From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Centre in Australia

suggests that "anti-Americanism" cannot be isolated as a consistent

phenomenon, since the term originated as a rough composite of stereotypes, prejudices,

and criticisms which evolved into more politically-based criticisms.

French scholar Marie-France Toinet says that use of the term

"anti-Americanism" is "only fully justified if it implies systematic

opposition – a sort of allergic reaction – to America as a whole." Scholars such as Noam Chomsky and Nancy Snow

have argued that the application of the term "anti-American" to other

countries or their populations is nonsensical, as it implies that

disliking the American government or its policies is socially

undesirable or even comparable to a crime. In this regard, the term has been likened to the propagandistic usage of the term "anti-Sovietism" in the USSR.

Discussions on anti-Americanism have in most cases lacked a

precise explanation of what the sentiment entails (other than a general

disfavor), which has led the term to be used broadly and in an

impressionistic manner, resulting in the inexact impressions of the many

expressions described as anti-American. Author and expatriate William Russell Melton argues that criticism largely originates from the perception that the U.S. wants to act as a "world policeman".

Negative or critical views of the United States or its influence have been widespread in Russia, China, Serbia, Pakistan, Bosnia, Belarus and the Greater Middle East, but remain low in Israel, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines and certain countries in central and eastern Europe.

Anti-Americanism has also been identified with the term Americanophobia, which Merriam-Webster defines as "hatred of the U.S. or American culture".

Etymology

In the online Oxford Dictionaries the term "anti-Americanism" is defined as "Hostility to the interests of the United States".

In the first edition of Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language

(1828) the term "anti-American" was defined as "opposed to America, or

to the true interests or government of the United States; opposed to the

revolution in America".

In France the use of the noun form antiaméricanisme has been cataloged from 1948, entering ordinary political language in the 1950s.

Rationale

Bradley Bowman, a former professor at the United States Military Academy,

argues that United States military facilities oversea and the forces

stationed there serve as a "major catalyst for anti-Americanism and

radicalization." Other studies have found a link between the presence of

the US bases and al-Qaeda

recruitment. These bases are often cited by opponents of repressive

governments to provoke anger, protest, and nationalistic fervor against

the ruling class and the United States. This in turn, according to JoAnn

Chirico, raises concerns in Washington that a democratic transition

could lead to the closure of bases, which often encourages the United

States to extend its support for authoritarian leaders. This study

suggests that the outcome could be an intensifying cycle of protest and

repression supported by the United States. In 1958, Eisenhower

discussed with his staff what he described as a "campaign of hatred

against us" in the Arab world, "not by the governments but by the

people." The United States National Security Council,

concluded that was due to a perception that the U.S. supports corrupt

and brutal governments and opposes political and economic development

"to protect its interest in Near East oil".

The Wall Street Journal reached a similar conclusion after surveying the views of wealthy and Western Muslims after September 11 attacks.

In this vein, the head of the Council of Foreign Relations terrorism program believes that the American support for repressive regimes such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia is undoubtedly a major factor in anti-American sentiment in the Arab world.

Interpretations

In a poll conducted in 2017 by the BBC World Service of 19 countries, four of the countries rated U.S. influence positively, while 14 leaned negatively, and one was divided.

Anti-Americanism has risen in recent years in Canada, Latin

America, the Middle East, and the European Union, due in part to the

strong worldwide unpopularity of the policies of the Donald Trump administration, though it continues to be low in certain countries in central and eastern Europe[27] Following the 2020 United States presidential election of Joe Biden, global views of the United States have returned to being positive overall once more.[28]

Interpretations of anti-Americanism have often been polarized.

Anti-Americanism has been described by Hungarian-born American

sociologist Paul Hollander as "a relentless critical impulse toward American social, economic, and political institutions, traditions, and values".

German newspaper publisher and political scientist Josef Joffe suggests five classic aspects of the phenomenon: reducing Americans to stereotypes,

believing the United States to have an irredeemably evil nature,

ascribing to the U.S. establishment a vast conspiratorial power aimed at

utterly dominating the globe,

holding the U.S. responsible for all the evils in the world, and

seeking to limit the influence of the U.S. by destroying it or by

cutting oneself and one's society off from its polluting products and

practices. Other advocates of the significance of the term argue that anti-Americanism represents a coherent and dangerous ideological current, comparable to anti-Semitism. Anti-Americanism has also been described as an attempt to frame the consequences of U.S. foreign policy

choices as evidence of a specifically American moral failure, as

opposed to what may be unavoidable failures of a complicated foreign

policy that comes with superpower status.

Its status as an "-ism"

is a greatly contended suspect, however. Brendon O'Connor notes that

studies of the topic have been "patchy and impressionistic," and often

one-sided attacks on anti-Americanism as an irrational position. American academic Noam Chomsky,

a prolific critic of the U.S. and its policies, asserts that the use of

the term within the U.S. has parallels with methods employed by totalitarian states or military dictatorships; he compares the term to "anti-Sovietism", a label used by the Kremlin to suppress dissident or critical thought, for instance.

The concept "anti-American" is an

interesting one. The counterpart is used only in totalitarian states or

military dictatorships... Thus, in the old Soviet Union, dissidents were

condemned as "anti-Soviet". That's a natural usage among people with

deeply rooted totalitarian instincts, which identify state policy with

the society, the people, the culture. In contrast, people with even the

slightest concept of democracy treat such notions with ridicule and

contempt.

Some have attempted to recognize both positions. French academic

Pierre Guerlain has argued that the term represents two very different

tendencies: "One systematic or essentialist, which is a form of

prejudice targeting all Americans. The other refers to the way

criticisms of the United States are labeled 'anti-American' by

supporters of U.S. policies in an ideological bid to discredit their

opponents".

Guerlain argues that these two "ideal types" of anti-Americanism can

sometimes merge, thus making discussion of the phenomenon particularly

difficult. Other scholars have suggested that a plural of

anti-Americanisms, specific to country and time period, more accurately

describe the phenomenon than any broad generalization. The widely used "anti-American sentiment", meanwhile, less explicitly implies an ideology or belief system.

Globally, increases in perceived anti-American attitudes appear to correlate with particular policies or actions, such as the Vietnam and Iraq

wars. For this reason, critics sometimes argue the label is a

propaganda term that is used to dismiss any censure of the United States

as irrational.

American historian Max Paul Friedman has written that throughout

American history the term has been misused to stifle domestic dissent

and delegitimize any foreign criticism.

According to an analysis by German historian Darius Harwardt, the term

is nowadays mostly used to stifle debate by attempting to discredit

viewpoints that oppose American policies.

History

18th and 19th centuries

Degeneracy thesis

In the mid- to late-eighteenth century, a theory emerged among some

European intellectuals which stated that the landmasses of the New World

were inherently inferior to that of Europe. Proponents of the so-called

"degeneracy thesis" held the view that climatic extremes, humidity and

other atmospheric conditions in America physically weakened both men and

animals.

American author James W. Ceaser and French author Philippe Roger have

interpreted this theory as "a kind of prehistory of anti-Americanism"

and have (in the words of Philippe Roger) been a historical "constant"

since the 18th century, or again an endlessly repetitive "semantic

block". Others, like Jean-François Revel, have examined what lay hidden behind this 'fashionable' ideology. Purported evidence for the idea included the smallness of American fauna, dogs that ceased to bark, and venomous plants; one theory put forth was that the New World had emerged from the Biblical flood later than the Old World. Native Americans were also held to be feeble, small, and without ardor.

The theory was originally proposed by Comte de Buffon, a leading French naturalist, in his Histoire Naturelle (1766). The French writer Voltaire joined Buffon and others in making the argument. Dutchman Cornelius de Pauw, court philosopher to Frederick II of Prussia became its leading proponent. While Buffon focused on the American biological environment, de Pauw attacked the people who were native to the continent.

James Ceaser has noted that the denunciation of America as inferior to

Europe was partially motivated by the German government's fear of mass emigration;

de Pauw was called upon to convince the Germans that the new world was

inferior. De Pauw is also known to have influenced the philosopher Immanuel Kant in a similar direction.

De Pauw said that the New World was unfit for human habitation

because it was, "so ill-favored by nature that all it contains is either

degenerate or monstrous". He asserted that, "the earth, full of

putrefaction, was flooded with lizards, snakes, serpents, reptiles and

insects". Taking a long-term perspective, he announced that he was,

"certain that the conquest of the New World...has been the greatest of

all misfortunes to befall mankind."

The theory made it easier for its proponents to argue that the

natural environment of the United States would prevent it from ever

producing a true culture. Echoing de Pauw, the French Encyclopedist Abbé Raynal

wrote in 1770, "America has not yet produced a good poet, an able

mathematician, one man of genius in a single art or a single science". The theory was debated and rejected by early American thinkers such as Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson; Jefferson, in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), provided a detailed rebuttal of de Buffon from a scientific point of view. Hamilton also vigorously rebuked the idea in Federalist No. 11 (1787).

One critic, citing Raynal's ideas, suggests that it was specifically extended to the Thirteen Colonies that would become the United States.

Roger suggests that the idea of degeneracy posited a symbolic, as

well as a scientific, America that would evolve beyond the original

thesis. He argues that Buffon's ideas formed the root of a

"stratification of negative discourses" that has recurred throughout the

history of the two countries' relationship (and been matched by

persistent Francophobia in the United States).

Culture

According to Brendan O'Connor, some Europeans criticized Americans

for lacking "taste, grace and civility," and having a brazen and

arrogant character. British author Frances Trollope observed in her 1832 book Domestic Manners of the Americans, that the greatest difference between the English and Americans

was "want of refinement", explaining: "that polish[,] which removes the

coarser and rougher parts of our nature[,] is unknown and undreamed of"

in America.

According to one source, her account "succeeded in angering Americans

more than any book written by a foreign observer before or since". English writer Captain Marryat's critical account in his Diary in America, with Remarks on Its Institutions (1839) also proved controversial, especially in Detroit where an effigy of the author, along with his books, was burned. Other writers critical of American culture and manners included the bishop Talleyrand in France and Charles Dickens in England. Dickens' novel Martin Chuzzlewit (1844) is a ferocious satire on American life.

Simon Schama observed in 2003: "By the end of the nineteenth century, the stereotype of the ugly American – voracious, preachy, mercenary, and bombastically chauvinist – was firmly in place in Europe".

O'Connor suggests that such prejudices were rooted in an idealized

image of European refinement and that the notion of high European

culture pitted against American vulgarity has not disappeared.

Politics and ideology

The young United States also faced criticism on political and ideological grounds. Ceaser argues that the Romantic strain of European thought and literature, hostile to the Enlightenment view of reason and obsessed with history and national character, disdained the rationalistic American project. The German poet Nikolaus Lenau commented: "With the expression Bodenlosigkeit

(absence of ground), I think I am able to indicate the general

character of all American institutions; what we call Fatherland is here

only a property insurance scheme". Ceaser argues in his essay that such

comments often repurposed the language of degeneracy, and the prejudice

came to focus solely on the United States and not Canada nor Mexico. Lenau had immigrated

to the United States in 1833 and found that the country did not live up

to his ideals, leading him to return to Germany the following year. His

experiences in the U.S. were the subject of a novel titled The America-exhaustion (Der Amerika-Müde) (1855) by fellow German Ferdinand Kürnberger.

The nature of American democracy

was also questioned. The sentiment was that the country lacked "[a]

monarch, aristocracy, strong traditions, official religion, or rigid

class system," according to Judy Rubin, and its democracy was attacked

by some Europeans in the early nineteenth century as degraded, a

travesty, and a failure. The French Revolution,

which was loathed by many European conservatives, also implicated the

United States and the idea of creating a constitution on abstract and

universal principles. That the country was intended to be a bastion of liberty was also seen as fraudulent given that it had been established with slavery. "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?" asked Samuel Johnson in 1775. He famously stated, that "I am willing to love all mankind, except an American".

20th century

Intellectuals

Protest march against the

Vietnam War in Stockholm, Sweden, 1965

Sigmund Freud was vehemently anti-American. Historian Peter Gay

says that in "slashing away at Americans wholesale; quite

indiscriminately, with imaginative ferocity, Freud was ventilating some

inner need". Gay suggests that Freud's anti-Americanism was not really

about the United States at all.

Numerous authors went on the attack. French writer Louis-Ferdinand Celine denounced the United States. German poet Rainer Marie Rilke wrote, "I no longer love Paris, partly because it is disfiguring and Americanizing itself".

Communist critiques

Until its demise in 1991, the Soviet Union and other communist nations emphasized capitalism as the great enemy of communism,

and identified the United States as the leader of capitalism. They

sponsored anti-Americanism among followers and sympathizers. Russell A.

Berman notes that in the mid-19th century, "Marx

himself largely admired the dynamism of American capitalism and

democracy and did not participate in the anti-Americanism that came to

be the hallmark of Communist ideology in the twentieth century".

O'Connor argues that, "communism represented the starkest version of

anti-Americanism – a coherent world view that challenged the free market, private property, limited government, and individualism".

The USA was and is heavily criticised by contemporary socialist nations and movements for imperialism, especially as a reaction to United States involvement in regime change. In the DPRK for example, Anti-Americanism comes not only from ideological opposition to the USA and its actions, but also as a result of allegations of biological warfare in the Korean War and bombing of North Korea.

Authors in the West, such as Bertolt Brecht and Jean-Paul Sartre criticized the U.S. and reached a large audience, especially on the left. In his Anti-Americanism (2003), French writer Jean François Revel argues that anti-Americanism emerges primarily from anti-capitalism, and this critique also comes from non-communist, totalitarian regimes.

America was criticised and denounced by Communists such as Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev during the Russian Civil War, on the grounds of it being a settler state. Galiev particularly emphasised native genocide of America and the institution of slavery.

American treatment of minority groups such as natives and

African-Americans would go on to be a continued point of opposition and

criticism to the USA throughout the 20th century.

The East German

regime imposed an official anti-American ideology that was reflected in

all its media and all the schools. Anyone who expressed support for the

west would be investigated by the Stasi. The official line followed Lenin's theory of imperialism as the highest and last stage of capitalism, and in Dimitrov's theory of fascism as the dictatorship of the most reactionary elements of financial capitalism. The official party line stated that the United States had caused the breakup of the coalition against Hitler.

It was now the bulwark of reaction worldwide, with a heavy reliance on

warmongering for the benefit of the "terrorist international of

murderers on Wall Street". East Germans were told they had a heroic role to play as a front-line against the Americans. However, Western media outlets such as the American Radio Free Europe broadcasts, and West German

media may have limited Anti-Americanism. The official communist media

ridiculed the modernism and cosmopolitanism of American culture, and

denigrated the features of the American way of life, especially jazz

music and rock and roll.

Fascist critiques

Drawing on the ideas of Arthur de Gobineau (1816–1882), European fascists decried the supposed degenerating effect of immigration on the racial mix of the American population. The Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg argued that race mixture in the United States made it inferior to racially pure nations.

Anti-Semitism was another factor in these critiques. The view that the U.S. was controlled by a Jewish conspiracy through a Jewish lobby was common in countries ruled by fascists before and during World War II.

Jews, the assumed puppet masters behind supposed American plans for

world domination, were also seen as using jazz in a crafty plan to

eliminate racial distinctions; Adolf Hitler dismissed the threat of the United States as a credible enemy of Germany because of its incoherent racial mix; he saw Americans as a "mongrel race", "half-Judaized" and "half-Negrified".

In an address to the Reichstag on 11 December 1941, Hitler declared war on the United States and lambasted U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt:

He [Roosevelt] was strengthened in

this [political diversion] by the circle of Jews surrounding him, who,

with Old Testament-like fanaticism, believe that the United States can

be the instrument for preparing another Purim for the European nations that are becoming increasingly anti-Semitic. It was the Jew, in his full Satanic vileness, who rallied around this man [Roosevelt], but to whom this man also reached out.

In 1944, as war was basically lost, the SS published a virulent article in their weekly Das Schwarze Korps titled "Danger of Americanism" which criticized and characterized the American entertainment industry, as it was thought to be owned by the Jews: "Americanism is a splendid method of depoliticization. The Jews have used jazz and movies, magazines and smut, gangsterism and free love, and every perverse desire, to keep the American people so distracted that they pay no attention to their own fate".

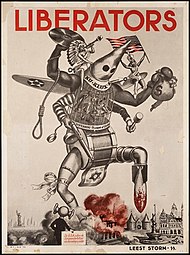

"Liberators" poster

The "Liberators" poster that was distributed by the Nazis to a Dutch

audience in 1944 displays multiple elements of anti-American attitudes

promoted by the Nazis. The title Liberators refers to a common Allied justification for attacking Germany (and possibly the American B-24 Liberator bombers as well), and the poster depicts this "liberation" as the destruction of European cities. The artist was Harald Damsleth, a Norwegian who worked for the NS in occupied Norway.

Motifs contained in this poster include:

- The decadence of beauty pageants (scantily-clad "Miss America"

and "Miss Victory", "The World's Most Beautiful Leg") – or more

generally, the putative sexual laxness of American women. The "Miss America" beauty pageant in Atlantic City had expanded during the war and was used to sell war bonds.

- Gangsterism and gun violence (the arm of an escaped convict holding a submachine gun). Gangsterism had become a theme of anti-Americanism in the 1930s.

- Anti-black violence (a lynching noose, a Ku Klux Klan hood). The lynching of blacks had attracted European denunciations by the 1890s.

- General violence of American society, in addition to the above

(boxing-glove which grasps the money-bag). The theme of a violent

American frontier was well known in the 19th century.

- Americans as Indian savages and as a mockery of American genocide

over Natives as well as land-theft, since it is a chieftain symbol here

used as a fashion trinket. ("Miss America" wears plains-Indian

head-dress).

- The capitalism, pure materialism and commercialism

of America, to the detriment of any spirit or soul (money bag with "$"

symbol). The materialism of America contrasted with the spiritual depth

of European high culture is a common trope, especially in Scandinavia.

- Anti-semitism appears in most Nazi-generated images of America. A Jewish banker is seen behind the money.

- The presence of blacks in America

equals its "mongrelization", adding undesirably "primitive" elements to

American popular culture, and constituting a potential danger to the

white race (a stereotypically-caricatured black couple dancing the "Jitterbug

– Triumph of Civilization" in birdcage, which is portrayed as a

degraded animalistic ritual). The degradation of culture, especially

through miscegenation, resonated with European anxieties, especially in Germany.

- Decadence of American popular culture, and its pernicious influence

on the rest of the world (dancing of jitterbug, hand holds phonograph

record, figure of a European gullible "all-ears" dupe in lower

foreground). The growing popularity of American music and dancing among

young people had ignited a "moral panic" among conservative Europeans.

- Indiscriminate U.S. military violence (bloodied bomb for foot, metal legs, military aircraft wings), threatening the European cultural landmarks at lower right.

- Hence the suggested falsity of American claims to be "Liberators" (the Liberator was also the name of a U.S. bomber plane).

- Nazis denounced American jingoism

and war fervor (a business-suited arm literally "beating the drum" of

militarism, "Miss Victory" and her drum-majorette cap and boots).

- The malevolent influence of American Freemasons (Masonic apron descending from drum) was a theme among conservative Catholics, as in Spain.

- Demonization of national symbols of the United States ("Miss Victory" waves the reverse side of 48-star U.S. flag, and the WW2-era Army Air Corps roundel – of small red disk within white star on large blue disk – is shown on one of the wings).

21st century

September 11 attacks

In a book called The Rise of Anti-Americanism, published in 2006, Brendon O'Connor and Martin Griffiths said that the September 11 attacks were "quintessential anti-American acts, which satisfy all of the competing definitions of Anti-Americanism".

They ask, "If 9/11 can be construed as the exemplar of anti-Americanism

at work, does it make much sense to imply that all anti-Americans are

complicit with terrorism?" Most leaders in Islamic countries, including Afghanistan, condemned the attacks. Saddam Hussein's Ba'athist Iraq was a notable exception, with an immediate official statement that "the American cowboys are reaping the fruit of their crimes against humanity".

Europe was highly sympathetic to the United States after the 9/11 attack. NATO unanimously supported the United States, treating an attack on the U.S. as an attack on all of them after Article 5 of the NATO treaty was invoked for the very first (and, as of 30 August 2022, last) time. NATO and American troops entered Afghanistan. When the United States decided to invade and overthrow the Iraqi regime in 2003, it won some support in Europe, especially from the British government, but also intense opposition, led by the German and French governments. Konrad Jarausch argues that there was still fundamental agreement on such basic issues of support for democracy and human rights. However, there emerged a growing gap between an American "libertarian, individualistic, market outlook, and the more statist, collectivist, welfare mentality in Europe."

U.S. computer technology

A growing dimension of anti-Americanism is fear of the pervasiveness of U.S. Internet technology. This can be traced from the very first computers which were either British (Colossus) or German (Z1) through to the World Wide Web itself (invented by Englishman Tim Berners-Lee). In all these cases the U.S. has commercialized all these innovations.

Americanization has advanced through widespread high speed Internet

and smart phone technology since 2008 and a large fraction of the new

apps and hardware were designed in the United States. In Europe, there

is growing concern about excessive Americanization through Google,

Facebook, Twitter, Apple and Uber, among many other U.S. Internet-based

corporations. European governments have increasingly expressed concern

regarding privacy issues, as well as antitrust and taxation issues

regarding the new American giants. There is fear that they are

significantly evading taxes, and posting information that may violate European privacy laws. The Wall Street Journal in 2015 reported "deep concerns in Europe's highest policy circles about the power of U.S. technology companies."

Mitigation of anti-Americanism

Sometimes developments help neutralize anti-Americanism. In 2015, the United States Department of Justice went on the attack against corruption at FIFA, arresting many top world soccer

leaders long suspected of bribery and corruption. In this case the U.S.

government's self-defined role as "policeman of the world" won

widespread international support.

Regional anti-Americanism

Public opinion on the US (2022)

Europe

Eastern Europe

Russia

Anti-American slogans,

Victory Day in largely Russian-speaking

Donetsk, Ukraine, 9 May 2014

Russia has a long history of anti-Americanism, dating back to 1918.

In some of the latest Russian population polls, the United States and

its allies constantly top the list of "greatest threats".

In 2013, 30% of Russians had a "very unfavorable" or "somewhat

unfavorable" view of Americans and 40% viewed the U.S. in a "very

unfavorable" or "somewhat unfavorable" light, up from 34% in 2012. Recent polls from the Levada center survey show that 71% of Russians have at least a somewhat negative attitude toward the U.S., up from 38% in 2013. It is the largest figure since the collapse of the USSR.

In 2015, a new poll by the Levada center showed that 81% of Russians

now hold unfavorable views of the United States, presumably as a result

of U.S. and Western sanctions imposed against Russia because of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Anti-Americanism in Russia is reportedly at its highest since the end of the Cold War. A December 2017 survey conducted by the Chicago Council

and its Russian partner, the Levada Center, showed that 78% of

"Russians polled said the United States meddles "a great deal" or "a

fair amount" in Russian politics", only 24% of Russians say they hold a

positive view of the United States, and 81% of "Russians said they felt

the United States was working to undermine Russia on the world stage."

Survey results published by the Levada-Center indicate that, as of August 2018, Russians increasingly viewed the United States positively following the Russia–U.S. summit in Helsinki in July 2018. The Moscow Times

reported that "For the first time since 2014, the number of Russians

who said they had "positive" feelings towards the United States (42

percent) outweighed those who reported "negative" feelings (40

percent)." In February 2020, 46% of Russians polled said they had a negative view of the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, "57% of Russians ages 18 to 29 see the U.S. favorably, compared with only 15% of Russians ages 50 and older." In 2019, only 20% of Russians viewed U.S. President Donald Trump positively. Only 14% of Russians expressed net approval of Donald Trump's policies.

Western Europe

Banner expressing anti-American sentiments in

Stockholm, Sweden in 2006

In a 2003 article, historian David Ellwood identified what he called three great roots of anti-Americanism:

- Representations, images and stereotypes (from the birth of the Republic onwards)

- The challenge of economic power and the American model of modernization (principally from the 1910s and 1920s on)

- The organized projection of U.S. political, strategic and ideological power (from World War II on)

He went on to say that expressions of the phenomenon in the last 60

years have contained ever-changing combinations of these elements, the

configurations depending on internal crises within the groups or

societies articulating them as much as anything done by American society

in all its forms.

In 2004, Sergio Fabbrini wrote that the perceived post-9/11 unilateralism of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq

fed deep-rooted anti-American feeling in Europe, bringing it to the

surface. In his article, he highlighted European fears surrounding the

Americanization of the economy, culture and political process of Europe.

Fabbrini in 2011 identified a cycle in anti-Americanism: modest in the

1990s, it grew explosively between 2003 and 2008, then declined after

2008. He sees the current version as related to images of American

foreign policy-making as unrestrained by international institutions or

world opinion. Thus it is the unilateral policy process and the

arrogance of policy makers, not the specific policy decisions, that are

decisive.

During the George W. Bush administration, public opinion of America declined in most European countries. A Pew Research Center

Global Attitudes Project poll showed "favorable opinions" of America

between 2000 and 2006 dropping from 83% to 56% in the United Kingdom,

from 62% to 39% in France, from 78% to 37% in Germany and from 50% to

23% in Spain. In Spain, unfavorable views of Americans rose from 30% in

2005 to 51% in 2006 and positive views of Americans dropped from 56% in

2005 to 37% in 2006.

Anti-war demonstration against a visit by

George W. Bush to London in 2008

In Europe in 2002, vandalism of American companies was reported in Athens, Zürich, Tbilisi, Moscow and elsewhere. In Venice, 8 to 10 masked individuals claiming to be anti-globalists attacked a McDonald's restaurant.

In Athens, at the demonstrations commemorating the 17 November Uprising there was a march toward the U.S. embassy to emphasize the U.S. backing of the Greek military junta of 1967–1974 attended by many people each year.

Ruth Hatlapa, a PhD candidate at the University of Augsburg, and Andrei S. Markovits, a professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan,

describe President Obama's image as that of an angel – or more

precisely, a rock star – in Europe in contrast to Bush's devilish image

there; they argue, however, that "Obamamania" masks a deep-seated

distrust and disdain of America.

France

In France, the term "Anglo-Saxon" is often used in expressions of anti-Americanism or Anglophobia.

French writers have also used it in more nuanced ways in discussions

about French decline, especially as an alternative model to which France

should aspire, how France should adjust to its two most prominent

global competitors, and how it should deal with social and economic

modernization.

The First Indochina War in Indochina and the Suez Crisis of 1956 caused dismay among the French right, which was already angered by the lack of American support during Dien Bien Phu in 1954. For the Socialists and Communists of the French left, it was the Vietnam War and U.S. imperialism that were the sources of resentment. Much later, the alleged weapons of mass destruction in Iraq

affair further dirtied the previously favorable image. In 2008, 85% of

the French people considered the American government and banks to be

most liable for the Financial crisis of 2007–2010.

In her contribution to the seminal book Anti-Americanisms in World Politics edited by Peter Katzenstein and Robert Keohane in 2006, Sophie Meunier

wrote about French anti-Americanism. She contends that although it has a

long history (older than the U.S. itself) and is the most easily

recognizable anti-Americanism in Europe, it may not have had real policy

consequences on the United States and thus may have been less damaging

than more pernicious and invisible anti-Americanism in other countries.

In 2013, 36% viewed the U.S. in a "very unfavorable" or "somewhat unfavorable" light.

Richard Kuisel, an American scholar, has explored how France

partly embraced American consumerism while rejecting much of American

power and values. He wrote in 2013 that:

America functioned as the "other"

in configuring French identity. To be French was not to be American.

Americans were conformists, materialists, racists, violent, and vulgar.

The French were individualists, idealists, tolerant, and civilized.

Americans adored wealth; the French worshiped [sic] la douceur de vivre.

This caricature of America, which was already broadly endorsed at the

beginning of the century, served to reinforce French national identity.

At the end of the twentieth century, the French strategy [was to use]

America as a foil, as a way of defining themselves as well as everything

from their social policies to their notion of what constituted culture.

In October 2016, French President François Hollande

said: "When the (European) Commission goes after Google or digital

giants which do not pay the taxes they should in Europe, America takes

offence. And yet, they quite shamelessly demand 8 billion from BNP or 5

billion from Deutsche Bank." French bank BNP Paribas was fined in 2014 for violating U.S. sanctions against Iran.

Germany

German naval planners in the 1890–1910 era denounced the Monroe Doctrine as a self-aggrandizing legal pretension to dominate the Western hemisphere. They were even more concerned with the possible American canal in Panama,

because it would lead to full American hegemony in the Caribbean. The

stakes were laid out in the German war aims proposed by the Navy in

1903: a "firm position in the West Indies," a "free hand in South

America," and an official "revocation of the Monroe Doctrine" would provide a solid foundation for "our trade to the West Indies, Central and South America."

During the Cold War, anti-Americanism was the official government policy in East Germany,

and dissenters were punished. In West Germany, anti-Americanism was the

common position on the left, but the majority praised America as a

protector against communism and a critical ally in rebuilding the

nation. Germany's refusal to support the American-led 2003 invasion of Iraq was often seen as a manifestation of anti-Americanism. Anti-Americanism had been muted on the right since 1945, but re-emerged in the 21st century especially in the Alternative for Germany

(AfD) party that began in opposition to European Union, and now has

become both anti-American and anti-immigrant. Annoyance or distrust of

the Americans was heightened in 2013 by revelations of American spying on top German officials, including Chancellor Merkel.

In the affair surrounding Der Spiegel journalist Claas Relotius, U.S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell

wrote to the magazine complaining about an anti-American institutional

bias ("Anti-Amerikanismus") and asked for an independent investigation. Grenell wrote that "These fake news stories largely focus on U.S. policies and certain segments of the American people."

German historian Darius Harwardt has noted that from 1980 onwards, the term has seen an increase in usage in German politics, for example to discredit those that wish to close American military bases in Germany.

Greece

Although the Greeks have generally held a favorable attitude towards

America and still do today, with 56.5% holding a favorable view in 2013 and 63% in 2021, Donald Trump was highly unpopular in Greece, with 73% having no confidence in him to do the right thing in world affairs. Joe Biden however is popular among the Greek public, with 67% having confidence in the American president.

Netherlands

Protest against the deployment of Pershing II missiles,

The Hague, 1983

Although the Dutch have generally held a favorable attitude toward

America, there were negative currents in the aftermath of World War II

as the Dutch blamed American policy as the reason why their colonies in Southeast Asia were able to gain independence. They credit their rescue from the Nazis in 1944–45 to the Canadian Army.

Postwar attitudes continued the perennial ambiguity of

anti-Americanism: the love-hate relationship, or willingness to adopt

American cultural patterns while at the same time voicing criticism of

them.

In the 1960s, anti-Americanism revived largely in reaction against the

Vietnam War. Its major early advocates were non-party-affiliated,

left-wing students, journalists, and intellectuals. Dutch public opinion

polls (1975–83) indicate a stable attitude toward the United States;

only 10% of the people were deeply anti-American.

The most strident rhetoric came from the left wing of Dutch politics

and can largely be attributed to the consequences of Dutch participation

in NATO.

United Kingdom

According to a Pew Global Attitudes Project poll, during the George W. Bush administration "favorable opinions" of America between 2000 and 2006 fell from 83% to 56% in the United Kingdom.

News articles and blogs have discussed the negative experiences of Americans living in the United Kingdom.

Anti-American sentiment has become more widespread in the United Kingdom following the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan.

Ireland

Negative sentiment towards American tourists is implied to have risen around 2012 and 2014.

Spain

Asia

East Asia

China

China has a history of anti-Americanism beginning with the general

disdain for foreigners in the early 19th century that culminated in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which the U.S. helped in militarily suppressing.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II, the U.S. provided economic and military assistance to the Chiang Kai-shek government against the Japanese invasion. In particular, the "China Hands" (American diplomats known for their knowledge of China) also attempted to establish diplomatic contacts with Mao Zedong's communist regime in their stronghold in Yan'an, with a goal of fostering unity between the Nationalists and Communists. However, relations soured after communist victory in the Chinese Civil War and the relocation of the Chiang government to Taiwan, together with the start of the Cold War and rise of McCarthyism in U.S. politics. The newly communist China and the U.S. fought a major undeclared war in Korea, 1950–53 and, as a result, President Harry S. Truman began advocating a policy of containment and sent the United States Seventh Fleet to deter a possible communist invasion of Taiwan. The U.S. signed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty

with Taiwan which lasted until 1979 and, during this period, the

communist government in Beijing was not diplomatically recognized by the

U.S. By 1950, virtually all American diplomatic staff had left mainland

China, and one of Mao's political goals was to identify and destroy

factions inside China that might be favorable to capitalism.

Mao initially ridiculed the U.S. as "paper tiger"

occupiers of Taiwan, "the enemy of the people of the world and has

increasingly isolated itself" and "monopoly capitalist groups", and it was argued that Mao never intended friendly relations with the U.S. However, due to the Sino-Soviet split and increasing tension between China and the Soviet Union, US President Richard Nixon signaled a diplomatic rapprochement with communist China, and embarked on an official visit in 1972. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were eventually restored in 1979. After Mao's death, Deng Xiaoping

embarked on economic reforms, and hostility diminished sharply, while

large-scale trade and investments, as well as cultural exchanges became

major factors. Following the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the U.S. placed economic and military sanctions upon China, although official diplomatic relations continued.

In 2013, 53% of Chinese respondents in a Pew survey had a "very unfavorable" or "somewhat unfavorable" view of the U.S.

Relations improved slightly near the end of Obama's term in 2016, with

44% of Chinese respondents expressing an unfavorable view of the U.S

compared to 50% of respondents expressing a favorable view.

There has been a significant increase in anti-Americanism since U.S. President Donald Trump launched a trade war against China, with Chinese media airing Korean War films. In May 2019, Global Times

said that "the trade war with the U.S. at the moment reminds Chinese of

military struggles between China and the U.S. during the Korean War."

Japan

In Japan, objections to the behavior and presence of American

military personnel are sometimes reported as anti-Americanism, such as

the 1995 Okinawa rape incident. As of 2008, the ongoing U.S. military presence on Okinawa remained a contentious issue in Japan.

While protests have arisen because of specific incidents, they

are often reflective of deeper historical resentments. Robert Hathaway,

director of the Wilson Center's Asia program, suggests: "The growth of

anti-American sentiment in both Japan and South Korea must be seen not

simply as a response to American policies and actions, but as reflective

of deeper domestic trends and developments within these Asian

countries". In Japan, a variety of threads have contributed to anti-Americanism in the post-war era, including pacifism on the left, nationalism on the right, and opportunistic worries over American influence in Japanese economic life.

South Korea

Speaking to the Wilson Center, Katharine Moon

notes that while the majority of South Koreans support the American

alliance "anti-Americanism also represents the collective venting of

accumulated grievances that in many instances have lain hidden for

decades".

In the 1990s, scholars, policy makers, and the media noted that

anti-Americanism was motivated by the rejection of authoritarianism and a

resurgent nationalism, this nationalist anti-Americanism continued into

the 2000s fueled by a number of incidents such as the IMF crisis. During the early 1990s, Western princess, prostitutes for American soldiers became a symbol of anti-American nationalism.

"Dear American" is an anti-American song sung by Psy. "Fucking USA" is an anti-American protest song

written by South Korean singer and activist Yoon Min-suk. Strongly

anti-U.S. foreign policy and anti-Bush, the song was written in 2002 at a

time when, following the Apolo Ohno Olympic controversy and an incident in Yangju

in which two Korean middle school students died after being struck by a

U.S. Army vehicle, anti-American sentiment in South Korea reached high

levels. However, by 2009, a majority of South Koreans were reported as having a favorable view of the United States.

In 2014, 58% of South Koreans had a favorable view of the U.S., making

South Korea one of the world's most pro-American countries.

North Korea

Relations between North Korea and the United States have been hostile ever since the Korean War, and the former's more recent development of nuclear weapons and long range missiles has further increased tension between the two nations. The United States currently maintains a military presence in South Korea, and President George W. Bush had previously described North Korea as part of the "Axis of Evil".

In North Korea, July is the "Month of Joint Anti-American Struggle," with festivities to denounce the U.S.

Southeast Asia

Philippines

Student-activists

from University of the Philippines and Ateneo de Manila University burn

the flags of China and US to protest against their encroachment of

Philippine sovereignty.

Anti-American sentiment has existed in the Philippines, owing primarily to the Philippine–American War of more than 100 years ago, and the 1898–1946 period of US colonial rule. One of the country's most recognizable patriotic hymns, Nuestra patria (lit. 'Our Fatherland'; Tagalog: Bayan Ko, lit. 'My Country'), written during the Philippine–American War, makes reference to "the Anglo-Saxon … who with vile treason subjugates [the Fatherland]". The song then exhorts the invaded and later occupied nation to "free [it]self from the traitor."

Mojarro (2020) wrote that, during the US occupation, "Filipino

intellectuals and patriots fully rejected US tutelage of Philippine

politics and the economy," adding that "The Spanish language was understood then as a tool of cultural and political resistance." Manuel L. Quezon himself refused to learn English, having "felt betrayed by the Americans whom [the Katipunan] considered allies against Spain".

Statesman and internationally renowned Hispanophone writer Claro Mayo Recto had once dared to oppose the national security

interests of the US in the Philippines, such as when he campaigned

against the US military bases in his country. During the 1957

presidential campaign, the Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA) conducted black propaganda operations to ensure his defeat,

including the distribution of condoms with holes in them and marked with

"Courtesy of Claro M. Recto" on the labels. The CIA is also suspected of involvement in his death by heart attack

less than three years later. Recto, who had no known heart disease, met

with two mysterious "Caucasians" wearing business suits before he died.

US government documents later showed that a plan to murder Recto with a

vial of poison was discussed by CIA Chief of Station Ralph Lovett and

US Ambassador Admiral Raymond Spruance years earlier.

In October 2012, American ships were found dumping toxic wastes

into Subic Bay, spurring anti-Americanism and setting the stage for

multiple rallies.

When U.S. president Barack Obama toured Asia, in mid to late April 2014

to visit Malaysia, South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines, hundreds of

Filipino protests demonstrated in Manila shouting anti-Obama slogans, with some even burning mock U.S. flags.

The controversial Visiting Forces Agreement adds further fuel to anti-American sentiment, especially among Philippine Muslims. US military personnel have also been tried and convicted for rapes and murders committed on Philippine soil against civilians. These service personnel would later either be freed by the justice system or receive a presidential pardon.

However, despite these incidents, a poll conducted in 2011 by the

BBC found that 90% of Filipinos have a favorable view of the U.S.,

higher than the view of the U.S. in any other country.

According to a Pew Research Center Poll released in 2014, 92% of

Filipinos viewed the U.S. favorably, making the Philippines the most

pro-American nation in the world. The election of Rodrigo Duterte in 2016, along with persistently high approval ratings thereafter, nevertheless herald a new era marked by neonationalism and a resurgent anti-Americanism founded on what had by then been long-unattended historical grievances.

South Asia

Afghanistan

Drone strikes have led to growing anti-Americanism.

Pakistan

Negative attitudes toward the U.S.'s influence on the world has risen in Pakistan as a result of U.S. drone attacks on the country introduced by George W. Bush and continued by Barack Obama. In a poll surveying opinions toward the United States, Pakistan scored

as the most negatively aligned nation, jointly alongside Serbia.

Middle East

After World War I, admiration was expressed for American President Woodrow Wilson's promulgation of democracy, freedom and self-determination in the Fourteen Points and, during World War II, the high ideals of the Atlantic Charter received favorable notice. According to Tamim Ansary, in Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (2009), early views of America were mostly positive in the Middle East and the Muslim World.

Just as they do elsewhere in the world, spikes in

anti-Americanism in the region correlate with the adoption or the

reiteration of certain policies by the U.S. government, in special its support for Israel in the occupation of Palestine and the Iraq War. In regards to 9/11, a Gallup poll noted that while most Muslims

(93%) polled opposed the attacks, 'radicals' (7%) supported it, citing

in their favor, not religious view points, but disgust at U.S. policies. In effect, when targeting U.S. or other Western assets in the region, radical armed groups in the Middle East, Al-Qaeda included, have made reference to U.S. policies and alleged crimes against humanity to justify their attacks. For example, to explain the Khobar Towers bombing (in which 19 American airmen

were killed), Bin Laden, although proven to have not committed the

attack, named U.S. support for Israel in instances of attacks against

Muslims, such as the Sabra and Shatila massacre and the Qana massacre, as the reasons behind the attack.

Al-Qaeda also cited the U.S. sanctions on and bombing of Iraq in the Iraqi no-fly zones (1991–2003), which exacted a large toll in the Arab country's civilian population, as a justification to kill Americans.

Although right-wing scholars (e.g. Paul Hollander)

have given prominence to the role that religiosity, culture and

backwardness play in inflaming anti-Americanism in the region, the poll

noted that radicalism among Arabs or Muslims isn't correlated with

poverty, backwardness or religiosity. Radicals were in fact shown to be

better educated and wealthier than 'moderates'.

There is also, however, a cultural dimension to anti-Americanism

among religious and conservative groups in the Middle East. It may have

its origins with Sayyid Qutb. Qutb, an Egyptian who was the leading intellectual of the Muslim Brotherhood, studied in Greeley, Colorado from 1948 to 1950, and wrote a book, The America I Have Seen

(1951) based on his impressions. In it he decried everything in America

from individual freedom and taste in music to Church socials and

haircuts. Wrote Qutb, "They danced to the tunes of the gramophone,

and the dance floor was replete with tapping feet, enticing legs, arms

wrapped around waists, lips pressed to lips, and chests pressed to

chests. The atmosphere was full of desire..."

He offered a distorted chronology of American history and was disturbed

by its sexually liberated women: "The American girl is well acquainted

with her body's seductive capacity. She knows it lies in the face, and

in expressive eyes, and thirsty lips. She knows seductiveness lies in

the round breasts, the full buttocks, and in the shapely thighs, sleek

legs – and she shows all this and does not hide it". He was particularly disturbed by jazz, which he called the American's preferred music, and which "was created by Negroes to satisfy their love of noise and to whet their sexual desires ..."

Qutb's writings influenced generations of militants and radicals in the

Middle East who viewed America as a cultural temptress bent on

overturning traditional customs and morals, especially with respect to

the relations between the sexes.

Qutb's ideas influenced Osama Bin Laden, an anti-American extremist from Saudi Arabia, who was the founder of the Jihadist organization Al-Qaeda. In conjunction with several other Islamic militant leaders, bin Laden issued two fatawa – in 1996 and then again in 1998

– that Muslims should kill military personnel and civilians of the

United States until the United States government withdraw military

forces from Islamic countries and withdraw support for Israel.

After the 1996 fatwa, entitled "Declaration of War against the

Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places", bin Laden was put

on a criminal file by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under an American Civil War statute which forbids instigating violence and attempting to overthrow the U.S. government. He has also been indicted in United States federal court for his alleged involvement in the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Nairobi, Kenya, and was on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list.

On 14 January 2009, bin Laden vowed to continue the fight and open up

new fronts against the U.S. on behalf of the Islamic world.

In 2002 and in mid-2004, Zogby International polled the favorable/unfavorable ratings of the U.S. in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and the United Arab Emirates

(UAE). In Zogby's 2002 survey, 76% of Egyptians had a negative attitude

toward the United States, compared with 98% in 2004. In Morocco, 61%

viewed the country unfavorably in 2002, but in two years, that number

had jumped to 88 percent. In Saudi Arabia, such responses rose from 87%

in 2002 to 94% in 2004. Attitudes were virtually unchanged in Lebanon

but improved slightly in the UAE, from 87% who said in 2002 that they

disliked the United States to 73% in 2004. However, most of these countries mainly objected to foreign policies that they considered unfair.

Iran

At the Iranian Foreign Ministry, in Tehran, a banner advertising an article written by

Ayatollah Khomeini in which he is quoted as saying that America is the

Great SatanThe chant "Death to America" (Persian: مرگ بر آمریکا) has been in use in Iran since at least the Iranian revolution in 1979, along with other phrases often represented as anti-American. A 1953 coup which involved the CIA was cited as a grievance. State-sponsored murals characterized as anti-American dot the streets of Tehran. It has been suggested that under Ayatollah Khomeini anti-Americanism was little more than a way to distinguish between domestic supporters and detractors, and even the phrase "Great Satan" which has previously been associated with anti-Americanism, appears to now signify both the American and British governments.

The Iran hostage crisis that lasted from 1979 to 1981, in which fifty-two Americans were held hostage in Tehran for 444 days, was also a demonstration of anti-Americanism, one which considerably worsened mutual perceptions between the U.S. and Iran.

Jordan

Anti-Americanism is felt very strongly in Jordan

and has been on the rise since at least 2003. Despite the fact that

Jordan is one of America's closest allies in the Middle East and the Government of Jordan is pro-American and pro-Western, the anti-Americanism of Jordanians is among the highest in the world. Anti-Americanism rose dramatically after the 2003 invasion of Iraq, when a United States-led coalition invaded Iraq to remove Saddam Hussein

from power. According to several Pew Research Attitudes polls conducted

since 2003, 99% of Jordanians viewed the U.S. unfavorably and 82% of

Jordanians viewed American people unfavorably. Although 2017 data

indicates negative attitudes towards the U.S. and American people have

gone down to 82% and 61% respectively, rates of anti-Americanism in

Jordan are still among the highest in the world.

Palestine

In July 2013, Palestinian Cleric Ismat Al-Hammouri, a leader of the Jerusalem-based Hizb ut-Tahrir, called for the destruction of America, France, Britain and Rome

to conquer and destroy the enemies of the "Nation of Islam". He warned:

"We warn you, oh America: Take your hands off the Muslims. You have

wreaked havoc in Syria, and before that, in Afghanistan and in Iraq,

and now in Egypt. Who do you think we are, America? We are the nation

of Islam — a giant and mighty nation, which extends from east to west.

Soon, we will teach you a political and military lesson, Allah willing. Allah Akbar. All glory to Allah".

Al-Hammouri also warned U.S. president Barack Obama that there is an

impending rise of a united Muslim empire that will instill religious law

on all of its subjects.

Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, anti-American sentiment was described as "intense" and "at an all-time high".

According to the survey taken by the Saudi intelligence service of "educated Saudis

between the ages of 25 and 41" taken shortly after the 9/11 attacks

"concluded that 95 percent" of those surveyed supported Bin Laden's

cause. (Support for Bin Laden reportedly waned by 2006 and by then, the Saudi population become considerably more pro-American, after Al-Qaeda linked groups staged attacks inside Saudi Arabia.) The proposal at the Defense Policy Board to 'take Saudi out of Arabia' was spread as the secret US plan for the kingdom.

Turkey

In 2009, during U.S. president Barack Obama's visit to Turkey, anti-American protestors held signs saying "Obama, new president of the American imperialism that is the enemy of the world's people, your hands are also bloody. Get out of our country." Protestors also shouted phrases such as "Yankee go home" and "Obama go home".

A 2017 Pew Research poll indicated that 67% of Turkish respondents held

unfavorable views of Americans and 82% disapproved of the spread of

American ideas and customs in their country; both percentages were the

highest out of all the nations surveyed.

The Americas

All the countries of North and South America (including Canada, the United States of America, and Latin American countries) are often referred to as "The Americas" in the Anglosphere.

In the U.S. and most countries outside Latin America, the terms

"America" and "American" typically refer only to the United States of

America and its citizens respectively. In the 1890s Cuban writer José Martí in an essay, "Our America," alludes to his objection to this usage.

Latin America

Anti-Americanism in Latin America has deep roots and is a key element

of the concept of Latin American identity, "specifically anti-U.S.

expansionism and Catholic anti-Protestantism." An 1828 exchange between William Henry Harrison, the U.S. minister plenipotentiary rebuked President Simón Bolívar of Gran Colombia,

saying "... the strongest of all governments is that which is most

free", calling on Bolívar to encourage the development of a democracy.

In response, Bolívar wrote, "The United States ... seem destined by

Providence to plague America with torments in the name of freedom", a

phrase that achieved fame in Latin America.

The Spanish–American War of 1898, which escalated Cuba's war of independence from Spain, turned the U.S. into a world power and made Cuba a virtual dependency of the United States via the Platt Amendment to the Cuban constitution. The U.S. action was consistent with the Big Stick ideology espoused by Theodore Roosevelt's corollary to the Monroe Doctrine that led to numerous interventions in Central America and the Caribbean, also prompted hatred of the U.S. in other regions of the Americas. A very influential formulation of Latin-American anti-Americanism, engendered by the 1898 war, was the Uruguayan journalist José Enrique Rodó's essay Ariel (1900) in which the spiritual values of the South American Ariel are contrasted to the brutish mass-culture of the American Caliban. This essay had enormous influence throughout Spanish America in the 1910s and 1920s, and prompted resistance to what was seen as American cultural imperialism. Perceived racist attitudes of the White Anglo-Saxon Protestants of the North toward the populations of Latin America also caused resentment.

Anti-U.S. banner in a demonstration in

Brazil, 27 January 2005

The Student Reform that began in the Argentinian University of Cordoba

in 1918, boosted the idea of anti-imperialism throughout Latin America,

and played a fundamental role for launching the concept that was to be

developed over several generations. Already in 1920, the Federación Universitaria Argentina issued a manifesto entitled Denunciation of Imperialism.

Since the 1940s, U.S. relations with Argentina have been tense, when the U.S. feared the regime of General Peron was too close to Nazi Germany. In 1954, American support for the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état against the democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán fueled anti-Americanism in the region. This CIA-sponsored coup prompted a former president of that country, Juan José Arévalo to write a fable entitled The Shark and the Sardines (1961) in which a predatory shark (representing the United States) overawes the sardines of Latin America.

Vice-President Richard Nixon's

tour of South America in 1958 prompted a spectacular eruption of

anti-Americanism. The tour became the focus of violent protests which

climaxed in Caracas, Venezuela where Nixon was almost killed by a raging mob as his motorcade drove from the airport to the city. In response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower assembled troops at Guantanamo Bay and a fleet of battleships in the Caribbean to intervene to rescue Nixon if necessary.

Fidel Castro,

the late revolutionary leader of Cuba, tried throughout his career to

co-ordinate long-standing Latin American resentments against the USA

through military and propagandist means. He was aided in this goal by the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion

of Cuba in 1961, planned and implemented by the American government

against his regime. This disaster damaged American credibility in the

Americas and gave a boost to its critics worldwide. According to Rubin and Rubin, Castro's Second Declaration of Havana,

in February 1962, "constituted a declaration of war on the United

States and the enshrinement of a new theory of anti-Americanism". Castro called America "a vulture...feeding on humanity". The United States embargo against Cuba maintained resentment and Castro's colleague, the famed revolutionary Che Guevara, expressed his hopes during the Vietnam War of "creating a Second or a Third Vietnam" in the Latin American region against the designs of what he believed to be U.S. imperialism.

The United States hastens the

delivery of arms to the puppet governments they see as being

increasingly threatened; it makes them sign pacts of dependence to

legally facilitate the shipment of instruments of repression and death

and of troops to use them.

Many subsequent U.S. interventions against countries in the region,

including democracies, and support for military dictatorships solidified

Latin American anti-Americanism. These include 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, the invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965, U.S. involvement in Operation Condor, the 1973 Chilean and 1976 Argentine coups d'état, and the Salvadoran Civil War, the support of the Contras, the training of future military men, subsequently seen as war criminals, in the School of the Americas and the refusal to extradite a convicted terrorist, U.S. support for dictators such as Chilean Augusto Pinochet, Nicaraguan Anastasio Somoza Debayle, Haitian François Duvalier, Brazilian Emílio Garrastazu Médici, Paraguyan Alfredo Stroessner and pre-1989 Panamanian Manuel Noriega.

Many Latin Americans perceived that neo-liberalism reforms were failures in the 1980s and 1990s and intensified their opposition to the Washington consensus. This led to a resurgence in support for Pan-Americanism, support for popular movements in the region, the nationalization of key industries and centralization of government.

America's tightening of the economic embargo on Cuba in 1996 and 2004

also caused resentment amongst Latin American leaders and prompted them

to use the Rio Group and the Madrid-based Ibero-American Summits as meeting places rather than the United States-dominated OAS. This trend has been reinforced through the creation of a series of regional political bodies such as Unasur and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, and a strong opposition to the materialization of the Washington-sponsored Free Trade Area of the Americas at the 2005 4th Summit of the Americas.

Polls compiled by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs showed in 2006 Argentine public opinion was quite negative regarding America's role in the world.

In 2007, 26% of Argentines had a favorable view of the American people,

with 57% having an unfavorable view. Argentine public opinion of the

United States and U.S. policies improved during the Obama administration, and as of 2010

was divided about evenly (42% to 41%) between those who viewed these

favorably or unfavorably. The ratio remained stable by 2013, with 38% of

Argentinians having a favorable view and 40% having an unfavorable

view.

Furthermore, the renewal of the concession for the U.S. military base in Manta, Ecuador was met by considerable criticism, derision, and even doubt by the supporters of such an expansion. The near-war sparked by the 2008 Andean diplomatic crisis

was expressed by a high-level Ecuadorean military officer as being

carried under American auspices. The officer said "a large proportion of

senior officers," share "the conviction that the United States was an

accomplice in the attack" (launched by the Colombian military on a FARC camp in Ecuador, near the Colombian border).

The Ecuadorean military retaliated by stating the 10-year lease on the

base, which expired in November 2009, would not be renewed and that the

U.S. military presence was expected to be scaled down starting three

months before the expiration date.

Mexico

In the 1836 Texas Revolution, the Mexican province of Texas seceded from Mexico and nine years later, encouraged by the Monroe Doctrine and manifest destiny, the United States annexed the Republic of Texas

- at its request, but against vehement opposition by Mexico, which

refused to recognize the independence of Texas - and began their

expansion into Western North America. Mexican anti-American sentiment was further inflamed by the resulting 1846–1848 Mexican–American War, in which Mexico lost more than half of its territory to the United States.

The Chilean writer Francisco Bilbao predicted in America in Danger

(1856) that the loss of Texas and northern Mexico to "the talons of the

eagle" was just a foretaste of an American bid for world domination. An early exponent of the concept of Latin America, Bilbao excluded Brazil and Paraguay

from it, as well as Mexico, because "Mexico lacked a real republican

consciousness, precisely because of its complicated relationship with

the United States." Interventions by the U.S. prompted a later ruler of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz, to lament: "Poor Mexico, so far from God, and so close to the United States". Mexico's National Museum of Interventions, opened in 1981, is a testament to Mexico's sense of grievance with the United States.

In Mexico during the regime of liberal Porfirio Díaz

(1876-1911), policies favored foreign investment, especially American,

who sought profits in agriculture, ranching, mining, industry, and

infrastructure such as railroads. Their dominance in agriculture and

their acquisition of vast tracts of land at the expense of Mexican small

holders and indigenous communities was a cause for peasant mobilization

in the Mexican Revolution (1910–20). The program of the Liberal Party of Mexico (1906), explicitly called for policies against foreign ownership in Mexico, with the slogan "Mexico for the Mexicans." Land reform in Mexico in the postrevolutionary period had a major impact on these U.S. holdings, where many were expropriated.

Venezuela

Hugo Chávez strongholds in

Caracas slums, Venezuela, often feature political murals with anti-U.S. messages.

Since the start of the Hugo Chávez administration, relations between Venezuela and the United States deteriorated markedly, as Chávez became highly critical of the U.S. foreign policy.

Chávez was known for his anti-American rhetoric. In a speech at the UN

General Assembly, Chávez said that Bush promoted "a false democracy of

the elite" and a "democracy of bombs". Chávez opposed the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 and also condemned the NATO–led military intervention in Libya, calling it an attempt by the West and the U.S. to control the oil in Libya.

In 2015, the Obama administration signed an executive order which

imposed targeted sanctions on seven Venezuelan officials whom the White

House argued were instrumental in human rights violations, persecution

of political opponents and significant public corruption and said that

the country posed an "unusual and extraordinary threat to the national

security and foreign policy of the United States." Nicolás Maduro responded to the sanctions in a couple of ways. He wrote an open letter in a full page ad in The New York Times

in March 2015, stating that Venezuelans were "friends of the American

people" and called President Obama's action of making targeted sanctions

on the alleged human rights abusers a "unilateral and aggressive

measure". Examples of accusations of human rights abuses from the United States to Maduro's government included the murder of Luis Manuel Díaz, a political activist, prior to legislative elections in Venezuela.

Maduro threatened to sue the United States over an executive

order issued by the Obama Administration that declared Venezuela to be a

threat to American security.

He also planned to deliver 10 million signatures, denouncing the United

States' decree declaring the situation in Venezuela an "extraordinary

threat to US national security".

and ordered all schools in the country to hold an "anti-imperialist

day" against the United States with the day's activities including the

"collection of the signatures of the students, and teaching,

administrative, maintenance and cooking personnel".

Maduro further ordered state workers to apply their signatures in

protest, with some workers reporting that firings of state workers

occurred due to their rejection of signing the executive order

protesting the "Obama decree". There were also reports that members of Venezuelan armed forces and their families were ordered to sign against the United States decree.

Canada

A Canadian political cartoon from 1870 of "

Uncle Sam

and his boys," with Canada depicted in the background. Anti-American

rhetoric in Canada during the period typically depicted the US as

disorderly in contrast to Canada.

Anti-Americanism in Canada has unique historic roots. When the Continental Congress was called in 1774, an invitation was sent to Quebec and Nova Scotia. However Canadians expressed little interest in joining the Congress, and the following year the Continental Army invaded Canada, but was defeated at the Battle of Quebec. Although the American Articles of Confederation later pre-approved Canada as a U.S. state, public opinion had turned against them. Soon 40,000 loyalist refugees arrived from the United States, including 2,000 Black Loyalists, many of whom had fought for the Crown against the American revolutionaries. To them, the republic they left behind was violent and anarchic; with Canadian imperialists repeatedly warning against American-style republicanism and democracy as little more than mob rule. Several transgressions that took place in Upper Canada by the US Army during the War of 1812 resulted in a "deep prejudice against the United States," to emerge in the colony after the conflict.

In the early 20th century, Canadian textbooks portrayed the

United States in a negative fashion. The theme was the United States had

abandoned the British Empire,

and as a result, America was disorderly, greedy, and selfishly

individualistic. By the 1930s, there was less concern with the United

States, and more attention given to Canada's peaceful society, and its

efforts on behalf of civilization in World War I. Close cooperation in

the Second World War

led to a much more favorable image. In the 1945-1965 era, the friendly

and peaceful border was stressed. Textbooks emphasized the role of the

United States as an international power and champion of freedom with

Canada as its influential partner.

In 1945-65, there was wide consensus in Canada on foreign and defense policies. Bothwell, Drummond and English state:

That support was remarkably uniform

geographically and racially, both coast to coast and among French and

English. From the CCF on the left to the Social Credit on the right, the

political parties agreed that NATO was a good thing, and communism a

bad thing, that a close association with Europe was desirable, and that

the Commonwealth embodied a glorious past.

However the consensus did not last. By 1957 the Suez Crisis

had alienated Canada from both Britain and France; politicians

distrusted American leadership, businessmen questioned American

financial investments; and intellectuals ridiculed the values of

American television and Hollywood offerings that all Canadians watched.

"Public support for Canada's foreign policy big came unstuck.

Foreign-policy, from being a winning issue for the Liberals, was fast

becoming a losing one."

Apart from the far left, which admired the USSR, anti-Americanism was

first adopted by a few leading historians. As the Cold War grew hotter

after 1947, Harold Innis

grew increasingly hostile to the United States. He warned repeatedly

that Canada was becoming a subservient colony to its much more powerful

southern neighbor. "We are indeed fighting for our lives," he warned,

pointing especially to the "pernicious influence of American

advertising....We can only survive by taking persistent action at

strategic points against American imperialism in all its attractive

guises." His anti-Americanism influenced some younger scholars, including Donald Creighton.

Anti-American sentiment in Canadian television programming was highlighted in a leaked American diplomatic cable

from 2008. While the cable noted that anti-American sentiment in