he publicly demonstrated a color television combining a traditional black-and-white display with a rotating colored disc. This device was very "deep", but was later improved with a mirror folding the light path into an entirely practical device resembling a large conventional console. However, Baird was not happy with the design, and as early as 1944 had commented to a British government committee that a fully electronic device would be better.

Mexican inventor Guillermo González Camarena also played an important role in early TV. His experiments with TV (known as telectroescopía at first) began in 1931 and led to a patent for the "trichromatic field sequential system" color television in 1940.

In 1939, Hungarian engineer Peter Carl Goldmark introduced an electro-mechanical system while at CBS, which contained an Iconoscope sensor. The CBS field-sequential color system was partly mechanical, with a disc made of red, blue, and green filters spinning inside the television camera at 1,200 rpm, and a similar disc spinning in synchronization in front of the cathode ray tube inside the receiver set. The system was first demonstrated to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on August 29, 1940, and shown to the press on September 4.

CBS began experimental color field tests using film as early as August 28, 1940, and live cameras by November 12. NBC (owned by RCA) made its first field test of color television on February 20, 1941. CBS began daily color field tests on June 1, 1941. These color systems were not compatible with existing black-and-white television sets, and as no color television sets were available to the public at this time, viewing of the color field tests was restricted to RCA and CBS engineers and the invited press. The War Production Board halted the manufacture of television and radio equipment for civilian use from April 22, 1942, to August 20, 1945, limiting any opportunity to introduce color television to the general public.

As early as 1940, Baird had started work on a fully electronic system he called the "Telechrome". Early Telechrome devices used two electron guns aimed at either side of a phosphor plate. Using cyan and magenta phosphors, a reasonable limited-color image could be obtained. He also demonstrated the same system using monochrome signals to produce a 3D image (called "stereoscopic" at the time). A demonstration on August 16, 1944 was the first example of a practical color television system. Work on the Telechrome continued and plans were made to introduce a three-gun version for full color. This used a patterned version of the phosphor plate, with the guns aimed at ridges on one side of the plate. However, Baird's untimely death in 1946 ended development of the Telechrome system.

Similar concepts were common through the 1940s and 1950s, differing primarily in the way they re-combined the colors generated by the three guns. The Geer tube was similar to Baird's concept, but used small pyramids with the phosphors deposited on their outside faces, instead of Baird's 3D patterning on a flat surface. The Penetron used three layers of phosphor on top of each other and increased the power of the beam to reach the upper layers when drawing those colors. The Chromatron used a set of focusing wires to select the colored phosphors arranged in vertical stripes on the tube.

One of the great technical challenges of introducing color broadcast television was the desire to conserve bandwidth, potentially three times that of the existing black-and-white standards, and not use an excessive amount of radio spectrum. In the United States, after considerable research, the National Television Systems Committee approved an all-electronic Compatible color system developed by RCA, which encoded the color information separately from the brightness information and greatly reduced the resolution of the color information in order to conserve bandwidth. The brightness image remained compatible with existing black-and-white television sets at slightly reduced resolution, while color televisions could decode the extra information in the signal and produce a limited-resolution color display. The higher resolution black-and-white and lower resolution color images combine in the brain to produce a seemingly high-resolution color image. The NTSC standard represented a major technical achievement.

Although all-electronic color was introduced in the U.S. in 1953, high prices and the scarcity of color programming greatly slowed its acceptance in the marketplace. The first national color broadcast (the 1954 Tournament of Roses Parade) occurred on January 1, 1954, but during the following ten years most network broadcasts, and nearly all local programming, continued to be in black-and-white. It was not until the mid-1960s that color sets started selling in large numbers, due in part to the color transition of 1965 in which it was announced that over half of all network prime-time programming would be broadcast in color that fall. The first all-color prime-time season came just one year later. In 1972, the last holdout among daytime network programs converted to color, resulting in the first completely all-color network season.

Early color sets were either floor-standing console models or tabletop versions nearly as bulky and heavy, so in practice they remained firmly anchored in one place. The introduction of GE's relatively compact and lightweight Porta-Color set in the spring of 1966 made watching color television a more flexible and convenient proposition. In 1972, sales of color sets finally surpassed sales of black-and-white sets.

Color broadcasting in Europe was also not standardized on the PAL format until the 1960s.

By the mid-1970s, the only stations broadcasting in black-and-white were a few high-numbered UHF stations in small markets and a handful of low-power repeater stations in even smaller markets, such as vacation spots. By 1979, even the last of these had converted to color and by the early 1980s, black-and-white sets had been pushed into niche markets, notably low-power uses, small portable sets, or use as video monitor screens in lower-cost consumer equipment. By the late 1980s, even these areas switched to color sets.

Digital television

Digital television (DTV) is the transmission of audio and video by digitally processed and multiplexed signal, in contrast to the totally analog and channel separated signals used by analog television. Digital TV can support more than one program in the same channel bandwidth. It is an innovative service that represents the first significant evolution in television technology since color television in the 1950s.

Digital TV's roots have been tied very closely to the availability of inexpensive, high-performance computers. It wasn't until the 1990s that digital TV became a real possibility.

In the mid-1980s Japanese consumer electronics firm Sony Corporation developed HDTV technology and the equipment to record at such resolution, and the MUSE analog format proposed by NHK, a Japanese broadcaster, was seen as a pacesetter that threatened to eclipse U.S. electronics companies. Sony's system produced images at 1125-line resolution (or in digital terms, 1875x1125, close to the resolution of Full HD video) Until June 1990, the Japanese MUSE standard—based on an analog system—was the front-runner among the more than 23 different technical concepts under consideration. Then, an American company, General Instrument, demonstrated the feasibility of a digital television signal. This breakthrough was of such significance that the FCC was persuaded to delay its decision on an ATV standard until a digitally based standard could be developed.

In March 1990, when it became clear that a digital standard was feasible, the FCC made a number of critical decisions. First, the Commission declared that the new ATV standard must be more than an enhanced analog signal, but be able to provide a genuine HDTV signal with at least twice the resolution of existing television images. Then, to ensure that viewers who did not wish to buy a new digital television set could continue to receive conventional television broadcasts, it dictated that the new ATV standard must be capable of being "simulcast" on different channels. The new ATV standard also allowed the new DTV signal to be based on entirely new design principles. Although incompatible with the existing NTSC standard, the new DTV standard would be able to incorporate many improvements.

The final standard adopted by the FCC did not require a single standard for scanning formats, aspect ratios, or lines of resolution. This outcome resulted from a dispute between the consumer electronics industry (joined by some broadcasters) and the computer industry (joined by the film industry and some public interest groups) over which of the two scanning processes—interlaced or progressive—is superior. Interlaced scanning, which is used in televisions worldwide, scans even-numbered lines first, then odd-numbered ones. Progressive scanning, which is the format used in computers, scans lines in sequences, from top to bottom. The computer industry argued that progressive scanning is superior because it does not "flicker" in the manner of interlaced scanning. It also argued that progressive scanning enables easier connections with the Internet, and is more cheaply converted to interlaced formats than vice versa. The film industry also supported progressive scanning because it offers a more efficient means of converting filmed programming into digital formats. For their part, the consumer electronics industry and broadcasters argued that interlaced scanning was the only technology that could transmit the highest quality pictures then feasible, that is, 1080 lines per picture and 1920 pixels per line. William F. Schreiber, who was a director of the Advanced Television Research Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1983 until his retirement in 1990, thought that the continued advocacy of interlaced equipment originated from consumer electronics companies that were trying to get back the substantial investments they made in the interlaced technology.

Digital television transition started in the late 2000s. All the governments across the world set the deadline for analog shutdown by the 2010s. Initially the adoption rate was low. But soon, more and more households were converting to digital televisions. The transition was expected to be complete worldwide by the mid to late 2010s.

Smart television

Advent of digital television allowed innovations like smart TVs. A smart television, sometimes referred to as connected TV or hybrid television, is a television set with integrated Internet and Web 2.0 features, and is an example of technological convergence between computers and television sets and set-top boxes. Besides the traditional functions of television sets and set-top boxes provided through traditional broadcasting media, these devices can also provide Internet TV, online interactive media, over-the-top content, as well as on-demand streaming media, and home networking access. These TVs come pre-loaded with an operating system.

Smart TV should not to be confused with Internet TV, IPTV or with Web TV. Internet television refers to the receiving television content over internet instead of traditional systems (terrestrial, cable and satellite) (although internet itself is received by these methods). Internet Protocol television (IPTV) is one of the emerging Internet television technology standards for use by television broadcasters. Web television (WebTV) is a term used for programs created by a wide variety of companies and individuals for broadcast on Internet TV.

A first patent was filed in 1994 (and extended the following year) for an "intelligent" television system, linked with data processing systems, by means of a digital or analog network. Apart from being linked to data networks, one key point is its ability to automatically download necessary software routines, according to a user's demand, and process their needs.

Major TV manufacturers have announced production of smart TVs only, for middle-end and high-end TVs in 2015.

3D television

Stereoscopic 3D television was demonstrated for the first time on August 10, 1928, by John Logie Baird in his company's premises at 133 Long Acre, London. Baird pioneered a variety of 3D television systems using electro-mechanical and cathode-ray tube techniques. The first 3D TV was produced in 1935. The advent of digital television in the 2000s greatly improved 3D TVs.

Although 3D TV sets are quite popular for watching 3D home media such as on Blu-ray discs, 3D programming has largely failed to make inroads among the public. Many 3D television channels that started in the early 2010s were shut down by the mid-2010s.

Terrestrial television

Overview

Programming is broadcast by television stations, sometimes called "channels", as stations are licensed by their governments to broadcast only over assigned channels in the television band. At first, terrestrial broadcasting was the only way television could be widely distributed, and because bandwidth was limited, i.e., there were only a small number of channels available, government regulation was the norm.

Canada

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) adopted the American NTSC 525-line B/W 60 field per second system as its broadcast standard. It began television broadcasting in Canada in September 1952. The first broadcast was on September 6, 1952 from its Montreal station CBFT. The premiere broadcast was bilingual, spoken in English and French. Two days later, on September 8, 1952, the Toronto station CBLT went on the air. This became the English-speaking flagship station for the country, while CBFT became the French-language flagship after a second English-language station was licensed to CBC in Montreal later in the decade. The CBC's first privately owned affiliate television station, CKSO in Sudbury, Ontario, launched in October 1953 (at the time, all private stations were expected to affiliate with the CBC, a condition that was relaxed in 1960–61 when CTV, Canada's second national English-language network, was formed).

Czechoslovakia

In former Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia) the first experimental television sets were produced in 1948. In the same year the first test television transmission was performed. Regular television broadcasts in Prague area started on May 1, 1953. Television service expanded in the following years as new studios were built in Ostrava, Bratislava, Brno and Košice. By 1961 more than a million citizens owned a television set. The second channel of the state-owned Czechoslovak Television started broadcasting in 1970.

Preparations for color transmissions in the PAL color system started in the second half of the 1960s. However, due to the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and the following normalization period, the broadcaster was ultimately forced to adopt the SECAM color system used by the rest of the Eastern Bloc. Regular color transmissions eventually started in 1973, with television studios using PAL equipment and the output signal only being transcoded to SECAM at transmitter sites.

After the Velvet Revolution, it was decided to switch to the PAL standard. The new OK3 channel was launched by Czechoslovak Television in May 1990 and broadcast in the format from the very start. The remaining channels switched to PAL by July 1, 1992. Commercial television didn't start broadcasting until after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia.

France

The first experiments in television broadcasting began in France in the 1930s, although the French did not immediately employ the new technology.

In November 1929, Bernard Natan established France's first television company, Télévision-Baird-Natan. On April 14, 1931, there took place the first transmission with a thirty-line standard by René Barthélemy. On December 6, 1931, Henri de France created the Compagnie Générale de Télévision (CGT). In December 1932, Barthélemy carried out an experimental program in black and white (definition: 60 lines) one hour per week, "Paris Télévision", which gradually became daily from early 1933.

The first official channel of French television appeared on February 13, 1935, the date of the official inauguration of television in France, which was broadcast in 60 lines from 8:15 to 8:30 pm. The program showed the actress Béatrice Bretty in the studio of Radio-PTT Vision at 103 rue de Grenelle in Paris. The broadcast had a range of 100 km (62 mi). On November 10, George Mandel, Minister of Posts, inaugurated the first broadcast in 180 lines from the transmitter of the Eiffel Tower. On the 18th, Susy Wincker, the first announcer since the previous June, carried out a demonstration for the press from 5:30 to 7:30 pm. Broadcasts became regular from January 4, 1937 from 11:00 to 11:30 am and 8:00 to 8:30 pm during the week, and from 5:30 to 7:30 pm on Sundays. In July 1938, a decree defined for three years a standard of 455 lines VHF (whereas three standards were used for the experiments: 441 lines for Gramont, 450 lines for the Compagnie des Compteurs and 455 for Thomson). In 1939, there were about only 200 to 300 individual television sets, some of which were also available in a few public places.

With the entry of France into World War II the same year, broadcasts ceased and the transmitter of the Eiffel Tower was sabotaged. On September 3, 1940, French television was seized by the German occupation forces. A technical agreement was signed by the Compagnie des Compteurs and Telefunken, and a financing agreement for the resuming of the service is signed by German Ministry of Post and Radiodiffusion Nationale (Vichy's radio). On May 7, 1943 at 3:00 evening broadcasts. The first broadcast of Fernsehsender Paris (Paris Télévision) was transmitted from rue Cognac-Jay. These regular broadcasts (51⁄4 hours a day) lasted until August 16, 1944. One thousand 441-line sets, most of which were installed in soldiers' hospitals, picked up the broadcasts. These Nazi-controlled television broadcasts from the Eiffel Tower in Paris were able to be received on the south coast of England by R.A.F. and BBC engineers, who photographed the station identification image direct from the screen.

In 1944, René Barthélemy developed an 819-line television standard. During the years of occupation, Barthélemy reached 1015 and even 1042 lines. On October 1, 1944, television service resumed after the liberation of Paris. The broadcasts were transmitted from the Cognacq-Jay studios. In October 1945, after repairs, the transmitter of the Eiffel Tower was back in service. On November 20, 1948, François Mitterrand decreed a broadcast standard of 819 lines; broadcasting began at the end of 1949 in this definition. Besides France, this standard was later adopted by Algeria, Monaco, and Morocco. Belgium and Luxembourg used a modified version of this standard with bandwidth narrowed to 7 MHz.

Germany

Electromechanical broadcasts began in Germany in 1929, but were without sound until 1934. Network electronic service started on March 22, 1935, on 180 lines using telecine transmission of film, intermediate film system, or cameras using the Nipkow Disk. Transmissions using cameras based on the iconoscope began on January 15, 1936. The Berlin Summer Olympic Games were televised, using both all-electronic iconoscope-based cameras and intermediate film cameras, to Berlin and Hamburg in August 1936. Twenty-eight public television rooms were opened for anybody who did not own a television set. The Germans had a 441-line system on the air in February 1937, and during World War II brought it to France, where they broadcast from the Eiffel Tower.

After the end of World War II, the victorious Allies imposed a general ban on all radio and television broadcasting in Germany. Radio broadcasts for information purposes were soon permitted again, but television broadcasting was allowed to resume only in 1948.

In East Germany, the head of broadcasting in the Soviet occupation zone, Hans Mahler, predicted in 1948 that in the near future 'a new and important technical step forward in the field of broadcasting in Germany will begin its triumphant march: television.' In 1950, the plans for a nationwide television service got off the ground, and a Television Centre in Berlin was approved. Transmissions began on December 21, 1952 using the 625-line standard developed in the Soviet Union in 1944, although at that time there were probably no more than 75 television receivers capable of receiving the programming.

In West Germany, the British occupation forces as well as NWDR (Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk), which had started work in the British zone straight after the war, agreed to the launch of a television station. Even before this, German television specialists had agreed on 625 lines as the future standard. This standard had narrower channel bandwidth (7 MHz) compared to the Soviet specification (8 MHz), allowing three television channels to fit into the VHF I band. In 1963 a second broadcaster (ZDF) started. Commercial stations began programming in the 1980s.

When color was introduced, West Germany (1967) chose a variant of the NTSC color system, modified by Walter Bruch and called PAL. East Germany (1969) accepted the French SECAM system, which was used in Eastern European countries. With the reunification of Germany, it was decided to switch to the PAL color system. The system was changed in December 1990.

Italy

In Italy, the first experimental tests on television broadcasts were made in Turin since 1934. The city already hosted the Center for Management of the EIAR (lately renamed as RAI) at the premises of the Theatre of Turin. Subsequently, the EAIR established offices in Rome and Milan. On July 22, 1939 comes into operation in Rome the first television transmitter at the EIAR station, which performed a regular broadcast for about a year using a 441-line system that was developed in Germany. In September of the same year, a second television transmitter was installed in Milan, making experimental broadcasts during major events in the city.

The broadcasts were suddenly ended on May 31, 1940, by order of the government, allegedly because of interferences encountered in the first air navigation systems. Also, the imminent participation in the war is believed to have played a role in this decision. EIAR transmitting equipment was relocated to Germany by the German troops. Lately, it was returned to Italy.

The first official television broadcast began on January 3, 1954 by the RAI.

Japan

Television broadcasting in Japan started on August 28, 1953, making the country one of the first in the world with an experimental television service. The first television tests were conducted as early as 1926 using a combined mechanical Nipkow disk and electronic Braun tube system, later switching to an all-electronic system in 1935 using a domestically developed iconoscope system. In spite of that, because of the beginning of World War II in the Pacific region, this first full-fledged TV broadcast experimentation lasted only a few months. Regular television broadcasts would eventually start in 1953.

In 1979, NHK first developed a consumer high-definition television with a 5:3 display aspect ratio. The system, known as Hi-Vision or MUSE after its Multiple sub-Nyquist sampling encoding for encoding the signal, required about twice the bandwidth of the existing NTSC system but provided about four times the resolution (1080i/1125 lines). Satellite test broadcasts started in 1989, with regular testing starting in 1991 and regular broadcasting of BS-9ch commenced on November 25, 1994, which featured commercial and NHK television programming.

Sony first demonstrated a wideband analog high-definition television system HDTV capable video camera, monitor and video tape recorder (VTR) in April 1981 at an international meeting of television engineers in Algiers. The Sony HDVS range was launched in April 1984, with the HDC-100 camera, HDV-100 video recorder and HDS-100 video switcher all working in the 1125-line component video format with interlaced video and a 5:3 aspect ratio.

Mexico

The first testing television station in Mexico signed on in 1935. When KFMB-TV in San Diego signed on in 1949, Baja California became the first state to receive a commercial television station over the air. Within a year, the Mexican government would adopt the U.S. NTSC 525-line B/W 60-field-per-second system as the country's broadcast standard. In 1950, the first commercial television station within Mexico, XHTV in Mexico City, signed on the air, followed by XEW-TV in 1951 and XHGC in 1952. Those three were not only the first television stations in the country, but also the flagship stations of Telesistema Mexicano, which was formed in 1955. That year, Emilio Azcárraga Vidaurreta, who had signed on XEW-TV, entered into a partnership with Rómulo O'Farrill who had signed on XHTV, and Guillermo González Camarena, who had signed on XHGC. The earliest 3D television broadcasts in the world were broadcast over XHGC in 1954. Color television was introduced in 1962, also over XHGC-TV. One of Telesistema Mexicano's earliest broadcasts as a network, over XEW-TV, on June 25, 1955, was the first international North American broadcast in the medium's history, and was jointly aired with NBC in the United States, where it aired as the premiere episode of Wide Wide World, and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Except for a brief period between 1969 and 1973, nearly every commercial television station in Mexico, with exceptions in the border cities, was expected to affiliate with a subnetwork of Telesistema Mexicano or its successor, Televisa (formed by the 1973 merger of Telesistema Mexicano and Television Independiente de Mexico). This condition would not be relaxed for good until 1993, when Imevision was privatized to become TV Azteca.

Soviet Union (U.S.S.R.)

The Soviet Union began offering 30-line electromechanical test broadcasts in Moscow on October 31, 1931, and a commercially manufactured television set in 1932.

First electronic television system on 180 lines at 25 fps was created in the beginning of 1935 in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). In September 1937 the experimental Leningrad TV Center (OLTC) was put in action. OLTC worked with 240 lines at 25 fps progressive scan.

In Moscow, experimental transmissions of electronic television took place on March 9, 1937, using equipment manufactured by RCA. Regular broadcasting began on December 31, 1938. It was quickly realized that 343 lines of resolution offered by this format would have become insufficient in the long run, thus a specification for 441-line format at 25 fps interlaced was developed in 1940.

Television broadcasts were suspended during Great Patriotic War. In 1944, while the war was still raging, a new standard, offering 625 lines of vertical resolution was prepared. This format was ultimately accepted as a national standard.

The transmissions in 625-line format started in Moscow on November 4, 1948. Regular broadcasting began on June 16, 1949. Details for this standard were formalized in 1955 specification called GOST 7845-55, basic parameters for black-and-white television broadcast. In particular, frame size was set to 625 lines, frame rate to 25 frames/s interlaced, and video bandwidth to 6 MHz. These basic parameters were accepted by most countries having 50 Hz mains frequency and became the foundation of television systems presently known as PAL and SECAM.

Starting in 1951, broadcasting in the 625-line standard was introduced in other major cities of the Soviet Union.

Color television broadcast started in 1967, using SECAM color system.

Turkey

The first Turkish television channel, ITU TV, was launched in 1952. The first national television is TRT 1 and was launched in 1964. Color television was introduced in 1981. Before 1989 there was the only channel, the state broadcasting company TRT, and it broadcast in several times of the dateline. Turkey's first private television channel Star started it broadcast on 26 May 1989. Until then there was only one television channel controlled by the state, but with the wave of liberalization, privately owned broadcasting began. Turkey's television market is defined by a handful of big channels, led by Kanal D, ATV and Show, with 14%, 10% and 9.6% market share, respectively. The most important reception platforms are terrestrial and satellite, with almost 50% of homes using satellite (of these 15% were pay services) at the end of 2009. Three services dominate the multi-channel market: the satellite platforms Digitürk and D-Smart and the cable TV service Türksat.

United Kingdom

The first British television broadcast was made by Baird Television's electromechanical system over the BBC radio transmitter in September 1929. Baird provided a limited amount of programming five days a week by 1930. During this time, Southampton earned the distinction of broadcasting the first-ever live television interview, which featured Peggy O'Neil, an actress and singer from Buffalo, New York. On August 22, 1932, BBC launched its own regular service using Baird's 30-line electromechanical system, continuing until September 11, 1935.

On November 2, 1936, the BBC began transmitting the world's first public regular high-definition service from the Victorian Alexandra Palace in north London. It therefore claims to be the birthplace of TV broadcasting as we know it today. It was a dual-system service, alternating between Marconi-EMI's 405-line standard and Baird's improved 240-line standard, from Alexandra Palace in London. The BBC Television Service continues to this day.

The government, on advice from a special advisory committee, decided that Marconi-EMI's electronic system gave the superior picture, and the Baird system was dropped in February 1937. TV broadcasts in London were on the air an average of four hours daily from 1936 to 1939. There were 12,000 to 15,000 receivers. Some sets in restaurants or bars might have 100 viewers for sport events (Dunlap, p56). The outbreak of the Second World War caused the BBC service to be abruptly suspended on September 1, 1939, at 12:35 pm, after a Mickey Mouse cartoon and test signals were broadcast, so that transmissions could not be used as a beacon to guide enemy aircraft to London. It resumed, again from Alexandra Palace on June 7, 1946 after the end of the war, began with a live programme that opened with the line "Good afternoon everybody. How are you? Do you remember me, Jasmine Bligh?" and was followed by the same Mickey Mouse cartoon broadcast on the last day before the war. At the end of 1947 there were 54,000 licensed television receivers, compared with 44,000 television sets in the United States at that time.

The first transatlantic television signal was sent in 1928 from London to New York by the Baird Television Development Company/Cinema Television, although this signal was not broadcast to the public. The first live satellite signal to Britain from the United States was broadcast via the Telstar satellite on July 23, 1962.

The first live broadcast from the European continent was made on August 27, 1950.

United States

WRGB claims to be the world's oldest television station, tracing its roots to an experimental station founded on January 13, 1928, broadcasting from the General Electric factory in Schenectady, NY, under the call letters W2XB. It was popularly known as "WGY Television" after its sister radio station. Later in 1928, General Electric started a second facility, this one in New York City, which had the call letters W2XBS and which today is known as WNBC. The two stations were experimental in nature and had no regular programming, as receivers were operated by engineers within the company. The image of a Felix the Cat doll rotating on a turntable was broadcast for 2 hours every day for several years as new technology was being tested by the engineers.

The first regularly scheduled television service in the United States began on July 2, 1928, fifteen months before the United Kingdom. The Federal Radio Commission authorized C. F. Jenkins to broadcast from experimental station W3XK in Wheaton, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C. For at least the first eighteen months, 48-line silhouette images from motion picture film were broadcast, although beginning in the summer of 1929 he occasionally broadcast in halftones.

Hugo Gernsback's New York City radio station began a regular, if limited, schedule of live television broadcasts on August 14, 1928, using 48-line images. Working with only one transmitter, the station alternated radio broadcasts with silent television images of the station's call sign, faces in motion, and wind-up toys in motion. Speaking later that month, Gernsback downplayed the broadcasts, intended for amateur experimenters. "In six months we may have television for the public, but so far we have not got it." Gernsback also published Television, the world's first magazine about the medium.

General Electric's experimental station in Schenectady, New York, on the air sporadically since January 13, 1928, was able to broadcast reflected-light, 48-line images via shortwave as far as Los Angeles, and by September was making four television broadcasts weekly. It is considered to be the direct predecessor of current television station WRGB. The Queen's Messenger, a one-act play broadcast on September 11, 1928, was the world's first live drama on television.

Radio giant RCA began daily experimental television broadcasts in New York City in March 1929 over station W2XBS, the predecessor of current television station WNBC. The 60-line transmissions consisted of pictures, signs, and views of persons and objects. Experimental broadcasts continued to 1931.

General Broadcasting System's WGBS radio and W2XCR television aired their regular broadcasting debut in New York City on April 26, 1931, with a special demonstration set up in Aeolian Hall at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-fourth Street. Thousands waited to catch a glimpse of the Broadway stars who appeared on the six-inch (15 cm) square image, in an evening event to publicize a weekday programming schedule offering films and live entertainers during the four-hour daily broadcasts. Appearing were boxer Primo Carnera, actors Gertrude Lawrence, Louis Calhern, Frances Upton and Lionel Atwill, WHN announcer Nils Granlund, the Forman Sisters, and a host of others.

CBS's New York City station W2XAB began broadcasting their first regular seven-day-a-week television schedule on July 21, 1931, with a 60-line electromechanical system. The first broadcast included Mayor Jimmy Walker, the Boswell Sisters, Kate Smith, and George Gershwin. The service ended in February 1933. Don Lee Broadcasting's station W6XAO in Los Angeles went on the air in December 1931. Using the UHF spectrum, it broadcast a regular schedule of filmed images every day except Sundays and holidays for several years.

By 1935, low-definition electromechanical television broadcasting had ceased in the United States except for a handful of stations run by public universities that continued to 1939. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) saw television in the continual flux of development with no consistent technical standards, hence all such stations in the U.S. were granted only experimental and non-commercial licenses, hampering television's economic development. Just as importantly, Philo Farnsworth's August 1934 demonstration of an all-electronic system at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia pointed out the direction of television's future.

On June 15, 1936, Don Lee Broadcasting began a one-month-long demonstration of high definition (240+ line) television in Los Angeles on W6XAO (later KTSL, now KCBS-TV) with a 300-line image from motion picture film. By October, W6XAO was making daily television broadcasts of films. By 1934 RCA increased the definition to 343 interlaced lines and the frame rate to 30 per second. On July 7, 1936 RCA and its subsidiary NBC demonstrated in New York City a 343-line electronic television broadcast with live and film segments to its licensees, and made its first public demonstration to the press on November 6. Irregularly scheduled broadcasts continued through 1937 and 1938. Regularly scheduled electronic broadcasts began in April 1938 in New York (to the second week of June, and resuming in August) and Los Angeles. NBC officially began regularly scheduled television broadcasts in New York on April 30, 1939, with a broadcast of the opening of the 1939 New York World's Fair.

In 1937 RCA raised the frame definition to 441 lines, and its executives petitioned the FCC for approval of the standard. By June 1939, regularly scheduled 441-line electronic television broadcasts were available in New York City and Los Angeles, and by November on General Electric's station in Schenectady. From May through December 1939, the New York City NBC station (W2XBS) of RCA broadcast twenty to fifty-eight hours of programming per month, Wednesday through Sunday of each week. The programming was 33% news, 29% drama, and 17% educational programming, with an estimated 2,000 receiving sets by the end of the year, and an estimated audience of five to eight thousand. A remote truck could cover outdoor events from up to 10 miles (16 km) away from the transmitter, which was located atop the Empire State Building. Coaxial cable was used to cover events at Madison Square Garden. The coverage area for reliable reception was a radius of 40 to 50 miles (80 km) from the Empire State Building, an area populated by more than 10,000,000 people.

The FCC adopted NTSC television engineering standards on May 2, 1941, calling for 525 lines of vertical resolution, 30 frames per second with interlaced scanning, 60 fields per second, and sound carried by frequency modulation. Sets sold since 1939 that were built for slightly lower resolution could still be adjusted to receive the new standard. (Dunlap, p31). The FCC saw television ready for commercial licensing, and the first such licenses were issued to NBC- and CBS-owned stations in New York on July 1, 1941, followed by Philco's station WPTZ in Philadelphia.

In the U.S., the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) allowed stations to broadcast advertisements beginning in July 1941, but required public service programming commitments as a requirement for a license. By contrast, the United Kingdom chose a different route, imposing a television license fee on owners of television reception equipment to fund the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), which had public service as part of its royal charter.

The first official, paid advertising to appear on American commercial television occurred on the afternoon of July 1, 1941, over New York station WNBT (now WNBC) before a baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies. The announcement for Bulova watches, for which the company paid anywhere from $4.00 to $9.00 (reports vary), displayed a WNBT test pattern modified to look like a clock with the hands showing the time. The Bulova logo, with the phrase "Bulova Watch Time", was shown in the lower right-hand quadrant of the test pattern while the second hand swept around the dial for one minute.

After the U.S. entry into World War II, the FCC reduced the required minimum air time for commercial television stations from 15 hours per week to 4 hours. Most TV stations suspended broadcasting; of the ten original television stations only six continued through the war. On the few that remained, programs included entertainment such as boxing and plays, events at Madison Square Garden, and illustrated war news as well as training for air raid wardens and first aid providers. In 1942, there were 5,000 sets in operation, but production of new TVs, radios, and other broadcasting equipment for civilian purposes was suspended from April 1942 to August 1945 (Dunlap).

By 1947, when there were 40 million radios in the U.S., there were about 44,000 television sets (with probably 30,000 in the New York area). Regular network television broadcasts began on NBC on a three-station network linking New York with the Capital District and Philadelphia in 1944; on the DuMont Television Network in 1946, and on CBS and ABC in 1948.

Following the rapid rise of television after the war, the Federal Communications Commission was flooded with applications for television station licenses. With more applications than available television channels, the FCC ordered a freeze on processing station applications in 1948 that remained in effect until April 14, 1952.

By 1949, the networks stretched from New York to the Mississippi River, and by 1951 to the West Coast. Commercial color television broadcasts began on CBS in 1951 with a field-sequential color system that was suspended four months later for technical and economic reasons. The television industry's National Television System Committee (NTSC) developed a color television system based on RCA technology that was compatible with existing black and white receivers, and commercial color broadcasts reappeared in 1953.

With the widespread adoption of cable across the United States in the 1970s and 80s, terrestrial television broadcasts have been in decline; in 2013 it was estimated that about 7% of US households used an antenna. A slight increase in use began around 2010 due to a switchover to digital terrestrial television broadcasts, which offer pristine image quality over very large areas, and offered an alternate to CATV for cord cutters.

Cable television

Cable television is a system of broadcasting television programming to paying subscribers via radio frequency (RF) signals transmitted through coaxial cables or light pulses through fiber-optic cables. This contrasts with traditional terrestrial television, in which the television signal is transmitted over the air by radio waves and received by a television antenna attached to the television. FM radio programming, high-speed Internet, telephone service, and similar non-television services may also be provided through these cables.

The abbreviation CATV is often used for cable television. It originally stood for "community access television" or "community antenna television", from cable television's origins in 1948: in areas where over-the-air reception was limited by distance from transmitters or mountainous terrain, large "community antennas" were constructed, and cable was run from them to individual homes. The origins of cable broadcasting are even older as radio programming was distributed by cable in some European cities as far back as 1924.

Early cable television was analog, but since the 2000s all cable operators have switched to, or are in the process of switching to, digital cable television.

Satellite television

Overview

Satellite television is a system of supplying television programming using broadcast signals relayed from communication satellites. The signals are received via an outdoor parabolic reflector antenna usually referred to as a satellite dish and a low-noise block downconverter (LNB). A satellite receiver then decodes the desired television programme for viewing on a television set. Receivers can be external set-top boxes, or a built-in television tuner. Satellite television provides a wide range of channels and services, especially to geographic areas without terrestrial television or cable television.

The most common method of reception is direct-broadcast satellite television (DBSTV), also known as "direct to home" (DTH). In DBSTV systems, signals are relayed from a direct broadcast satellite on the Ku wavelength and are completely digital. Satellite TV systems formerly used systems known as television receive-only. These systems received analog signals transmitted in the C-band spectrum from FSS type satellites, and required the use of large dishes. Consequently, these systems were nicknamed "big dish" systems, and were more expensive and less popular.

The direct-broadcast satellite television signals were earlier analog signals and later digital signals, both of which require a compatible receiver. Digital signals may include high-definition television (HDTV). Some transmissions and channels are free-to-air or free-to-view, while many other channels are pay television requiring a subscription. In 1945 British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke proposed a worldwide communications system that would function by means of three satellites equally spaced apart in earth orbit. This was published in the October 1945 issue of the Wireless World magazine and won him the Franklin Institute's Stuart Ballantine Medal in 1963.

The first satellite television signals from Europe to North America were relayed via the Telstar satellite over the Atlantic ocean on July 23, 1962. The signals were received and broadcast in North American and European countries and watched by over 100 million. Launched in 1962, the Relay 1 satellite was the first satellite to transmit television signals from the US to Japan. The first geosynchronous communication satellite, Syncom 2, was launched on July 26, 1963.