A barbarian, or savage, is someone who is perceived to be either uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by some to be less civilized or orderly (such as a tribal society) but may also be part of a certain "primitive" cultural group (such as nomads) or social class (such as bandits) both within and outside one's own nation. Alternatively, they may instead be admired and romanticised as noble savages. In idiomatic or figurative usage, a "barbarian" may also be an individual reference to a brutal, cruel, warlike, and insensitive person.

The term originates from the Greek: βάρβαρος (barbaros pl. βάρβαροι barbaroi). In Ancient Greece, the Greeks used the term not only towards those who did not speak Greek and follow classical Greek customs, but also towards Greek populations on the fringe of the Greek world with peculiar dialects. In Ancient Rome, the Romans adapted and used the term towards tribal non-Romans such as the Berbers, Germanics, Celts, Iberians, Thracians, Illyrians, and Sarmatians. In the early modern period and sometimes later, the Byzantine Greeks used it for the Turks in a clearly pejorative manner. In Ancient China, references to barbarians go back as far as the Shang Dynasty and the Spring and Autumn Annals. "Lands beyond moral influence" (Chinese: 化外之地; pinyin: Huà wài zhī dì) or areas outside of range of the Emperor were generally labeled as "Barbarians" or uncivilized through the lens of Sinocentrism.

Etymology

The Ancient Greek name βάρβαρος (bárbaros) or "barbarian" was an antonym for πολίτης (politēs), "citizen" (from πόλις – polis, "city"). The earliest attested form of the word is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀞𐀞𐀫, pa-pa-ro, written in Linear B syllabic script.

The Greeks used the term barbarian for all non-Greek-speaking peoples, including the Egyptians, Persians, Medes and Phoenicians, emphasizing their otherness. According to Greek writers, this was because the language they spoke sounded to Greeks like gibberish represented by the sounds "bar..bar..;" the alleged root of the word βάρβαρος, which is an echomimetic or onomatopoeic word. In various occasions, the term was also used by Greeks, especially the Athenians, to deride other Greek tribes and states (such as Epirotes, Eleans, Macedonians, Boeotians and Aeolic-speakers) and also fellow Athenians in a pejorative and politically motivated manner. The term also carried a cultural dimension to its dual meaning. The verb βαρβαρίζω (barbarízō) in ancient Greek meant to behave or talk like a barbarian, or to hold with the barbarians.

"It was on [the appropriation and adaptation of Egyptian gods] that Greece was founded, according to Plato--and there is no more reliable witness," writes Roberto Calasso in The Celestial Hunter. "The barbarians were therefore the opposite of what the word has come to mean in modern times. They were not new, rough, inarticulate, strong people. They were civilizations much older than Greece--particularly Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia--that had achieved a noble and immovable wisdom." Even in Greek culture, however, the connotations of this word changed over time.

Plato (Statesman 262de) rejected the Greek–barbarian dichotomy as a logical absurdity on just such grounds: dividing the world into Greeks and non-Greeks told one nothing about the second group, yet Plato used the term barbarian frequently in his seventh letter. In Homer's works, the term appeared only once (Iliad 2.867), in the form βαρβαρόφωνος (barbarophonos) ("of incomprehensible speech"), used of the Carians fighting for Troy during the Trojan War. In general, the concept of barbaros did not figure largely in archaic literature before the 5th century BC. It has been suggested that the "barbarophonoi" in the Iliad signifies not those who spoke a non-Greek language but simply those who spoke Greek badly.

A change occurred in the connotations of the word after the Greco-Persian Wars in the first half of the 5th century BC. Here a hasty coalition of Greeks defeated the vast Persian Empire. Indeed, in the Greek of this period 'barbarian' is often used expressly to refer to Persians, who were enemies of the Greeks in this war.

The Romans used the term barbarus for uncivilised people, opposite to Greek or Roman, and in fact, it became a common term to refer to all foreigners among Romans after Augustus age (as, among the Greeks, after the Persian wars, the Persians), including the Germanic peoples, Persians, Gauls, Phoenicians and Carthaginians.

The Greek term barbaros was the etymological source for many words meaning "barbarian", including English barbarian, which was first recorded in 16th century Middle English.

A word barbara- is also found in the Sanskrit of ancient India, with the primary meaning of "stammering" implying someone with an unfamiliar language. The Greek word barbaros is related to Sanskrit barbaras (stammering). This Indo-European root is also found in Latin balbus for "stammering" and Czech blblati "to stammer". The verb baṛbaṛānā in both contemporary Hindi (बड़बड़ाना) as well as Urdu (بڑبڑانا) means 'to babble, to speak gibberish, to rave incoherently'.

In Aramaic, Old Persian and Arabic context, the root refers to "babble confusedly". It appears as barbary or in Old French barbarie, itself derived from the Arabic Barbar, Berber, which is an ancient Arabic term for the North African inhabitants west of Egypt. The Arabic word might be ultimately from Greek barbaria.

Semantics

The Oxford English Dictionary gives five definitions of the noun barbarian, including an obsolete Barbary usage.

- 1. Etymologically, A foreigner, one whose language and customs differ from the speaker's.

- 2. Hist. a. One not a Greek. b. One living outside the pale of the Roman Empire and its civilization, applied especially to the northern nations that overthrew them. c. One outside the pale of Christian civilization. d. With the Italians of the Renaissance: One of a nation outside of Italy.

- 3. A rude, wild, uncivilized person. b. Sometimes distinguished from savage (perh. with a glance at 2). c. Applied by the Chinese contemptuously to foreigners.

- 4. An uncultured person, or one who has no sympathy with literary culture.

- †5. A native of Barbary. [See Barbary Coast.] Obs. †b. Barbary pirates & A Barbary horse. Obs.

The OED barbarous entry summarizes the semantic history. "The sense-development in ancient times was (with the Greeks) 'foreign, non-Hellenic,' later 'outlandish, rude, brutal'; (with the Romans) 'not Latin nor Greek,' then 'pertaining to those outside the Roman Empire'; hence 'uncivilized, uncultured,' and later 'non-Christian,' whence 'Saracen, heathen'; and generally 'savage, rude, savagely cruel, inhuman.'"

In classical Greco-Roman contexts

Historical developments

Greek attitudes towards "barbarians" developed in parallel with the growth of chattel slavery – especially in Athens. Although the enslavement of Greeks for non-payment of debts continued in most Greek states, Athens banned this practice under Solon in the early 6th century BC. Under the Athenian democracy established ca. 508 BC, slavery came into use on a scale never before seen among the Greeks. Massive concentrations of slaves worked under especially brutal conditions in the silver mines at Laureion in south-eastern Attica after the discovery of a major vein of silver-bearing ore there in 483 BC, while the phenomenon of skilled slave craftsmen producing manufactured goods in small factories and workshops became increasingly common.

Furthermore, slave-ownership no longer became the preserve of the rich: all but the poorest of Athenian households came to have slaves in order to supplement the work of their free members. The slaves of Athens that had "barbarian" origins were coming especially from lands around the Black Sea such as Thrace and Taurica (Crimea), while Lydians, Phrygians and Carians came from Asia Minor. Aristotle (Politics 1.2–7; 3.14) characterises barbarians as slaves by nature.

From this period, words like barbarophonos, cited above from Homer, came into use not only for the sound of a foreign language but also for foreigners who spoke Greek improperly. In the Greek language, the word logos expressed both the notions of "language" and "reason", so Greek-speakers readily conflated speaking poorly with stupidity.

Further changes occurred in the connotations of barbari/barbaroi in Late Antiquity, when bishops and catholikoi were appointed to sees connected to cities among the "civilized" gentes barbaricae such as in Armenia or Persia, whereas bishops were appointed to supervise entire peoples among the less settled.

Eventually the term found a hidden meaning through the folk etymology of Cassiodorus (c. 485 – c. 585). He stated that the word barbarian was "made up of barba (beard) and rus (flat land); for barbarians did not live in cities, making their abodes in the fields like wild animals".

Hellenic stereotypes

From classical origins the Hellenic stereotype of barbarism evolved: barbarians are like children, unable to speak or reason properly, cowardly, effeminate, luxurious, cruel, unable to control their appetites and desires, politically unable to govern themselves. Writers voiced these stereotypes with much shrillness – Isocrates in the 4th century B.C., for example, called for a war of conquest against Persia as a panacea for Greek problems.

However, the disparaging Hellenic stereotype of barbarians did not totally dominate Hellenic attitudes. Xenophon (died 354 B.C.), for example, wrote the Cyropaedia, a laudatory fictionalised account of Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Persian Empire, effectively a utopian text. In his Anabasis, Xenophon's accounts of the Persians and other non-Greeks who he knew or encountered show few traces of the stereotypes.

In Plato's Protagoras, Prodicus of Ceos calls "barbarian" the Aeolian dialect that Pittacus of Mytilene spoke.

Aristotle makes the difference between Greeks and barbarians one of the central themes of his book on Politics, and quotes Euripides approvingly, "Tis meet that Greeks should rule barbarians".

The renowned orator Demosthenes (384–322 B.C.) made derogatory comments in his speeches, using the word "barbarian".

In the Bible's New Testament, St. Paul (from Tarsus) – lived about A.D. 5 to about A.D. 67) uses the word barbarian in its Hellenic sense to refer to non-Greeks (Romans 1:14), and he also uses it to characterise one who merely speaks a different language (1 Corinthians 14:11).

About a hundred years after Paul's time, Lucian – a native of Samosata, in the former kingdom of Commagene, which had been absorbed by the Roman Empire and made part of the province of Syria – used the term "barbarian" to describe himself. Because he was a noted satirist, this could have indicated self-deprecating irony. It might also have suggested descent from Samosata's original Semitic population – who were likely called "barbarians by later Hellenistic, Greek-speaking settlers", and might have eventually taken up this appellation themselves.

The term retained its standard usage in the Greek language throughout the Middle Ages; Byzantine Greeks used it widely until the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire, (later named the Byzantine Empire) in the 15th century (1453 with the fall of capital city Constantinople}.

Cicero (106–43 BC) described the mountain area of inner Sardinia as "a land of barbarians", with these inhabitants also known by the manifestly pejorative term latrones mastrucati ("thieves with a rough garment in wool"). The region, still known as "Barbagia" (in Sardinian Barbàgia or Barbàza), preserves this old "barbarian" designation in its name – but it no longer consciously retains "barbarian" associations: the inhabitants of the area themselves use the name naturally and unaffectedly.

The Dying Galatian statue

The statue of the Dying Galatian provides some insight into the Hellenistic perception of and attitude towards "Barbarians". Attalus I of Pergamon (ruled 241–197 BC) commissioned (220s BC) a statue to celebrate his victory (ca 232 BC) over the Celtic Galatians in Anatolia (the bronze original is lost, but a Roman marble copy was found in the 17th century). The statue depicts with remarkable realism a dying Celt warrior with a typically Celtic hairstyle and moustache. He sits on his fallen shield while a sword and other objects lie beside him. He appears to be fighting against death, refusing to accept his fate.

The statue serves both as a reminder of the Celts' defeat, thus demonstrating the might of the people who defeated them, and a memorial to their bravery as worthy adversaries. As H. W. Janson comments, the sculpture conveys the message that "they knew how to die, barbarians that they were".

Utter barbarism, civilization, and the noble savage

The Greeks admired Scythians and Galatians as heroic individuals – and even (as in the case of Anacharsis) as philosophers – but they regarded their culture as barbaric. The Romans indiscriminately characterised the various Germanic tribes, the settled Gauls, and the raiding Huns as barbarians, and subsequent classically oriented historical narratives depicted the migrations associated with the end of the Western Roman Empire as the "barbarian invasions".

The Romans adapted the term in order to refer to anything that was non-Roman. The German cultural historian Silvio Vietta points out that the meaning of the word "barbarous" has undergone a semantic change in modern times, after Michel de Montaigne used it to characterize the activities of the Spaniards in the New World – representatives of the more technologically advanced, higher European culture – as "barbarous," in a satirical essay published in the year 1580. It was not the supposedly "uncivilized" Indian tribes who were "barbarous", but the conquering Spaniards. Montaigne argued that Europeans noted the barbarism of other cultures but not the crueler and more brutal actions of their own societies, particularly (in his time) during the so-called religious wars. In Montaigne's view, his own people – the Europeans – were the real "barbarians". In this way, the argument was turned around and applied to the European invaders. With this shift in meaning, a whole literature arose in Europe that characterized the indigenous Indian peoples as innocent, and the militarily superior Europeans as "barbarous" intruders invading a paradisical world.

In non-Western historical contexts

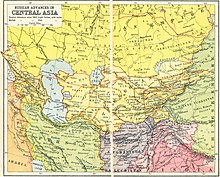

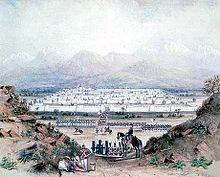

Historically, the term barbarian has seen widespread use in English. Many peoples have dismissed alien cultures and even rival civilizations, because they were unrecognizably strange. For instance, the nomadic Turkic peoples north of the Black Sea, including the Pechenegs and the Kipchaks, were called barbarians by the Byzantines.

Middle East and North Africa

The native Berbers of North Africa were among the many peoples called "Barbarian" by the early Romans. The term continued to be used by medieval Arabs (see Berber etymology) before being replaced by "Amazigh". In English, the term "Berber" continues to be used as an exonym. The geographical term Barbary or Barbary Coast, and the name of the Barbary pirates based on that coast (and who were not necessarily Berbers) were also derived from it.

The term has also been used to refer to people from Barbary, a region encompassing most of North Africa. The name of the region, Barbary, comes from the Arabic word Barbar, possibly from the Latin word barbaricum, meaning "land of the barbarians."

Many languages define the "Other" as those who do not speak one's language; Greek barbaroi was paralleled by Arabic ajam "non-Arabic speakers; non-Arabs; (especially) Persians."

India

In the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata, the Sanskrit onomatopoeic word barbara- referred to the incomprehensible, unfamiliar speech (perceived as "babbling", "incoherent stammering") of non-Vedic peoples ("wretch, foreigner, sinful people, low and barbarous".)

Sinosphere

China

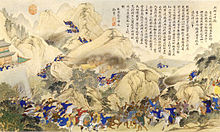

The term "Barbarian" in traditional Chinese culture had several aspects. For one thing, Chinese has more than one historical "barbarian" exonym. Several historical Chinese characters for non-Chinese peoples were graphic pejoratives. The character for the Yao people, for instance, was changed from yao 猺 "jackal" to yao 瑤 "precious jade" in the modern period. The original Hua–Yi distinction between Hua ("Chinese") and Yi (commonly translated as "barbarian") was based on culture and power but not on race.

Historically, the Chinese used various words for foreign ethnic groups. They include terms like 夷 Yi, which is often translated as "barbarians." Despite this conventional translation, there are also other ways of translating Yi into English. Some of the examples include "foreigners," "ordinary others," "wild tribes," "uncivilized tribes," and so forth.

History and terminology

Chinese historical records mention what may now perhaps be termed "barbarian" peoples for over four millennia, although this considerably predates the Greek language origin of the term "barbarian", at least as is known from the thirty-four centuries of written records in the Greek language. The sinologist Herrlee Glessner Creel said, "Throughout Chinese history "the barbarians" have been a constant motif, sometimes minor, sometimes very major indeed. They figure prominently in the Shang oracle inscriptions, and the dynasty that came to an end only in 1912 was, from the Chinese point of view, barbarian."

Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BC) oracles and bronze inscriptions first recorded specific Chinese exonyms for foreigners, often in contexts of warfare or tribute. King Wu Ding (r. 1250–1192 BC), for instance, fought with the Guifang 鬼方, Di 氐, and Qiang 羌 "barbarians."

During the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC), the meanings of four exonyms were expanded. "These included Rong, Yi, Man, and Di—all general designations referring to the barbarian tribes." These Siyi 四夷 "Four Barbarians", most "probably the names of ethnic groups originally," were the Yi or Dongyi 東夷 "eastern barbarians," Man or Nanman 南蠻 "southern barbarians," Rong or Xirong 西戎 "western barbarians," and Di or Beidi 北狄 "northern barbarians." The Russian anthropologist Mikhail Kryukov concluded.

Evidently, the barbarian tribes at first had individual names, but during about the middle of the first millennium B.C., they were classified schematically according to the four cardinal points of the compass. This would, in the final analysis, mean that once again territory had become the primary criterion of the we-group, whereas the consciousness of common origin remained secondary. What continued to be important were the factors of language, the acceptance of certain forms of material culture, the adherence to certain rituals, and, above all, the economy and the way of life. Agriculture was the only appropriate way of life for the Hua-Hsia.

The Chinese classics use compounds of these four generic names in localized "barbarian tribes" exonyms such as "west and north" Rongdi, "south and east" Manyi, Nanyibeidi "barbarian tribes in the south and the north," and Manyirongdi "all kinds of barbarians." Creel says the Chinese evidently came to use Rongdi and Manyi "as generalized terms denoting 'non-Chinese,' 'foreigners,' 'barbarians'," and a statement such as "the Rong and Di are wolves" (Zuozhuan, Min 1) is "very much like the assertion that many people in many lands will make today, that 'no foreigner can be trusted'."

The Chinese had at least two reasons for vilifying and depreciating the non-Chinese groups. On the one hand, many of them harassed and pillaged the Chinese, which gave them a genuine grievance. On the other, it is quite clear that the Chinese were increasingly encroaching upon the territory of these peoples, getting the better of them by trickery, and putting many of them under subjection. By vilifying them and depicting them as somewhat less than human, the Chinese could justify their conduct and still any qualms of conscience.

This word Yi has both specific references, such as to Huaiyi 淮夷 peoples in the Huai River region, and generalized references to "barbarian; foreigner; non-Chinese." Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage translates Yi as "Anc[ient] barbarian tribe on east border, any border or foreign tribe." The sinologist Edwin G. Pulleyblank says the name Yi "furnished the primary Chinese term for 'barbarian'," but "Paradoxically the Yi were considered the most civilized of the non-Chinese peoples.

Idealization

Some Chinese classics romanticize or idealize barbarians, comparable to the western noble savage construct. For instance, the Confucian Analects records:

- The Master said, The [夷狄] barbarians of the East and North have retained their princes. They are not in such a state of decay as we in China.

- The Master said, The Way makes no progress. I shall get upon a raft and float out to sea.

- The Master wanted to settle among the [九夷] Nine Wild Tribes of the East. Someone said, I am afraid you would find it hard to put up with their lack of refinement. The Master said, Were a true gentleman to settle among them there would soon be no trouble about lack of refinement.

The translator Arthur Waley noted that, "A certain idealization of the 'noble savage' is to be found fairly often in early Chinese literature", citing the Zuo Zhuan maxim, "When the Emperor no longer functions, learning must be sought among the 'Four Barbarians,' north, west, east, and south." Professor Creel said,

From ancient to modern times the Chinese attitude toward people not Chinese in culture—"barbarians"—has commonly been one of contempt, sometimes tinged with fear ... It must be noted that, while the Chinese have disparaged barbarians, they have been singularly hospitable both to individuals and to groups that have adopted Chinese culture. And at times they seem to have had a certain admiration, perhaps unwilling, for the rude force of these peoples or simpler customs.

In a somewhat related example, Mencius believed that Confucian practices were universal and timeless, and thus followed by both Hua and Yi, "Shun was an Eastern barbarian; he was born in Chu Feng, moved to Fu Hsia, and died in Ming T'iao. King Wen was a Western barbarian; he was born in Ch'i Chou and died in Pi Ying. Their native places were over a thousand li apart, and there were a thousand years between them. Yet when they had their way in the Central Kingdoms, their actions matched like the two halves of a tally. The standards of the two sages, one earlier and one later, were identical."

The prominent (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi character dictionary, defines yi 夷 as "men of the east" 東方之人也. The dictionary also informs that Yi is not dissimilar from the Xia 夏, which means Chinese. Elsewhere in the Shuowen Jiezi, under the entry of qiang 羌, the term yi is associated with benevolence and human longevity. Yi countries are therefore virtuous places where people live long lives. This is why Confucius wanted to go to yi countries when the dao could not be realized in the central states.

Pejorative Chinese characters

Some Chinese characters used to transcribe non-Chinese peoples were graphically pejorative ethnic slurs, in which the insult derived not from the Chinese word but from the character used to write it. For instance, the Written Chinese transcription of Yao "the Yao people", who primarily live in the mountains of southwest China and Vietnam. When 11th-century Song Dynasty authors first transcribed the exonym Yao, they insultingly chose yao 猺 "jackal" from a lexical selection of over 100 characters pronounced yao (e.g., 腰 "waist", 遙 "distant", 搖 "shake"). During a series of 20th-century Chinese language reforms, this graphic pejorative 猺 (written with the 犭"dog/beast radical") "jackal; the Yao" was replaced twice; first with the invented character yao 傜 (亻"human radical") "the Yao", then with yao 瑤 (玉 "jade radical") "precious jade; the Yao." Chinese orthography (symbols used to write a language) can provide unique opportunities to write ethnic insults logographically that do not exist alphabetically. For the Yao ethnic group, there is a difference between the transcriptions Yao 猺 "jackal" and Yao 瑤 "jade" but none between the romanizations Yao and Yau.

Cultural and racial barbarianism

According to the archeologist William Meacham, it was only by the time of the late Shang dynasty that one can speak of "Chinese," "Chinese culture," or "Chinese civilization." "There is a sense in which the traditional view of ancient Chinese history is correct (and perhaps it originated ultimately in the first appearance of dynastic civilization): those on the fringes and outside this esoteric event were "barbarians" in that they did not enjoy (or suffer from) the fruit of civilization until they were brought into close contact with it by an imperial expansion of the civilization itself." In a similar vein, Creel explained the significance of Confucian li "ritual; rites; propriety".

The fundamental criterion of "Chinese-ness," anciently and throughout history, has been cultural. The Chinese have had a particular way of life, a particular complex of usages, sometimes characterized as li. Groups that conformed to this way of life were, generally speaking, considered Chinese. Those that turned away from it were considered to cease to be Chinese. ... It was the process of acculturation, transforming barbarians into Chinese, that created the great bulk of the Chinese people. The barbarians of Western Chou times were, for the most part, future Chinese, or the ancestors of future Chinese. This is a fact of great importance. ... It is significant, however, that we almost never find any references in the early literature to physical differences between Chinese and barbarians. Insofar as we can tell, the distinction was purely cultural.

Dikötter says,

Thought in ancient China was oriented towards the world, or tianxia, "all under heaven." The world was perceived as one homogenous unity named "great community" (datong) The Middle Kingdom [China], dominated by the assumption of its cultural superiority, measured outgroups according to a yardstick by which those who did not follow the "Chinese ways" were considered "barbarians." A Theory of "using the Chinese ways to transform the barbarian" as strongly advocated. It was believed that the barbarian could be culturally assimilated. In the Age of Great Peace, the barbarians would flow in and be transformed: the world would be one.

According to the Pakistani academic M. Shahid Alam, "The centrality of culture, rather than race, in the Chinese world view had an important corollary. Nearly always, this translated into a civilizing mission rooted in the premise that 'the barbarians could be culturally assimilated'"; namely laihua 來化 "come and be transformed" or Hanhua 漢化 "become Chinese; be sinicized."

Two millennia before the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote The Raw and the Cooked, the Chinese differentiated "raw" and "cooked" categories of barbarian peoples who lived in China. The shufan 熟番 "cooked [food eating] barbarians" are sometimes interpreted as Sinicized, and the shengfan 生番 "raw [food eating] barbarians" as not Sinicized. The Liji gives this description.

The people of those five regions – the Middle states, and the [Rong], [Yi] (and other wild tribes around them) – had all their several natures, which they could not be made to alter. The tribes on the east were called [Yi]. They had their hair unbound, and tattooed their bodies. Some of them ate their food without its being cooked with fire. Those on the south were called Man. They tattooed their foreheads, and had their feet turned toward each other. Some of them ate their food without its being cooked with fire. Those on the west were called [Rong]. They had their hair unbound, and wore skins. Some of them did not eat grain-food. Those on the north were called [Di]. They wore skins of animals and birds, and dwelt in caves. Some of them did not eat grain-food.

Dikötter explains the close association between nature and nurture. "The shengfan, literally 'raw barbarians', were considered savage and resisting. The shufan, or 'cooked barbarians', were tame and submissive. The consumption of raw food was regarded as an infallible sign of savagery that affected the physiological state of the barbarian."

Some Warring States period texts record a belief that the respective natures of the Chinese and the barbarian were incompatible. Mencius, for instance, once stated: "I have heard of the Chinese converting barbarians to their ways, but not of their being converted to barbarian ways." Dikötter says, "The nature of the Chinese was regarded as impermeable to the evil influences of the barbarian; no retrogression was possible. Only the barbarian might eventually change by adopting Chinese ways."

However, different thinkers and texts convey different opinions on this issue. The prominent Tang Confucian Han Yu, for example, wrote in his essay Yuan Dao the following: "When Confucius wrote the Chunqiu, he said that if the feudal lords use Yi ritual, then they should be called Yi; If they use Chinese rituals, then they should be called Chinese." Han Yu went on to lament in the same essay that the Chinese of his time might all become Yi because the Tang court wanted to put Yi laws above the teachings of the former kings. Therefore, Han Yu's essay shows the possibility that the Chinese can lose their culture and become the uncivilized outsiders, and that the uncivilized outsiders have the potential to become Chinese.

After the Song Dynasty, many of China's rulers in the north were of Inner Asia ethnicities, such as the Khitans, Juchens, and Mongols of the Liao, Jin and Yuan Dynasties, the latter ended up ruling over the entire China. Hence, the historian John King Fairbank wrote, "the influence on China of the great fact of alien conquest under the Liao-Jin-Yuan dynasties is just beginning to be explored." During the Qing Dynasty, the rulers of China adopted Confucian philosophy and Han Chinese institutions to show that the Manchu rulers had received the Mandate of Heaven to rule China. At the same time, they also tried to retain their own indigenous culture. Due to the Manchus' adoption of Han Chinese culture, most Han Chinese (though not all) did accept the Manchus as the legitimate rulers of China. Similarly, according to Fudan University historian Yao Dali, even the supposedly "patriotic" hero Wen Tianxiang of the late Song and early Yuan period did not believe the Mongol rule to be illegitimate. In fact, Wen was willing to live under Mongol rule as long as he was not forced to be a Yuan dynasty official, out of his loyalty to the Song dynasty. Yao explains that Wen chose to die in the end because he was forced to become a Yuan official. So, Wen chose death due to his loyalty to his dynasty, not because he viewed the Yuan court as a non-Chinese, illegitimate regime and therefore refused to live under their rule. Yao also says that many Chinese who were living in the Yuan-Ming transition period also shared Wen's beliefs of identifying with and putting loyalty towards one's dynasty above racial/ethnic differences. Many Han Chinese writers did not celebrate the collapse of the Mongols and the return of the Han Chinese rule in the form of the Ming dynasty government at that time. Many Han Chinese actually chose not to serve in the new Ming court at all due to their loyalty to the Yuan. Some Han Chinese also committed suicide on behalf of the Mongols as a proof of their loyalty. The founder of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang, also indicated that he was happy to be born in the Yuan period and that the Yuan did legitimately receive the Mandate of Heaven to rule over China. On a side note, one of his key advisors, Liu Ji, generally supported the idea that while the Chinese and the non-Chinese are different, they are actually equal. Liu was therefore arguing against the idea that the Chinese were and are superior to the "Yi."

These things show that many times, pre-modern Chinese did view culture (and sometimes politics) rather than race and ethnicity as the dividing line between the Chinese and the non-Chinese. In many cases, the non-Chinese could and did become the Chinese and vice versa, especially when there was a change in culture.

Modern reinterpretations

According to the historian Frank Dikötter, "The delusive myth of a Chinese antiquity that abandoned racial standards in favour of a concept of cultural universalism in which all barbarians could ultimately participate has understandably attracted some modern scholars. Living in an unequal and often hostile world, it is tempting to project the utopian image of a racially harmonious world into a distant and obscure past."

The politician, historian, and diplomat K. C. Wu analyzes the origin of the characters for the Yi, Man, Rong, Di, and Xia peoples and concludes that the "ancients formed these characters with only one purpose in mind—to describe the different ways of living each of these people pursued." Despite the well-known examples of pejorative exonymic characters (such as the "dog radical" in Di), he claims there is no hidden racial bias in the meanings of the characters used to describe these different peoples, but rather the differences were "in occupation or in custom, not in race or origin." K. C. Wu says the modern character 夷 designating the historical "Yi peoples," composed of the characters for 大 "big (person)" and 弓 "bow", implies a big person carrying a bow, someone to perhaps be feared or respected, but not to be despised. However, differing from K. C. Wu, the scholar Wu Qichang believes that the earliest oracle bone script for yi 夷 was used interchangeably with shi 尸 "corpse". The historian John Hill explains that Yi "was used rather loosely for non-Chinese populations of the east. It carried the connotation of people ignorant of Chinese culture and, therefore, 'barbarians'."

Christopher I. Beckwith makes the extraordinary claim that the name "barbarian" should only be used for Greek historical contexts, and is inapplicable for all other "peoples to whom it has been applied either historically or in modern times." Beckwith notes that most specialists in East Asian history, including him, have translated Chinese exonyms as English "barbarian." He believes that after academics read his published explanation of the problems, except for direct quotations of "earlier scholars who use the word, it should no longer be used as a term by any writer."

The first problem is that, "it is impossible to translate the word barbarian into Chinese because the concept does not exist in Chinese," meaning a single "completely generic" loanword from Greek barbar-. "Until the Chinese borrow the word barbarian or one of its relatives, or make up a new word that explicitly includes the same basic ideas, they cannot express the idea of the 'barbarian' in Chinese.". The usual Standard Chinese translation of English barbarian is yemanren (traditional Chinese: 野蠻人; simplified Chinese: 野蛮人; pinyin: yěmánrén), which Beckwith claims, "actually means 'wild man, savage'. That is very definitely not the same thing as 'barbarian'." Despite this semantic hypothesis, Chinese-English dictionaries regularly translate yemanren as "barbarian" or "barbarians." Beckwith concedes that the early Chinese "apparently disliked foreigners in general and looked down on them as having an inferior culture," and pejoratively wrote some exonyms. However, he purports, "The fact that the Chinese did not like foreigner Y and occasionally picked a transcriptional character with negative meaning (in Chinese) to write the sound of his ethnonym, is irrelevant."

Beckwith's second problem is with linguists and lexicographers of Chinese. "If one looks up in a Chinese-English dictionary the two dozen or so partly generic words used for various foreign peoples throughout Chinese history, one will find most of them defined in English as, in effect, 'a kind of barbarian'. Even the works of well-known lexicographers such as Karlgren do this." Although Beckwith does not cite any examples, the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren edited two dictionaries: Analytic Dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese (1923) and Grammata Serica Recensa (1957). Compare Karlgrlen's translations of the siyi "four barbarians":

- yi 夷 "barbarian, foreigner; destroy, raze to the ground," "barbarian (esp. tribes to the East of ancient China)"

- man 蛮 "barbarians of the South; barbarian, savage," "Southern barbarian"

- rong 戎 "weapons, armour; war, warrior; N. pr. of western tribes," "weapon; attack; war chariot; loan for tribes of the West"

- di 狄 "Northern Barbarians – "fire-dogs"," "name of a Northern tribe; low servant"

The Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus Project includes Karlgren's GSR definitions. Searching the STEDT Database finds various "a kind of" definitions for plant and animal names (e.g., you 狖 "a kind of monkey," but not one "a kind of barbarian" definition. Besides faulting Chinese for lacking a general "barbarian" term, Beckwith also faults English, which "has no words for the many foreign peoples referred to by one or another Classical Chinese word, such as 胡 hú, 夷 yí, 蠻 mán, and so on."

The third problem involves Tang Dynasty usages of fan "foreigner" and lu "prisoner", neither of which meant "barbarian." Beckwith says Tang texts used fan 番 or 蕃 "foreigner" (see shengfan and shufan above) as "perhaps the only true generic at any time in Chinese literature, was practically the opposite of the word barbarian. It meant simply 'foreign, foreigner' without any pejorative meaning." In modern usage, fan 番 means "foreigner; barbarian; aborigine". The linguist Robert Ramsey illustrates the pejorative connotations of fan.

The word "Fān" was formerly used by the Chinese almost innocently in the sense of 'aborigines' to refer to ethnic groups in South China, and Mao Zedong himself once used it in 1938 in a speech advocating equal rights for the various minority peoples. But that term has now been so systematically purged from the language that it is not to be found (at least in that meaning) even in large dictionaries, and all references to Mao's 1938 speech have excised the offending word and replaced it with a more elaborate locution, "Yao, Yi, and Yu."

The Tang Dynasty Chinese also had a derogatory term for foreigners, lu (traditional Chinese: 虜; simplified Chinese: 虏; pinyin: lǔ) "prisoner, slave, captive". Beckwith says it means something like "those miscreants who should be locked up," therefore, "The word does not even mean 'foreigner' at all, let alone 'barbarian'."

Christopher I. Beckwith's 2009 "The Barbarians" epilogue provides many references, but overlooks H. G. Creel's 1970 "The Barbarians" chapter. Creel descriptively wrote, "Who, in fact, were the barbarians? The Chinese have no single term for them. But they were all the non-Chinese, just as for the Greeks the barbarians were all the non-Greeks." Beckwith prescriptively wrote, "The Chinese, however, have still not yet borrowed Greek barbar-. There is also no single native Chinese word for 'foreigner', no matter how pejorative," which meets his strict definition of "barbarian.".

Barbarian puppet drinking game

In the Tang Dynasty houses of pleasure, where drinking games were common, small puppets in the aspect of Westerners, in a ridiculous state of drunkenness, were used in one popular permutation of the drinking game; so, in the form of blue-eyed, pointy nosed, and peak-capped barbarians, these puppets were manipulated in such a way as to occasionally fall down: then, whichever guest to whom the puppet pointed after falling was then obliged by honor to empty his cup of Chinese wine.

Japan

When Europeans came to Japan, they were called nanban (南蛮), literally Barbarians from the South, because the Portuguese ships appeared to sail from the South. The Dutch, who arrived later, were also called either nanban or kōmō (紅毛), literally meaning "Red Hair."

Pre-Columbian Americas

In Mesoamerica the Aztec civilization used the word "Chichimeca" to denominate a group of nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes that lived on the outskirts of the Triple Alliance's Empire, in the north of Modern Mexico, and whom the Aztec people saw as primitive and uncivilized. One of the meanings attributed to the word "Chichimeca" is "dog people".

The Incas of South America used the term "purum awqa" for all peoples living outside the rule of their empire (see Promaucaes).

European and American colonists frequently referred to Native Americans as "savages".

Barbarian mercenaries

The entry of "barbarians" into mercenary service in a metropole repeatedly occurred in history as a standard way in which peripheral peoples from and beyond frontier regions interact with imperial powers as part of a (semi-)foreign militarised proletariat. Examples include:

- nomadic frontier tribes serving in pre-modern China

- mainly Germanic soldiery in the armies of the declining Roman Empire

- Viking Varangian guards in imperial Byzantium

- Turkic mercenaries in the Abbasid Caliphate

- Widespread use of ethnic mercenary forces in pre-historic Mesoamerica

- Cossack units in the armies of (for example) Poland-Lithuania and of pre-Soviet Russia

- Gurkhas in the colonial and postcolonial Indian military

Early Modern period

Italians in the Renaissance often called anyone who lived outside of their country a barbarian. As an example, there is the last chapter of The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli, "Exhortatio ad Capesendam Italiam in Libertatemque a Barbaris Vinsicandam" (in English: Exhortation to take Italy and free her from the barbarians) in which he appeals to Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino to unite Italy and stop the "barbarian invasions" led by other European rulers, such as Charles VIII and Louis XII, both of France, and Ferdinand II of Aragon.

Spanish sea captain Francisco de Cuellar, who sailed with the Spanish Armada in 1588, used the term 'savage' ('salvaje') to describe the Irish people.

Marxist use of "Barbarism"

In her 1916 anti-war pamphlet The Crisis of German Social Democracy, Marxist theorist Rosa Luxemburg writes:

Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to Socialism or regression into Barbarism.

Luxemburg attributed it to Friedrich Engels, though – as shown by Michael Löwy – Engels had not used the term "Barbarism" but a less resounding formulation: If the whole of modern society is not to perish, a revolution in the mode of production and distribution must take place. The case has been made that Luxemburg had remembered a passage from The Erfurt Program, written in 1892 by Karl Kautsky, and mistakenly attributed it to Engels:

As things stand today capitalist civilization cannot continue; we must either move forward into socialism or fall back into barbarism.

Luxemburg went on to explain what she meant by "Regression into Barbarism": "A look around us at this moment [i.e., 1916 Europe] shows what the regression of bourgeois society into Barbarism means. This World War is a regression into Barbarism. The triumph of Imperialism leads to the annihilation of civilization. At first, this happens sporadically for the duration of a modern war, but then when the period of unlimited wars begins it progresses toward its inevitable consequences. Today, we face the choice exactly as Friedrich Engels foresaw it a generation ago: either the triumph of Imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or the victory of Socialism, that means the conscious active struggle of the International Proletariat against Imperialism and its method of war."