From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Peak uranium is the point in time that the maximum global uranium production rate is reached. After that peak, according to Hubbert peak theory, the rate of production enters a terminal decline. While uranium is used in nuclear weapons, its primary use is for energy generation via nuclear fission of the uranium-235 isotope in a nuclear power reactor.

Each kilogram of uranium-235 fissioned releases the energy equivalent of

millions of times its mass in chemical reactants, as much energy as

2700 tons of coal, but uranium-235 accounts for only 0.7% of the mass of natural uranium. While Uranium-235 can be "bred" from 234

U, a natural decay product of 238

U present at 55 ppm in all natural uranium samples,

Uranium-235 is ultimately a finite non-renewable resource. Due to the currently low price of uranium, the majority of commercial light water reactors operate on a "once through fuel cycle" which leaves virtually all the energy contained in the original 238

U - which makes up over 99% of natural uranium - unused. Nuclear reprocessing

is a technology currently used at industrial scale in France, Russia

and Japan, which can recover part of that energy by producing MOX fuel or Remix Fuel

for use in conventional power generating light water reactors. However,

at current uranium prices, this is widely deemed uneconomical if only

the "input" side is considered.

Advances in breeder reactor technology could allow the current reserves of uranium to provide power for humanity for billions of years, thus making nuclear power a sustainable energy.

However, in 2010 the International Panel on Fissile Materials said

"After six decades and the expenditure of the equivalent of tens of

billions of dollars, the promise of breeder reactors remains largely

unfulfilled and efforts to commercialize them have been steadily cut

back in most countries."

But in 2016, the Russian BN-800 fast-neutron breeder reactor started producing commercially at full power (800 MWe), joining the previous BN-600. As of 2020, the Chinese CFR-600 is under construction after the success of the China Experimental Fast Reactor,

based on the BN-800. These reactors are currently generating mostly

electricity rather than new fuel because the abundance and low price of

mined and reprocessed uranium oxide makes breeding uneconomical, but

they can switch to breed new fuel and close the cycle as needed.

The CANDU reactor which was designed to be fueled with natural uranium is capable of using spent fuel from Light Water Reactors as fuel, since it contains more fissile material

than natural uranium. Research into "DUPIC" - direct use of PWR spent

fuel in CANDU type reactors - is ongoing and could increase the

usability of fuel without the need for reprocessing.

M. King Hubbert created his peak theory in 1956 for a variety of finite resources such as coal, oil, and natural gas.

He and others since have argued that if the nuclear fuel cycle can be

closed, uranium could become equivalent to renewable energy sources as

concerns its availability. Breeding and nuclear reprocessing

potentially would allow the extraction of the largest amount of energy

from natural uranium. However, only a small amount of uranium is

currently being bred into plutonium and only a small amount of fissile

uranium and plutonium is being recovered from nuclear waste worldwide.

Furthermore, the technologies to eliminate the waste in the nuclear fuel

cycle do not yet exist. Since the nuclear fuel cycle is effectively not closed, Hubbert peak theory may be applicable.

Pessimistic predictions of future high-grade uranium production

operate on the thesis that either the peak has already occurred in the

1980s or that a second peak may occur sometime around 2035.

As of 2017, identified uranium reserves recoverable at US$130/kg

were 6.14 million tons (compared to 5.72 million tons in 2015). At the

rate of consumption in 2017, these reserves are sufficient for slightly

over 130 years of supply. The identified reserves as of 2017 recoverable

at US$260/kg are 7.99 million tons (compared to 7.64 million tons in

2015).

Optimistic predictions of nuclear fuel supply are based upon one of three possible scenarios.

- LWRs only consume about half of one percent of their uranium fuel while fast breeder reactors will consume closer to 99%. Currently, more than 80% of the World's reactors are Light Water Reactors (LWRs).

- Current reserves of uranium are about 5.3 million tons.

Theoretically, 4.5 billion tons of uranium are available from sea water

at about 10 times the current price of uranium.

Currently no high volume seawater extraction systems exist. The Earth's

crust contains approximately 65 trillion tons of uranium, of which

about 32 thousand tons flow into oceans per year via rivers, which are

themselves fed via geological cycles of erosion, subduction and uplift.

- Thorium (3–4 times as abundant as uranium) might be used when supplies of uranium are depleted. However, in 2010, the UK's National Nuclear Laboratory

(NNL) concluded that for the short to medium term, "...the thorium fuel

cycle does not currently have a role to play," in that it is

"technically immature, and would require a significant financial

investment and risk without clear benefits," and concluded that the

benefits have been "overstated." Currently there are no commercially practical thorium reactors in operation.

If these predictions became reality, it would have the potential to increase the supply of nuclear fuel significantly.

Optimistic predictions claim that the supply is far more than demand and do not predict peak uranium.

Hubbert's peak and uranium

Uranium-235, the fissile isotope of uranium used in nuclear reactors,

makes up about 0.7% of uranium from ore. It is the only naturally

occurring isotope capable of directly generating nuclear power, and is a

finite, non-renewable resource. It is believed that its availability follows M. King Hubbert's peak theory, which was developed to describe peak oil.

Hubbert saw oil as a resource which would soon run out, but he believed

that uranium had much more promise as an energy source, and that breeder reactors and nuclear reprocessing,

which were new technologies at the time, would allow uranium to be a

power source for a very long time. The technologies Hubbert envisioned

would substantially reduce the rate of depletion of uranium-235, but

they are still more costly than the "once-through" cycle, and have not

been widely deployed to date.

If these and other more costly technologies such as seawater extraction

are used, any possible peak would occur in the very distant future.

According to the Hubbert Peak Theory, Hubbert's peaks are the

points where production of a resource, has reached its maximum, and from

then on, the rate of resource production enters a terminal decline.

After a Hubbert's peak, the rate of supply of a resource no longer

fulfills the previous demand rate. As a result of the law of supply and demand, at this point the market shifts from a buyer's market to a seller's market.

Many countries are not able to supply their own uranium demands

any longer - some of them never were - and must import uranium from

other countries. Thirteen countries have hit peak and exhausted their

economically recoverable uranium resources at current prices.

In a similar manner to every other natural metal resource, for

every tenfold increase in the cost per kilogram of uranium, there is a

three-hundredfold increase in available lower quality ores that would

then become economical. The theory could be observed in practice during the Uranium bubble of 2007

when an unprecedented price hike led to investments in the development

of uranium mining of lower quality deposits which mostly became stranded assets after uranium prices returned to a lower level.

Uranium demand

World consumption of primary energy by energy type in

terawatt-hours (TWh)

The world demand for uranium in 1996 was over 68 kilotonnes (150×106 lb) per year, and that number had been expected to increase to between 80 kilotonnes (180×106 lb) and 100 kilotonnes (220×106 lb) per year by 2025 due to the number of new nuclear power plants coming on line.

However following the shutdown of many nuclear power plants after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, demand had fallen to about 60 kilotonnes (130×106 lb) in 2015 and rose to 62.8 kilotonnes (138×106 lb) in 2017, with future forecasts uncertain.

According to Cameco Corporation, the demand for uranium is

directly linked to the amount of electricity generated by nuclear power

plants. Reactor capacity is growing slowly, reactors are being run more

productively, with higher capacity factors, and reactor power levels.

Improved reactor performance translates into greater uranium

consumption.

Nuclear power stations of 1000 megawatt electrical generation capacity require around 200 tonnes (440×103 lb)

of natural uranium per year. For example, the United States has 103

operating reactors with an average generation capacity of 950 MWe

demanded over 22 kilotonnes (49×106 lb) of natural uranium in 2005. As the number of nuclear power plants increase, so does the demand for uranium.

Another factor to consider is population growth. Electricity

consumption is determined in part by economic and population growth.

According to data from the CIA's World Factbook, the world population

currently (July 2020 est.) is more than 7.7 billion and it is increasing

by 1.167% per year. This means a growth of about 211,000 persons every

day. According to the UN, by 2050 it is estimated that the Earth's population will be 9.07 billion. 62% of the people will live in Africa, Southern Asia and Eastern Asia.

The largest energy-consuming class in the history of earth is being

produced in world's most populated countries, China and India. Both plan

massive nuclear energy expansion programs. China intends to build 32

nuclear plants with 40,000 MWe capacity by 2020. According to the World Nuclear Association,

India plans on bringing 20,000 MWe nuclear capacity on line by 2020,

and aims to supply 25% of electricity from nuclear power by 2050.

The World Nuclear Association believes nuclear energy could reduce the

fossil fuel burden of generating the new demand for electricity.

As more fossil fuels are used to supply the growing energy needs

of an increasing population, the more greenhouse gases are produced.

Some proponents of nuclear power believe that building more nuclear

power plants can reduce greenhouse emissions. For example, the Swedish utility Vattenfall

studied the full life cycle emissions of different ways to produce

electricity, and concluded that nuclear power produced 3.3 g/kWh of

carbon dioxide, compared to 400.0 for natural gas and 700.0 for coal. Another study however shows this figure to be 84–130 g of CO2/kWh,

with the figure rising dramatically as less concentrated ores are used

in the future. It uses a wider scope for consideration than other

studies including dismantling and disposal of the power station. The

study assumes diesel oil for the thermal parts of the uranium extraction

process.

As some countries are not able to supply their own needs of

uranium economically, countries have resorted to importing uranium ore

from elsewhere. For example, owners of U.S. nuclear power reactors

bought 67 million pounds (30 kt) of natural uranium in 2006. Out of that

84%, or 56 million pounds (25 kt), were imported from foreign

suppliers, according to the Energy Department.

Because of the improvements in gas centrifuge technology in the 2000s, replacing former gaseous diffusion plants, cheaper separative work units have enabled the economic production of more enriched uranium from a given amount of natural uranium, by re-enriching tails ultimately leaving a depleted uranium tail of lower enrichment. This has somewhat lowered the demand for natural uranium.

As nuclear power plants take a long time to build and refuelling

is undertaken at sporadic, predictable intervals, uranium demand is

rather predictable in the short term. It is also less dependent on

short-term economic boom-bust cycles as nuclear power has one of

strongest fixed costs to variable costs ratios (i.e. The marginal costs of running, rather than leaving idle an already constructed power plant are very low, compared to the capital costs

of construction) and it is thus nearly never advisable to leave a

nuclear power plant idle for economic reasons. However, nuclear policy

can lead to short term fluctuations in demand, as evidenced by the

German nuclear phaseout, which was decided upon by the government of Gerhard Schröder (1998-2005) reversed during the second Merkel cabinet (2009-2013) only for a reversal of that reversal to occur as a consequence of the Fukushima nuclear accident, which also led to the temporary shutdown of several German nuclear power plants.

Uranium supply

Uranium

occurs naturally in many rocks, and even in seawater. However, like

other metals, it is seldom sufficiently concentrated to be economically

recoverable.

Like any resource, uranium cannot be mined at any desired

concentration. No matter the technology, at some point it is too costly

to mine lower grade ores. One highly criticized life cycle study by Jan Willem Storm van Leeuwen

suggested that below 0.01–0.02% (100–200 ppm) in ore, the energy

required to extract and process the ore to supply the fuel, operate

reactors and dispose properly comes close to the energy gained by using

the uranium as a fissible material in the reactor. Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute who analyzed the Jan Willem Storm van Leeuwen

paper however have detailed the number of incorrect assumptions of Jan

Willem Storm van Leeuwen that led them to this evaluation, including

their assumption that all the energy used in the mining of Olympic Dam

is energy used in the mining of uranium, when that mine is

predominantly a copper mine and uranium is produced only as a

co-product, along with gold and other metals. The report by Jan Willem Storm van Leeuwen also assumes that all enrichment is done in the older and more energy intensive gaseous diffusion technology, however the less energy intensive gas centrifuge technology has produced the majority of the world's enriched uranium now for a number of decades.

An appraisal of nuclear power by a team at MIT in 2003, and updated in 2009, have stated that:

Most commentators conclude that a half century of unimpeded growth is

possible, especially since resources costing several hundred dollars per

kilogram (not estimated in the Red Book) would also be economically

usable...We believe that the world-wide supply of uranium ore is

sufficient to fuel the deployment of 1000 reactors over the next half

century.

In the early days of the nuclear industry, uranium was thought to be very scarce, so a closed fuel cycle would be needed. Fast breeder

reactors would be needed to create nuclear fuel for other power

producing reactors. In the 1960s, new discoveries of reserves, and new

uranium enrichment techniques allayed these concerns.

Mining companies usually consider concentrations greater than

0.075% (750 ppm) as ore, or rock economical to mine at current uranium

market prices.

There is around 40 trillion tons of uranium in Earth's crust, but most

is distributed at low parts per million trace concentration over its 3 *

1019 ton mass.

Estimates of the amount concentrated into ores affordable to extract

for under $130 per kg can be less than a millionth of that total.

Uranium Grades

| Source |

Concentration

|

| Very high-grade ore – 20% U |

200,000 ppm U

|

| High-grade ore – 2% U |

20,000 ppm U

|

| Low-grade ore – 0.1% U |

1,000 ppm U

|

| Very low-grade ore – 0.01% U |

100 ppm U

|

| Granite |

4–5 ppm U

|

| Sedimentary rock |

2 ppm U

|

| Earth's continental crust (av) |

2.8 ppm U

|

| Seawater |

0.003 ppm U

|

According to the OECD Redbook, the world consumed 62.8 kilotonnes (138×106 lb) of uranium in 2017 (compared to 67 kt in 2002). Of that, 59 kt was produced from primary sources, with the balance coming from secondary sources, in particular stockpiles of natural and enriched uranium, decommissioned nuclear weapons, the reprocessing of natural and enriched uranium and the re-enrichment of depleted uranium tails.

Economically extractable reserves of uranium (0.01% ore or better)

| Ore concentration |

tonnes of uranium |

Ore type

|

| >1% |

10000 |

vein deposits

|

| 0.2–1% |

2 million |

pegmatites,unconformity deposits

|

| 0.1–0.2% |

80 million |

fossil placers, sandstones

|

| 0.02–0.1% |

100 million |

lower grade fossil placers, sandstones

|

| 100–200 ppm |

2 billion |

volcanic deposits

|

The table above assumes the fuel will be used in a LWR burner.

Uranium becomes far more economical when used in a fast burner reactor

such as the Integral Fast Reactor.

Production

10 countries are responsible for 94% of all uranium extraction.

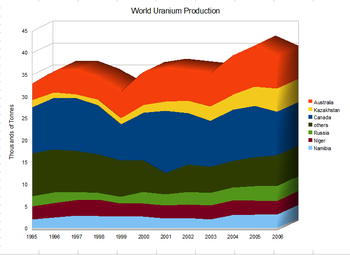

World production of uranium 1995–2006

Peak uranium refers to the peak of the entire planet's uranium production. Like other Hubbert peaks,

the rate of uranium production on Earth will enter a terminal decline.

According to Robert Vance of the OECD's Nuclear Energy Agency, the world

production rate of uranium has already reached its peak in 1980,

amounting to 69,683 tonnes (150×106 lb) of U3O8

from 22 countries. However, this is not due to lack of production

capacity. Historically, uranium mines and mills around the world have

operated at about 76% of total production capacity, varying within a

range of 57% and 89%. The low production rates have been largely

attributable to excess capacity. Slower growth of nuclear power and

competition from secondary supply significantly reduced demand for

freshly mined uranium until very recently. Secondary supplies include

military and commercial inventories, enriched uranium tails, reprocessed

uranium and mixed oxide fuel.

According to data from the International Atomic Energy Agency,

world production of mined uranium has peaked twice in the past: once,

circa 1960 in response to stockpiling for military use, and again in

1980, in response to stockpiling for use in commercial nuclear power. Up

until about 1990, the mined uranium production was in excess of

consumption by power plants. But since 1990, consumption by power plants

has outstripped the uranium being mined; the deficit being made up by

liquidation of the military (through decommissioning of nuclear weapons)

and civilian stockpiles. Uranium mining has increased since the

mid-1990s, but is still less than the consumption by power plants.

The world's top uranium producers are Kazakhstan (39% of world production), Canada (22%) and Australia (10%). Other major producers include Namibia (6.7%), Niger (6%), and Russia (5%). In 1996, the world produced 39 kilotonnes (86×106 lb) of uranium.

In 2005, the world primary mining production was 41,720 tonnes (92×106 lb) of uranium, 62% of the requirements of the power utilities. In 2017 the production had increased to 59,462 tonnes, 93% of the demand.

The balance comes from inventories held by utilities and other fuel

cycle companies, inventories held by governments, used reactor fuel that

has been reprocessed, recycled materials from military nuclear programs

and uranium in depleted uranium stockpiles.

The plutonium from dismantled Cold War nuclear weapon stockpiles will be

exhausted by 2013. The industry is trying to find and develop new

uranium mines, mainly in Canada, Australia and Kazakhstan. Those under

development in 2006 would fill half the gap.

Of the ten largest uranium mines in the world (Mc Arthur River,

Ranger, Rossing, Kraznokamensk, Olympic Dam, Rabbit Lake, Akouta, Arlit,

Beverly, and McClean Lake), by 2020, six will be depleted, two will be

in their final stages, one will be upgrading and one will be producing.

World primary mining production fell 5% in 2006 over that in

2005. The biggest producers, Canada and Australia saw falls of 15% and

20%, with only Kazakhstan showing an increase of 21%.

This can be explained by two major events that have slowed world uranium production. Canada's Cameco mine at Cigar Lake

is the largest, highest-grade uranium mine in the world. In 2006 it

flooded, and then flooded again in 2008 (after Cameco had spent $43

million – most of the money set aside – to correct the problem), causing

Cameco to push back its earliest start-up date for Cigar Lake to 2011.

Also, in March 2007, the market endured another blow when a cyclone

struck the Ranger mine in Australia, which produces 5,500 tonnes (12×106 lb)

of uranium a year. The mine's owner, Energy Resources of Australia,

declared force majeure on deliveries and said production would be

impacted into the second half of 2007.

This caused some to speculate that peak uranium has arrived.

In January 2018, McArthur River mine

in Canada suspended production, the mine was producing 7000-8000 tonnes

of Uranium per year from 2007 to 2017. The mine's owner, Cameco cited

low uranium market prices as the reason to halt production and claims

ramping production up to normal will take 18–24 months when the decision

to re-open the mine is made.

Primary sources

About

96% of the global uranium reserves are found in these ten countries:

Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Brazil, Namibia,

Uzbekistan, the United States, Niger, and Russia. Out of those the main producers are Kazakhstan (39% of world production), Canada (22%) and Australia (10%) are the major producers. In 1996, the world produced 39,000 tonnes of uranium, and in 2005, the world produced a peak of 41,720 tonnes of uranium. In 2017 this had increased to 59,462 tonnes, 93% of the world demand.

Various agencies have tried to estimate how long these primary resources will last, assuming a once-through cycle.

The European Commission said in 2001 that at the current level of

uranium consumption, known uranium resources would last 42 years. When

added to military and secondary sources, the resources could be

stretched to 72 years. Yet this rate of usage assumes that nuclear power

continues to provide only a fraction of the world's energy supply. If

electric capacity were increased six-fold, then the 72-year supply would

last just 12 years.

The world's present measured resources of uranium, economically

recoverable at a price of US$130/kg according to the industry groups Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), are enough to last for "at least a century" at current consumption rates.[62][63] According to the World Nuclear Association,

yet another industry group, assuming the world's current rate of

consumption at 66,500 tonnes of uranium per year and the world's present

measured resources of uranium (4.7–5.5 Mt) are enough to last for some 70–80 years.

Reserves

Reserves

are the most readily available resources. Resources that are known to

exist and easy to mine are called "Known conventional resources".

Resources that are thought to exist but have not been mined are

classified under "Undiscovered conventional resources".

The known uranium resources represent a higher level of assured

resources than is normal for most minerals. Further exploration and

higher prices will certainly, on the basis of present geological

knowledge, yield further resources as present ones are used up. There

was very little uranium exploration between 1985 and 2005, so the

significant increase in exploration effort that we are now seeing could

readily double the known economic resources. On the basis of analogies

with other metal minerals, a doubling of price from price levels in 2007

could be expected to create about a tenfold increase in measured

resources, over time.

Known conventional resources

Known conventional resources are "Reasonably Assured Resources" and "Estimated Additional Resources-I".

In 2006, about 4 million tons of conventional resources were

thought to be sufficient at current consumption rates for about six

decades (4.06 million tonnes at 65,000 tonnes per year).

In 2011, this was estimated to be 7 million tonnes. Exploration for

uranium has increased. From 1981 to 2007, annual exploration

expenditures grew modestly, from 4 million US$ to 7 million US$. This

skyrocketed to US$11 million in 2011. Consumption of uranium runs at around 75 000 t a year. This is less than production, and requires draw down of existing stocks.

About 96% of the global uranium reserves are found in these ten

countries: Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Brazil, Namibia,

Uzbekistan, the United States, Niger, and Russia.

The world's largest deposits of uranium are found in three countries.

Australia has just over 30% of the world's reasonably assured resources

and inferred resources of uranium – about 1.673 megatonnes (3.69×109 lb).

Kazakhstan has about 12% of the world's reserves, or about 651 kilotonnes (1.4×109 lb). And Canada has 485 kilotonnes (1,100×106 lb) of uranium, representing about 9%.

Several countries in Europe no longer mine uranium (East Germany

(1990), France (2001), Spain (2002) and Sweden (1969)); they were not

major producers.

Undiscovered conventional resources

Undiscovered

conventional resources can be broken up into two classifications

"Estimated Additional Resources-II" and "Speculative Resources".

It will take a significant exploration and development effort to

locate the remaining deposits and begin mining them. However, since the

entire earth's geography has not been explored for uranium at this time,

there is still the potential to discover exploitable resources.

The OECD Redbook cites areas still open to exploration throughout the

world. Many countries are conducting complete aeromagnetic gradiometer

radiometric surveys to get an estimate the size of their undiscovered

mineral resources. Combined with a gamma-ray survey, these methods can

locate undiscovered uranium and thorium deposits.

The U.S. Department of Energy conducted the first and only national

uranium assessment in 1980 – the National Uranium Resource Evaluation

(NURE) program.

Secondary resources

Secondary

resources are essentially recovered uranium from other sources such as

nuclear weapons, inventories, reprocessing and re-enrichment. Since

secondary resources have exceedingly low discovery costs and very low

production costs, they may have displaced a significant portion of

primary production. Secondary uranium was and is available essentially

instantly. However, new primary production will not be. Essentially,

secondary supply is a "one-time" finite supply, with the exception of

the re-processed fuel.

Uranium mining activity is cyclical, in 2009 80% of the

requirements of power utilities were supplied by mines, in 2017 this had

risen to 93%. The balance comes from inventories held by utilities and other fuel

cycle companies, inventories held by governments, used reactor fuel that

has been reprocessed, recycled materials from military nuclear programs

and uranium in depleted uranium stockpiles.

The plutonium from dismantled cold war nuclear weapon stockpiles was a major source of nuclear fuel under the "Megatons to Megawatts"

program which ended in December 2013. The industry developed new

uranium mines, especially in Kazakhstan which now attributes to 31% of

the world supply.

Inventories

Inventories are kept by a variety of organizations – government, commercial and others.

The US DOE keeps inventories for security of supply in order to cover for emergencies where uranium is not available at any price.

In the event of a major supply disruption, the department may not have

sufficient uranium to meet a severe uranium shortage in the United

States.

Decommissioning nuclear weapons

Both the US and Russia have committed to recycle their nuclear

weapons into fuel for electricity production. This program is known as

the Megatons to Megawatts Program. Down blending 500 tonnes (1,100×103 lb) of Russian weapons high enriched uranium (HEU) will result in about 15 kilotonnes (33,000×103 lb) of low enriched uranium (LEU) over 20 years. This is equivalent to about 152 kilotonnes (340×106 lb) of natural U, or just over twice annual world demand. Since 2000, 30 tonnes (66×103 lb) of military HEU is displacing about 10.6 kilotonnes (23×106 lb) of uranium oxide mine production per year which represents some 13% of world reactor requirements.

Plutonium recovered from nuclear weapons or other sources can be

blended with uranium fuel to produce a mixed-oxide fuel. In June 2000,

the US and Russia agreed to dispose of 34 kilotonnes (75×106 lb)

each of weapons-grade plutonium by 2014. The US undertook to pursue a

self-funded dual track program (immobilization and MOX). The G-7 nations

provided US$1 billion to set up Russia's program. The latter was

initially MOX specifically designed for VVER reactors, the Russian

version of the Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR), the high cost being

because this was not part of Russia's fuel cycle policy. This MOX fuel

for both countries is equivalent to about 12 kilotonnes (26×106 lb) of natural uranium. The U.S. also has commitments to dispose of 151 tonnes (330×103 lb) of non-waste HEU.

The Megatons to Megawatts program came to an end in 2013.

Reprocessing and recycling

Nuclear reprocessing,

sometimes called recycling, is one method of mitigating the eventual

peak of uranium production. It is most useful as part of a nuclear fuel cycle utilizing fast-neutron reactors since reprocessed uranium and reactor-grade plutonium both have isotopic compositions not optimal for use in today's thermal-neutron reactors. Although reprocessing of nuclear fuel is done in a few countries (France, United Kingdom, and Japan) the United States President banned reprocessing in the late 1970s due to the high costs and the risk of nuclear proliferation

via plutonium. In 2005, U.S. legislators proposed a program to

reprocess the spent fuel that has accumulated at power plants. At

present prices, such a program is significantly more expensive than

disposing spent fuel and mining fresh uranium.

Currently, there are eleven reprocessing plants in the world. Of

these, two are large-scale commercially operated plants for the

reprocessing of spent fuel elements from light water reactors with

throughputs of more than 1 kilotonne (2.2×106 lb) of uranium per year. These are La Hague, France with a capacity of 1.6 kilotonnes (3.5×106 lb) per year and Sellafield, England at 1.2 kilotonnes (2.6×106 lb) uranium per year. The rest are small experimental plants. The two large-scale commercial reprocessing plants together can reprocess 2,800 tonnes of uranium waste annually.

Most of the spent fuel

components can be recovered and recycled. About two-thirds of the U.S.

spent fuel inventory is uranium. This includes residual fissile

uranium-235 that can be recycled directly as fuel for heavy water reactors or enriched again for use as fuel in light water reactors.

Plutonium and uranium can be chemically separated from spent fuel. When used nuclear fuel is reprocessed using the de facto standard PUREX method, both plutonium and uranium are recovered separately. The spent fuel contains about 1% plutonium. Reactor-grade plutonium

contains Pu-240 which has a high rate of spontaneous fission, making it

an undesirable contaminant in producing safe nuclear weapons.

Nevertheless, nuclear weapons can be made with reactor grade plutonium.

The spent fuel is primarily composed of uranium, most of which

has not been consumed or transmuted in the nuclear reactor. At a typical

concentration of around 96% by mass in the used nuclear fuel, uranium

is the largest component of used nuclear fuel. The composition of reprocessed uranium depends on the time the fuel has been in the reactor, but it is mostly uranium-238, with about 1% uranium-235, 1% uranium-236 and smaller amounts of other isotopes including uranium-232. However, reprocessed uranium is also a waste product because it is contaminated and undesirable for reuse in reactors.

During its irradiation in a reactor, uranium is profoundly modified.

The uranium that leaves the reprocessing plant contains all the isotopes

of uranium between uranium-232 and uranium-238 except uranium-237, which is rapidly transformed into neptunium-237. The undesirable isotopic contaminants are:

- Uranium-232 (whose decay products emit strong gamma radiation making handling more difficult), and

- Uranium-234 (which is fertile material but can affect reactivity differently from uranium-238).

- Uranium-236 (which affects reactivity and absorbs neutrons without fissioning, becoming neptunium-237 which is one of the most difficult isotopes for long-term disposal in a deep geological repository)

- Daughter products of uranium-232: bismuth-212, thallium-208.

At present, reprocessing and the use of plutonium as reactor fuel is

far more expensive than using uranium fuel and disposing of the spent

fuel directly – even if the fuel is only reprocessed once.

However, nuclear reprocessing becomes more economically attractive,

compared to mining more uranium, as uranium prices increase.

The total recovery rate 5 kilotonnes (11×106 lb)/yr

from reprocessing currently is only a small fraction compared to the

growing gap between the rate demanded 64.615 kilotonnes (142.45×106 lb)/yr and the rate at which the primary uranium supply is providing uranium 46.403 kilotonnes (102.30×106 lb)/yr.

Energy Returned on Energy Invested (EROEI) on uranium

reprocessing is highly positive, though not as positive as the mining

and enrichment of uranium, and the process can be repeated. Additional

reprocessing plants may bring some economies of scale.

The main problems with uranium reprocessing are the cost of mined uranium compared to the cost of reprocessing,

nuclear proliferation risks, the risk of major policy change, the risk

of incurring large cleanup costs, stringent regulations for reprocessing

plants, and the anti-nuclear movement.

Unconventional resources

Unconventional

resources are occurrences that require novel technologies for their

exploitation and/or use. Often unconventional resources occur in

low-concentration. The exploitation of unconventional uranium requires

additional research and development efforts for which there is no

imminent economic need, given the large conventional resource base and

the option of reprocessing spent fuel. Phosphates, seawater, uraniferous coal ash, and some type of oil shales are examples of unconventional uranium resources.

Phosphates

The

soaring price of uranium may cause long-dormant operations to extract

uranium from phosphate. Uranium occurs at concentrations of 50 to 200

parts per million in phosphate-laden earth or phosphate rock.

As uranium prices increase, there has been interest in some countries

in extraction of uranium from phosphate rock, which is normally used as

the basis of phosphate fertilizers.

Worldwide, approximately 400 wet-process phosphoric acid

plants were in operation. Assuming an average recoverable content of

100 ppm of uranium, and that uranium prices do not increase so that the

main use of the phosphates are for fertilizers, this scenario would result in a maximum theoretical annual output of 3.7 kilotonnes (8.2×106 lb) U3O8.

Historical operating costs for the uranium recovery from phosphoric acid range from $48–$119/kg U3O8. In 2011, the average price paid for U3O8 in the United States was $122.66/kg.

There are 22 million tons of uranium in phosphate deposits. Recovery of uranium from phosphates is a mature technology;

it has been utilized in Belgium and the United States, but high

recovery costs limit the utilization of these resources, with estimated

production costs in the range of US$60–100/kgU including capital

investment, according to a 2003 OECD report for a new 100 tU/year

project.

Seawater

Unconventional uranium resources include up to 4,000 megatonnes (8,800×109 lb)

of uranium contained in sea water. Several technologies to extract

uranium from sea water have been demonstrated at the laboratory scale.

In the mid-1990s extraction costs were estimated at 260 USD/kgU

(Nobukawa, et al., 1994) but scaling up laboratory-level production to

thousands of tonnes is unproven and may encounter unforeseen

difficulties.

One method of extracting uranium from seawater

is using a uranium-specific nonwoven fabric as an absorbent. The total

amount of uranium recovered in an experiment in 2003 from three

collection boxes containing 350 kg of fabric was >1 kg of yellow cake

after 240 days of submersion in the ocean.

According to the OECD, uranium may be extracted from seawater using this method for about US$300/kgU.

In 2006 the same research group stated: "If 2g-U/kg-adsorbent is

submerged for 60 days at a time and used 6 times, the uranium cost is

calculated to be 88,000 JPY/kgU,

including the cost of adsorbent production, uranium collection, and

uranium purification. When an extraction 6g of U per kg of adsorbent and

20 repetitions or more becomes possible, the uranium cost reduces to

15,000 yen. This price level is equivalent to that of the highest cost

of the minable uranium. The lowest cost attainable now is 25,000 yen

with 4g-U/kg-adsorbent used in the sea area of Okinawa, with 18

repetition uses. In this case, the initial investment to collect the

uranium from seawater is 107.7 billion yen, which is 1/3 of the

construction cost of a one gigawatt nuclear power plant."

In 2012, ORNL

researchers announced the successful development of a new absorbent

material dubbed HiCap, which vastly outperforms previous best

adsorbents, which perform surface retention of solid or gas molecules,

atoms or ions. "We have shown that our adsorbents can extract five to

seven times more uranium at uptake rates seven times faster than the

world's best adsorbents", said Chris Janke, one of the inventors and a

member of ORNL's Materials Science and Technology Division. HiCap also

effectively removes toxic metals from water, according to results

verified by researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Among the other methods to recover uranium from sea water, two seem promising: algae bloom to concentrate uranium

and nanomembrane filtering.

So far, no more than a very small amount of uranium has been recovered from sea water in a laboratory.

Uraniferous coal ash

In particular, nuclear power facilities produce about 200,000 metric tons of low and intermediate level waste (LILW) and 10,000 metric tons of high level waste (HLW) (including spent fuel designated as waste) each year worldwide.

Although only several parts per million average concentration in

coal before combustion (albeit more concentrated in ash), the

theoretical maximum energy potential of trace uranium and thorium in

coal (in breeder reactors) actually exceeds the energy released by burning the coal itself, according to a study by Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

From 1965 to 1967 Union Carbide operated a mill in North Dakota, United States burning uraniferous lignite and extracting uranium from the ash. The plant produced about 150 metric tons of U3O8 before shutting down.

An international consortium has set out to explore the commercial

extraction of uranium from uraniferous coal ash from coal power

stations located in Yunnan province, China. The first laboratory scale amount of yellowcake uranium recovered from uraniferous coal ash was announced in 2007.

The three coal power stations at Xiaolongtang, Dalongtang and Kaiyuan

have piled up their waste ash. Initial tests from the Xiaolongtang ash

pile indicate that the material contains (160–180 parts per million

uranium), suggesting a

total of some 2.085 kilotonnes (4.60×106 lb) U3O8 could be recovered from that ash pile alone.

Oil shales

Some oil shales contain uranium, which may be recovered as a byproduct. Between 1946 and 1952, a marine type of Dictyonema shale was used for uranium production in Sillamäe, Estonia, and between 1950 and 1989 alum shale was used in Sweden for the same purpose.

Breeding

A breeder reactor produces more nuclear fuel than it consumes and

thus can extend the uranium supply. It typically turns the dominant

isotope in natural uranium, uranium-238, into fissile plutonium-239.

This results in hundredfold increase in the amount of energy to be

produced per mass unit of uranium, because U-238, which constitute 99.3%

of natural uranium, is not used in conventional reactors which instead

use U-235 which only represent 0.7% of natural uranium. In 1983, physicist Bernard Cohen proposed that the world supply of uranium is effectively inexhaustible, and could therefore be considered a form of renewable energy. He claims that fast breeder reactors,

fueled by naturally-replenished uranium-238 extracted from seawater,

could supply energy at least as long as the sun's expected remaining

lifespan of five billion years, making them as sustainable in fuel availability terms as renewable energy

sources. Despite this hypothesis there is no known economically viable

method to extract sufficient quantities from sea water. Experimental

techniques are under investigation.

There are two types of breeders: Fast breeders and thermal breeders.

Fast breeder

A fast breeder, in addition to consuming U-235, converts fertile U-238 into Pu-239, a fissile

fuel. Fast breeder reactors are more expensive to build and operate,

including the reprocessing, and could only be justified economically if

uranium prices were to rise to pre-1980 values in real terms. About 20 fast-neutron reactors

have already been operating, some since the 1950s, and one supplies

electricity commercially. Over 300 reactor-years of operating experience

have been accumulated. In addition to considerably extending the

exploitable fuel supply, these reactors have an advantage in that they

produce less long-lived transuranic wastes, and can consume nuclear waste from current light water reactors, generating energy in the process.

Several countries have research and development programs for improving

these reactors. For instance, one scenario in France is for half of the

present nuclear capacity to be replaced by fast breeder reactors by

2050. China, India, and Japan plan large scale utilization of breeder

reactors during the coming decades.

(Following the crisis at Japan's Fukishima Daiichi nuclear power plant

in 2011, Japan is revising its plans regarding future use of nuclear

power. (See: Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster: Energy policy implications.))

The breeding of plutonium fuel in Fast Breeder Reactors

(FBR), known as the plutonium economy, was for a time believed to be

the future of nuclear power. But many of the commercial breeder reactors

that have been built have been riddled with technical and budgetary

problems. Some sources critical of breeder reactors have gone so far to

call them the Supersonic Transport of the '80s.

Uranium turned out to be far more plentiful than anticipated, and

the price of uranium declined rapidly (with an upward blip in the

1970s). This is why the US halted their use in 1977 and the UK abandoned the idea in 1994.

Fast Breeder Reactors, are called fast because they have no moderator slowing down the neutrons (light water, heavy water or graphite)

and breed more fuel than they consume. The word 'fast' in fast breeder

thus refers to the speed of the neutrons in the reactor's core. The

higher the energy the neutrons have, the higher the breeding ratio or

the more uranium that is changed into plutonium.

Significant technical and materials problems were encountered

with FBRs, and geological exploration showed that scarcity of uranium

was not going to be a concern for some time. By the 1980s, due to both

factors, it was clear that FBRs would not be commercially competitive

with existing light water reactors. The economics of FBRs still depend

on the value of the plutonium fuel which is bred, relative to the cost

of fresh uranium. Research continues in several countries with working prototypes Phénix in France, the BN-600 reactor in Russia, and the Monju in Japan.

On February 16, 2006, the United States, France and Japan signed

an arrangement to research and develop sodium-cooled fast breeder

reactors in support of the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership. Breeder reactors are also being studied under the Generation IV reactor program.

Early prototypes have been plagued with problems. The liquid sodium

coolant is highly flammable, bursting into flames if it comes into

contact with air and exploding if it comes into contact with water.

Japan's fast breeder Monju Nuclear Power Plant

has been scheduled to re-open in 2008, 13 years after a serious

accident and fire involving a sodium leak. In 1997 France shut down its

Superphenix reactor, while the Phenix, built earlier, closed as

scheduled in 2009.

At higher uranium prices breeder reactors

may be economically justified. Many nations have ongoing breeder

research programs. China, India, and Japan plan large scale utilization

of breeder reactors during the coming decades. 300 reactor-years

experience has been gained in operating them.

As of June 2008 there are only two running commercial breeders

and the rate of reactor-grade plutonium production is very small (20

tonnes/yr). The reactor grade plutonium is being processed into MOX

fuel. Next to the rate at which uranium is being mined (46,403

tonnes/yr), this is not enough to stave off peak uranium; however, this

is only because mined and reprocessed uranium oxide is plentiful and

cheap, so breeding new fuel is uneconomical. They can switch to breed

large amounts of new fuel as needed, and many more breeding reactors can

be built in a short time span.

Thermal breeder

Thorium

is an alternate fuel cycle to uranium. Thorium is three times more

plentiful than uranium. Thorium-232 is in itself not fissile, but fertile. It can be made into fissile uranium-233 in a breeder reactor. In turn, the uranium-233 can be fissioned, with the advantage that smaller amounts of transuranics are produced by neutron capture, compared to uranium-235 and especially compared to plutonium-239.

Despite the thorium fuel cycle having a number of attractive features, development on a large scale can run into difficulties:

- The resulting U-233 fuel is expensive to fabricate.

- The U-233 chemically separated from the irradiated thorium fuel is highly radioactive.

- Separated U-233 is always contaminated with traces of U-232

- Thorium is difficult to recycle due to highly radioactive Th-228

- If the U-233 can be separated on its own, it becomes a weapons proliferation risk

- And, there are technical problems in reprocessing.

Advocates for liquid core and molten salt reactors such as LFTR claim that these technologies negate the above-mentioned thorium's disadvantages present in solid fueled reactors.

The first successful commercial reactor at the Indian Point power station in Buchanan, New York (Indian Point Unit 1) ran on Thorium. The first core did not live up to expectations.

Indian interest in thorium is motivated by their substantial

reserves. Almost a third of the world's thorium reserves are in India.

India's Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) says that it will construct a

500 MWe prototype reactor in Kalpakkam. There are plans for four

breeder reactors of 500 MWe each - two in Kalpakkam and two more in a

yet undecided location.

China has initiated a research and development project in thorium molten-salt breeder reactor technology. It was formally announced at the Chinese Academy of Sciences

(CAS) annual conference in January 2011. Its ultimate target is to

investigate and develop a thorium based molten salt breeder nuclear

system in about 20 years.

A 5 MWe research MSR is apparently under construction at Shanghai

Institute of Applied Physics (under the academy) with 2015 target

operation.

Supply-demand gap

Due

to reduction in nuclear weapons stockpiles, a large amount of former

weapons uranium was released for use in civilian nuclear reactors. As a

result, starting in 1990, a significant portion of uranium nuclear power

requirements were supplied by former weapons uranium, rather than newly

mined uranium. In 2002, mined uranium supplied only 54 percent of

nuclear power requirements.

But as the supply of former weapons uranium has been used up, mining

has increased, so that in 2012, mining provided 95 percent of reactor

requirements, and the OCED Nuclear Energy Agency and the International

Atomic Energy Agency projected that the gap in supply would be

completely erased in 2013.[

Uranium demand, mining production and deficit

| Country |

Uranium required 2006–08 |

% of world demand |

Indigenous mining production 2006 |

Deficit (-surplus)

|

United States United States |

18,918 tonnes (42×106 lb) |

29.3% |

2,000 tonnes (4.4×106 lb) |

16,918 tonnes (37×106 lb)

|

France France |

10,527 tonnes (23×106 lb) |

16.3% |

0 |

10,527 tonnes (23×106 lb)

|

Japan Japan |

7,659 tonnes (17×106 lb) |

11.8% |

0 |

7,659 tonnes (17×106 lb)

|

Russia Russia |

3,365 tonnes (7.4×106 lb) |

5.2% |

4,009 tonnes (8.8×106 lb) |

−644 tonnes (−1.4×106 lb)

|

Germany Germany |

3,332 tonnes (7.3×106 lb) |

5.2% |

68.03 tonnes (0.1500×106 lb) |

3,264 tonnes (7.2×106 lb)

|

South Korea South Korea |

3,109 tonnes (6.9×106 lb) |

4.8% |

0 |

3,109 tonnes (6.9×106 lb)

|

United Kingdom United Kingdom |

2,199 tonnes (4.8×106 lb) |

3.4% |

0 |

2,199 tonnes (4.8×106 lb)

|

| Rest of the World |

15,506 tonnes (34×106 lb) |

24.0% |

40,327 tonnes (89×106 lb) |

−24,821 tonnes (−55×106 lb)

|

| Total |

64,615 tonnes (140×106 lb) |

100.0% |

46,403 tonnes (100×106 lb) |

18,211 tonnes (40×106 lb)

|

For individual nations

Eleven countries, Germany, the Czech Republic, France, DR Congo, Gabon, Bulgaria, Tajikistan, Hungary, Romania, Spain, Portugal

and Argentina, have seen uranium production peak, and rely on imports for their nuclear programs. Other countries have reached their peak production of uranium and are currently on a decline.

- Germany – Between 1946 and 1990, SDAG Wismut, the former East German uranium mining company, produced a total of around 220 kilotonnes (490×106 lb) of uranium. During its peak, production exceeded 7 kilotonnes (15×106 lb) per year. In 1990, uranium mining was discontinued as a consequence of the German unification. The company could not compete on the world market. The production cost of its uranium was three times the world market price. West Germany remained a net uranium importer throughout its existence but ran a small scale uranium mine at Menzenschwand in the Black Forest called Krunkelbach Pit which was closed at the end of the Cold War

- India – having already hit its production peak, India is

finding itself in making a tough choice between using its modest and

dwindling uranium resources as a source to keep its weapons programs

rolling or it can use them to produce electricity. Since India has abundant thorium reserves, it is switching to nuclear reactors powered by the thorium fuel cycle.

- Sweden – Sweden started uranium production in 1965 but was never profitable. They stopped mining uranium in 1969.

Sweden then embarked on a massive project based on American light water

reactors. Nowadays, Sweden imports its uranium mostly from Canada,

Australia and the former Soviet Union.

- UK – 1981: The UK's uranium production peaked in 1981 and

the supply is running out. Yet the UK still plans to build more nuclear

power plants.

- France – 1988: In France uranium production attained a peak of 3,394 tonnes (7.5×106 lb) in 1988. At the time, this was enough for France to meet the half of its reactor demand from domestic sources. By 1997, production was 1/5 of the 1991 levels. France markedly reduced its market share since 1997. In 2002, France ran out of uranium.

US uranium production peaked in 1960, and again in 1980 (US Energy Information Administration)

- U.S. – 1980: The United States was the world's leading

producer of uranium from 1953 until 1980, when annual US production

peaked at 16,810 tonnes (37×106 lb) (U3O8) according to the OECD redbook. According to the CRB yearbook, US production the peak was at 19,822 tonnes (44×106 lb). The U.S. production hit another maximum in 1996 at 6.3 million pounds (2.9 kt) of uranium oxide (U3O8), then dipped in production for a few years.

Between 2003 and 2007, there has been a 125% increase in production as

demand for uranium has increased. However, as of 2008, production levels

have not come back to 1980 levels.

Uranium mining production in the United States

| Year |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009

|

| U3O8 (Mil lb) |

3.1 |

3.4 |

6.0 |

6.3 |

5.6 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

4.0 |

2.6 |

2.3 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

2.7 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

3.9 |

4.1

|

| U3O8 (tonnes) |

1,410 |

1,540 |

2,700 |

2,860 |

2,540 |

2,130 |

2,090 |

1,800 |

1,180 |

1,040 |

910 |

1,040 |

1,220 |

1,860 |

2,040 |

1,770 |

1,860

|

Uranium mining declined with the last open pit mine

shutting down in 1992 (Shirley Basin, Wyoming). United States

production occurred in the following states (in descending order): New

Mexico, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Texas, Arizona, Florida, Washington,

and South Dakota. The collapse of uranium prices caused all conventional

mining to cease by 1992. "In-situ" recovery or ISR has continued

primarily in Wyoming and adjacent Nebraska as well has recently

restarted in Texas.

- Canada – 1959, 2001?: The first phase of Canadian uranium production peaked at more than 12 kilotonnes (26×106 lb) in 1959.

The 1970s saw renewed interest in exploration and resulted in major

discoveries in northern Saskatchewan's Athabasca Basin. Production

peaked its uranium production a second time at 12,522 tonnes (28×106 lb) in 2001. Experts believe that it will take more than ten years to open new mines.

World peak uranium

Historical opinions of world uranium supply limits

In 1943, Alvin M. Weinberg et al. believed that there were serious limitations on nuclear energy if only U-235 were used as a nuclear power plant fuel. They concluded that breeding was required to usher in the age of nearly endless energy.

In 1956, M. King Hubbert

declared world fissionable reserves adequate for at least the next few

centuries, assuming breeding and reprocessing would be developed into

economical processes.

In 1975 the US Department of the Interior,

Geological Survey, distributed the press release "Known US Uranium

Reserves Won't Meet Demand". It was recommended that the US not depend

on foreign imports of uranium.

Pessimistic predictions

Panel from

All-Atomic Comics (1976) citing pessimistic uranium supply predictions as an argument against nuclear power.

All the following sources predict peak uranium:

- Edward Steidle, Dean of the School of Mineral Industries at Pennsylvania State College, predicted in 1952 that supplies of fissionable elements were too small to support commercial-scale energy production.

- 1980 Robert Vance

while looking back at 40 years of uranium production through all of the

Red Books, found that peak global production was achieved in 1980 at

69,683 tonnes (150×106 lb) from 22 countries. In 2003, uranium production totaled 35,600 tonnes (78×106 lb) from 19 countries.

- 1981 Michael Meacher,

the former environment minister of the UK 1997–2003, and UK Member of

Parliament, reports that peak uranium happened in 1981. He also predicts

a major shortage of uranium sooner than 2013 accompanied with hoarding

and its value pushed up to the levels of precious metals.

- 1989–2015 M. C. Day projected that uranium reserves could run

out as soon as 1989, but, more optimistically, would be exhausted by

2015.

- 2034 Jan Willem Storm van Leeuwen,

an independent analyst with Ceedata Consulting, contends that supplies

of the high-grade uranium ore required to fuel nuclear power generation

will, at current levels of consumption, last to about 2034. Afterwards, the cost of energy to extract the uranium will exceed the price the electric power provided.

- 2035 The Energy Watch Group

has calculated that, even with steep uranium prices, uranium production

will have reached its peak by 2035 and that it will only be possible to

satisfy the fuel demand of nuclear plants until then.

Various agencies have tried to estimate how long these resources will last.

- The European Commission said in 2001 that at the current level

of uranium consumption, known uranium resources would last 42 years.

When added to military and secondary sources, the resources could be

stretched to 72 years. Yet this rate of usage assumes that nuclear power

continues to provide only a fraction of the world's energy supply. If

electric capacity were increased six-fold, then the 72-year supply would

last just 12 years.

- OECD: The world's present measured resources of uranium,

economically recoverable at a price of US$130/kg according to the

industry groups OECD, NEA and IAEA, are enough to last for 100 years at current consumption.

- According to the Australian Uranium Association,

yet another industry group, assuming the world's current rate of

consumption at 66,500 tonnes of uranium per year and the world's present

measured resources of uranium (4.7 Mt) are enough to last for 70 years.

Optimistic predictions

All the following references claim that the supply is far more than demand. Therefore, they do not predict peak uranium.

- In his 1956 landmark paper, M. King Hubbert

wrote "There is promise, however, provided mankind can solve its

international problems and not destroy itself with nuclear weapons, and

provided world population (which is now expanding at such a rate as to

double in less than a century) can somehow be brought under control,

that we may at last have found an energy supply adequate for our needs

for at least the next few centuries of the 'foreseeable future.'" Hubbert's study assumed that breeder reactors would replace light water reactors

and that uranium would be bred into plutonium (and possibly thorium

would be bred into uranium). He also assumed that economic means of

reprocessing would be discovered. For political, economic and nuclear

proliferation reasons, the plutonium economy never materialized. Without it, uranium is used up in a once-through process and will peak and run out much sooner.

However, at present, it is generally found to be cheaper to mine new

uranium out of the ground than to use reprocessed uranium, and therefore

the use of reprocessed uranium is limited to only a few nations.

- The OECD estimates that with the world nuclear electricity

generating rates of 2002, with LWR, once-through fuel cycle, there are

enough conventional resources to last 85 years using known resources and

270 years using known and as yet undiscovered resources. With breeders,

this is extended to 8,500 years.

If one is willing to pay $300/kg for uranium, there is a vast quantity available in the ocean.

It is worth noting that since fuel cost only amounts to a small

fraction of nuclear energy total cost per kWh, and raw uranium price

also constitutes a small fraction of total fuel costs, such an increase

on uranium prices wouldn't involve a very significant increase in the

total cost per kWh produced.

- In 1983, physicist Bernard Cohen proposed that uranium is effectively inexhaustible, and could therefore be considered a renewable source of energy. He claims that fast breeder reactors,

fueled by naturally replenished uranium extracted from seawater, could

supply energy at least as long as the sun's expected remaining lifespan

of five billion years.

While uranium is a finite mineral resource within the earth, the

hydrogen in the sun is finite too – thus, if the resource of nuclear

fuel can last over such time scales, as Cohen contends, then nuclear

energy is every bit as sustainable as solar power or any other source of

energy, in terms of sustainability over the time scale of life

surviving on this planet.

We thus conclude that all the world’s energy requirements for the remaining 5×109

yr of existence of life on Earth could be provided by breeder reactors

without the cost of electricity rising by as much as 1% due to fuel

costs. This is consistent with the definition of a "renewable" energy

source in the sense in which that term is generally used.

His paper assumes extraction of uranium from seawater at the rate of 16 kilotonnes (35×106 lb) per year of uranium. The current demand for uranium is near 70 kilotonnes (150×106 lb)

per year; however, the use of breeder reactors means that uranium would

be used at least 60 times more efficiently than today.

- James Hopf, a nuclear engineer writing for American Energy

Independence in 2004, believes that there is several hundred years'

supply of recoverable uranium even for standard reactors. For breeder

reactors, "it is essentially infinite".

All the following references claim that the supply is far more than

demand. Therefore, they believe that uranium will not deplete in the

foreseeable future.

- The IAEA

estimates that using only known reserves at the current rate of demand

and assuming a once-through nuclear cycle that there is enough uranium

for at least 100 years. However, if all primary known reserves,

secondary reserves, undiscovered and unconventional sources of uranium

are used, uranium will be depleted in 47,000 years.

- Kenneth S. Deffeyes estimates that if one can accept ore one tenth as rich then the supply of available uranium increased 300 times.

His paper shows that uranium concentration in ores is log-normal

distributed. There is relatively little high-grade uranium and a large

supply of very low grade uranium.

- Ernest Moniz, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the former United States Secretary of Energy,

testified in 2009 that an abundance of uranium had put into question

plans to reprocess spent nuclear fuel. The reprocessing plans dated from

decades previous, when uranium was thought to be scarce. But now,

"roughly speaking, we’ve got uranium coming out of our ears, for a long,

long time," Professor Moniz said.

Possible effects and consequences

As

uranium production declines, uranium prices would be expected to

increase. However, the price of uranium makes up only 9% of the cost of

running a nuclear power plant, much lower than the cost of coal in a

coal-fired power plant (77%), or the cost of natural gas in a gas-fired

power plant (93%).

Uranium is different from conventional energy resources, such as

oil and coal, in several key aspects. Those differences limit the

effects of short-term uranium shortages, but most have no bearing on the

eventual depletion. Some key features are:

- The uranium market is diverse, and no country has a monopoly influence on its prices.

- Thanks to the extremely high energy density of uranium, stockpiling of several years' worth of fuel is feasible.

- Significant secondary supplies of already mined uranium exist,

including decommissioned nuclear weapons, depleted uranium tails

suitable for reenrichment, and existing stockpiles.

- Vast amounts of uranium, roughly 800 times the known reserves of

mined uranium, are contained in extremely dilute concentrations in

seawater.

- Introduction of fast neutron reactors, combined with seawater uranium extraction, would make the uranium supply virtually inexhaustible. There are currently seven experimental fast neutron reactors running globally, in India, Japan, Russia and China.

Fast neutron reactors (breeder reactors) could utilize large amounts of Uranium-238 indirectly by conversion to Plutonium-239, rather than fissioning primarily just Uranium-235 (which is 0.7% of original mined uranium), for approximately a factor of 100 increase in uranium usage efficiency.

Intermediate between conventional estimates of reserves and the 40

trillion tons total of uranium in Earth's crust (trace concentrations

adding up over its 3 * 1019 ton mass), there are ores of lower grade than otherwise practical but of still higher concentration than the average rock. Accordingly, resource figures depend on economic and technological assumptions.

Uranium price

Monthly uranium spot price in US$.

The uranium spot price has increased from a low in Jan 2001 of US$6.40 per pound of U3O8 to a peak in June 2007 of US$135. The uranium prices have dropped substantially since. Currently (15 July 2013) the uranium spot is US$38.

The high price in 2007 resulted from shrinking weapons stockpiles and a flood at the Cigar Lake Mine, coupled with expected rises in demand due to more reactors coming online, leading to a uranium price bubble. Miners and Utilities are bitterly divided on uranium prices.

As prices go up, production responds from existing mines, and

production from newer, harder to develop or lower quality uranium ores

begins. Currently, much of the new production is coming from Kazakhstan.

Production expansion is expected in Canada and in the United States.

However, the number of projects waiting in the wings to be brought

online now are far less than there were in the 1970s. There have been

some encouraging signs that production from existing or planned mines is

responding or will respond to higher prices. The supply of uranium has

recently become very inelastic. As the demand increases, the prices

respond dramatically.

As of 2018 the price of nuclear fuel was stable at around

US$38.81 per pound, 81 cents more than in 2013 and 1 cent more than in

2017, way lower than inflation. At such a low and stable price, breeding

is uneconomical.

Number of contracts

Unlike

other metals such as gold, silver, copper or nickel, uranium is not

widely traded on an organized commodity exchange such as the London

Metal Exchange. It is traded on the NYMEX but on very low volume. Instead, it is traded in most cases through contracts negotiated directly between a buyer and a seller.

The structure of uranium supply contracts varies widely. The prices are

either fixed or based on references to economic indices such as GDP,

inflation or currency exchange. Contracts traditionally are based on the

uranium spot price and rules by which the price can escalate. Delivery

quantities, schedules, and prices vary from contract to contract and

often from delivery to delivery within the term of a contract.

Since the number of companies mining uranium is small, the number

of available contracts is also small. Supplies are running short due to

flooding of two of the world's largest mines and a dwindling amount of

uranium salvaged from nuclear warheads being removed from service.

While demand for the metal has been steady for years, the price of

uranium is expected to surge as a host of new nuclear plants come

online.

Mining

Rising uranium prices draw investments into new uranium mining projects.

Mining companies are returning to abandoned uranium mines with new

promises of hundreds of jobs and millions in royalties. Some locals want

them back. Others say the risk is too great, and will try to stop those

companies "until there's a cure for cancer."

Electric utilities

Since

many utilities have extensive stockpiles and can plan many months in

advance, they take a wait-and-see approach on higher uranium costs. In

2007, spot prices rose significantly due to announcements of planned

reactors or new reactors coming online.

Those trying to find uranium in a rising cost climate are forced to

face the reality of a seller's market. Sellers remain reluctant to sell

significant quantities. By waiting longer, sellers expect to get a

higher price for the material they hold. Utilities on the other hand,

are very eager to lock up long-term uranium contracts.

According to the NEA, the nature of nuclear generating costs

allows for significant increases in the costs of uranium before the

costs of generating electricity significantly increase. A 100% increase

in uranium costs would only result in a 5% increase in electric cost.

This is because uranium has to be converted to gas, enriched, converted

back to yellow cake and fabricated into fuel elements. The cost of the

finished fuel assemblies are dominated by the processing costs, not the

cost of the raw materials.

Furthermore, the cost of electricity from a nuclear power plant is

dominated by the high capital and operating costs, not the cost of the

fuel. Nevertheless, any increase in the price of uranium is eventually

passed on to the consumer either directly or through a fuel surcharge. As of 2020, this has not happened and the price of nuclear fuel is low enough to make breeding uneconomical.

Substitutes

An alternative to uranium is thorium

which is three times more common than uranium. Fast breeder reactors

are not needed. Compared to conventional uranium reactors, thorium

reactors using the thorium fuel cycle may produce some 40 times the amount of energy per unit of mass. However, creating the technology, infrastructure and know-how needed for a thorium-fuel economy is uneconomical at current and predicted uranium prices.

If nuclear power prices rise too quickly, or too high, power

companies may look for substitutes in fossil energy (coal, oil, and gas)

and/or renewable energy,

such as hydro, bio-energy, solar thermal electricity, geothermal, wind,

tidal energy. Both fossil energy and some renewable electricity sources

(e.g. hydro, bioenergy, solar thermal electricity and geothermal) can

be used as base-load.