A black body or blackbody is an idealized physical body that absorbs all incident electromagnetic radiation, regardless of frequency or angle of incidence. The radiation emitted by a black body in thermal equilibrium with its environment is called black-body radiation. The name "black body" is given because it absorbs all colors of light. In contrast, a white body is one with a "rough surface that reflects all incident rays completely and uniformly in all directions."

A black body in thermal equilibrium (that is, at a constant temperature) emits electromagnetic black-body radiation. The radiation is emitted according to Planck's law, meaning that it has a spectrum that is determined by the temperature alone (see figure at right), not by the body's shape or composition.

An ideal black body in thermal equilibrium has two main properties:

- It is an ideal emitter: at every frequency, it emits as much or more thermal radiative energy as any other body at the same temperature.

- It is a diffuse emitter: measured per unit area perpendicular to the direction, the energy is radiated isotropically, independent of direction.

Real materials emit energy at a fraction—called the emissivity—of black-body energy levels. By definition, a black body in thermal equilibrium has an emissivity ε = 1. A source with a lower emissivity, independent of frequency, is often referred to as a gray body. Constructing black bodies with an emissivity as close to 1 as possible remains a topic of current interest.

In astronomy, the radiation from stars and planets is sometimes characterized in terms of an effective temperature, the temperature of a black body that would emit the same total flux of electromagnetic energy.

Definition

The idea of a black body originally was introduced by Gustav Kirchhoff in 1860 as follows:

...the supposition that bodies can be imagined which, for infinitely small thicknesses, completely absorb all incident rays, and neither reflect nor transmit any. I shall call such bodies perfectly black, or, more briefly, black bodies.

A more modern definition drops the reference to "infinitely small thicknesses":

An ideal body is now defined, called a blackbody. A blackbody allows all incident radiation to pass into it (no reflected energy) and internally absorbs all the incident radiation (no energy transmitted through the body). This is true for radiation of all wavelengths and for all angles of incidence. Hence the blackbody is a perfect absorber for all incident radiation.

Idealizations

This section describes some concepts developed in connection with black bodies.

Cavity with a hole

A widely used model of a black surface is a small hole in a cavity with walls that are opaque to radiation. Radiation incident on the hole will pass into the cavity, and is very unlikely to be re-emitted if the cavity is large. The hole is not quite a perfect black surface—in particular, if the wavelength of the incident radiation is greater than the diameter of the hole, part will be reflected. Similarly, even in perfect thermal equilibrium, the radiation inside a finite-sized cavity will not have an ideal Planck spectrum for wavelengths comparable to or larger than the size of the cavity.

Suppose the cavity is held at a fixed temperature T and the radiation trapped inside the enclosure is at thermal equilibrium with the enclosure. The hole in the enclosure will allow some radiation to escape. If the hole is small, radiation passing in and out of the hole has negligible effect upon the equilibrium of the radiation inside the cavity. This escaping radiation will approximate black-body radiation that exhibits a distribution in energy characteristic of the temperature T and does not depend upon the properties of the cavity or the hole, at least for wavelengths smaller than the size of the hole. See the figure in the Introduction for the spectrum as a function of the frequency of the radiation, which is related to the energy of the radiation by the equation E = hf, with E = energy, h = Planck's constant, f = frequency.

At any given time the radiation in the cavity may not be in thermal equilibrium, but the second law of thermodynamics states that if left undisturbed it will eventually reach equilibrium, although the time it takes to do so may be very long. Typically, equilibrium is reached by continual absorption and emission of radiation by material in the cavity or its walls. Radiation entering the cavity will be "thermalized" by this mechanism: the energy will be redistributed until the ensemble of photons achieves a Planck distribution. The time taken for thermalization is much faster with condensed matter present than with rarefied matter such as a dilute gas. At temperatures below billions of Kelvin, direct photon–photon interactions are usually negligible compared to interactions with matter. Photons are an example of an interacting boson gas, and as described by the H-theorem, under very general conditions any interacting boson gas will approach thermal equilibrium.

Transmission, absorption, and reflection

A body's behavior with regard to thermal radiation is characterized by its transmission τ, absorption α, and reflection ρ.

The boundary of a body forms an interface with its surroundings, and this interface may be rough or smooth. A nonreflecting interface separating regions with different refractive indices must be rough, because the laws of reflection and refraction governed by the Fresnel equations for a smooth interface require a reflected ray when the refractive indices of the material and its surroundings differ. A few idealized types of behavior are given particular names:

An opaque body is one that transmits none of the radiation that reaches it, although some may be reflected. That is, τ = 0 and α + ρ = 1.

A transparent body is one that transmits all the radiation that reaches it. That is, τ = 1 and α = ρ = 0.

A grey body is one where α, ρ and τ are constant for all wavelengths; this term also is used to mean a body for which α is temperature- and wavelength-independent.

A white body is one for which all incident radiation is reflected uniformly in all directions: τ = 0, α = 0, and ρ = 1.

For a black body, τ = 0, α = 1, and ρ = 0. Planck offers a theoretical model for perfectly black bodies, which he noted do not exist in nature: besides their opaque interior, they have interfaces that are perfectly transmitting and non-reflective.

Kirchhoff's perfect black bodies

Kirchhoff in 1860 introduced the theoretical concept of a perfect black body with a completely absorbing surface layer of infinitely small thickness, but Planck noted some severe restrictions upon this idea. Planck noted three requirements upon a black body: the body must (i) allow radiation to enter but not reflect; (ii) possess a minimum thickness adequate to absorb the incident radiation and prevent its re-emission; (iii) satisfy severe limitations upon scattering to prevent radiation from entering and bouncing back out. As a consequence, Kirchhoff's perfect black bodies that absorb all the radiation that falls on them cannot be realized in an infinitely thin surface layer, and impose conditions upon scattering of the light within the black body that are difficult to satisfy.

Realizations

A realization of a black body refers to a real world, physical embodiment. Here are a few.

Cavity with a hole

In 1898, Otto Lummer and Ferdinand Kurlbaum published an account of their cavity radiation source. Their design has been used largely unchanged for radiation measurements to the present day. It was a hole in the wall of a platinum box, divided by diaphragms, with its interior blackened with iron oxide. It was an important ingredient for the progressively improved measurements that led to the discovery of Planck's law. A version described in 1901 had its interior blackened with a mixture of chromium, nickel, and cobalt oxides. See also Hohlraum.

Near-black materials

There is interest in blackbody-like materials for camouflage and radar-absorbent materials for radar invisibility. They also have application as solar energy collectors, and infrared thermal detectors. As a perfect emitter of radiation, a hot material with black body behavior would create an efficient infrared heater, particularly in space or in a vacuum where convective heating is unavailable. They are also useful in telescopes and cameras as anti-reflection surfaces to reduce stray light, and to gather information about objects in high-contrast areas (for example, observation of planets in orbit around their stars), where blackbody-like materials absorb light that comes from the wrong sources.

It has long been known that a lamp-black coating will make a body nearly black. An improvement on lamp-black is found in manufactured carbon nanotubes. Nano-porous materials can achieve refractive indices nearly that of vacuum, in one case obtaining average reflectance of 0.045%. In 2009, a team of Japanese scientists created a material called nanoblack which is close to an ideal black body, based on vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes. This absorbs between 98% and 99% of the incoming light in the spectral range from the ultra-violet to the far-infrared regions.

Other examples of nearly perfect black materials are super black, prepared by chemically etching a nickel–phosphorus alloy, vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays (like VantaBlack) and flower carbon nanostructures; all absorb 99.9% of light or more.

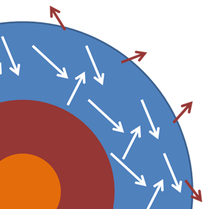

Stars and planets

A star or planet often is modeled as a black body, and electromagnetic radiation emitted from these bodies as black-body radiation. The figure shows a highly schematic cross-section to illustrate the idea. The photosphere of the star, where the emitted light is generated, is idealized as a layer within which the photons of light interact with the material in the photosphere and achieve a common temperature T that is maintained over a long period of time. Some photons escape and are emitted into space, but the energy they carry away is replaced by energy from within the star, so that the temperature of the photosphere is nearly steady. Changes in the core lead to changes in the supply of energy to the photosphere, but such changes are slow on the time scale of interest here. Assuming these circumstances can be realized, the outer layer of the star is somewhat analogous to the example of an enclosure with a small hole in it, with the hole replaced by the limited transmission into space at the outside of the photosphere. With all these assumptions in place, the star emits black-body radiation at the temperature of the photosphere.

Using this model the effective temperature of stars is estimated, defined as the temperature of a black body that yields the same surface flux of energy as the star. If a star were a black body, the same effective temperature would result from any region of the spectrum. For example, comparisons in the B (blue) or V (visible) range lead to the so-called B-V color index, which increases the redder the star, with the Sun having an index of +0.648 ± 0.006. Combining the U (ultraviolet) and the B indices leads to the U-B index, which becomes more negative the hotter the star and the more the UV radiation. Assuming the Sun is a type G2 V star, its U-B index is +0.12. The two indices for two types of most common star sequences are compared in the figure (diagram) with the effective surface temperature of the stars if they were perfect black bodies. There is a rough correlation. For example, for a given B-V index measurement, the curves of both most common sequences of star (the main sequence and the supergiants) lie below the corresponding black-body U-B index that includes the ultraviolet spectrum, showing that both groupings of star emit less ultraviolet light than a black body with the same B-V index. It is perhaps surprising that they fit a black body curve as well as they do, considering that stars have greatly different temperatures at different depths. For example, the Sun has an effective temperature of 5780 K, which can be compared to the temperature of its photosphere (the region generating the light), which ranges from about 5000 K at its outer boundary with the chromosphere to about 9500 K at its inner boundary with the convection zone approximately 500 km (310 mi) deep.

Black holes

A black hole is a region of spacetime from which nothing escapes. Around a black hole there is a mathematically defined surface called an event horizon that marks the point of no return. It is called "black" because it absorbs all the light that hits the horizon, reflecting nothing, making it almost an ideal black body (radiation with a wavelength equal to or larger than the diameter of the hole may not be absorbed, so black holes are not perfect black bodies). Physicists believe that to an outside observer, black holes have a non-zero temperature and emit black-body radiation, radiation with a nearly perfect black-body spectrum, ultimately evaporating. The mechanism for this emission is related to vacuum fluctuations in which a virtual pair of particles is separated by the gravity of the hole, one member being sucked into the hole, and the other being emitted. The energy distribution of emission is described by Planck's law with a temperature T:

where c is the speed of light, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, kB is the Boltzmann constant, G is the gravitational constant and M is the mass of the black hole. These predictions have not yet been tested either observationally or experimentally.

Cosmic microwave background radiation

The Big Bang theory is based upon the cosmological principle, which states that on large scales the Universe is homogeneous and isotropic. According to theory, the Universe approximately a second after its formation was a near-ideal black body in thermal equilibrium at a temperature above 1010 K. The temperature decreased as the Universe expanded and the matter and radiation in it cooled. The cosmic microwave background radiation observed today is "the most perfect black body ever measured in nature". It has a nearly ideal Planck spectrum at a temperature of about 2.7 K. It departs from the perfect isotropy of true black-body radiation by an observed anisotropy that varies with angle on the sky only to about one part in 100,000.

Radiative cooling

The integration of Planck's law over all frequencies provides the total energy per unit of time per unit of surface area radiated by a black body maintained at a temperature T, and is known as the Stefan–Boltzmann law:

where σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, σ ≈ 5.67×10−8 W⋅m−2⋅K−4 To remain in thermal equilibrium at constant temperature T, the black body must absorb or internally generate this amount of power P over the given area A.

The cooling of a body due to thermal radiation is often approximated using the Stefan–Boltzmann law supplemented with a "gray body" emissivity ε ≤ 1 (P/A = εσT4). The rate of decrease of the temperature of the emitting body can be estimated from the power radiated and the body's heat capacity. This approach is a simplification that ignores details of the mechanisms behind heat redistribution (which may include changing composition, phase transitions or restructuring of the body) that occur within the body while it cools, and assumes that at each moment in time the body is characterized by a single temperature. It also ignores other possible complications, such as changes in the emissivity with temperature, and the role of other accompanying forms of energy emission, for example, emission of particles like neutrinos.

If a hot emitting body is assumed to follow the Stefan–Boltzmann law and its power emission P and temperature T are known, this law can be used to estimate the dimensions of the emitting object, because the total emitted power is proportional to the area of the emitting surface. In this way it was found that X-ray bursts observed by astronomers originated in neutron stars with a radius of about 10 km, rather than black holes as originally conjectured. An accurate estimate of size requires some knowledge of the emissivity, particularly its spectral and angular dependence.