From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well,

but many states outside the South had adopted laws, beginning in the

late 19th century, banning discrimination in public accommodations and

voting. Southern laws were enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by white Southern Democrat-dominated state legislatures to disenfranchise and remove political and economic gains made by African Americans during the Reconstruction era. Jim Crow laws were enforced until 1965.

In practice, Jim Crow laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America and in some others, beginning in the 1870s. Jim Crow laws were upheld in 1896 in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson, in which the Supreme Court laid out its "separate but equal" legal doctrine concerning facilities for African Americans. Moreover, public education had essentially been segregated since its establishment in most of the South after the Civil War in 1861–1865.

Although in theory, the "equal" segregation doctrine was extended

to public facilities and transportation too, facilities for African

Americans were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to

facilities for white Americans; sometimes, there were no facilities for the black community at all.

Far from equality, as a body of law, Jim Crow institutionalized

economic, educational, political and social disadvantages and second

class citizenship for most African Americans living in the United

States. After the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) was founded in 1909, it became involved in a sustained public

protest and campaigns against the Jim Crow laws, and the so-called

"separate but equal" doctrine.

In 1954, segregation of public schools (state-sponsored) was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education. In some states, it took many years to implement this decision, while the Warren Court continued to rule against Jim Crow legislation in other cases such as Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964). In general, the remaining Jim Crow laws were overruled by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Etymology

The earliest known use of the phrase "Jim Crow law" can be dated to

1884 in a newspaper article summarizing congressional debate. The term appears in 1892 in the title of a New York Times article about Louisiana requiring segregated railroad cars. The origin of the phrase "Jim Crow" has often been attributed to "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of black people performed by white actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface, first performed in 1828. As a result of Rice's fame, Jim Crow

had become by 1838 a pejorative expression meaning "Negro". When

southern legislatures passed laws of racial segregation directed against

African Americans at the end of the 19th century, these statutes became

known as Jim Crow laws.

Origins

In January 1865, an amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery

in the United States was proposed by Congress and ratified as the Thirteenth Amendment on December 18, 1865.

Cover of an early edition of "

Jump Jim Crow" sheet music (c. 1832)

Freedmen voting in New Orleans, 1867

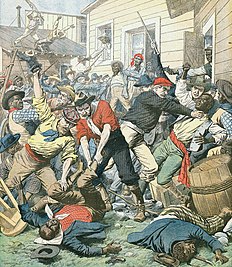

During the Reconstruction era of 1865–1877, federal laws provided civil rights protections in the U.S. South for freedmen, African Americans who were former slaves, and the minority of black people who had been free before the war. In the 1870s, Democrats gradually regained power in the Southern legislatures as violent insurgent paramilitary groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, White League, and Red Shirts

disrupted Republican organizing, ran Republican officeholders out of

town, and lynched Black voters as an intimidation tactic to suppress the

Black vote. Extensive voter fraud was also used. In one instance, an outright coup or insurrection in coastal North Carolina

led to the violent removal of democratically elected Republican party

executive and representative officials, who were either hunted down or

hounded out. Gubernatorial elections were close and had been disputed in Louisiana for years, with increasing violence against black Americans during campaigns from 1868 onward.

The Compromise of 1877 to gain Southern support in the presidential election (a corrupt bargain)

resulted in the government withdrawing the last of the federal troops

from the South. White Democrats had regained political power in every

Southern state. These Southern, white, "Redeemer" governments legislated Jim Crow laws, officially segregating the country's population. Jim Crow laws were a manifestation of authoritarian rule specifically directed at one racial group.

Blacks were still elected to local offices throughout the 1880s

in local areas with large black populations, but their voting was

suppressed for state and national elections. States passed laws to make

voter registration and electoral rules more restrictive, with the result

that political participation by most black people and many poor white people began to decrease. Between 1890 and 1910, ten of the eleven former Confederate states, beginning with Mississippi, passed new constitutions or amendments that effectively disenfranchised most black people and tens of thousands of poor white people through a combination of poll taxes, literacy and comprehension tests, and residency and record-keeping requirements. Grandfather clauses temporarily permitted some illiterate white people to vote but gave no relief to most black people.

Voter turnout dropped dramatically through the South as a result

of these measures. In Louisiana, by 1900, black voters were reduced to

5,320 on the rolls, although they comprised the majority of the state's

population. By 1910, only 730 black people were registered, less than

0.5% of eligible black men. "In 27 of the state's 60 parishes, not a

single black voter was registered any longer; in 9 more parishes, only

one black voter was." The cumulative effect in North Carolina

meant that black voters were completely eliminated from voter rolls

during the period from 1896 to 1904. The growth of their thriving middle

class was slowed. In North Carolina and other Southern states, black

people suffered from being made invisible in the political system:

"[W]ithin a decade of disfranchisement, the white supremacy campaign had erased the image of the black middle class from the minds of white North Carolinians." In Alabama,

tens of thousands of poor whites were also disenfranchised, although

initially legislators had promised them they would not be affected

adversely by the new restrictions.

Those who could not vote were not eligible to serve on juries and

could not run for local offices. They effectively disappeared from

political life, as they could not influence the state legislatures, and

their interests were overlooked. While public schools had been

established by Reconstruction legislatures for the first time in most

Southern states, those for black children were consistently underfunded

compared to schools for white children, even when considered within the

strained finances of the postwar South where the decreasing price of

cotton kept the agricultural economy at a low.

Like schools, public libraries for black people were underfunded,

if they existed at all, and they were often stocked with secondhand

books and other resources. These facilities were not introduced for African Americans in the South until the first decade of the 20th century. Throughout the Jim Crow era, libraries were only available sporadically. Prior to the 20th century, most libraries established for African Americans were school-library combinations.

Many public libraries for both European-American and African-American

patrons in this period were founded as the result of middle-class

activism aided by matching grants from the Carnegie Foundation.

In some cases, progressive measures intended to reduce election fraud, such as the Eight Box Law in South Carolina, acted against black and white voters who were illiterate, as they could not follow the directions. While the separation of African Americans from the white general population was becoming legalized and formalized during the Progressive Era

(1890s–1920s), it was also becoming customary. Even in cases in which

Jim Crow laws did not expressly forbid black people from participating

in sports or recreation, a segregated culture had become common.

In the Jim Crow context, the presidential election of 1912 was steeply slanted against the interests of African Americans.

Most black Americans still lived in the South, where they had been

effectively disfranchised, so they could not vote at all. While poll taxes

and literacy requirements banned many poor or illiterate people from

voting, these stipulations frequently had loopholes that exempted

European Americans from meeting the requirements. In Oklahoma, for instance, anyone qualified to vote before 1866, or related to someone qualified to vote before 1866 (a kind of "grandfather clause"),

was exempted from the literacy requirement; but the only men who had

the franchise before that year were white or European-American. European

Americans were effectively exempted from the literacy testing, whereas

black Americans were effectively singled out by the law.

Woodrow Wilson

was a Democrat elected from New Jersey, but he was born and raised in

the South, and was the first Southern-born president of the post-Civil War period. He appointed Southerners to his Cabinet.

Some quickly began to press for segregated workplaces, although the

city of Washington, D.C., and federal offices had been integrated since

after the Civil War. In 1913, Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo –

an appointee of the President – was heard to express his opinion of

black and white women working together in one government office: "I feel

sure that this must go against the grain of the white women. Is there

any reason why the white women should not have only white women working

across from them on the machines?"

The Wilson administration introduced segregation in federal

offices, despite much protest from African-American leaders and white

progressive groups in the north and midwest.

He appointed segregationist Southern politicians because of his own

firm belief that racial segregation was in the best interest of black

and European Americans alike. At the Great Reunion of 1913 at Gettysburg, Wilson addressed the crowd on July 4, the semi-centennial of Abraham Lincoln's declaration that "all men are created equal":

How complete the union has become

and how dear to all of us, how unquestioned, how benign and majestic, as

state after state has been added to this, our great family of free men!

In sharp contrast to Wilson, a Washington Bee

editorial wondered if the "reunion" of 1913 was a reunion of those who

fought for "the extinction of slavery" or a reunion of those who fought

to "perpetuate slavery and who are now employing every artifice and

argument known to deceit" to present emancipation as a failed venture. Historian David W. Blight observed that the "Peace Jubilee" at which Wilson presided at Gettysburg in 1913 "was a Jim Crow reunion, and white supremacy might be said to have been the silent, invisible master of ceremonies".

In Texas,

several towns adopted residential segregation laws between 1910 and the

1920s. Legal strictures called for segregated water fountains and

restrooms. The exclusion of African Americans also found support in the Republican lily-white movement.

Historical development

Early attempts to break Jim Crow

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, introduced by Charles Sumner and Benjamin F. Butler,

stipulated a guarantee that everyone, regardless of race, color, or

previous condition of servitude, was entitled to the same treatment in

public accommodations, such as inns, public transportation, theaters,

and other places of recreation. This Act had little effect in practice.

An 1883 Supreme Court decision ruled that the act was unconstitutional

in some respects, saying Congress was not afforded control over private

persons or corporations. With white southern Democrats forming a solid

voting bloc in Congress, due to having outsize power from keeping seats

apportioned for the total population in the South (although hundreds of

thousands had been disenfranchised), Congress did not pass another civil

rights law until 1957.

In 1887, Rev. W. H. Heard lodged a complaint with the Interstate Commerce Commission against the Georgia Railroad

company for discrimination, citing its provision of different cars for

white and black/colored passengers. The company successfully appealed

for relief on the grounds it offered "separate but equal" accommodation.

In 1890, Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations

for colored and white passengers on railroads. Louisiana law

distinguished between "white", "black" and "colored" (that is, people of

mixed European and African ancestry). The law had already specified

that black people could not ride with white people, but colored people

could ride with white people before 1890. A group of concerned black,

colored and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association dedicated to rescinding the law. The group persuaded Homer Plessy to test it; he was a man of color who was of fair complexion and one-eighth "Negro" in ancestry.

In 1892, Plessy bought a first-class ticket from New Orleans on

the East Louisiana Railway. Once he had boarded the train, he informed

the train conductor of his racial lineage and took a seat in the

whites-only car. He was directed to leave that car and sit instead in

the "coloreds only" car. Plessy refused and was immediately arrested.

The Citizens Committee of New Orleans fought the case all the way to the

United States Supreme Court. They lost in Plessy v. Ferguson

(1896), in which the Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities

were constitutional. The finding contributed to 58 more years of

legalized discrimination against black and colored people in the United

States.

In 1908, Congress defeated an attempt to introduce segregated streetcars into the capital.

Racism in the United States and defenses of Jim Crow

1904 caricature of "White" and "Jim Crow" rail cars by

John T. McCutcheon.

Despite Jim Crow's legal pretense that the races be "separate but

equal" under the law, non-whites were given inferior facilities and

treatment.

White Southerners encountered problems in learning free labor

management after the end of slavery, and they resented African

Americans, who represented the Confederacy's Civil War defeat: "With white supremacy

being challenged throughout the South, many whites sought to protect

their former status by threatening African Americans who exercised their

new rights."

White Southerners used their power to segregate public spaces and

facilities in law and reestablish social dominance over black people in

the South.

One rationale for the systematic exclusion of African Americans

from southern public society was that it was for their own protection.

An early 20th-century scholar suggested that allowing black people to

attend white schools would mean "constantly subjecting them to adverse

feeling and opinion", which might lead to "a morbid race consciousness". This perspective took anti-black sentiment for granted, because bigotry was widespread in the South after slavery became a racial caste system.

Justifications for white supremacy were provided by scientific racism and negative stereotypes of African Americans.

Social segregation, from housing to laws against interracial chess

games, was justified as a way to prevent black men from having sex with

white women and in particular the rapacious Black Buck stereotype.

World War II and post-war era

In 1944, Associate Justice Frank Murphy introduced the word "racism" into the lexicon of U.S. Supreme Court opinions in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). In his dissenting opinion, Murphy stated that by upholding the forced relocation of Japanese Americans

during World War II, the Court was sinking into "the ugly abyss of

racism". This was the first time that "racism" was used in Supreme Court

opinion (Murphy used it twice in a concurring opinion in Steele v Louisville & Nashville Railway Co 323 192 (1944) issued that day).

Murphy used the word in five separate opinions, but after he left the

court, "racism" was not used again in an opinion for two decades. It

next appeared in the landmark decision of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).

Numerous boycotts and demonstrations against segregation had occurred throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) had been engaged in a series of litigation cases since the

early 20th century in efforts to combat laws that disenfranchised black

voters across the South. Some of the early demonstrations achieved

positive results, strengthening political activism, especially in the

post-World War II years. Black veterans were impatient with social

oppression after having fought for the United States and freedom across

the world. In 1947 K. Leroy Irvis of Pittsburgh's

Urban League, for instance, led a demonstration against employment

discrimination by the city's department stores. It was the beginning of

his own influential political career.

After World War II, people of color increasingly challenged

segregation, as they believed they had more than earned the right to be

treated as full citizens because of their military service and

sacrifices. The civil rights movement was energized by a number of flashpoints, including the 1946 police beating and blinding of World War II veteran Isaac Woodard while he was in U.S. Army uniform. In 1948 President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981, ending racial discrimination in the armed services. That same year, Silas Herbert Hunt enrolled in the University of Arkansas, effectively starting the desegregation of education in the South.

As the civil rights movement gained momentum and used federal

courts to attack Jim Crow statutes, the white-dominated governments of

many of the southern states countered by passing alternative forms of

resistance.

Decline and removal

Historian William Chafe

has explored the defensive techniques developed inside the

African-American community to avoid the worst features of Jim Crow as

expressed in the legal system, unbalanced economic power, and

intimidation and psychological pressure. Chafe says "protective

socialization by black people themselves" was created inside the

community in order to accommodate white-imposed sanctions while subtly

encouraging challenges to those sanctions. Known as "walking the

tightrope," such efforts at bringing about change were only slightly

effective before the 1920s.

However, this did build the foundation for later generations to

advance racial equality and de-segregation. Chafe argued that the places

essential for change to begin were institutions, particularly black

churches, which functioned as centers for community-building and

discussion of politics. Additionally, some all-black communities, such

as Mound Bayou, Mississippi and Ruthville, Virginia served as sources of

pride and inspiration for black society as a whole. Over time, pushback

and open defiance of the oppressive existing laws grew, until it

reached a boiling point in the aggressive, large-scale activism of the

1950s civil rights movement.

Brown v. Board of Education

The NAACP Legal Defense Committee (a group that became independent of the NAACP) – and its lawyer, Thurgood Marshall – brought the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) before the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren. In its pivotal 1954 decision, the Warren Court unanimously (9–0) overturned the 1896 Plessy decision. The Supreme Court found that legally mandated (de jure) public school segregation was unconstitutional. The decision had far-reaching social ramifications.

Integrating collegiate sports

Racial integration of all-white collegiate sports teams was high on

the Southern agenda in the 1950s and 1960s. Involved were issues of

equality, racism, and the alumni demand for the top players needed to

win high-profile games. The Atlantic Coast Conference

(ACC) of flagship state universities in the Southeast took the lead.

First they started to schedule integrated teams from the North. Finally,

ACC schools – typically under pressure from boosters and civil rights

groups – integrated their teams.

With an alumni base that dominated local and state politics, society

and business, the ACC schools were successful in their endeavor – as

Pamela Grundy argues, they had learned how to win:

- The widespread admiration that athletic ability inspired would

help transform athletic fields from grounds of symbolic play to forces

for social change, places where a wide range of citizens could publicly

and at times effectively challenge the assumptions that cast them as

unworthy of full participation in U.S. society. While athletic successes

would not rid society of prejudice or stereotype – black athletes would

continue to confront racial slurs...[minority star players

demonstrated] the discipline, intelligence, and poise to contend for

position or influence in every arena of national life.

Public arena

In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama. This was not the first time this happened – for example, Parks was inspired by 15-year-old Claudette Colvin doing the same thing nine months earlier – but the Parks act of civil disobedience was chosen, symbolically, as an important catalyst in the growth of the post-1954 civil rights movement; activists built the Montgomery bus boycott

around it, which lasted more than a year and resulted in desegregation

of the privately run buses in the city. Civil rights protests and

actions, together with legal challenges, resulted in a series of

legislative and court decisions which contributed to undermining the Jim

Crow system.

End of legal segregation

The decisive action ending segregation came when Congress in bipartisan fashion overcame Southern filibusters to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

A complex interaction of factors came together unexpectedly in the

period 1954–1965 to make the momentous changes possible. The Supreme

Court had taken the first initiative in Brown v. Board of Education

(1954), declaring segregation of public schools unconstitutional.

Enforcement was rapid in the North and border states, but was

deliberately stopped in the South by the movement called Massive Resistance,

sponsored by rural segregationists who largely controlled the state

legislatures. Southern liberals, who counseled moderation, were shouted

down by both sides and had limited impact. Much more significant was the

civil rights movement, especially the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) headed by Martin Luther King Jr.

It largely displaced the old, much more moderate NAACP in taking

leadership roles. King organized massive demonstrations, that seized

massive media attention in an era when network television news was an

innovative and universally watched phenomenon.

SCLC, student activists and smaller local organizations staged

demonstrations across the South. National attention focused on

Birmingham, Alabama, where protesters deliberately provoked Bull Connor

and his police forces by using young teenagers as demonstrators – and

Connor arrested 900 on one day alone. The next day Connor unleashed

billy clubs, police dogs, and high-pressure water hoses to disperse and

punish the young demonstrators with a brutality that horrified the

nation. It was very bad for business, and for the image of a modernizing

progressive urban South. President John F. Kennedy,

who had been calling for moderation, threatened to use federal troops

to restore order in Birmingham. The result in Birmingham was compromise

by which the new mayor opened the library, golf courses, and other city

facilities to both races, against the backdrop of church bombings and

assassinations.

In summer 1963, there were 800 demonstrations in 200 southern

cities and towns, with over 100,000 participants, and 15,000 arrests. In Alabama in June 1963, Governor George Wallace escalated the crisis by defying court orders to admit the first two black students to the University of Alabama. Kennedy responded by sending Congress a comprehensive civil rights bill, and ordered Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy

to file federal lawsuits against segregated schools, and to deny funds

for discriminatory programs. Martin Luther King launched a huge march on

Washington in August 1963, bringing out 200,000 demonstrators in front

of the Lincoln Memorial,

at the time the largest political assembly in the nation's history. The

Kennedy administration now gave full-fledged support to the civil

rights movement, but powerful southern congressmen blocked any

legislation.

After Kennedy was assassinated, President Lyndon B. Johnson

called for immediate passage of Kennedy civil rights legislation as a

memorial to the martyred president. Johnson formed a coalition with

Northern Republicans that led to passage in the House, and with the help

of Republican Senate leader Everett Dirksen

with passage in the Senate early in 1964. For the first time in

history, the southern filibuster was broken and the Senate finally

passed its version on June 19 by vote of 73 to 27.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the most powerful affirmation of

equal rights ever made by Congress. It guaranteed access to public

accommodations such as restaurants and places of amusement, authorized

the Justice Department to bring suits to desegregate facilities in

schools, gave new powers to the Civil Rights Commission;

and allowed federal funds to be cut off in cases of discrimination.

Furthermore, racial, religious and gender discrimination was outlawed

for businesses with 25 or more employees, as well as apartment houses.

The South resisted until the last moment, but as soon as the new law was

signed by President Johnson on July 2, 1964, it was widely accepted

across the nation. There was only a scattering of diehard opposition,

typified by restaurant owner Lester Maddox in Georgia.

In January 1964, President Lyndon Johnson met with civil rights leaders. On January 8, during his first State of the Union address,

Johnson asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the

session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions

combined." On June 21, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi, where they were volunteering in the registration of African American voters as part of the Freedom Summer

project. The disappearance of the three activists captured national

attention and the ensuing outrage was used by Johnson and civil rights

activists to build a coalition of northern and western Democrats and

Republicans and push Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On July 2, 1964, Johnson signed the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964. It invoked the Commerce Clause

to outlaw discrimination in public accommodations (privately owned

restaurants, hotels, and stores, and in private schools and workplaces).

This use of the Commerce Clause was upheld by the Warren Court in the landmark case Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States 379 US 241 (1964).

By 1965, efforts to break the grip of state disenfranchisement by

education for voter registration in southern counties had been underway

for some time, but had achieved only modest success overall. In some

areas of the Deep South, white resistance made these efforts almost

entirely ineffectual. The murder of the three voting-rights activists in

Mississippi in 1964 and the state's refusal to prosecute the murderers,

along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism against black

people, had gained national attention. Finally, the unprovoked attack on March 7, 1965, by county and state troopers on peaceful Alabama marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge en route from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery,

persuaded the President and Congress to overcome Southern legislators'

resistance to effective voting rights enforcement legislation. President

Johnson issued a call for a strong voting rights law and hearings soon

began on the bill that would become the Voting Rights Act.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

ended legally sanctioned state barriers to voting for all federal,

state and local elections. It also provided for federal oversight and

monitoring of counties with historically low minority voter turnout.

Years of enforcement have been needed to overcome resistance, and

additional legal challenges have been made in the courts to ensure the

ability of voters to elect candidates of their choice. For instance,

many cities and counties introduced at-large

election of council members, which resulted in many cases of diluting

minority votes and preventing election of minority-supported candidates.

In 2013, the Roberts Court, in Shelby County v. Holder,

removed the requirement established by the Voting Rights Act that

Southern states needed Federal approval for changes in voting policies.

Several states immediately made changes in their laws restricting

voting access.

Influence and aftermath

African American life

An African American man drinking at a "colored" drinking fountain in a streetcar terminal in

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1939

The Jim Crow laws and the high rate of lynchings in the South were major factors that led to the Great Migration

during the first half of the 20th century. Because opportunities were

very limited in the South, African Americans moved in great numbers to

cities in Northeastern, Midwestern, and Western states to seek better

lives.

African American athletes faced much discrimination during the

Jim Crow era with White opposition leading to their exclusion from most

organized sporting competitions. The boxers Jack Johnson and Joe Louis (both of whom became world heavyweight boxing champions) and track and field athlete Jesse Owens (who won four gold medals at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin) gained prominence during the era. In baseball, a color line instituted in the 1880s had informally barred black people from playing in the major leagues, leading to the development of the Negro leagues, which featured many fine players. A major breakthrough occurred in 1947, when Jackie Robinson

was hired as the first African American to play in Major League

Baseball; he permanently broke the color bar. Baseball teams continued

to integrate in the following years, leading to the full participation

of black baseball players in the Major Leagues in the 1960s.

Interracial marriage

Although sometimes counted among Jim Crow laws of the South, statutes such as anti-miscegenation laws were also passed by other states. Anti-miscegenation laws were not repealed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court (the Warren Court) in a unanimous ruling Loving v. Virginia (1967). Chief Justice Earl Warren

wrote in the court opinion that "the freedom to marry, or not marry, a

person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be

infringed by the State."

Jury trials

The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution

grants criminal defendants the right to a trial by a jury of their

peers. While federal law required that convictions could only be granted

by a unanimous jury for federal crimes, states were free to set their

own jury requirements. All but two states, Oregon and Louisiana, opted

for unanimous juries for conviction. Oregon and Louisiana, however,

allowed juries of at least 10–2 to decide a criminal conviction.

Louisiana's law was amended in 2018 to require a unanimous jury for

criminal convictions, effective in 2019. Prior to that amendment, the

law had been seen as a remnant of Jim Crow laws, because it allowed

minority voices on a jury to be marginalized. In 2020, the Supreme Court

found, in Ramos v. Louisiana,

that unanimous jury votes are required for criminal convictions at

state levels, thereby nullifying Oregon's remaining law, and overturning

previous cases in Louisiana.

Later court cases

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court (the Burger Court), in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, upheld desegregation busing of students to achieve integration.

Interpretation of the Constitution and its application to

minority rights continues to be controversial as Court membership

changes. Observers such as Ian F. Lopez believe that in the 2000s, the

Supreme Court has become more protective of the status quo.

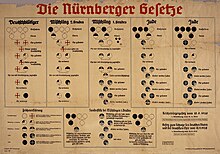

International

There is evidence that the government of Nazi Germany took inspiration from the Jim Crow laws when writing the Nuremberg Laws.

Remembrance

Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, houses the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, an extensive collection of everyday items that promoted racial segregation or presented racial stereotypes of African Americans, for the purpose of academic research and education about their cultural influence.