Greek love is a term originally used by classicists to describe the primarily homoerotic customs, practices, and attitudes of the ancient Greeks. It was frequently used as a euphemism for both homosexuality and pederasty. The phrase is a product of the enormous impact of the reception of classical Greek culture on historical attitudes toward sexuality, and its influence on art and various intellectual movements.

'Greece' as the historical memory of a treasured past was romanticised and idealised as a time and a culture when love between males was not only tolerated but actually encouraged, and expressed as the high ideal of same-sex camaraderie. ... If tolerance and approval of male homosexuality had happened once—and in a culture so much admired and imitated by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—might it not be possible to replicate in modernity the antique homeland of the non-heteronormative?

Following the work of sexuality theorist Michel Foucault, the validity of an ancient Greek model for modern gay culture has been questioned. In his essay "Greek Love", Alastair Blanshard sees "Greek love" as "one of the defining and divisive issues in the homosexual rights movement.

Historic terms

As a phrase in Modern English and other modern European languages, "Greek love" refers to various (mostly homoerotic) practices as part of the Hellenic heritage reinterpreted by adherents such as Lytton Strachey; quotation marks are often placed on either or both words ("Greek" love, Greek "love", or "Greek love") to indicate that usage of the phrase is determined by context. It often serves as a "coded phrase" for pederasty, or to "sanitize" homosexual desire in historical contexts where it was considered unacceptable.

The German term griechische Liebe ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with socratische Liebe ("Socratic love") and platonische Liebe ("Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. Ancient Greece became a positive reference point by which homosexual men of a certain class and education could engage in discourse that might otherwise be taboo. In the early Modern period, a disjuncture was carefully maintained between idealized male eros in the classical tradition, which was treated with reverence, and sodomy, which was a term of contempt.

Ancient Greek background

In his classic study Greek Homosexuality, Kenneth Dover states that the English nouns "a homosexual" and "a heterosexual" have no equivalent in the ancient Greek language. According to Dover, there was no concept in ancient Greece equivalent to the modern conception of "sexual preference"; it was assumed that a person could have both hetero- and homosexual responses at different times. Evidence for same-sex attractions and behaviors is more abundant for men than for women. Both romantic love and sexual passion between men were often considered normal, and under some circumstances healthy or admirable. The most common male-male relationship was paiderasteia, a socially-acknowledged institution in which a mature male (erastēs, the active lover) bonded with or mentored a teen-aged youth (eromenos, the passive lover, or pais, "boy" understood as an endearment and not necessarily a category of age ). Martin Litchfield West views Greek pederasty as "a substitute for heterosexual love, free contacts between the sexes being restricted by society".

Greek art and literature portray these relationships as sometimes erotic or sexual, or sometimes idealized, educational, non-consummated, or non-sexual. A distinctive feature of Greek male-male eros was its occurrence within a military setting, as with the Theban Band, though the extent to which homosexual bonds played a military role has been questioned.

Some Greek myths have been interpreted as reflecting the custom of paiderasteia, most notably the myth of Zeus kidnapping Ganymede to become his cupbearer in the Olympian symposium. The death of Hyacinthus is also frequently referenced as a pederastic myth.

The main Greek literary sources for Greek homosexuality are lyric poetry, Athenian comedy, the works of Plato and Xenophon, and courtroom speeches from Athens. Vase paintings from the 500s and 400s BCE depict courtship and sex between males.

Ancient Rome

In Latin, mos Graeciae or mos Graecorum ("Greek custom" or "the way of the Greeks") refers to a variety of behaviors the ancient Romans regarded as Greek, including but not confined to sexual practice. Homosexual behaviors at Rome were acceptable only within an inherently unequal relationship; male Roman citizens retained their masculinity as long as they took the active, penetrating role, and the appropriate male sexual partner was a prostitute or slave, who would nearly always be non-Roman. In Archaic and classical Greece, paiderasteia had been a formal social relationship between freeborn males; taken out of context and refashioned as the luxury product of a conquered people, pederasty came to express roles based on domination and exploitation. Slaves often were given, and prostitutes sometimes assumed, Greek names regardless of their ethnic origin; the boys (pueri) to whom the poet Martial is attracted have Greek names. The use of slaves defined Roman pederasty; sexual practices were "somehow 'Greek'" when they were directed at "freeborn boys openly courted in accordance with the Hellenic tradition of pederasty".

Effeminacy or a lack of discipline in managing one's sexual attraction to another male threatened a man's "Roman-ness" and thus might be disparaged as "Eastern" or "Greek". Fears that Greek models might "corrupt" traditional Roman social codes (the mos maiorum) seem to have prompted a vaguely documented law (Lex Scantinia) that attempted to regulate aspects of homosexual relationships between freeborn males and to protect Roman youth from older men emulating Greek customs of pederasty.

By the close of the 2nd century BCE, however, the elevation of Greek literature and art as models of expression caused homoeroticism to be regarded as urbane and sophisticated. The consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus was among a circle of poets who made short, light Hellenistic poems fashionable in the late Republic. One of his few surviving fragments is a poem of desire addressed to a male with a Greek name, signaling the new aesthetic in Roman culture. The Hellenization of elite culture influenced sexual attitudes among "avant-garde, philhellenic Romans", as distinguished from sexual orientation or behavior, and came to fruition in the "new poetry" of the 50s BCE. The poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus, written in forms adapted from Greek meters, include several expressing desire for a freeborn youth explicitly named "Youth" (Iuventius). His Latin name and free-born status subvert pederastic tradition at Rome. Catullus's poems are more often addressed to a woman.

The literary ideal celebrated by Catullus stands in contrast to the practice of elite Romans who kept a puer delicatus ("exquisite boy") as a form of high-status sexual consumption, a practice that continued well into the Imperial era. The puer delicatus was a slave chosen from the pages who served in a high-ranking household. He was selected for his good looks and grace to serve at his master's side, where he is often depicted in art. Among his duties, at a convivium he would enact the Greek mythological role of Ganymede, the Trojan youth abducted by Zeus to serve as a divine cupbearer. Attacks on emperors such as Nero and Elagabalus, whose young male partners accompanied them in public for official ceremonies, criticized the perceived "Greekness" of male-male sexuality. "Greek love", or the cultural model of Greek pederasty in ancient Rome, is a "topos or literary game" that "never stops being Greek in the Roman imagination", an erotic pose to be distinguished from the varieties of real-world sexuality among individuals. Vout sees the views of Williams and MacMullen as opposite extremes on the subject.

Renaissance

Male same-sex relationships of the kind portrayed by the "Greek love" ideal were increasingly disallowed within the Judaeo-Christian traditions of western society. In the postclassical period, love poetry addressed by males to other males has been in general taboo. According to Reeser's book "Setting Plato Straight", it was the Renaissance that shifted the idea of love in Plato's sense to what we now refer to as "Platonic love"—as asexual and heterosexual.

In 1469, the Italian Neoplatonist Marsilio Ficino reintroduced Plato's Symposium to western culture with his Latin translation titled De Amore ("On Love"). Ficino is "perhaps the most important Platonic commentator and teacher in the Renaissance". The Symposium became the most important text for conceptions of love in general during the Renaissance. In his commentary on Plato, Ficino interprets amor platonicus ("Platonic love") and amor socraticus ("Socratic love") allegorically as idealized male love, in keeping with the Church doctrine of his time. Ficino's interpretation of the Symposium influenced a philosophical view that the pursuit of knowledge, particularly self-knowledge, required the sublimation of sexual desire. Ficino thus began the long historical process of suppressing the homoeroticism of in particular, the dialogue Charmides "threatens to expose the carnal nature of Greek love" which Ficino sought to minimize.

For Ficino, "Platonic love" was a bond between two men that fosters a shared emotional and intellectual life, as distinguished from the "Greek love" practiced historically as the erastes/eromenos relationship. Ficino thus points toward the modern usage of "Platonic love" to mean love without sexuality. In his commentary to the Symposium, Ficino carefully separates the act of sodomy, which he condemned, and praises Socratic love as the highest form of friendship. Ficino maintained that men could use each other's beauty and friendship to discover the greatest good, that is, God, and thus Christianized idealized male love as expressed by Socrates.

During the Renaissance, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo used Plato's philosophy as inspiration for some of their greatest works. The "rediscovery" of classical antiquity was perceived as a liberating experience, and Greek love as an ideal after a Platonic model. Michelangelo presented himself to the public as a Platonic lover of men, combining Catholic orthodoxy and pagan enthusiasm in his portrayal of the male form, most notably the David, but his great-nephew edited his poems to diminish references to his love for Tommaso Cavalieri.

By contrast, the French Renaissance essayist Montaigne, whose view of love and friendship was humanist and rationalist, rejected "Greek love" as a model in his essay "De l'amitié" ("On Friendship"); it did not accord with the social needs of his own time, he wrote, because it involved "a necessary disparity in age and such a difference in the lovers' functions". Because Montaigne saw friendship as a relationship between equals in the context of political liberty, this inequality diminished the value of Greek love. The physical beauty and sexual attraction inherent in the Greek model for Montaigne were not necessary conditions of friendship, and he dismisses homosexual relations, which he refers to as licence grecque, as socially repulsive. Although the wholesale importation of a Greek model would be socially improper, licence grecque seems to refer only to licentious homosexual conduct, in contrast to the moderate behavior between men in the perfect friendship. When Montaigne chooses to introduce his essay on friendship with recourse to the Greek model, "homosexuality's role as trope is more important than its status as actual male-male desire or act ... licence grecque becomes an aesthetic device to frame the center."

Neoclassicism

German Hellenism

The German term griechische Liebe ("Greek love") appears in German literature between 1750 and 1850, along with socratische Liebe ("Socratic love") and platonische Liebe ("Platonic love") in reference to male-male attractions. The work of the German art historian Johann Winckelmann was a major influence on the formation of classical ideals in the 18th century, and is also a frequent starting point for histories of gay German literature. Winckelmann observed the inherent homoeroticism of Greek art, though he felt he had to leave much of this perception implicit: "I should have been able to say more if I had written for the Greeks, and not in a modern tongue, which imposed on me certain restrictions." His own homosexuality influenced his response to Greek art and often tended toward the rhapsodic: "from admiration I pass to ecstasy ...," he wrote of the Apollo Belvedere, "I am transported to Delos and the sacred groves of Lycia—places Apollo honoured with his presence—and the statue seems to come alive like the beautiful creation of Pygmalion." Although now regarded as "ahistorical and utopian", his approach to art history provided a "body" and "set of tropes" for Greek love, "a semantics surrounding Greek love that ... feeds into the related eighteenth-century discourses on friendship and love".

Winckelmann inspired German poets in the latter 18th and throughout the 19th century, including Goethe, who pointed to Winckelmann's glorification of the nude male youth in ancient Greek sculpture as central to a new aesthetics of the time, and for whom Winckelmann himself was a model of Greek love as a superior form of friendship. While Winckelmann did not invent the euphemism "Greek love" for homosexuality, he has been characterized as an "intellectual midwife" for the Greek model as an aesthetic and philosophical ideal that shaped the 18th-century homosocial "cult of friendship".

German 18th-century works from the "Greek love" milieu of classical studies include the academic essays of Christoph Meiners and Alexander von Humboldt, the parodic poem "Juno and Ganymede" by Christoph Martin Wieland, and A Year in Arcadia: Kyllenion (1805), a novel about an explicitly male-male love affair in a Greek setting by Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.

French Neoclassicism

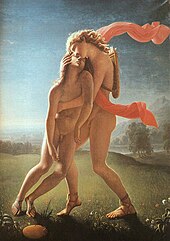

Neoclassical works of art often represented ancient society and an idealized form of "Greek love". Jacques-Louis David's Death of Socrates is meant to be a "Greek" painting, imbued with an appreciation of "Greek love", a tribute and documentation of leisured, disinterested, masculine fellowship.

English Romanticism

The concept of Greek love was important to two of the most significant poets of English Romanticism, Byron and Shelley. During the Regency era in which they lived, homosexuality was looked upon with increased disfavour and denounced by many in the general public, in line with the encroachment of Victorian values into the public mainstream. The terms "homosexual" and "gay" were not used during this period, but "Greek love" among Byron's contemporaries became a way to conceptualize homosexuality, otherwise taboo, within the precedents of a highly esteemed classical past. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham, for instance, appealed to social models of classical antiquity, such as the homoerotic bonds of the Theban Band and pederasty, to demonstrate how these relationships did not inherently erode heterosexual marriages or the family structure.

The high regard for classical antiquity in the 18th century caused some adjustment in homophobic attitudes on the Continent. In Germany, the prestige of classical philology led eventually to more honest translations and essays that examined the homoeroticism of Greek culture, particularly pederasty, in the context of scholarly inquiry rather than moral condemnation. An English archbishop penned what may be the most effusive account of Greek pederasty available in English at the time, duly noted by Byron on the "List of Historical Writers Whose Works I Have Perused" that he drew up at age 19.

Plato was little read in Byron's time, in contrast to the later Victorian era when translations of the Symposium and Phaedrus would have been the most likely way for a young student to learn about Greek sexuality. The one English translation of the Symposium, published in two parts in 1761 and 1767, was an ambitious undertaking by the scholar Floyer Sydenham, who nevertheless was at pains to suppress its homoeroticism: Sydenham regularly translated the word eromenos as "mistress", and "boy" often becomes "maiden" or "woman". At the same time, the classical curriculum in English schools passed over works of history and philosophy in favor of Latin and Greek poetry that often dealt with erotic themes. In describing homoerotic aspects of Byron's life and work, Louis Crompton uses the umbrella term "Greek love" to cover literary and cultural models of homosexuality from classical antiquity as a whole, both Greek and Roman, as received by intellectuals, artists, and moralists of the time. To those such as Byron who were steeped in classical literature, the phrase "Greek love" evoked pederastic myths such as Ganymede and Hyacinthus, as well as historical figures such as the political martyrs Harmodius and Aristogeiton, and Hadrian's beloved Antinous; Byron refers to all these stories in his writings. He was even more familiar with the classical tradition of male love in Latin literature, and quoted or translated homoerotic passages from Catullus, Horace, Virgil, and Petronius, whose name "was a byword for homosexuality in the eighteenth century". In Byron's circle at Cambridge, "Horatian" was a code word for "bisexual". In correspondence, Byron and his friends resorted to the code of classical allusions, in one exchange referring with elaborate puns to "Hyacinths" who might be struck by coits, as the mythological Hyacinthus was accidentally felled while throwing the discus with Apollo.

Shelley complained that contemporary reticence about homosexuality kept modern readers without a knowledge of the original languages from understanding a vital part of ancient Greek life. His poetry was influenced by the "androgynous male beauty" represented in Winckelmann's art history. Shelley wrote his Discourse on the Manners of the Antient Greeks Relative to the Subject of Love on the Greek conception of love in 1818 during his first summer in Italy, concurrently with his translation of Plato's Symposium. Shelley was the first major English writer to analyse Platonic homosexuality, although neither work was published during his lifetime. His translation of the Symposium did not appear in complete form until 1910. Shelley asserts that Greek love arose from the circumstances of Greek households, in which women were not educated and not treated as equals, and thus not suitable objects of ideal love. Although Shelley recognised the homosexual nature of the love relationships between males in ancient Greece, he argued that homosexual lovers often engaged in no behaviour of a sexual nature, and that Greek love was based on the intellectual component, in which one seeks a complementary beloved. He maintains that the immorality of the homosexual acts are on par with the immorality of contemporary prostitution, and contrasts the pure version of Greek love with the later licentiousness found in Roman culture. Shelley cites Shakespeare's sonnets as another expression of the same sentiments, and ultimately argues that they are chaste and platonic in nature.

Victorian era

Throughout the 19th century, upper-class men of same-sex orientation or sympathies regarded "Greek love", often used as a euphemism for the ancient pederastic relationship between a man and a youth, as a "legitimating ideal": "the prestige of Greece among educated middle-class Victorians ... was so massive that invocations of Hellenism could cast a veil of respectability over even a hitherto unmentionable vice or crime." Homosexuality emerged as a category of thought during the Victorian era in relation to classical studies and "manly" nationalism; the discourse of "Greek love" during this time generally excluded women's sexuality. Late Victorian writers such as Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde, and John Addington Symonds saw in "Greek love" a way to introduce individuality and diversity within their own civilization. Pater's short story "Apollo in Picardy" is set at a fictional monastery where a pagan stranger named Apollyon causes the death of the young novice Hyacinth; the monastery "maps Greek love" as the site of a potential "homoerotic community" within Anglo-Catholicism. Others who addressed the subject of Greek love in letters, essays, and poetry include Arthur Henry Hallam.

The efforts among aesthetes and intellectuals to legitimate various forms of homosexual behaviors and attitudes by virtue of a Hellenic model were not without opposition. The 1877 essay "The Greek Spirit in Modern Literature" by Richard St. John Tyrwhitt warned against the perceived immorality of this agenda. Tyrwhitt, who was a vigorous supporter of studying Greek, characterized the Hellenism of his day as "the total denial of any moral restraint on any human impulses", and outlined what he saw as the proper scope of Greek influence on the education of young men. Tyrwhitt and other critics attacked by name several scholars and writers who had tried to use Plato to support an early gay-rights agenda and whose careers were subsequently damaged by their association with "Greek love".

Symonds and Greek ethics

In 1873, the poet and literary critic John Addington Symonds wrote A Problem in Greek Ethics, a work of what could later be called "gay history", inspired by the poetry of Walt Whitman. The work, "perhaps the most exhaustive eulogy of Greek love", remained unpublished for a decade, and then was printed at first only in a limited edition for private distribution. Symonds's approach throughout most of the essay is primarily philological. He treats "Greek love" as central to Greek "aesthetic morality". Aware of the taboo nature of his subject matter, Symonds referred obliquely to pederasty as "that unmentionable custom" in a letter to a prospective reader of the book, but defined "Greek love" in the essay itself as "a passionate and enthusiastic attachment subsisting between man and youth, recognised by society and protected by opinion, which, though it was not free from sensuality, did not degenerate into mere licentiousness".

Symonds studied classics under Benjamin Jowett at Balliol College, Oxford, and later worked with Jowett on an English translation of Plato's Symposium. When Jowett was critical of Symonds' opinions on sexuality, Dowling notes that Jowett, in his lectures and introductions, discussed love between men and women when Plato himself had been talking about the Greek love for boys. Symonds asserted that "Greek love was for Plato no 'figure of speech', but a present and poignant reality. Greek love is for modern studies of Plato no 'figure of speech' and no anachronism, but a present poignant reality." Symonds struggled against the desexualization of "Platonic love", and sought to debunk the association of effeminacy with homosexuality by advocating a Spartan-inspired view of male love as contributing to military and political bonds. When Symonds was falsely accused of corrupting choirboys, Jowett supported him, despite his own equivocal views of the relation of Hellenism to contemporary legal and social issues that affected homosexuals.

Symonds also translated classical poetry on homoerotic themes, and wrote poems drawing on ancient Greek imagery and language such as Eudiades, which has been called "the most famous of his homoerotic poems": "The metaphors are Greek, the tone Arcadian and the emotions a bit sentimental for present-day readers."

One of the ways in which Symonds and Whitman expressed themselves in their correspondence on the subject of homosexuality was through references to ancient Greek culture, such as the intimate friendship between Callicrates, "the most beautiful man among the Spartans", and the soldier Aristodemus. Symonds was influenced by Karl Otfried Müller's work on the Dorians, which included an "unembarrassed" examination of the place of pederasty in Spartan pedagogy, military life, and society. Symonds distinguished between "heroic love", for which the ideal friendship of Achilles and Patroclus served as a model, and "Greek love", which combined social ideals with "vulgar" reality. Symonds envisioned a "nationalist homosexuality" based on the model of Greek love, distanced from effeminacy and "debasing" behaviors and viewed as "in its origin and essence, military". He tried to reconcile his presentation of Greek love with Christian and chivalrous values. His strategy for influencing social acceptance of homosexuality and legal reform in England included evoking an idealized Greek model that reflected Victorian moral values such as honor, devotion, and self-sacrifice.

The trial of Oscar Wilde

During his relationship with Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, Wilde frequently invoked the historical precedent of Greek models of love and masculinity, calling Douglas the contemporary "Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly," in a letter to him in July 1893. The trial of Oscar Wilde marked the end of the period when proponents of "Greek love" could hope to legitimate homosexuality by appeals to a classical model. During the cross examination, Wilde defended his statement that "pleasure is the only thing one should live for," by acknowledging: "I am, on that point, entirely on the side of the ancients—the Greeks. It is a pagan idea." With the rise of sexology, however, that kind of defense failed to hold.

20th and 21st centuries

The legacy of Greece in homosexual aesthetics became problematic, and the meaning of a "costume" derived from classical antiquity was questioned. The French theorist Michel Foucault (1926–1984), perhaps best known for his work The History of Sexuality, rejected essentialist conceptions of gay history, and fostered a now "widely accepted" view that "Greek love is not a prefiguration of modern homosexuality."