Kafir (Arabic: كافر kāfir; plural كَافِرُونَ kāfirūna, كفّار kuffār or كَفَرَة kafarah; feminine كافرة kāfirah; feminine plural كافرات kāfirāt or كوافر kawāfir) is an Arabic and Islamic term which, in the Islamic tradition, refers to a person who disbelieves in God as per Islam, or denies his authority, or rejects the tenets of Islam. The term is often translated as "infidel", "pagan", "rejector", "denier", "disbeliever", "unbeliever", "nonbeliever", and "non-Muslim". The term is used in different ways in the Quran, with the most fundamental sense being "ungrateful" (toward God). Kufr means "unbelief" or "non-belief", "to be thankless", "to be faithless", or "ingratitude". The opposite term of kufr is īmān (faith), and the opposite of kāfir is muʾmin (believer). A person who denies the existence of a creator might be called a dahri.

Kafir is sometimes used interchangeably with mushrik (مشرك, those who practice polytheism), another type of religious wrongdoer mentioned frequently in the Quran and other Islamic works. (Other, sometimes overlapping Quranic terms for wrong doers are ẓallām (villain, oppressor) and fāsiq (sinner, fornicator).) Historically, while Islamic scholars agreed that a polytheist/mushrik is a kafir, they sometimes disagreed on the propriety of applying the term to Muslims who committed a grave sin or to the People of the Book. The Quran distinguishes between mushrikun and People of the Book, reserving the former term for idol-worshippers, although some classical commentators considered the Christian doctrine to be a form of shirk.

In modern times, kafir is sometimes applied towards self-professed Muslims particularly by members of Islamist movements. The act of declaring another self-professed Muslim a kafir is known as takfir, a practice that has been condemned but also employed in theological and political polemics over the centuries. A Dhimmī or Muʿāhid is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. Dhimmī were exempt from certain duties assigned specifically to Muslims if they paid the poll tax (jizya) but were otherwise equal under the laws of property, contract, and obligation according to some scholars, whereas others state that religious minorities subjected to the status of Dhimmī (such as Christians, Jews, Samaritans, Gnostics, Mandeans, and Zoroastrians) were inferior to the status of Muslims in Islamic states. Jews and Christians were required to pay the jizya and kharaj taxes, while others, depending on the different rulings of the four madhhab, might be required to convert to Islam, pay the jizya, be exiled, or killed under the Islamic death penalty.

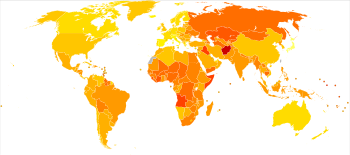

In 2019, Nahdlatul Ulama, the world's largest independent Islamic organization based in Indonesia, issued a proclamation urging Muslims to refrain from using the word "kafir" to refer to non-Muslims, because the term is both offensive and perceived as "theologically violent".

Etymology

The word kāfir is the active participle of the verb كَفَرَ kafara, from root ك-ف-ر K-F-R. As a pre-Islamic term it described farmers burying seeds in the ground. One of its applications in the Quran has also the same meaning as farmer. Since farmers cover the seeds with soil while planting, the word kāfir implies a person who hides or covers. Ideologically, it implies a person who hides or covers the truth. Arabic poets personify the darkness of night as kâfir, perhaps as a survival of pre-Islamic Arabian religious or mythological usage.

The noun for disbelief, "blasphemy", "impiety" rather than the person who disbelieves, is kufr.

Usage

The practice of declaring another Muslim as a kafir is takfir. Kufr (unbelief) and shirk (idolatry) are used throughout the Quran and sometimes used interchangeably by Muslims. According to Salafist scholars, Kufr is the "denial of the Truth" (truth in the form of articles of faith in Islam), and shirk means devoting "acts of worship to anything beside God" or "the worship of idols and other created beings". So a mushrik may worship other things while also "acknowledging God".

In the Quran

The distinction between those who believe in Islam and those who do not is an essential one in the Quran. Kafir, and its plural kuffaar, is used directly 134 times in Quran, its verbal noun "kufr" is used 37 times, and the verbal cognates of kafir are used about 250 times.

By extension of the basic meaning of the root, "to cover", the term is used in the Quran in the senses of ignore/fail to acknowledge and to spurn/be ungrateful. The meaning of "disbelief", which has come to be regarded as primary, retains all of these connotations in the Quranic usage. In the Quranic discourse, the term typifies all things that are unacceptable and offensive to God. Whereby it is not necessary to deny the existence of God, but it suffices to deviate from his will as seen in a dialogue between God and Iblis, the latter called a kafir. According to Al-Damiri (1341–1405) it is neither denying God, nor the act of disobedience alone, but Iblis' attitude (claiming that God's command is unjust), which makes him a kafir. The most fundamental sense of kufr in the Quran is "ingratitude", the willful refusal to acknowledge or appreciate the benefits that God bestows on humankind, including clear signs and revealed scriptures.

According to the E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 4, the term first applied in the Quran to unbelieving Meccans, who endeavoured "to refute and revile the Prophet". A waiting attitude towards the kafir was recommended at first for Muslims; later, Muslims were ordered to keep apart from unbelievers and defend themselves against their attacks and even take the offensive. Most passages in the Quran referring to unbelievers in general talk about their fate on the day of judgement and destination in hell.

According to scholar Marilyn Waldman, as the Quran "progresses" (as the reader goes from the verses revealed first to later ones), the meaning behind the term kafir does not change but "progresses", i.e. "accumulates meaning over time". As the Islamic prophet Muhammad's views of his opponents change, his use of kafir "undergoes a development". Kafir moves from being one description of Muhammad's opponents to the primary one. Later in the Quran, kafir becomes more and more connected with shirk. Finally, towards the end of the Quran, kafir begins to also signify the group of people to be fought by the mu'minīn (believers).

Types of unbelievers

People of the Book

The status of the Ahl al-Kitab (People of the Book), particularly Jews and Christians, with respect to the Islamic notions of unbelief is disputed.

Charles Adams writes that the Quran reproaches the People of the Book with kufr for rejecting Muhammad's message when they should have been the first to accept it as possessors of earlier revelations, and singles out Christians for disregarding the evidence of God's unity. The Quranic verse 5:73 ("Certainly they disbelieve [kafara] who say: God is the third of three"), among other verses, has been traditionally understood in Islam as rejection of the Christian doctrine on the Trinity, though modern scholarship has suggested alternative interpretations. Other Quranic verses strongly deny the deity of Jesus Christ, son of Mary and reproach the people who treat Jesus as equal with God as disbelievers who will have strayed from the path of God which would result in the entrance of hellfire. While the Quran does not recognize the attribute of Jesus as the Son of God or God himself, it respects Jesus as a prophet and messenger of God sent to children of Israel. Some Muslim thinkers such as Mohamed Talbi have viewed the most extreme Quranic presentations of the dogmas of the Trinity and divinity of Jesus ( 5:19, 5:75–76, 5:119) as non-Christian formulas that were rejected by the Church.

On the other hand, modern scholarship has suggested alternative interpretations of verse Q. 5:73. Cyril Glasse criticizes the use of kafirun [pl. of kafir] to describe Christians as "loose usage". According to the Encyclopedia of Islam, in traditional Islamic jurisprudence, ahl al-kitab are "usually regarded more leniently than other kuffar [pl. of kafir]" and "in theory" a Muslim commits a punishable offense if he says to a Jew or a Christian: "Thou unbeliever". (Charles Adams and A. Kevin Reinhart also write that "later thinkers" in Islam distinguished between ahl al-kitab and the polytheists/mushrikīn).

Historically, People of the Book permanently residing under Islamic rule were entitled to a special status known as dhimmī, while those visiting Muslim lands received a different status known as musta'min.

Mushrikun

Mushrikun (pl. of mushrik) are those who practice shirk, which literally means "association" and refers to accepting other gods and divinities alongside the god of the Muslims – Allah (as God's "associates"). The term is often translated as polytheism. The Quran distinguishes between mushrikun and People of the Book, reserving the former term for idol worshipers, although some classical commentators considered Christian doctrine to be a form of shirk. Shirk is held to be the worst form of disbelief, and it is identified in the Quran as the only sin that God will not pardon ( 4:48, 4:116).

Accusations of shirk have been common in religious polemics within Islam. Thus, in the early Islamic debates on free will and theodicy, Sunni theologians charged their Mu'tazila adversaries with shirk, accusing them of attributing to man creative powers comparable to those of God in both originating and executing his own actions. Mu'tazila theologians, in turn, charged the Sunnis with shirk on the grounds that under their doctrine a voluntary human act would result from an "association" between God, who creates the act, and the individual who appropriates it by carrying it out.

In classical jurisprudence, Islamic religious tolerance applied only to the People of the Book, while mushrikun, based on the Sword Verse, faced a choice between conversion to Islam and fight to the death, which may be substituted by enslavement. In practice, the designation of People of the Book and the dhimmī status was extended even to non-monotheistic religions of conquered peoples, such as Hinduism. Following destruction of major Hindu temples during the Muslim conquests in South Asia, Hindus and Muslims on the subcontinent came to share a number of popular religious practices and beliefs, such as veneration of Sufi saints and worship at Sufi dargahs, although Hindus may worship at Hindu shrines also.

In the 18th century, followers of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (aka Wahhabis) believed "kufr or shirk" was found in the Muslim community itself, especially in "the practice of popular religion":

shirk took many forms: the attribution to prophets, saints, astrologers, and soothsayers of knowledge of the unseen world, which only God possesses and can grant; the attribution of power to any being except God, including the power of intercession; reverence given in any way to any created thing, even to the tomb of the Prophet; such superstitious customs as belief in omens and in auspicious and inauspicious days; and swearing by the names of the Prophet, ʿAlī, the Shīʿī imams, or the saints. Thus the Wahhābīs acted even to destroy the cemetery where many of the Prophet's most notable companions were buried, on the grounds that it was a center of idolatry.

While ibn Abd al-Wahhab and Wahhābīs was/were "the best-known premodern" revivalist and "sectarian movement" of that era, other revivalists included Shah Ismail Dehlvi and Ahmed Raza Khan Barelvi, leaders of the Mujāhidīn movement on the North-West frontier of India in the early nineteenth century.

Sinners

Whether a Muslim could commit a sin great enough to become a kafir was disputed by jurists in the early centuries of Islam. The most tolerant view (that of the Murji'ah) was that even those who had committed a major sin (kabira) were still believers and "their fate was left to God". The most strict view (that of Kharidji Ibadis, descended from the Kharijites) was that every Muslim who dies having not repented of his sins was considered a kafir. In between these two positions, the Mu'tazila believed that there was a status between believer and unbeliever called "rejected" or fasiq.

Takfir

The Kharijites view that the self-proclaimed Muslim who had sinned and "failed to repent had ipso facto excluded himself from the community, and was hence a kafir" (a practice known as takfir) was considered so extreme by the Sunni majority that they in turn declared the Kharijites to be kuffar, following the hadith that declared, "If a Muslim charges a fellow Muslim with kufr, he is himself a kafir if the accusation should prove untrue".

Nevertheless, in Islamic theological polemics kafir was "a frequent term for the Muslim protagonist" holding the opposite view, according to Brill's Islamic Encyclopedia.

Present-day Muslims who make interpretations that differ from what others believe are declared kafirs; fatwas (edicts by Islamic religious leaders) are issued ordering Muslims to kill them, and some such people have been killed also.

Murtad

Another group that are "distinguished from the mass of kafirun" are the murtad, or apostate ex-Muslims, who are considered renegades and traitors. Their traditional punishment is death, even, according to some scholars, if they recant their abandonment of Islam.

Muʿāhid / Dhimmī

Dhimmī are non-Muslims living under the protection of an Islamic state. Dhimmī were exempt from certain duties assigned specifically to Muslims if they paid the poll tax (jizya) but were otherwise equal under the laws of property, contract, and obligation according to some scholars, whereas others state that religious minorities subjected to the status of Dhimmī (such as Jews, Samaritans, Gnostics, Mandeans, and Zoroastrians) were inferior to the status of Muslims in Islamic states. Jews and Christians were required to pay the jizyah while pagans, depending on the different rulings of the four madhhab, might be required to accept Islam, pay the jizya, be exiled, or be killed under the Islamic death penalty. Some historians believe that forced conversion was rare in Islamic history, and most conversions to Islam were voluntary. Muslim rulers were often more interested in conquest than conversion.

Upon payment of the tax (jizya), the dhimmī would receive a receipt of payment, either in the form of a piece of paper or parchment or as a seal humiliatingly placed upon their neck, and was thereafter compelled to carry this receipt wherever he went within the realms of Islam. Failure to produce an up-to-date jizya receipt on the request of a Muslim could result in death or forced conversion to Islam of the dhimmī in question.

Types of disbelief

Various types of unbelief recognized by legal scholars include:

- kufr bi-l-qawl (verbally expressed unbelief)

- kufr bi-l-fi'l (unbelief expressed through action)

- kufr bi-l-i'tiqad (unbelief of convictions)

- kufr akbar (major unbelief)

- kufr asghar (minor unbelief)

- takfir 'amm (general charge of unbelief, i.e. charged against a community like ahmadiyya

- takfir al-mu'ayyan (charge of unbelief against a particular individual)

- takfir al-'awamm (charge of unbelief against "rank and file Muslims" for example following taqlid.

- takfir al-mutlaq (category covers general statements such as 'whoever says X or does Y is guilty of unbelief')

- kufr asli (original unbelief of non-Muslims, those born to non-Muslim family)

- kufr tari (acquired unbelief of formerly observant Muslims, i.e. apostates)

- Iman

Muslim belief/doctrine is often summarized in "the Six Articles of Faith", (the first five are mentioned together in the Quran 2:285).

- God

- His angels

- His Messengers

- His Revealed Books,

- The Day of Resurrection

- Al-Qadar, Divine Preordainments, i.e. whatever God has ordained must come to pass

According to the Salafi scholar Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al-Hilali, "kufr is basically disbelief in any of the articles of faith. He also lists several different types of major disbelief, (disbelief so severe it excludes those who practice it completely from the fold of Islam):

- Kufr-at-Takdhib: disbelief in divine truth or the denial of any of the articles of Faith (quran 39:32)

- Kufr-al-iba wat-takabbur ma'at-Tasdiq: refusing to submit to God's Commandments after conviction of their truth (quran 2:34)

- Kufr-ash-Shakk waz-Zann: doubting or lacking conviction in the six articles of Faith. (quran 18:35–38)

- Kufr-al-I'raadh: turning away from the truth knowingly or deviating from the obvious signs which God has revealed. (quran 46:3)

- Kufr-an-Nifaaq: hypocritical disbelief (quran 63:2–3)

Minor disbelief or Kufran-Ni'mah indicates "ungratefulness of God's Blessings or Favours".

According to another source, a paraphrase of the Tafsir by Ibn Kathir, there are eight kinds of Al-Kufr al-Akbar (major unbelief), some are the same as those described by Al-Hilali (Kufr-al-I'rad, Kufr-an-Nifaaq) and some different.

- Kufrul-'Inaad: Disbelief out of stubbornness. This applies to someone who knows the Truth and admits to knowing the Truth, and knowing it with his tongue, but refuses to accept it and refrains from making a declaration. God says: Throw into Hell every stubborn disbeliever.

- Kufrul-Inkaar: Disbelief out of denial. This applies to someone who denies with both heart and tongue. God says: They recognize the favors of God, yet they deny them. Most of them are disbelievers.

- Kufrul-Juhood: Disbelief out of rejection. This applies to someone who acknowledges the truth in his heart, but rejects it with his tongue. This type of kufr is applicable to those who call themselves Muslims but who reject any necessary and accepted norms of Islam such as Salah and Zakat. God says: They denied them (our signs) even though their hearts believed in them, out of spite and arrogance.

- Kufrul-Nifaaq: Disbelief out of hypocrisy. This applies to someone who pretends to be a believer but conceals his disbelief. Such a person is called a munafiq or hypocrite. God says: Verily the hypocrites will be in the lowest depths of Hell. You will find no one to help them.

- Kufrul-Kurh: Disbelief out of detesting any of God's commands. God says: Perdition (destruction) has been consigned to those who disbelieve and He will render their actions void. This is because they are averse to that which God has revealed so He has made their actions fruitless.

- Kufrul-Istihzaha: Disbelief due to mockery and derision. God says: Say: Was it at God, His signs and His apostles that you were mocking? Make no excuses. You have disbelieved after you have believed.

- Kufrul-I'raadh: Disbelief due to avoidance. This applies to those who turn away and avoid the truth. God says: And who is more unjust than he who is reminded of his Lord's signs but then turns away from them. Then he forgets what he has sent forward (for the Day of Judgement).

- Kufrul-Istibdaal: Disbelief because of trying to substitute God's Laws with man-made laws. God says: Or have they partners with God who have instituted for them a religion that God has not allowed. God says: Say not concerning that which your tongues put forth falsely (that) is lawful and this is forbidden so as to invent a lie against God. Verily, those who invent a lie against God will never prosper.

Ignorance

In Islam, jahiliyyah ("ignorance") refers to the time of Arabia before Islam.

History of the usage of the term

Usage in the proper sense

When the Islamic empire expanded, the word "kafir" was broadly used as a descriptive term for all pagans and anyone else who disbelieved in Islam. Historically, the attitude toward unbelievers in Islam was determined more by socio-political conditions than by religious doctrine. A tolerance toward unbelievers "impossible to imagine in contemporary Christendom" prevailed even to the time of the Crusades, particularly with respect to the People of the Book. However, due to animosity towards Franks, the term kafir developed into a term of abuse. During the Mahdist War, the Mahdist State used the term kuffar against Ottoman Turks, and the Turks themselves used the term kuffar towards Persians during the Ottoman-Safavid wars. In modern Muslim popular imagination, the dajjal (antichrist-like figure) will have k-f-r written on his forehead.

However, there was extensive religious violence in India between Muslims and non-Muslims during the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire (before the political decline of Islam). In their memoirs on Muslim invasions, enslavement and plunder of this period, many Muslim historians in South Asia used the term Kafir for Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains. Raziuddin Aquil states that "non-Muslims were often condemned as kafirs, in medieval Indian Islamic literature, including court chronicles, Sufi texts and literary compositions" and fatwas were issued that justified persecution of the non-Muslims.

Relations between Jews and Muslims in the Arab world and use of the word "kafir" were equally as complex, and over the last century, issues regarding "kafir" have arisen over the conflict in Israel and Palestine. Calling the Jews of Israel, "the usurping kafir", Yasser Arafat turned on the Muslim resistance and "allegedly set a precedent for preventing Muslims from mobilizing against 'aggressor disbelievers' in other Muslim lands, and enabled 'the cowardly, alien kafir' to achieve new levels of intervention in Muslim affairs."

In 2019, Nahdlatul Ulama, the largest independent Islamic organization in the world based in Indonesia, issued a proclamation urging Muslims to refrain from using the word kafir to refer to non-Muslims, as the term is both offensive and perceived to be "theologically violent".

Muhammad's parents

A hadith in which Muhammad states that his father, Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib, was in Hell, has become a source of disagreement among Islamic scholars about the status of Muhammad's parents. Over the centuries, Sunni scholars have dismissed this hadith despite its appearance in the authoritative Sahih Muslim collection. It passed through a single chain of transmission for three generations, so that its authenticity was not considered certain enough to supersede a theological consensus which stated that people who died before a prophetic message reached them—as Muhammad's father had done—could not be held accountable for not embracing it. Shia Muslim scholars likewise consider Muhammad's parents to be in Paradise. In contrast, the Salafi website IslamQA.info, founded by the Saudi Arabian Salafi scholar Muhammad Al-Munajjid, argues that Islamic tradition teaches that Muhammad's parents were kuffār ("disbelievers") who are in Hell.

Other uses

By the 15th century, Muslims in Africa were using the word Kaffir in reference to the non-Muslim African natives. Many of those kufari were enslaved and sold to European and Asian merchants by their Muslim captors, most of the merchants were from Portugal, which had established trading outposts along the coast of West Africa by that time. These European traders adopted the Arabic word and its derivatives.

Some of the earliest records of European usage of the word can be found in The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589) by Richard Hakluyt. In volume 4, Hakluyt writes: "calling them Cafars and Gawars, which is, infidels or disbelievers". Volume 9 refers to the slaves (slaves called Cafari) and inhabitants of Ethiopia (and they use to go in small shippes, and trade with the Cafars) by two different but similar names. The word is also used in reference to the coast of Africa as land of Cafraria. The 16th century explorer Leo Africanus described the Cafri as "negroes", and he also stated that they constituted one of five principal population groups in Africa. He identified their geographical heartland as being located in a remote region of southern Africa, an area which he designated as Cafraria.

By the late 19th century, the word was in use in English-language newspapers and books. One of the Union-Castle Line ships operating off the South African coast was named SS Kafir.[96] In the early twentieth century, in his book The Essential Kafir, Dudley Kidd writes that the word kafir had come to be used for all dark-skinned South African tribes. Thus, in many parts of South Africa, kafir became synonymous with the word "native". Currently in South Africa, however, the word kaffir is regarded as a racial slur, applied pejoratively or offensively to blacks.

The song "Kafir" by the American technical death metal band Nile on its sixth album Those Whom the Gods Detest uses the violent attitudes that Muslim extremists have towards kafirs as subject matter.

The Nuristani people were formerly known as the Kaffirs of Kafiristan before the Afghan Islamization of the region.

The Kalash people who live in the Hindu Kush mountain range which is located south west of Chitral are referred to as kafirs by the Muslim population of Chitral.

In modern Spanish, the word cafre, derived from the Arabic word kafir by way of the Portuguese language, also means "uncouth" or "savage".