A quantity is subject to exponential decay if it decreases at a rate proportional to its current value. Symbolically, this process can be expressed by the following differential equation, where N is the quantity and λ (lambda) is a positive rate called the exponential decay constant:

The solution to this equation (see derivation below) is:

where N(t) is the quantity at time t, N0 = N(0) is the initial quantity, that is, the quantity at time t = 0, and the constant λ is called the decay constant, disintegration constant, rate constant, or transformation constant.

Measuring rates of decay

Mean lifetime

If the decaying quantity, N(t), is the number of discrete elements in a certain set, it is possible to compute the average length of time that an element remains in the set. This is called the mean lifetime (or simply the lifetime), where the exponential time constant, , relates to the decay rate, λ, in the following way:

The mean lifetime can be looked at as a "scaling time", because the exponential decay equation can be written in terms of the mean lifetime, , instead of the decay constant, λ:

and that is the time at which the population of the assembly is reduced to 1/e ≈ 0.367879441 times its initial value.

For example, if the initial population of the assembly, N(0), is 1000, then the population at time , , is 368.

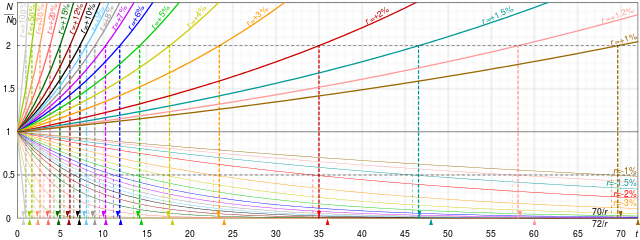

A very similar equation will be seen below, which arises when the base of the exponential is chosen to be 2, rather than e. In that case the scaling time is the "half-life".

Half-life

A more intuitive characteristic of exponential decay for many people is the time required for the decaying quantity to fall to one half of its initial value. (If N(t) is discrete, then this is the median life-time rather than the mean life-time.) This time is called the half-life, and often denoted by the symbol t1/2. The half-life can be written in terms of the decay constant, or the mean lifetime, as:

When this expression is inserted for in the exponential equation above, and ln 2 is absorbed into the base, this equation becomes:

Thus, the amount of material left is 2−1 = 1/2 raised to the (whole or fractional) number of half-lives that have passed. Thus, after 3 half-lives there will be 1/23 = 1/8 of the original material left.

Therefore, the mean lifetime is equal to the half-life divided by the natural log of 2, or:

For example, polonium-210 has a half-life of 138 days, and a mean lifetime of 200 days.

Solution of the differential equation

The equation that describes exponential decay is

or, by rearranging (applying the technique called separation of variables),

Integrating, we have

where C is the constant of integration, and hence

where the final substitution, N0 = eC, is obtained by evaluating the equation at t = 0, as N0 is defined as being the quantity at t = 0.

This is the form of the equation that is most commonly used to describe exponential decay. Any one of decay constant, mean lifetime, or half-life is sufficient to characterise the decay. The notation λ for the decay constant is a remnant of the usual notation for an eigenvalue. In this case, λ is the eigenvalue of the negative of the differential operator with N(t) as the corresponding eigenfunction. The units of the decay constant are s−1.

Derivation of the mean lifetime

Given an assembly of elements, the number of which decreases ultimately to zero, the mean lifetime, , (also called simply the lifetime) is the expected value of the amount of time before an object is removed from the assembly. Specifically, if the individual lifetime of an element of the assembly is the time elapsed between some reference time and the removal of that element from the assembly, the mean lifetime is the arithmetic mean of the individual lifetimes.

Starting from the population formula

first let c be the normalizing factor to convert to a probability density function:

or, on rearranging,

Exponential decay is a scalar multiple of the exponential distribution (i.e. the individual lifetime of each object is exponentially distributed), which has a well-known expected value. We can compute it here using integration by parts.

Decay by two or more processes

A quantity may decay via two or more different processes simultaneously. In general, these processes (often called "decay modes", "decay channels", "decay routes" etc.) have different probabilities of occurring, and thus occur at different rates with different half-lives, in parallel. The total decay rate of the quantity N is given by the sum of the decay routes; thus, in the case of two processes:

The solution to this equation is given in the previous section, where the sum of is treated as a new total decay constant .

Partial mean life associated with individual processes is by definition the multiplicative inverse of corresponding partial decay constant: . A combined can be given in terms of s:

Since half-lives differ from mean life by a constant factor, the same equation holds in terms of the two corresponding half-lives:

where is the combined or total half-life for the process, and are so-named partial half-lives of corresponding processes. Terms "partial half-life" and "partial mean life" denote quantities derived from a decay constant as if the given decay mode were the only decay mode for the quantity. The term "partial half-life" is misleading, because it cannot be measured as a time interval for which a certain quantity is halved.

In terms of separate decay constants, the total half-life can be shown to be

For a decay by three simultaneous exponential processes the total half-life can be computed as above:

Decay series / coupled decay

In nuclear science and pharmacokinetics, the agent of interest might be situated in a decay chain, where the accumulation is governed by exponential decay of a source agent, while the agent of interest itself decays by means of an exponential process.

These systems are solved using the Bateman equation.

In the pharmacology setting, some ingested substances might be absorbed into the body by a process reasonably modeled as exponential decay, or might be deliberately formulated to have such a release profile.

Applications and examples

Exponential decay occurs in a wide variety of situations. Most of these fall into the domain of the natural sciences.

Many decay processes that are often treated as exponential, are really only exponential so long as the sample is large and the law of large numbers holds. For small samples, a more general analysis is necessary, accounting for a Poisson process.

Natural sciences

- Chemical reactions: The rates of certain types of chemical reactions depend on the concentration of one or another reactant. Reactions whose rate depends only on the concentration of one reactant (known as first-order reactions) consequently follow exponential decay. For instance, many enzyme-catalyzed reactions behave this way.

- Electrostatics: The electric charge (or, equivalently, the potential) contained in a capacitor (capacitance C) changes exponentially, if the capacitor experiences a constant external load (resistance R). The exponential time-constant τ for the process is R C, and the half-life is therefore R C ln2. This applies to both charging and discharging, i.e. a capacitor charges or discharges according to the same law. The same equations can be applied to the current in an inductor. (Furthermore, the particular case of a capacitor or inductor changing through several parallel resistors makes an interesting example of multiple decay processes, with each resistor representing a separate process. In fact, the expression for the equivalent resistance of two resistors in parallel mirrors the equation for the half-life with two decay processes.)

- Geophysics: Atmospheric pressure decreases approximately exponentially with increasing height above sea level, at a rate of about 12% per 1000m.

- Heat transfer: If an object at one temperature is exposed to a medium of another temperature, the temperature difference between the object and the medium follows exponential decay (in the limit of slow processes; equivalent to "good" heat conduction inside the object, so that its temperature remains relatively uniform through its volume). See also Newton's law of cooling.

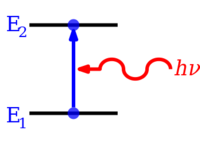

- Luminescence: After excitation, the emission intensity – which is proportional to the number of excited atoms or molecules – of a luminescent material decays exponentially. Depending on the number of mechanisms involved, the decay can be mono- or multi-exponential.

- Pharmacology and toxicology: It is found that many administered substances are distributed and metabolized (see clearance) according to exponential decay patterns. The biological half-lives "alpha half-life" and "beta half-life" of a substance measure how quickly a substance is distributed and eliminated.

- Physical optics: The intensity of electromagnetic radiation such as light or X-rays or gamma rays in an absorbent medium, follows an exponential decrease with distance into the absorbing medium. This is known as the Beer-Lambert law.

- Radioactivity: In a sample of a radionuclide that undergoes radioactive decay to a different state, the number of atoms in the original state follows exponential decay as long as the remaining number of atoms is large. The decay product is termed a radiogenic nuclide.

- Thermoelectricity: The decline in resistance of a Negative Temperature Coefficient Thermistor as temperature is increased.

- Vibrations: Some vibrations may decay exponentially; this characteristic is often found in damped mechanical oscillators, and used in creating ADSR envelopes in synthesizers. An overdamped system will simply return to equilibrium via an exponential decay.

- Beer froth: Arnd Leike, of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, won an Ig Nobel Prize for demonstrating that beer froth obeys the law of exponential decay.

Social sciences

- Finance: a retirement fund will decay exponentially being subject to discrete payout amounts, usually monthly, and an input subject to a continuous interest rate. A differential equation dA/dt = input – output can be written and solved to find the time to reach any amount A, remaining in the fund.

- In simple glottochronology, the (debatable) assumption of a constant decay rate in languages allows one to estimate the age of single languages. (To compute the time of split between two languages requires additional assumptions, independent of exponential decay).

Computer science

- The core routing protocol on the Internet, BGP, has to maintain a routing table in order to remember the paths a packet can be deviated to. When one of these paths repeatedly changes its state from available to not available (and vice versa), the BGP router controlling that path has to repeatedly add and remove the path record from its routing table (flaps the path), thus spending local resources such as CPU and RAM and, even more, broadcasting useless information to peer routers. To prevent this undesired behavior, an algorithm named route flapping damping assigns each route a weight that gets bigger each time the route changes its state and decays exponentially with time. When the weight reaches a certain limit, no more flapping is done, thus suppressing the route.