| United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Multilateral environmental agreement |

| Context | Environmentalism |

| Drafted | 9 May 1992 |

| Signed | 4–14 June 1992 20 June 1992 – 19 June 1993 |

| Location | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil New York, United States |

| Effective | 21 March 1994 |

| Condition | Ratification by 50 states |

| Signatories | 165 |

| Parties | 198 |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Languages | |

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established an international environmental treaty to combat "dangerous human interference with the climate system", in part by stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. It was signed by 154 states at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), informally known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992. Its original secretariat was in Geneva but relocated to Bonn in 1996. It entered into force on 21 March 1994.

The treaty called for ongoing scientific research and regular meetings, negotiations, and future policy agreements designed to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

The Kyoto Protocol, which was signed in 1997 and ran from 2005 to 2020, was the first implementation of measures under the UNFCCC. The Kyoto Protocol was superseded by the Paris Agreement, which entered into force in 2016. By 2022, the UNFCCC had 198 parties. Its supreme decision-making body, the Conference of the Parties (COP), meets annually to assess progress in dealing with climate change. Because key signatory states are not adhering to their individual commitments, the UNFCCC has been criticized as being unsuccessful in reducing the emission of carbon dioxide since its adoption.

The treaty established different responsibilities for three categories of signatory states. These categories are developed countries, developed countries with special financial responsibilities, and developing countries. The developed countries, also called Annex 1 countries, originally consisted of 38 states, 13 of which were Eastern European states in transition to democracy and market economies, and the European Union. All belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Annex 1 countries are called upon to adopt national policies and take corresponding measures on the mitigation of climate change by limiting their anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases as well as to report on steps adopted with the aim of returning individually or jointly to their 1990 emissions levels. The developed countries with special financial responsibilities are also called Annex II countries. They include all of the Annex I countries with the exception of those in transition to democracy and market economies. Annex II countries are called upon to provide new and additional financial resources to meet the costs incurred by developing countries in complying with their obligation to produce national inventories of their emissions by sources and their removals by sinks for all greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol. The developing countries are then required to submit their inventories to the UNFCCC Secretariat.

Treaties

Convention Agreement in 1992

The text of the Framework Convention was produced during the meeting of an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee in New York from 30 April to 9 May 1992. The Convention was adopted on 9 May 1992 and opened for signature on 4 June 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro (known by its popular title, the Earth Summit). On 12 June 1992, 154 nations signed the UNFCCC, which upon ratification committed signatories' governments to reduce atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases with the goal of "preventing dangerous anthropogenic interference with Earth's climate system". This commitment would require substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (see the later section, "Stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations"). The parties to the convention have met annually from 1995 in Conferences of the Parties (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change.

Article 3(1) of the Convention states that Parties should act to protect the climate system on the basis of "common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities", and that developed country Parties should "take the lead" in addressing climate change. Under Article 4, all Parties make general commitments to address climate change through, for example, climate change mitigation and adapting to the eventual impacts of climate change. Article 4(7) states:

The extent to which developing country Parties will effectively implement their commitments under the Convention will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments under the Convention related to financial resources and transfer of technology and will take fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties.

The Framework Convention specifies the aim of Annex I Parties was stabilizing their greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide and other anthropogenic greenhouse gases not regulated under the Montreal Protocol) at 1990 levels, by 2000.

"UNFCCC" is also the name of the United Nations Secretariat charged with supporting the operation of the convention, with offices in Haus Carstanjen, and the UN Campus (known as Langer Eugen) in Bonn, Germany. From 2010 to 2016 the head of the secretariat was Christiana Figueres. In July 2016, Patricia Espinosa succeeded Figueres. The Secretariat, augmented through the parallel efforts of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), aims to gain consensus through meetings and the discussion of various strategies. Since the signing of the UNFCCC treaty, Conferences of the Parties (COPs) have discussed how to achieve the treaty's aims.

Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE)

Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE) is a term adopted by the UNFCCC in 2015 to have a better name for this topic than "Article 6". It refers to Article 6 of the convention's original text (1992), focusing on six priority areas: education, training, public awareness, public participation, public access to information, and international cooperation on these issues. The implementation of all six areas has been identified as the pivotal factor for everyone to understand and participate in solving the challenges presented by climate change. ACE calls on governments to develop and implement educational and public awareness programmes, train scientific, technical and managerial personnel, foster access to information, and promote public participation in addressing climate change and its effects. It also urges countries to cooperate in this process, by exchanging good practices and lessons learned, and strengthening national institutions. This wide scope of activities is guided by specific objectives that, together, are seen as crucial for effectively implementing climate adaptation and mitigation actions, and for achieving the ultimate objective of the UNFCCC.

Kyoto Protocol

The 1st Conference of the Parties (COP1) decided that the aim of Annex I Parties stabilizing their emissions at 1990 levels by 2000 was "not adequate", and further discussions at later conferences led to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The Kyoto Protocol was concluded and established legally binding obligations under international law, for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2008–2012. The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference produced an agreement stating that future global warming should be limited to below 2 °C (3.6 °F) relative to the pre-industrial level. The Kyoto Protocol had two commitment periods, the first of which lasted from 2008 to 2012. The Protocol was amended in 2012 to encompass the second one for the period 2013–2020 in the Doha Amendment.

One of the first tasks set by the UNFCCC was for signatory nations to establish national greenhouse gas inventories of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and removals, which were used to create the 1990 benchmark levels for accession of Annex I countries to the Kyoto Protocol and for the commitment of those countries to GHG reductions. Updated inventories must be submitted annually by Annex I countries.

The US did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol, while Canada denounced it in 2012. The Kyoto Protocol was ratified by all the other Annex I Parties.

All Annex I Parties, excluding the US, participated in the 1st Kyoto commitment period. Thirty-seven Annex I countries and the EU agreed to second-round Kyoto targets. These countries are Australia, all members of the European Union, Belarus, Iceland, Kazakhstan, Norway, Switzerland, and Ukraine. Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine stated that they might withdraw from the Protocol or not put into legal force the Amendment with second round targets. Japan, New Zealand, and Russia participated in Kyoto's first round but did not take on new targets in the second commitment period. Other developed countries without second-round targets were Canada (which withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2012) and the United States.

All countries that remained parties to the Kyoto Protocol met their first commitment period targets.

National communication

A "National Communication" is a type of report submitted by the countries that have ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Developed countries are required to submit National Communications every four years and developing countries should do so. Some Least Developed Countries have not submitted National Communications in the past 5–15 years, largely due to capacity constraints.

National Communication reports are often several hundred pages long and cover a country's measures to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions as well as a description of its vulnerabilities and impacts from climate change. National Communications are prepared according to guidelines that have been agreed by the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC. The (Intended) Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that form the basis of the Paris Agreement are shorter and less detailed but also follow a standardized structure and are subject to technical review by experts.

Paris Agreement

The parties met in Durban, South Africa in 2011 and expressed "grave concern" that efforts to limit global warming to less than 2 or 1.5 °C, relative to the pre-industrial level, appeared inadequate. They committed to develop an "agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties".

At the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris the then-196 parties agreed to aim to limit global warming to less than 2 °C, and try to limit the increase to 1.5 °C. The Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016 in those countries that had ratified the Agreement, and other countries had ratified the Agreement since.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

At the 19th session of the Conference of the Parties in Warsaw in 2013, the UNFCCC created a mechanism for Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) to be submitted in the run up to the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties in Paris (COP21) in 2015. Countries were given freedom and flexibility to ensure that these climate change mitigation and adaptation plans were nationally appropriate. This flexibility, especially regarding the types of actions to be undertaken, allowed for developing countries to tailor their plans to their specific adaptation and mitigation needs, as well as towards other needs.

In the aftermath of COP21, these INDCs became Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as each country ratified the Paris Agreement, unless a new NDC was submitted to the UNFCCC at the same time. The 22nd session of the Conference of the Parties (COP22) in Marrakesh focused on these Nationally Determined Contributions and their implementation, after the Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016.

The Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) created a guide for NDC implementation, for the use of decision makers in Less Developed Countries. In this guide, CDKN identified a series of common challenges countries face in NDC implementation, including how to:

- build awareness of the need for, and benefits of, action among stakeholders, including key government ministries;

- mainstream and integrate climate change into national planning and development processes;

- strengthen the links between subnational and national government plans on climate change;

- build capacity to analyse, develop and implement climate policy;

- establish a mandate for coordinating actions around NDCs and driving their implementation; and

- address resource constraints for developing and implementing climate change policy.

Further commitments

In addition to the Kyoto Protocol (and its amendment) and the Paris Agreement, parties to the Convention have agreed to further commitments during UNFCCC Conferences of the Parties. These include the Bali Action Plan (2007), the Copenhagen Accord (2009), the Cancún agreements (2010), and the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (2012).

- Bali Action Plan

As part of the Bali Action Plan, adopted in 2007, all developed country Parties have agreed to "quantified emission limitation and reduction objectives, while ensuring the comparability of efforts among them, taking into account differences in their national circumstances." Developing country Parties agreed to "[nationally] appropriate mitigation actions context of sustainable development, supported and enabled by technology, financing and capacity-building, in a measurable, reportable and verifiable manner." 42 developed countries have submitted mitigation targets to the UNFCCC secretariat, as have 57 developing countries and the African Group (a group of countries within the UN).

- Copenhagen Accord and Cancún agreements

As part of the 2009 Copenhagen negotiations, a number of countries produced the Copenhagen Accord. The Accord states that global warming should be limited to below 2.0 °C (3.6 °F). The Accord does not specify what the baseline is for these temperature targets (e.g., relative to pre-industrial or 1990 temperatures). According to the UNFCCC, these targets are relative to pre-industrial temperatures.

114 countries agreed to the Accord. The UNFCCC secretariat notes that "Some Parties ... stated in their communications to the secretariat specific understandings on the nature of the Accord and related matters, based on which they have agreed to [the Accord]." The Accord was not formally adopted by the Conference of the Parties. Instead, the COP "took note of the Copenhagen Accord."

As part of the Accord, 17 developed country Parties and the EU-27 submitted mitigation targets, as did 45 developing country Parties. Some developing country Parties noted the need for international support in their plans.

As part of the Cancún agreements, developed and developing countries submitted mitigation plans to the UNFCCC. These plans were compiled with those made as part of the Bali Action Plan.

- UN Race-to-Zero Emissions Breakthroughs

At the 2021 annual meeting UNFCCC launched the 'UN Race-to-Zero Emissions Breakthroughs'. The aim of the campaign is to transform 20 sectors of the economy in order to achieve zero greenhouse gas emissions. At least 20% of each sector should take specific measures, and 10 sectors should be transformed before COP 26 in Glasgow. According to the organizers, 20% is a tipping point, after which the whole sector begins to irreversibly change.

- Developing countries

At Berlin, Cancún, and Durban, the development needs of developing country parties were reiterated. For example, the Durban Platform reaffirms that:

[...] social and economic development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of developing country Parties, and that a low-emission development strategy is central to sustainable development, and that the share of global emissions originating in developing countries will grow to meet their social and development needs.

Parties

As of 2022, the UNFCCC has 198 parties including all United Nations member states, United Nations General Assembly observers the State of Palestine and the Holy See, UN non-member states Niue and the Cook Islands, and the supranational union European Union.

Classification of Parties and their commitments

Parties to the UNFCCC are classified as:

- Annex I: There are 43 Parties to the UNFCCC listed in Annex I of the convention, including the European Union. These Parties are classified as industrialized (developed) countries and "economies in transition" (EITs). The 14 EITs are the former centrally-planned (Soviet) economies of Russia and Eastern Europe.

- Annex II: Of the Parties listed in Annex I of the convention, 24 are also listed in Annex II of the convention, including the European Union. These Parties are made up of members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): these Parties consist of the members of the OECD in 1992, minus Turkey, plus the EU. Annex II Parties are required to provide financial and technical support to the EITs and developing countries to assist them in reducing their greenhouse gas emissions (climate change mitigation) and manage the impacts of climate change (climate change adaptation).

- Least-developed countries (LDCs): 49 Parties are LDCs, and are given special status under the treaty in view of their limited capacity to adapt to the effects of climate change.

- Non-Annex I: Parties to the UNFCCC not listed in Annex I of the convention are mostly low-income developing countries. Developing countries may volunteer to become Annex I countries when they are sufficiently developed.

List of parties

Annex I countries

There are 43 Annex I Parties including the European Union. These countries are classified as industrialized countries and economies in transition. Of these, 24 are Annex II Parties, including the European Union, and 14 are Economies in Transition.

Australia

Australia Austria

Austria Belarus

Belarus Belgium

Belgium Bulgaria

Bulgaria Canada

Canada Croatia

Croatia Cyprus

Cyprus Czech Republic

Czech Republic Denmark

Denmark Estonia

Estonia EU

EU Finland

Finland France

France Germany

Germany Greece

Greece Hungary

Hungary Iceland

Iceland Ireland

Ireland Italy

Italy Japan

Japan Latvia

Latvia Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein Lithuania

Lithuania Luxembourg

Luxembourg Malta

Malta Monaco

Monaco Netherlands

Netherlands New Zealand

New Zealand Norway

Norway Poland

Poland Portugal

Portugal Romania

Romania Russian Federation

Russian Federation Slovakia

Slovakia Slovenia

Slovenia Spain

Spain Sweden

Sweden Switzerland

Switzerland Turkey

Turkey Ukraine

Ukraine United Kingdom

United Kingdom United States of America

United States of America

- Notes

- Economy in Transition

Conferences of the Parties (CoP)

The United Nations Climate Change Conference are yearly conferences held in the framework of the UNFCCC. They serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC Parties (Conferences of the Parties) (COP) to assess progress in dealing with climate change, and beginning in the mid-1990s, to negotiate the Kyoto Protocol to establish legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Since 2005 the Conferences also served as the Meetings of Parties of the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) and since 2016 the Conferences also serve as Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA).

The first conference (COP1) was held in 1995 in Berlin. The 3rd conference (COP3) was held in Kyoto and resulted in the Kyoto protocol, which was amended during the 2012 Doha Conference (COP18, CMP 8). The COP21 (CMP11) conference was held in Paris and resulted in adoption of the Paris Agreement. The COP26 (CMA3) was held in Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom. COP28 is taking place at the United Arab Emirates and Sultan al-Jaber has been nominated by the ruler to lead the same.

Subsidiary bodies

A subsidiary body is a committee that assists the Conference of the Parties. Subsidiary bodies include:

- Permanents:

- The Subsidiary Body of Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) is established by Article 9 of the convention to provide the Conference of the Parties and, as appropriate, its other subsidiary bodies with timely information and advice on scientific and technological matters relating to the convention. It serves as a link between information and assessments provided by expert sources (such as the IPCC) and the COP, which focuses on setting policy.

- The Subsidiary Body of Implementation (SBI) is established by Article 10 of the convention to assist the Conference of the Parties in the assessment and review of the effective implementation of the convention. It makes recommendations on policy and implementation issues to the COP and, if requested, to other bodies.

- Temporary:

- Ad hoc Group on Article 13 (AG13), active from 1995 to 1998;

- Ad hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate (AGBM), active from 1995 to 1997;

- Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP), established in 2005 by the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol to consider further commitments of industrialized countries under the Kyoto Protocol for the period beyond 2012; it concluded its work in 2012 when the CMP adopted the Doha Amendment;

- Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action (AWG-LCA), established in Bali in 2007 to conduct negotiations on a strengthened international deal on climate change;

- Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP), established at COP 17 in Durban in 2011 "to develop a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties." The ADP concluded its work in Paris on 5 December 2015.

Secretariat

The work under the UNFCCC is facilitated by a secretariat in Bonn, Germany. The secretariat is established under Article 8 of the convention and headed by the Executive Secretary. Patricia Espinosa was appointed Executive Secretary on 18 May 2016 by United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and took office on 18 July 2016. Espinosa retired on 16 July 2022. UN Under Secretary General Ibrahim Thiaw acts as the acting Executive Secretary in the interim. On 15 August 2022, Secretary-General António Guterres appointed former Grenadian climate minister Simon Stiell as Executive Secretary, replacing Espinosa.

Commentaries and analysis

Interpreting article 2

The ultimate objective of the Framework Convention is "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic [i.e., human-caused] interference with the climate system". Article 2 of the convention says this "should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner".

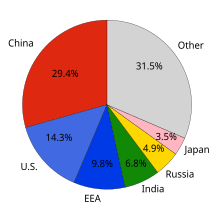

To stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations, global anthropogenic GHG emissions would need to peak then decline (see climate change mitigation). Lower stabilization levels would require emissions to peak and decline earlier compared to higher stabilization levels. The graph above shows projected changes in annual global GHG emissions (measured in CO2-equivalents) for various stabilization scenarios. The other two graphs show the associated changes in atmospheric GHG concentrations (in CO2-equivalents) and global mean temperature for these scenarios. Lower stabilization levels are associated with lower magnitudes of global warming compared to higher stabilization levels.

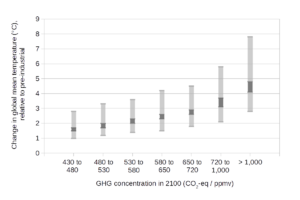

There is uncertainty over how GHG concentrations and global temperatures will change in response to anthropogenic emissions (see climate change feedback and climate sensitivity). The graph opposite shows global temperature changes in the year 2100 for a range of emission scenarios, including uncertainty estimates.

- Dangerous anthropogenic interference

There are a range of views over what level of climate change is dangerous. Scientific analysis can provide information on the risks of climate change, but deciding which risks are dangerous requires value judgements.

The global warming that has already occurred poses a risk to some human and natural systems (e.g., coral reefs). Higher magnitudes of global warming will generally increase the risk of negative impacts. According to Field et al. (2014), climate change risks are "considerable" with 1 to 2 °C of global warming, relative to pre-industrial levels. 4 °C warming would lead to significantly increased risks, with potential impacts including widespread loss of biodiversity and reduced global and regional food security.

Climate change policies may lead to costs that are relevant to the article 2. For example, more stringent policies to control GHG emissions may reduce the risk of more severe climate change, but may also be more expensive to implement.

- Projections

There is considerable uncertainty over future changes in anthropogenic GHG emissions, atmospheric GHG concentrations, and associated climate change. Without mitigation policies, increased energy demand and extensive use of fossil fuels could lead to global warming (in 2100) of 3.7 to 4.8 °C relative to pre-industrial levels (2.5 to 7.8 °C including climate uncertainty).

To have a likely chance of limiting global warming (in 2100) to below 2 °C, GHG concentrations would need to be limited to around 450 ppm CO2-eq. The current trajectory of global emissions does not appear to be consistent with limiting global warming to below 1.5 or 2 °C.

Precautionary principle

In decision making, the precautionary principle is considered when possibly dangerous, irreversible, or catastrophic events are identified, but scientific evaluation of the potential damage is not sufficiently certain (Toth et al., 2001, pp. 655–656). The precautionary principle implies an emphasis on the need to prevent such adverse effects.

Uncertainty is associated with each link of the causal chain of climate change. For example, future GHG emissions are uncertain, as are climate change damages. However, following the precautionary principle, uncertainty is not a reason for inaction, and this is acknowledged in Article 3.3 of the UNFCCC (Toth et al., 2001, p. 656).

Criticisms of the UNFCCC process

The overall umbrella and processes of the UNFCCC and the adopted Kyoto Protocol have been criticized by some as not having achieved their stated goals of reducing the emission of carbon dioxide (the primary driver of rising global temperatures of the 21st century). At a speech given at his alma mater, Todd Stern—the US Climate Change envoy—expressed the challenges with the UNFCCC process as follows: "Climate change is not a conventional environmental issue ... It implicates virtually every aspect of a state's economy, so it makes countries nervous about growth and development. This is an economic issue every bit as it is an environmental one." He went on to explain that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is a multilateral body concerned with climate change and can be an inefficient system for enacting international policy. Because the framework system includes over 190 countries and because negotiations are governed by consensus, small groups of countries can often block progress.

The failure to achieve meaningful progress and reach effective CO2-reducing policy treaties among the parties over the past eighteen years has driven some countries like the United States to hold back from ratifying the UNFCCC's most important agreement—the Kyoto Protocol—in large part because the treaty did not cover developing countries which now include the largest CO2 emitters. However, this failed to take into account both the historical responsibility for climate change since industrialisation, which is a contentious issue in the talks, and also responsibility for emissions from consumption and importation of goods. It has also led Canada to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol in 2011 out of a wish not to make its citizens pay penalties that would result in wealth transfers out of Canada. Both the US and Canada are looking at internal Voluntary Emissions Reduction schemes to curb carbon dioxide emissions outside the Kyoto Protocol.

The perceived lack of progress has also led some countries to seek and focus on alternative high-value activities like the creation of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants which seeks to regulate short-lived pollutants such as methane, black carbon and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which together are believed to account for up to 1/3 of current global warming but whose regulation is not as fraught with wide economic impacts and opposition.

In 2010, Japan stated that it will not sign up to a second Kyoto term, because it would impose restrictions on it not faced by its main economic competitors, China, India and Indonesia. A similar indication was given by the Prime Minister of New Zealand in November 2012. At the 2012 conference, last-minute objections at the conference by Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan were ignored by the governing officials, and they have indicated that they will likely withdraw or not ratify the treaty. These defections place additional pressures on the UNFCCC process that is seen by some as cumbersome and expensive: in the UK alone, the climate change department has taken over 3,000 flights in two years at a cost of over £1,300,000 (British pounds sterling).

Further, the UNFCCC (mainly during the Kyoto protocol) failed to facilitate the transfer of environmentally sound technologies (SETs) which are mechanisms used to decrease the vulnerability of the human race against the unfavourable effects of climate change. One of the more widely used of these being renewable energy sources. The UNFCCC created the body "technology mechanism" who would distribute these resources to developing countries; however this distribution was too moderate and, coupled with the failings of the first commitment period of the Kyoto protocol, led to low ratification numbers for the second commitment (resulting in it not going ahead).

Before the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, National Geographic magazine added to the criticism, writing: "Since 1992, when the world's nations agreed at Rio de Janeiro to avoid 'dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system,' they've met 20 times without moving the needle on carbon emissions. In that interval we've added almost as much carbon to the atmosphere as we did in the previous century."

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is the setting of a policy target based on some frame of reference. An example of benchmarking is the UNFCCC's original target of Annex I Parties limiting their greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2000. Goldemberg et al. (1996) commented on the economic implications of this target. Although the target applies equally to all Annex I Parties, the economic costs of meeting the target would likely vary between Parties. For example, countries with initially high levels of energy efficiency might find it more costly to meet the target than countries with lower levels of energy efficiency. From this perspective, the UNFCCC target could be viewed as inequitable, i.e., unfair.

Benchmarking has also been discussed in relation to the first-round emissions targets specified in the Kyoto Protocol (see views on the Kyoto Protocol and Kyoto Protocol and government action).

International trade

Academics and environmentalists criticize article 3(5) of the convention, which states that any climate measures that would restrict international trade should be avoided.

Engagement of civil society

In 2014, The UN with Peru and France created the Global Climate Action Portal NAZCA for writing and checking all the climate commitments.

Civil Society Observers under the UNFCCC have organized themselves in loose groups, covering about 90% of all admitted organisations. Some groups remain outside these broad groupings, such as faith groups or national parliamentarians.

An overview is given in the table below:

| Name | Abbreviation | Admitted since |

|---|---|---|

| Business and industry NGOs | BINGO | 1992 |

| Environmental NGOs | ENGO | 1992 |

| Local government and municipal authorities | LGMA | COP1 (1995) |

| Indigenous peoples organizations | IPO | COP7 (2001) |

| Research and independent NGOs | RINGO | COP9 (2003) |

| Trade union NGOs | TUNGO | Before COP 14 (2008) |

| Women and gender | WGC | Shortly before COP17 (2011) |

| Youth NGOs | YOUNGO Archived 19 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine | Shortly before COP17 (2011) |

| Farmers | Farmers | (2014) |

UNFCCC secretariat also recognizes the following groups as informal NGO groups (2016):

| Name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Faith Based Organizations | FBOs |

| Education and Capacity Building and Outreach NGOs | ECONG |

| Parliamentarians |