Generalized exchange is a type of social exchange in which a desired outcome that is sought by an individual is not dependent on the resources provided by that individual. It is assumed to be a fundamental social mechanism that stabilizes relations in society by unilateral resource giving in which one's giving is not necessarily reciprocated by the recipient, but by a third party. Thus, in contrast to direct or restricted exchange or reciprocity, in which parties exchange resources with each other, generalized exchange naturally involves more than two parties. Examples of generalized exchange include; matrilateral cross-cousin marriage and helping a stranded driver on a desolate road.

Reciprocity Norm

All forms of social exchange occur within structures of mutual dependence, that is, structures in which actors are mutually, or reciprocally dependent on one another for valued outcomes. A structure of mutual or reciprocal dependence is defining characteristic of all social relations based on exchange.

The mutual or reciprocal dependence can be either direct (restricted) or indirect (generalized). Both of them rest on a norm of reciprocity which provides guidance to both parties: takers are obliged to be givers. In direct dyadic exchange, the norm of reciprocity insists that takers give gifts to those who gave to them. Generalized exchange, also, insists that takers give, but to somebody else. The recipient is not defined and creates opportunities of exploitation if actors explicitly reject the guiding norm of reciprocity. The purest form of indirect, generalized exchange, is the chain-generalized form, first documented by the classical anthropologists: Lévi-Strauss (1969) and Malinowski (1922). In chain-generalized exchange, benefits flow in one direction in a circle of giving that eventually returns benefit to the giver. In direct exchange, actors instead engage in individual actions that benefit another. Reciprocal exchanges evolve gradually, as beneficial acts prompt reciprocal benefits, in a series of sequentially contingent, individual acts.

Indirect reciprocity

In indirect structures of reciprocity, each actor is depended not on a single other, as in direct forms of exchange, but on all actors who contribute to maintaining the collective system. Generalized exchange according to this logic, is a common feature of business organizations, neighborhoods, and the vast and growing network of online communities. In indirect exchanges, we observe reduced emotional tension between the partners, a credit mentality, collective orientation and high levels of solidarity and trust. Indirect reciprocity occurs when an actor who provides benefits to another is subsequently helped by a third party. Indirect reciprocity is deeply rooted in reputation processes. The indirect reciprocity requires information about the broader network (e.g., what has an actor A done for the others?). When collective organizations are large, this greater informational complexity of indirect reciprocity processes may moderate its effects. Experimental evidence shows that people respond strategically to the presence of others, cooperating at much higher levels when reputational benefits and possibilities or indirect reciprocity exist. Individuals have a tendency to reward givers and penalize non-givers - which is often explained from the perspectives of prosocial behavior and norm enforcement. But another explanation may lie in reputational concerns. In other words, because so much of human behavior is based on the reputational advantages and opportunities, evolutionary theorists posit that the foundations of human morality are rooted in indirect reciprocity and reputational processes.

In generalized exchange, one actor gives benefits to another, and receives from another, but not from the same actor. We have a context of a chain-generalized system of exchange where A, B, and C are the connected parties. They may also be a part of a larger, more diffused network, with no defined structure. According to Takahashi (2000), this is called "pure generalized" exchange. In this form, there is no fixed structure of giving. A might give to B on one occasion and to C on a different occasion. The structure of indirect reciprocity affects the solidarity in comparison with forms of exchange with direct reciprocity.

Direct (Restricted) reciprocity

In forms of exchange with direct reciprocity, two actors exchange resources with one another. This means, A provides value to B, and B to A. B's reciprocation of A's giving is direct and each actor's outcomes depend solely on the behavior of another actor or actors. Direct structures of reciprocity produce exchanges which have different consequences for trust and solidarity. Direct exchanges are characterized by high emotional tension and lack of trust – quid pro quo – self-interested actors who often engage in conflicts over fairness of exchanges and low levels of trust.

An American sociologist Richard Marc Emerson (1981) further distinguished between two forms of transactions in direct exchange relations: negotiated and reciprocal. There exists a clear distinction between negotiated and reciprocal forms of direct exchange. Along these lines, Yamagishi and Cook(1993) and Takahashi(2000) note that emphasis on collective aspects of generalized exchange neglects elements such as: the high risk of the structure, the potential for those who fail to give to disrupt the entire system, and the difficulty of establishing a structure of stable giving without initial levels of high trust or established norms.

Variations in Direct Reciprocity

Direct Negotiated Exchange

American sociologists: Karen S. Cook, Richard M. Emerson, Toshio Yamagishi, Mary R. Gillmore, Samuel B. Bacharach, and Edward J. Lawler all study negotiated transactions.

In such exchange, actors together arrange and negotiate the terms of an agreement that benefits both parties, either equally or unequally. This is a joint decision process, an explicit bargaining. Both sides of the exchange are agreed upon at the same time, and the benefits for both exchange partners are easily identified as paired contributions that form a discrete transaction. There agreements are strictly binding and produce the benefits agreed upon. Most economic exchanges (excluding fixed-price trades) as well as many other social exchanges fall under this category.

Direct Reciprocal Exchange

In such exchange, actors engage in actions that benefit one another. Actors' contributions to the exchange are not ex-ante negotiated. Actors initiate exchanges without knowing whether their actions will be reciprocated ex-post. Such contributions are performed separately and are not known to the counterparties. Behaviors can be advice-giving, assistance, help, and are not subject to negotiation. Moreover, there is no knowledge whether or when or to what extent the other will reciprocate. Reciprocal transactions are distinct from pure economic exchanges and are typical in many interpersonal relationships where norms curtail the extent of explicit bargaining.

Structural Relations

Negotiated and reciprocal exchanges create different structural relations between actors' behaviors and between their outcomes. Both forms of transactions alter the risk inherent in relations of mutual dependence, but in different ways.

- Reciprocal exchange - decisions are made individually by actors; flow of benefits is unilateral.

- Negotiated exchange - decisions are made jointly and are strictly binding, they cannot be violated; flow of benefits is bilateral.

- Generalized exchange - flow of benefits is unilateral

In theory, all three forms of exchange – indirect, direct negotiated, and direct reciprocal – differ from one another on a set of dimensions that potentially affect the development of social solidarity. These dimensions comprise the structure of reciprocity in social exchange. Theory argues that while all forms of exchange are characterized by some type of reciprocity, the structure of reciprocity varies on two key dimensions that affect the social solidarity or integrative bonds that develop between actors:

- Whether benefits are reciprocated directly or indirectly, two additional structural differences emerge:

- Corresponds to the basic distinction between direct (restricted) and indirect (generalized) forms of exchange discussed above. Direct vs indirect reciprocity also implies two related structural differences: whether exchange is dyadic (2-party) or collective (3+), and whether or not actors are depended on the actions of a single other actor or multiple actors for valued resources.

- Whether benefits can flow unilaterally or only bilaterally.

- Unilateral – each actor’s outcomes are contingent solely on another’s individual actions, and actors can initiate exchanges that are not reciprocated (and vice versa). Timing of reciprocity can be delayed in both reciprocal and generalized exchange.

- When exchanges are negotiated, we have joint action effects, meaning, flow of benefits are always bilateral and each transaction produces an agreement that provides benefits (equal or unequal) for both actors.

Incentives and motivations

Structure of reciprocity can affect exchange in a more fundamental way, through its implications on actors’ incentives. Generalized reciprocity is a way of "organizing" an ongoing process of "interlocked behaviors" where one person’s behavior depends on another’s, whose is also depended on another’s, the process forming a chain reaction. For generalized exchange to emerge, individuals must overcome the temptation to receive without contributing and instead in engage in sharing (cooperative) behavior. Once the sharing begins, the overall collective good can increase as more individuals contribute more goods (with high jointness of supply). As group size grows in an organization, individual information preferences are more likely to be met through diversity.

Social Psychological Incentives

Individuals should be encouraged to make altruistic contribution to a collective good for generalized exchange to emerge. Empirical studies show that altruistic behavior is a natural aspect of social interaction. Individuals donate blood and organs at some personal cost with no direct benefits. When contributions are also rewarded, then contributing and cooperation becomes more attractive regardless of decisions of others. There are incentives to motivate sharing knowledge and helping others in organizations such as, formal participation quotas, making helping and giving an enforceable requirement with guaranteed rewards. Such incentives, do not specify who helps who – that is more discretionary. Individuals are free to choose who to help, and these choices can vary from helping only those that have helped an individual in the past (direct reciprocity), or to help those that have helped others and not helping those that have not helped. Incentives have been successful as an economic solution to free-riding, because they offer additional motivations that make cooperation rational.

Social Approval

Individuals may gain some intrinsic satisfaction from the popularity of their own contribution in the form of psychological efficacy, causing an individual to want to share more in the future. Additionally, individuals may participate in giving social approval by rating the popularity of other's contributions. This makes giving and receiving social approval to have an influence on behavior. Individuals may cooperate (or share) because they care about receiving social approval and/or because they want to give social approval to others' contributions. Social approval is a combination of these two processes.

Rewarding Reputation

Reputation is regarded as an incentive in generalized reciprocity. Evolutionary theorists Nowak and Sigmund (1998) regard reputation a person’s image. This, in organizations, is named as "professional image", namely, others’ perceptions of individuals within organizations – but with a focus on helpfulness. The same authors also show in their simulation study that strategy of rewarding reputation produces an evolutionary stable system of generalized reciprocity. Same idea is echoed by economic experiments where the rewarding of reputation is shown to yield generalized reciprocity. Individuals with reputations for helpfulness are more likely to get helped in contrast to those individuals without such reputation. Real-life examples show that in situations where reputations for helpfulness are rewarded, individuals are prone to engaging in helping others so that they will in return be rewarded and helped in the future. Incentive here is to be helped in the future – which is why individuals engage in building reputation. Experimental research on rewarding reputation also shows that reputations in organizations too are built with such incentives, and through consistent demonstration of "distinctive and salient behaviors on repeated occasions, or over time". Consequences for such actions are the following: good reputation results in more autonomy, power, and career success.

Rewarding reputation is more time contingent. It is taxing for individuals to keep track of what everyone else does and monitor whose rate of helping is higher. This makes rewarding reputation tied to the recency of helpfulness. Individuals are found to make decisions based on recent reputation of others rather than their long-term reputation. The reward system of reciprocity is based on "what have you don’t for us lately?!" and the less recent one’s deeds are, the less likely it is for these individuals to receive help in return.

To encourage reciprocity and incentivize individuals to engage in such prosocial behavior, organizations are shown to enforce norms of asking for help, giving help, and reciprocating help by organizing meetings and informal practices. Supervisors are also encouraged to use symbolic or financial rewards to incentivize helping. Google for example, uses a peer-to-peer bonus system that empowers employees to express gratitude and reward helpful behavior with token payments. Additionally, they use paying it forward incentive – meaning, those individuals that receive such bonuses, are given additional funds that may only be paid forward to recognize a third employee. To encourage knowledge exchange, large organizations employ knowledge-sharing communities in which they post and respond to requests for help around work-related problems.

Reputational concerns were found to be the driving force behind the effect of observability. Moreover, this effect was substantially stronger in settings where individuals were more likely to have future interactions with those who observed them and when participation was framed as a public good.

Observational Cooperation

Individuals will conditionally cooperate based on what they believe others are doing in a public goods situation. From a game-theoretical perspective, there is no strategic advantage to matching one's cooperation level to the rest of the group when others are already cooperating at a relatively high level.

Future-oriented behavior

Future-oriented behavior deals with the tendency for individuals to modify their behavior based on what they believe will happen in the future. Such behavior shares a similar logic to the game-theoretical approach to conditional cooperation. Individuals plan strategically their actions in terms of looking forward to future interactions.

Reactive Behavior

In reactive behavior, individuals tend to orient themselves towards the average behavior of other group members. Such behavior is closely tied to the principle of reciprocity. When individuals can see the overall cooperation level of the participants, they can stimulate a normative response to reciprocate by cooperating as well. In addition, when contributions are observable, individuals can also signal their commitment by making small contributions without taking too much risk at once. Observing cooperative behavior also imposes obligation on an individual to also cooperate. Decisions to cooperate become more impersonal. Individuals can experience at least a minimal amount of satisfaction from being a cooperator because they feel like they are part of a larger group and organization.

Social mechanism

Exchange, generalized or otherwise, is an inherently social construct. Social dynamics set the stage for an exchange to occur, between whom the exchange occurs, and what will happen after the exchange occurs. For example, exchange has been shown to have effects on an individual's reputation and standing.

Some have conceived of indirect reciprocity as being a result of direct reciprocity that is observed, as direct exchanges that are not observed by others cannot possibly increase the standing of an individual to an entire group except through piecemeal methods such as gossip. Through observation, it becomes clearer to a group who gives or reciprocates and who does not; in this way good actions can be rewarded or encouraged, and bad actions can be sanctioned through refusal to give.

Exchange is also a human process in the sense that it is not always carried out or perceived correctly. Individuals in groups can hold faulty perceptions of other actors which will lead them to take sanctioning action; this can also in turn lead to a lowering of the standing of that individual, if the group perceives the receiving actor undeserving of sanction. In a similar way, sometimes individuals may intend on taking a certain action and failing to do so either through human error (e.g. forgetfulness) or due to circumstances that prevent them from doing so. For these reasons, there will always be a certain degree of error in the way that exchange systems work.

Social solidarity

One hypothesized outcome of exchange processes is social solidarity. Through continued exchange between many different members of a group, and the continuous attempt to sanction and eliminate self-serving behavior, a group can become tightly-connected to the point that an individual identifies with the group. This identification could then lead an individual to protect or aid the group even at one's own cost or without any promise of benefit in return.

The idea of why society needs exchanges in the first place could date back both anthropologically and sociologically.

Sociological Perspective

Sociologists use the term of solidarity to explain exchanges. Emile Durkheim differentiates solidarity into mechanical and organic solidarity according to the type of the society.

Mechanical solidarity is associated with pre-modern society, where individuals are homogeneous and the cohesion arises mainly from shared values, lifestyles and work. Kinship connects individuals inside the society hence the exchange exists solely for survival purpose because of the low level of role specialization. This makes the solidarity mechanical as the exchange appears only when someone needs others, which may fall into exchange theory, with reciprocity in the form of status or reputation, as well as generalized exchange theory, where, out of expectation from the homogeneous group, reciprocity starts from the recipient helping a third and ends as the cycle is closed. That is to say, exchange theory argues that in a primitive society, reciprocity may be accompanied by an enhanced status or reputation while the sole intentionality for such exchange is survival. Generalized exchange theory believes that there is a social consensus out of commonly shared value or lifestyle that exchange does not require an immediate reciprocity but promise another activity, which, after several iterations, closes the cycle. Another important presumption in mechanical solidarity is the low level of role specialization where an individual may ask a random one, not necessary an expert, for help and this random one is capable of providing expected service.

Organic solidarity in modern society differs from the above-mentioned mechanical one. Modern society steps out of small and kinship-based town and integrates heterogeneous individuals that vary in their education, social class, religions, nations and races. Individuals stay distant from others psychologically and sociologically but meanwhile depend upon each other for their own well-being. The generalized exchange is hence more complicated as a result of longer chain in the cycle and perhaps temporal expansion. Different from a primitive society with a low level of role specialization, modern society is endowed with high specialization that emphasizes the searching process of the correct one when an exchange relation starts. When this searching fails finding a legitimate counterpart, this emerged exchange relation may die before birth. Therefore, the mechanism of organic solidarity is more complicated as the emergence, transmission, driving mechanism and the end point need careful reviews.

Anthropological Perspective

Anthropologists, quite different from sociologists, study the solidarity from the structural functionalism. While sociologists view individuals engaged in exchange due to the social factors, anthropologists, such as Levi-Strauss, believe the exchange is more of the solidarity in maintaining a well-functioned society than that for socially constrained individuals’ own needs. The society is believed to be an organism and all parts function together for the stability of the organism. Individuals work for the society and, reciprocally, they receive, say, philanthropic, materialistic, and social return from the society. It is similar to the modern society described by sociologists above, but the point here is that the solidarity is the cause of individual activities, which means individuals’ activities are dominated by the idea of solidarity, while sociologists’ modern society reaches solidarity as a result of individual’s self-oriented activities, where the solidarity is observed after selfish individuals focus on their own interests.

However, Malinowski studies the kula ring exchange on some island and concludes that individuals participate in the ritual or ceremony out of their own needs, where they feel satisfied as a part of the society. This could also be interpreted religiously as individuals hold the society above their social roles hence they actively become involved in the ceremony and reciprocally benefit psychologically and socially from being a part of the holiness, which, in a way, agrees with the idea of solidarity as the cause.

Social dilemmas

The unilateral character of generalized exchange that lacks one-to-one correspondence between what two parties directly give to and take from one another, distinguishes it from direct or restricted exchange. Ekeh (1974), a pioneer scholar in exchange theory, argues that generalized exchange is more powerful than restricted forms of exchange in generating morality, promoting mutual trust and solidarity among the participants. This view, however, was found to be too optimistic or problematic by later scholars, given that it ignores the social dilemmas created by the exchange structure. Because generalized exchange paves the way for exploitation by rational self-interested members, thus a free rider problem. This social dilemma needs to be resolved for generalized exchange systems to emerge and survive.

Free rider problem

Despite the risk of free riding, early exchange theorists proposed several explanations to why such exchange systems exist. Among others, altruistic motivation of members, existence of collective norms and incentives that regulates the behaviour of returning resources to any member, are most discussed ideas. However, these approaches do not guarantee the maintenance of exchange system, since compliance is facilitated by monitoring which does not exist in most cases. Subsequent social theorists proposed more feasible solutions that prevent free rider problem in generalized exchange systems. These solutions are described below by using the terminology adapted from Takahashi (2000).

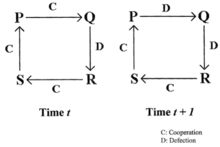

Downward Tit-for-tat strategy

Tit-for-Tat strategy was originally introduced in game theory in order to provide solution to Prisoner’s dilemma by promoting mutual cooperation between two actors. This strategy has been adapted to bilateral and network relations, and in both cases the strategy works only in restricted – rather than generalized – exchange, because it involves bilateral resource giving in either situation. In an effort to propose a strategy to solve the social dilemma aspect of generalized exchange, Yamagishi and Cook (1993) analyzed the effect of network structures on group members’ decisions. Relying on Ekeh’s (1974) approach, they distinguish two forms of generalized exchange as "group-generalized" and "network-generalized". In the first type, group members pool their resources and then receive benefits that are generated by pooling. In the second, each member provides resources to another member in the network who does not return benefits directly to the provider, but the provider receives benefits from some other member in the network. They basically claim that group-generalized exchange involves free rider problem as it is rational for any member to receive resources from pool without contributing. On the other hand, network-generalized exchange limits the occurrence of this problem as it is easier to detect free riding member and punish him/her by withholding resources until s/he starts to give. The laboratory experiments supported these predictions and they showed that network-generalized exchange promotes a higher level of participation (or cooperation) that group-generalized exchange structure. They also show that trust is an important factor for the survival of both systems and has a stronger effect on cooperation in the network-generalized structure than in the group-generalized structure.

In another study, biologists Boyd and Richerson (1989) presented a model of evolution of indirect reciprocity and supported the idea that downward tit-for-tat strategy helps sustaining network-generalized exchange structures. They also claim that as the group size increases, positive effect of this strategy on the possibility of cooperation reduces. In summary, these studies show that for a generalized exchange system to emerge and survive, a fixed form of network that consists of unidirectional paths is required. When this is available, adapting downward tit-for-tat strategy is profitable for all members and free riding is not possible. However, according to Takahashi (2000), the requirement of a fixed network structure is a major limitation since many of real world generalized exchange systems do not represent a simple closed chain of resource giving.

Pure-generalized exchange

Takahashi and Yamagishi proposed pure-generalized exchange as a situation where there is no fixed structure. It is regarded as more general, flexible and less restricted compared to previous models. In essence, pure-generalized exchange is network-generalized exchange with a choice of recipients, where each actor gives resources to recipient(s) that s/he chooses unilaterally. However, this model also comes with a limitation; the necessity of a criterium that represents a collective sense of fairness among the members. By easing the limitations caused by the models described above, Takahashi (2000) proposed a more general solution to the free rider problem. This new model is summarized below.

Fairness-based selective giving in pure-generalized exchange

The new model proposed by Takahashi (2000), solved the free rider problem in generalized exchange by imposing particular social structures as little as possible. He adapted pure-generalized exchange situation with a novel strategy; fairness-based selective giving. In this strategy, actors select recipients whose behaviors satisfy their own criteria of fairness which would make pure-generalized exchange possible. He showed that this argument can hold in two evolutionary experiments, in particular, pure-generalized exchange can emerge even in a society in which members have different standards of fairness. Thus, altruism and a collective sense of fairness are no longer required in such a setting. Why self-interested actors give resources unilaterally has been interpreted with the possibility that this action increases profits by participation in exchange.

Contexts

Exchange processes have been studied in a variety of empirical contexts. Much of the beginning of generalized exchange work revolved around tribal settings. For example, Malinowski’s Trobriand Island research serves as a foundational work for the study of exchange. The classic example of the Kula ring showed a system of exchange formed cyclically, where a giver would receive after a product given had gone through a full circle of receivers. Similar tribal research includes the inhabitants of Groote Eylandt, and matrilineal cross-cousin marriages.

These early studies have provoked the study of reciprocity and exchange in modern settings as well. For example, with technology comes exchange through information sharing in large, anonymous online communities of software developers. Even within academia, exchange has been studied through prosocial behaviors in a group of MBA students. Takahashi (2000) provided several places where generalized exchange can be observed in real life. Aiding a stranded driver alongside a road speaks to a societal-level feeling of duty to help others based on past experience or future expectation of needing help. Such a duty may also serve as the motivation for donating blood to unknown or indiscriminate receivers. Academically, the reviewers of journal articles also do so without payment in order to contribute to the system of publication and the knowledge that others will do so, or have already done so, for their papers. In addition to qualitative and ethnographic research, scholars have also studied generalized exchange through targeted lab experiments as well as programmed simulations. Generalized exchange has further studied through real life experiences, such as participation in public good conservation programs when one is recognized for doing so as opposed to when one’s name remains anonymous.

Generalized exchange structures can be statistically represented by blockmodels, which is an effective method for characterizing the pattern of multiple type and asymmetric social interactions in complex networks.