Constitutional monarchies range from countries such as Liechtenstein, Monaco, Morocco, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain and Bhutan, where the constitution grants substantial discretionary powers to the sovereign, to countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, and Japan, where the monarch retains significantly less, if any, personal discretion in the exercise of their authority.

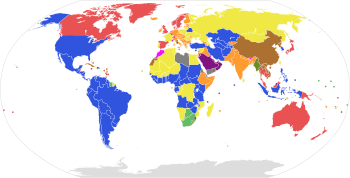

- Map legend

1 This map was compiled according to the Wikipedia list of countries by system of government. See there for sources.Full presidential republics2 Semi-presidential republics2 Republics with an executive president elected by or nominated by the legislature that may or may not be subject to parliamentary confidence Parliamentary republics2 Parliamentary constitutional monarchies where royalty does not hold significant power Parliamentary constitutional monarchies which have a separate head of government but where royalty holds significant executive and/or legislative power Absolute monarchies One-party states Countries where constitutional provisions for government have been suspended (e.g. military juntas) Countries that do not fit any of the above systems (e.g. provisional governments/unclear political situations) Overseas possessions, colonies, and places without governments Directorial system

2 This map presents only the de jure form of government, and not the de facto degree of democracy. Some countries which are de jure republics are de facto authoritarian regimes. For a measure of the degree of democracy in countries around the world, see the Democracy Index or V-Dem Democracy indices.

Constitutional monarchy may refer to a system in which the monarch acts as a non-party political head of state under the constitution, whether codified or uncodified. While most monarchs may hold formal authority and the government may legally operate in the monarch's name, in the form typical in Europe the monarch no longer personally sets public policy or chooses political leaders. Political scientist Vernon Bogdanor, paraphrasing Thomas Macaulay, has defined a constitutional monarch as "A sovereign who reigns but does not rule".

In addition to acting as a visible symbol of national unity, a constitutional monarch may hold formal powers such as dissolving parliament or giving royal assent to legislation. However, such powers generally may only be exercised strictly in accordance with either written constitutional principles or unwritten constitutional conventions, rather than any personal political preferences of the sovereign. In The English Constitution, British political theorist Walter Bagehot identified three main political rights which a constitutional monarch may freely exercise: the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn. Many constitutional monarchies still retain significant authorities or political influence, however, such as through certain reserve powers, and may also play an important political role.

The United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms are all constitutional monarchies in the Westminster system of constitutional governance. Two constitutional monarchies – Malaysia and Cambodia – are elective monarchies, in which the ruler is periodically selected by a small electoral college.

Strongly limited constitutional monarchies, such as the United Kingdom and Australia, have been referred to as crowned republics by writers H. G. Wells and Glenn Patmore.

The concept of semi-constitutional monarch identifies constitutional monarchies where the monarch retains substantial powers, on a par with a president in a presidential or semi-presidential system. As a result, constitutional monarchies where the monarch has a largely ceremonial role may also be referred to as 'parliamentary monarchies' to differentiate them from semi-constitutional monarchies.

History

The oldest constitutional monarchy dating back to ancient times was that of the Hittites. They were an ancient Anatolian people that lived during the Bronze Age whose king had to share his authority with an assembly, called the Panku, which was the equivalent to a modern-day deliberative assembly or a legislature. Members of the Panku came from scattered noble families who worked as representatives of their subjects in an adjutant or subaltern federal-type landscape.

Constitutional and absolute monarchy

England, Scotland and the United Kingdom

In the Kingdom of England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 furthered the constitutional monarchy, restricted by laws such as the Bill of Rights 1689 and the Act of Settlement 1701, although the first form of constitution was enacted with the Magna Carta of 1215. At the same time, in Scotland, the Convention of Estates enacted the Claim of Right Act 1689, which placed similar limits on the Scottish monarchy.

Queen Anne was the last monarch to veto an Act of Parliament when, on 11 March 1708, she blocked the Scottish Militia Bill. However Hanoverian monarchs continued to selectively dictate government policies. For instance King George III constantly blocked Catholic Emancipation, eventually precipitating the resignation of William Pitt the Younger as prime minister in 1801. The sovereign's influence on the choice of prime minister gradually declined over this period. King William IV was the last monarch to dismiss a prime minister, when in 1834 he removed Lord Melbourne as a result of Melbourne's choice of Lord John Russell as Leader of the House of Commons. Queen Victoria was the last monarch to exercise real personal power, but this diminished over the course of her reign. In 1839, she became the last sovereign to keep a prime minister in power against the will of Parliament when the Bedchamber crisis resulted in the retention of Lord Melbourne's administration. By the end of her reign, however, she could do nothing to block the unacceptable (to her) premierships of William Gladstone, although she still exercised power in appointments to the Cabinet. For example in 1886 she vetoed Gladstone's choice of Hugh Childers as War Secretary in favour of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman.

Today, the role of the British monarch is by convention effectively ceremonial. The British Parliament and the Government – chiefly in the office of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom – exercise their powers under "Royal (or Crown) Prerogative": on behalf of the monarch and through powers still formally possessed by the monarch.

No person may accept significant public office without swearing an oath of allegiance to the King. With few exceptions, the monarch is bound by constitutional convention to act on the advice of the Government.

Continental Europe

Poland developed the first constitution for a monarchy in continental Europe, with the Constitution of 3 May 1791; it was the second single-document constitution in the world just after the first republican Constitution of the United States. Constitutional monarchy also occurred briefly in the early years of the French Revolution, but much more widely afterwards. Napoleon Bonaparte is considered the first monarch proclaiming himself as an embodiment of the nation, rather than as a divinely appointed ruler; this interpretation of monarchy is germane to continental constitutional monarchies. German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in his work Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820), gave the concept a philosophical justification that concurred with evolving contemporary political theory and the Protestant Christian view of natural law. Hegel's forecast of a constitutional monarch with very limited powers whose function is to embody the national character and provide constitutional continuity in times of emergency was reflected in the development of constitutional monarchies in Europe and Japan.

Executive monarchy versus ceremonial monarchy

There exist at least two different types of constitutional monarchies in the modern world — executive and ceremonial. In executive monarchies, the monarch wields significant (though not absolute) power. The monarchy under this system of government is a powerful political (and social) institution. By contrast, in ceremonial monarchies, the monarch holds little or no actual power or direct political influence, though they frequently have a great deal of social and cultural influence.

Ceremonial and executive monarchy should not be confused with democratic and non-democratic monarchical systems. For example, in Liechtenstein and Monaco, the ruling monarchs wield significant executive power. However, while they are theoretically very powerful within their small states, they are not absolute monarchs and have very limited de facto power compared to the Islamic monarchs, which is why their countries are generally considered to be liberal democracies. For instance, when Hereditary Prince Alois of Liechtenstein threatened to veto a referendum to legalize abortion in 2011, it came as a surprise because the prince had not vetoed any law for over 30 years (in the end, this referendum failed to make it to a vote).

Modern constitutional monarchy

As originally conceived, a constitutional monarch was head of the executive branch and quite a powerful figure even though their power was limited by the constitution and the elected parliament. Some of the framers of the U.S. Constitution may have envisioned the president as an elected constitutional monarch, as the term was then understood, following Montesquieu's account of the separation of powers.

The present-day concept of a constitutional monarchy developed in the United Kingdom, where the democratically elected parliaments, and their leader, the prime minister, exercise power, with the monarchs having ceded power and remaining as a titular position. In many cases the monarchs, while still at the very top of the political and social hierarchy, were given the status of "servants of the people" to reflect the new, egalitarian position. In the course of France's July Monarchy, Louis-Philippe I was styled "King of the French" rather than "King of France".

Following the unification of Germany, Otto von Bismarck rejected the British model. In the constitutional monarchy established under the Constitution of the German Empire which Bismarck inspired, the Kaiser retained considerable actual executive power, while the Imperial Chancellor needed no parliamentary vote of confidence and ruled solely by the imperial mandate. However, this model of constitutional monarchy was discredited and abolished following Germany's defeat in the First World War. Later, Fascist Italy could also be considered a constitutional monarchy, in that there was a king as the titular head of state while actual power was held by Benito Mussolini under a constitution. This eventually discredited the Italian monarchy and led to its abolition in 1946. After the Second World War, surviving European monarchies almost invariably adopted some variant of the constitutional monarchy model originally developed in Britain.

Nowadays a parliamentary democracy that is a constitutional monarchy is considered to differ from one that is a republic only in detail rather than in substance. In both cases, the titular head of state—monarch or president—serves the traditional role of embodying and representing the nation, while the government is carried on by a cabinet composed predominantly of elected Members of Parliament.

However, three important factors distinguish monarchies such as the United Kingdom from systems where greater power might otherwise rest with Parliament. These are:

- the Royal Prerogative, under which the monarch may exercise power under certain very limited circumstances;

- Sovereign Immunity, under which the monarch may do no wrong under the law because the responsible government is instead deemed accountable; and

- the immunity of the monarch from some taxation or restrictions on property use.

Other privileges may be nominal or ceremonial (e.g. where the executive, judiciary, police or armed forces act on the authority of or owe allegiance to the Crown).

Today slightly more than a quarter of constitutional monarchies are Western European countries, including the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Luxembourg, Monaco, Liechtenstein and Sweden. However, the two most populous constitutional monarchies in the world are in Asia: Japan and Thailand. In these countries, the prime minister holds the day-to-day powers of governance, while the monarch retains residual (but not always insignificant) powers. The powers of the monarch differ between countries. In Denmark and in Belgium, for example, the monarch formally appoints a representative to preside over the creation of a coalition government following a parliamentary election, while in Norway the King chairs special meetings of the cabinet.

In nearly all cases, the monarch is still the nominal chief executive, but is bound by convention to act on the advice of the Cabinet. Only a few monarchies (most notably Japan and Sweden) have amended their constitutions so that the monarch is no longer even the nominal chief executive.

There are fifteen constitutional monarchies under King Charles III, which are known as Commonwealth realms. Unlike some of their continental European counterparts, the Monarch and his Governors-General in the Commonwealth realms hold significant "reserve" or "prerogative" powers, to be wielded in times of extreme emergency or constitutional crises, usually to uphold parliamentary government. For example, during the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, the Governor-General dismissed the Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. The Australian Senate had threatened to block the Government's budget by refusing to pass the necessary appropriation bills. On 11 November 1975, Whitlam intended to call a half-Senate election to try to break the deadlock. When he sought the Governor-General's approval of the election, the Governor-General instead dismissed him as Prime Minister. Shortly after that, he installed leader of the opposition Malcolm Fraser in his place. Acting quickly before all parliamentarians became aware of the government change, Fraser and his allies secured passage of the appropriation bills, and the Governor-General dissolved Parliament for a double dissolution election. Fraser and his government were returned with a massive majority. This led to much speculation among Whitlam's supporters as to whether this use of the Governor-General's reserve powers was appropriate, and whether Australia should become a republic. Among supporters of constitutional monarchy, however, the event confirmed the monarchy's value as a source of checks and balances against elected politicians who might seek powers in excess of those conferred by the constitution, and ultimately as a safeguard against dictatorship.

In Thailand's constitutional monarchy, the monarch is recognized as the Head of State, Head of the Armed Forces, Upholder of the Buddhist Religion, and Defender of the Faith. The immediate former King, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was the longest-reigning monarch in the world and in all of Thailand's history, before passing away on 13 October 2016. Bhumibol reigned through several political changes in the Thai government. He played an influential role in each incident, often acting as mediator between disputing political opponents. (See Bhumibol's role in Thai Politics.) Among the powers retained by the Thai monarch under the constitution, lèse majesté protects the image of the monarch and enables him to play a role in politics. It carries strict criminal penalties for violators. Generally, the Thai people were reverent of Bhumibol. Much of his social influence arose from this reverence and from the socioeconomic improvement efforts undertaken by the royal family.

In the United Kingdom, a frequent debate centres on when it is appropriate for a British monarch to act. When a monarch does act, political controversy can often ensue, partially because the neutrality of the crown is seen to be compromised in favour of a partisan goal, while some political scientists champion the idea of an "interventionist monarch" as a check against possible illegal action by politicians. For instance, the monarch of the United Kingdom can theoretically exercise an absolute veto over legislation by withholding royal assent. However, no monarch has done so since 1708, and it is widely believed that this and many of the monarch's other political powers are lapsed powers.

List of current constitutional monarchies

There are currently 43 monarchies worldwide.

Ceremonial constitutional monarchies

Executive constitutional monarchies

Former constitutional monarchies

- The Kingdom of Afghanistan was a constitutional monarchy under Mohammad Zahir Shah from 1964 to 1973.

- Kingdom of Albania from 1928 until 1939, Albania was a Constitutional Monarchy ruled by the House of Zogu, King Zog I.

- The Anglo-Corsican Kingdom was a brief period in the history of Corsica (1794–1796) when the island broke with Revolutionary France and sought military protection from Great Britain. Corsica became an independent kingdom under George III of the United Kingdom, but with its own elected parliament and a written constitution guaranteeing local autonomy and democratic rights.

- Barbados from gaining its independence in 1966 until 2021, was a constitutional monarchy in the Commonwealth of Nations with a Governor-General representing the Monarchy of Barbados. After an extensive history of republican movements, a republic was declared on 30 November 2021.

- Brazil from 1822, with the proclamation of independence and rise of the Empire of Brazil by Pedro I of Brazil to 1889, when Pedro II was deposed by a military coup.

- Kingdom of Bulgaria until 1946 when Tsar Simeon was deposed by the communist assembly.

- Many republics in the Commonwealth of Nations were constitutional monarchies for some period after their independence, including South Africa (1910–1961), Ceylon from 1948 to 1972 (now Sri Lanka), Fiji (1970–1987), Gambia (1965–1970), Ghana (1957–1960), Guyana (1966–1970), Trinidad and Tobago (1962–1976), and Barbados (1966–2021).

- Egypt was a constitutional monarchy starting from the later part of the Khedivate, with parliamentary structures and a responsible khedival ministry developing in the 1860s and 1870s. The constitutional system continued through the Khedivate period and developed during the Sultanate and then Kingdom of Egypt, which established an essentially democratic liberal constitutional regime under the Egyptian Constitution of 1923. This system persisted until the declaration of a republic after the Free Officers Movement coup in 1952. For most of this period, however, Egypt was occupied by the United Kingdom, and overall political control was in the hands of British colonial officials nominally accredited as diplomats to the Egyptian royal court but actually able to overrule any decision of the monarch or elected government.

- The Grand Principality of Finland was a constitutional monarchy though its ruler, Alexander I, was simultaneously an autocrat and absolute ruler in Russia.

- France, several times from 1789 through the 19th century. The transformation of the Estates General of 1789 into the National Assembly initiated an ad-hoc transition from the absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime to a new constitutional system. France formally became an executive constitutional monarchy with the promulgation of the French Constitution of 1791, which took effect on 1 October of that year. This first French constitutional monarchy was short-lived, ending with the overthrow of the monarchy and establishment of the French First Republic after the Insurrection of 10 August 1792. Several years later, in 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte proclaimed himself Emperor of the French in what was ostensibly a constitutional monarchy, though modern historians often call his reign as an absolute monarchy. The Bourbon Restoration (under Louis XVIII and Charles X), the July Monarchy (under Louis-Philippe), and the Second Empire (under Napoleon III) were also constitutional monarchies, although the power of the monarch varied considerably between them and sometimes within them.

- The German Empire from 1871 to 1918, (as well as earlier confederations, and the monarchies it consisted of) was also a constitutional monarchy—see Constitution of the German Empire.

- Greece until 1973 when Constantine II was deposed by the military government. The decision was formalized by a plebiscite 8 December 1974.

- Hawaii, which was an absolute monarchy from its founding in 1810, transitioned to a constitutional monarchy in 1840 when King Kamehameha III promulgated the kingdom's first constitution. This constitutional form of government continued until the monarchy was overthrown in an 1893 coup.

- The Kingdom of Hungary. In 1848–1849 and 1867–1918 as part of Austria-Hungary. In the interwar period (1920–1944) Hungary remained a constitutional monarchy without a reigning monarch.

- Iceland. The Act of Union, a 1 December 1918 agreement with Denmark, established Iceland as a sovereign kingdom united with Denmark under a common king. Iceland abolished the monarchy and became a republic on 17 June 1944 after the Icelandic constitutional referendum, 24 May 1944.

- India was a constitutional monarchy, with George VI as head of state and the Earl Mountbatten as governor-general, for a brief period between gaining its independence from the British on 15 August 1947 and becoming a republic when it adopted its constitution on 26 January 1950, henceforth celebrated as Republic Day.

- Pahlavi Iran under Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was a constitutional monarchy, which had been originally established during the Persian Constitutional Revolution in 1906.

- Italy until 2 June 1946, when a referendum proclaimed the end of the Kingdom and the beginning of the Republic.

- The Kingdom of Laos was a constitutional monarchy until 1975, when Sisavang Vatthana was forced to abdicate by the communist Pathet Lao.

- Malta was a constitutional monarchy with Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta, represented by a Governor-General appointed by her, for the first ten years of independence from 21 September 1964 to the declaration of the Republic of Malta on 13 December 1974.

- Mexico was twice an Empire. The First Mexican Empire lasted from 19 May 1822, to 19 March 1823, with Agustin I elected as emperor. Then, the Mexican monarchists and conservatives, with the help of the Austrian and Spanish crowns and Napoleon III of France, elected Maximilian of Austria as Emperor of Mexico. This constitutional monarchy lasted three years, from 1864 to 1867.

- Montenegro until 1918 when it merged with Serbia and other areas to form Yugoslavia.

- Nepal until 28 May 2008, when King Gyanendra was deposed, and the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal was declared.

- Ottoman Empire from 1876 until 1878 and again from 1908 until the dissolution of the empire in 1922.

- Pakistan was a constitutional monarchy for a brief period between gaining its independence from the British on 14 August 1947 and becoming a republic when it adopted the first Constitution of Pakistan on 23 March 1956. The Dominion of Pakistan had a total of two monarchs (George VI and Elizabeth II) and four Governor-Generals (Muhammad Ali Jinnah being the first). Republic Day (or Pakistan Day) is celebrated every year on 23 March to commemorate the adoption of its Constitution and the transition of the Dominion of Pakistan to the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

- The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formed after the Union of Lublin in 1569 and lasting until the final partition of the state in 1795, operated much like many modern European constitutional monarchies (into which it was officially changed by the establishment of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, which historian Norman Davies calls "the first constitution of its kind in Europe"). The legislators of the unified state truly did not see it as a monarchy at all, but as a republic under the presidency of the King . Poland–Lithuania also followed the principle of Rex regnat et non gubernat, had a bicameral parliament, and a collection of entrenched legal documents amounting to a constitution along the lines of the modern United Kingdom. The King was elected, and had the duty of maintaining the people's rights.

- Portugal was a monarchy since 1139 and a constitutional monarchy from 1822 to 1828, and again from 1834 until 1910, when Manuel II was overthrown by a military coup. From 1815 to 1825 it was part of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves which was a constitutional monarchy for the years 1820–23.

- Kingdom of Romania from its establishment in 1881 until 1947 when Michael I was forced to abdicate by the communists.

- Kingdom of Serbia from 1882 until 1918, when it merged with the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs into the unitary Yugoslav Kingdom, that was led by the Serbian Karadjordjevic dynasty.

- Trinidad and Tobago was a constitutional monarchy with Elizabeth II as Queen of Trinidad and Tobago, represented by a Governor-General appointed by her, for the first fourteen years of independence from 31 August 1962 to the declaration of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago on 1 August 1976. Republic Day is celebrated every year on 24 September.

- Yugoslavia from 1918 (as Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) until 1929 and from 1931 (as Kingdom of Yugoslavia) until 1944 when under pressure from the Allies Peter II recognized the communist government.

Unusual constitutional monarchies

- Andorra is a diarchy, being headed by two co-princes: the bishop of Urgell and the president of France.

- Andorra, Monaco and Liechtenstein are the only countries with reigning princes.

- Belgium is the only remaining explicit popular monarchy: the formal title of its king is King of the Belgians rather than King of Belgium. Historically, several defunct constitutional monarchies followed this model; the Belgian formulation is recognized to have been modelled on the title "King of the French" granted by the Charter of 1830 to monarch of the July Monarchy.

- Japan is the only country remaining with an emperor.

- Luxembourg is the only country remaining with a grand duke.

- Malaysia is a federal country with an elective monarchy: the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is selected from among nine state rulers who are also constitutional monarchs themselves.

- Papua New Guinea. Unlike in most other Commonwealth realms, sovereignty is constitutionally vested in the citizenry of Papua New Guinea and the preamble to the constitution states "that all power belongs to the people—acting through their duly elected representatives". The monarch has been, according to section 82 of the constitution, "requested by the people of Papua New Guinea, through their Constituent Assembly, to become [monarch] and Head of State of Papua New Guinea" and thus acts in that capacity.

- Spain. The Constitution of Spain does not even recognize the monarch as sovereign, but just as the head of state (Article 56). Article 1, Section 2, states that "the national sovereignty is vested in the Spanish people".

- United Arab Emirates is a federal country with an elective monarchy, the President or Ra'is, being selected from among the rulers of the seven emirates, each of whom is a hereditary absolute monarch in their own emirate.