| |

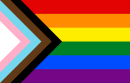

| LGBT Pride flag | |

| Use | Symbol of the LGBT community |

|---|---|

| Adopted | 1978 |

| Design | Striped flag, typically six colors (from top to bottom): red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. |

| Designed by | Gilbert Baker |

The rainbow flag is a symbol of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) pride and LGBT social movements. Also known as the gay pride flag or LGBT pride flag, the colors reflect the diversity of the LGBT community and the spectrum of human sexuality and gender. Using a rainbow flag as a symbol of gay pride began in San Francisco, California, but eventually became common at LGBT rights events worldwide.

Originally devised by artist Gilbert Baker, Lynn Segerblom, James McNamara and other activists, the design underwent several revisions after its debut in 1978, and continues to inspire variations. Although Baker's original rainbow flag had eight colors, from 1979 to the present day the most common variant consists of six stripes: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. The flag is typically displayed horizontally, with the red stripe on top, as it would be in a natural rainbow.

LGBT people and allies currently use rainbow flags and many rainbow-themed items and color schemes as an outward symbol of their identity or support. In addition to the rainbow, many other flags and symbols are used to communicate specific identities within the LGBT community.

History

Origin

Gilbert Baker, born in 1951 and raised in Parsons, Kansas, had served in the US Army between 1970 and 1972. After an honorable discharge, Baker taught himself to sew. In 1974, Baker met Harvey Milk, an influential gay leader, who later challenged Baker to devise a symbol of pride for the gay community. The original gay pride flags flew at the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade celebration on June 25, 1978. Prior to that event, the Pink triangle had been used as a symbol for the LGBT community, despite representing a dark chapter in the history of homosexuality. The Nazi regime had used the pink triangle to identify and stigmatize men interned as homosexuals in the concentration camps. Rather than relying on a Nazi tool of oppression, the community sought a new inspiring symbol.

A close friend of Baker's, independent filmmaker Arthur J. Bressan Jr., pressed him to create a new symbol at "the dawn of a new gay consciousness and freedom". According to a profile published in the Bay Area Reporter in 1985, Baker "chose the rainbow motif because of its associations with the hippie movement of the Sixties but he notes that the use of the design dates all the way back to ancient Egypt." People have speculated that Baker was inspired by the Judy Garland song "Over the Rainbow" (Garland being among the first gay icons), but when asked, Baker said that it was "more about the Rolling Stones and their song 'She's a Rainbow.'" Baker was likely influenced by the "Flag of the Races" (with five horizontal stripes: red, white, brown, yellow, and black) popular among the World peace and Hippie movement of the 1960s.

The first rainbow flags commissioned by the fledgling pride committee were produced by a team that included artist Lynn Segerblom. Segerblom was then known as Faerie Argyle Rainbow; according to her, she created the original dyeing process for the flags. Thirty volunteers hand-dyed and stitched the first two flags for the parade. The original flag design had eight stripes, with a specific meaning assigned to each of the colors:

| Hot pink | Sex | |

| Red | Life | |

| Orange | Healing | |

| Yellow | Sunlight | |

| Green | Nature | |

| Turquoise | Magic | |

| Indigo | Serenity | |

| Violet | Spirit |

The two flags originally created for the 1978 parade were believed lost for over four decades, until a remnant of one was discovered among Baker's belongings in 2020.

1978 to 1979

After the assassination of gay San Francisco City Supervisor Harvey Milk on November 27, 1978, demand for the rainbow flag greatly increased. In response, the Paramount Flag Company began selling a version using stock rainbow fabric with seven stripes: red, orange, yellow, green, turquoise, blue, and violet. As Baker ramped up production of his version of the flag, he too dropped the hot pink stripe because fabric in that color was not readily available. San Francisco-based Paramount Flag Co. also began selling a surplus stock of Rainbow Girls flags from its retail store on the southwest corner of Polk and Post, at which Gilbert Baker was an employee.

In 1979, the flag was modified again. Aiming to decorate the street lamps along the parade route with hundreds of rainbow banners, Baker decided to split the motif in two with an even number of stripes flanking each lamp pole. To achieve this effect, he dropped the turquoise stripe that had been used in the seven-stripe flag. The result was the six-stripe version of the flag that would become the standard for future production—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet.

1980s to 2000s

In 1989, the rainbow flag came to further nationwide attention in the U.S. after John Stout sued his landlords and won when they attempted to prohibit him from displaying the flag from his West Hollywood, California, apartment balcony.

In 2000, the University of Hawaii at Manoa changed its sports teams' name from "Rainbow Warriors" to "Warriors" and redesigned its logo to eliminate a rainbow from it. Athletic director Hugh Yoshida initially said that the change was to distance the school's athletic program from homosexuality. When this drew criticism, Yoshida then said the change was merely to avoid brand confusion. The school then allowed each team to select its own name, leading to a mix including "Rainbow Warriors", "Warriors", "Rainbows" and "Rainbow Wahine". This decision was reversed in February 2013, by athletic director Ben Jay, dictating that all men's athletic teams be nicknamed "Warriors" and all women's teams "Rainbow Warriors". In May 2013, all teams were once again called "Rainbow Warriors" regardless of sex.

In recognition of the 25th anniversary of the rainbow flag, during gay pride celebrations in June 2003, Gilbert Baker restored the rainbow flag back to its original eight-striped version and advocated that others do the same.

In autumn 2004 several gay businesses in London were ordered by Westminster City Council to remove the rainbow flag from their premises, as its display required planning permission. When one shop applied for permission, the Planning sub-committee refused the application on the chair's casting vote (May 19, 2005), a decision condemned by gay councillors in Westminster and the then Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone. In November the council announced a reversal of policy, stating that most shops and bars would be allowed to fly the rainbow flag without planning permission.

In June 2004 LGBT activists sailed to Australia's uninhabited Coral Sea Islands Territory and raised the rainbow flag, proclaiming the territory independent of Australia, calling it the Gay and Lesbian Kingdom of the Coral Sea Islands in protest to the Australian government's refusal to recognize same-sex marriages. The rainbow flag was the official flag of the claimed kingdom until its dissolution in 2017 following the legalisation of same sex marriage in Australia.

2010s to present

In June 2015, The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan acquired the rainbow flag symbol as part of its design collection.

On June 26, 2015, the White House was illuminated in the rainbow flag colors to commemorate the legalization of same-sex marriages in all 50 U.S. states, following the Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court decision.

An emoji version of the flag ( 🏳️🌈 ) was formally proposed in July 2016, and released that November.

Gilbert Baker unveiled his final version of the rainbow flag in early 2017; in response to the election of Donald Trump, Baker added a ninth stripe in lavender (above the hot pink stripe) to represent diversity.

A portion of one of the original 1978 rainbow flags was donated to the GLBT Historical Society Museum and Archives in San Francisco in April 2021; the section is the only known surviving remnant of the two inaugural eight-color rainbow flags.

Polish nationalists trampled, spat on, and burned the rainbow flag during Independence Day marches in Warsaw in the 2020s. In one case a mob burned down a residential building because it was flying a rainbow flag and had a Women's Strike sign.

Transnationalism

The rainbow flag has been repurposed to manifest a multitude of transnational and globalized ways of being queer. In a few scholarly articles, the rainbow flag is described as a "floating signifier". A floating signifier refers to the person giving the object its interpreted meaning and significance. Flags are ambivalent symbols that hold different ideologies, meanings, and agendas depending on the beholder. Therefore, the rainbow flag is a boundary object that not only brings together queer communities locally and transnationally, but can also create debates and conflicts.

In March 2016, rainbow stamps were created by a postal service common to Sweden and Denmark celebrating pride traversing borders internationally. It has become common to display a rainbow in store fronts or on websites to indicate that the space is queer friendly. Many government official buildings in different countries in Europe and America display the rainbow flag.

In some countries, such as Saudi Arabia, it's illegal or sell (or wear) some "rainbow-colored" stuff, since it's claimed to "indirectly promote homosexuality" and claimed to "contradict normal common sense".

Rainbow colors as a symbol of LGBT pride

There have been many activism statements made with using the rainbow colors to create "hidden flags", in order to express their political agenda and support for gay rights and diversity. For example, in Poland on August 6, 2020, President Andrzej Duda was sworn in for a second term supporting an anti-LGBTQ+ campaign and the opposing politicians planned beforehand to coordinate and wear a colored outfit to each represent a color of the rainbow to stand in protest. There is another instance where a group of Latin American activists created a "hidden flag", with their outfits in Russia which bans the rainbow flag.

Critiques

Concern has been expressed among some of the rainbow symbol being white-washed and regressed to maintain a Eurocentric and colonial influence. A concept called "pride for sale" refers to an overflowing amount of publicity and advertising from big companies displaying the rainbow flag and selling pride merchandise during pride month, but as soon as pride month is over so are all of the promotions. There is also a critique made about how the pride flag has deviated too much from its purpose as a radical symbol for queer rights specifically.

Variations

Many variations of the rainbow flag have been used. Some of the more common ones include the Greek letter lambda (lower case) in white in the middle of the flag and a pink triangle or black triangle in the upper left corner. Other colors have been added, such as a black stripe symbolizing those community members lost to AIDS. The rainbow colors have also often been used in gay alterations of national and regional flags, replacing for example the red and white stripes of the flag of the United States. In 2007, the Pride Family Flag was unveiled at the Houston, Texas pride parade.

In the early years of the AIDS pandemic, activists designed a "Victory over AIDS" flag consisting of the standard six-stripe rainbow flag with a black stripe across the bottom. Leonard Matlovich, himself dying of AIDS-related illness, suggested that upon a cure for AIDS being discovered, the black stripes be removed from the flags and burned.

In 2002, another LGBT activist, Eddie Reynoso recreated Gilbert Baker’s original 1978 tie-dye flag, incorporating a blue canton, with white stars that were painted to a pink color, as residents in states across the nation gained the right to same-gender marriage. The flag- named the Pride Constellation, was first painted on a canvas - as a protest symbol during Nevada’s constitutional amendment to define marriage as that between and man and a women. In 2009, the flag was featured prominently on local and national news outlets as they reported on the California Supreme Court’s ruling- to uphold the state’s marriage equality ban.

Reynoso later rearranged the stars by order of admission into the Union, retaining part of Gilbert Bakers tie-dye flag and the Pride New Glory Flag.

In 2015, Reynoso’s flag once again made national news after it was featured across various news outlets reporting on the Obergefell v. Hodges oral arguments at the Supreme Court.

LGBT communities in other countries have adopted the rainbow flag. A South African gay pride flag which is a hybrid of the rainbow flag and the national flag of South Africa was launched in Cape Town in 2010. Flag designer Eugene Brockman said "I truly believe we (the LGBT community) put the dazzle into our rainbow nation and this flag is a symbol of just that."

In March 2017, Gilbert Baker created a nine-stripe version of his original 1977 flag, with lavender, pink, turquoise and indigo stripes along with the red, orange, yellow, green and violet. According to Baker, the lavender stripe symbolizes diversity.

In June 2017, the city of Philadelphia adopted a revised version of the flag designed by the marketing firm Tierney that adds black and brown stripes to the top of the standard six-color flag, to draw attention to issues of people of color within the LGBT community.

On February 12, 2018, during the street carnival of São Paulo, thousands of people attended a parade called Love Fest, which celebrated human diversity, sexual and gender equality. A version of the flag, created by Estêvão Romane, co-founder of the festival, was unveiled which presented the original eight stripe flag with a white stripe in the middle, representing all colors (human diversity in terms of religion, gender, sex preferences, ethnicities), and peace and union among all.

In June 2018, designer Daniel Quasar released a redesign incorporating elements from both the Philadelphia flag and trans pride flag to bring focus on inclusion and progress within the community. The flag design spread quickly as the Progress Pride Flag on social media, prompting worldwide coverage in news outlets. While retaining the common six-stripe rainbow design as a base, the "Progress" variation adds a chevron along the hoist that features black, brown, light blue, pink, and white stripes to bring those communities (marginalized people of color, trans people, and those living with HIV/AIDS and those who have been lost) to the forefront; "the arrow points to the right to show forward movement, while being along the left edge shows that progress still needs to be made."

In July 2018 the Social Justice Pride Flag was released in Chennai, India in the Chennai Queer LitFest inspired by the other variations of the Pride flag around the world. The flag was designed by Chennai-based gay activist Moulee. The design incorporated elements representing Self-Respect Movement, anti-caste movement and leftist ideology in its design. While retaining the original six stripes of the rainbow flag, the Social Justice Pride Flag incorporates black representing the Self-Respect Movement, blue representing Ambedkarite movement and red representing left values.

In 2018, marchers at the Equality March in Częstochowa carried a modified version of the flag of Poland in rainbow colors. They were reported to prosecutors for desecration of national symbols of Poland, but the prosecutors determined that no crime had been committed.

Also in 2018, Puerto Rican two-spirit designer Julia Feliz designed a variation called the New Pride Flag. According to Feliz, the flag integrates the historic and modern-day struggles of the LGBT movements with racism, following intersectionality. The design adds the colors of the Trans Pride Flag with brown and black diagonal stripes, emphasizing the importance of trans people of color for the queer rights movement from its inception at the Stonewall riots. The flag was first released online in the summer of 2018. Feliz's design was used in the Amsterdam chapter of COC Nederland in the Netherlands; at Washington State University Vancouver during the Transgender Day of Remembrance; by the pride parade in Brighton and Hove, UK; and by Tufts University in the 2019 Boston Pride Parade. According to its website, the design can be used for free for non-commercial purposes and for commercial use by individual transgender and queer Black and Indigenous people. Since 2021, proceeds from the design go to a mutual-aid based US nonprofit aimed at BIPOC transgender and queer people and about spreading awareness on the disproportionate effects of transphobia and homophobia on these people.

In 2021, Valentino Vecchietti of Intersex Equality Rights UK redesigned the Progress Pride Flag to incorporate the intersex flag. This design added a yellow triangle with a purple circle in it to the chevron of the Progress Pride flag. It also changed the color of green to a lighter shade without adding new symbolism. Intersex Equality Rights UK posted the new flag on Instagram and Twitter.

Reception

The reception to new variations and iterations of the Pride Flag have been mixed. Supporters have praised the focus on inclusion, and the highlighting the role and discrimination of people of color in the LGBT community. At the same time, some have expressed concern that the changes only act as a "performance, creating the impression of inclusion without real commitment", or that they have been "for the sake of branding", while not reflecting any actual "material steps towards real equality". Others have remained critical, arguing that the original design already acts as a symbol of unity, and emphasized that the original flag was designed without any racial dimension in mind. Other critics have called the variations "patronizing" and that they have taken away some "universality". Both the Philadelphia Pride Flag and the Progress Pride Flag were met with some controversy and backlash for these reasons, but also praise and widespread adoption.

Notable flag creations

Mile-long flags

For the 25th anniversary of the June 1969 Stonewall Riots in 1994, flag creator Baker, aka Sister Chanel 2001 of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, was commissioned to create the world's largest rainbow flag. The mile-long flag, dubbed "Raise the Rainbow", took months of planning and teams of volunteers to coordinate every aspect. The flag utilized the basic six colors and measured 30 feet (9.1 m) wide. After the march, foot-wide (0.30 m) sections of the flag were given to individual sponsors after the event had ended. Additional large sections of the flag were sent with activists and used in pride parades and LGBT marches worldwide. One large section was later taken to Shanghai Pride in 2014 by a small contingent of San Francisco Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and documented in the film Stilettos for Shanghai. The Guinness Book of World Records confirmed it as the world's largest flag.

In 2003 Baker was again commissioned to produce a giant flag marking the 25th anniversary of the flag itself. Dubbed "25Rainbow Sea to Sea", the project entailed Baker again working with teams of volunteers but this flag utilized the original eight colors and measured one and a quarter miles (2 km) across Key West, Florida, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. The flag was again divided afterwards and sections were sent to over a hundred cities worldwide.

Other large flags

The largest rainbow flag in the Southern Hemisphere is a six-stripe one first flown to mark the fourth Nelson Mandela Bay (NMB) Pride in 2014, held in the Eastern Cape province city of South Africa, Port Elizabeth. It measures twelve by eight metres (39 by 26 ft), and flies on the country's tallest flag pole, which is sixty metres (200 ft) high, and is in Donkin Reserve, in Port Elizabeth's central business district. NMB Pride had the flag manufactured, in part, as a symbol for LGBT youth to feel empowered even if they were not able to come out. On the decision to fly the flag, a spokesperson for the municipality said, NMB "officially adds its voice to governments committing, firstly, to recognizing the LGBT community, and most importantly, to uphold the rights of the LGBT community". It is regularly flown for NMB Pride as well as March 21 which is Human Rights Day in South Africa, and International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, both commemorating the 1960 Sharpeville massacre.

On June 1, 2018, Venice Pride in California flew the world's largest free-flying flag to launch United We Pride. After its debut for Venice Pride, the flag traveled to San Francisco at the end of the month for SF Pride and the fortieth anniversary of the rainbow flag's adoption. United We Pride then had the flag sent to Paris, London, Berlin, Vancouver, Sydney, Miami, and Tokyo, ending in New York City for Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019. The giant flag was produced by the flag originator Gilbert Baker, and measures 131 square metres (1,410 sq ft).

In June 2019, to coincide with the fifty-year anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, steps at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park were turned into the largest LGBT pride flag. The rainbow-decorated 12-by-100-foot (3.7 m × 30.5 m) staircase Ascend With Pride was installed June 14–30.

Influence

Additional pride flags

The popularity of the rainbow flag has influenced the creation and adoption of a wide variety of multi-color multi-striped flags used to communicate specific identities within the LGBT community, including the bisexual pride flag, pansexual pride flag, and transgender pride flags.

Spirit Day

Spirit Day, an annual LGBT awareness day since 2010, takes its name from the violet stripe representing "spirit" on the rainbow flag. Participants wear purple to show support for LGBT youth who are victims of bullying.