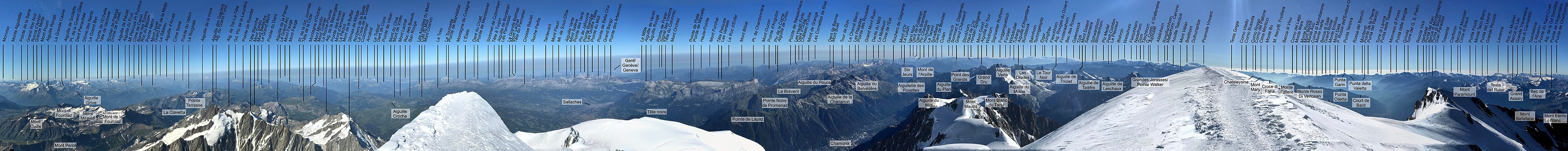

Summit of Mont Blanc and the Bosses ridge | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 4,807.81 m (15,773.7 ft) |

| Prominence | 4696 m ↓ by Lake Kubenskoye Ranked 11th |

| Parent peak | Mount Everest[note 1] |

| Isolation | 2,812 km → Kukurtlu Dome |

| Listing | Country high point Ultra Seven Summits |

| Coordinates | 45°50′0″N 6°52′2″ECoordinates: 45°50′0″N 6°52′2″E |

| Geography | |

| Location | Aosta Valley, Italy Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France |

| Countries | France and Italy |

| Parent range | Graian Alps |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 8 August 1786 by |

Mont Blanc (French: Mont Blanc [mɔ̃ blɑ̃]; Italian: Monte Bianco [ˈmonte ˈbjaŋko], both meaning "white mountain") is the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe, rising 4,807.81 m (15,774 ft) above sea level. It is the second-most prominent mountain in Europe, after Mount Elbrus, and it is the eleventh most prominent mountain summit in the world.

It gives its name to the Mont Blanc massif which straddles parts of France, Italy and Switzerland. Mont Blanc's summit lies on the watershed line between the valleys of Ferret and Veny in Italy, and the valleys of Montjoie, and Arve in France. Ownership of the summit area has long been a subject of dispute between France and Italy.

The Mont Blanc massif is popular for outdoor activities like hiking, climbing, trail running and winter sports like skiing, and snowboarding. The most popular climbing route to the summit of Mont Blanc is the Goûter Route, which typically takes two days.

The three towns and their communes which surround Mont Blanc are Courmayeur in Aosta Valley, Italy; and Saint-Gervais-les-Bains and Chamonix in Haute-Savoie, France. The latter town was the site of the first Winter Olympics. A cable car ascends and crosses the mountain range from Courmayeur to Chamonix, through the Col du Géant. The 11.6 km (7+1⁄4-mile) Mont Blanc Tunnel, constructed between 1957 and 1965, runs beneath the mountain and is a major transalpine transport route.

Geology

Mont Blanc and adjacent mountains in the massif are predominately formed from a large intrusion of granite (termed a batholith) which was forced up through a basement layer of gneiss and mica schists during the Variscan mountain-forming event of the late Palaeozoic period. The summit of Mont Blanc is located at the point of contact of these two rock types. To the south west, the granite contact is of a more intrusive nature, whereas to the north east it changes to being more tectonic. The granites are mostly very-coarse grained, ranging in type from microgranites to porphyroid granites. The massif is tilted in a north-westerly direction and was cut by near-vertical recurrent faults lying in a north–south direction during the Variscan orogeny. Further faulting with shear zones subsequently occurred during the later Alpine orogeny. Repeated tectonic phases have caused breakup of the rock in multiple directions and in overlapping planes. Finally, past and current glaciation caused significant sculpting of the landscape into its present-day form.

The first systematic account of the minerals of the Mont Blanc area was published in 1873 by Venance Payot. His list, entitled "Statistique minéralogique des environs du Mt-Blanc", catalogued 90 mineral types although it also included those present only as very small components of rocks. If these are excluded, it is known today that at least 68 separate mineral species occur across the wider range of the Mont Blanc massif.

Climate

Located on the watershed between the Rhône and the Po, the massif of Mont Blanc is also situated between the two different climatic regions of the northern and western Alps, and that of the southern Alps. Climatic conditions on the Mer de Glace are similar to those found on the northern side of the Swiss Alps.

The climate is cold and temperate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), and is greatly influenced by altitude. Being the highest part of the Alps, Mont Blanc and surrounding mountains can create their own weather patterns. Temperatures drop as the mountains gain in height, and the summit of Mont Blanc is a permanent ice cap, with temperatures around −20 °C (−4 °F). The summit is also prone to strong winds and sudden weather changes. Because of its great overall height, a considerable proportion is permanently glaciated or snow-covered and is exposed to extremely cold conditions.

There is, however, significant variation in precipitation with altitude. For example, the village of Chamonix below Mont Blanc is at an elevation of approximately 1,030 metres (3,380 ft) and receives around 1,020 mm (40 in) of annual precipitation, whilst the Col du Midi, which is at 3,500 metres (11,500 ft) above sea level, receives significantly more, totalling 3,100 mm (122 in). However, at an even higher altitude (near to the summit of Mont Blanc) precipitation is considerably less, with only around 1,100 mm (43 in) recorded, despite the latter measurements being taken at a height of 4,300 metres (14,100 ft).

History

Since 1760 Swiss naturalist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure began to go to Chamonix to observe Mont Blanc. He tried with the Courmayeur mountain guide Jean-Laurent Jordaney, a native of Pré-Saint-Didier, who accompanied De Saussure since 1774 on the Miage Glacier and on Mont Crammont.

The first recorded ascent of Mont Blanc (at the time neither within Italy nor France) was on 8 August 1786 by Jacques Balmat and the doctor Michel Paccard. This climb, initiated by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, who gave a reward for the successful ascent, traditionally marks the start of modern mountaineering. The first woman to reach the summit was Marie Paradis in 1808.

Ownership of the summit

At the scale of the Mont Blanc massif, the border between Italy and France passes along most of the main Alpine watershed, from the Aiguille des Glaciers to Mont Dolent, where it reaches the border with Switzerland. However, its precise location near the summits of Mont Blanc and nearby Dôme du Goûter has been disputed since the 18th century. Italian officials claim the border follows the watershed, splitting both summits between Italy and France, while French officials claim the border avoids the two summits, placing both of them entirely with France. The size of these two (distinct) disputed areas is approximately 65 ha on Mont Blanc and 10 ha on Dôme du Goûter.

Since the French Revolution, the issue of the ownership of the summit has been debated. From 1416 to 1792, the entire mountain was within the Duchy of Savoy. In 1723, the Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus II, acquired the Kingdom of Sardinia. The resulting state of Sardinia was to become preeminent in the Italian unification. In September 1792, the French Revolutionary Army of the Alps under Anne-Pierre de Montesquiou-Fézensac seized Savoy without much resistance and created a department of the Mont Blanc. In a treaty of 15 May 1796, Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia was forced to cede Savoy and Nice to France. In article 4 of this treaty, it says: "The border between the Sardinian kingdom and the departments of the French Republic will be established on a line determined by the most advanced points on the Piedmont side, of the summits, peaks of mountains and other locations subsequently mentioned, as well as the intermediary peaks, knowing: starting from the point where the borders of Faucigny, the Duchy of Aoust and the Valais, to the extremity of the glaciers or Monts-Maudits: first the peaks or plateaus of the Alps, to the rising edge of the Col-Mayor". This act further states that the border should be visible from the town of Chamonix and Courmayeur. However, neither is the peak of the Mont Blanc visible from Courmayeur nor is the peak of the Mont Blanc de Courmayeur visible from Chamonix because part of the mountains lower down obscure them.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Congress of Vienna restored the King of Sardinia in Savoy, Nice, and Piedmont, his traditional territories, overruling the 1796 Treaty of Paris. Forty-five years later, after the Second Italian War of Independence, it was replaced by a new legal act. This act was signed in Turin on 24 March 1860 by Napoleon III and Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, and deals with the annexation of Savoy (following the French neutrality for the plebiscites held in Tuscany, Modena, Parma and Romagna to join the Kingdom of Sardinia, against the Pope's will). A demarcation agreement, signed on 7 March 1861, defined the new border. With the formation of Italy, for the first time Mont Blanc was located on the border of France and Italy, along the old border on the watershed between the department of Savoy and that of Piedmont formerly belonging to the Kingdom of Savoy.

The 1860 act and attached maps are still legally valid for both the French and Italian governments. In the second half of the nineteenth century, on surveys carried out by a cartographer of the French army, Captain JJ Mieulet, a topographic map was published in France, which incorporated the summit into French territory, making the state border deviate from the watershed line, and giving rise to the differences with the maps published in Italy in the same period.

Modern Swiss mapping, published by the Federal Office of Topography, plots a region of disputed territory (statut de territoire contesté) around the summits of both Mont Blanc and the Dôme du Goûter. One of its interpretations of the French-Italian border places both summits straddling a line running directly along the geographic ridgeline (watershed) between France and Italy, thus sharing their summits equally between both states. However, a second interpretation places both summits, as well as that of Mont Blanc de Courmayeur (although much less clearly in the latter case), solely within France.

NATO maps take data from the Italian national mapping agency, the Istituto Geografico Militare, which is based upon past treaties in force.

As of 2021, the border dispute between the two countries is ongoing.

1832

Map of the Kingdom of Sardinia showing an administrative border passing

through the summit of Mont Blanc. This was the same map annexed to the

1860 treaty to determine the current border between France and Italy. |

Captain Mieulet map of 1865 placing the international border south of the watershed |

A Sardinian Atlas map of 1869 showing the international border on the watershed. |

1:50'000 Swiss National Map, with both disputed areas marked

|

Vallot

The first professional scientific investigations on the summit were conducted by the botanist–meteorologist Joseph Vallot at the end of the 19th century. He wanted to stay near the top of the summit to undertake detailed research, so he built his permanent cabin.

Janssen observatory

In 1890, Pierre Janssen, an astronomer and the director of the Meudon astrophysical observatory, considered the construction of an observatory at the summit of Mont Blanc. Gustave Eiffel agreed to take on the project, provided he could build on a rock foundation, if found at a depth of less than 12 m (39 ft) below the ice. In 1891, the Swiss surveyor Imfeld dug two 23-metre-long (75 ft) horizontal tunnels 12 metres (39 ft) below the ice summit but found nothing solid. Consequently, the Eiffel project was abandoned.

Despite this, the observatory was built in 1893. During the cold wave of January 1893, a temperature of −43 °C (−45 °F) was recorded on Mont Blanc, being the lowest ever recorded there.

Levers attached to the ice supported the observatory. This worked to some extent until 1906 when the building started leaning heavily. The movement of the levers corrected the lean slightly, but three years later (two years after Janssen's death), a crevasse started opening under the observatory. It was abandoned. Eventually the building fell, and only the tower could be saved in extremis.

Air crashes

The mountain was the scene of two fatal air crashes; Air India Flight 245 in 1950 and Air India Flight 101 in 1966. Both planes were approaching Geneva Airport and the pilots miscalculated their descent; 48 and 117 people, respectively, died. The latter passengers included nuclear scientist Homi J. Bhabha, known as the "father" of India's nuclear programme.

Tunnel

In 1946, a drilling project was initiated to carve a tunnel through the mountain. The Mont Blanc tunnel would connect Chamonix, France, and Courmayeur, Italy, and become one of the major transalpine transport routes between the two countries. In 1965, the tunnel opened to vehicle traffic with a length of 11,611 metres (7.215 mi).

1999 disaster

In 1999, a transport truck caught fire in the tunnel beneath the mountain. In total 39 people were killed when the fire raged out of control. The tunnel was renovated in the aftermath to increase driver safety. Renovations include computerised detection equipment, extra security bays, a parallel escape shaft, and a fire station in the middle of the tunnel. The escape shafts also have clean air flowing through them via vents. Any people in the security bays now have live video contact to communicate with the control centre. A remote site for cargo safety inspection was created on each side: Aosta in Italy and Passy-Le Fayet in France. Here all trucks are inspected before entering the tunnel. These remote sites are also used as staging areas to control commercial traffic during peak hours. The renovated tunnel reopened three years after the disaster.

Elevation

The summit of Mont Blanc is a thick, perennial ice-and-snow dome whose thickness varies. No exact and permanent summit elevation can therefore be determined, though accurate measurements have been made on specific dates. For a long time, its official elevation was 4,807 m (15,771 ft). In 2002, the IGN and expert surveyors, with the aid of GPS technology, measured it to be 4,807.40 m (15,772 ft 4 in).

After the 2003 heatwave in Europe, a team of scientists remeasured the height on 6 and 7 September. The team was made up of the glaciologist Luc Moreau, two surveyors from the GPS Company, three people from the IGN, seven expert surveyors, four mountain guides from Chamonix and Saint-Gervais and four students from various institutes in France. This team noted that the elevation was 4,808.45 m (15,775 ft 9 in), and the peak was 75 cm (30 in) away from where it had been in 2002.

After these results were published, more than 500 points were measured to assess the effects of climate change and the fluctuations in the height of the mountain at different points. Since then, the elevation of the mountain has been measured every two years.

The summit was measured again in 2005, and the results were published on 16 December 2005. The height was found to be 4,808.75 m (15,776 ft 9 in), 30 cm (12 in) more than the previous recorded height. The rock summit was found to be at 4,792 m (15,722 ft), some 40 m (130 ft) west of the ice-covered summit.

In 2007, the summit was measured at 4,807.9 m (15,774 ft) and in 2009 at 4,807.45 m (15,772 ft). In 2013, the summit was measured at 4,810.02 m (15,781 ft) and in 2015 at 4,808.73 m (15,777 ft). From the summit of Mont Blanc on a clear day, the Jura, the Vosges, the Black Forest and the Massif Central mountain ranges can be seen, as well as the principal summits of the Alps.

Climbing routes

Several classic climbing routes lead to the summit of Mont Blanc:

- The most popular route is the Goûter Route, also known as the Voie Des Cristalliers or the Voie Royale. Starting from Saint-Gervais-les-Bains, the Tramway du Mont-Blanc (TMB) is taken to get to the Gare du Nid d'Aigle. The ascent begins in the direction of the Refuge de Tête Rousse, crossing the Grand Couloir or Goûter Corridor, considered dangerous because of frequent rockfalls, leading to the Goûter Hut for night shelter. The next day the route leads to the Dôme du Goûter, past the emergency Vallot cabin and L'arrête des Bosses.

- La Voie des 3 Monts is also known as La Traversée. Starting from Chamonix, the Téléphérique de l'Aiguille du Midi is taken towards the Col du Midi. The Cosmiques Hut is used to spend the night. The next day the ascent continues over Mont Blanc du Tacul and Mont Maudit.

- The historic itinerary via the Grands Mulets Hut, or old normal route on the French side, which is most frequently traversed in winter by ski, or in summer to descend to Chamonix.

- The normal Italian itinerary is also known as La route des Aiguilles Grises. After crossing the Miage Glacier, climbers spend the night at the Gonella refuge. The next day, one proceeds through the Col des Aiguilles Grises and the Dôme du Goûter, concluding at L'arête des Bosses (Bosses ridge).

- The Miage – Bionnassay – Mont Blanc crossing is usually done in three days, and has been described as a truly magical expedition of ice and snow arêtes at great altitude.[36]: 199 The route begins from Contamines-Montjoie, with the night spent in the Conscrits Hut. The following day, the Dômes de Miages is crossed and the night is spent at the Durier cabin. The third day proceeds over l'Aiguille de Bionnassay and the Dôme du Goûter, finally reaching the summit of Mont Blanc via the Bosses ridge.

Nowadays the summit is ascended by an average of 20,000 mountaineer tourists each year. It could be considered a technically easy, yet arduous ascent for someone well-trained and acclimatised to the altitude. From l'Aiguille du Midi (where the cable car stops), Mont Blanc seems quite close, being 1,000 m (3,300 ft) higher. But while the peak seems deceptively close, the La Voie des 3 Monts route (known to be more technical and challenging than other more commonly used routes) requires more ascent over two other 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) mountains, Mont Blanc du Tacul and Mont Maudit, before the final section of the climb is reached and the last 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) push to the summit is undertaken.

Each year climbing deaths occur on Mont Blanc, and on the busiest weekends, normally around August, the local rescue service performs an average of 12 missions, mostly directed to aid people in trouble on one of the normal routes of the mountain. Some routes require knowledge of high-altitude mountaineering, a guide (or at least an experienced mountaineer), and all require proper equipment. All routes are long and arduous, involving delicate passages and the hazard of rockfall or avalanche. Climbers may also suffer altitude sickness, occasionally life-threatening, particularly if they are not properly acclimatised.

Fatalities

A 1994 estimate suggests there had been 6,000 to 8,000 alpinist fatalities in total, more than on any other mountain. These numbers exclude the fatalities of Air India Flight 245 and Air India Flight 101, two planes that crashed into Mont Blanc. Despite unsubstantiated claims recurring in media that "some estimates put the fatality rate at an average of 100 hikers a year", actual reported annual numbers at least since the 1990s are between 10 and 20: in 2017, fourteen people died out of 20,000 summit attempts and two remained missing; with 15 in 2018 as of August.

A French study on the especially risky "Goûter couloir, on the normal route on Mont Blanc" and necessary rescue operations found that, between 1990 and 2011, there were 74 deaths "between the Tête Rousse refuge (3,187 m) and the Goûter refuge (3,830 m)". There were 17 more in 2012–15, none in 2016, and 11 in 2017.

Refuges

- Refuge Vallot, 4362 m

- Bivouac Giuseppe Lampugnani, 3860 m

- Bivouac Marco Crippa, 3840 m

- Refuge Goûter, 3817 m

- Bivouac Corrado Alberico – Luigi Borgna, 3684 m

- Refuge Cosmiques, 3613 m

- Refuge Tête Rousse, 3167 m

- Refuge Francesco Gonella, 3071 m

- Refuge Grands Mulets, 3050 m

Impacts of climate change

Recent temperature rises and heatwaves, such as those of the summers of 2015 and 2018, have had significant impacts on many climbing routes across the Alps, including those on Mont Blanc. For example, in 2015, the Grand Mulets route, previously popular in the 20th century, was blocked by virtually impenetrable crevasse fields, and the Gouter Hut was closed by municipal decree for some days because of a very high rockfall danger, with some stranded climbers evacuated by helicopter.

In 2016 a crevasse opened at high altitude, also indicating previously unobserved glacial movements. The new crevasse forms an obstacle to be scaled by climbing parties on the final part of the itinerary to the top shared by the popular Goûter Route and the Grand Mulets Route.

Exploits and incidents

- 1786: The first ascent, by Michel-Gabriel Paccard and Jacques Balmat; see Exploration of the High Alps.

- 1787: The fourth ascent, by Englishman Mark Beaufoy, with at least six guides and a servant.

- July 1808: The first ascent by a woman, Maria Paradis, with Balmat as her guide.

- July 1838: The second ascent by a woman, Henriette d'Angeville.

- 1890: Giovanni Bonin, Luigi Grasselli and Fr. Achille Ratti (later Pope Pius XI) discovered the normal Italian route (West Face Direct) on descent.

- 1950: Air India Flight 245 crashes into Mont Blanc.

- 1966: Air India Flight 101 crashes into Mont Blanc.

- 1960: The airplane pilot Henri Giraud landed on the summit, which is only 30 m (98 ft) long.

- 1990: The Swiss Pierre-André Gobet, leaving from Chamonix, completed the ascent and descent in 5 hours, 10 minutes and 14 seconds.

- 30 May 2003: Stéphane Brosse and Pierre Gignoux tried to beat the record by ski-walking. They went up in 4 hours and 7 minutes and came back down in 1 hour and 8 minutes. In total, they did the ascent and descent in 5 hours and 15 minutes.

- 13 August 2003: Seven French paraglider pilots landed on the summit. They reached a peak altitude of 5,200 m (17,100 ft), thanks to the hot weather conditions, which provided strong hot air currents. Five had left from Planpraz, one from Rochebrune at Megève and the last one from Samoëns.

- 8 June 2007: Danish artist Marco Evaristti draped the peak of Mont Blanc with red fabric, along with a 20-foot (6.1 m) pole with a flag reading "Pink State". He had been arrested and detained earlier on 6 June for attempting to paint a pass leading up to the summit red. He aimed to raise awareness of environmental degradation.

- 13 September 2007: A group of 20 people set up a hot tub at the summit.

- 19 August 2012: Fifty paraglider pilots landed on the summit, beating the previous record of seven top landing pilots, set in 2003. This included the second ever tandem landing on the summit.

- 11 July 2013: Kilian Jornet beat the fastest overall time for ascent and descent with 4 hours 57 minutes and 40 seconds.

- 21 June 2018: Emelie Forsberg set a women's fastest known time up and down from Chamonix with 7 hours 53 minutes and 12 seconds, improving her previous record of 8 hours 10 minutes from 2013.

Incidents involving children

In July 2014, an American entrepreneur and traveller Patrick Sweeney attempted to break the record with his nine-year-old son and 11-year-old daughter. They were caught in an avalanche, escaped death and decided not to pursue their attempt.

In August 2014, an unknown Austrian climber with his 5-year-old son were intercepted by mountain gendarmes at 3,200 metres (10,500 ft) and forced to turn back.

On 5 August 2017, 9-year-old Hungarian twins and their mother were rescued from 3,800 metres (12,500 ft) by helicopter while their father and family friend continued their summit attempt.

Cultural references

Cinema and television

- La Terre, son visage, is a documentary by Jean-Luc Prévost and published by Édition Société national de télévision française, released in 1984. It is part of the Haroun Tazieff raconte sa terre, vol. 1 series. In it he talks about the west–east crossing of Mont Blanc.

- The film Malabar Princess.

- The television-film Premier de cordée.

- Storm over Mont Blanc (Stürme über dem Mont Blanc, 1930) with Leni Riefenstahl and directed by Arnold Fanck

- La Roue (The Wheel, 1923) is a 273-minute film by Abel Gance depicting rail operations, workers, and families in south-eastern France, including the Mont Blanc area.

Literature

- Premier de cordée by Roger Frison-Roche

- Hugo et le Mont Blanc by Colette Cosnie – Édition Guérin

- Hymn Before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Manfred by Lord Byron

- Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley

- Mont Blanc by Percy Shelley

- Point Blanc by Anthony Horowitz

- The Prelude Book VI by William Wordsworth

Mont Blanc., by Letitia Elizabeth Landon, a poem to accompany an engraving of a painting by J. M. W. Turner.

Mont Blanc., by Letitia Elizabeth Landon, a poem to accompany an engraving of a painting by J. M. W. Turner.- Kordian by Juliusz Słowacki

- Eiger Dreams: Ventures Among Men and Mountains by Jon Krakauer

- Running Water by AEW Mason

- La neige en deuil by Henri Troyat

Protection

The Mont Blanc massif is being put forward as a potential World Heritage Site because of its uniqueness and its cultural importance, considered the birthplace and symbol of modern mountaineering. It would require the three governments of Italy, France and Switzerland to request UNESCO for it to be listed.

Mont Blanc is one of the most visited tourist destinations in the world, and for this reason, some view it as threatened. Pro-Mont Blanc (an international collective of associations for the protection of Mont Blanc) published in 2002 the book Le versant noir du mont Blanc (The black hillside of Mont Blanc), which exposes current and future problems in conserving the site.

In 2007, Europe's two highest toilets (at a height of 4,260 metres, 13,976 feet) were taken by helicopter to the top of Mont Blanc. They are also serviced by helicopter. They will serve 30,000 skiers and hikers annually, helping to alleviate the discharge of urine and faeces that spreads down the mountain face with the spring thaw, and turns it into 'Mont Marron'.

Global warming has begun to melt glaciers and cause avalanches on Mont Blanc, creating more dangerous climbing conditions.

Panorama

(view as a 360° interactive panorama)