From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as Ga, for gigaannum) and evidence suggests that life emerged prior to 3.7 Ga. Although there is some evidence of life as early as 4.1 to 4.28 Ga, it remains controversial due to the possible non-biological formation of the purported fossils.

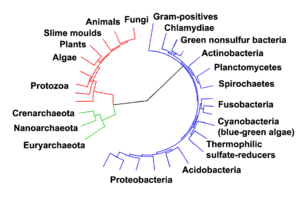

The similarities among all known present-day species indicate that they have diverged through the process of evolution from a common ancestor. Only a very small percentage of species have been identified: one estimate claims that Earth may have 1 trillion species. However, only 1.75–1.8 million have been named and 1.8 million documented in a central database. These currently living species represent less than one percent of all species that have ever lived on Earth.

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The earliest evidence of life comes from biogenic carbon signatures and stromatolite fossils discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks from western Greenland. In 2015, possible "remains of biotic life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia. In March 2017, putative evidence of possibly the oldest forms of life on Earth was reported in the form of fossilized microorganisms discovered in hydrothermal vent precipitates in the Nuvvuagittuq Belt of Quebec, Canada, that may have lived as early as 4.28 billion years ago, not long after the oceans formed 4.4 billion years ago, and not long after the formation of the Earth 4.54 billion years ago.

Microbial mats of coexisting bacteria and archaea were the dominant form of life in the early Archean Epoch and many of the major steps in early evolution are thought to have taken place in this environment. The evolution of photosynthesis, around 3.5 Ga, eventually led to a buildup of its waste product, oxygen, in the atmosphere, leading to the great oxygenation event, beginning around 2.4 Ga. The earliest evidence of eukaryotes (complex cells with organelles) dates from 1.85 Ga, and while they may have been present earlier, their diversification accelerated when they started using oxygen in their metabolism. Later, around 1.7 Ga, multicellular organisms began to appear, with differentiated cells performing specialised functions. Sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of male and female reproductive cells (gametes) to create a zygote in a process called fertilization is, in contrast to asexual reproduction, the primary method of reproduction for the vast majority of macroscopic organisms, including almost all eukaryotes (which includes animals and plants). However the origin and evolution of sexual reproduction remain a puzzle for biologists though it did evolve from a common ancestor that was a single celled eukaryotic species. Bilateria, animals having a left and a right side that are mirror images of each other, appeared by 555 Ma (million years ago).

Algae-like multicellular land plants are dated back even to about 1 billion years ago, although evidence suggests that microorganisms formed the earliest terrestrial ecosystems, at least 2.7 Ga. Microorganisms are thought to have paved the way for the inception of land plants in the Ordovician period. Land plants were so successful that they are thought to have contributed to the Late Devonian extinction event. (The long causal chain implied seems to involve (1) the success of early tree archaeopteris drew down CO2 levels, leading to global cooling and lowered sea levels, (2) roots of archeopteris fostered soil development which increased rock weathering, and the subsequent nutrient run-off may have triggered algal blooms resulting in anoxic events which caused marine-life die-offs. Marine species were the primary victims of the Late Devonian extinction.)

Ediacara biota appear during the Ediacaran period, while vertebrates, along with most other modern phyla originated about 525 Ma during the Cambrian explosion. During the Permian period, synapsids, including the ancestors of mammals, dominated the land, but most of this group became extinct in the Permian–Triassic extinction event 252 Ma. During the recovery from this catastrophe, archosaurs became the most abundant land vertebrates;

one archosaur group, the dinosaurs, dominated the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. After the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 Ma killed off the non-avian dinosaurs, mammals increased rapidly in size and diversity. Such mass extinctions may have accelerated evolution by providing opportunities for new groups of organisms to diversify.

Earliest history of Earth

Main article: History of Earth

Oldest meteorite fragments found on Earth are about 4.54 billion years old; this, coupled primarily with the dating of ancient lead deposits, has put the estimated age of Earth at around that time. The Moon has the same composition as Earth's crust but does not contain an iron-rich core like the Earth's. Many scientists think that about 40 million years after the formation of Earth, it collided with a body the size of Mars, throwing crust material into the orbit that formed the Moon. Another hypothesis is that the Earth and Moon started to coalesce at the same time but the Earth, having much stronger gravity than the early Moon, attracted almost all the iron particles in the area.

Until 2001, the oldest rocks found on Earth were about 3.8 billion years old, leading scientists to estimate that the Earth's surface had been molten until then. Accordingly, they named this part of Earth's history the Hadean. However, analysis of zircons formed 4.4 Ga indicates that Earth's crust solidified about 100 million years after the planet's formation and that the planet quickly acquired oceans and an atmosphere, which may have been capable of supporting life.

Evidence from the Moon indicates that from 4 to 3.8 Ga it suffered a Late Heavy Bombardment by debris that was left over from the formation of the Solar System, and the Earth should have experienced an even heavier bombardment due to its stronger gravity. While there is no direct evidence of conditions on Earth 4 to 3.8 Ga, there is no reason to think that the Earth was not also affected by this late heavy bombardment. This event may well have stripped away any previous atmosphere and oceans; in this case gases and water from comet impacts may have contributed to their replacement, although outgassing from volcanoes on Earth would have supplied at least half. However, if subsurface microbial life had evolved by this point, it would have survived the bombardment.

Earliest evidence for life on Earth

The earliest identified organisms were minute and relatively featureless, and their fossils look like small rods that are very difficult to tell apart from structures that arise through abiotic physical processes. The oldest undisputed evidence of life on Earth, interpreted as fossilized bacteria, dates to 3 Ga. Other finds in rocks dated to about 3.5 Ga have been interpreted as bacteria, with geochemical evidence also seeming to show the presence of life 3.8 Ga. However, these analyses were closely scrutinized, and non-biological processes were found which could produce all of the "signatures of life" that had been reported. While this does not prove that the structures found had a non-biological origin, they cannot be taken as clear evidence for the presence of life. Geochemical signatures from rocks deposited 3.4 Ga have been interpreted as evidence for life, although these statements have not been thoroughly examined by critics.

Evidence for fossilized microorganisms considered to be 3.77 billion to 4.28 billion years old was found in the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt in Quebec, Canada, although the evidence is disputed as inconclusive.

Origins of life on Earth

Biologists reason that all living organisms on Earth must share a single last universal ancestor, because it would be virtually impossible that two or more separate lineages could have independently developed the many complex biochemical mechanisms common to all living organisms.

Independent emergence on Earth

Life on Earth is based on carbon and water. Carbon provides stable frameworks for complex chemicals and can be easily extracted from the environment, especially from carbon dioxide. There is no other chemical element whose properties are similar enough to carbon's to be called an analogue; silicon, the element directly below carbon on the periodic table, does not form very many complex stable molecules, and because most of its compounds are water-insoluble and because silicon dioxide is a hard and abrasive solid in contrast to carbon dioxide at temperatures associated with living things, it would be more difficult for organisms to extract. The elements boron and phosphorus have more complex chemistries, but suffer from other limitations relative to carbon. Water is an excellent solvent and has two other useful properties: the fact that ice floats enables aquatic organisms to survive beneath it in winter; and its molecules have electrically negative and positive ends, which enables it to form a wider range of compounds than other solvents can. Other good solvents, such as ammonia, are liquid only at such low temperatures that chemical reactions may be too slow to sustain life, and lack water's other advantages. Organisms based on alternative biochemistry may, however, be possible on other planets.

Research on how life might have emerged from non-living chemicals focuses on three possible starting points: self-replication, an organism's ability to produce offspring that are very similar to itself; metabolism, its ability to feed and repair itself; and external cell membranes, which allow food to enter and waste products to leave, but exclude unwanted substances. Research on abiogenesis still has a long way to go, since theoretical and empirical approaches are only beginning to make contact with each other.

Replication first: RNA world

Even the simplest members of the three modern domains of life use DNA to record their "recipes" and a complex array of RNA and protein molecules to "read" these instructions and use them for growth, maintenance and self-replication. The discovery that some RNA molecules can catalyze both their own replication and the construction of proteins led to the hypothesis of earlier life-forms based entirely on RNA. These ribozymes could have formed an RNA world in which there were individuals but no species, as mutations and horizontal gene transfers would have meant that offspring were likely to have different genomes from their parents, and evolution occurred at the level of genes rather than organisms. RNA would later have been replaced by DNA, which can build longer, more stable genomes, strengthening heritability and expanding the capabilities of individual organisms. Ribozymes remain as the main components of ribosomes, the "protein factories" in modern cells. Evidence suggests the first RNA molecules formed on Earth prior to 4.17 Ga.

Although short self-replicating RNA molecules have been artificially produced in laboratories, doubts have been raised about whether natural non-biological synthesis of RNA is possible. The earliest "ribozymes" may have been formed of simpler nucleic acids such as PNA, TNA or GNA, which would have been replaced later by RNA.

In 2003, it was proposed that porous metal sulfide precipitates would assist RNA synthesis at about 100 °C (212 °F) and ocean-bottom pressures near hydrothermal vents. Under this hypothesis, lipid membranes would be the last major cell components to appear and, until then, the protocells would be confined to the pores.

Metabolism first: Iron–sulfur world

A series of experiments starting in 1997 showed that early stages in the formation of proteins from inorganic materials including carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide could be achieved by using iron sulfide and nickel sulfide as catalysts. Most of the steps required temperatures of about 100 °C (212 °F) and moderate pressures, although one stage required 250 °C (482 °F) and a pressure equivalent to that found under 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) of rock. Hence it was suggested that self-sustaining synthesis of proteins could have occurred near hydrothermal vents.

Membranes first: Lipid world

It has been suggested that double-walled "bubbles" of lipids like those that form the external membranes of cells may have been an essential first step. Experiments that simulated the conditions of the early Earth have reported the formation of lipids, and these can spontaneously form liposomes, double-walled "bubbles," and then reproduce themselves. Although they are not intrinsically information-carriers as nucleic acids are, they would be subject to natural selection for longevity and reproduction. Nucleic acids such as RNA might then have formed more easily within the liposomes than outside.

The clay hypothesis

RNA is complex and there are doubts about whether it can be produced non-biologically in the wild. Some clays, notably montmorillonite, have properties that make them plausible accelerators for the emergence of an RNA world: they grow by self-replication of their crystalline pattern; they are subject to an analogue of natural selection, as the clay "species" that grows fastest in a particular environment rapidly becomes dominant; and they can catalyze the formation of RNA molecules. Although this idea has not become the scientific consensus, it still has active supporters.

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of fatty acids into "bubbles," and that the "bubbles" could encapsulate RNA attached to the clay. These "bubbles" can then grow by absorbing additional lipids and then divide. The formation of the earliest cells may have been aided by similar processes.

A similar hypothesis presents self-replicating iron-rich clays as the progenitors of nucleotides, lipids and amino acids.

Prebiotic environments

Geothermal springs

Wet-dry cycles at geothermal springs are shown to solve the problem of hydrolysis and promote the polymerization and vesicle encapsulation of biopolymers. The temperatures of geothermal springs are suitable for biomolecules. Silica minerals and metal sulfides at these environments have photocatalytic properties to catalyze biomolecules. Solar UV exposure also promotes the synthesis of biomolecules like RNA nucleotides. An analysis of hydrothermal veins at a 3.5 Gya geothermal spring setting were found to have elements required for the origin of life, which are potassium, boron, hydrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, zinc, nitrogen, and oxygen. Mulkidjanian and colleagues find that such environments have identical ionic concentrations to the cytoplasm of modern cells. Fatty acids in acidic or slightly alkaline geothermal springs assemble into vesicles after wet-dry cycles as there is a lower concentration of ionic solutes at geothermal springs since they are freshwater environments, in contrast to seawater which has a higher concentration of ionic solutes. For organic compounds to be present at geothermal springs, they would have likely been transported by carbonaceous meteors. The molecules that fell from the meteors were then accumulated in geothermal springs. As for the evolutionary implications, freshwater heterotrophic cells that depended upon synthesized organic compounds later evolved photosynthesis because of the continuous exposure to sunlight as well as their cell walls with ion pumps to maintain their intracellular metabolism after they entered the oceans.

Deep sea hydrothermal vents

Catalytic mineral particles at these environments likely catalyzed organic compounds. Scientists simulated laboratory conditions that were identical to white smokers and successfully oligomerized RNA, measured to be 4 units long. Another experiment that replicated conditions also similar white smokers, with phospholipids present resulted in the assembly of vesicles. Exergonic reactions at hydrothermal vents are suggested to have been a source of free energy that promoted chemical reactions, synthesis of organic molecules, and are inducive to chemical gradients. In small rock pore systems, membranous structures between alkaline seawater and the acidic ocean would be conducive to proton gradients. Small mineral cavities or mineral gels could have been a compartment for abiogenic processes. A genomic analysis supports this hypothesis as they found 355 genes that likely traced to LUCA upon 6.1 million sequenced prokaryotic genes. They reconstruct LUCA as a thermophilic anaerobe with a Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, implying an origin of life at white smokers.

Life "seeded" from elsewhere

The Panspermia hypothesis does not explain how life arose originally, but simply examines the possibility of it coming from somewhere other than Earth. The idea that life on Earth was "seeded" from elsewhere in the Universe dates back at least to the Greek philosopher Anaximander in the sixth century BCE. In the twentieth century it was proposed by the physical chemist Svante Arrhenius, by the astronomers Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe, and by molecular biologist Francis Crick and chemist Leslie Orgel.

There are three main versions of the "seeded from elsewhere" hypothesis: from elsewhere in our Solar System via fragments knocked into space by a large meteor impact, in which case the most credible sources are Mars and Venus; by alien visitors, possibly as a result of accidental contamination by microorganisms that they brought with them; and from outside the Solar System but by natural means.

Experiments in low Earth orbit, such as EXOSTACK, have demonstrated that some microorganism spores can survive the shock of being catapulted into space and some can survive exposure to outer space radiation for at least 5.7 years. Scientists are divided over the likelihood of life arising independently on Mars, or on other planets in our galaxy.

Environmental and evolutionary impact of microbial mats

Microbial mats are multi-layered, multi-species colonies of bacteria and other organisms that are generally only a few millimeters thick, but still contain a wide range of chemical environments, each of which favors a different set of microorganisms. To some extent each mat forms its own food chain, as the by-products of each group of microorganisms generally serve as "food" for adjacent groups.

Stromatolites are stubby pillars built as microorganisms in mats slowly migrate upwards to avoid being smothered by sediment deposited on them by water. There has been vigorous debate about the validity of alleged stromatolite fossils from before 3 Ga, with critics arguing that they could have been formed by non-biological processes. In 2006, another find of stromatolites was reported from the same part of Australia, in rocks dated to 3.5 Ga.

In modern underwater mats the top layer often consists of photosynthesizing cyanobacteria which create an oxygen-rich environment, while the bottom layer is oxygen-free and often dominated by hydrogen sulfide emitted by the organisms living there. Oxygen is toxic to organisms that are not adapted to it, but greatly increases the metabolic efficiency of oxygen-adapted organisms; oxygenic photosynthesis by bacteria in mats increased biological productivity by a factor of between 100 and 1,000. The source of hydrogen atoms used by oxygenic photosynthesis is water, which is much more plentiful than the geologically produced reducing agents required by the earlier non-oxygenic photosynthesis. From this point onwards life itself produced significantly more of the resources it needed than did geochemical processes.

Oxygen became a significant component of Earth's atmosphere about 2.4 Ga. Although eukaryotes may have been present much earlier, the oxygenation of the atmosphere was a prerequisite for the evolution of the most complex eukaryotic cells, from which all multicellular organisms are built. The boundary between oxygen-rich and oxygen-free layers in microbial mats would have moved upwards when photosynthesis shut down overnight, and then downwards as it resumed on the next day. This would have created selection pressure for organisms in this intermediate zone to acquire the ability to tolerate and then to use oxygen, possibly via endosymbiosis, where one organism lives inside another and both of them benefit from their association.

Cyanobacteria have the most complete biochemical "toolkits" of all the mat-forming organisms. Hence they are the most self-sufficient, well-adapted to strike out on their own both as floating mats and as the first of the phytoplankton, providing the basis of most marine food chains.

Diversification of eukaryotes

Chromatin, nucleus, endomembrane system, and mitochondria

Eukaryotes may have been present long before the oxygenation of the atmosphere, but most modern eukaryotes require oxygen, which is used by their mitochondria to fuel the production of ATP, the internal energy supply of all known cells. In the 1970s, a vigorous debate concluded that eukaryotes emerged as a result of a sequence of endosymbiosis between prokaryotes. For example: a predatory microorganism invaded a large prokaryote, probably an archaean, but instead of killing its prey, the attacker took up residence and evolved into mitochondria; one of these chimeras later tried to swallow a photosynthesizing cyanobacterium, but the victim survived inside the attacker and the new combination became the ancestor of plants; and so on. After each endosymbiosis, the partners eventually eliminated unproductive duplication of genetic functions by re-arranging their genomes, a process which sometimes involved transfer of genes between them. Another hypothesis proposes that mitochondria were originally sulfur- or hydrogen-metabolising endosymbionts, and became oxygen-consumers later. On the other hand, mitochondria might have been part of eukaryotes' original equipment.

There is a debate about when eukaryotes first appeared: the presence of steranes in Australian shales may indicate eukaryotes at 2.7 Ga; however, an analysis in 2008 concluded that these chemicals infiltrated the rocks less than 2.2 Ga and prove nothing about the origins of eukaryotes. Fossils of the algae Grypania have been reported in 1.85 billion-year-old rocks (originally dated to 2.1 Ga but later revised), indicating that eukaryotes with organelles had already evolved. A diverse collection of fossil algae were found in rocks dated between 1.5 and 1.4 Ga. The earliest known fossils of fungi date from 1.43 Ga.

Plastids

Plastids, the superclass of organelles of which chloroplasts are the best-known exemplar, are thought to have originated from endosymbiotic cyanobacteria. The symbiosis evolved around 1.5 Ga and enabled eukaryotes to carry out oxygenic photosynthesis. Three evolutionary lineages of photosynthetic plastids have since emerged: chloroplasts in green algae and plants, rhodoplasts in red algae and cyanelles in the glaucophytes. Not long after this primary endosymbiosis of plastids, rhodoplasts and chloroplasts were passed down to other bikonts, establishing an eukaryotic assemblage of phytoplankton by the end of the Neoproterozoic Eon.

Sexual reproduction and multicellular organisms

Evolution of sexual reproduction

The defining characteristics of sexual reproduction in eukaryotes are meiosis and fertilization, resulting in genetic recombination, giving offspring 50% of their genes from each parent. By contrast, in asexual reproduction there is no recombination, but occasional horizontal gene transfer. Bacteria also exchange DNA by bacterial conjugation, enabling the spread of resistance to antibiotics and other toxins, and the ability to utilize new metabolites. However, conjugation is not a means of reproduction, and is not limited to members of the same species – there are cases where bacteria transfer DNA to plants and animals.

On the other hand, bacterial transformation is clearly an adaptation for transfer of DNA between bacteria of the same species. This is a complex process involving the products of numerous bacterial genes and can be regarded as a bacterial form of sex. This process occurs naturally in at least 67 prokaryotic species (in seven different phyla). Sexual reproduction in eukaryotes may have evolved from bacterial transformation.

The disadvantages of sexual reproduction are well-known: the genetic reshuffle of recombination may break up favorable combinations of genes; and since males do not directly increase the number of offspring in the next generation, an asexual population can out-breed and displace in as little as 50 generations a sexual population that is equal in every other respect. Nevertheless, the great majority of animals, plants, fungi and protists reproduce sexually. There is strong evidence that sexual reproduction arose early in the history of eukaryotes and that the genes controlling it have changed very little since then. How sexual reproduction evolved and survived is an unsolved puzzle.

The Red Queen hypothesis suggests that sexual reproduction provides protection against parasites, because it is easier for parasites to evolve means of overcoming the defenses of genetically identical clones than those of sexual species that present moving targets, and there is some experimental evidence for this. However, there is still doubt about whether it would explain the survival of sexual species if multiple similar clone species were present, as one of the clones may survive the attacks of parasites for long enough to out-breed the sexual species. Furthermore, contrary to the expectations of the Red Queen hypothesis, Kathryn A. Hanley et al. found that the prevalence, abundance and mean intensity of mites was significantly higher in sexual geckos than in asexuals sharing the same habitat. In addition, biologist Matthew Parker, after reviewing numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance, failed to find a single example consistent with the concept that pathogens are the primary selective agent responsible for sexual reproduction in the host.

Alexey Kondrashov's deterministic mutation hypothesis (DMH) assumes that each organism has more than one harmful mutation and the combined effects of these mutations are more harmful than the sum of the harm done by each individual mutation. If so, sexual recombination of genes will reduce the harm that bad mutations do to offspring and at the same time eliminate some bad mutations from the gene pool by isolating them in individuals that perish quickly because they have an above-average number of bad mutations. However, the evidence suggests that the DMH's assumptions are shaky because many species have on average less than one harmful mutation per individual and no species that has been investigated shows evidence of synergy between harmful mutations.

The random nature of recombination causes the relative abundance of alternative traits to vary from one generation to another. This genetic drift is insufficient on its own to make sexual reproduction advantageous, but a combination of genetic drift and natural selection may be sufficient. When chance produces combinations of good traits, natural selection gives a large advantage to lineages in which these traits become genetically linked. On the other hand, the benefits of good traits are neutralized if they appear along with bad traits. Sexual recombination gives good traits the opportunities to become linked with other good traits, and mathematical models suggest this may be more than enough to offset the disadvantages of sexual reproduction. Other combinations of hypotheses that are inadequate on their own are also being examined.

The adaptive function of sex remains a major unresolved issue in biology. The competing models to explain it were reviewed by John A. Birdsell and Christopher Wills. The hypotheses discussed above all depend on the possible beneficial effects of random genetic variation produced by genetic recombination. An alternative view is that sex arose and is maintained as a process for repairing DNA damage, and that the genetic variation produced is an occasionally beneficial byproduct.

Multicellularity

The simplest definitions of "multicellular," for example "having multiple cells," could include colonial cyanobacteria like Nostoc. Even a technical definition such as "having the same genome but different types of cell" would still include some genera of the green algae Volvox, which have cells that specialize in reproduction. Multicellularity evolved independently in organisms as diverse as sponges and other animals, fungi, plants, brown algae, cyanobacteria, slime molds and myxobacteria. For the sake of brevity, this article focuses on the organisms that show the greatest specialization of cells and variety of cell types, although this approach to the evolution of biological complexity could be regarded as "rather anthropocentric."

The initial advantages of multicellularity may have included: more efficient sharing of nutrients that are digested outside the cell, increased resistance to predators, many of which attacked by engulfing; the ability to resist currents by attaching to a firm surface; the ability to reach upwards to filter-feed or to obtain sunlight for photosynthesis; the ability to create an internal environment that gives protection against the external one; and even the opportunity for a group of cells to behave "intelligently" by sharing information. These features would also have provided opportunities for other organisms to diversify, by creating more varied environments than flat microbial mats could.

Multicellularity with differentiated cells is beneficial to the organism as a whole but disadvantageous from the point of view of individual cells, most of which lose the opportunity to reproduce themselves. In an asexual multicellular organism, rogue cells which retain the ability to reproduce may take over and reduce the organism to a mass of undifferentiated cells. Sexual reproduction eliminates such rogue cells from the next generation and therefore appears to be a prerequisite for complex multicellularity.

The available evidence indicates that eukaryotes evolved much earlier but remained inconspicuous until a rapid diversification around 1 Ga. The only respect in which eukaryotes clearly surpass bacteria and archaea is their capacity for variety of forms, and sexual reproduction enabled eukaryotes to exploit that advantage by producing organisms with multiple cells that differed in form and function.

By comparing the composition of transcription factor families and regulatory network motifs between unicellular organisms and multicellular organisms, scientists found there are many novel transcription factor families and three novel types of regulatory network motifs in multicellular organisms, and novel family transcription factors are preferentially wired into these novel network motifs which are essential for multicullular development. These results propose a plausible mechanism for the contribution of novel-family transcription factors and novel network motifs to the origin of multicellular organisms at transcriptional regulatory level.

Fossil evidence

The Francevillian biota fossils, dated to 2.1 Ga, are the earliest known fossil organisms that are clearly multicellular. They may have had differentiated cells. Another early multicellular fossil, Qingshania, dated to 1.7 Ga, appears to consist of virtually identical cells. The red algae called Bangiomorpha, dated at 1.2 Ga, is the earliest known organism that certainly has differentiated, specialized cells, and is also the oldest known sexually reproducing organism. The 1.43 billion-year-old fossils interpreted as fungi appear to have been multicellular with differentiated cells. The "string of beads" organism Horodyskia, found in rocks dated from 1.5 Ga to 900 Ma, may have been an early metazoan; however, it has also been interpreted as a colonial foraminiferan.

Emergence of animals

Animals are multicellular eukaryotes, and are distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls. All animals are motile, if only at certain life stages. All animals except sponges have bodies differentiated into separate tissues, including muscles, which move parts of the animal by contracting, and nerve tissue, which transmits and processes signals. In November 2019, researchers reported the discovery of Caveasphaera, a multicellular organism found in 609-million-year-old rocks, that is not easily defined as an animal or non-animal, which may be related to one of the earliest instances of animal evolution. Fossil studies of Caveasphaera have suggested that animal-like embryonic development arose much earlier than the oldest clearly defined animal fossils. and may be consistent with studies suggesting that animal evolution may have begun about 750 million years ago.

Nonetheless, the earliest widely accepted animal fossils are the rather modern-looking cnidarians (the group that includes jellyfish, sea anemones and Hydra), possibly from around 580 Ma, although fossils from the Doushantuo Formation can only be dated approximately. Their presence implies that the cnidarian and bilaterian lineages had already diverged.

The Ediacara biota, which flourished for the last 40 million years before the start of the Cambrian, were the first animals more than a very few centimetres long. Many were flat and had a "quilted" appearance, and seemed so strange that there was a proposal to classify them as a separate kingdom, Vendozoa. Others, however, have been interpreted as early molluscs (Kimberella), echinoderms (Arkarua), and arthropods (Spriggina, Parvancorina). There is still debate about the classification of these specimens, mainly because the diagnostic features which allow taxonomists to classify more recent organisms, such as similarities to living organisms, are generally absent in the Ediacarans. However, there seems little doubt that Kimberella was at least a triploblastic bilaterian animal, in other words, an animal significantly more complex than the cnidarians.

The small shelly fauna are a very mixed collection of fossils found between the Late Ediacaran and Middle Cambrian periods. The earliest, Cloudina, shows signs of successful defense against predation and may indicate the start of an evolutionary arms race. Some tiny Early Cambrian shells almost certainly belonged to molluscs, while the owners of some "armor plates," Halkieria and Microdictyon, were eventually identified when more complete specimens were found in Cambrian lagerstätten that preserved soft-bodied animals.

In the 1970s there was already a debate about whether the emergence of the modern phyla was "explosive" or gradual but hidden by the shortage of Precambrian animal fossils. A re-analysis of fossils from the Burgess Shale lagerstätte increased interest in the issue when it revealed animals, such as Opabinia, which did not fit into any known phylum. At the time these were interpreted as evidence that the modern phyla had evolved very rapidly in the Cambrian explosion and that the Burgess Shale's "weird wonders" showed that the Early Cambrian was a uniquely experimental period of animal evolution. Later discoveries of similar animals and the development of new theoretical approaches led to the conclusion that many of the "weird wonders" were evolutionary "aunts" or "cousins" of modern groups—for example that Opabinia was a member of the lobopods, a group which includes the ancestors of the arthropods, and that it may have been closely related to the modern tardigrades. Nevertheless, there is still much debate about whether the Cambrian explosion was really explosive and, if so, how and why it happened and why it appears unique in the history of animals.

Deuterostomes and the first vertebrates

Most of the animals at the heart of the Cambrian explosion debate are protostomes, one of the two main groups of complex animals. The other major group, the deuterostomes, contains invertebrates such as starfish and sea urchins (echinoderms), as well as chordates (see below). Many echinoderms have hard calcite "shells," which are fairly common from the Early Cambrian small shelly fauna onwards. Other deuterostome groups are soft-bodied, and most of the significant Cambrian deuterostome fossils come from the Chengjiang fauna, a lagerstätte in China. The chordates are another major deuterostome group: animals with a distinct dorsal nerve cord. Chordates include soft-bodied invertebrates such as tunicates as well as vertebrates—animals with a backbone. While tunicate fossils predate the Cambrian explosion, the Chengjiang fossils Haikouichthys and Myllokunmingia appear to be true vertebrates, and Haikouichthys had distinct vertebrae, which may have been slightly mineralized. Vertebrates with jaws, such as the acanthodians, first appeared in the Late Ordovician.

Colonization of land

Adaptation to life on land is a major challenge: all land organisms need to avoid drying-out and all those above microscopic size must create special structures to withstand gravity; respiration and gas exchange systems have to change; reproductive systems cannot depend on water to carry eggs and sperm towards each other. Although the earliest good evidence of land plants and animals dates back to the Ordovician period (488 to 444 Ma), and a number of microorganism lineages made it onto land much earlier, modern land ecosystems only appeared in the Late Devonian, about 385 to 359 Ma. In May 2017, evidence of the earliest known life on land may have been found in 3.48-billion-year-old geyserite and other related mineral deposits (often found around hot springs and geysers) uncovered in the Pilbara Craton of Western Australia. In July 2018, scientists reported that the earliest life on land may have been bacteria living on land 3.22 billion years ago. In May 2019, scientists reported the discovery of a fossilized fungus, named Ourasphaira giraldae, in the Canadian Arctic, that may have grown on land a billion years ago, well before plants were living on land.

Evolution of terrestrial antioxidants

Oxygen began to accumulate in Earth's atmosphere over 3 Ga, as a by-product of photosynthesis in cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). However, oxygen produces destructive chemical oxydation which was toxic to most previous organisms. Protective endogenous antioxidant enzymes and exogenous dietary antioxidants helped to prevent oxidative damage. For example, brown algae accumulate inorganic mineral antioxidants such as rubidium, vanadium, zinc, iron, copper, molybdenum, selenium and iodine, concentrated more than 30,000 times more than in seawater. Most marine mineral antioxidants act in the cells as essential trace elements in redox and antioxidant metalloenzymes.

When plants and animals began to enter rivers and land about 500 Ma, environmental deficiency of these marine mineral antioxidants was a challenge to the evolution of terrestrial life. Terrestrial plants slowly optimized the production of new endogenous antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, polyphenols, flavonoids, tocopherols, etc.

A few of these appeared more recently, in last 200–50 Ma, in fruits and flowers of angiosperm plants. In fact, angiosperms (the dominant type of plant today) and most of their antioxidant pigments evolved during the Late Jurassic period. Plants employ antioxidants to defend their structures against reactive oxygen species produced during photosynthesis. Animals are exposed to the same oxidants, and they have evolved endogenous enzymatic antioxidant systems. Iodine in the form of the iodide ion I- is the most primitive and abundant electron-rich essential element in the diet of marine and terrestrial organisms; it acts as an electron donor and has this ancestral antioxidant function in all iodide-concentrating cells, from primitive marine algae to terrestrial vertebrates.

Evolution of soil

Before the colonization of land there was no soil, a combination of mineral particles and decomposed organic matter. Land surfaces were either bare rock or shifting sand produced by weathering. Water and dissolved nutrients would have drained away very quickly. In the Sub-Cambrian peneplain in Sweden, for example, maximum depth of kaolinitization by Neoproterozoic weathering is about 5 m, while nearby kaolin deposits developed in the Mesozoic are much thicker. It has been argued that in the late Neoproterozoic sheet wash was a dominant process of erosion of surface material due to the lack of plants on land.

Films of cyanobacteria, which are not plants but use the same photosynthesis mechanisms, have been found in modern deserts in areas unsuitable for vascular plants. This suggests that microbial mats may have been the first organisms to colonize dry land, possibly in the Precambrian. Mat-forming cyanobacteria could have gradually evolved resistance to desiccation as they spread from the seas to intertidal zones and then to land. Lichens, which are symbiotic combinations of a fungus (almost always an ascomycete) and one or more photosynthesizers (green algae or cyanobacteria), are also important colonizers of lifeless environments, and their ability to break down rocks contributes to soil formation where plants cannot survive. The earliest known ascomycete fossils date from 423 to 419 Ma in the Silurian.

Soil formation would have been very slow until the appearance of burrowing animals, which mix the mineral and organic components of soil and whose feces are a major source of organic components. Burrows have been found in Ordovician sediments, and are attributed to annelids (worms) or arthropods.

Plants and the Late Devonian wood crisis

In aquatic algae, almost all cells are capable of photosynthesis and are nearly independent. Life on land required plants to become internally more complex and specialized: photosynthesis is most efficient at the top; roots extract water and nutrients from the ground; and the intermediate parts support and transport.

Spores of land plants resembling liverworts have been found in Middle Ordovician rocks from 476 Ma. Middle Silurian rocks from 430 Ma contain fossils of true plants, including clubmosses such as Baragwanathia; most were under 10 centimetres (3.9 in) high, and some appear closely related to vascular plants, the group that includes trees.

By the Late Devonian 370 Ma, abundant trees such as Archaeopteris bound the soil so firmly that they changed river systems from mostly braided to mostly meandering. This caused the "Late Devonian wood crisis" because:

- They removed more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, reducing the greenhouse effect and thus causing an ice age in the Carboniferous period. This did not repeat in later ecosystems, since the carbon dioxide "locked up" in wood was returned to the atmosphere by decomposition of dead wood, but the earliest fossil evidence of fungi that can decompose wood also comes from the Late Devonian.

- The increasing depth of plants' roots led to more washing of nutrients into rivers and seas by rain. This caused algal blooms whose high consumption of oxygen caused anoxic events in deeper waters, increasing the extinction rate among deep-water animals.

Land invertebrates

Animals had to change their feeding and excretory systems, and most land animals developed internal fertilization of their eggs. The difference in refractive index between water and air required changes in their eyes. On the other hand, in some ways movement and breathing became easier, and the better transmission of high-frequency sounds in air encouraged the development of hearing.

The oldest known air-breathing animal is Pneumodesmus, an archipolypodan millipede from the Middle Silurian, about 428 Ma. Its air-breathing, terrestrial nature is evidenced by the presence of spiracles, the openings to tracheal systems. However, some earlier trace fossils from the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary about 490 Ma are interpreted as the tracks of large amphibious arthropods on coastal sand dunes, and may have been made by euthycarcinoids, which are thought to be evolutionary "aunts" of myriapods. Other trace fossils from the Late Ordovician a little over 445 Ma probably represent land invertebrates, and there is clear evidence of numerous arthropods on coasts and alluvial plains shortly before the Silurian-Devonian boundary, about 415 Ma, including signs that some arthropods ate plants. Arthropods were well pre-adapted to colonise land, because their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.

The fossil record of other major invertebrate groups on land is poor: none at all for non-parasitic flatworms, nematodes or nemerteans; some parasitic nematodes have been fossilized in amber; annelid worm fossils are known from the Carboniferous, but they may still have been aquatic animals; the earliest fossils of gastropods on land date from the Late Carboniferous, and this group may have had to wait until leaf litter became abundant enough to provide the moist conditions they need.

The earliest confirmed fossils of flying insects date from the Late Carboniferous, but it is thought that insects developed the ability to fly in the Early Carboniferous or even Late Devonian. This gave them a wider range of ecological niches for feeding and breeding, and a means of escape from predators and from unfavorable changes in the environment. About 99% of modern insect species fly or are descendants of flying species.

Early land vertebrates

Tetrapods, vertebrates with four limbs, evolved from other rhipidistian fish over a relatively short timespan during the Late Devonian (370 to 360 Ma). The early groups are grouped together as Labyrinthodontia. They retained aquatic, fry-like tadpoles, a system still seen in modern amphibians.

Iodine and T4/T3 stimulate the amphibian metamorphosis and the evolution of nervous systems transforming the aquatic, vegetarian tadpole into a "more evolved" terrestrial, carnivorous frog with better neurological, visuospatial, olfactory and cognitive abilities for hunting. The new hormonal action of T3 was made possible by the formation of T3-receptors in the cells of vertebrates. Firstly, about 600-500 million years ago, in primitive Chordata appeared the alpha T3-receptors with a metamorphosing action and then, about 250-150 million years ago, in the Birds and Mammalia appeared the beta T3-receptors with metabolic and thermogenetic actions.

From the 1950s to the early 1980s it was thought that tetrapods evolved from fish that had already acquired the ability to crawl on land, possibly in order to go from a pool that was drying out to one that was deeper. However, in 1987, nearly complete fossils of Acanthostega from about 363 Ma showed that this Late Devonian transitional animal had legs and both lungs and gills, but could never have survived on land: its limbs and its wrist and ankle joints were too weak to bear its weight; its ribs were too short to prevent its lungs from being squeezed flat by its weight; its fish-like tail fin would have been damaged by dragging on the ground. The current hypothesis is that Acanthostega, which was about 1 metre (3.3 ft) long, was a wholly aquatic predator that hunted in shallow water. Its skeleton differed from that of most fish, in ways that enabled it to raise its head to breathe air while its body remained submerged, including: its jaws show modifications that would have enabled it to gulp air; the bones at the back of its skull are locked together, providing strong attachment points for muscles that raised its head; the head is not joined to the shoulder girdle and it has a distinct neck.

The Devonian proliferation of land plants may help to explain why air breathing would have been an advantage: leaves falling into streams and rivers would have encouraged the growth of aquatic vegetation; this would have attracted grazing invertebrates and small fish that preyed on them; they would have been attractive prey but the environment was unsuitable for the big marine predatory fish; air-breathing would have been necessary because these waters would have been short of oxygen, since warm water holds less dissolved oxygen than cooler marine water and since the decomposition of vegetation would have used some of the oxygen.

Later discoveries revealed earlier transitional forms between Acanthostega and completely fish-like animals. Unfortunately, there is then a gap (Romer's gap) of about 30 Ma between the fossils of ancestral tetrapods and Middle Carboniferous fossils of vertebrates that look well-adapted for life on land, during which only some fossils are found, which had five digits in the terminating point of the four limbs, showing true or crown tetrapods appeared in the gap around 350 Ma. Some of the fossils after this gap look as if the animals which they belonged to were early relatives of modern amphibians, all of which need to keep their skins moist and to lay their eggs in water, while others are accepted as early relatives of the amniotes, whose waterproof skin and egg membranes enable them to live and breed far from water. The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse may have paved the way for amniotes to become dominant over amphibians.

Dinosaurs, birds and mammals

Amniotes, whose eggs can survive in dry environments, probably evolved in the Late Carboniferous period (330 to 298.9 Ma). The earliest fossils of the two surviving amniote groups, synapsids and sauropsids, date from around 313 Ma. The synapsid pelycosaurs and their descendants the therapsids are the most common land vertebrates in the best-known Permian (298.9 to 251.902 Ma) fossil beds. However, at the time these were all in temperate zones at middle latitudes, and there is evidence that hotter, drier environments nearer the Equator were dominated by sauropsids and amphibians.

The Permian–Triassic extinction event wiped out almost all land vertebrates, as well as the great majority of other life. During the slow recovery from this catastrophe, estimated to have taken 30 million years, a previously obscure sauropsid group became the most abundant and diverse terrestrial vertebrates: a few fossils of archosauriformes ("ruling lizard forms") have been found in Late Permian rocks, but, by the Middle Triassic, archosaurs were the dominant land vertebrates. Dinosaurs distinguished themselves from other archosaurs in the Late Triassic, and became the dominant land vertebrates of the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods (201.3 to 66 Ma).

During the Late Jurassic, birds evolved from small, predatory theropod dinosaurs. The first birds inherited teeth and long, bony tails from their dinosaur ancestors, but some had developed horny, toothless beaks by the very Late Jurassic and short pygostyle tails by the Early Cretaceous.

While the archosaurs and dinosaurs were becoming more dominant in the Triassic, the mammaliaform successors of the therapsids evolved into small, mainly nocturnal insectivores. This ecological role may have promoted the evolution of mammals, for example nocturnal life may have accelerated the development of endothermy ("warm-bloodedness") and hair or fur. By 195 Ma in the Early Jurassic there were animals that were very like today's mammals in a number of respects. Unfortunately, there is a gap in the fossil record throughout the Middle Jurassic. However, fossil teeth discovered in Madagascar indicate that the split between the lineage leading to monotremes and the one leading to other living mammals had occurred by 167 Ma. After dominating land vertebrate niches for about 150 Ma, the non-avian dinosaurs perished in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (66 Ma) along with many other groups of organisms. Mammals throughout the time of the dinosaurs had been restricted to a narrow range of taxa, sizes and shapes, but increased rapidly in size and diversity after the extinction, with bats taking to the air within 13 million years, and cetaceans to the sea within 15 million years.

Flowering plants

The first flowering plants appeared around 130 Ma. The 250,000 to 400,000 species of flowering plants outnumber all other ground plants combined, and are the dominant vegetation in most terrestrial ecosystems. There is fossil evidence that flowering plants diversified rapidly in the Early Cretaceous, from 130 to 90 Mya, and that their rise was associated with that of pollinating insects. Among modern flowering plants Magnolia are thought to be close to the common ancestor of the group. However, paleontologists have not succeeded in identifying the earliest stages in the evolution of flowering plants.

Social insects

The social insects are remarkable because the great majority of individuals in each colony are sterile. This appears contrary to basic concepts of evolution such as natural selection and the selfish gene. In fact, there are very few eusocial insect species: only 15 out of approximately 2,600 living families of insects contain eusocial species, and it seems that eusociality has evolved independently only 12 times among arthropods, although some eusocial lineages have diversified into several families. Nevertheless, social insects have been spectacularly successful; for example although ants and termites account for only about 2% of known insect species, they form over 50% of the total mass of insects. Their ability to control a territory appears to be the foundation of their success.

The sacrifice of breeding opportunities by most individuals has long been explained as a consequence of these species' unusual haplodiploid method of sex determination, which has the paradoxical consequence that two sterile worker daughters of the same queen share more genes with each other than they would with their offspring if they could breed. However, E. O. Wilson and Bert Hölldobler argue that this explanation is faulty: for example, it is based on kin selection, but there is no evidence of nepotism in colonies that have multiple queens. Instead, they write, eusociality evolves only in species that are under strong pressure from predators and competitors, but in environments where it is possible to build "fortresses"; after colonies have established this security, they gain other advantages through co-operative foraging. In support of this explanation they cite the appearance of eusociality in bathyergid mole rats, which are not haplodiploid.

The earliest fossils of insects have been found in Early Devonian rocks from about 400 Ma, which preserve only a few varieties of flightless insect. The Mazon Creek lagerstätten from the Late Carboniferous, about 300 Ma, include about 200 species, some gigantic by modern standards, and indicate that insects had occupied their main modern ecological niches as herbivores, detritivores and insectivores. Social termites and ants first appear in the Early Cretaceous, and advanced social bees have been found in Late Cretaceous rocks but did not become abundant until the Middle Cenozoic.

Humans

The idea that, along with other life forms, modern-day humans evolved from an ancient, common ancestor was proposed by Robert Chambers in 1844 and taken up by Charles Darwin in 1871. Modern humans evolved from a lineage of upright-walking apes that has been traced back over 6 Ma to Sahelanthropus. The first known stone tools were made about 2.5 Ma, apparently by Australopithecus garhi, and were found near animal bones that bear scratches made by these tools. The earliest hominines had chimpanzee-sized brains, but there has been a fourfold increase in the last 3 Ma; a statistical analysis suggests that hominine brain sizes depend almost completely on the date of the fossils, while the species to which they are assigned has only slight influence. There is a long-running debate about whether modern humans evolved all over the world simultaneously from existing advanced hominines or are descendants of a single small population in Africa, which then migrated all over the world less than 200,000 years ago and replaced previous hominine species. There is also debate about whether anatomically modern humans had an intellectual, cultural and technological "Great Leap Forward" under 100,000 years ago and, if so, whether this was due to neurological changes that are not visible in fossils.

Mass extinctions

Life on Earth has suffered occasional mass extinctions at least since 542 Ma. Although they were disasters at the time, mass extinctions have sometimes accelerated the evolution of life on Earth. When dominance of particular ecological niches passes from one group of organisms to another, it is rarely because the new dominant group is "superior" to the old and usually because an extinction event eliminates the old dominant group and makes way for the new one.

The fossil record appears to show that the gaps between mass extinctions are becoming longer and the average and background rates of extinction are decreasing. Both of these phenomena could be explained in one or more ways:

- The oceans may have become more hospitable to life over the last 500 Ma and less vulnerable to mass extinctions: dissolved oxygen became more widespread and penetrated to greater depths; the development of life on land reduced the run-off of nutrients and hence the risk of eutrophication and anoxic events; and marine ecosystems became more diversified so that food chains were less likely to be disrupted.

- Reasonably complete fossils are very rare, most extinct organisms are represented only by partial fossils, and complete fossils are rarest in the oldest rocks. So paleontologists have mistakenly assigned parts of the same organism to different genera, which were often defined solely to accommodate these finds—the story of Anomalocaris is an example of this. The risk of this mistake is higher for older fossils because these are often both unlike parts of any living organism and poorly conserved. Many of the "superfluous" genera are represented by fragments which are not found again and the "superfluous" genera appear to become extinct very quickly.

Biodiversity in the fossil record, which is "...the number of distinct genera alive at any given time; that is, those whose first occurrence predates and whose last occurrence postdates that time" shows a different trend: a fairly swift rise from 542 to 400 Ma; a slight decline from 400 to 200 Ma, in which the devastating Permian–Triassic extinction event is an important factor; and a swift rise from 200 Ma to the present.